During the colonial period, despite scarce knowledge and resources, doctors and apothecaries developed medical prescriptions mainly of vegetable origin for the management of multiple diseases, including gout.

ObjectiveTo contextualise and describe the use of medical prescription in the early 19th century in the New Kingdom of Granada for the treatment of gout.

Material and methodsA documentary search of medical prescription was carried out in the Cipriano Rodríguez Santamaría Historical Archive of the Octavio Arizmendi Posada Library of the University of La Sabana. Subsequently, an open literature review was carried out in the ScienceDirect, ClinicalKey, and Scielo databases in English and Spanish.

ResultsPistacia lentiscus, the basis of the recipe described, has a high content of terpenes, tannins, flavonoids, and coumarins, which generate anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antibiotic, antiviral, and anti-atherogenic effects, among others.

ConclusionMastic, one of the components of these recipes, possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, which could explain its relative efficacy in the treatment of gout in the 19th century.

Durante el periodo colonial, pese a los escasos conocimientos y recursos, médicos y boticarios desarrollaron recetas médicas principalmente de origen vegetal para el manejo de múltiples enfermedades, incluyendo la gota.

ObjetivoContextualizar y describir el uso de una receta médica a comienzos del siglo XIX en el Nuevo Reino de Granada como tratamiento de la gota.

Materiales y métodosSe llevó a cabo una búsqueda documental de la receta médica en el Archivo Histórico Cipriano Rodríguez Santamaría de la Biblioteca Octavio Arizmendi Posada de la Universidad de La Sabana, Chía (Colombia). Posteriormente, se realizó una revisión de la literatura sin límite de tiempo, en las bases de datos ScienceDirect, ClinicalKey y Scielo, en inglés y español.

ResultadosPistacia lentiscus, base de la receta descrita, tiene un alto contenido de terpenos, taninos, flavonoides y cumarinas, lo que genera efectos antiinflamatorios, antimicrobianos, antioxidantes, antibióticos, antivirales y antiaterogénicos, entre otros.

ConclusiónEl lentisco, uno de los componentes de estas recetas, posee propiedades antiinflamatorias y antioxidantes que podrían explicar su relativa eficacia en el tratamiento de la gota en el siglo XIX.

Gouty arthritis has been studied since ancient times. The first to describe it were the Greek and Byzantine physicians, approximately in the year 2640 B.C.1,2 Later, Hippocrates of Kos (480–397 B.C.) described gout as a non-communicable disease that affects men and results from a disordered life.3 At that time it was also believed that this disease was the result of a poison in the joints.4 After that, Claudius Galenus (2nd century AD) introduced a powerful purgative based on Colchicum autumnale for its treatment.5

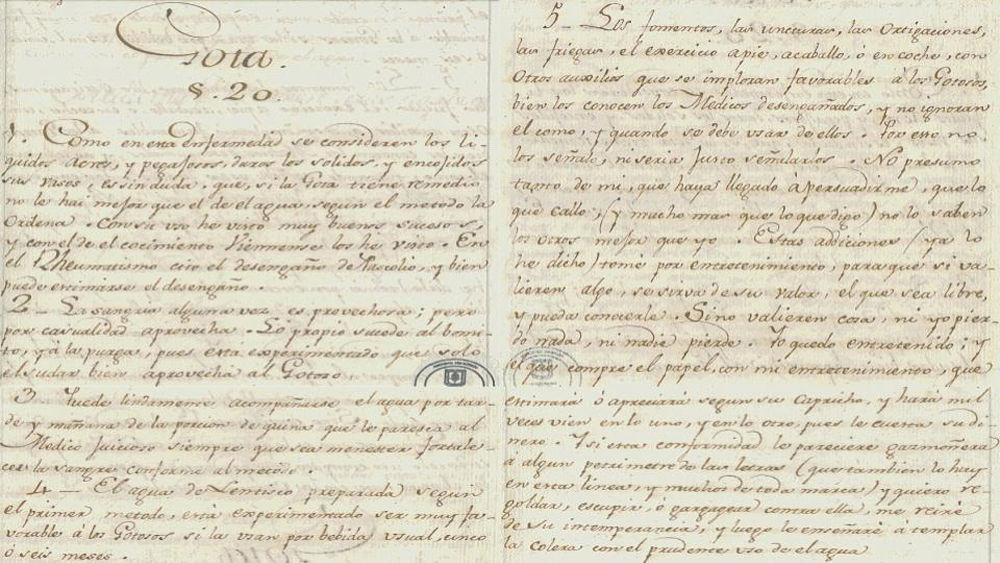

The Historical Archive of the Octavio Arizmendi Posada Library of the University of La Sabana (Chía, Colombia), preserves medical prescriptions written in the 18th and 19th Centuries in the New Kingdom of Granada, which were donated to the University by Father Cipriano Rodríguez Santa María, institutional eponym of the archive (AHCRS). A recipe prescribed for the management of manifestations associated to the gout illness is analyzed in this article (Fig. 1). Simultaneously, its sociocultural and medical legacy is evaluated in terms of the use of its phytotherapeutic agents in the New Kingdom of Granada.

Material and methodsA documentary search was carried out in the Historical Archive of the Octavio Arizmendi Posada Library, at the University of La Sabana, as a result of which the recipe "Gout" was found. Simultaneously, a historical tour around the evolution of the treatment of rheumatism was made, as well as a compilation of the available bibliographic references on the components or phytotherapeutic substances of the recipe under study. For this purpose, databases such as Scopus, PubMed, SciELO and Google Scholar were used, without time limit, and with the following search terms: “rheumatic diseases”, “history”, “pain”, “Pistacia lentiscus”.

ResultsBeginning of gout in Greek medicinePodagra (from the Greek podos, “foot”, and agreos, “to grasp” “to attack”) was described by the Egyptians as a probable acute attack of gout in the first metatarsophalangeal joint or the big toe of the foot.2 Hippocrates of Kos specified that this was not a communicable disease and that it mainly affected the wealthy population, due to a lifestyle characterized by a high consumption of foods such as red meats and wine in excess,6 and in his aphorisms he specified characteristics features of gout.3 Despite this, many aspects related to this condition were still unknown some time later, although some efforts to increase knowledge in this respect are highlighted. For example, Celsus (25 B.C.–50 A.D.) still did not know the differences between rheumatism and gout7,8; Claudius Galenus supported the association between high alcohol consumption and gout mentioned by Hippocrates,7 and later Lucius Annaeus Seneca and Aretaeus of Cappadocia described a hereditary component, which was gradually lost over time due to the lack of formalization of knowledge on this subject.9

Definition of gout based on podagraByzantine physicians believed that an excess of humors was the direct cause of podagra. Randolph Bocking was a prominent English Dominican monk of the 13th century and the first to use the word gout to describe podagra.7,9 Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689), defender of Hippocratic medicine and who suffered from gout, recorded the most extensive descriptions of the clinical manifestations in his Treatise on gout and dropsies, and mentioned the risk factors, crises and chronic gout.7,10

Disease of nobility and kingsSince the first definitions and studies, gout was associated with opulent people, such as politicians, popes or kings, who had the economic capacity to maintain a sedentary lifestyle and with excesses.4,10 A clear example is presented in the Medici family, formed by great aristocrats, elite of Florence (Italy). Multiple painful episodes in the hands, feet and spine were reported in several members of the family, hence the renowned term of the gout of the Medici.11 Studies of historical pathology provided evidence that linked a lifestyle full of excesses in wines and red meats with the existence of gout in 2 out of 9 adult men in this family.12,13

The illustration by the hand of Mutis in the New GranadaIn colonial times in America, the independence movements had their greatest effervescence thanks to the Illustration, a process initiated in the New Kingdom of Granada, consciously or unconsciously, by precursors such as José Celestino Mutis (1732–1808) and his disciples of the Royal Botanical Expedition.14,15 These illustrated people promoted an education movement through reason that should be taught to all social classes in search of literacy for the greatest number of inhabitants.16 The Illustration brought with it several research projects, one of them was the Botanical Expedition, considered “the largest Spanish scientific enterprise of the colonial era.” It explored all types of fauna, flora and gea of the territory of the Viceroyalty of New Granada between the years 1783 and 1816, and its results were consolidated in the 35 volumes of the Flora of the Royal Botanical Expedition of the New Kingdom of Granada. This program, naturally, promoted the medicinal use of native plants from the New World.15,17

Doctors and apothecaries, pillars of health in the ViceroyaltyThe trades related to health or medicine in the period of Hispanic rule were exercised by doctors, surgeons, barbers and apothecaries. Doctors were in charge of prescribing medical remedies after examining the patient. After that, the patient went to a medical pharmacy in which the apothecary distributed the medicine, whose components had been previously cultured and processed by this apothecary, who could not prescribe without medical prescription, as well as the doctors who could not produce or dispense the prescriptions.18 Despite this, sometimes the proper diagnosis and definitive treatment of the different human pathologies were affected by the absence of a specific method and medications that relieved the disease and not just the symptom.19

Gout in the New Kingdom of GranadaThe medical prescriptions used in the New Kingdom of Granada were of vegetable, animal or mineral origin, and were consequently classified by their physicochemical characteristics.20 Rheumatoid arthritis and gout are probably the musculoskeletal disorders that most affected the inhabitants of New Granada at that time, although the lack of data and definitions of these pathologies makes it difficult to specify exactly the degree of suffering of the patients. Below is the transcript of the source document in which the symptomatic management of the patient with gout is presented and the characteristics of the main components of the prescription are described, as well as the symptoms that affected the patients:

- 1.

As in this disease the liquids are considered acrid and sticky, the solids hard, and their vessels shrunken, it is undoubtedly that, if Gout has a remedy, there is no better remedy than water, according to what is Ordered by the method. With its use I have seen very good events, and with the Viennese cooking I have seen them. In Rheumatism I quote Pascolio’s disappointment and the disappointment can well be estimated.

- 2.

Bloodletting is sometimes beneficial; but by chance it is helpful. The same thing happens to vomiting, and to purging, since it is experienced that only sweating is good for the Gouty.

- 3.

The water can be nicely accompanied in the evening and morning with the portion of cinchona that the judicious Doctor finds adequate whenever it is necessary to strengthen the blood according to the method.

- 4.

Mastic water prepared according to the first method is proven to be very favorable to Gouty people if they use it as a regular drink for five or six months.

- 5.

The fomentations, the ointments, the oxtigations, the scrubs, the exercise on foot, on horseback, or in a car, with other aids that are implored favorable to the Gouty, are well known by the disappointed Doctors, and they do not ignore the how, and the when they should be used. That's why I don't point them out, nor would it be Fair to point them out. I do not presume so much about myself that I have managed to persuade myself that what I keep silent about (and much more than what I say) others do not know any better than I do. I took these additions (I have already said it) for entertainment, so that if they were worth anything, they would use their value, which is free, and can know them. If they are worthless, neither I lose anything, nor does anyone lose. I am entertained; and whoever buys the paper, with my entertainment, which will estimate or appreciate it according to his whim, and will do a thousand times good in one and the other, since it costs him his money. And if this conformity seems prudish to some literary nerd (which there is also in this line, and many of all brands) and I want to snarl, spit, or gargle at her, I will laugh at her intemperance, and then I will teach her to temper anger with the prudent use of water.

Pistacia, a genus belonging to the Anacardiaceae family, a family with about 600 distinct native species from Mediterranean Europe and North Africa, has been widely used for more than 5000 years: in traditional Greek medicine, as a chiclet or chewing gum for the treatment of gastrointestinal symptoms such as epigastralgia; as a sweetener for wheat derivatives in ancient Egypt, and today, in modern medicine, for its wide catalog of beneficial effects for human beings.

The most studied species is mastic, or Pistacia lentiscus, in particular its resin, due to its effects attributable to terpenes, tannins, flavonoids and coumarins, among others.21 These phytotherapeutic substances have anti-inflammatory effects that inhibit the expression of TNF-a, IL-6 and NF-κB, as well as the production of superoxide or H2O2 by NADPH oxidase.22–25 It has been demonstrated decreased intracellular mutagenic activity, inhibition of chemokine expression and neovascularization of tumor lesions in different histological types.26–28Pistacia displays extensive antimicrobial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, including Streptococcus mutans and Escherichia coli.29,30 Finally, its antioxidant, antibiotic, antiviral, antiatherogenic, hypoglycemic, hepatoprotective and nephroprotective effects that characterize it should be mentioned.21,31–34

Xanthine oxidase (XO) is an enzyme that is widely distributed in the tissues, responsible for the degradation of purines and the generation in pathological conditions of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and uric acid in excess; it is related to a high number of inflammatory diseases such as gout, rheumatoid arthritis, acute myocardial infarction and hypertension.34 Recent studies demonstrate notable XO inhibitory activity by Pistacia lentiscus leaf extracts due to their high content of phenols, tannins and flavonoids. Currently, XO-inhibitors are used in the treatment of gout; Pistacia lentiscus extracts can be related to positive phytotherapeutic effects on the disease.35–37 On the other hand, their high capacity to capture free radicals and protection against lipid peroxidation are known.38

Gout arthritis: a current definition with a great legacyGout is an arthritis caused by deposits of monosodium urate crystals in the joints and adjacent tissues, consistent with persistent hiperuricemia.39 It manifests itself mainly in adult male population and affects the metatarsophalangeal joint of the first toe, among others. The etiopathogenesis of the disease is attributed to risk factors that decrease excretion and increase production of uric acid, with lifestyle being the most relevant.40 Impacting risk factors and modifying lifestyle, such as alcohol intake, is essential in its medical treatment. Currently, the pharmacological treatment of gout in its different stages (acute, chronic or intercritical) includes non-specific drugs such as colchicine, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids and specific drugs of the uric acid metabolic pathway, such as XO inhibitors, recombinant urate oxidase enzymes and uricosuric medications.39,40

ConclusionMastik, the main compound of the Neogranadine medication described in this article, has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and XO enzyme inhibitory properties, which might have a benevolent effect and have improved the ailments of the patients in the 19th century. On the contrary, the habit of prescribing alcohol in the recipe can be counterproductive, because it is a factor that produces purines which negatively affect this pathology, as we currently know. Despite a vague description of the administration of the drug, the clinical manifestations of the disease and the total absence of clinical evolution of patients that make difficult the analysis of the medical prescription, it should be noted the valuable work of doctors and apothecaries from New Granada, who, with little knowledge, managed to develop a relatively useful drug in the primary management of gout.

FundingThe process of research and publication was funded by the universities to which the authors are affiliated.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest for the preparation of this article.