Haemophilic arthropathy presents with different important clinical disorders, such as joint disease, pain, decreased range of motion, and functional alterations that can produce limitations in functionality and mobility. The physical exercise adapted to patients with haemophilia can be an adequate therapeutic strategy, having a positive impact on the quality of life of these subjects.

ObjectivesTo identify the published clinical trials that evaluate the efficacy of physical rehabilitation in the treatment of haemophilic arthropathy.

Materials and methodsA systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials was conducted (using pre-defined eligibility criteria). The literature search was performed in the databases: PEDro, Pubmed, Scopus, and Web of Science. The quality of the methods used in the studies was evaluated using the PEDro scale.

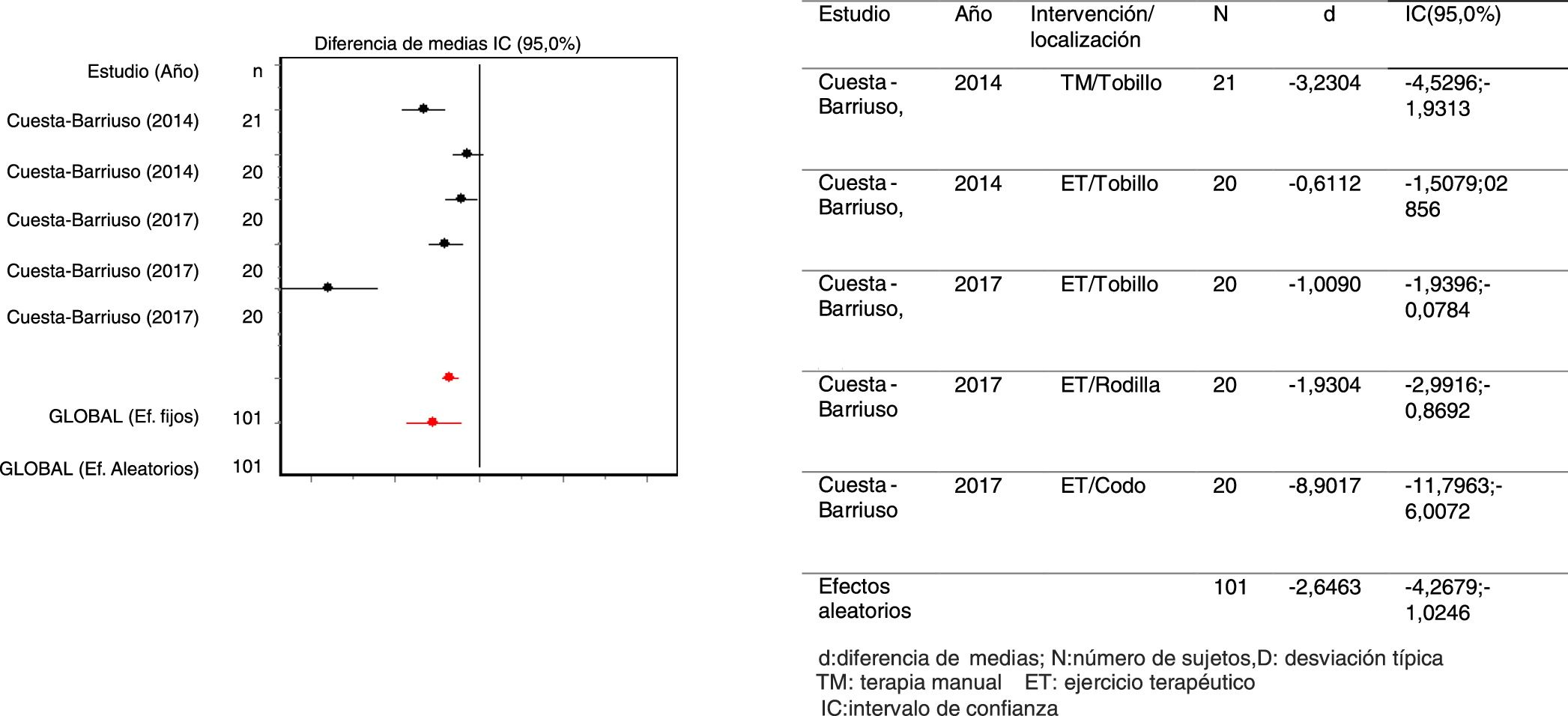

ResultsAfter applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 7 studies were included in this review, providing favourable results on muscle strength and circumference, range of motion, joint disease, and quality of life. Moreover, 2 articles contributed information to the meta-analysis, showing favourable results on pain [Standardised mean difference (SMD) = −2.64; 95% CI: (−4.26 − +1.03)].

ConclusionsThis systematic review found evidence on the efficacy of physical rehabilitation in the treatment for haemophilic arthropathy. Therapeutic exercise is the main treatment carried out, obtaining significant improvements in the different physical outcomes.

La artropatía hemofílica cursa con diferentes manifestaciones clínicas importantes, como son las hemorragias articulares, dolor, disminución de la amplitud de movimiento y alteraciones funcionales que pueden causar secuelas a nivel de funcionalidad y movilidad. El ejercicio físico adaptado a los pacientes con hemofilia puede ser una adecuada estrategia terapéutica, repercutiendo positivamente sobre la calidad de vida de dichos sujetos.

ObjetivosEvaluar la eficacia de la rehabilitación física en el tratamiento de la artropatía hemofílica. Materiales y métodos: Se ha realizado una revisión sistemática y meta-análisis de ensayos clínicos (seleccionados según criterios de elegibilidad). Para ello, se han utilizado las siguientes bases de datos: PEDro, Pubmed, Scopus y Web of Science. Se empleó la escala “PEDro” para evaluar la calidad metodológica de los estudios.

ResultadosTras aplicar los criterios de inclusión y exclusión, 7 artículos fueron incluidos en la revisión final, aportando resultados favorables sobre la fuerza y diámetro muscular, rango de movilidad y estado articular, y calidad de vida. De ellos, 2 estudios aportaron datos para meta-análisis, mostrando resultados favorables sobre la variable: dolor [Diferencia de medias estandarizada (DME)=-2,64; IC95%:(-4,26;1,03)].

ConclusionesSe encontró evidencia sobre la eficacia de la rehabilitación física en el tratamiento de la artropatía hemofílica. El ejercicio terapéutico es el principal tratamiento realizado, obteniendo mejoras significativas en distintas variables físicas.

Hemophilia is a congenital, hemorrhagic, recessive disease; hemophilia A and B are inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern.1 However, there is a third type of hemophilia, Type C, which not chromosome X-linked. This condition causes a clotting deficiency due to the absence or deficiency of one of the coagulation factors2: factor VIII for type A, factor IX for type B, and factor XI for type C.

Currently, hemophilia is considered a rare disease because of its low prevalence.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Federation of Hemophilia (WFH) estimate the prevalence of hemophilia A at around one per every 5000 births, whilst hemophilia B has a prevalence of one per every 30,000 births, for an overall prevalence of approximately one in every 7500 births. The disease affects all races and socioeconomic groups equally.4

The most important clinical manifestations of hemophilia are hemorrhages,5 which cause pain, reduce the range of movement (ROM) and lead to functional alterations that may result in disability.6 Of those hemorrhages, 80% are articular,6 with major functional and mobility sequelae.7 The most affected joints are: the ankle (33%), usually experiencing more bleeding episodes during early childhood and commonly presenting arthropathy during adolescence,8 the knee (33%), and the elbow, shoulder, and hip (33%).9

Hemophilic arthropathy (HA) develops as a result of the natural evolution of joint damage and affects a large number of individuals,10 leading to a process of joint degeneration.11 Clinically, HA presents with hemarthrosis, which causes muscular atrophy, joint instability and even synovitis, which in turn results in more frequent and severe bleeding.12 Around 66% of the patients with HA do not receive proper rehabilitation11; therefore, there is need to create awareness about the benefits derived from rehabilitation in these patients, in order to encourage further development of these services.

After looking into the scientific literature available, there are no meta-analyses gathering the principal trials on HA rehabilitation; the variability of the interventions and the variables measured make the task difficult. However, there are some reviews emphasizing the benefits of physical activity to solve the problems derived from HA. All the studies say that physical exercise adapted to patients with hemophilia may be an adequate therapeutic strategy with a significant impact on quality of life.2,11,13,14 No systematic reviews have been identified either, compiling the current scientific evidence on the interventions based on other rehabilitation modalities, such as manual therapy (MT), stretching or electrostimulation.

Therefore, the primary objective of this systematic review is to identify and assess the efficacy of available therapies for patients with HA. The intent is to assess the different protocols used to improve this pathology, as well as any potential side effects that these therapies may have on patients.

MethodsThis study is based on a systematic review and meta-analysis pursuant to the Prisma guidelines.15

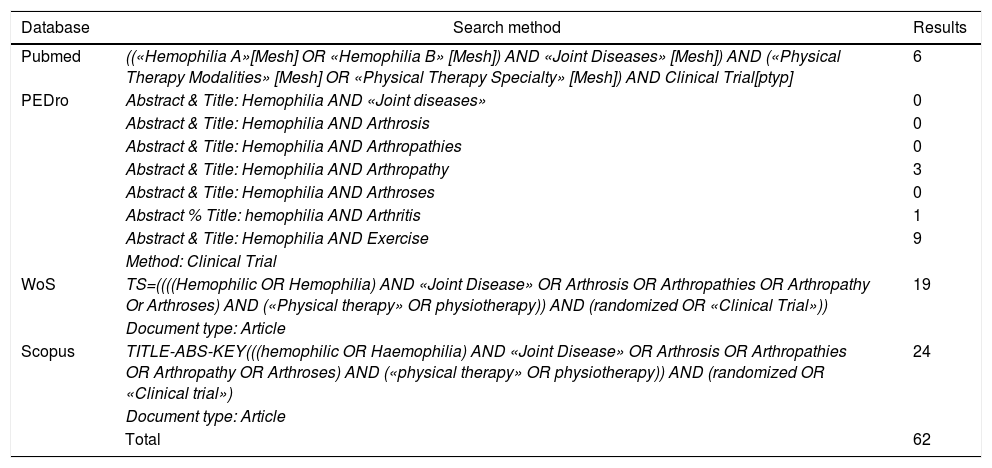

Search strategyA systematic literature review was conducted searching the following databases: PEDro, Pubmed, Scopus and Web of Science. The search was conducted until March 2017, using the following combination of search terms: «Hemophilia», «Joint Diseases» and «Physical Therapy» (Table 1). The search was limited to publications in English and Spanish, and there were no restrictions in terms of the date of publication.

Search equations.

| Database | Search method | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | ((«Hemophilia A»[Mesh] OR «Hemophilia B» [Mesh]) AND «Joint Diseases» [Mesh]) AND («Physical Therapy Modalities» [Mesh] OR «Physical Therapy Specialty» [Mesh]) AND Clinical Trial[ptyp] | 6 |

| PEDro | Abstract & Title: Hemophilia AND «Joint diseases» | 0 |

| Abstract & Title: Hemophilia AND Arthrosis | 0 | |

| Abstract & Title: Hemophilia AND Arthropathies | 0 | |

| Abstract & Title: Hemophilia AND Arthropathy | 3 | |

| Abstract & Title: Hemophilia AND Arthroses | 0 | |

| Abstract % Title: hemophilia AND Arthritis | 1 | |

| Abstract & Title: Hemophilia AND Exercise | 9 | |

| Method: Clinical Trial | ||

| WoS | TS=((((Hemophilic OR Hemophilia) AND «Joint Disease» OR Arthrosis OR Arthropathies OR Arthropathy Or Arthroses) AND («Physical therapy» OR physiotherapy)) AND (randomized OR «Clinical Trial»)) | 19 |

| Document type: Article | ||

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(((hemophilic OR Haemophilia) AND «Joint Disease» OR Arthrosis OR Arthropathies OR Arthropathy OR Arthroses) AND («physical therapy» OR physiotherapy)) AND (randomized OR «Clinical trial») | 24 |

| Document type: Article | ||

| Total | 62 |

The inclusion criteria used in this review were as follows: I) type of study = clinical trials (CT) and pilot studies; II) subjects = subjects of any age, diagnosed with HA; III) type of intervention: any potential physical therapy interventions,16 such as: therapeutic exercise, manual therapy, inter alia; IV) type of variable to be measured: physical variables included in the measurements of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)17; in sum, variables associated with body function, activities and participation; V) quality of the study = PEDro scale ≥5. Any duplicate trials found in various databases were eliminated. Finally, two reviewers independently analyzed the titles and the abstracts of each of the articles that met the above-mentioned criteria, and the full texts of each article were collected. This was the approach to collect the articles comprised in this review.

Assessment of the methodological qualityThe articles selected were assessed for quality, using a specific scale for the methodological assessment of CTs: the PEDro scale.18

This PEDro scale comprises 11 items, each of which is rated as present or absent, and contributes with one point to the total score (range = 0–10 points) assessing the methodological quality of the randomized clinical trials and classifies them in the PEDro database, which assists in informed clinical decision-making. This scale emphasizes two aspects of the trial: its internal validity and whether it contains enough statistical information for its interpretation.

According to Moseley et al.,19 the trials with a score ≥5 in this scale are rated as high methodological quality and low risk of bias. The score obtained using the PEDro scale in the analysis of the different trials included in this review is 9 for the highest value and 5 for the lowest.

Data miningTwo reviewers did the review independently and systematically extracted the data from each document; any discrepancies were solved by consensus. The following information was collected from each one of the articles reviewed: author, year of publication, characteristics of the participants, (number, mean age, type of hemophilia), characteristics of the intervention administered (type, duration, frequency), assessment conducted (times of the assessment, assessment instrument, variable to be measured), and finally, the results obtained.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was done using the specific EPIDAT 3.1 software from the General Directory of Public Health of Galicia, Spain. The heterogeneity tests were determined using the Dersimonian and Laird test, with Cochran Q statistics. The results of the only group included in this meta-analysis were represented using Forest plots and showed the differences observed between the mean values of the degree of the effect in the intervention groups versus the control groups, including the respective confidence intervals. A means differential and a 95% confidence interval were used, and the level of significance was p < 0.05.

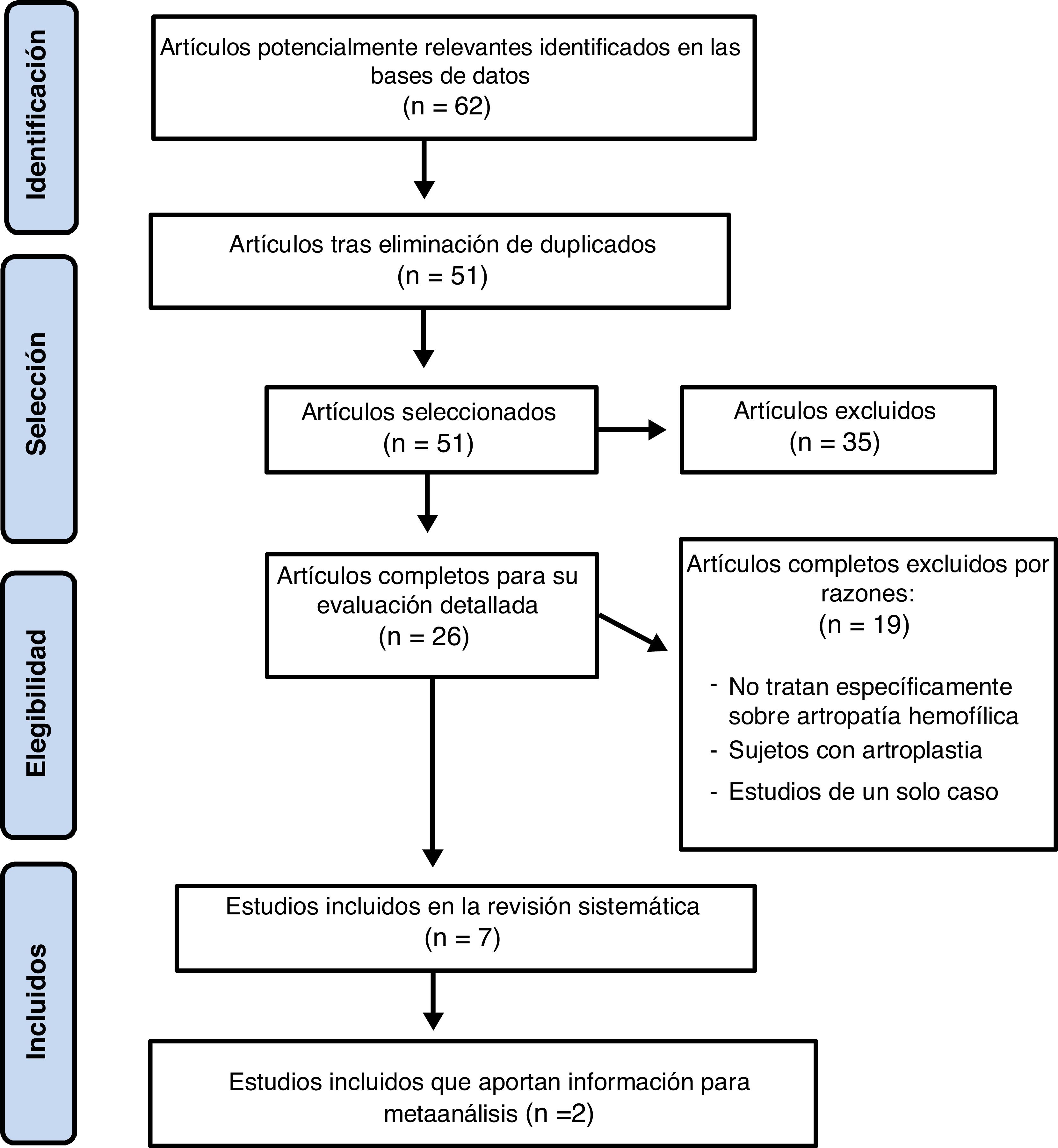

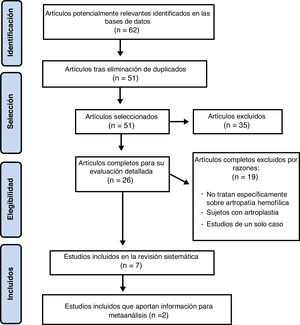

ResultsThe selection of the articles included in this review is represented in the detailed flowchart in Fig. 1. Upon implementation of the search and selection strategy, a total of 55 of the 62 potentially valid publications were rejected because they failed to comply with the inclusion criteria applicable for this review. Following the verification for compliance with the criteria and after eliminating the duplicate articles, a total of seven trials on physical interventions in subjects diagnosed with HA were selected, for detailed analysis. Due to the diversity of CTs, only two randomized clinical trials (RCTs) on physical interventions for improving pain sere included in the meta-analysis for statistical comparisons.

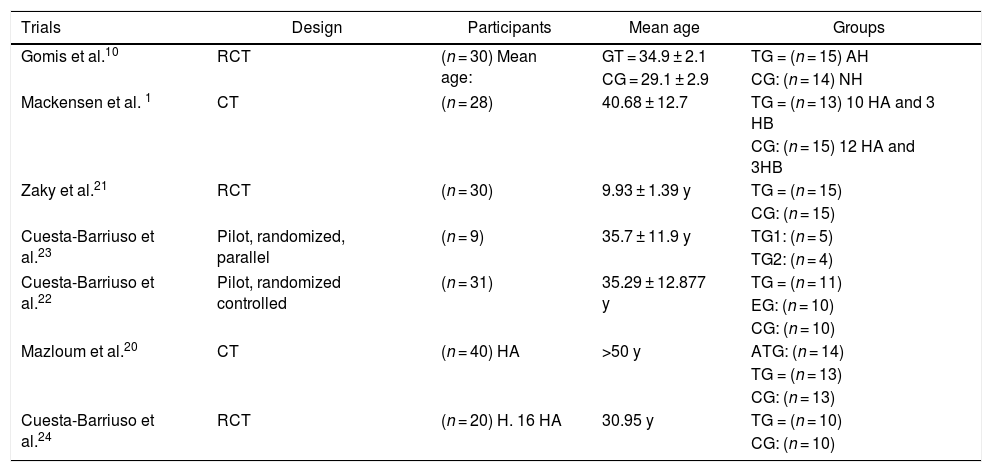

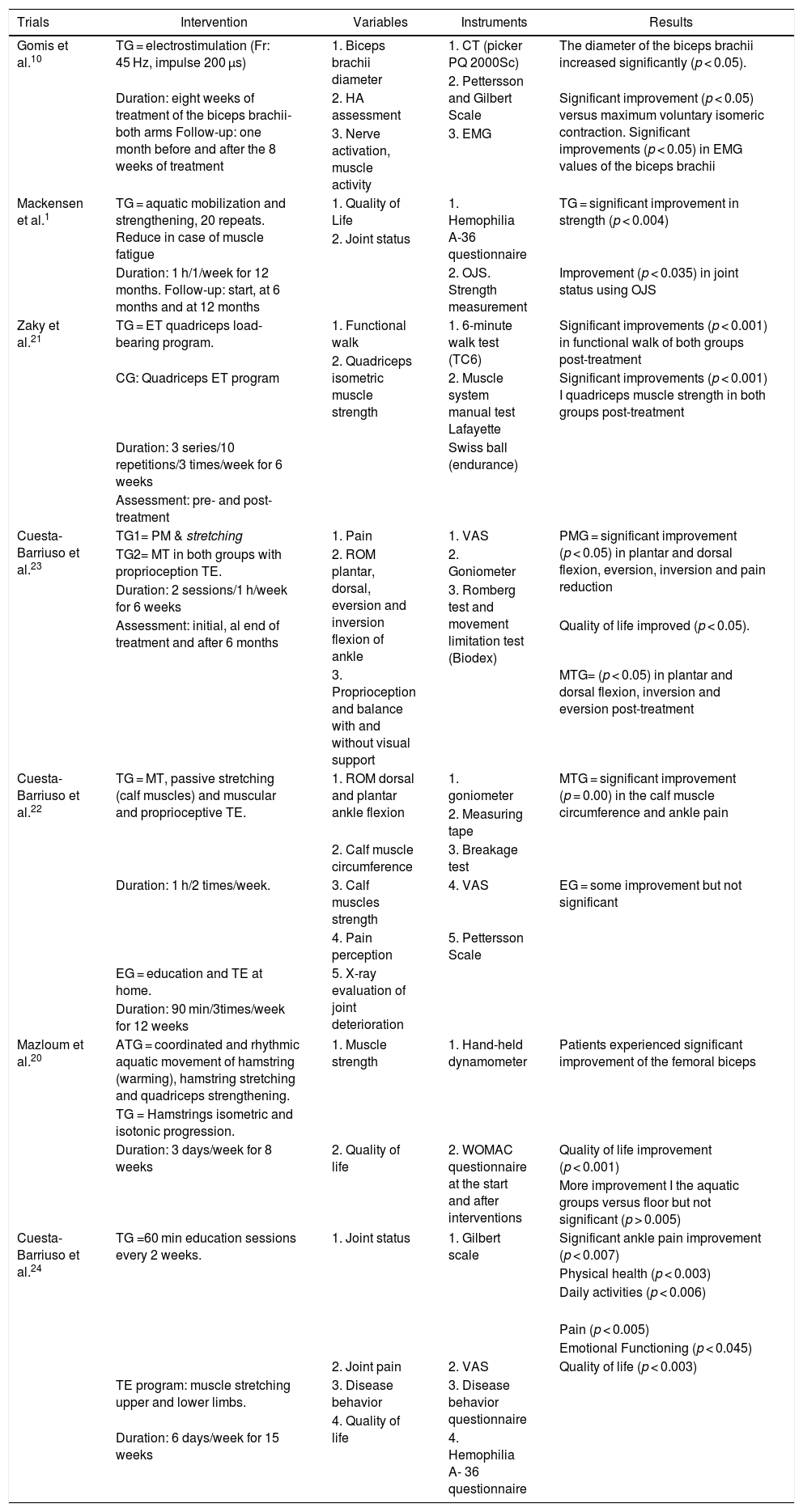

Table 2 illustrates the principal characteristics of the subjects included in this review, and Table 3 shows the main characteristics of the interventions.

Key characteristics of the participants.

| Trials | Design | Participants | Mean age | Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gomis et al.10 | RCT | (n = 30) Mean age: | GT = 34.9 ± 2.1 | TG = (n = 15) AH |

| CG = 29.1 ± 2.9 | ||||

| CG: (n = 14) NH | ||||

| Mackensen et al. 1 | CT | (n = 28) | 40.68 ± 12.7 | TG = (n = 13) 10 HA and 3 HB |

| CG: (n = 15) 12 HA and 3HB | ||||

| Zaky et al.21 | RCT | (n = 30) | 9.93 ± 1.39 y | TG = (n = 15) |

| CG: (n = 15) | ||||

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.23 | Pilot, randomized, parallel | (n = 9) | 35.7 ± 11.9 y | TG1: (n = 5) |

| TG2: (n = 4) | ||||

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.22 | Pilot, randomized controlled | (n = 31) | 35.29 ± 12.877 y | TG = (n = 11) |

| EG: (n = 10) | ||||

| CG: (n = 10) | ||||

| Mazloum et al.20 | CT | (n = 40) HA | >50 y | ATG: (n = 14) |

| TG = (n = 13) | ||||

| CG: (n = 13) | ||||

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.24 | RCT | (n = 20) H. 16 HA | 30.95 y | TG = (n = 10) |

| CG: (n = 10) |

CT: controlled trial; RCT: randomized controlled trial; CG: control group; TG: treatment group; ATG: aquatic treatment group; TG1: treatment group 1; TG2: treatment group 2; HA: hemophilia A; HB: hemophilia B; NH: non-hemophilic.

Characteristics of the trials included.

| Trials | Intervention | Variables | Instruments | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gomis et al.10 | TG = electrostimulation (Fr: 45 Hz, impulse 200 μs) | 1. Biceps brachii diameter | 1. CT (picker PQ 2000Sc) | The diameter of the biceps brachii increased significantly (p < 0.05). |

| 2. Pettersson and Gilbert Scale | ||||

| Duration: eight weeks of treatment of the biceps brachii-both arms Follow-up: one month before and after the 8 weeks of treatment | 2. HA assessment | |||

| Significant improvement (p < 0.05) versus maximum voluntary isomeric contraction. Significant improvements (p < 0.05) in EMG values of the biceps brachii | ||||

| 3. Nerve activation, muscle activity | 3. EMG | |||

| Mackensen et al.1 | TG = aquatic mobilization and strengthening, 20 repeats. Reduce in case of muscle fatigue | 1. Quality of Life | 1. Hemophilia A-36 questionnaire | TG = significant improvement in strength (p < 0.004) |

| 2. Joint status | ||||

| 2. OJS. Strength measurement | ||||

| Improvement (p < 0.035) in joint status using OJS | ||||

| Duration: 1 h/1/week for 12 months. Follow-up: start, at 6 months and at 12 months | ||||

| Zaky et al.21 | TG = ET quadriceps load-bearing program. | 1. Functional walk | 1. 6-minute walk test (TC6) | Significant improvements (p < 0.001) in functional walk of both groups post-treatment |

| 2. Quadriceps isometric muscle strength | ||||

| 2. Muscle system manual test Lafayette | ||||

| CG: Quadriceps ET program | ||||

| Significant improvements (p < 0.001) I quadriceps muscle strength in both groups post-treatment | ||||

| Swiss ball (endurance) | ||||

| Duration: 3 series/10 repetitions/3 times/week for 6 weeks | ||||

| Assessment: pre- and post-treatment | ||||

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.23 | TG1= PM & stretching | 1. Pain | 1. VAS | PMG = significant improvement (p < 0.05) in plantar and dorsal flexion, eversion, inversion and pain reduction |

| TG2= MT in both groups with proprioception TE. | 2. ROM plantar, dorsal, eversion and inversion flexion of ankle | 2. Goniometer | ||

| 3. Romberg test and movement limitation test (Biodex) | ||||

| Duration: 2 sessions/1 h/week for 6 weeks | ||||

| Assessment: initial, al end of treatment and after 6 months | ||||

| Quality of life improved (p < 0.05). | ||||

| 3. Proprioception and balance with and without visual support | ||||

| MTG= (p < 0.05) in plantar and dorsal flexion, inversion and eversion post-treatment | ||||

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.22 | TG = MT, passive stretching (calf muscles) and muscular and proprioceptive TE. | 1. ROM dorsal and plantar ankle flexion | 1. goniometer | MTG = significant improvement (p = 0.00) in the calf muscle circumference and ankle pain |

| 2. Measuring tape | ||||

| 2. Calf muscle circumference | 3. Breakage test | |||

| 3. Calf muscles strength | ||||

| Duration: 1 h/2 times/week. | 4. VAS | EG = some improvement but not significant | ||

| 4. Pain perception | ||||

| 5. Pettersson Scale | ||||

| 5. X-ray evaluation of joint deterioration | ||||

| EG = education and TE at home. | ||||

| Duration: 90 min/3times/week for 12 weeks | ||||

| Mazloum et al.20 | ATG = coordinated and rhythmic aquatic movement of hamstring (warming), hamstring stretching and quadriceps strengthening. | 1. Muscle strength | 1. Hand-held dynamometer | Patients experienced significant improvement of the femoral biceps |

| TG = Hamstrings isometric and isotonic progression. | ||||

| Duration: 3 days/week for 8 weeks | ||||

| 2. Quality of life | 2. WOMAC questionnaire at the start and after interventions | |||

| Quality of life improvement (p < 0.001) | ||||

| More improvement I the aquatic groups versus floor but not significant (p > 0.005) | ||||

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.24 | TG =60 min education sessions every 2 weeks. | 1. Joint status | 1. Gilbert scale | Significant ankle pain improvement (p < 0.007) |

| Physical health (p < 0.003) | ||||

| Daily activities (p < 0.006) | ||||

| Pain (p < 0.005) | ||||

| Emotional Functioning (p < 0.045) | ||||

| Quality of life (p < 0.003) | ||||

| 2. Joint pain | ||||

| 2. VAS | ||||

| 3. Disease behavior | 3. Disease behavior questionnaire | |||

| TE program: muscle stretching upper and lower limbs. | ||||

| 4. Quality of life | ||||

| 4. Hemophilia A- 36 questionnaire | ||||

| Duration: 6 days/week for 15 weeks |

HA: hemophilic arthropathy; CT: controlled trial; RCT: randomized controlled trial; ET: therapeutic exercise; VAS: visual analogue scale; CG: control group; Fr: frequency; EG: education group; TG: treatment group; ATG: aquatic treatment group; TG1: treatment group 1; TG2: treatment group 2; HA: hemophilia A; HB: Hemophilia B; PM: passive mobilization; NH: non-hemophilic; OJS: WFH orthopedic joint score; ROM: range of movement; MT: manual therapy; TTO: treatment; WOMAC: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities.

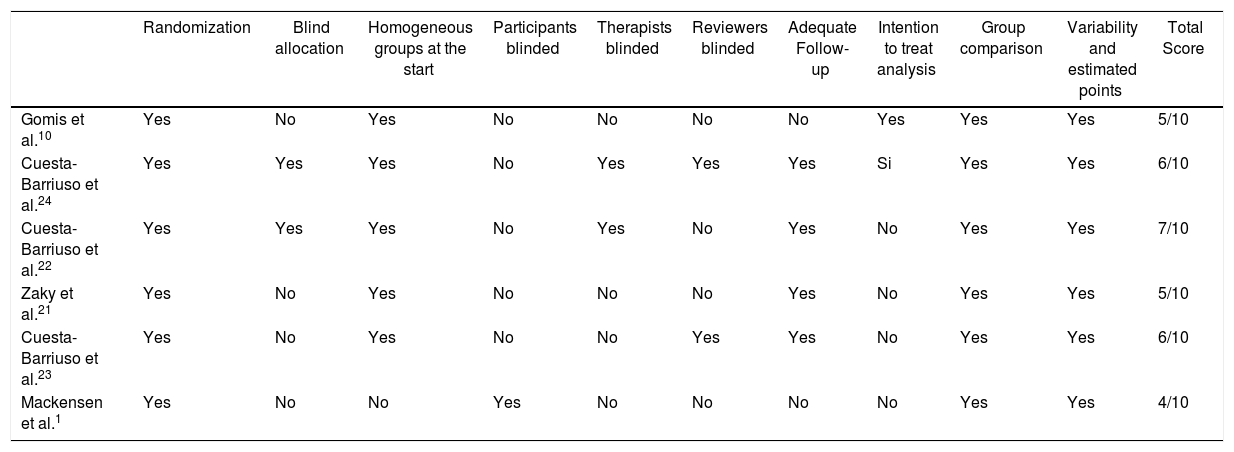

Of all the Quality Assessments used to complete this systematic review, the evaluation of the risk of bias was conducted in six of the seven trials included. The trial by Mazloum et al.20 is written in Farsi, and so it could not be evaluated. All of the trials received a score ≥5 in the PEDro scale, except for the trial by Mackensen et al.1 which scored 4; So the trials could be considered average to high methodological quality and low to medium risk of bias, as shown in Table 4.

Methodological assessment according to PEDro Scale.

| Randomization | Blind allocation | Homogeneous groups at the start | Participants blinded | Therapists blinded | Reviewers blinded | Adequate Follow-up | Intention to treat analysis | Group comparison | Variability and estimated points | Total Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gomis et al.10 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5/10 |

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.24 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Si | Yes | Yes | 6/10 |

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.22 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7/10 |

| Zaky et al.21 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 5/10 |

| Cuesta-Barriuso et al.23 | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6/10 |

| Mackensen et al.1 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 4/10 |

With regards to the age of the participants, only one of the trials21 included minors. The rest of the trials were on adults.1,10,20,22–24 It should be emphasized that in the CT by Cuesta-Barriuso et al.23 only new subjects participate and therefore the results should be considered with caution.

With regards to the type of hemophilia, three1,22,23 of the seven CTs included hemophilia type A and type B subjects. Three articles10,20,24 only selected subjects with hemophilia A and one other article fails to specify the type of hemophilia of the participants. One trial10 selected non-hemophilia patients for the control group.

In terms of the affected joints and the target areas for intervention, the articles specify that the subjects present arthropathy in one or both ankles.22,23 Five20–24 of the seven clinical trials administered the treatment in the lower limbs10; the ankle joint was the most frequently affected. The calf muscles,22 the hamstrings, the femoral biceps20 and the quadriceps20,21 muscles were also treated. One CT10 focused on the upper limbs, treating the biceps and triceps brachii. Another trial17 administered treatment to both the upper and the lower limbs.

InterventionThe control group did not receive any treatment in the CTs reviewed. Patients in this group continued with their daily activities, except for one21 that implemented a therapeutical exercise (TE) program.

Furthermore, six of the seven trials1,20–24 used TE as a treatment method for the treatment group; one trial1 implemented aquatic TE. Two trials22,23 conducted proprioception TE as complementary therapy to passive mobilization23 and to manual therapy (MT).22,23 In one trial21 weight bearing TE was practiced. In two CTs20,24 TE with stretching was practiced. In one article 1 passive mobilization and strengthening was performed. Moreover, two of the six trials22,24 included education sessions conducted by a physical therapist. One trial10 used electrostimulation as a treatment approach for arthropathy.

Physical variables analyzedThe principal variables analyzed were: pain, joint status, muscle strength, muscle diameter, ROM, and quality of life.

PainA meta-analysis was conducted using pain as a variable, including two articles, one RCT24 and one pilot study.22 Both studies compare a treatment group versus a control group and use the same measurement instrument: VAS. The RCT24 did the measurement in three joints (ankle, knee and elbow), whilst the pilot study22 just measured one joint (ankle). The RCT24 achieved significant ankle pain improvements (p < 0.007) as a result of MT, a TE program including muscle stretching and educations sessions. The other trial22 reported that MT and stretching result in significant pain relief (p = 0.00). Fig. 2 shows the information used from each study to conduct the meta-analysis, in addition to the results in a Forest plot. The VAS scores of both trials were used for the different sites measured (ankle,22,24 knee24 and elbow24).

Joint statusThese variables were measured in four articles.1,10,22,24 One study used the Pettersson scale22 and found improvements, though not significant, with MT and muscle and proprioceptive TE. However, one RCT used the Gilbert scale and achieved significant improvements (p < 0.004)24 with the TE program, muscle stretching, and education sessions. Moreover, another RCT10 used both scales to measure, but failed to achieve any improvement with electrostimulation therapy. Finally, one trial1 used the WFH Orthopaedic Joint Score (OJS) and achieved significant improvements (p < 0.035) with mobilization and strengthening.

Muscle strengthTwo articles20,21 measured muscle strength. One RCT21 measured with the Lafayette test and achieved significant improvements (p < 0.001) in muscle strength of the quadriceps after treatment with a weight-bearing TE program. However, the other study20 measured with a hand-held dynamometer and the patients improved their femoral biceps strength with aquatic TE, but the improvement was not significant.

Muscle diameterTwo articles measured the muscle diameter using different techniques10,22: one RCT used CT-scan10 and the other22 used a measuring tape. Both studies achieved significant improvements.10,22 The RCT10 achieved significant improvements (p < 0.05) in the diameter of the biceps brachii using electrostimulation and the other study22 (p = 0.00) improved the calf circumference using MT and muscular and proprioceptive TE.

Range of motion (ROM)Two studies22,23 measured the dorsal and plantar flexion of the ankle; both used a goniometer.22,23 One of the studies23 achieved significant improvements (p < 0.05) using passive mobilization, muscle stretching and MT. However, the other trial22 failed to achieve any improvement with MT and TE.

Quality of lifeThree articles measured quality of life.1,20,24 Two studies measured quality of life with the Hemophilia A-36 questionnaire.1,24 A significant improvement was reported in one RCT (p < 0.003)24 using a TE program stretching the upper and lower extremities. In the other CT,1 aquatic TE was performed, and no improvements were recorded.

FunctionalityOne study administered the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (Womac) questionnaire.20 There were some improvements after aquatic training, at the end of the follow-up period of five years, but these improvements were not significant (p > 0.005).

DiscussionThe objective of this review was to analyze the scientific evidence on the efficacy of physical rehabilitation with regards to HA. The results reported show that this intervention results in improvements in the physical impairments resulting from HA, as well as in the quality of life of patients with hemophilia. Most clinical trials1,10,20,22–24 have been conducted in adults with type A HA and in the joints of the lower extremities.

In terms of the different types of interventions, therapeutic exercise has been the most widely used intervention.1,20–24 TE has achieved significant improvements in strength and joint status1; in ankle ROM, pain22,24 and quality of life13,21,24; in the muscle diameter of the calf muscles22; in gait and muscle strength of the quadriceps.21

The positive pain results reported in the trials by Cuesta-Barriuso et al.22,24 should be particularly noted, since both trials exhibit a high methodological quality and the results have been statistically assessed through meta-analyses. In both trials, home rehabilitation programs19,22 and MT,22 accomplish significant improvements in ankle pain perception,19,22 and in terms of quality of life, perception about the evolution of the disease19 and the muscle diameter of the hamstrings.22

The trial by Gomis et al.,10 with a high methodological quality based on PEDro scale, uses an 8-week electrostimulation program in patients with type A HA, and achieves significant improvements in the muscle diameter and in the EMG activity of the biceps brachii.

Finally, it should be highlighted that in the studies analyzed in this review, the authors fail to mention any potential adverse effects.

The results obtained should be considered by healthcare practitioners, by patients and by decision-makers in hospital settings. As mentioned in the introduction, 66% of the patients with HA are not receiving proper treatment11; therefore, there is a need to raise awareness about the benefits of physical therapy for this population.

We experienced a number of drawbacks when conducting this systematic review. The heterogeneity, the small number of articles identified and the small sample sizes, hinder any potential comparisons and hence the results should be viewed with caution. It was only possible to do a meta-analysis on one of the variables measured (pain), with a very small number of patients (51). Furthermore, the databases selected could have influenced the results; some databases were missing, such as grey literature, CINAHL, EMBASE or Cochrane. Including just English and Spanish articles may have been an additional limitation.

The use of randomized clinical trials and the fact that more than fifty percent achieved a high PEDro score, supports the reliability of the review, since this type of study is the most appropriate to assess the efficacy and the value of any intervention. Nonetheless, the risk of outcome bias was not assessed; in other words, the possibility of bias of the accumulated evidence with regards to pain outcome was not systematically analyzed.

ConclusionsThis systematic review evidenced the efficacy of rehabilitation for improving HA, particularly using TE. Moreover, potential benefits were identified in various areas, such as pain, joint status, muscle strength and muscle diameter, range of movement and quality of life. Further studies of high methodological quality, following diverse protocols and using larger samples, measuring similar variables, and assessing long term effects will certainly be welcome.

FinancingNo funding or grant was received from any public agency, business or non-profit institution.

Please cite this article as: Pacheco-Serrano AI, Lucena-Antón D, Moral-Muñoz JA. Rehabilitación física en pacientes con artropatía hemofílica: revisión sistemática y metaanálisis sobre dolor. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:124–133.