Fibromyalgia has a high degree of co-occurrence with a number of conditions. The association of fibromyalgia, headache and mood disorders is well observed.

ObjectiveTo analyze the relationship between these manifestations, exploring whether the quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia is influenced by the presence of depressive symptoms and chronification of headache.

Materials and methodsA retrospective observational cross-sectional study was carried out to determine the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia presenting with headache and/or depressive symptoms. The samples were evaluated using the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and Symptom Severity (SS) questionnaires to confirm the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Quality of life and level of depressive symptoms were assessed, respectively, by the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).

ResultsA total of 120 patients (3 men and 117 women) diagnosed with fibromyalgia were interviewed, with ages ranging from 23 to 65 years. The most common primary headache was chronic migraine (45%). While depressive symptoms was observed in 118 patients (98.33%). The factors degree of depressive symptoms and headache chronicity were marginally significant in explaining the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia.

ConclusionsFaced with a disease with such a possibility of being associated with other complex conditions, multidisciplinary monitoring becomes a preponderant factor in the treatment of the entire patient.

La fibromialgia tiene un alto grado de co-ocurrencia con una serie de condiciones. La asociación de fibromialgia, dolor de cabeza y trastornos del estado de ánimo es bastante conocida.

ObjetivoAnalizar la relación entre estas manifestaciones, explorando si la calidad de vida en los pacientes con fibromialgia se ve influida por la presencia de síntomas depresivos y la cronificación de la cefalea.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional transversal retrospectivo para determinar la calidad de vida de los pacientes con fibromialgia que presentan cefalea o síntomas depresivos. Las muestras se evaluaron utilizando los cuestionarios de índice de dolor generalizado (WPI) y severidad de los síntomas (SS) para confirmar el diagnóstico de fibromialgia. La calidad de vida y el nivel de síntomas depresivos se evaluaron, respectivamente, mediante el Cuestionario de Impacto de la Fibromialgia (FIQ) y el Cuestionario de Salud del Paciente-9 (PHQ-9).

ResultadosSe entrevistó a un total de 120 pacientes (3 varones y 117 mujeres) diagnosticados de fibromialgia, con edades comprendidas entre los 23 y los 65 años. La cefalea primaria más común fue la migraña crónica (45%), mientras que los síntomas depresivos se observaron en 118 pacientes (98,33%). Los factores grado de síntomas depresivos y cronicidad de la cefalea fueron marginalmente significativos para explicar la calidad de vida de los pacientes con fibromialgia.

ConclusionesAnte una enfermedad con tal posibilidad de estar asociada a otras condiciones complejas, el seguimiento multidisciplinario se convierte en un factor preponderante en el tratamiento de todo paciente.

Fibromyalgia has a high degree of co-occurrence with a number of visceral, myofascial and craniofacial pain conditions.1 Among these comorbidities, the association of fibromyalgia and headache is well observed, especially in the case of headache with a large number of monthly or chronic attacks.2 It is considered chronic when the patient has at least 15 crisis days per month.1 Another condition found in this disease is mood disorders, with fibromyalgia being considered a risk factor for depression.3 However, the reasons behind these associations, possibly complex and multifactorial, still remain the subject of active investigation.1

Therefore, the importance of this study is reinforced by the need for new research on this topic. In such a way that increasing awareness about this comorbidity can provide critical and practical perspectives during patient management.4 Since the coexistence of several pain conditions in the same patient can involve significant interactions of symptoms and complicate the diagnosis.1

The objective of this study was to analyze the relationship between these manifestations, exploring whether the quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia is influenced by the presence of depressive symptoms and chronification of headache.

Patients and methodsStudy design and patientsThis was a retrospective, observational and cross-sectional study. The study population comprised a non-random, convenience sampling, consisting of the first 421 patients with fibromyalgia diagnosed and treated by rheumatologists at a university hospital. Data for this study was collected from March 2022 to February 2023.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaPatients aged between 18 and 65 years old diagnosed with fibromyalgia, according to the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR, 2016) were included in the study. To obtain consistent and valid data, the study excluded patients with secondary headaches and/or cognitive disorders that made it difficult to understand the interview and pregnant women. Having or not immune-mediated comorbidities was not considered an inclusion or exclusion criterion.

Sample size calculationIt is estimated that the prevalence of headache in patients with fibromyalgia is high, with values between 45% and 80% (SILVA, 2011). For the expected prevalence of 45%, the sample size required was 96 patients, with a margin of error or absolute precision of at least 10% in the prevalence estimate and with 95% confidence. This sample size was calculated using the Scalex SP calculator.5

Data collectDuring data collection, 421 patients were evaluated, of which only 120 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Three hundred and four were excluded for the following reasons: did not answer the phone (n=119), refused to participate in the research (n=176), death (n=3), pregnancy (n=1), secondary headache (n=1) and low instructional level (n=1).

The 120 patients were assessed using the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) and Symptom Severity (SS) questionnaires to evaluate, respectively, the reported location of muscle pain and the degree of severity of associated symptoms.2 These data are evaluated together to diagnose fibromyalgia. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) to analyze, respectively, quality of life and level of depressive symptoms. The FIQ consists of 19 questions, which measure functional capacity, work situation, psychological disorders, physical and painful symptoms. The greater the impact disease, the higher the score found.2 The PHQ-9 is also an instrument validated, used as screening for major depressive episodes in studies epidemiological analysis, the definitive diagnosis of the disease can only be established through consultation with mental health professionals.6 These questionnaires are validated and were administered by a rheumatologist. And finally, those who complained of headache were subjected to a questionnaire with questions about headache variables. These questions aimed to diagnose which type of primary headache the participant has, according to the Headache Classification, third edition (IHS, 2018). Frequency, intensity, duration, character, location of pain and associated symptoms are considered.

Statistical analysisThe R software, version 4.2.2, was used for statistical analysis. The characterization of participants regarding gender, type of headache, associated rheumatological comorbidities and degree of depressive symptoms was carried out using absolute frequencies (n) and percentages (%) and presented in frequency tables. The age variable was described using mean and variation. In the multivariate analysis, a multiple beta regression model was used adjusted considering the impact of fibromyalgia on quality of life (FIQ) as the dependent variable. The FIQ was adjusted for age, sex, presence of comorbidity, degree of depressive symptoms and headache chronicity. The FIQ was used as a continuous variable in the interval (0.1), for this the transformation FIQ*=(FIQ−a)/(b−a) was used. The estimates of the model coefficients (β) obtained by the maximum likelihood method, the asymptotic standard errors (EP), the p value calculated by the Wald test were presented in a table. Additionally, the odds ratio (OR) and its range 95% confidence were used to express the magnitude of the effect of covariates in quality of life. The significance level adopted was 5% and the hypotheses tested were all bilateral.

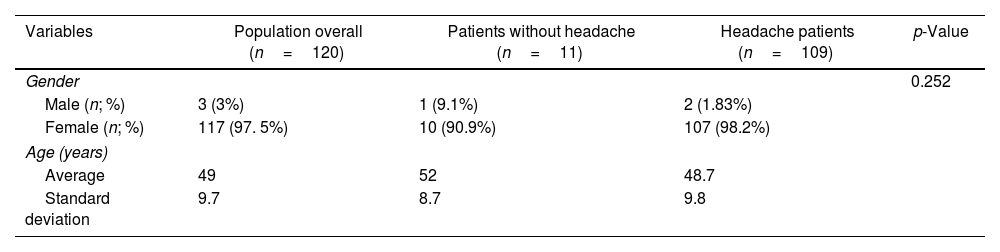

ResultsOf the 421 patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, 120 were included in the study, 2.5% (3/120) men and 97.5% (117/120) women, whose ages ranged from 23 to 65 years, as shown in Table 1.

Distribution of sex and age, according to diagnosis of 120 patients with fibromyalgia.

| Variables | Population overall (n=120) | Patients without headache (n=11) | Headache patients (n=109) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.252 | |||

| Male (n; %) | 3 (3%) | 1 (9.1%) | 2 (1.83%) | |

| Female (n; %) | 117 (97. 5%) | 10 (90.9%) | 107 (98.2%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Average | 49 | 52 | 48.7 | |

| Standard deviation | 9.7 | 8.7 | 9.8 | |

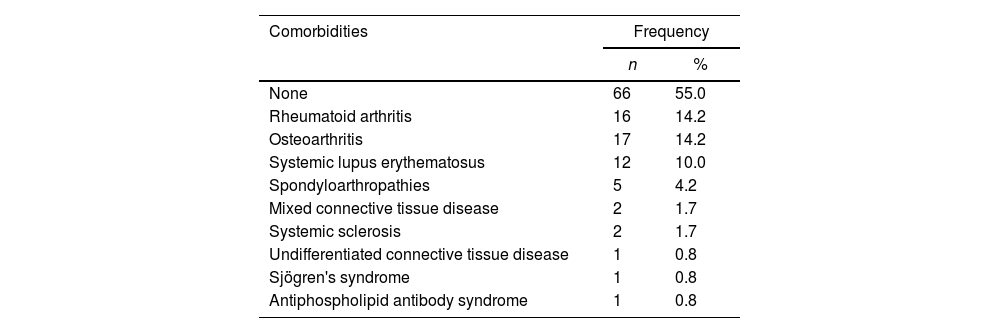

Assessing the presence of rheumatological comorbidities, it was found that more than half of the patients (55%) did not have any other rheumatological disease other than fibromyalgia and/or soft tissue diseases (Table 2).

Distribution of rheumatological comorbidities in 120 patients with fibromyalgia.

| Comorbidities | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| None | 66 | 55.0 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 16 | 14.2 |

| Osteoarthritis | 17 | 14.2 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 12 | 10.0 |

| Spondyloarthropathies | 5 | 4.2 |

| Mixed connective tissue disease | 2 | 1.7 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 2 | 1.7 |

| Undifferentiated connective tissue disease | 1 | 0.8 |

| Sjögren's syndrome | 1 | 0.8 |

| Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | 1 | 0.8 |

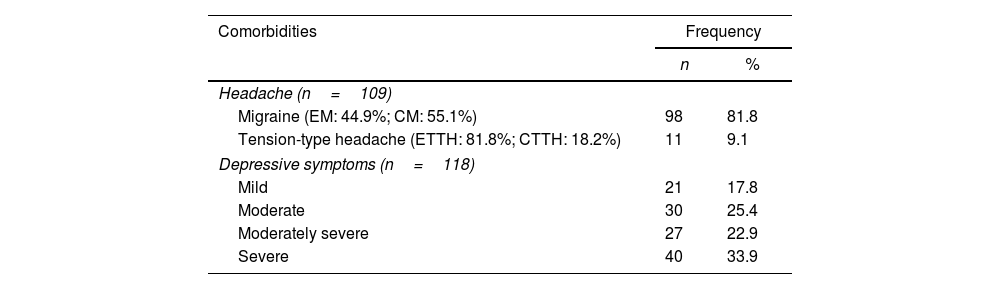

Of the 120 patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, 81.8% (98/120) had migraine; 9.1% (11/120), tension-type headache; and 9.1% (11/120) did not complain of headache. Of the patients with migraine, 55.1% (54/98) had ≥15 headache days per month. Of these, 17.8% (21/118) had mild depressive symptoms; 25.4% (30/118), moderate; 22.9% (27/118), moderately severe; and 33.9% (40/118), severe. Of the 118 patients with depressive symptoms, only 49.1% received psychiatric care (Table 3).

Distribution of neurological and psychiatric comorbidities in 120 patients with fibromyalgia.

| Comorbidities | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Headache (n=109) | ||

| Migraine (EM: 44.9%; CM: 55.1%) | 98 | 81.8 |

| Tension-type headache (ETTH: 81.8%; CTTH: 18.2%) | 11 | 9.1 |

| Depressive symptoms (n=118) | ||

| Mild | 21 | 17.8 |

| Moderate | 30 | 25.4 |

| Moderately severe | 27 | 22.9 |

| Severe | 40 | 33.9 |

Note: ETTH, Episodic Tension-type headache; CTTH, Chronic Tension-type headache; EM, episodic migraine; CM, chronic migraine.

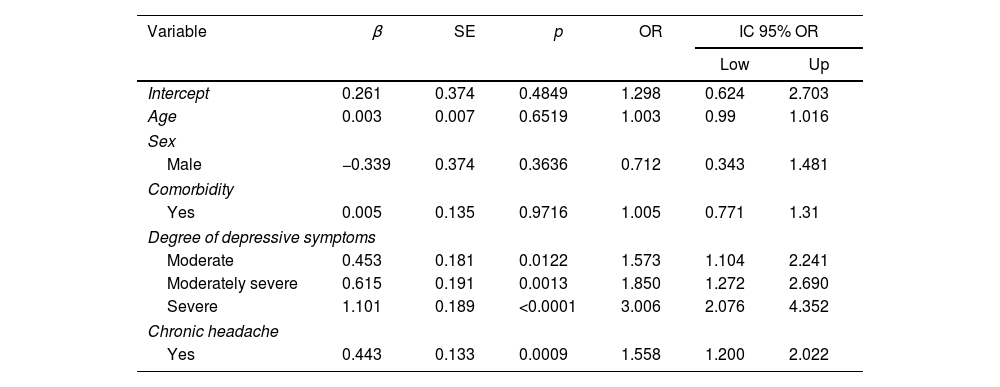

In Table 4 we have the parameter estimates of a multiple beta regression adjusted to the data. The quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia (FIQ) was adjusted for age, sex, presence of any comorbidity, degree of depressive symptoms and chronicity of the headache. The factors degree of depressive symptoms and headache chronicity were marginally significant in explaining the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia. From the adjusted model, it is noted that: the chance of worsening quality of life of patients with moderate depressive symptoms is 1.573 times the chance of patients with absent or mild depressive symptoms, keeping other variables fixed (OR: 1.573; 95% CI OR: 1.104–2.241; p=0.0122); the chance of a worsening in the quality of life of patients with moderately severe depressive symptoms is 1.85 times the chance of patients with absent or mild depressive symptoms, keeping other variables fixed (OR: 1.850; 95% CI OR: 1.272–2.690; p=0.0013); the chance of a worsening in the quality of life of patients with severe depressive symptoms is 3.006 times the chance of patients with absent or mild depressive symptoms, keeping the other variables fixed (OR: 3.006; 95% CI OR: 2.076–4.352; p<0.0001); Furthermore, the chance of worsening the quality of life of patients with chronic headache is 1.558 times the chance of patients without chronic headache, keeping the other variables fixed (OR: 1.558; 95% CI OR: 1.200–2.022; p=0.0009).

Variables related to quality of life in people with fibromyalgia (beta regression).

| Variable | β | SE | p | OR | IC 95% OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Up | |||||

| Intercept | 0.261 | 0.374 | 0.4849 | 1.298 | 0.624 | 2.703 |

| Age | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.6519 | 1.003 | 0.99 | 1.016 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | −0.339 | 0.374 | 0.3636 | 0.712 | 0.343 | 1.481 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Yes | 0.005 | 0.135 | 0.9716 | 1.005 | 0.771 | 1.31 |

| Degree of depressive symptoms | ||||||

| Moderate | 0.453 | 0.181 | 0.0122 | 1.573 | 1.104 | 2.241 |

| Moderately severe | 0.615 | 0.191 | 0.0013 | 1.850 | 1.272 | 2.690 |

| Severe | 1.101 | 0.189 | <0.0001 | 3.006 | 2.076 | 4.352 |

| Chronic headache | ||||||

| Yes | 0.443 | 0.133 | 0.0009 | 1.558 | 1.200 | 2.022 |

Note: Reference categories: sex (female), comorbidity (no), degree of depressive symptoms (absence or mild) and chronic headache (no). Dependent variable: FIQ*: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire. β: regression coefficient. SE: standard error. p: p-value (descriptive level). OR=exp(β): odds ratio. 95% CI OR: 95% confidence interval for the OR. Low: lower limit of the 95% CI and up: upper limit of the 95% CI.

Although the prevalence of fibromyalgia is much higher in women than in men, there is no literature available on the role of sex hormones in fibromyalgia.7 In this study, a prevalence of females was found in the sample with and without headache complaints.

A predominance of fibromyalgia not associated with other rheumatic diseases was also observed (55%). This comorbidity is already well established, demonstrating a prevalence of up to 25% of fibromyalgia. It is therefore known that, with the exception of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, this association is demonstrated with worse activity scores, when compared to patients without associated fibromyalgia.8

Headaches are a considerably frequent comorbidity in patients with fibromyalgia, reported in about half of patients with fibromyalgia.4 This study observed a prevalence of 90.83%. Migraine is the primary headache with the highest association (81.67%). However, these data are discordant between studies. There are those who show that tension-type headache is the most prevalent1,4). While others, migraine – varying between 45% and 80%.9 The reasons justifying this association are still under investigation.1 Edwards et al., for example, reported the possible role of central sensitization in pathophysiology. This theory is justified because fibromyalgia and migraine are painful syndromes characterized by changes in the central processing of sensory stimuli and a decrease in the pain threshold. This data is not observed when it comes to tension headaches.10 Regardless of the true justification for such comorbidity, the importance of prophylactic treatment of chronic headache stands out, when well indicated by a specialist in the field. Likewise, it is suggested that more studies are needed to evaluate the possibility of medications associated with the simultaneous control of both conditions.

It was also observed that the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia was significantly impacted as the levels of depressive symptoms worsened. Depression can be found in both headache patients and fibromyalgia patients. Pathophysiologically, this comorbidity is explained by the dysregulation of neurotransmitters that can precipitate the various symptoms and comorbidities associated with fibromyalgia, including pain, comorbid depression and behavioral abnormalities.7 While the association with chronicity may be explained by the fact that certain predisposing factors, including depression and stressful life events, may lower the threshold for headache attacks and thus increase the risk of chronicity.11 Therefore, there are sufficient epidemiological and pathophysiological data to suggest screening for depressive symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia. Because treating depressive symptoms through specialized care can mean fewer triggers for fibromyalgia pain.

The headache chronicity factor was also marginally significant in explaining the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia. However, it is worth highlighting that of the 118 patients with depressive symptoms, only 49.1% received psychiatric care. This data can be considered a confounding factor for the deterioration of quality of life, regardless of whether there is a headache or not. Since the association of debilitating painful disorders, such as fibromyalgia and headache, with mood disorders can simultaneously impact the quality of life of these patients.12 An integrative review published in 2019 showed that pain is the main limiting factor for quality of life. In addition to the pain crisis, other issues are triggered, such as the difficulty in maintaining autonomy even in self-care, personal hygiene, improving appearance and self-esteem.13 Although no similar and current study was found that specifically analyzes the Latin American population, a cross-sectional study published in 2021 demonstrated that patients with fibromyalgia had a worse quality of life (EQ-VAS 57.7±26.2), when compared to other diseases with rheumatological causes.14

It is also worth noting that the design of this study does not allow evaluating the meaning of the associations found. Only a study with a prospective design could do this.

ConclusionsThe bibliographic study allowed us to conclude that headache complaints are common in patients with fibromyalgia. Migraine is the most common primary headache. It was also noticed that the factors degree of depressive symptoms and headache chronicity were marginally significant in explaining the quality of life of patients with fibromyalgia. Faced with a disease with such a possibility of being associated with other complex conditions, multidisciplinary monitoring becomes a preponderant factor in the treatment of the entire patient.

ContributorsY. Fortes: the conception and design of the study.

W. Souza: acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data.

A. Soares: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

M.G. Sousa: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

B. Castro: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

R. Silva-Néto: final approval of the version to be submitted.

G. Uchôa: drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Beings of the Federal University of Piauí, Brazil, protocol number 5.789.344 and the National Research Ethics System, registration number 65039022.0.0000.8050. All patients signed the Free and Informed Consent Form.

FundingThere was no funding for this research.

Conflict of interestNone.