The understanding of COVID-19 progression among patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SARDs) in Latin America remains limited. This study aimed to identify risk predictors associated with poor outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with SARDs.

Materials and methodsAn observational multicentre study including patients with SARDs from Ecuador and Mexico.

ResultsA total of 103 patients (78% women), aged 52.5±17.7 years, were enrolled. The most prevalent SARDs were rheumatoid arthritis (59%) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE; 24%). Severe COVID-19 was observed in 28% of patients at admission, 43% experienced complications during follow-up, and 8% ultimately died. Mortality rates were highest in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (27%) or SLE (20%). Poor prognostic factors included acute respiratory distress syndrome (odds ratio [OR]=17.07), severe COVID-19 at admission (OR=11.45), and presence of SLE (OR=4.62). In multivariate analysis, SLE emerged as the sole predictor of mortality (OR=15.61).

ConclusionsPatients with SARDs in Latin America face significant risks of adverse COVID-19 outcomes, with SLE being a major risk factor for mortality.

El conocimiento sobre cómo progresa la COVID-19 en los pacientes con enfermedades reumáticas autoinmunes sistémicas (ERAS) en América Latina es limitado. El objetivo fue identificar los factores pronósticos para la COVID-19 en los pacientes con ERAS.

Materiales y métodosEstudio multicéntrico y observacional que incluyó a pacientes diagnosticados con ERAS en Ecuador y México.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 103 pacientes (78% mujeres) con una edad promedio de 52,5±17,7 años. Las ERAS más comunes fueron artritis reumatoide (59%) y lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) (24%). Al momento de su ingreso, el 28% de los pacientes presentaron COVID-19 grave, el 43% experimentó complicaciones durante el seguimiento y el 8% falleció. Los pacientes con síndrome antifosfolípido (27%) o LES (20%) mostraron las tasas de mortalidad más altas. Los factores de mal pronóstico incluyeron síndrome de distrés respiratorio agudo (razón de momios [RM]: 17,07), COVID-19 grave al momento del ingreso (RM: 11,45) y la presencia de LES (RM: 4,62). En el análisis multivariado, el LES fue el único predictor de mortalidad (RM: 15,61).

ConclusionesEn América Latina, los pacientes con ERAS enfrentan un riesgo sustancial de desenlaces adversos al contraer la COVID-19. En esta población, el LES es el principal factor de riesgo para la mortalidad.

The emergence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Latin America has been a source of significant concern since its arrival in Brazil on February 25, 2020. The pandemic has exposed several weaknesses in the preparedness of Latin American countries to combat the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). These challenges include a lack of resources such as ventilators and intensive care units, and high rates of underlying conditions such as hypertension, obesity, and diabetes, which increase the risk of severe COVID-19. As a result, Latin American countries have experienced some of the highest case fatality rates globally.1–3

Patients diagnosed with systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases (SARDs) face an elevated susceptibility to infections due to their immune-mediated condition and the administration of immunosuppressive therapies.4–7 Emerging evidence underscores an augmented vulnerability of individuals with SARDs to SARS-CoV-2 infection.8 Factors such as advanced age, male gender, preexisting cardiovascular and pulmonary disorders, high rheumatic disease activity, and specific medications have been linked to high mortality rates in rheumatic patients.9 Although a substantial body of knowledge concerning the impact of COVID-19 on individuals with SARDs has been collected through initiatives like the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance,10 the applicability of these findings to the Latin American context remains intricate. Disparities in healthcare access and variations among nations can potentially impede the generalizability of these insights to the Latin American sphere.10 Consequently, a critical gap persists in understanding the repercussions of COVID-19 on patients with SARDs from Latin American regions.11–14

The present observational study aims to explore the consequences of acute SARS-CoV-2 infection among patients diagnosed with SARDs in Ecuador and Mexico.

Materials and methodsStudy designThis study was based on a binational, multicenter, and observational cohort design to investigate patients with pre-existing SARDs diagnosed with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. The study was conducted from June 2020 to October 2021 and included patients from various hospitals in Ecuador and Mexico. Patient evaluations were conducted either through in-person assessments or remote teleconsultations.

Patients diagnosed with SARD during hospitalization or those without a previous rheumatologist-confirmed diagnosis were excluded. Clinical data were retrieved from medical records and encompassed age, gender, disease duration, comorbidities, and rheumatic medications. Additionally, information regarding treatment during SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 symptoms, and clinical progression was collected. SARS-CoV-2 positivity was determined via an RT-PCR test using nasopharyngeal swabs taken upon admission. Serial testing for viral clearance was not conducted.

Patients were categorized based on the severity of their COVID-19 symptoms: mild (upper respiratory symptoms without pneumonia), moderate (clinical pneumonia signs without severe features), or severe (clinical pneumonia plus one of the following: respiratory rate>30 breaths/min, severe respiratory distress, or SaO2<90% with ambient air).15 Hospitalized patients were tracked from COVID-19 diagnosis to resolution or death, while non-hospitalized patients received remote follow-up.

All treatments, imaging and laboratory studies, admission to the intensive care unit, and the decision to provide mechanical ventilatory support were made at the discretion of each of the treating physicians. The decision to discharge the patient home was made solely by the treating physician according to the patient clinical status.

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was submitted to the local ethics committee, which waived formal approval due to the descriptive, retrospective, and observational nature of the study. The study was carried out taking care of the anonymity of the participants and complying with local regulations and the principles of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysisData distribution was assessed using the D’Agostino-Pearson test. Categorical variables were represented as proportions, while numerical variables were presented as mean±standard deviation. Differences between proportions were evaluated using the Chi-square test, and predictors of mortality were analyzed using Fisher's exact test, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) presented. Multiple logistic regression models were constructed to identify mortality predictors. Independent variables included gender, underlying SARD, antirheumatic therapy, comorbidities, disease severity, COVID-19, and hospitalization complications. All analyses were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Data analysis employed GraphPad Prism v.9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

ResultsA total of 103 patients were included in the study, with a mean age of 52.5±17.7 years; of these, 78% were women. The main clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) constituted the most prevalent underlying condition, accounting for 59% of patients, followed by systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in 24% of patients, systemic sclerosis in 19%, and antiphospholipid syndrome in 10%. A substantial prevalence of comorbidities was observed, including hypertension (24%) and chronic kidney disease (6%).

Clinical characteristics of patients with systemic autoimmune and rheumatic diseases.

| Total (n=103) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean±SD | 52.5±17.7 |

| Female | 81 (78) |

| Disease duration in years (information available from 95 patients) | |

| <1 year | 10 (10) |

| 1–5 years | 70 (73) |

| >5 years | 15 (15) |

| Main rheumatic disease | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 61 (59) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 25 (24) |

| Systemic sclerosis | 20 (19) |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 11 (10) |

| Sjögren's syndrome | 9 (8) |

| Systemic vasculitis | 5 (4) |

| Inflammatory myopathy | 1 (1) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 1 (1) |

| Comorbid conditions | |

| Systemic hypertension | 25 (24) |

| CKD | 7 (6) |

| Obesity | 5 (4) |

| COPD | 5 (4) |

| Diabetes | 4 (3) |

| Baseline drug therapies (information available from 95 patients) | |

| Methotrexate | 55 (57) |

| Antimalarials | 42 (44) |

| Prednisone<10mg/day | 27 (28) |

| Prednisone≥10mg/day | 20 (21) |

| Sulfasalazine | 9 (9) |

| Azathioprine | 4 (4) |

| Biologic DMARDs | 4 (4) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 3 (3) |

| Targeted synthetic DMARDs | 3 (3) |

| Leflunomide | 2 (2) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; SD, standard deviation.

Upon recruitment, 81% of patients were classified as having inactive or mildly active disease, while 19% presented with moderate to severe disease activity. Most patients (64%) were receiving treatment with at least one disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD), with methotrexate being the most commonly prescribed at baseline (57%), followed by oral glucocorticoids (49%) and antimalarials (44%). A smaller proportion of patients were on biologic (4%) or targeted synthetic (3%) DMARDs. Notably, patients who were not receiving DMARDs before the SARS-CoV-2 infection had a similar incidence of severe COVID-19 as patients who were on DMARD treatment (20% vs. 27%; p=0.472).

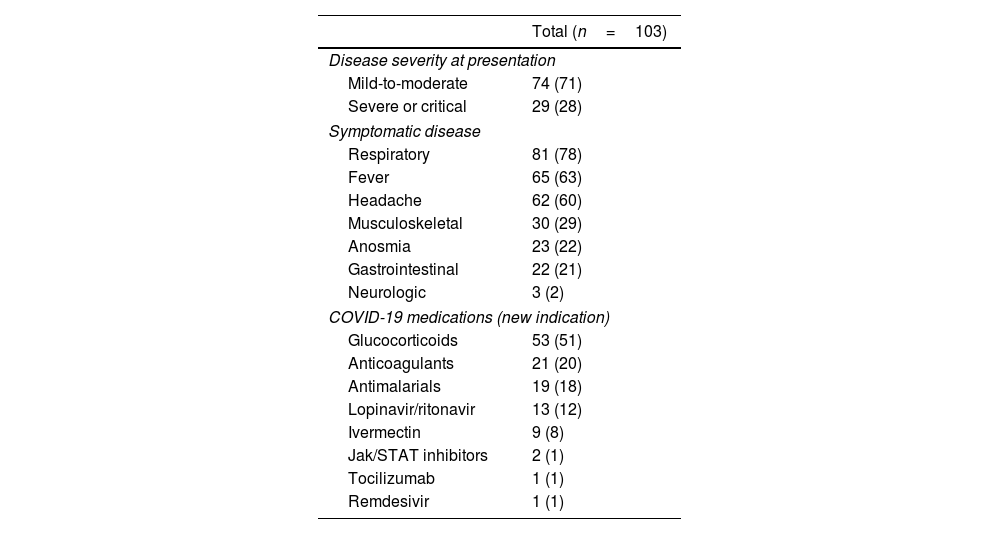

While most patients experienced symptomatic COVID-19, characterized by respiratory symptoms (78%), fever (63%), and headache (60%), the disease generally exhibited mild to moderate manifestations, necessitating hospitalization in a minority of cases (Table 2). Predominant drugs administered for COVID-19 management included glucocorticoids (51%) and anticoagulants (20%). Most patients were managed as outpatients following COVID-19 diagnosis. Nevertheless, a noteworthy proportion experienced severe adverse outcomes (Table 3). Acute respiratory distress syndrome developed in 38 individuals (36%), and nine patients (8%) ultimately succumbed to the disease. A composite outcome, encompassing major adverse events, was recorded in 45 patients (43%). The incidence of major adverse events was similar across different SARDs, although mortality was more frequent in patients with SLE (20%) or antiphospholipid syndrome (27%) compared to other conditions (p=0.013). Among the deceased, five patients had SLE (two of whom also had antiphospholipid syndrome, and one additional patient overlapping with RA), two had RA, one had systemic vasculitis, and one had primary antiphospholipid syndrome.

Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its treatment.

| Total (n=103) | |

|---|---|

| Disease severity at presentation | |

| Mild-to-moderate | 74 (71) |

| Severe or critical | 29 (28) |

| Symptomatic disease | |

| Respiratory | 81 (78) |

| Fever | 65 (63) |

| Headache | 62 (60) |

| Musculoskeletal | 30 (29) |

| Anosmia | 23 (22) |

| Gastrointestinal | 22 (21) |

| Neurologic | 3 (2) |

| COVID-19 medications (new indication) | |

| Glucocorticoids | 53 (51) |

| Anticoagulants | 21 (20) |

| Antimalarials | 19 (18) |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 13 (12) |

| Ivermectin | 9 (8) |

| Jak/STAT inhibitors | 2 (1) |

| Tocilizumab | 1 (1) |

| Remdesivir | 1 (1) |

Data are presented as n (%).

COVID-19-associated adverse outcomes according to the most common rheumatic diseases.

| Total events | RA(n=61) | SLE(n=25) | SSc(n=20) | SS(n=9) | APS(n=11) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 38 | 27 (44) | 8 (32) | 6 (30) | 2 (22) | 6 (54) | 0.393 |

| Superimposed bacterial infection | 3 | 1 (1) | 2 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (9) | 0.334 |

| Thrombosis | 4 | 0 | 2 (8) | 0 | 1 (11) | 1 (9) | 0.105 |

| Death | 9 | 3 (4) | 5 (20) | 0 | 0 | 3 (27) | 0.013 |

| Composite outcome | 45 | 28 (45) | 11 (44) | 7 (35) | 4 (44) | 6 (54) | 0.872 |

Data are presented as n (%). Significant p value is in bold.

APS, antiphospholipid syndrome; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SS, Sjögren's syndrome; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

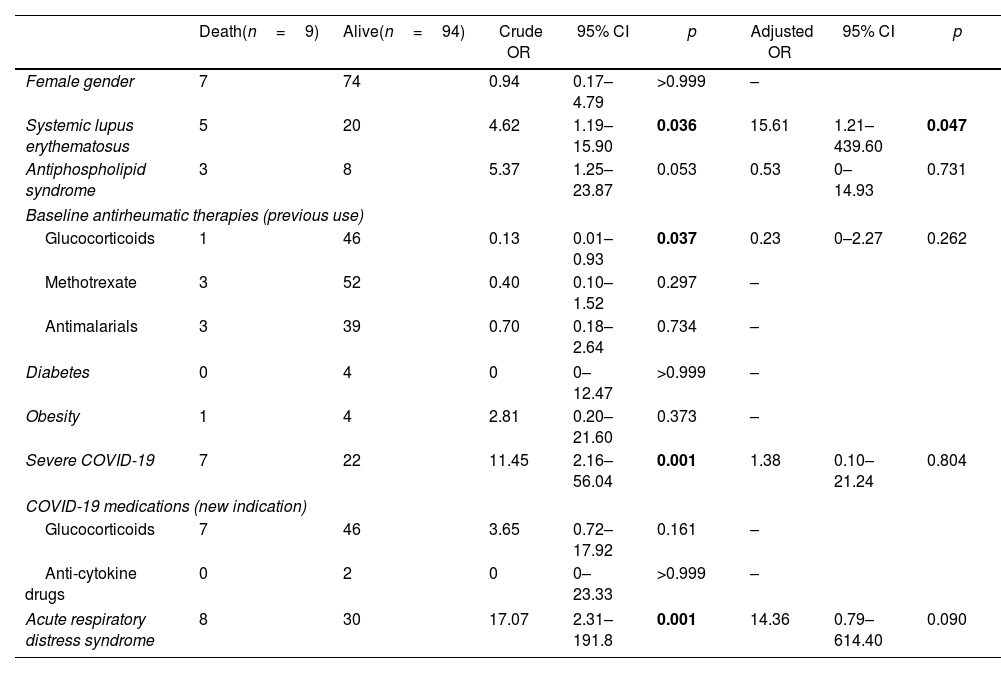

Analysis of mortality predictors is presented in Table 4. The findings revealed that underlying SLE (OR 4.62, 95% CI 1.19–15.90; p=0.036), severe COVID-19 at admission (OR 11.45, 95% CI 2.16–56.04; p=0.001), and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome during follow-up (OR 17.07, 95% CI 2.31–191.80; p=0.001) were significantly associated with mortality. Conversely, baseline use of glucocorticoids for antirheumatic therapy was associated with a decreased mortality risk (OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.01–0.93; p=0.037). Following adjustment for confounding factors, SLE emerged as the sole significant predictor of mortality (adjusted OR 15.61, 95% CI 1.21–439.60; p=0.047).

Crude and adjusted predictors of mortality.

| Death(n=9) | Alive(n=94) | Crude OR | 95% CI | p | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 7 | 74 | 0.94 | 0.17–4.79 | >0.999 | – | ||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 5 | 20 | 4.62 | 1.19–15.90 | 0.036 | 15.61 | 1.21–439.60 | 0.047 |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | 3 | 8 | 5.37 | 1.25–23.87 | 0.053 | 0.53 | 0–14.93 | 0.731 |

| Baseline antirheumatic therapies (previous use) | ||||||||

| Glucocorticoids | 1 | 46 | 0.13 | 0.01–0.93 | 0.037 | 0.23 | 0–2.27 | 0.262 |

| Methotrexate | 3 | 52 | 0.40 | 0.10–1.52 | 0.297 | – | ||

| Antimalarials | 3 | 39 | 0.70 | 0.18–2.64 | 0.734 | – | ||

| Diabetes | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0–12.47 | >0.999 | – | ||

| Obesity | 1 | 4 | 2.81 | 0.20–21.60 | 0.373 | – | ||

| Severe COVID-19 | 7 | 22 | 11.45 | 2.16–56.04 | 0.001 | 1.38 | 0.10–21.24 | 0.804 |

| COVID-19 medications (new indication) | ||||||||

| Glucocorticoids | 7 | 46 | 3.65 | 0.72–17.92 | 0.161 | – | ||

| Anti-cytokine drugs | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0–23.33 | >0.999 | – | ||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 8 | 30 | 17.07 | 2.31–191.8 | 0.001 | 14.36 | 0.79–614.40 | 0.090 |

This study sought to investigate risk factors associated with adverse outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with SARDs in Ecuador and Mexico. The results of this study shed light on the substantial severity and elevated risk of complications and mortality faced by these patients, with SLE emerging as a significant independent predictor of death.

Consistent with existing literature, our findings underscored a higher prevalence of SARDs among females, reflected in the predominantly female composition of our patient sample (78%). A similar pattern was reported by the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance, which encompassed 10,117 SARD patients with COVID-19 and revealed that 76.7% were women.16 While this female predominance might initially suggest a less severe clinical course, our study's context in Latin America introduced complexities. Earlier research has demonstrated that SARD patients in this region experience higher self-assessed disease activity, reduced medication adherence, and challenges in medical follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic. These factors potentially counteract the protective effect of female sex observed in our cohort and contribute to poorer prognostic indicators.17

The type of underlying autoimmune disease also appeared to play a significant role. Notably, RA and SLE consistently emerged as the most prevalent SARDs in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.17–20 The COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance found that 40.9% of the patients had RA as the primary rheumatic disease, while SLE accounted for 17.7%.16 However, our registry highlighted significantly higher frequencies of both diseases, with RA and SLE accounting for 59% and 24% of cases, respectively. This observation is noteworthy due to evidence from Europe and the United States indicating that RA patients exhibit heightened susceptibility to severe COVID-19, necessitating hospitalization and carrying an elevated risk of mortality compared to the general population.21,22 A study from Brazil also revealed that RA patients with comorbid heart disease and glucocorticoid use have a higher likelihood of hospital admission due to COVID-19.13 Similarly, SLE patients have an increased risk of developing COVID-19-associated organ failure, with nearly double the risk of mortality in comparison to others.23 A Brazilian study demonstrated that SLE patients hospitalized for COVID-19 have significantly higher risks of death and poor outcomes compared to patients with other comorbidities.24 Another study conducted in Argentina, where the majority of SLE patients had mild COVID-19, reported a mortality rate close to 3%, with antiphospholipid syndrome, hypertension, and high-dose glucocorticoid use being predictors of severity and death.25 However, other studies have reported comparable mortality rates between SLE patients and the general population, although with higher risks of hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, thromboembolism, and admission to the intensive care unit.26,27 Notably, our registry's overrepresentation of RA and SLE patients could contribute to the observed higher mortality and risk of complications in our study.

The disproportionately high rates of complications and mortality associated with COVID-19 in Latin America, a region characterized by environmental, social, and governance challenges, extended to our SARD patient cohort, where the rates reached 43% and 8%, respectively. These findings align with broader patterns of elevated COVID-19-related mortality across several Latin American countries.16,19 Environmental factors such as air pollution, population mobility, and low human development indices, combined with social inequities and limited healthcare access, likely contribute to these disparities. In comparison, a study from Oman reported a lower 30-day mortality rate (3.5%) among SARD patients with COVID-19, emphasizing factors such as diabetes, obesity, and organ damage.28 A study from Argentina described a 4% mortality rate among patients with rheumatic conditions, with underlying vasculitis as the sole factor associated with increased mortality. It is worth noting that this study included patients with osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia, while autoimmune diseases associated with highest mortality (RA and SLE) were underrepresented.14

Sub-analyses have highlighted ethnic disparities even within high-income countries. For instance, Latino patients in the United States demonstrated twofold and threefold increased risks of hospitalization and ventilatory support, respectively, compared to White patients.12 This demographic also exhibited a 7% mortality rate, reflecting the influence of socioeconomic inequities on healthcare access. Ethnicity-based genetic factors may also play a role, as evidenced by varying mortality rates among different ethnic groups.12,29 SARD patients of Asian descent in the United States experience nearly twice the mortality rate compared to those of Caucasian or African American descent when infected with SARS-CoV-2, with Latinos exhibiting intermediate mortality rates.12,29

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Firstly, the inclusion of patients in the registry was based on the discretion of participating rheumatologists, which introduces a selection bias and does not capture all cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection among SARD patients. Secondly, the medical facilities involved may not be representative of the entire Latin American region. Thirdly, various clinical, demographic, and sociocultural variables could not be reliably assessed. Fourthly, our findings are valid only for the SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating during the study period. Finally, we were unable to assess the impact of anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Despite these limitations, our study contributes to the understanding of SARD patients’ clinical course with COVID-19 in Latin American nations. While not definitive in identifying high-risk patients during the pandemic's current phase, our study underscores the urgency of addressing healthcare disparities. As countries unprepared to handle catastrophic diseases like COVID-19 encounter patients burdened by debilitating conditions, intervention efforts aimed at mitigating disparities hold the potential to improve outcomes among vulnerable populations.

ConclusionsIn the context of SARD patients in Ecuador and Mexico, our findings underscore a profound susceptibility to severe complications and mortality upon SARS-CoV-2 infection. The study pinpointed SLE, severe COVID-19 at admission, and the occurrence of acute respiratory distress syndrome as pivotal factors significantly heightening the risk of mortality. These insights illuminate the critical need for tailored medical interventions and heightened vigilance for this vulnerable patient population in the ongoing battle against the pandemic.

Financial supportThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestNone.

None.