Adjuvant-induced autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome (ASIA) comprises a spectrum of clinical manifestations associated with exposure to diverse adjuvants that have in common the generation of non-specific autoantibodies and loss of immune tolerance.

ObjectiveThis study aimed to develop a narrative review of the literature about the pathogenesis underlying ASIA syndrome, its differentiation from other defined autoimmune diseases, and prospects for future research in this field.

Materials and methodsA narrative review of the literature was conducted using Pubmed, Embase, and LILACS. All publications on the subject were included, with no time limit in English and Spanish. Finally, 25 articles published since 1990 were included, from which we reviewed the pathogenesis, diagnostic criteria, and its differentiation from other defined autoimmune processes.

ResultsThe appearance of ASIA syndrome seems to be linked to an individual’s genetic predisposition (HLA-DRB1*01 or HLA-DRB4) and is the result of the interaction of external and endogenous factors that trigger autoimmune phenomena. In recent years, physicians have become more aware of the relationship between exposure to adjuvants and the development of underlying signs and symptoms that may correspond to ASIA syndrome. The current evidence supporting its existence is still contradictory. A timely diagnosis requires a multidisciplinary approach and could require immunosuppressive treatment in particular cases.

ConclusionsIn recent years a relationship between exposure to adjuvants and the appearance of autoimmunity phenomena has been recognized. In clinical practice, physicians can find cases of ASIA syndrome. However, the evidence is still debated on the relationship between adjuvants and autoimmune clinical manifestations. ASIA syndrome classification criteria require validation in various populations before being applied to select patients for clinical studies. It is necessary to identify the risk factors for ASIA syndrome to understand its pathophysiology and make a timely diagnosis.

El síndrome autoinmune/inflamatorio inducido por adyuvantes (ASIA) comprende un espectro de manifestaciones clínicas asociadas con la exposición a distintos adyuvantes, los cuales tienen en común la generación de autoanticuerpos no específicos a partir de la pérdida de tolerancia inmune.

ObjetivoEl objetivo del estudio fue llevar a cabo una revisión narrativa de la literatura sobre la patogénesis que subyace al sindrome ASIA, su diferenciación de otros procesos autoinmunes definidos y las perspectivas de la investigación futura en este campo.

Materiales y métodosSe hizo una revisión narrativa de la literatura en Pubmed, Embase y LILACS, se incluyeron todo tipo de publicaciones en el tema, sin límite de tiempo, en inglés y español. Finalmente, se incluyen 25 artículos publicados desde 1990, a partir de los cuales se revisa la patogénesis, los criterios diagnósticos y su diferenciación de otros procesos autoinmunes definidos.

ResultadosLa aparición del síndrome ASIA parece estar vinculada a una predisposición genetica individual (HLA-DRB1*01 o HLA-DRB4) y es el resultado de la interacción de factores externos y endógenos que desencadenan fenómenos de autoinmunidad. En los últimos años, los médicos son más conscientes de la relación entre la exposición a los adyuvantes y el desarrollo de síntomas larvados en el tiempo que pueden corresponder a un sindrome ASIA. La evidencia actual que apoya su existencia aun es controversial. El diagnóstico oportuno requiere un enfoque multidisciplinario y podría hacer necesario un tratamiento inmunosupresor en casos particulares.

ConclusionesLa exposición a adyuvantes y su relación con la aparición de fenómenos de autoinmunidad ha sido reconocida en los ultimos años. En la práctica clínica pueden encontrarse casos de síndrome ASIA, a pesar de que la evidencia que sustenta la relación entre adyuvantes y manifestaciones clínicas autoinmunes aún es debatida. Los criterios clasificatorios de síndrome ASIA requieren validación en diversas poblaciones, antes de ser aplicados en la selección de pacientes para estudios clínicos. Es necesario identificar factores de riesgo para síndrome ASIA, con el fin de comprender mejor la fisiopatología y hacer un diagnóstico oportuno.

In 1964, Miyoshi et al. reported for the first time the potential complications of treatment with silicone and paraffin fillers, categorized as human adjuvant disease (HAD). From 2008 to 2012, Alijotas-Reig et al. identified a series of cases termed “human adjuvant-like disease,” encompassing manifestations triggered by synthetic bioimplants other than silicone and paraffin.1,2

In 2011, Shoenfeld and Agmon-Levin coined the term adjuvant-induced autoimmune/autoinflammatory syndrome (ASIA) to describe specific clinical manifestations resulting from an immune response to adjuvants. These conditions manifest with variable latency periods (from 3 weeks to several years), influenced by genetic and environmental factors in certain predisposed populations.3

ASIA syndrome comprises a spectrum of symptoms and signs observed in individuals exposed to adjuvants (substances capable of increasing the immunogenicity of an antigen without awakening an immune response per se), found in vaccine excipients (e.g., aluminum hydroxide or phosphate salts), prostheses (e.g., breast, buttock, or facial fillers), and even medical devices (e.g., pacemakers). Theoretically, these adjuvants can induce loss of tolerance and dysregulation of humoral and cellular immunity against self-antigens, particularly in individuals with genetic predispositions, such as higher prevalence of certain alleles (e.g., HLA-DQ2 and DRW53).3,4

ASIA syndrome generally groups four entities: macrophagic myofasciitis syndrome, Gulf War syndrome, siliconosis, and specific post-vaccine phenomena associated with aluminum hydroxide adjuvants (e.g., vaccines against HPV and influenza). Some authors have proposed adding a fifth entity, sick building syndrome, characterized by nonspecific respiratory symptoms likely linked to heightened sensitivity to environmental pollutants, though its inclusion remains debated.3,4 Therefore, given its primarily self-reported symptom basis, sick building syndrome is excluded from this review.

Diagnosis of ASIA syndrome is primarily exclusionary. Comprehensive medical history and personal background are crucial, alongside the identification of specific antibodies associated with the syndrome (e.g., anti squalene antibodies). Additionally, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has proven valuable in detecting distant silicone deposits and documenting granulomas in subcutaneous tissue and muscles.5

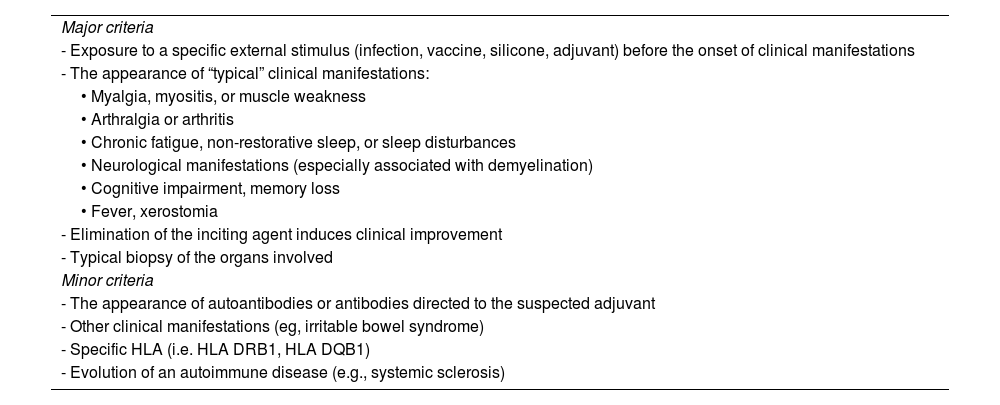

In 2011, Shoenfeld and Agmon-Levin proposed 12 clinical criteria for ASIA syndrome diagnosis. Meeting either two major criteria or one major and two minor criteria is sufficient for classification. However, these criteria lack specificity, some of their components are not sufficiently defined and may lead to the misclassification of various autoimmune diseases like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis as ASIA syndrome. Recently, Alijotas-Reig proposed new classification criteria, but both sets await validation.6

This narrative review explores the literature on ASIA syndrome, encompassing its pathophysiological foundations, clinical characteristics, and diagnostic approaches to aid in the timely recognition of suspicious cases in clinical practice in healthcare personnel.

AimTo conduct a narrative review of the literature on the pathogenesis underlying ASIA syndrome, distinguish it from other defined autoimmune processes, and outline future research prospects in this field.

MethodsLiterature searchA bibliographic search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, and LILACS databases using the MeSH terms “ASIA syndrome,” “Silicone,” and “Review” between January and April 2022.

There was no time limit for publications, as many studies are retrospective cohorts analyzed over time, and diagnostic criteria for ASIA syndrome have evolved.

PopulationStudies including subjects over 18 who met the diagnostic criteria for ASIA syndrome, as reported in the literature, were eligible for inclusion.

Inclusion criteriaAll types of publications on the topic were considered, including case reports, clinical trials, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, letters to the editor, and editorials. Only studies in English were included, yielding 62 initial results.

Selection of studiesInitially, comprehensive reviews were prioritized, resulting in the final selection of 25 articles published since 1990 based on their relevance, objectivity, and content significance.

ResultsDefinitionASIA comprises a set of clinical symptoms and signs that appear with a variable latency time after exposure to adjuvants such as aluminum, squalene, pristane, or silicone. These symptoms may or may not meet defined classification criteria for immune-mediated diseases such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory myopathies, systemic sclerosis, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, and even fibromyalgia.3,4

Macrophagic myofasciitis syndrome involves the infiltration of macrophages and CD8+ T cells loaded with aluminum nanoparticles into fascia and skeletal striated muscle, without muscle fiber necrosis/damage or deposit of complement system proteins. It has been associated with vaccines (e.g., against hepatitis B virus) containing aluminum hydroxide. The syndrome is closely linked to polymorphisms in the major histocompatibility complex HLA-DRB1*01.4,6

Gulf War Syndrome is characterized by chronic fatigue and sleep disorders linked to exposure to squalene, and possibly aluminum hydroxide, in individuals vaccinated against anthrax. It resembles fibromyalgia but its association with anti-squalene antibodies suggests an imbalance in the regulation of T helper type 2 (Th2) cells.4

Siliconosis or silicone implant incompatibility syndrome presents similarly to the aforementioned conditions. The abnormal immune response (both clinically and circulating autoantibodies) induced by silicone may diminish following removal of the implanted material.3

Case reports and series have described post-vaccination phenomena reminiscent of autoimmune-related symptoms, such as arthralgias, myalgias, fatigue, and general malaise, in patients vaccinated against HPV and influenza, associated with aluminum hydroxide and phosphate adjuvants. Some patients with pre-existing autoimmune disease may experience symptom reactivation following vaccination. However, current evidence on the safety and efficacy of vaccines does not support a consistent association with the development of autoimmune phenomena. Identifying population risk factors and conducting long-term clinical follow-up (post-marketing and pragmatic studies) will be crucial in defining the risk/benefit balance of vaccination in adults. Presently, the undeniable benefit of vaccination in preventing infectious diseases and their complications outweighs the minimal risk of serious post-vaccine phenomena. A definitive cause-effect relationship between vaccination and the onset of ASIA syndrome has not been consistently established.3

EpidemiologySince 2011 and to date, more than 4479 cases of ASIA syndrome have been reported. Approximately 92.7% of these occurred in women and were primarily associated with adjuvants found in vaccines against human papillomavirus and hepatitis B. In this systematic review, severe cases accounted for 6.8% with a mortality rate of 0.24%.7 The prevalence ranges widely from 0.5% to 25.7%, with clinical presentations often resembling polygenic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus; autoinflammatory conditions are less common (0.5%–2.5%).7 Currently, there is no available data regarding the frequency and associated risk factors specific to ASIA syndrome in our context. The relationship between adjuvants and the onset of autoimmune phenomena remains contentious; however, some observational studies have suggested a potential association.8,9

In 1996, a retrospective cohort study compared 10,830 women with silicone breast implants to unexposed women and found a statistically significant relative risk (RR) of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.08–1.41; P = .0015) for developing any connective tissue disease, particularly undifferentiated/mixed connective tissue disease. This study was deemed high-risk for bias due to its reliance on self-reported connective tissue disease outcomes. No significant increase in the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus or other immune-mediated diseases was observed, and the RR did not reach statistical significance.8

In a case-control study, Watad et al. demonstrated an association between silicone implants and the development of autoimmune diseases, reporting an odds ratio (OR) of 1.22 (95% CI: 1.18–1.26). The strongest associations were observed for sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, and systemic sclerosis.9

Conversely, Gabriel et al., in a study of the Olmsted County cohort (Minnesota, USA), found no increased risk of connective tissue diseases among women with breast implants (RR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.34–2.97).10 In 1995, Sánchez-Guerrero et al. published results from a retrospective cohort of 1183 women with silicone breast implants followed from 1976 to 1990 in the New England Journal of Medicine. The age-adjusted RR was 0.6 (95% CI: 0.2–2.0), which was not statistically significant. This study used standardized criteria for diagnosing autoimmune diseases rather than relying on self-reported symptoms.11

In 2000, Janowsky et al. conducted a meta-analysis concluding that silicone breast implants could be considered safe. However, this meta-analysis excluded the Hennekens et al. study due to its reliance on self-reported symptoms; had it been included, the relative risk for developing connective tissue disease would have reached statistical significance, with an RR of 1.3.8,13

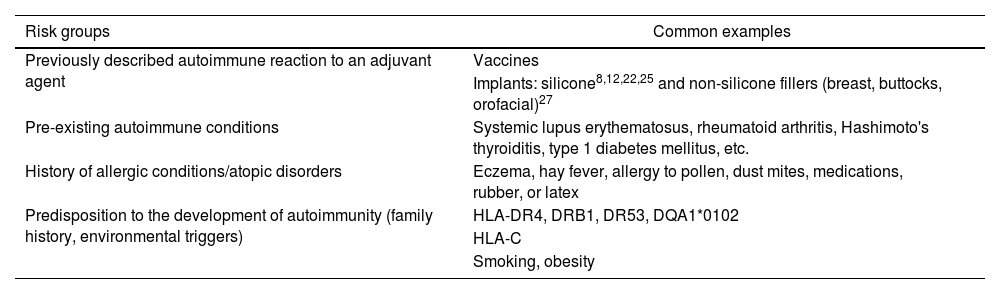

In summary, the relationship between ASIA syndrome and implant exposure remains controversial. Studies indicating an association often carry a high risk of bias, primarily due to self-reporting of symptoms and insufficient long-term follow-up. The development of autoimmune diseases appears to be a rare event and likely not directly linked to implants; however, pathophysiological perspectives suggest that certain symptoms may manifest following exposure to adjuvants. Table 1 outlines risk factors associated with a higher frequency of ASIA syndrome.14

Risk factors associated with silicone implant incompatibility syndrome or siliconosis.

| Risk groups | Common examples |

|---|---|

| Previously described autoimmune reaction to an adjuvant agent | Vaccines |

| Implants: silicone8,12,22,25 and non-silicone fillers (breast, buttocks, orofacial)27 | |

| Pre-existing autoimmune conditions | Systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, etc. |

| History of allergic conditions/atopic disorders | Eczema, hay fever, allergy to pollen, dust mites, medications, rubber, or latex |

| Predisposition to the development of autoimmunity (family history, environmental triggers) | HLA-DR4, DRB1, DR53, DQA1*0102 |

| HLA-C | |

| Smoking, obesity |

Source: Taken from Soriano et al.13

Adjuvants are substances that enhance the immune response to antigens but cannot initiate this response on their own. They consist mostly of exogenous substances intentionally administered (e.g., aluminum hydroxide in vaccines) or unintentionally introduced (e.g., plasticizers).

These substances can induce gradual antigen release, hinder its clearance, or prolong exposure to antigen-presenting cells (APCs).15 Additionally, infectious agents or their derivatives can act as adjuvants. For instance, autoimmune lymphocytic thyroiditis can be induced in animal models injected with thyroglobulin plus complete Freund's adjuvant. Edelman proposes a classification of adjuvants based on their immunological mechanisms4,15:

- -

Boosters of immune response against associated antigens (innate and adaptive immunity).

- -

Vehicles facilitating antigen-receptor interaction in innate and adaptive immune cells.

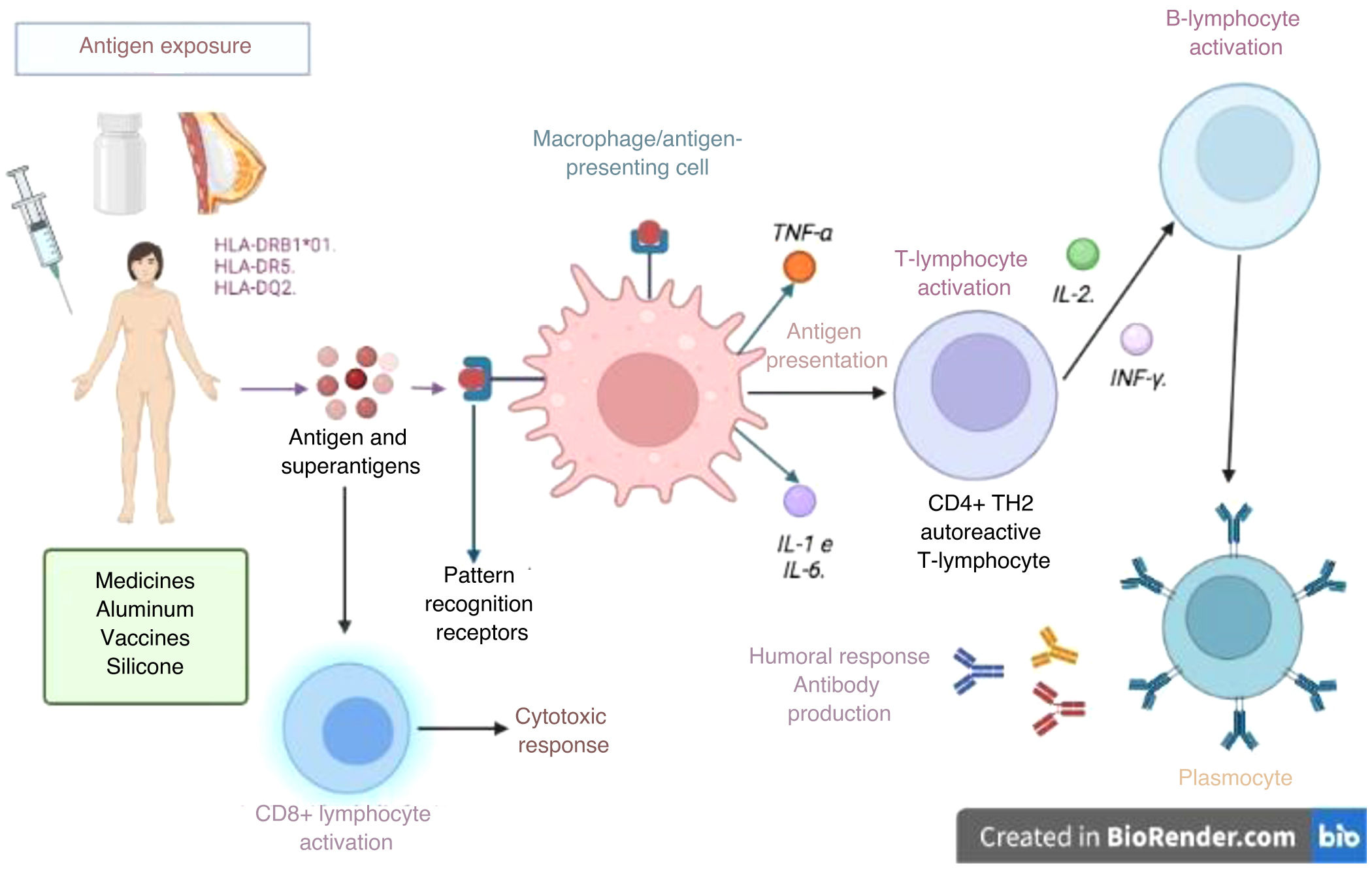

Adjuvants augment innate immune response by mimicking evolutionarily conserved molecules like bacterial walls or unmethylated CpG-DNA residues, binding to Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on APCs.16 This innate response activates NLRP3 inflammasomes or directly activates macrophages (or other phagocytic cells like neutrophils), natural killer (NK) lymphocytes, or innate lymphoid cells through various receptors (TLRs, NOD-like receptors, and C-type lectins). Moreover, adjuvants enhance adaptive response by promoting dendritic cell interaction with T cells and increasing antigen uptake by APCs (Fig. 1).

Activation of the immune response in ASIA syndrome. When an individual with certain HLA type 1 or 2 alleles (i.e., HLA-DRB1*01, HLA-DR5, and HLA DQ2) is exposed to adjuvants, an abnormal interaction on antigen-presenting cells and macrophages is enabled. These cells produce cytokines that lead to a loss of immunological tolerance, which induces humoral (B-lymphocytes and plasma cells that produce autoantibodies) or cellular (with activation of CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes) immune responses, which perpetuates the inflammatory process, with subsequent endothelial dysfunction, persistent inflammation, and secondary tissue damage.

Source: Own elaboration.

The locus in the genome encoding major histocompatibility complexes (MHC), known as the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, is critically important. HLA encodes proteins crucial for antigen presentation and plays a vital role in pathogen recognition and autoimmunity. HLA coding is highly diverse among individuals and populations. HLA polymorphisms, particularly HLA-DRB1, account for both the rarity and increased susceptibility of certain individuals to autoimmune diseases and adverse reactions to adjuvants. Three HLA class I and II haplotypes (HLA DR2DQ6, DR4DQ8, and DR3DQ2) are associated with most autoimmune diseases.17,18

Autoimmune diseases are categorized into distinct clusters but share a common genetic and environmental background. External environmental factors such as infectious agents, adjuvants, silicone, and aluminum salts must converge to trigger disease in genetically susceptible individuals.5

Interestingly, conditions like sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, undifferentiated connective tissue disease, and silicone implant incompatibility syndrome share pathogenic aspects, explaining the potential for overlap syndromes over time.7

Pathogenic role of silicone in ASIA syndromeSilicone is a group of synthetic polymers containing alternating silicone and oxygen atoms, with various physical forms such as liquid, resins, and elastomers, determined by the degree of polymerized siloxanes.14 In cases of silicone implant incompatibility syndrome, it has been proposed that measuring IgG antibodies against G protein-coupled adrenergic and muscarinic receptors could serve as an early marker of autoimmunity. These antibodies precede the appearance of conventional autoantibodies (e.g., antinuclear antibodies [ANA], extractable nuclear antigen [ENA], anti-DNA, and anti-cardiolipin IgM and IgG). Furthermore, such antibodies directly contribute to the damage of small nerve fibers associated with chronic fatigue, muscle weakness, and nonspecific autonomic gastrointestinal symptoms.19–21

Individuals with siliconosis may develop periprosthetic capsular material as part of an inflammatory response to a foreign body, consisting of fibrotic capsular tissue containing myofibroblasts, CD4+ lymphocytes, macrophages, and adjacent multinucleated giant cells—a condition known as siliconoma.15,22 However, not all these cases progress to ASIA syndrome.

In vitro studies have indicated that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from individuals experiencing late-onset inflammatory reactions after silicone injections exhibit higher baseline levels of interleukin-6 and TNF-α compared to PBMCs from healthy individuals. These subjects did not show the presence of memory CD4+ T cells against silicone, as indicated by the absence of CD69 expression and IFN-γ or IL-2 production. This suggests that silicone might induce inflammatory responses through an adjuvant mechanism rather than as an antigen.22

Cuellar et al. analyzed 813 individuals with silicone breast implants for ANA detection using a HEp-2 cell line. They found an unusually high ANA positivity rate (57.8%). Notably, nucleolar and anticentromere immunofluorescence patterns typically observed in diffuse and limited systemic sclerosis were present in 13.4% and 1.06% of patients, respectively.23

In conclusion, most hypotheses suggest that exposure to silicone initially leads to alterations in innate immunity in genetically susceptible individuals. This is followed by loss of tolerance and the generation of self-reactive T and B lymphocyte populations, resulting in granulomatous foreign body reactions and cytokine responses associated with various systemic manifestations.24

DiagnosisASIA syndrome requires a history of adjuvant exposure for diagnosis. Associations between adjuvants in vaccines and ASIA syndrome-compatible manifestations are documented in case reports and series:

- •

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) following influenza or adenoviral vector COVID-19 vaccines, though the risk is minimal. This association remains controversial and insignificant compared to GBS risk post-natural infection or in the unvaccinated.

- •

Transverse myelitis post-oral polio vaccine.

- •

Arthritis post-Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis (DPaT) and Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccinations.

- •

Autoimmune thrombocytopenia post-MMR vaccine.

- •

From 2011 to 2016, over 4000 ASIA syndrome cases were reported, with vaccines (especially HPV and influenza), silicone implants, and mineral oil fillings being most frequently implicated.7

Clinical manifestations include non-specific symptoms (myalgia, arthralgia, fever, fatigue, insomnia) and those resembling autoimmune diseases (sicca symptoms, malar rash, oral ulcers, lymphadenopathy, serositis, arthritis, myositis, Raynaud's phenomenon, purpura, livedo reticularis, demyelinating phenomena, or axonal damage). Fatigue predominates and may persist even after implant removal. Arthralgias affect 90% of patients and are typically mechanical, unlike inflammatory joint involvement in diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus.

Myalgias often mimic inflammatory myopathy distribution, predominantly proximal in 90% of cases. Regarding specific manifestations of autoimmunity, sicca symptoms (xerophthalmia, xerostomia) occur in 75%, and Raynaud's phenomenon in 30%–50%.25

Macrophagic myofasciitis syndrome presents with fatigue, asthenia, myalgia, arthralgia, muscle weakness, cognitive alterations, and insomnia. Severe conditions like inflammatory myopathies and Guillain-Barre-like demyelinating polyneuropathy can also occur. Post-vaccine syndromes typically present milder symptoms, including fever, gastrointestinal, and respiratory issues.

Gulf War Syndrome manifests with fatigue, sleep disturbances, myalgia, and muscle weakness, akin to fibromyalgia (a central pain amplification syndrome). Up to 95%–100% of cases have anti squalene antibodies.

Siliconosis resembles nonspecific symptoms described in macrophagic myofasciitis syndrome but with higher rates of cognitive and neurological disorders (headache, paresthesias, depression), described in 30%–60% of cases. This syndrome may occur with intact or ruptured implants and can involve various autoantibodies. The onset period varies widely, from 6 to 70 months post-implant. Local inflammatory signs (edema, heat, erythema, and pain at the site of implantation of the prosthetic material) often precede systemic symptoms. Presentation as autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, systemic sclerosis, Sjögren syndrome, mixed connective tissue disease, inflammatory myopathies, sarcoidosis, vasculitis) manifest in 11% of cases following implants.1,25

Despite half a century of global silicone implant use, their biological safety remains debated. In 1992, the FDA restricted silicone breast implant use in the US due to reported fibromyalgia-like conditions and autoimmunity. ASIA syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring ruling out infectious or autoimmune causes of symptoms. Table 2 outlines diagnostic criteria proposed by Shoenfield et al., modified by Alijotas-Reig in 2015; their specificity is debated.2,3

Suggested criteria for the diagnosis of ASIA syndrome.

| Major criteria |

| - Exposure to a specific external stimulus (infection, vaccine, silicone, adjuvant) before the onset of clinical manifestations |

| - The appearance of “typical” clinical manifestations: |

| • Myalgia, myositis, or muscle weakness |

| • Arthralgia or arthritis |

| • Chronic fatigue, non-restorative sleep, or sleep disturbances |

| • Neurological manifestations (especially associated with demyelination) |

| • Cognitive impairment, memory loss |

| • Fever, xerostomia |

| - Elimination of the inciting agent induces clinical improvement |

| - Typical biopsy of the organs involved |

| Minor criteria |

| - The appearance of autoantibodies or antibodies directed to the suspected adjuvant |

| - Other clinical manifestations (eg, irritable bowel syndrome) |

| - Specific HLA (i.e. HLA DRB1, HLA DQB1) |

| - Evolution of an autoimmune disease (e.g., systemic sclerosis) |

ASIA: Adjuvant-induced autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome; HLA: Human Leukocyte Antigens.

Source: Taken from Watad et al.4

Elevation of acute-phase reactants and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia are common initial findings in ASIA syndrome, typically observed within the first days or months of the disease. Anemia of chronic disease appears later in its course. It is crucial to include specific paraclinical tests in the differential diagnosis:

- -

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): Primary hypothyroidism can present with fatigue, myalgia, and symptoms resembling inflammatory myopathy.

- -

Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D: Deficiency exacerbates symptoms in ASIA syndrome and can mimic inflammatory myopathy.

- -

Muscle enzymes: Total creatine phosphokinase, lactate dehydrogenase, and transaminases (AST, ALT) help diagnose immune-mediated myopathies.

Autoantibody studies, while not specific, often show positive ANA in 15%–30% of patients. These tests should be interpreted in the clinical context, as up to 10% of individuals with ASIA syndrome meet criteria for specific immune-mediated diseases.25,26

Given common sicca symptoms and Raynaud's phenomenon, it is essential to rule out primary Sjögren syndrome or systemic sclerosis with minor salivary gland biopsy and capillaroscopy, respectively. For patients presenting with myalgia and proximal muscle weakness, MRI is recommended to detect myositis and muscle edema indicative of inflammatory myopathy. When MRI is unavailable, electromyography with neuroconduction velocities may be useful to search for a suggestive myopathic pattern.25

Diagnostic imaging, particularly MRI, is indispensable for evaluating implant integrity, associated inflammatory changes, rupture, collections, and distant material dissemination. It also helps determine the surgical approach for implant removal. Patients with ASIA syndrome may exhibit calcifications and granulomatous nodules around implants; suspicion of implant rupture (indicated by pain or adjacent inflammatory changes) requires prompt MRI to aid diagnosis and guide management.15

TreatmentDespite the absence of well-designed studies and evidence-based management guidelines demonstrating the positive effects of certain drugs on local inflammatory disorders such as panniculitis related to bioimplants, their efficacy has been reported in case reports and series. Besides specific pharmacological interventions, smoking cessation is advised, along with correction of vitamin D deficiency, particularly in patients experiencing fatigue, arthralgia, and myalgia.27

Systemic corticosteroids remain the cornerstone of treatment for acute and delayed immune-mediated adverse reactions to fillers. Medium-high doses of prednisone (0.5–1 mg/kg/day) have consistently shown effectiveness, with no refractory cases reported to date.28,29

Given the chronic nature of these pathological reactions, patients may develop criteria for corticosteroid dependence. Therefore, steroid-sparing agents like antimalarials, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and occasionally azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and minocycline have been proposed. Alijotas-Reig et al. (unpublished results) demonstrated in an in vitro model using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from individuals with granulomatous and autoimmune lesions related to silicone, hyaluronic acid, and acrylamides that all these drugs can inhibit various proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL1-β, IL-2, and IL-6 to varying degrees.30,31

Most registries published to date indicate an acceptable clinical response in over 70% of cases treated over 2 years. Treatment often requires combinations of glucocorticoids and immunomodulatory drugs, with tacrolimus being one of the most extensively studied.32 Tacrolimus inhibits IL-2 production and T-cell proliferation. In a retrospective analysis involving clinical, biochemical, and histopathological data from 45 subjects diagnosed with late-onset ASIA syndrome related to bioimplants (occurring 3 months or more after the procedure), practically all cases refractory to other immunosuppressants responded to tacrolimus, generally at low doses. High doses were necessary in only 20% of treated patients, with no significant clinical or biological adverse effects observed.1,32

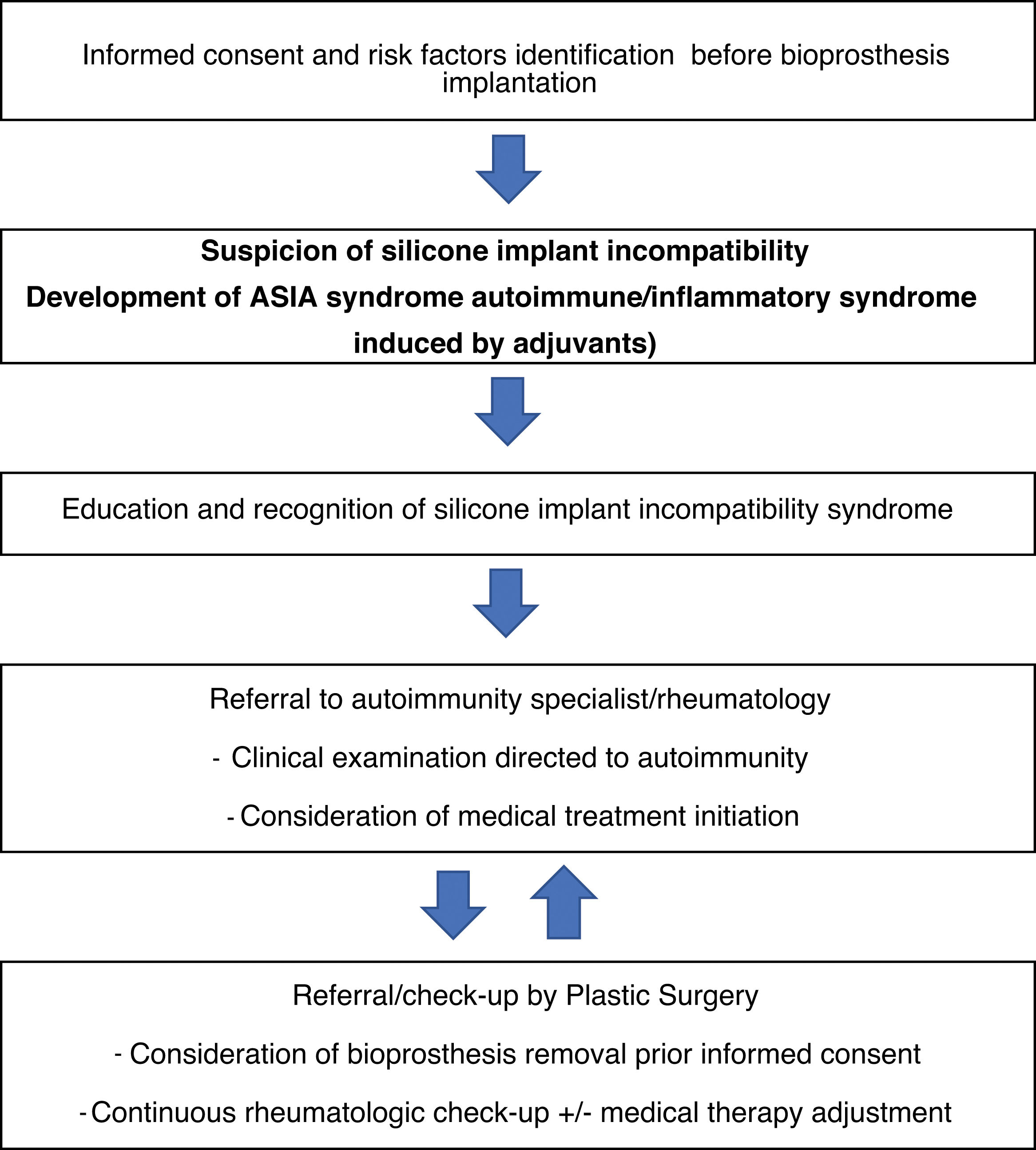

The role of implant removal is debated; however, withdrawal is recommended in systemic, severe, or refractory cases, resulting in objective clinical improvement in approximately 50% of cases. For instance, Maijers et al. described a cohort of 80 women, of whom 52 opted for silicone prosthesis explantation; among these, 27 experienced partial symptom improvement, and 9 achieved complete resolution.33,34 Lastly, a management algorithm for siliconosis is proposed (Fig. 2).

Management proposal for patients with silicone implant incompatibility syndrome or siliconosis.

Source: Taken from Shoenfeld and Agmon-Levin.3

There is evidence supporting a relationship between exposure to adjuvants and symptoms related to autoimmunity/autoinflammation, as demonstrated by experimental (animal studies), descriptive (case reports and series), and observational (case-control studies) models. However, cohort studies with appropriate design and long-term follow-up do not consistently support this association. Nonetheless, clinical cases of ASIA syndrome linked with substances such as silicone, mineral oils, squalene, and aluminum hydroxide are observed in practice.

Validating the proposed classification criteria for ASIA syndrome remains a priority to ensure the inclusion of more homogeneous study populations. Clinical suspicion and exposure history remain crucial for diagnosis.

Large-scale studies with well-defined inclusion criteria, reproducible outcomes, and long-term follow-up are necessary to identify modifiable and non-modifiable epigenetic factors. Advances in pharmacogenomics promise a better understanding of immune responses triggered by adjuvants, enabling anticipation of long-term adverse effects and potentially informing practices in plastic and reconstructive surgery, particularly involving silicone-based bioprostheses.

Ethical considerationsThis work adheres to current regulations on bioethical research.

FundingNo external funding was received for the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We gratefully acknowledge Gloria Vásquez Duque, MD, DrSci, Professor of the Rheumatology Program at the School of Medicine of Universidad de Antioquia.