The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is challenging, especially if the patient has concomitant infectious symptoms. Furthermore, the overlap of immune-mediated and infectious pathologies is not uncommon.

ObjectiveTo report a rare case of association between tuberculosis and sarcoidosis

Materials and methodsDescription of the clinical characteristics of a patient who presented with sarcoidosis superimposed on tuberculosis.

ResultsThe case of a 29-year-old man with ocular, cutaneous, and systemic symptoms is described. Uveitis and chronic non-caseating granulomatous findings were diagnosed in the skin, lungs, and lymph nodes. Suspicion of tuberculosis led to positive molecular biology tests only in the lymph node biopsy. An overlap of sarcoidosis and tuberculosis was determined, and combined treatment with glucocorticoids and anti-tuberculosis agents was initiated, resulting in improvement of the patient.

ConclusionsSarcoidosis and tuberculosis share characteristics from their aetiology to clinical manifestations, posing a challenge in clinical differentiation. Cases have been documented where both diseases overlap in the same patient.

El diagnóstico de sarcoidosis significa un desafío, en especial si el paciente cursa con síntomas infecciosos concomitantes. Además, la superposición de patologías inmunomediadas e infecciosas no es infrecuente.

ObjetivosReportar un caso infrecuente de asociación entre tuberculosis y sarcoidosis.

Materiales y métodosDescripción de las características clínicas de un paciente que cursó con un cuadro de sarcoidosis sobrepuesto a tuberculosis.

ResultadosSe describe el caso de un hombre de 29 años con síntomas oculares, cutáneos y sistémicos. Se diagnosticó uveítis y hallazgos granulomatosos no caseificantes crónicos en piel, pulmón y ganglio linfático. La sospecha de tuberculosis llevó a pruebas de biología molecular positivas en trazas solo en la biopsia de ganglio linfático. Se determinó una superposición de sarcoidosis y tuberculosis, y se inició un tratamiento combinado con glucocorticoides y antituberculosos, lo que resultó en una mejoría del paciente.

ConclusionesLa sarcoidosis y la tuberculosis comparten características desde su etiología hasta sus manifestaciones clínicas, lo que representa un desafío para su diferenciación clínica. Se han documentado casos en los que ambas enfermedades se superponen en un mismo paciente; este se suma a dicho grupo de coexistencia.

Sarcoidosis is a rare, multi-organ disease characterized by the formation of non-caseating granulomas.1 The most affected organs include the skin (where the condition was initially described), the eyes, the lungs, and the lymph nodes.2 Although the global epidemiology of sarcoidosis is not yet fully established, it is known to be particularly prevalent among African-American patients and typically manifests between the ages of 20 and 39.3,4 Mycobacteria have been associated with sarcoidosis, as granulomatous responses are crucial for host defense against these microorganisms. While granulomas in sarcoidosis are non-caseating, those found in tuberculosis (TB) are caseating. Additionally, genetic material from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) has been detected in patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis.5

Conversely, M. tuberculosis infection is one of the leading causes of infectious disease-related mortality worldwide, with humans serving as the natural reservoir for this bacteria.6 The hematogenous dissemination of M. tuberculosis can impact multiple organs, including the eyes, lymph nodes, skin, liver, and kidneys. Although the simultaneous occurrence of sarcoidosis and TB is rare, cases have been documented in which both conditions coexist.7,8 This report describes a patient with multi-system involvement attributable to sarcoidosis, in whom genetic material from M. tuberculosis was identified in a histological sample of a lymph node.

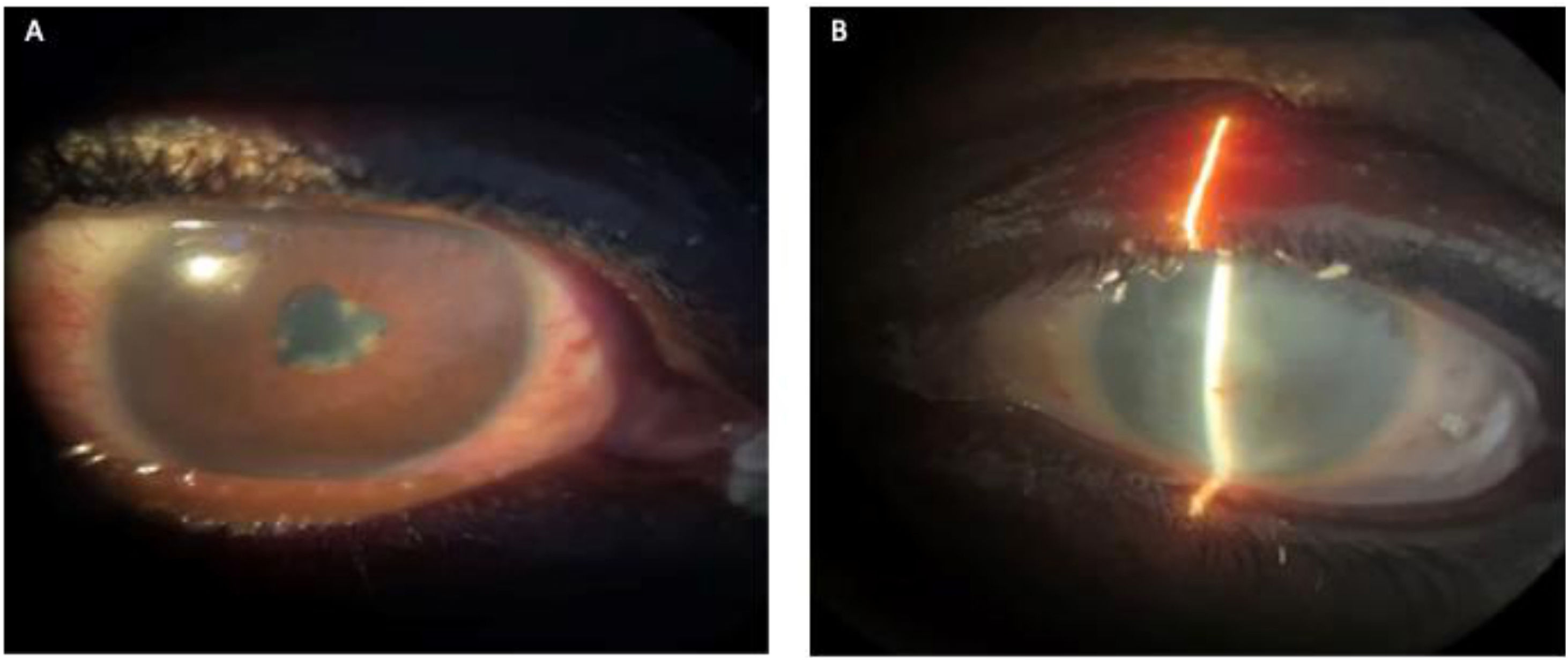

Case presentationA 29-year-old Black male patient presented to the emergency department with a five-month history of a red right eye, accompanied by ocular pain, photopsia, epiphora, photophobia, and decreased visual acuity. He had been treated with 1% prednisolone eye drops, which provided only partial relief of symptoms. He was initially evaluated by the Ophthalmology Department, which diagnosed him with non-granulomatous right anterior uveitis. The left eye, which had a history of visual loss 10 years before his current consultation, showed media opacity.

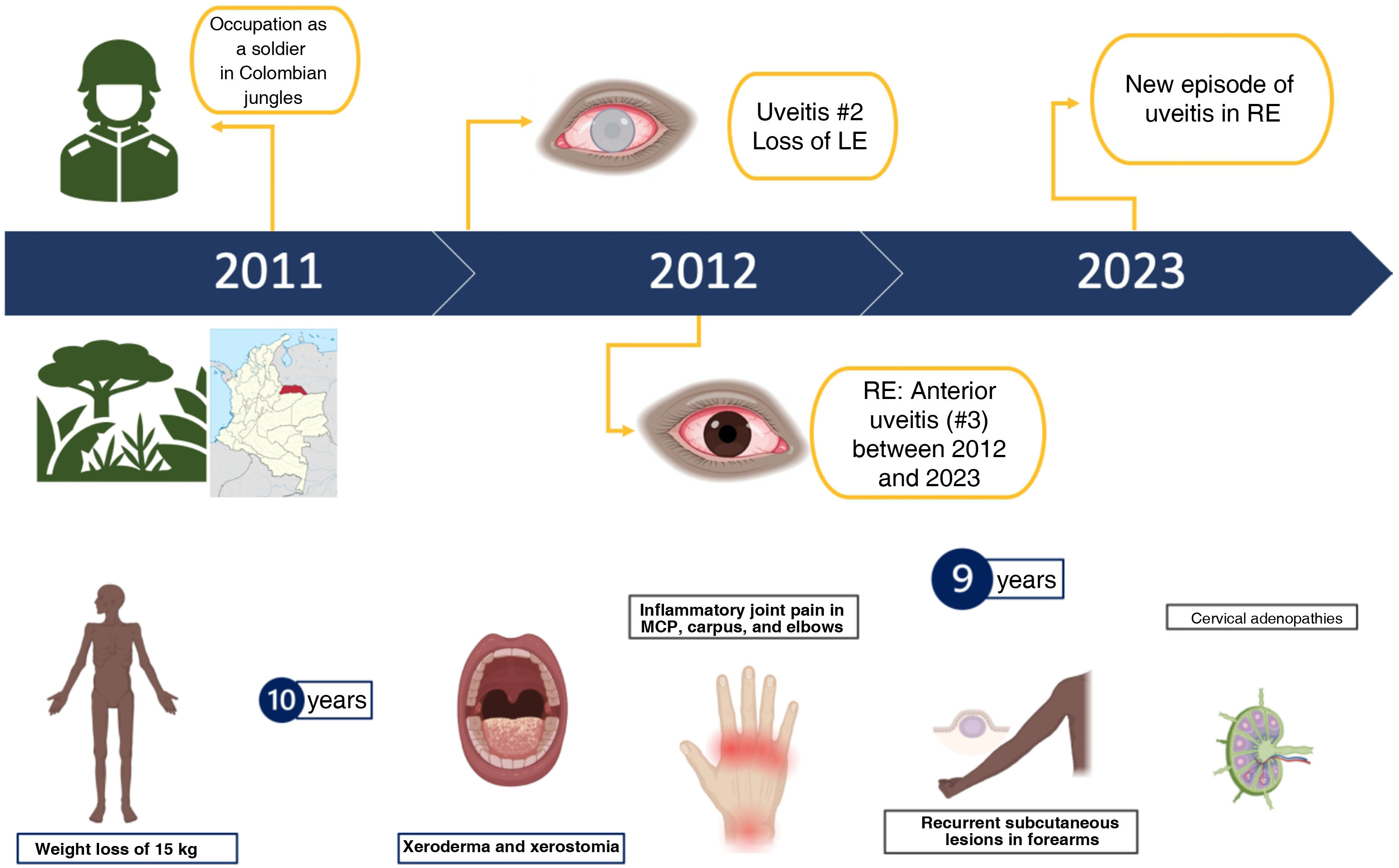

Upon reviewing his medical history, the patient reported long-standing cervical adenopathy, as well as asthenia and weight loss, suggesting a systemic disease with ocular involvement. Further detailing his illness history, the patient noted that his first episode of visual symptoms occurred a year after serving as a soldier in the jungles of Colombia, where he experienced similar symptoms in his left eye. After a second episode, he completely lost vision in that eye, but no clear diagnosis was established at that time. Over the subsequent eight years, he experienced intermittent similar conditions in the right eye, treated with prednisone eye drops, though with only partial improvement. Additionally, he reported a weight loss of 15 kg, xerodermia, xerostomia, inflammatory joint pain in the metacarpophalangeal joints, carpus, and elbows, bilateral cervical adenopathy, and recurrent subcutaneous lesions on his forearms. His relevant medical history included occasional use of alcohol, tobacco, and cannabinoids. Fig. 1 depicts the timeline of the patient's medical history.

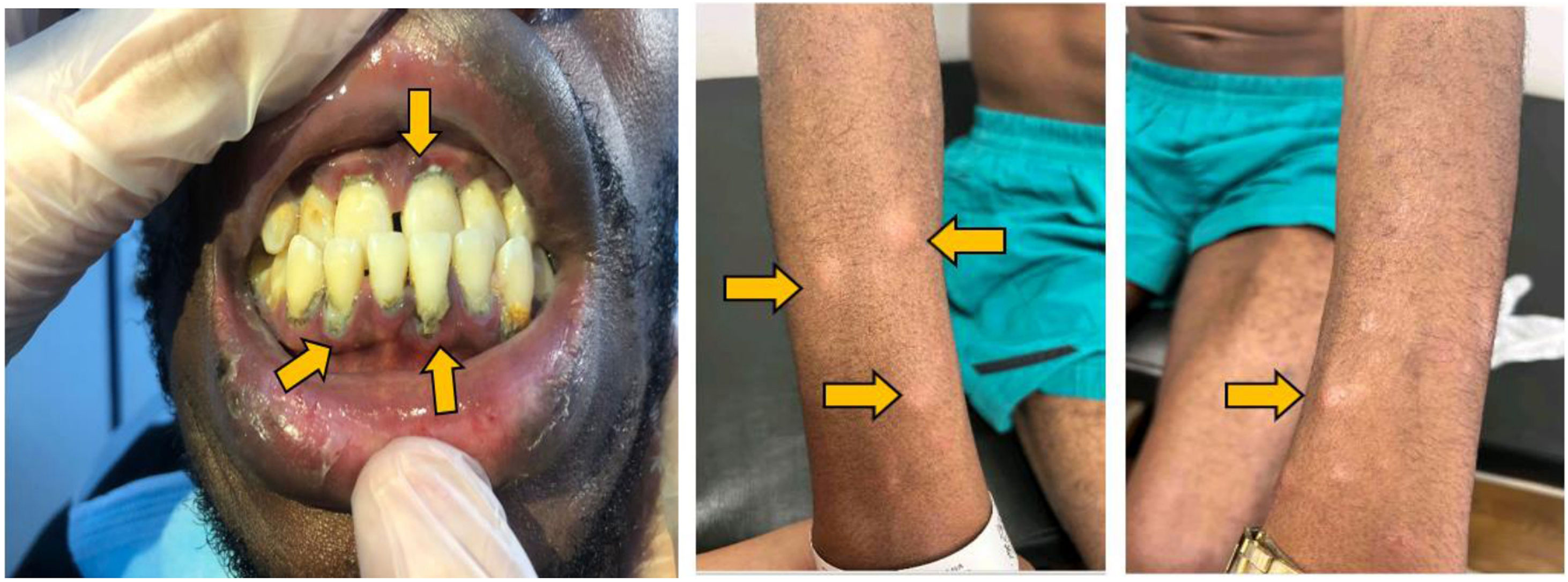

During physical examination, the patient appeared thin and had opacity in the left eye, red right eye and dyscoria (Fig. 2). Examination of the head and neck revealed white-gray membranes on the gums and interdental spaces, as well as painless cervical adenomegaly. Pulmonary auscultation showed thick bilateral rales. The liver was enlarged, soft in consistency, and non-tender to palpation. In addition to marked xerodermia, the skin exhibited hypochromic plaques and nodules with a slightly scaly surface (Fig. 3). Generalized muscle atrophy was also noticed, although neurological affection was absent.

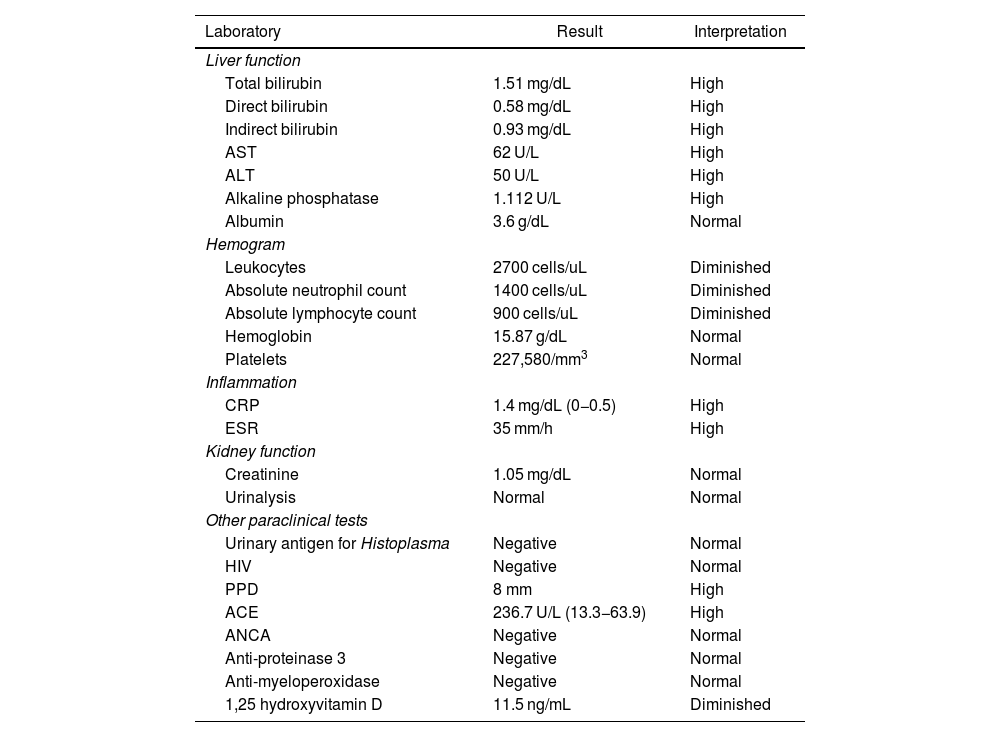

Initial complementary studies included a chest X-ray, which revealed parahilar adenopathy and bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Liver function tests indicated a cholestatic pattern, with significantly elevated alkaline phosphatase and C-reactive protein levels. These results, along with the findings from the physical and laboratory assessments, prompted the request for contrast-enhanced CT scans of the neck, chest, and abdomen. Given the multi-system involvement, autoimmune/rheumatologic etiologies and infections were the primary considerations. 1,25 hydroxyvitamin D levels were found to be decreased. Table 1 summarizes the findings from the studies performed on the patient.

Paraclinical tests of the patient.

| Laboratory | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Liver function | ||

| Total bilirubin | 1.51 mg/dL | High |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.58 mg/dL | High |

| Indirect bilirubin | 0.93 mg/dL | High |

| AST | 62 U/L | High |

| ALT | 50 U/L | High |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 1.112 U/L | High |

| Albumin | 3.6 g/dL | Normal |

| Hemogram | ||

| Leukocytes | 2700 cells/uL | Diminished |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 1400 cells/uL | Diminished |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | 900 cells/uL | Diminished |

| Hemoglobin | 15.87 g/dL | Normal |

| Platelets | 227,580/mm3 | Normal |

| Inflammation | ||

| CRP | 1.4 mg/dL (0−0.5) | High |

| ESR | 35 mm/h | High |

| Kidney function | ||

| Creatinine | 1.05 mg/dL | Normal |

| Urinalysis | Normal | Normal |

| Other paraclinical tests | ||

| Urinary antigen for Histoplasma | Negative | Normal |

| HIV | Negative | Normal |

| PPD | 8 mm | High |

| ACE | 236.7 U/L (13.3−63.9) | High |

| ANCA | Negative | Normal |

| Anti-proteinase 3 | Negative | Normal |

| Anti-myeloperoxidase | Negative | Normal |

| 1,25 hydroxyvitamin D | 11.5 ng/mL | Diminished |

AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PPD: Purified proteic derivate; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ANCA: antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.

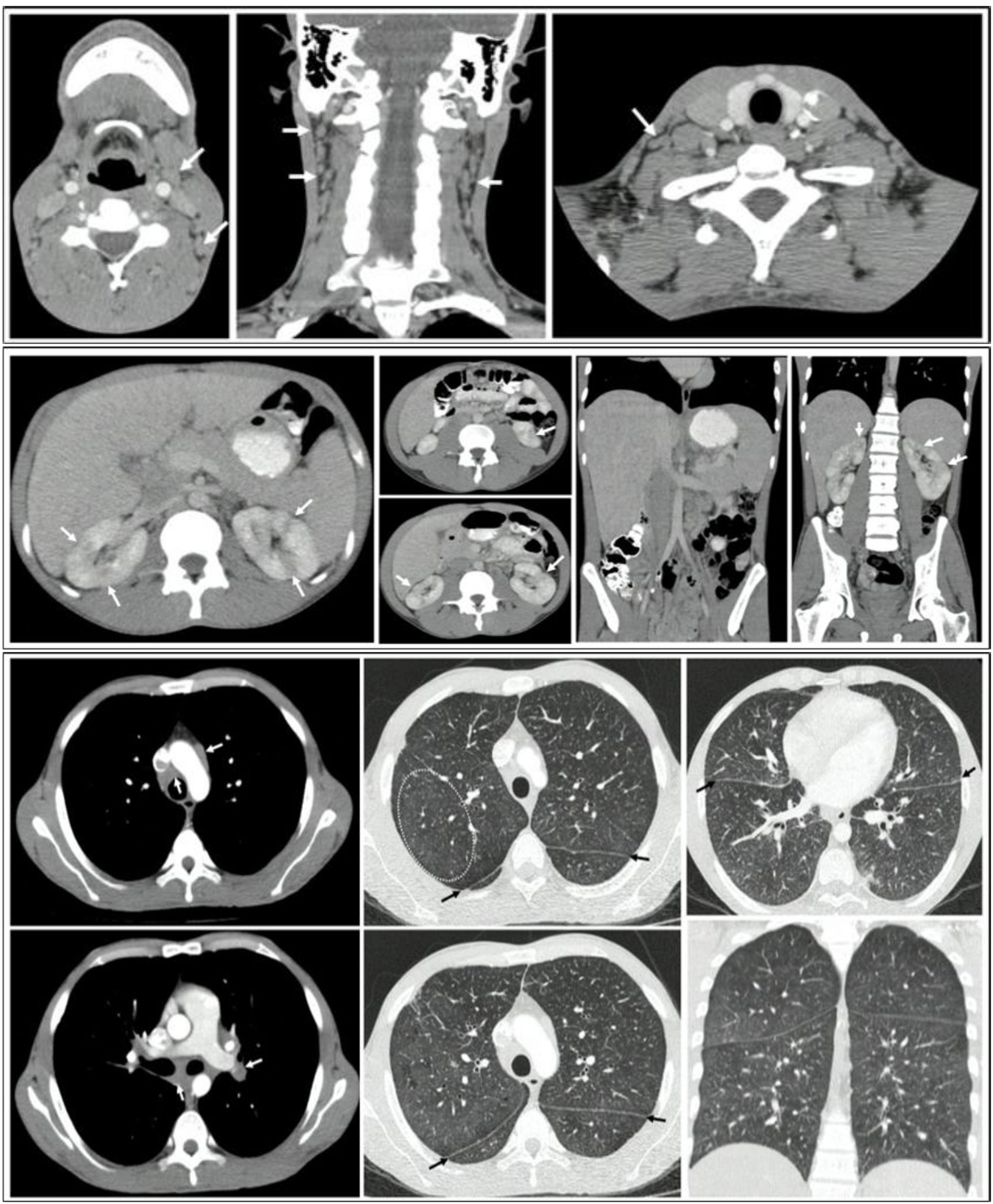

The contrast-enhanced CT of the chest revealed multiple lymphadenopathies in the mediastinum, particularly in the bilateral parahilar, prevascular, pretracheal, and subcarinal regions. Thickening of the bronchial walls was noted, predominantly in the central area and extending toward the lower lobes; multiple micronodules with soft-tissue density forming a miliary pattern, with diameters less than 3 mm in both lung parenchyma were noted.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT revealed para-aortic, interaortocaval, and retroperitoneal adenomegalies, along with hepatomegaly featuring multiple small hypodense nodular lesions suggestive of microabscesses. Areas of non-enhancement with a wedge-shaped morphology were also observed in both kidneys, indicating focal nephritis (Fig. 4).

CT scans of the neck, thorax, and abdomen: A) Presence of bilateral cervical adenomegalies. B) Presence of multiple adenopathies in the mediastinum, mainly in the bilateral parahilar, prevascular, pretracheal, and subcarinal regions. Thickening of the bronchial walls, predominantly in the central area and towards the lower lobes, in addition to multiple micronodules with soft-tissue density that formed a miliary pattern, with diameters less than 3 mm, present in both lung parenchymas. C) Nodular lesions in the liver and kidney, with hepatomegaly and splenomegaly.

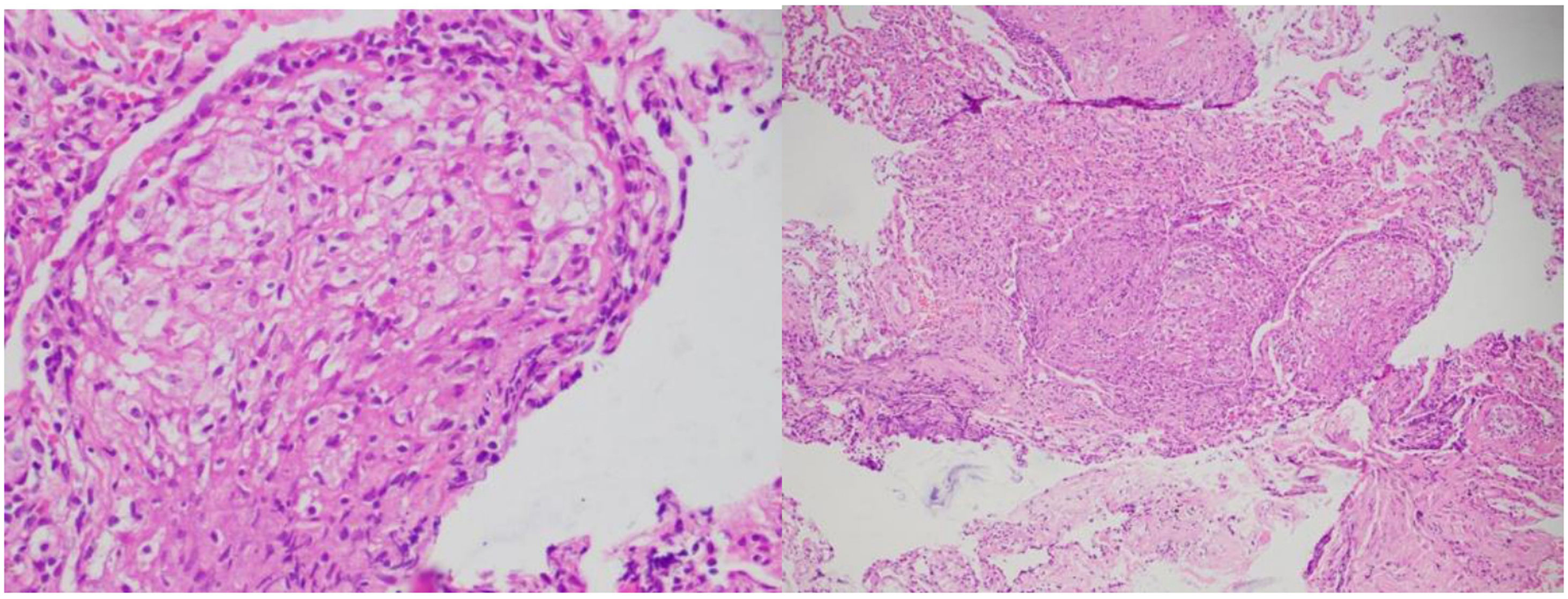

The patient's epidemiological history, including his stay in the jungle, while serving as a soldier, combined with weight loss and involvement of the eyes, lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and kidneys, raised suspicions of tuberculosis (TB) or histoplasmosis as potential infectious causes. A Histoplasma urinary antigen test was negative. Lung samples obtained through bronchoalveolar lavage showed negative results for bacilloscopy, GenXpert, and M. tuberculosis cultures. Skin biopsies were taken from the upper limbs and cervical nodes, along with transbronchial biopsies via fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Histological analysis of these samples (Fig. 5) revealed multiple naked (non-caseating) granulomas, consistent with a chronic sarcoid-type non-necrotizing granulomatous process. Ziehl-Neelsen, PAS, and Gomori histological stains were negative, ruling out a concurrent infection at that time. Additionally, elevated serum angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were noted.

It is important to highlight that in the histopathological analysis of the skin nodules, the Pathology Department observed lymphocytic infiltration around the nerve structures, with no evidence of destruction or alteration of those structures. Considering this, with the collaboration with the Dermatology and Pathology departments, it was decided to rule out the paucibacillary form of leprosy. Specific studies were conducted, including bacilloscopy of lymph from the ears and elbows, Fite Faraco stains, and molecular studies. All analyses yielded negative results for Mycobacterium leprae (M. leprae). The combination of these findings, along with the absence of suggestive clinical manifestations, allowed us to exclude the possibility of an M. leprae infection.

Given that TB was the primary differential diagnosis, PCR testing for M. tuberculosis (GenXpert MTB-RIF Ultra) was performed on lymph node and lung tissue biopsies. The result was negative for lung tissue but trace positive in the adenopathy.

With these results, a multidisciplinary meeting involving Internal Medicine, Rheumatology, Pulmonology, and Infectology was convened, leading to a diagnosis of sarcoidosis with multisystem involvement and a concomitant TB infection.

It was decided to initiate anti-tuberculosis treatment alongside systemic glucocorticoids (prednisone 20 mg orally daily). The patient demonstrated positive progress, with a gradual improvement in conjunctival redness and notable recovery of visual acuity. Additionally, a reduction and eventual disappearance of the skin lesions were observed, along with significant relief of polyarticular pain. During clinical follow-up, the patient exhibited good tolerance to both treatments, with no adverse reactions. Cultures for M. tuberculosis from the described biopsies were negative at 42 days.

DiscussionMultisystem involvement is common in both rheumatic and infectious diseases, presenting a significant challenge for clinicians in diagnosis and treatment. In our patient, several systems were affected, including pulmonary, lymphatic, ocular, dermatological, hepatic, and renal. It is important to highlight that multiple findings during the patient's history and physical examination were critical for guiding the diagnosis. This reinforces that clinical history remains the cornerstone of medical practice, even in highly complex cases. Baughman et al. published the results of the ACCESS case-control study, which identified the organ systems affected by sarcoidosis, as well as the race and age of the patients affected by this condition.2 Our patient exhibited involvement in nine of the domains described in this study, with the most notable being the eyes, skin, lungs, liver, and kidneys.2,9,10

Histology played a key role in establishing a diagnosis, particularly standing out the presence of a sarcoid granulomatous reaction in the skin, lungs, and lymph nodes. This finding helped orient our understanding of the condition's etiology, pointing towards infections and immune-mediated diseases. Various types of granulomas have been identified, including tuberculoid, suppurative, sarcoid, necrobiotic, foreign body, Messy granuloma, xanthogranuloma, and Miescher granuloma.11,12

Although none of these granuloma types are pathognomonic for a specific condition, they tend to be associated with certain diseases. For instance, tuberculoid granuloma is characterized by central caseous necrosis surrounded by a crown of lymphocytes, typically associated with tuberculosis (TB). In our patient, we identified a sarcoid granuloma (in the skin, lungs, and lymph nodes) that lacked central necrosis and had a less pronounced peripheral cellular infiltrate compared to tuberculoid granuloma. For this reason, it is often referred to as a naked granuloma, which is more commonly seen in cases of sarcoidosis. Asteroid and Schaumann’s bodies are remarkable findings for pathologists examining this type of granuloma.11,13

Our patient presented a wide range of clinical, paraclinical, and histological features consistent with sarcoidosis. According to the 2020 sarcoidosis diagnostic guideline,14 this patient exhibited uveitis, erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar adenopathy, and perilymphatic nodes, strongly suggesting the presence of this disease. Additionally, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, peribronchial thickening, extrapulmonary adenomegaly, and elevated levels of angiotensin-converting enzyme14 and alkaline phosphatase were also noticed, further supporting the diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

The diagnosis of TB was based on the aforementioned clinical features, along with the presence of M. tuberculosis genetic material detected in a molecular biology test on lymph node tissue.

Clinically, paraclinically, and histologically, sarcoidosis and TB share similar features, making differentiation particularly challenging in countries with high TB prevalence.1,15,16 Molecular studies have even shown the presence of M. tuberculosis genetic material in patients with sarcoidosis, suggesting that mycobacterial antigens may trigger the sarcoid granulomatous response.15,17 Elevated levels of mycobacteria-specific heat shock proteins and angiotensin-converting enzyme have been observed in both disorders.18

The coexistence of these two diseases has been reported in the literature, with cases of simultaneous presentation or sarcoidosis developing after TB diagnosis.7,19–24

A spectrum of disorders has been proposed, with TB at one end and sarcoidosis at the other. Depending on the intensity of the host immune response, patients may present with an intermediate spectrum referred to as “tuberculosis-sarcoidosis-like,” where features of both diseases coexist.8,21,24,25

In complex diseases affecting multiple systems, promoting multidisciplinary collaboration is essential for achieving timely etiological diagnoses. This approach enables treatment and enhances patient prognosis. Our case exemplifies a successful diagnostic strategy and management of a granulomatous disease with overlapping etiologies: tuberculosis and sarcoidosis.

Ethical responsibilitiesThe authors have obtained informed consent from the patients mentioned in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author. This study poses no risk, as it only describes clinical data from the patient without any interventions. The author confirms that informed consent has been obtained for the publication of the patient’s data and images.

FinancingNone.

We thank the Asociacion Colombiana de Reumatologia (ASOREUMA) for their support of continuing medical education.

We extend our gratitude to the members of the Ophthalmology, Rheumatology, Pulmonology, Dermatology, and Internal Medicine groups for their valuable comments that contributed to the writing of this manuscript.