In the last 15 years only a few cases of Pasteurella multocida (P. multocida) total knee arthroplasty infection have been published, mostly related to cat or dog bites or scratches. We report a case of P. multocida total knee arthroplasty infection in a 64-year-old patient, 10 days after being scratched and bitten by his cat. The patient was successfully treated with debridement and tibial interspacer exchange and antibiotic treatment for 6 weeks. Antimicrobial prophylaxis should be considered in cat or dog bites or scratches victims with prosthetic joints.

En los últimos 15 años se han descrito solo unos pocos casos de infección de prótesis total de rodilla por Pasteurella multocida (P. multocida). La mayoría de estos casos están relacionados con un antecedente de mordedura o arañazo de perro o gato. Presentamos un caso de infección de prótesis de rodilla por P. multocida en un paciente de 64 años, que 10 días antes había sufrido heridas en la pierna por arañazos y mordeduras de su gato. El paciente fue tratado mediante artrotomía de limpieza y desbridamiento con recambio del polietileno, seguido de 6 semanas de tratamiento antibiótico con un buen resultado. La profilaxis antibiótica debería valorarse en los portadores de una prótesis que presenten una herida por mordedura o arañazo de perro o de gato.

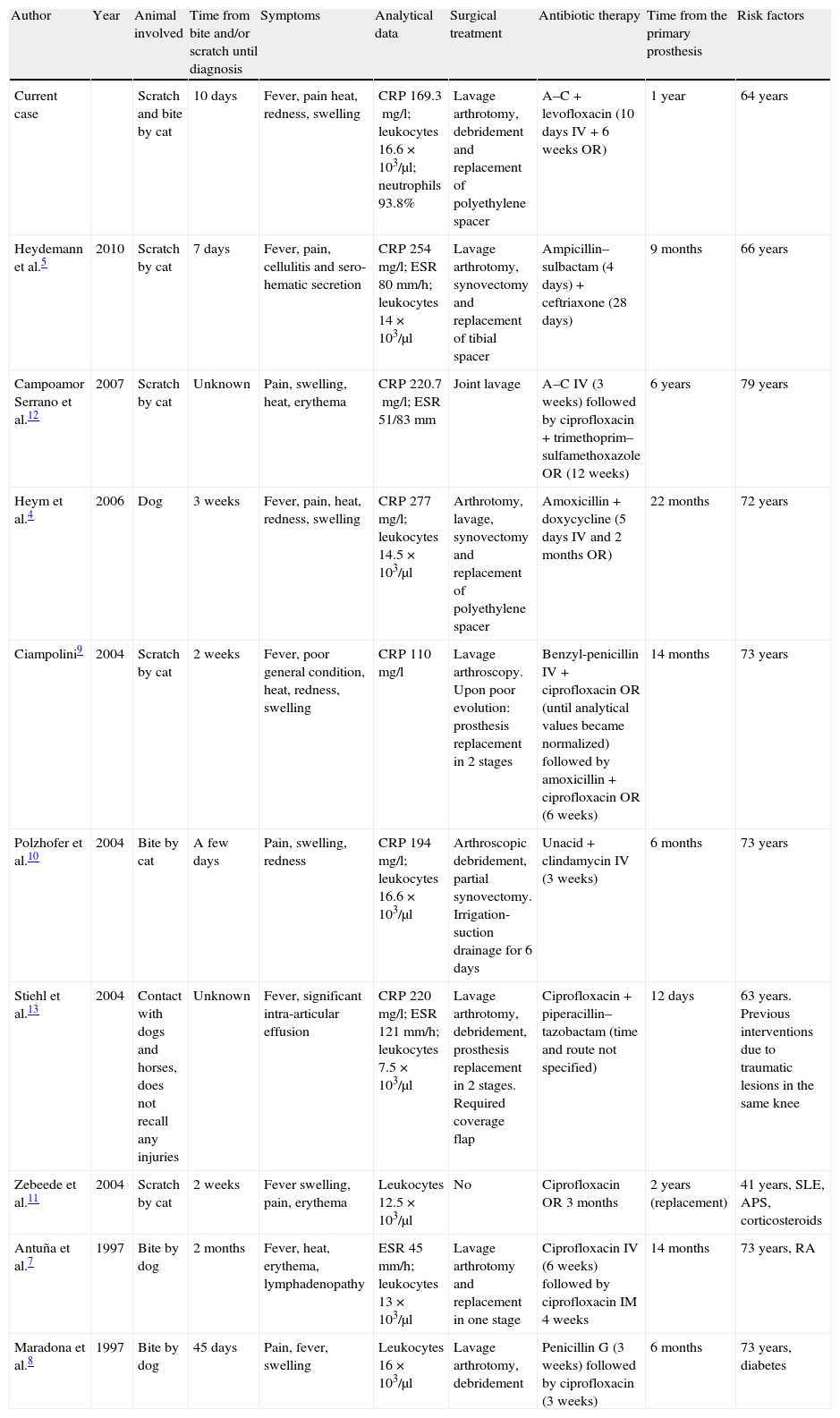

Prosthetic infection is one of the most severe complications that can take place in arthroplasty surgery. The incidence of infection is 1–2% in the first 2 years after surgery, in both hip and knee arthroplasties.1–5 The most common pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus, followed by coagulase-negative staphylococci and streptococci, although Gram-negative bacilli have also been isolated in some cases.4–6 In the last 15 years there have been some reports of prosthetic infection by Pasteurella multocida (P. multocida) related to bites and scratches by cats and dogs (Table 1).4,5,7–13

Cases of prosthetic infection by P. multocida described in the past 15 years.

| Author | Year | Animal involved | Time from bite and/or scratch until diagnosis | Symptoms | Analytical data | Surgical treatment | Antibiotic therapy | Time from the primary prosthesis | Risk factors |

| Current case | Scratch and bite by cat | 10 days | Fever, pain heat, redness, swelling | CRP 169.3mg/l; leukocytes 16.6×103/μl; neutrophils 93.8% | Lavage arthrotomy, debridement and replacement of polyethylene spacer | A–C+levofloxacin (10 days IV+6 weeks OR) | 1 year | 64 years | |

| Heydemann et al.5 | 2010 | Scratch by cat | 7 days | Fever, pain, cellulitis and sero-hematic secretion | CRP 254mg/l; ESR 80mm/h; leukocytes 14×103/μl | Lavage arthrotomy, synovectomy and replacement of tibial spacer | Ampicillin–sulbactam (4 days)+ceftriaxone (28 days) | 9 months | 66 years |

| Campoamor Serrano et al.12 | 2007 | Scratch by cat | Unknown | Pain, swelling, heat, erythema | CRP 220.7mg/l; ESR 51/83mm | Joint lavage | A–C IV (3 weeks) followed by ciprofloxacin+trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole OR (12 weeks) | 6 years | 79 years |

| Heym et al.4 | 2006 | Dog | 3 weeks | Fever, pain, heat, redness, swelling | CRP 277mg/l; leukocytes 14.5×103/μl | Arthrotomy, lavage, synovectomy and replacement of polyethylene spacer | Amoxicillin+doxycycline (5 days IV and 2 months OR) | 22 months | 72 years |

| Ciampolini9 | 2004 | Scratch by cat | 2 weeks | Fever, poor general condition, heat, redness, swelling | CRP 110mg/l | Lavage arthroscopy. Upon poor evolution: prosthesis replacement in 2 stages | Benzyl-penicillin IV+ciprofloxacin OR (until analytical values became normalized) followed by amoxicillin+ciprofloxacin OR (6 weeks) | 14 months | 73 years |

| Polzhofer et al.10 | 2004 | Bite by cat | A few days | Pain, swelling, redness | CRP 194mg/l; leukocytes 16.6×103/μl | Arthroscopic debridement, partial synovectomy. Irrigation-suction drainage for 6 days | Unacid+clindamycin IV (3 weeks) | 6 months | 73 years |

| Stiehl et al.13 | 2004 | Contact with dogs and horses, does not recall any injuries | Unknown | Fever, significant intra-articular effusion | CRP 220mg/l; ESR 121mm/h; leukocytes 7.5×103/μl | Lavage arthrotomy, debridement, prosthesis replacement in 2 stages. Required coverage flap | Ciprofloxacin+piperacillin–tazobactam (time and route not specified) | 12 days | 63 years. Previous interventions due to traumatic lesions in the same knee |

| Zebeede et al.11 | 2004 | Scratch by cat | 2 weeks | Fever swelling, pain, erythema | Leukocytes 12.5×103/μl | No | Ciprofloxacin OR 3 months | 2 years (replacement) | 41 years, SLE, APS, corticosteroids |

| Antuña et al.7 | 1997 | Bite by dog | 2 months | Fever, heat, erythema, lymphadenopathy | ESR 45mm/h; leukocytes 13×103/μl | Lavage arthrotomy and replacement in one stage | Ciprofloxacin IV (6 weeks) followed by ciprofloxacin IM 4 weeks | 14 months | 73 years, RA |

| Maradona et al.8 | 1997 | Bite by dog | 45 days | Pain, fever, swelling | Leukocytes 16×103/μl | Lavage arthrotomy, debridement | Penicillin G (3 weeks) followed by ciprofloxacin (3 weeks) | 6 months | 73 years, diabetes |

A–C: amoxicillin–clavulanate; APS: antiphospholipid syndrome; CRP: C reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IM: intramuscular; IV: intravenous; OR: orally; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus.

P. multocida is a Gram-negative coccobacillus. It is common in the habitual flora of wild and domestic animals, especially dogs and cats. P. multocida has been frequently associated with infections caused by bites and scratches from dogs and cats.5 Although in most cases the infection remains confined to the entry point, causing cellulitis and abscess, occasionally osteomyelitis and septic arthritis can also appear, and, more rarely, prosthetic infection. Systemically, it may lead to respiratory infections, meningitis and septicemia.4,12,13 Transmission from animals to humans after a scratch or bite can occur via hematogenous spread or local contamination, although the former is considered more common.5,13 The risk factors described for prosthetic infection by P. multocida include immunosuppression, advanced age, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, the number of previous surgeries, kidney failure, intraoperative blood loss and the number days of postoperative drainage.4,5,7,8,11

The treatment of choice is intravenous antibiotic therapy (second or third generation cephalosporins or penicillin). A surgical intervention involving arthrotomy for joint lavage and debridement should be added in cases of prosthetic infection. If necessary, replacement of a component or removal of the prosthesis can also be carried out.4,5

Case reportWe present the case of a 64-year-old white male who attended the emergency unit due to symptoms including chills, dysthermia and fever of 38°C, with 24h evolution. Subsequently, he began to suffer severe pain in the right knee which evolved into edema and redness, as well as joint stiffness. Upon examination, he presented heat and redness in the right knee, limitation of joint movement range with severe pain upon flexion, positive patellar tap sign and intense pain upon knee palpation, especially in its medial side. He also presented a small wound on the lateral side of the distal third of his right leg, with no signs of local infection. Axillary temperature was 37.8°C. The rest of the examination was normal, with no relevant findings.

As background history, the patient reported that 10 days before attending the ER and 9 days before the onset of symptoms, he suffered the bite and scratch of a cat on his right leg, in the pretibial area, which were cured at his local health center.

In his youth he underwent intervention for a posttraumatic right patellectomy. Subsequently, at the age of 56, 7 years before the arthroplasty, he underwent valgus closure osteotomy in the right tibia, using a staple for osteosynthesis. One year before the current symptoms, the patient had undergone total knee arthroplasty on the right side (total knee prosthesis with rotating platform and cementing of all components), which evolved favorably, achieving 0° extension, 100° flexion and painless gait.

The relevant medical history also included familial hypercholesterolemia and arterial hypertension.

We performed right knee arthrocentesis under sterile conditions, obtaining an opalescent and whitish-yellow liquid. We requested a biochemical analysis and culture of the synovial fluid. We performed a blood test and requested its biochemical analysis (with determination of C-reactive protein [CRP]), hemogram, hemostasis and blood culture. These tests revealed the following results: the synovial fluid presented a cell count over 10,000/μl, with 95% of polymorphonuclear cells (PMN), and a total protein count of 4.9g/dl. There was also leukocytosis (16.6×103/μl) with neutrophilia (93.8%) and the CRP result was 169.3mg/l (normal range: 0–8mg/l). In the following days we obtained the results of the culture. Blood culture was negative, but the synovial fluid culture was positive for P. multocida (with antibiogram susceptible to amoxicillin/clavulanate, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin and cotrimoxazole).

The patient was operated 72h after admission at the emergency unit. The intervention included joint lavage, synovectomy and replacement of the polyethylene spacer component. The culture of synovial fluid and synovial membrane samples taken intraoperatively was positive for P. multocida. The patient was treated for 10 days with dual intravenous (iv) antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin–clavulanate 1g/8h plus levofloxacin 500mg/12h). He presented a favorable evolution and oral antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin/clavulanate 875/125mg plus levofloxacin 500mg/12h was maintained for 6 weeks.

Ten weeks after the intervention, the patient remained asymptomatic and afebrile and laboratory parameters had become normalized (CRP 1mg/l, leukocytes 8.6×103/μl with 42.2% neutrophils). Two years after surgery, the patient is asymptomatic, with a joint movement range of 0° extension and 90° flexion. The knee has a good external appearance; there is no joint effusion; it is neither warm nor edematous and the patient is able to walk without aids and does not require analgesia.

DiscussionP. multocida is a Gram-negative coccobacillus which has been infrequently described as the cause of prosthetic infections. Virtually all published cases of prosthetic knee infection by P. multocida, including the case presented, have a documented history of scratches and bites by cats and dogs (Table 1).4,5,7–13 It is important to perform a thorough anamnesis and question the patient about possible contact with animals upon suspicion of knee prosthesis infection. If there is a history of scratch or bite by a dog or cat and symptoms of prosthetic infection, then this etiology should be considered in order to implement antibiotic coverage until the results of cultures are obtained. Symptoms are nonspecific and similar to prosthetic knee infection by other pathogens, including fever, pain, swelling, heat and redness. These clinical data are supported by laboratory data such as an increase in C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and leukocytosis, which, like the symptoms, are not only highly sensitive, but also highly unspecific.5 The definitive diagnosis is obtained through the result of cultures and biochemical analysis of the synovial fluid.12

It is difficult to establish the latency time between the injury and the onset of symptoms. This varies between 7 days and 2 months, thus making it difficult to diagnose, since patients may not remember the scratch or bite or may not give it any importance (Table 1).9

Numerous risk factors which facilitate prosthetic infection by P. multocida have been reported.4,5,11 However, if we analyze the 9 cases described in the literature in the last 15 years, only 4 presented any of these risk factors: rheumatoid arthritis,7 systemic lupus erythematosus treated with corticosteroids,11 diabetes8 and multiple surgical interventions (Table 1).13 Despite being a risk factor, advanced age cannot be considered a differentiating factor, since most patients with knee prostheses are usually over 60 years old. Therefore, the existence of risk factors should not be a decisive factor when considering this diagnosis.

When faced with acute infection of knee prostheses, empirical antibiotic treatment should be started immediately until the results of cultures and antibiograms are available, and the indication of surgery should be evaluated.3 Some authors suggest that prolonged antibiotic treatment without surgery may be sufficient in selected cases.11 Most reports indicate surgical intervention followed by antibiotic treatment, and the main discussion focuses on the choice of surgical approach option. Some cases have reported that arthroscopic debridement followed by drainage with irrigation and antibiotic therapy may be a valid treatment.10 However, most authors prefer joint lavage arthrotomy with aggressive debridement followed by appropriate antibiotic therapy, with or without prosthetic replacement.3–5,8,9,14 Prosthetic replacement can be avoided when the following criteria are met4: (1) acute infection, (2) the microorganism is identified, (3) the microorganism is sensitive to oral antibiotics, (4) the antibiotics required for treatment are well tolerated by the patient, and (5) there is no loosening of the prosthetic components. In contrast, other authors argue the need for prosthetic replacement in all cases.7 One accepted option is to perform joint lavage arthrotomy and adequate debridement, and to assess the condition of the soft tissues, bone and prosthetic components.14 Prosthetic replacement is necessary when there is loosening of prosthetic components or bone involvement. However, if the components have become loosened they can be preserved.4,5,9,14 Moving components (polyethylene spacers) can be replaced.4,5 If prosthetic replacement is necessary, it can be performed in a single surgical action,3,7,14 although most authors choose to perform replacement in 2 stages.3,4,9,13,14 Based on our experience, we believe that the treatment of choice for suspected acute infection of knee prosthesis is to start empirical antibiotic therapy as soon as possible (an antibiotic that covers P. multocida should be chosen if there is a history of scratch or bite by a dog or cat), followed by joint lavage arthrotomy with aggressive debridement, as well as replacement of the polyethylene spacer if the prosthesis model allows it. After the intervention, antibiotic treatment should be maintained for 6–12 weeks, ensuring that the analytical parameters become normalized. The most commonly used antibiotics include penicillin, amoxicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate, cefuroxime, tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones.5,13 In the event that the prosthetic components have become loosened, we believe that replacement should be carried out in 2 stages, leaving an intermediate period of 4–6 weeks with antibiotic therapy, and placing the new prosthesis in a second stage once the analytical parameters have become normalized. In our case, the infection of the knee prosthesis was very acute (24h and the operation was performed at 72h), which may be one of the reasons for the successful treatment through debridement, replacement of moving components and antibiotic therapy without replacement of the prosthesis.3,4,14

ConclusionsEarly diagnosis is very important in cases of knee prosthesis infection. P. multocida should be considered as a potential pathogen causing the infection if there is a history of bite or scratch by a dog or cat. Treatment should be initiated urgently upon confirmed infection of knee prosthesis. The need for prophylactic antibiotic coverage should be considered in patients with a knee prosthesis who attend consultation due to a scratch or bite by a dog or cat.7–9

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence V.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that this work does not reflect any patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Please cite this article as: Miranda I, Angulo M, Amaya JV. Infección aguda de prótesis total de rodilla tras mordedura y arañazo de gato: caso clínico y revisión de la bibliografía. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:300–5.