There is currently sufficient clinical evidence to recommend tranexamic acid (TXA) for reducing post-operative blood loss in total knee and hip arthroplasty, however, its optimal dose and administration regimes are unknown.

ObjectiveAnalyse effectiveness and safety of TXA in total hip and knee arthroplasty using 2 grammes (g) intravenously in two different regimes.

Material and methodsA prospective randomised intervention study was conducted on a total of 240 patients. The patients were divided into 3 groups: (1) control; (2) 1g of TXA intraoperative, followed by another postoperative; and (3) 2g preoperative. Each group consisted of 40 patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty, and 40 total hip arthroplasty.

Postoperative blood loss, transfusion rate, and thromboembolic complications were studied.

ResultsThere were significant differences (P<.005) when comparing mean total blood loss and transfusion between group 1 and 2, and between group 1 and 3, but not between the two TXA groups (2 and 3). The authors only recorded one complication in group 1 (deep vein thrombosis).

DiscusionThis study was not performed to investigate the already well established effectiveness of TXA, but to confirm if 2 empirical intravenous g is safe, and what is most beneficial regimen.

In conclusion, according to the literature, both proven patterns of 2g intravenous of TXA are effective in reducing blood loss and transfusion requirements, without increasing the complication rate.

Actualmente, para disminuir el sangrado postoperatorio en la cirugía de artroplastia de cadera y rodilla, hay suficiente evidencia científica para recomendar el uso del ácido tranexámico (ATX), sin embargo, la dosis y pauta ideal para obtener su máximo beneficio es desconocida.

ObjetivoAnalizar la efectividad y seguridad del uso del ATX en cirugía de artroplastia de cadera y rodilla a dosis fijas de 2 gramos (g) intravenosos con dos pautas diferentes.

Material y métodosSe realiza un estudio de intervención prospectivo aleatorizado de 240 pacientes. Los pacientes fueron divididos en 3 grupos: 1) control; 2) administración de 1g de ATX intraoperatorio y otro postoperatorio; 3): 2g de ATX preoperatorios. Cada grupo consta de 40 pacientes intervenidos de artroplastia total de rodilla y otros 40 de cadera.

Se estudia la pérdida sanguínea postoperatoria, índice de transfusiones y la aparición de complicaciones tromboembólicas.

ResultadosSe obtienen diferencias estadísticamente significativas (p<0,05) en la pérdida sanguínea y transfusión entre grupo 1 y grupos 2 y 3, pero no entre grupos 2 y 3. Observamos una complicación en grupo 1 (trombosis venosa profunda).

DiscusiónSe realizó este estudio no para confirmar la eficacia del ATX, un hecho ya establecido, si no para confirmar si la pauta empírica de 2 g iv. es segura y qué pauta es más beneficiosa.

En conclusión podemos decir, coincidiendo con la literatura, que ambas pautas probadas de ATX son efectivas en la reducción de pérdida sanguínea y en las necesidades de transfusión sin aumentar el índice de complicaciones.

The loss of blood that occurs in total hip or knee replacement may lead to acute anaemia and therefore the risk of perioperative cardiovascular complications. Although the transfusion of red blood cells may prevent these complications, this has intrinsic risks such as infection, immunological reaction, the transmission of infectious diseases, acute lung damage, circulatory overload and increased associated costs.1–3 The percentage of cases in which transfusions are used in these surgical operations varies in the literature from 12% to 87%.3

One strategy to reduce blood loss and the risk involved in transfusion is the use of antifibrinolytic medication. Antifibrinolytic medicines inhibit the degradation of coagulation by interfering with the formation of plasmin through fibrinolysis and the dissolving of the incipient coagulation. Tranexamic acid (TXA) and e-aminocaproic acid are lysine analogue antifibrinolytic drugs that bind reversibly to plasmin as well as plasminogen.4

TXA is commercialised in Spain under the Amchafibrin® (Rottapharm, Italy) name. Its authorised indications for use are the treatment and prophylaxis of haemorrhages associated with excessive fibrinolysis, such as prostate and urinary tract surgical operations, gynaecological, thoracic, cardiovascular and abdominal surgery.5 The authorised indications for the use of TXA do not include orthopaedic and traumatological surgery.5 Nevertheless, according to the results of randomised controlled trials and systematic revisions, TXA administered during total hip and knee replacement surgery may prevent haemorrhaging, reducing intra- and postoperative blood loss by 20–50%.6–14 In fact, the updating of the consensus guide on alternatives to the transfusion of allogenic blood known as the “Seville Document”,15 suggests the use of TXA in orthopaedic surgery with a weak recommendation supported by high quality evidence (2A).

The ideal dose and regime to obtain the maximum benefit from TXA are unknown.16 The dose evaluated in the published studies for replacement surgery of the knee and hip varies from 10mg to 25mg (mg)/kilogramme (kg) in 1, 2 or 3 intravenous (IV) doses. To prevent errors in calculation and possible iatrogenic harm some authors recommend set IV doses at 1g to 2g TXA.5

Study objectives- 1.

To analyse the efficacy of the use of TXA in hip and knee surgery at fixed 2g intravenous doses in two different regimes (Regime 1: 1g IV intraoperative and 1g IV 3h afterwards; regime 2: 2g IV preoperative).

- 2.

To evaluate its safety by studying the possible appearance of thromboembolic or cardiac complications.

A prospective randomised study was performed. The study group consists of 240 patients (89 men and 151 women). The patients who were given TXA were divided at random into two groups of 80 patients each (group 2 and group 3). Group 2 were given 1g IV TXA intraoperatively and 1g IV 3h after surgery, and group 3 were given a single dose of 2g IV TXA 30min before surgery. These two groups were compared to a retrospective control group who were not given TXA (group 1). Each group consists of 40 patients operated for total knee replacement (TKR) and 40 patients operated for total hip replacement (THR).

The inclusion criteria were: (1) primary unilateral osteoarthritis of the knee and/or hip. The exclusion criteria were: (1) inflammatory or autoimmune disease; (2) blood coagulation disorders; (3) a history of thromboembolic disease; (4) severe anaemia (preoperative Hb <7mg/dl); (5) peripheral neuropathy; (6) malign tumour; (7) contraindication or intolerance of the administration of low molecular weight heparin or TXA; (8) a history of epilepsy or severe kidney failure, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate of <30mg albumin per g of creatinin in urine (9), patients with an ASA score of 4 or 5.17

Patient data was gathered confidentially 2 months after surgery, to determine:

- (1)

Red blood cell transfusion (the percentage of patients who had to be transfused).

- (2)

Blood loss in the first 48h after the operation.

- (3)

Adverse events during the first 60 days after the operation. The adverse events evaluated were death in connection with thromboembolic events, myocardial infarction (high troponin and a clinical correlation with myocardial ischaemia), a cerebrovascular accident (clinical symptoms with evidence of cerebral lesion in imaging tests), convulsions, pulmonary thromboembolism (a clinical diagnosis with positive images), deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (a clinical diagnosis with the presence of positive images), and acute kidney failure (a 50% increase of creatinin in the serum over the preoperative level).

The sample size was set on the basis of the main aim of the study. It was set to achieve a level of confidence of 95% and a precision of 3%.

The study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee and Pharmacy Commission. All of the patients in the study who were given TXA were informed and gave their informed consent.

The researchers undertook the study according to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. The study took place according to the protocol and complied with the regulations of Good Clinical Practice (GCP), as described in the ICH Regulations for good clinical practice.

Surgical procedureAll of the surgical operations were performed from July 2013 to September 2015 by the same surgical team, using the same surgical procedure and following a standardised technique. All of the patients received prophylactic antibiotics, commencing approximately half an hour before the incision was made in their skin.

In TKR a cemented prosthesis with rear stabilisation was used, with a standard anteromedial approach. All surgical operations were performed with an ischaemia sleeve, and this was withdrawn after bandaging. Drainage without vacuum was used in all cases, with an epidural catheter during 48h. For THR in all cases an uncemented prosthesis of the Corail type was used, with a posterolateral approach and repair of the joint capsule when closing, and drainage without vacuum during 48h.

Individual morbidity and the risk of surgery-associated mortality were evaluated by the ASA score.

Blood managementThe same blood conservation procedures were used for all of the patients. The patients were not included in a programme for the donation of autologous blood before surgery. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were withdrawn at least 48h before surgery, and antiplatelet drugs were withdrawn at least 7 days before surgery.

Postoperative protocolsPostoperative care included a multimodal pain control programme and postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis during 48h. The control programme did not include the administration of local infiltrations. Two 100mg doses of intravenous iron were administered in all of the groups on the first two days after the operation, after which 100mg of ferrous glycine sulphate (one tablet of Ferro Sanol, UCB Pharma, Madrid, Spain) was administered orally during 30 days.

The rehabilitation protocol consisted of patient mobilisation 24h after surgery. TKR patients were included in a physiotherapy programme of active and passive mobilisation the second day after the operation. All of the patients were allowed to completely load the operated limb with the protection of crutches during one month after the operation.

Pharmacological prophylaxis used for venous thromboembolism commenced on the day of surgery, 6–10h after closure of the wound. 3500 units (UI) of subcutaneous Bemiparin Sodium (Hibor, Rovi, Madrid, Spain) were used for TKR during 35 days. 3500UI of subcutaneous Bemiparin Sodium was administered for the first two day for THR, followed by 10mg per day of oral Rivaroxaban (Xarelto, Bayer, Lille, France) during 30 days.

Evaluation of blood loss and complications- (1)

Blood loss was determined by calculating on the basis of the hematocrit (Ht) using Gross's formula18: estimated blood loss=estimated volume of blood×(reduction in Ht/average Ht), where the reduction of Ht is the difference between the preoperative figure (at from 15 to 7 days prior to surgery) and the postoperative figure (24h after surgery). This haemogram was repeated 24h later in patients who presented Hb levels of from 9 to 10g/dl with clinical symptoms of haemodynamic instability, according to the guidelines of the American Society of Anaesthesiology.19 In this case, the second haemogram was used as the reference in the study to calculate blood loss as well as to indicate red blood cell transfusion.

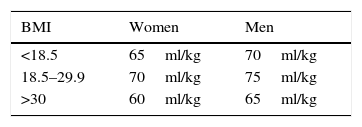

Gilcher's criteria20 were used to estimate the volume of blood of each patient (Table 1). The compensated blood loss was calculated by taking into account that a homologous unit of blood contains 150ml of red blood cells with 60% Ht.

Estimated volume of blood in adults according to Gilcher's criteria.

| BMI | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| <18.5 | 65ml/kg | 70ml/kg |

| 18.5–29.9 | 70ml/kg | 75ml/kg |

| >30 | 60ml/kg | 65ml/kg |

The criterion for blood transfusion was a level of Hb lower than 8g/dl in healthy patients without preoperative cardiopulmonary pathology, or a level lower than 9g/dl with clinical symptoms of haemodynamic instability.19

Clinical monitoring checked for the presence of DVT, using Doppler ultrasound scan of both legs when there was a clinical suspicion.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 22 programme, analysing an in-house database designed for this purpose. Quantitative variables are described by giving their average and interval of confidence at 95% when they are considered normal; qualitative variables are shown in percentage terms for each category.

The Student–Fisher t-test was used for the bivariant analysis of differences between the categories of a dichotomic variable compared with another quantitative one. Chi-squared was used to check the association between qualitative variables, and Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficient was used for the association between quantitative variables, or between a quantitative variable and an ordinal qualitative one.

For all comparisons the bilateral difference between groups was considered as the hypothesis, and the level of significance was set at 0.05.

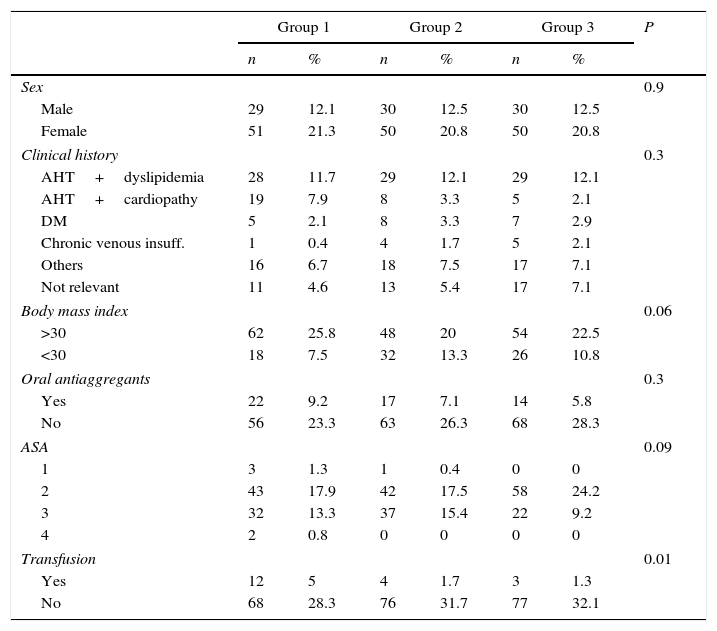

ResultsThe study group is composed of 89 men (37.1%) and 151 women (62.9%) with an average age of 72.7 (±8.7) years old. Table 2 shows the presence of preoperative comorbidity. Fifty three patients were taking antiaggregant medication (acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel) at home prior to surgery (22.1%).

Description of the sample.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | 0.9 | ||||||

| Male | 29 | 12.1 | 30 | 12.5 | 30 | 12.5 | |

| Female | 51 | 21.3 | 50 | 20.8 | 50 | 20.8 | |

| Clinical history | 0.3 | ||||||

| AHT+dyslipidemia | 28 | 11.7 | 29 | 12.1 | 29 | 12.1 | |

| AHT+cardiopathy | 19 | 7.9 | 8 | 3.3 | 5 | 2.1 | |

| DM | 5 | 2.1 | 8 | 3.3 | 7 | 2.9 | |

| Chronic venous insuff. | 1 | 0.4 | 4 | 1.7 | 5 | 2.1 | |

| Others | 16 | 6.7 | 18 | 7.5 | 17 | 7.1 | |

| Not relevant | 11 | 4.6 | 13 | 5.4 | 17 | 7.1 | |

| Body mass index | 0.06 | ||||||

| >30 | 62 | 25.8 | 48 | 20 | 54 | 22.5 | |

| <30 | 18 | 7.5 | 32 | 13.3 | 26 | 10.8 | |

| Oral antiaggregants | 0.3 | ||||||

| Yes | 22 | 9.2 | 17 | 7.1 | 14 | 5.8 | |

| No | 56 | 23.3 | 63 | 26.3 | 68 | 28.3 | |

| ASA | 0.09 | ||||||

| 1 | 3 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 43 | 17.9 | 42 | 17.5 | 58 | 24.2 | |

| 3 | 32 | 13.3 | 37 | 15.4 | 22 | 9.2 | |

| 4 | 2 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Transfusion | 0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 12 | 5 | 4 | 1.7 | 3 | 1.3 | |

| No | 68 | 28.3 | 76 | 31.7 | 77 | 32.1 | |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification system to estimate patient preoperative risk; DM: diabetes mellitus; AHT: arterial hypertension.

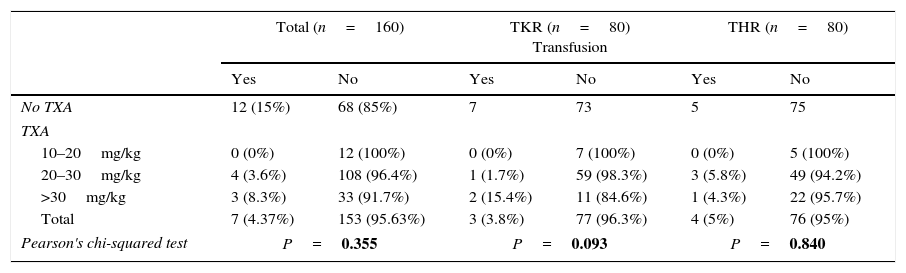

160 patients were administered 2g IV TXA. The average dose of TXA was 26.3 (±4.7) mg/kg bodyweight (range 12.4–38.4). In the majority of patients (112 patients – 70%) the average dose was from 20 to 30mg/kg; in 12 (7.5%) the average dose was 10–20mg/kg bodyweight, and in 36 patients (22.5%) it was from 30 to 38.5mg/kg. Divided according to sex, 60 men received 2g IV TXA, an average of 25 (±4.6)mg/kg, while the average for the women was 27 (±4.6)mg/kg. No statistically significant differences were found between these average doses of TXA and the transfusion rate (P>.05).

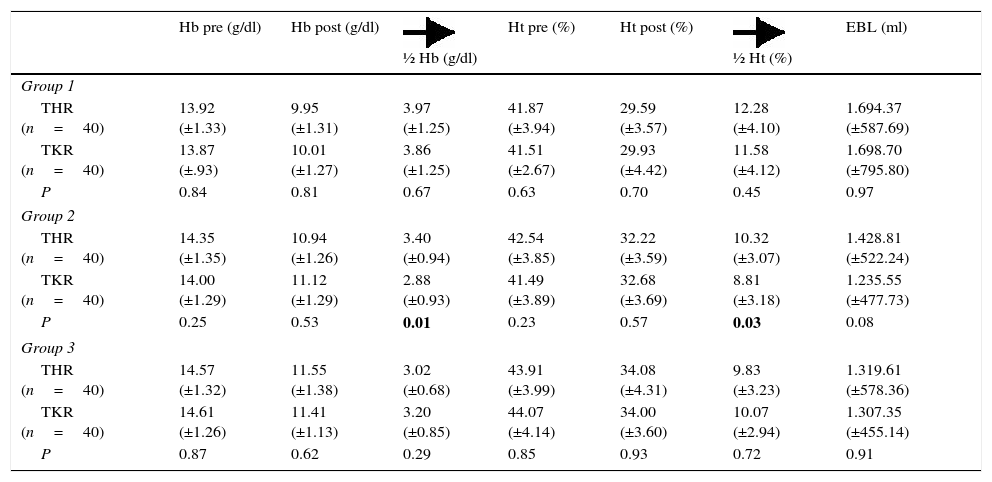

The average preoperative Hb in the sample was 14.2 (±1.2)mg/dl while the average preoperative Ht was 42.5 (±3.8). The average pre- and postoperative Hb and Ht in each group is shown in Table 3.

Average figures (±standard deviation) for preoperative haemoglobin, postoperative haemoglobin; average fall in haemoglobin; preoperative hematocrit, postoperative hematocrit; average fall in hematocrit and estimated blood loss, divided according to groups and type of surgery (THR and TKR).

| Hb pre (g/dl) | Hb post (g/dl) | ½ Hb (g/dl) | Ht pre (%) | Ht post (%) | ½ Ht (%) | EBL (ml) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | |||||||

| THR (n=40) | 13.92 (±1.33) | 9.95 (±1.31) | 3.97 (±1.25) | 41.87 (±3.94) | 29.59 (±3.57) | 12.28 (±4.10) | 1.694.37 (±587.69) |

| TKR (n=40) | 13.87 (±.93) | 10.01 (±1.27) | 3.86 (±1.25) | 41.51 (±2.67) | 29.93 (±4.42) | 11.58 (±4.12) | 1.698.70 (±795.80) |

| P | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.97 |

| Group 2 | |||||||

| THR (n=40) | 14.35 (±1.35) | 10.94 (±1.26) | 3.40 (±0.94) | 42.54 (±3.85) | 32.22 (±3.59) | 10.32 (±3.07) | 1.428.81 (±522.24) |

| TKR (n=40) | 14.00 (±1.29) | 11.12 (±1.29) | 2.88 (±0.93) | 41.49 (±3.89) | 32.68 (±3.69) | 8.81 (±3.18) | 1.235.55 (±477.73) |

| P | 0.25 | 0.53 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Group 3 | |||||||

| THR (n=40) | 14.57 (±1.32) | 11.55 (±1.38) | 3.02 (±0.68) | 43.91 (±3.99) | 34.08 (±4.31) | 9.83 (±3.23) | 1.319.61 (±578.36) |

| TKR (n=40) | 14.61 (±1.26) | 11.41 (±1.13) | 3.20 (±0.85) | 44.07 (±4.14) | 34.00 (±3.60) | 10.07 (±2.94) | 1.307.35 (±455.14) |

| P | 0.87 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.72 | 0.91 |

THR: total hip replacement; TKR: total knee replacement;

½ Hb: average fall in haemoglobin; ½ Ht: average fall in hematocrit; Hb pre: preoperative haemoglobin; Hb post: postoperative haemoglobin; Ht pre: preoperative hematocrit; Ht post: postoperative haematocrit; P: bilateral significance of Student's t-test for equality of measurements of the said figures comparing type of surgery (THR and TKR); EBL: estimated blood loss.Statistically significant P values are shown in bold type (P<.05).

The average reduction in Hb in the group 1 patients (the control group) was 3.9 (±1.2), while in group 2 it was 3.1 (±0.9) and in group 3 it was 3.1 (±0.7). The difference between group 1 and groups 2 and 3 was statistically significant (P=.00), while no statistically significant differences were found to exist between the average fall in Hb in group 2 and group 3 (P=.8). The average reduction in Ht in group 1 patients was 11.9 (±4.1), in group 2 it was 9.5 (±3.2) and in group 3 it was 9.9 (±3). The difference between group 1 and groups 2 and 3 was statistically significant (P=.00), while no statistically significant differences were found between group 2 and group 3 (P=.43).

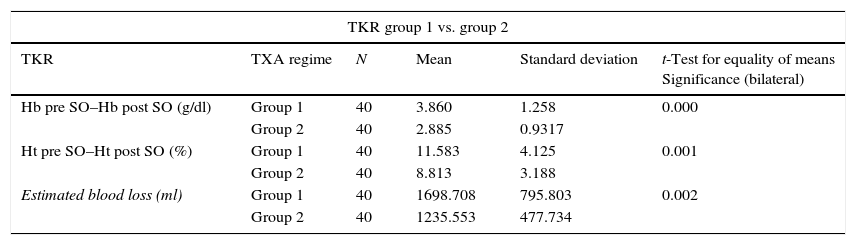

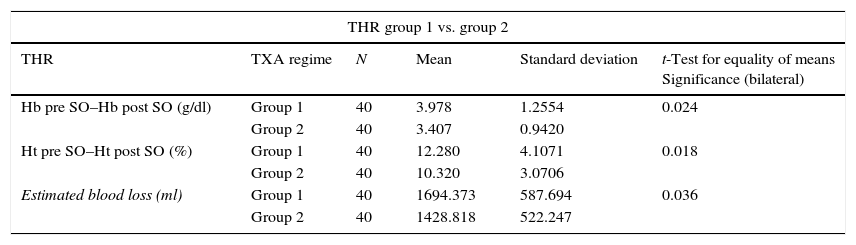

If the patients are divided according to type of surgery, the TKR patients showed statistically significant differences in terms of the average fall in Hb and Ht between group 1 and groups 2 and 3. Nevertheless, there are no statistically significant differences between group 1 and group 2 (P>.05). The same result is obtained for THR patients (Tables 4 and 5).

The relationship between the average fall in Hb and Ht and the TXA administration regime (groups 1, 2 and 3) in total knee arthroplasty.

| TKR group 1 vs. group 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKR | TXA regime | N | Mean | Standard deviation | t-Test for equality of means Significance (bilateral) |

| Hb pre SO–Hb post SO (g/dl) | Group 1 | 40 | 3.860 | 1.258 | 0.000 |

| Group 2 | 40 | 2.885 | 0.9317 | ||

| Ht pre SO–Ht post SO (%) | Group 1 | 40 | 11.583 | 4.125 | 0.001 |

| Group 2 | 40 | 8.813 | 3.188 | ||

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | Group 1 | 40 | 1698.708 | 795.803 | 0.002 |

| Group 2 | 40 | 1235.553 | 477.734 | ||

| TKR group 1 vs. group 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKR | TXA regime | N | Mean | Standard deviation | t-Test for equality of means Significance (bilateral) |

| Hb pre SO–Hb post SO (g/dl) | Group 1 | 40 | 3.860 | 1.258 | 0.008 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 3.205 | 0.854 | ||

| Ht pre SO–Ht post SO (%) | Group 1 | 40 | 11.583 | 4.125 | 0.044 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 10.075 | 2.941 | ||

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | Group 1 | 40 | 1698.708 | 795.803 | 0.009 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 1307.357 | 455.141 | ||

| TKR group 2 vs. group 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TKR | TXA regime | N | Mean | Standard deviation | t-Test for equality of means Significance (bilateral) |

| Hb pre SO–Hb post SO (g/dl) | Group 2 | 40 | 2.885 | 0.9317 | 0.113 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 3.205 | 0.8545 | ||

| Ht pre SO–Ht post SO (%) | Group 2 | 40 | 8.813 | 3.1889 | 0.070 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 10.075 | 2.9417 | ||

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | Group 2 | 40 | 1235.553 | 477.734 | 0.493 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 1307.357 | 455.141 | ||

TKR: total knee replacement; TXA: tranexamic acid; Hb: haemoglobin; Ht: hematocrit; pre SO: before surgery; post SO: after surgery.

The relationship between the average fall in Hb and Ht and the TXA administration regime (groups 1, 2 and 3) in total hip arthroplasty.

| THR group 1 vs. group 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THR | TXA regime | N | Mean | Standard deviation | t-Test for equality of means Significance (bilateral) |

| Hb pre SO–Hb post SO (g/dl) | Group 1 | 40 | 3.978 | 1.2554 | 0.024 |

| Group 2 | 40 | 3.407 | 0.9420 | ||

| Ht pre SO–Ht post SO (%) | Group 1 | 40 | 12.280 | 4.1071 | 0.018 |

| Group 2 | 40 | 10.320 | 3.0706 | ||

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | Group 1 | 40 | 1694.373 | 587.694 | 0.036 |

| Group 2 | 40 | 1428.818 | 522.247 | ||

| THR group 1 vs. group 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THR | TXA regime | N | Mean | Standard deviation | t-Test for equality of means Significance (bilateral) |

| Hb pre SO–Hb post SO (g/dl) | Group 1 | 40 | 3.978 | 1.2554 | 0.000 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 3.020 | 0.6888 | ||

| Ht pre SO–Ht post SO (%) | Group 1 | 40 | 12.280 | 4.1071 | 0.000 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 9.835 | 3.2321 | ||

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | Group 1 | 40 | 1694.373 | 587.694 | 0.005 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 1319.616 | 578.362 | ||

| THR group 2 vs. group 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THR | TXA regime | N | Mean | Standard deviation | t-Test for equality of means Significance (bilateral) |

| Hb pre SO–Hb post SO (g/dl) | Group 2 | 40 | 3.407 | 0.9420 | 0.069 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 3.020 | 0.6888 | ||

| Ht pre SO–Ht post SO (%) | Group 2 | 40 | 10.320 | 3.0706 | 0.493 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 9.835 | 3.2321 | ||

| Estimated blood loss (ml) | Group 2 | 40 | 1428.818 | 522.247 | 0.378 |

| Group 3 | 40 | 1319.616 | 578.362 | ||

THR: total hip replacement; TXA: tranexamic acid; pre SO: before surgery; post SO: after surgery.

There were also statistically significant differences (P=.00) in estimated blood loss between the group 1 patients (1,696.54±695.09ml) and those in group 2 (1,332.18±506.72ml) and group 3 (1,313.48±517.14ml); while no statistically significant differences were found between the two TXA administration regimes (groups 2 and 3) (P=.81). The same results were obtained when patients were divided according to type of surgery, in THR as well as in TKR (Tables 4 and 5). In THR there are statistically significant differences in blood loss between group 1 and group 2 (P=.03) and group 1 and group 3 (P=.00), although none were found between groups 2 and 3 (P=.37). In TKR statistically significant differences were also found between group 1 and groups 2 and 3 (P=.00 in both groups), although once again no statistically significant differences were found between the two regimes of TXA administration (groups 2 and 3) (P=.49).

When the average figures of Hb and Ht are compared in the groups according to type of surgery (Table 3), statistically significant differences are obtained in the average fall of Hb (P=.01) and Ht (P=.03) in group 2, although no statistically significant differences were found in terms of estimated blood loss (EBL). No statistically significant differences were found in the other groups for these parameters.

19 patients (7.9%) received red blood cell concentrate transfusions. Of these patients, 12 (15%) had not been given TXA (7 in THR and 5 in TKR); the other 7 (4.4%) had received TXA (4 patients in group 2 [2 in THR and 2 in TKR] and 3 in group 3 [2 in THR and one in TKR]). This difference in the administration or not of TXA was statistically significant (P<.05), while it was not significant for the two different regimes of TXA administration (groups 2 and 3). When the study centred on whether the dose of TXA administered (mg/kg bodyweight) influenced whether or not a transfusion was given, no statistically significant differences were found between the average dose given and divided by mg/kg bodyweight and the need for a transfusion (studied as a whole as well as classified by pathology) (P>.05) (Table 6).

The relationship between the dose of TXA and the percentage of transfusion (sample total and divided into TKR and THR).

| Total (n=160) | TKR (n=80) Transfusion | THR (n=80) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| No TXA | 12 (15%) | 68 (85%) | 7 | 73 | 5 | 75 |

| TXA | ||||||

| 10–20mg/kg | 0 (0%) | 12 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (100%) |

| 20–30mg/kg | 4 (3.6%) | 108 (96.4%) | 1 (1.7%) | 59 (98.3%) | 3 (5.8%) | 49 (94.2%) |

| >30mg/kg | 3 (8.3%) | 33 (91.7%) | 2 (15.4%) | 11 (84.6%) | 1 (4.3%) | 22 (95.7%) |

| Total | 7 (4.37%) | 153 (95.63%) | 3 (3.8%) | 77 (96.3%) | 4 (5%) | 76 (95%) |

| Pearson's chi-squared test | P=0.355 | P=0.093 | P=0.840 | |||

THR: total hip replacement; TKR: total knee replacement; TXA: tranexamic acid.

Statistically significant P values are shown in bold type (P<.05).

No relationship was found between body mass index and whether a transfusion was given. Nevertheless, a statistically significant relationship was found between the use of oral antiaggregants before the operation and transfusion (P<.005), when all of the patients were analysed together as well as when they were divided into THR and TKR.

A statistically significant difference was found between patients with Hb lower than 13g/dl prior to surgery and the transfusion rate (11 patients vs 8 patients transfused with preoperative Hb >13g/dl) (P=.000).

There was only one postoperative complication, a DVT in a patient who had not been given TXA.

DiscussionIn this work we agree with the published findings in the literature, as a statistically significant reduction was found in the postoperative reduction of Hb and Ht, in blood loss and in the percentage of blood transfusions (P=.000), without increasing the rate of thromboembolic complications with both TXA regimes used (groups 2 and 3) compared with the patients without TXA (group 1). This is so whether the sample as a whole was analysed, or when it was divided into THR and TKR patients.

This is not a new finding, given that the use of tranexamic acid in TKR and THR surgery to reduce blood loss and reduce the risk of transfusion has been properly studied and proven in the literature.6–14,21 In fact, the European Society of Anaesthesiology guide22 and the updated consensus guide on alternatives to allogenic blood transfusion, denominated the “Seville Document”15 suggest that TXA be used in orthopaedic surgery, with a weak recommendation supported by high quality evidence (2A). The evidence-based practical clinical guide by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons23 (April 2015) on the surgical treatment of arthrosis of the knee also concludes that there is strong scientific evidence for the fact that, in patients without any known contraindications, treatment with tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss and lessens the need for postoperative transfusions in total knee replacement operations.

Nevertheless, the majority of authors state that the ideal dose and regime for TXA to obtain the maximum benefit are still unknown.16 In the majority of published studies, the dose used in surgery of this type varies from 10mg/kg to 25mg/kg, although some authors recommend fixed IV doses of from 1 to 2g.5,12,24,25 In this study, and taking into account the results published in the literature as well as practical considerations, we used an empirical dose of 2g IV instead of using a weight-based dosage regime. The purpose of this was to check whether, in our population, this dose matched the weight-based doses recommended in the literature (10–25mg/kg bodyweight) as well as whether it was effective and safe (not increasing the rate of thromboembolic complications). Moreover, this regime, as Oremus el al.12 state, is a more accurate reflection of everyday clinical practice and leads to fewer errors in connection with dose calculation. According to the work of Ho and Ismail,8 in the majority of THR studies the total dose of TXA is lower than 30mg/kg, while in TKR studies higher doses were used. In our study, and adjusting the 2g TXA per patient weight, we found that in THR an average of 27.1 (±5)mg/kg was administered, while for TKR the corresponding figure was 25.5 (±4.2)mg/kg.

Many authors administer a loading dose prior to surgery (for THR) or during surgery (approximately 15min before deflating the tourniquet in TKR) and another repeat dose either by bolus or continuous infusion commencing 3h after the first dose,8,16 although many different administration regimes are described in the literature. Two different administration regimes were used in this work, with fixed 2g doses. These were in bolus form to facilitate the administration protocol for the medical team (nursing, anaesthesia and orthopaedic surgery staff). The resulting data show that both regimes are equally effective in reducing blood loss and the need for transfusion in TKR as well as in THR. No statistically significant differences were found between both regimes (P>.05). However, statistically significant differences must be taken into account in the average fall in Hb and Ht in group 2 when TKR is compared with THR (Table 3). Although they are completely different procedures and the fibrinolysis processes in these surgical procedures are dissimilar (so that they are not directly comparable), it must be remembered that the moment when TXA is administered to halt the fibrinolysis is influential. In fact, some authors16,26 recommend administering TXA at the start of the THR operation to make it more effective. Although no statistically significant differences were found in this study, the average reduction in Ht, Hb and blood loss in THR was less in group 3 (preoperative administration) than it was in group 2 (Table 5). Taking this into account together with the data in Table 3, we believe that it is preferable to use the regime of preoperative 2g TXA in this surgery.

Preoperative haemoglobin concentration has been said to be a strong predictor of perioperative transfusion, and this is often used to detect those patients at greatest risk.27,28 In agreement with this, we found that patients with a Hb level <13g/dl had a higher rate of transfusions (P=.000).

Other associated factors also influence perioperative blood loss. These include sex, age, the physical condition of the patient, hypertension, body mass index, coagulation factors and the type of anaesthesia and surgery.28,29 In our study we did not find that these factors were associated with blood loss. Nevertheless, the data obtained suggest that the previous use of antiaggregant medication is associated with a higher rate of transfusion (P<.05). After analysis 47.1% (25 patients) who had taken platelet antiaggregants were found to have had previous comorbidity of arterial hypertension (AHT) and cardiac pathology. 7 of these patients went on to receive transfusions. Although no direct association was found in the bibliography consulted, we believe that this association may be due to the fact that patients who took platelet antiaggregants had a higher probability of haemodynamic instability, making it more likely that they would be transfused.

Studies of anaemic patients subjected to major orthopaedic surgery have shown that the optimisation of their Hb before the operation with erythropoietin and iron may reduce the rates of transfusion.2 In our hospital iron is now administered intravenously before programmed surgical operations of this type. However, these patients were excluded from this study to avoid distortion.

This study has some limitations. One is that the control group was retrospective. We started using tranexamic acid in April 2014, by which time its efficacy in reducing blood loss in arthroplasties had been fully established. Our experience with TXA showed a reduction in postoperative blood loss and the number of transfusions that were necessary. This study was not conducted to confirm the efficacy of TXA, as this has already been established, but rather to confirm whether the empirical regime of 2g IV is safe, and which administration regime is the most beneficial. Secondly, DVT and TEP were diagnosed by clinical monitoring using imaging tests when there was a clinical suspicion.

However, one of strong points of this study is that the research took place with consecutive patients in a normal clinical environment, without the distortion of selection. Additionally, the groups in this study are highly homogenous, given that all of the procedures were carried out by the same surgical team using the same type of surgery, with similar implants. The perioperative medical procedures and postoperative measurements were also similar, as were the preoperative criteria and demographic variables. On the other hand, blood loss was calculated on the basis of the haematological parameters analysed in the same laboratory, using the blood samples collected at the same time during each procedure.

To conclude, in agreement with the literature we are able to say that in our study the empirical use of 2g IV TXA (without the need for adjustment according to patient weight) reduces the percentage of postoperative blood loss (according to the figures of Hb and Ht) without increasing the rate of thromboembolic or cardiac complications. No statistically significant differences were detected between the use of 2g IV 30min before surgery or dividing the dose into 1g intraoperative (15min before loosening the ischaemia sleeve in TKR) and another dose 3h later, although we believe that it is preferable to use preoperative administration in the case of THR.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that the procedures followed conform to the ethical norms of the committee for responsible human experimentation and are according to the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed the protocols of their centre of work and those governing the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this paper.

FinancingThis work has not received any financing or specific grant from any financing body in the public or private sector, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank Dr Antón Acevedo Prado for his help and collaboration in the execution of the statistical study.

Please cite this article as: Castro-Menéndez M, Pena-Paz S, Rocha-García F, Rodríguez-Casas N, Huici-Izco R, Montero-Viéites A. Eficacia de 2 gramos intravenosos de ácido tranexámico en la reducción del sangrado postoperatorio de la artroplastia total de cadera y rodilla. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2016;60:315–324.