Knee involvement of soft tissue sarcomas is rare and very difficult to treat. Reconstruction of the extensor mechanism of the knee is essential to restore the functionality. Functional outcome is compromised by poor soft tissue coverage, adjuvant local radiotherapy, and resection of the extensor apparatus. No results were found in the literature as regard treatment by resection and reconstruction of the extensor mechanism in combination with adjuvant radiotherapy. The effects of radiotherapy are also unknown in the allografts.

Material and methodTwo cases are presented of soft tissue sarcoma around the knee treated by resection, reconstruction of the extensor mechanism with cryopreserved cadaver allograft, and local radiotherapy.

ResultsAfter more than 3 years of follow-up, both patients are free of disease and have a good joint balance.

Discussion and conclusionsResection of the tumour with adequate safety margins and reconstruction using cadaveric allograft preserves the extensor mechanism and function of the limb. The soft tissue coverage is an added problem that can be solved by propeller fasciocutaneous flap coverage. After surgery, the limb must be immobilised with a knee brace locked in extension. Local radiotherapy contributes to local control of the disease. The reconstruction of the extensor mechanism of the knee with allograft is a functional alternative to amputation, and it does not contraindicate adjuvant radiotherapy to improve local control of the disease.

La afectación de la rodilla por sarcomas de partes blandas es rara y muy difícil de tratar. La reconstrucción del aparato extensor de la rodilla es fundamental para restaurar la funcionalidad. El resultado funcional está comprometido por la cobertura deficiente de tejidos blandos, la radioterapia local adyuvante y la resección del aparato extensor. No hemos encontrado literatura escrita del resultado del tratamiento mediante resección y reconstrucción del aparato extensor en combinación con radioterapia adyuvante, ni se conocen los efectos de la radioterapia en los homoinjertos.

Material y métodoPresentamos 2 casos clínicos de sarcoma de partes blandas del entorno de la rodilla tratados mediante resección, reconstrucción del aparato extensor mediante homoinjerto de cadáver criopreservado y posterior radioterapia local.

ResultadosTras más de 3 años de seguimiento ambos pacientes están libres de enfermedad y presentan buen balance articular.

Discusión y conclusionesLa resección del tumour con adecuados márgenes de seguridad y la reconstrucción mediante homoinjerto de cadáver permite preservar el mecanismo extensor y la funcionalidad. La cobertura de tejidos blandos es un problema añadido que puede solventarse mediante la cobertura con colgajo fasciocutáneo Propeller. Después de la cirugía la rodilla se ha de inmovilizar con una ortesis bloqueada en extensión. La radioterapia local contribuye al control local de la enfermedad. La reconstrucción del aparato extensor de la rodilla con homoinjerto es una alternativa funcional a la amputación, y no contraindica la radioterapia adyuvante para mejorar el control local de la enfermedad.

Soft tissue sarcomas (STS) are a heterogeneous group of tumours with a mesenchymal origin which grow in soft tissues providing connection, support and envelopment to noble organs or parenchymas. They can originate in connective, adipose, smooth or striated muscular, blood vessel or lymphatic tissue, and represent less than 1% of the total malignant tumours.1 Around 40% of them are located in the legs, generally in or around the knee.1

Knee involvement by STS is rare and very difficult to treat. Attempts to preserve the limb are carried out through wide resections3 and repair of the extensor apparatus,2,3 which occasionally leads to total replacement of the joint in order to achieve adequate resection margins.4 In any case, the functional result can be affected by the eventual need to resect the extensor apparatus, 2,5 a deficient soft tissue coverage and local radiotherapy, which is usually necessary. Reconstruction of the knee extensor apparatus after its sacrifice due to tumoral resection can be carried out through knee arthrodesis or through a repair with an extensor apparatus allograft (or homograft) or with a pedicled muscle flap (internal calf or gastrocnemius muscle). Another option is to carry out an extraarticular knee resection and subsequent reconstruction.5,6

As there are no references in the scientific literature regarding the results of radiotherapy on reconstructive allografts of the extensor apparatus, we present 2 clinical cases with over 3 years of follow-up.

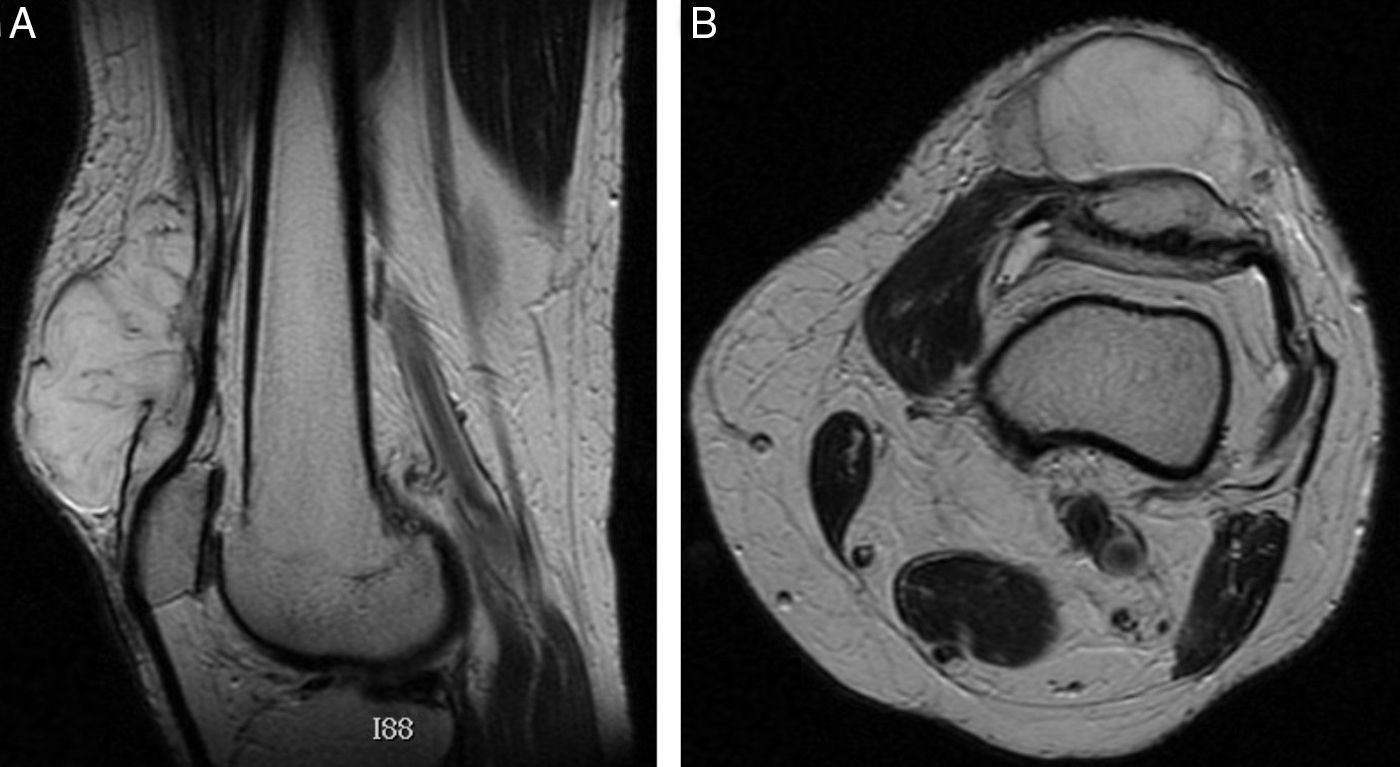

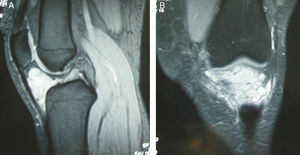

Case reportsCase 1The patient was a 69-year-old male who was referred due to a tumour in the anterior aspect of the left knee, proximal to the patella, with over 2 months evolution and not causing pain or functional limitation. Upon physical exploration, the tumour was not painful on palpation, was not adhered to deep planes and had a consistency between semisoft and solid. We obtained simple radiographs, ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, which revealed a lesion settled on the pre- and suprapatellar regions, measuring 94×57×95mm. It seemed to originate in the distal muscle-tendon union and infiltrate and separate the anterior fibres of the vastus medialis and the more superficial of the quadricipital tendon (Fig. 1A and B). We carried out a thoracic-abdominal-pelvic CT and closed CT-guided biopsy, which concluded with a diagnosis of stage III extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma according to the AJCC classification.

Under general anaesthesia and limb ischaemia, we conducted en bloc resection of the tumour on the anterior aspect of the knee, including the skin, quadricipital tendon, vastus medialis and, partially, the patellar ligaments, along with reconstruction with allograft from a cryopreserved cadaver (quadricipital tendon-patella-patellar tendon). The patellar tendon of the patient was reanchored to the patella of the allograft through transosseous suture, whilst the quadricipital tendon of the allograft was sutured to the rest of the quadriceps of the patient with Krakow-type stitches. The patellar tendons of the donor and receptor were sutured to each other. Lastly, the soft tissues were covered by a fasciocutaneous Propeller flap based on the saphenous and descending genicular arteries and a free skin graft from the anterior aspect of the ipsilateral thigh. The knee was immobilised through an orthosis blocked in extension, and the limb was maintained without load for 2 weeks. Partial progressive load was authorised after this period.

Once the diagnosis and wide resection margins were confirmed, 4 months after the intervention, we began 6MV photon radiotherapy on a surgical bed, fractioned into 200cGy per session, 5 times per week, up to 60Gy in the surgical bed, with a reduced margin after 50Gy. In total, the patient underwent 13 radiotherapy sessions.

The patient developed a slight humid radiodermatitis which improved with topical treatment, vein thrombosis of the left common femoral vein, partial tear of the inferior pole of the patella (Fig. 2), and haematogenous septic arthritis with an oral origin caused by Citrobacter koseri, 29 months after the intervention, which was treated through surgical debridement and antibiotic therapy for 6 weeks.

The joint balance of the knee 6 months after the cure was 10°–70° flexion (Fig. 3). There was no evidence of local or general disease recurrence 4 years after the intervention. At present, the patient presents slight pain, a slight limp and the functional result according to the Enneking scale or MSTS index for the lower limb is 66%.

Case 2The patient was a 29-year-old male with intermittent left gonalgia of 9 months of evolution, claudication upon standing and inability to kneel. Physical exploration found medial infrapatellar pain, with no signs of tumefaction or joint effusion. Knee exploratory manoeuvres resulted normal.

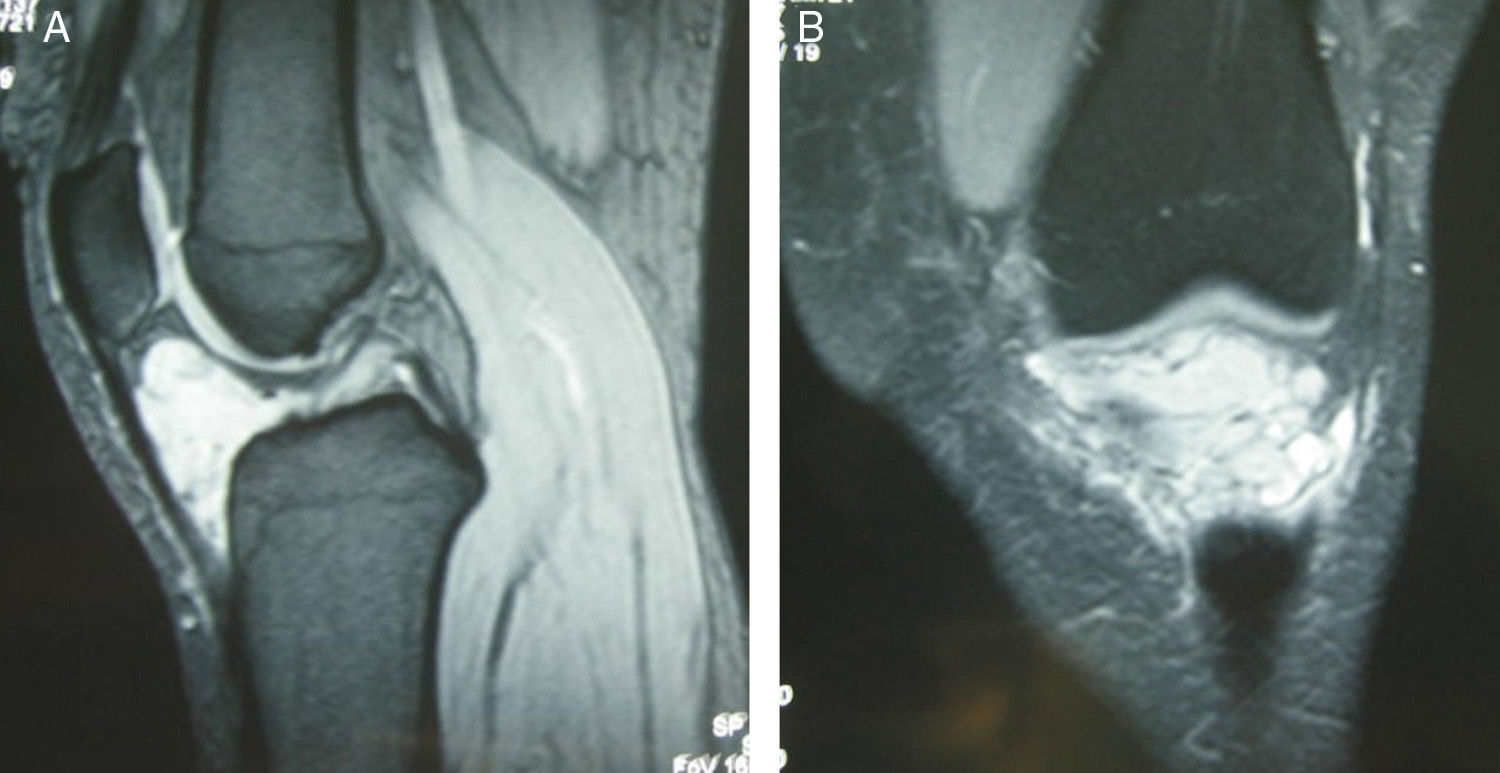

The patient underwent a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which identified a voluminous, multiseptated, cystic lesion with lobulated edges and a size of 5cm transverse diameter×4.5cm cranial-caudal diameter, in an infrapatellar position and occupying Hoffa fat. The lesion extended to the anterior aspect of the femorotibial compartments without causing bone involvement and was suggestive of corresponding to a synovial cystic lesion. It appeared less likely to be a synovial sarcoma, although this could not be ruled out (Fig. 4A and B).

The symptoms in outbreaks and the MRI scan suggested a synovial cyst as the most likely aetiology; however, due to the possibility of it being a malignant tumour, the interventionist radiology service carried out an ultrasound-guided FNA biopsy through a medial paratendinous approach. The biopsy established a histopathological diagnosis of the tumour as a synovial sarcoma with low grade malignancy, corresponding to a stage IA in the AJCC classification.

We requested an extension study through bone scintigraphy and thoracic-abdominal-pelvic CT scans. No lymph node or pulmonary metastases were identified.

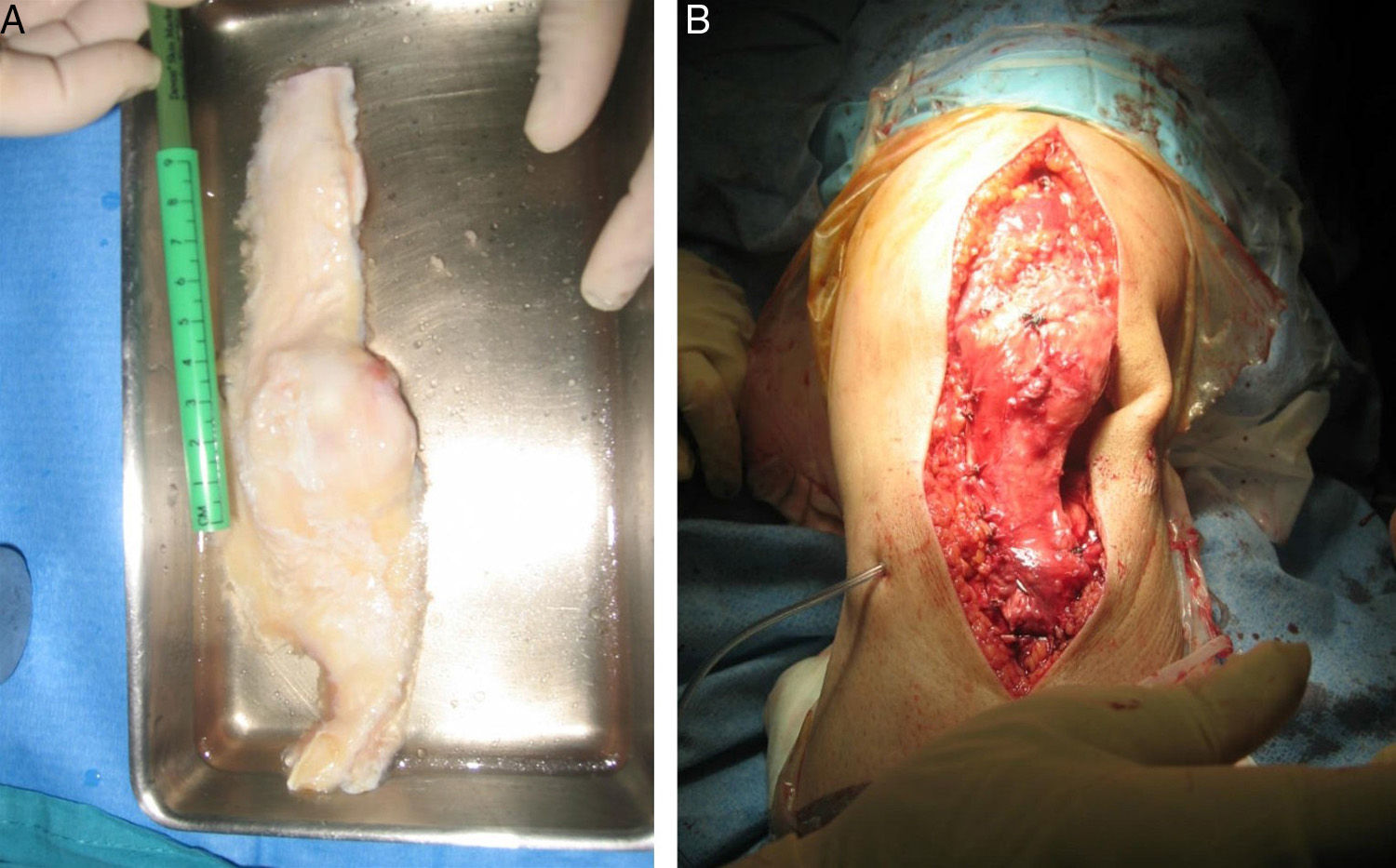

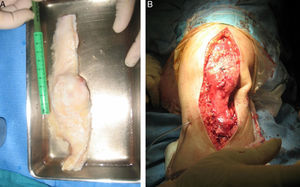

We conducted a midline longitudinal approach, resecting the biopsy area, and performed a wide resection of the tumour, including all the extensor apparatus (patella, patellar tendon, anterior tuberosity of the knee), anterior cruciate ligament, anterior portion of both menisci, along with a large bone fragment of the proximal tibial metaphysis.

Next, the defect was repaired through an allograft of the extensor apparatus from a cryopreserved cadaver (Fig. 5A), fixing the patellar tendon with a screw joined to the portion of the anterior tuberosity of the tibia from the allograft of the tibia of the patient (Fig. 5B) and suturing the quadricipital tendon of the allograft to that of the patient.

There were no complications in the postoperative period. The knee was immobilised with an orthosis blocked in extension, maintaining an unload period of 2 weeks.

Following a histological study of the surgical specimen, the tumour was catalogued as a biphasic synovial sarcoma with a low malignancy grade and measuring 4.5×4×3cm. It presented expansive nodular edges, located deep within Hoffa fat, with cystic areas and the presence of small, microscopic, satellite tumoural nodules close to the tumoural mass, which did not affect the surgical edges of the specimen or the lamina of the tibial bone.

One month after the surgical intervention, the patient started an adjuvant chemotherapy treatment, based on 4 cycles of ifosfamide-adriamycin.

One month and a half after the surgery, the patient was referred to rehabilitation for electrostimulation and to start active flexion-extension with an articulated knee support at 45° maximum flexion. The patient increased mobility with a joint balance of 5°–40° at 4.5 months, and 0°–115° at 15 months.

As complication, the patient developed synovitis after 15 months of the intervention and, at 32 months, a local recurrence in the subcutaneous cellular tissue, which was treated by wide resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy 2.5 months after the reintervention, up to a total dose of 60Gy. At present, 3.5 years later (5 since the first intervention), there is no evidence of new recurrences or metastasis. At the functional level, the patient reports very mild pain and can walk with a minimal limp, with knee mobility of 0°–130° and a functional result of 86% according to the MSTS classification (Fig. 6).

DiscussionThe treatment of choice in limb STS is limb rescue surgery,1,5,7 which is conducted in 70–85% of cases.8 Radiotherapy and advances in reconstruction techniques have reduced the incidence of amputations to 5% of patients.9

Preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy contributes to local control of STS. The combined treatment has local control rates of 90% or higher in STS.10

Reconstruction after knee resection can be performed by sacrificing joint mobility through an arthrodesis4 or preserving it. In the latter case, the extensor apparatus can be reconstructed using a cryopreserved allograft4,11 in the same way as a patella can be reconstructed with a vascularised flap from the internal calf or a transfer of fascia lata.11 When the extensor apparatus is sacrificed in the context of an en bloc extraarticular knee resection, then the reconstruction may be carried out through a megaprosthesis and/or osteoarticular allograft.6,7 In such cases, there are augmentation techniques that provide greater stability to the reconstruction, such as muscular flaps, tendon transfers and/or autografts or bone substitutes to reinforce the interface between the patellar tendon and the prosthesis.6,12

In our patients, we effectively reconstructed the extensor apparatus of the knee with a cryopreserved allograft. In comparison with other techniques, this is quick, scarcely aggressive and restores the functionality of the extensor apparatus10 enabling a more biological reconstruction.2 The drawbacks of this technique, compared to others, include a prolonged period of immobilisation with an orthosis13 and greater susceptibility to infections,14 with deep infection rates of up to 10% in cases of reconstruction after extensor apparatus tear following a total knee arthroplasty.15 In the long term, it could allow the development of femoropatellar arthrosis.14

Soft tissue coverage is an important key of this surgery to protect the allograft with healthy and well-vascularised muscle tissue and thus facilitate wound healing to prevent infection.14 The internal calf muscle flap provides good coverage.2,9,16 After the muscular transposition, it is possible to carry out cutaneous coverage of the flap with a skin flap to avoid necrosis of the adjacent skin.16

An immobilisation period of 6 weeks following the surgery, with the knee in extension, enables an optimal repair of the tendon. A good physiotherapy routine is essential to regain mobility and obtain a good functionality.16

Radiotherapy contributes to local disease control. Administered preoperatively, it is associated with higher infection rates, wound dehiscence and failures in muscular transposition. After the surgery it is associated to greater long-term fibrosis, oedema and joint rigidity.17 Up to 57% of patients suffer some rigidity, with contractures in 20% of cases, oedema in 19%, moderate to severe muscle strength decrease in 20% and fractures in between 4.6% and 7.6% of patients.18 A total of 7% required a cane or crutch in order to walk. When administering high doses in the presence of an allograft, this may experience physical and chemical changes, as well as alterations of biological quality19 and mechanical properties, with more fractures and infections.2 In a review of the scientific literature, the reconstruction of the knee extensor apparatus with an allograft has yielded good results,4,8,15 although function can become deteriorated over time due to contractures in flexion and failures of the allograft in up to 38% of cases.15

Postoperative radiotherapy did not cause any degenerative changes in the allograft among our patients and did not facilitate other complications, with joint function being maintained after a minimum period of 4 years. Thus, we consider that reconstruction of the knee extensor apparatus with an allograft is a functional alternative to amputation and that adjuvant radiotherapy is not contraindicated to improve local disease control.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work.

Conflict of interestAll authors certify that they have no financial or personal relationship with individuals or organisations that could represent a conflict of interests regarding the submitted article.

Please cite this article as: Illana-Mahiques M, Baixauli-García F, Angulo-Sánchez MA, Amaya-Valero JV, García-Forcada IL. Homoinjerto de aparato extensor y radioterapia en el tratamiento de sarcomas de partes blandas del entorno de la rodilla. A propósito de 2 casos clínicos. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:447–453.