Injuries of the medial epicondyle are relatively common, mostly affecting children between 7 and 15years. The anatomical characteristics of this apophysis can make diagnosis difficult in minimally displaced fractures. In a small percentage of cases, the fractured fragment may occupy the retroepitrochlear groove. The presence of dysesthesias in the territory of the ulnar nerve requires urgent open reduction of the incarcerated fragment. A case of a seven-year-old male patient is presented, who required surgical revision due to a displaced medial epicondyle fracture associated with ulnar nerve injury. A review of the literature is also made.

Las epifisiólisis de la epitróclea son lesiones relativamente frecuentes, que afectan fundamentalmente a niños entre los 7 y los 15 años. Las características anatómicas de esta apófisis puede dificultar el diagnóstico en las fracturas mínimamente desplazadas. En un pequeño porcentaje de casos el fragmento fracturario puede ocupar el surco retroepitroclear. La presencia de disestesias en el territorio del nervio cubital obliga a la reducción abierta urgente del fragmento incarcerado. Se presenta el caso de un paciente varón de 7 años de edad, que precisó de una revisión quirúrgica por una fractura desplazada de epitróclea asociada a lesión del nervio cubital. Se realiza una revisión de la literatura médica respecto a esta enfermedad.

Epiphysiolysis of the epitrochlea (or medial epicondyle) is a relatively common lesion, as this is the third most common fracture in children at the level of the elbow.1 These lesions are difficult to diagnose and require a high degree of clinical suspicion, especially in young children in whom the ossification center may not be visible on radiographs. Physical findings may vary depending on the degree of displacement of the medial epicondyle. Patients usually present the injured limb held next to the body with a flexed elbow, a very limited range of motion due to pain and tenderness upon palpation of the medial epicondyle which increases with valgus elbow mobilization. Neurological manifestations such as paresthesias or dysesthesias in the territory of the ulnar nerve are less frequent, especially when the epitrochlear fragment is significantly displaced.2,3

There is a lack of consensus regarding what degree of displacement would benefit from surgical treatment and whether cases with significant displacement should undergo a closed or open reduction. However, any dysesthesia or paralysis in the territory of the ulnar nerve is sufficient reason for exploration and revision of the nerve and reduction of the fragment.1,4

Case reportWe report the case of a 7-year-old boy who attended the emergency service due to severe pain in his right elbow after an accidental fall. Examination found limited mobility, widespread pain on palpation of bony prominences and absence of distal neurovascular injury. The radiographic study did not reveal any obvious injury, but due to clinical suspicion of an “occult fracture”, we applied an analgesic, posterior brachial splint indicating treatment with anti-inflammatories and review after 1 week to conduct an exploration once the acute phase of trauma had remitted.

During the following review we removed the splint and repeated the radiograph. We found no evidence of bone injury, but due to persistence of pain symptoms in the elbow we decided to place a new splint and conduct a review after a further 2 weeks.

During the evolution control at 3 weeks, the patient presented dysesthesias in the ulnar territory of the hand and fingers, with positive Froment sign and pain upon epitrochlear palpation, with very limited mobility.

The radiographic evolution study revealed a radiopaque image with medial paraolecranial bone characteristics, not observed in the initial radiographs, and suggestive of displacement secondary to epitrochlear epiphysiolysis, despite prior immobilization. When the study was completed with an urgent MRI, we observed a fragment of about 3.5mm diameter in the retroepitrochlear area relative to the ulnar nerve (Fig. 1).

(A) Initial anteroposterior radiograph of the elbow showing no evidence of lesion. (B) Initial lateral radiograph of the lesion. (C) Anteroposterior radiographic projection identifying a radiopaque image in the medial aspect of the condyle. (D) An MRI study confirms the occupation of the retroepitrochlear canal.

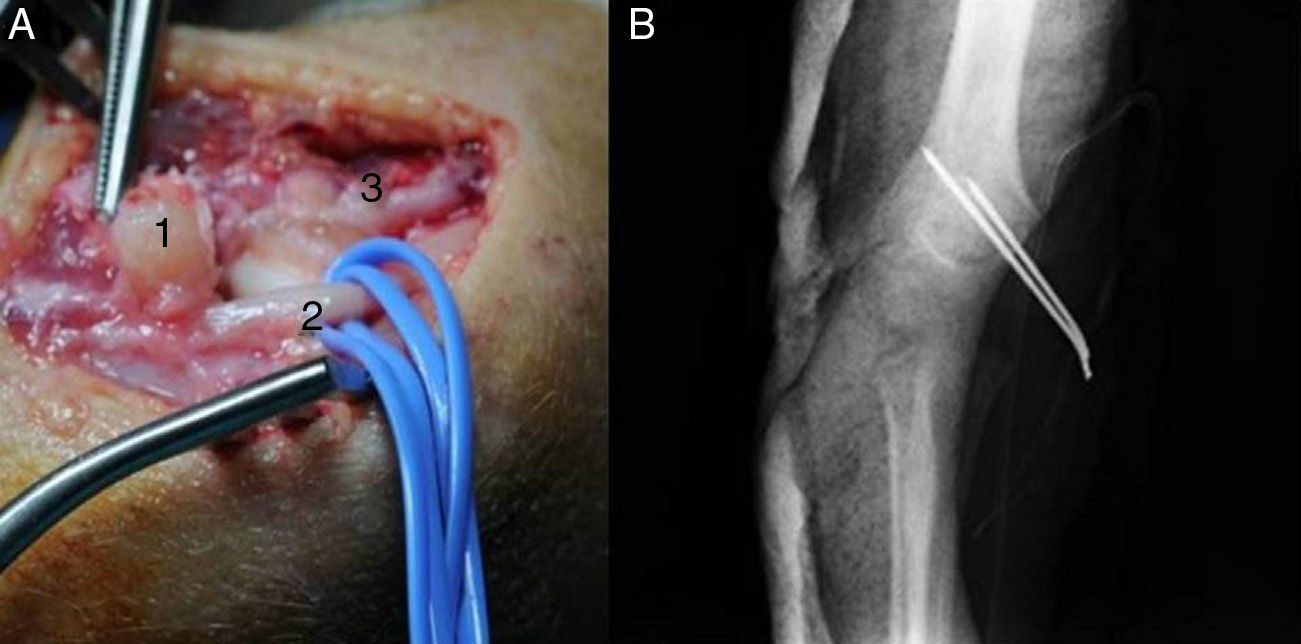

We opted for surgical revision under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, we identified severe extrinsic compression of the ulnar nerve by an osteocartilaginous fragment of the epitrochlea, which we fixed using 2 Kirchner wires of 1.8mm after curettage of the fracture site (Fig. 2). The patient was discharged at 48h with slight improvement of dysesthesias and we observed complete recovery over the course of 2 weeks. We maintained the patient with a posterior brachial splint for 5 weeks, when we proceeded to remove the Kirschner wires and started assisted, active and passive mobility exercises.

At 7 months of evolution after surgery, mobility was 145° flexion (155° on the contralateral side), with full extension of the elbow and no sequelae of ulnar nerve involvement after rehabilitation treatment.

DiscussionCases of epitrochlear epiphysiolysis generally occur between the ages of 7 and 15 years.4 They account for 10% of all physeal injuries in the elbow region, being the third kind in terms of frequency,1 after supracondylar and external condylar fractures.2

Medial epicondyle fractures are difficult to diagnose because the fracture is initiated through the cartilage, since the epitrochlea is not completely ossified until the age of 9 years. Therefore, their diagnosis requires a high level of clinical suspicion.3

The mechanism of injury is usually a trauma in forced valgus, caused by traction of the conjoined tendon of the flexor muscles which avulses the epitrochlea. It is associated with elbow dislocation in up to 60% of cases.1 In many cases, there is doubt regarding whether the fracture has taken place due to a spontaneously reduced, occult or partial elbow dislocation.

In a small percentage of cases, the epitrochlea may become displaced and incarcerated within the ulnohumeral joint due to the opening of the latter during valgus stress, thus injuring the nerve.2

The epitrochlea matures slowly, as it is the last ossification nucleus to join the humeral diaphysis. Its location, slightly posterior to the midline, can lead to confusion when interpreting radiographs. Confirmation of minimally displaced fractures can be facilitated by comparative projections of the contralateral elbow which determine the normal width of the cartilaginous space between the metaphysis and the medial epicondyle. Fragments trapped within the joint may be difficult to identify, especially in young patients with minimal ossification. Although widening of the medial space can be observed in anteroposterior radiographs, the only finding may be an eccentric relationship of the ulnohumeral joint in the lateral radiograph. Therefore, whenever a medial epicondyle fracture is suspected, it is imperative to obtain a strict profile of the elbow. Inability to obtain it should increase our suspicion of a trapped medial epicondylar fragment.

Computed tomography (CT) is the most accurate method for a correct assessment of displacement.1 Several studies have shown that fractures which were considered to be minimally displaced in radiographic studies showed up to 10mm displacement in CT studies. In such cases, the therapeutic approach was changed from conservative to surgical.1,5

There is consensus that non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures (less than 2mm) can be treated conservatively. This involves immobilization for at least 3 weeks, using a brachiopalmar cast in moderate flexion and with the forearm in pronation.6 Oblique radiographs and comparative radiographs of the healthy side can help to calculate the degree of displacement. Absolute indications for surgery include the presence of an incarcerated fragment within the joint or an open fracture.1 Reduction and osteosynthesis are indicated if the epitrochlea is displaced over 2mm, rotated or if the elbow is unstable with forced valgus. It is thought that the conservative treatment of displaced epitrochlear fractures can cause symptomatic valgus instability due to functional elongation of the ulnar collateral ligament. Therefore, surgery would be indicated.7,8

It is also unanimously accepted that intraarticular fragments should be removed. Although some authors warn of the risk of removal by closed techniques due to the possibility of damaging the ulnar nerve, others recommend making a gentle attempt in cases of sharp entrapment (less than 24h after the lesion). Extraction by closed manipulation is achieved by opening the joint with valgus stress and supinating the forearm with wrist and finger dorsiflexion, in order to contract the flexor muscles and extract the medial epicondylar apophysis from the joint. Other authors have suggested that electrical stimulation of the flexor mass or articular distension with saline solution could facilitate the extraction. Nevertheless, any attempts at closed reduction should be ruled out in the presence of neurological symptoms.

For this reason, open reduction and fixation with 2 Kirschner wires, a screw or reabsorbable nails or screws is often performed. The use of Kirschner wires is usually reserved for young patients with an open physis.4 Multiple authors emphasize the use of cannulated screws in order to obtain a stable fixation and thus allow early mobilization.1,4 After the treatment, the epitrochlear physis is normally closed. Since it does not contribute to longitudinal growth and is not articulated with the ulna, there are no problems related to growth arrest. Cases of epitrochlear avascular necrosis and nonunion associated to surgical treatment are usually asymptomatic.3

The main complication is failure to perform a correct diagnosis. Since stiffness is the most common complication in these lesions, an early diagnosis is important. This requires a high level of clinical suspicion, in order to avoid unnecessary immobilization periods. Pseudoarthrosis (or nonunion) of the fragment with respect to the distal metaphysis takes place in up to 50% of fractures with significant displacement, although this appears to be more of a radiographic than a functional problem. The percentage of nonunion is higher in cases treated orthopedically.1 Some studies indicate that there are no long-term differences regarding pain and ulnar nerve symptoms compared to surgical and orthopedic treatment.4

The incidence of ulnar nerve dysfunction in this type of fractures ranges between 10% and 15%,4 although it increases up to 50% if the fragment is trapped within the joint.

Any dysesthesia or paralysis in the ulnar nerve territory is sufficient reason for a surgical revision of the nerve and open reduction of the fragment.9 The need to transpose the ulnar nerve or not will depend on whether this is subluxated or not to anterior with flexion-extension of the elbow after the fracture is reduced, although it is not usually necessary.

Level of evidenceLevel de evidence iv.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that this investigation did not require experiments on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their workplace on the publication of patient data and that all patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare having obtained written informed consent from patients and/or subjects referred to in the work. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Moril-Peñalver L, Pellicer-Garcia V, Gutierrez-Carbonell P. Fractura incarcerada de epitróclea con lesión del nervio cubital. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:375–378.