To demonstrate the effectiveness of early weight bearing with no immobilisation (functional therapy) applied to fractures of the fifth metatarsal.

Materials and methodA retrospective case and control observational study was performed among 382 fractures on the fifth metatarsal comparing functional, conservative-orthopaedic and surgical treatments. Fractures were classified according to the settlement on the distal, diaphyseal or proximal part of the bone, the recommended therapy and the treatment performed. Influence of age, profession and characteristics of the injury were considered and results were measured using the parameters incapacity for work and number and intensity of complications.

DiscussionFractures of the fifth metatarsal are the most common injuries of the foot. Whether conservative or surgical treatment is recommended depends on the sort of fracture, the trend nowadays is to use non-invasive methods.

ConclusionsFunctional treatment for metatarsal fractures provides earlier healing and fewer adverse effects than conventional therapies, and becomes first choice for non-displaced fractures and most displaced fractures of the fifth metatarsal.

Comprobar la efectividad del tratamiento de las fracturas del quinto metatarsiano mediante la aplicación de la carga precoz del miembro afecto sin inmovilización (tratamiento funcional).

Material y métodoEstudio analítico observacional retrospectivo de casos y controles realizado sobre 382 fracturas del quinto metatarsiano en el que se compararon los resultados del tratamiento funcional con los tratamientos ortopédico y quirúrgico. Las fracturas se clasificaron en base a su localización distal, diafisaria o proximal, a la recomendación terapéutica y al tratamiento finalmente efectuado, y se estudió la influencia de las variables edad, actividad profesional y característica de cada fractura, evaluándose los resultados mediante la duración de la incapacidad temporal y el número y la gravedad de las complicaciones.

DiscusiónLas fracturas del quinto metatarsiano son las lesiones más frecuentes del pie. El tratamiento puede ser conservador o quirúrgico dependiendo de cada tipo de fractura, existiendo en la actualidad una tendencia a utilizar métodos no invasivos.

ConclusionesEl método funcional proporciona una curación más temprana, así como menos complicaciones y de menor gravedad que los tratamientos clásicos, siendo de primera elección en las fracturas sin desplazamiento de los fragmentos y en prácticamente todas las fracturas desplazadas del quinto metatarsiano.

Based on studies that have generically demonstrated the effectiveness of functional treatment of metatarsal fractures,1–3 we retrospectively studied the effects of the different existing treatments for fractures of the fifth metatarsal (functional, orthopaedic and surgical) and the influence of other variables that might affect the results.

The functional method consists of exerting early pressure with full load on the affected limb within the three weeks following the injury, with no bandage or immobilisation, just a flat-soled, post-operative shoe.

Given the hypothesis that this method for fractures of the fifth metatarsal is an alternative to conventional treatments, we decided to check its effectiveness comparing the results of the different metatarsal fracture treatments in terms of temporary disability and number and severity of complications, and to evaluate these results according to the type of fracture, age and occupation of the patients.

Materials and methodThis was a retrospective, observational, analytical case and control study performed on 382 patients who had suffered closed fractures of the fifth metatarsal between January 2004 and December 2012 in a mutual insurance hospital.

The case group comprised patients treated using the functional method (n=179), and the control group patients treated by immobilisation in a cast or another device and initial non-load-bearing (n=186), either by closed reduction with percutaneous needles or osteosynthesis with interfragmentary screws, cerclage wires or screwed plates (n=17).

Patients of both sexes were included in the sample, with no distinction as to race, aged between 16 and 65 years (in active employment), diagnosed with acute isolated or multiple closed fractures of the fifth metatarsal, displaced and undisplaced, articular and extra-articular, resulting in sick leave. Patients outside the 16–65 age range, and whose injuries were not closed and acute, diagnosed late or of onset exceeding 21 days were excluded from the study. Cases where there was a concomitance of conditions that might have masked or lengthened the process, and injuries that did not cause temporary disability were also excluded.

With a view to avoiding the typical errors of case and control studies,4,5 all the cases whose clinical histories contained inaccuracies or a lack of information were excluded from the study, and all the patients treated for metatarsal fractures in the hospital were included, except those who did not meet the inclusion criteria. All of the patients adhered to their treatment and none were lost to follow-up.

The patients attended by the author of this paper were treated using the functional method, irrespective of whether the traditional indication criteria recommended surgical traatment, while the remainder were treated by other doctors who opted indiscriminately for either the functional or conventional methods, depending on their clinical experience and confidence in the method.

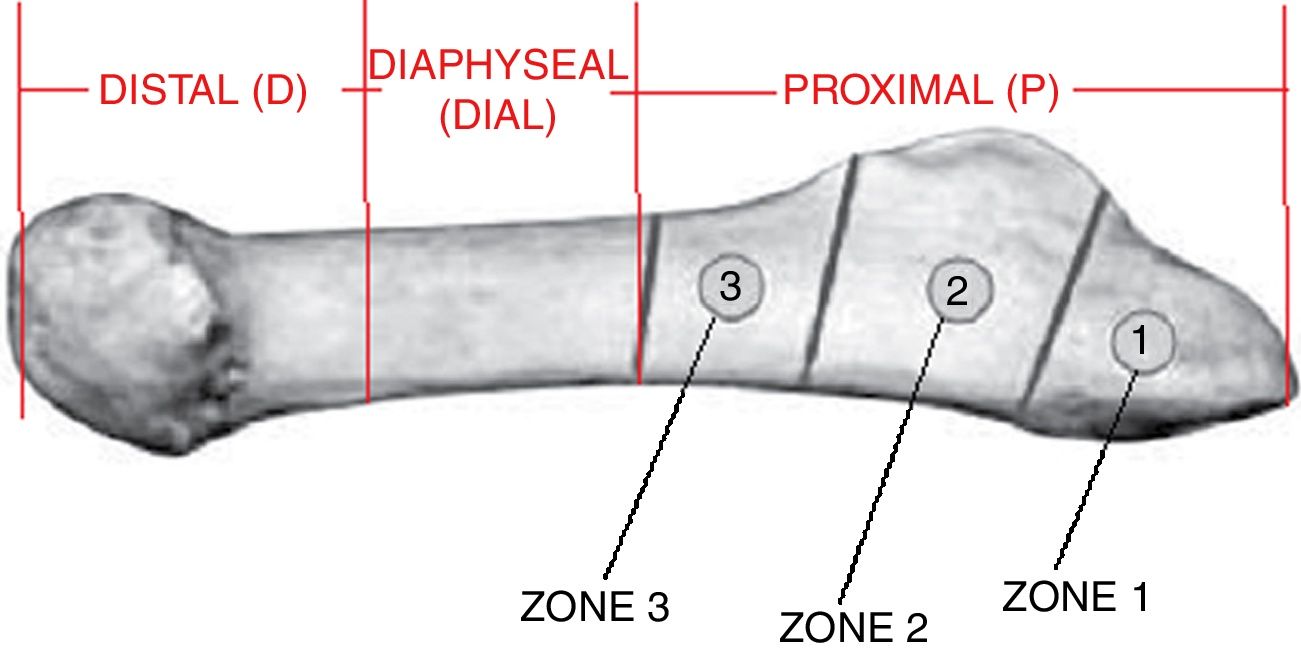

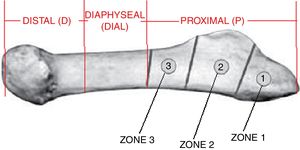

The fractures were classified based on the location of the fracture line (distal, diaphyseal or proximal in their different Dameron zones 1, 2 and 3) following the classification of the American Orthopaedic Trauma Association6 and that of Dameron and Lawrence-Botte,7,8 taking into account the degree of shortening, rotation or angulation of the fragments, showing the initial therapeutic indication as well as the treatment given (Fig. 1).

We took the classical recommendations of fragment diastasis, shortening, rotational deficit and angulation into account to establish suitable conservative or surgical treatment criteria.9–12

A series of parameters were studied to compare each treatment method:

- -

Independent variable: treatment given.

- -

Control variables: type of fracture, age and usual occupation characteristics.

- -

Result dependent variables: duration of temporary disability (TD) or sick leave, and complications of each treatment.

SPSS-22 for Windows13 was used for the statistical analysis.

Of the total sample of 382 individuals, 179 (46.85%) were treated with the functional method, 186 (48.70%) were treated orthopaedically, and 17 (4.45%) by surgery.

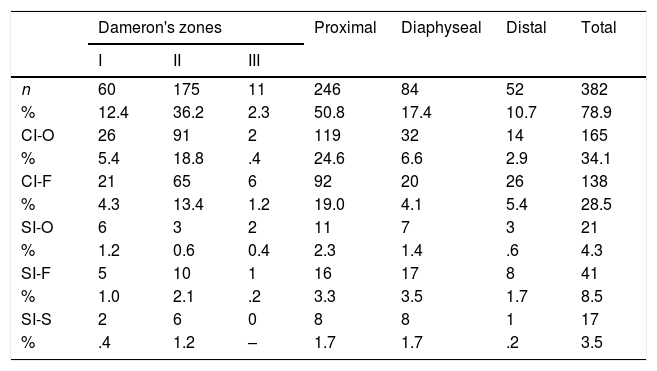

There was a total of 340 (89%) isolated fractures and 42 (11%) occurred in combination with one or more metatarsal fractures in the same foot (Table 1).

Overall sample composition. Fractures of the fifth metatarsal (n=382): number of cases and percentage of fractures according to the segment affected, therapeutic indication and treatment given.

| Dameron's zones | Proximal | Diaphyseal | Distal | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | |||||

| n | 60 | 175 | 11 | 246 | 84 | 52 | 382 |

| % | 12.4 | 36.2 | 2.3 | 50.8 | 17.4 | 10.7 | 78.9 |

| CI-O | 26 | 91 | 2 | 119 | 32 | 14 | 165 |

| % | 5.4 | 18.8 | .4 | 24.6 | 6.6 | 2.9 | 34.1 |

| CI-F | 21 | 65 | 6 | 92 | 20 | 26 | 138 |

| % | 4.3 | 13.4 | 1.2 | 19.0 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 28.5 |

| SI-O | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 21 |

| % | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 2.3 | 1.4 | .6 | 4.3 |

| SI-F | 5 | 10 | 1 | 16 | 17 | 8 | 41 |

| % | 1.0 | 2.1 | .2 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 8.5 |

| SI-S | 2 | 6 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 17 |

| % | .4 | 1.2 | – | 1.7 | 1.7 | .2 | 3.5 |

CI-F: conservative indication and functional treatment; CI-O: conservative indication and orthopaedic treatment; SI-F: surgical indication and functional treatment; SI-O: surgical indication and orthopaedic treatment; SI-S: surgical indication and surgical treatment; n: sample, number.

There were 303 (79.32%) undisplaced fractures compared to 79 (20.68%) with fragment displacement that indicated surgical treatment (Tables 1–3).

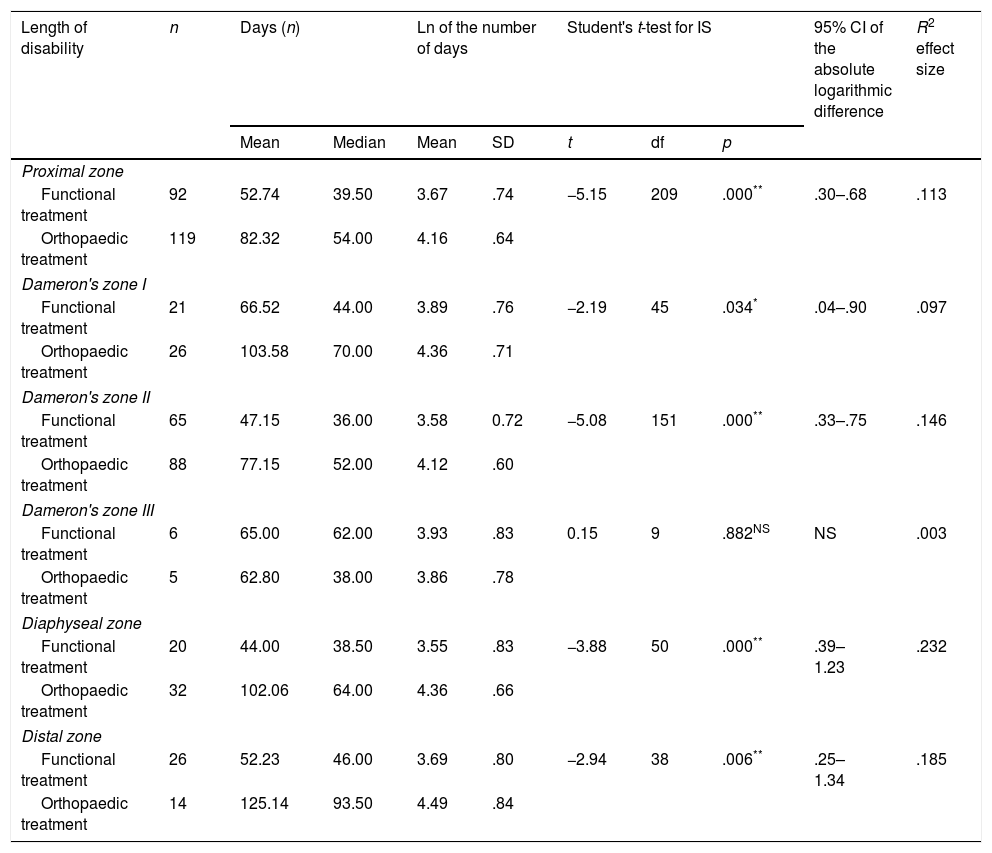

Means difference test. Length of temporary disability according to the type of treatment for fifth metatarsal fractures with conservative treatment indication (n=303).

| Length of disability | n | Days (n) | Ln of the number of days | Student's t-test for IS | 95% CI of the absolute logarithmic difference | R2 effect size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | SD | t | df | p | ||||

| Proximal zone | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 92 | 52.74 | 39.50 | 3.67 | .74 | −5.15 | 209 | .000** | .30–.68 | .113 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 119 | 82.32 | 54.00 | 4.16 | .64 | |||||

| Dameron's zone I | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 21 | 66.52 | 44.00 | 3.89 | .76 | −2.19 | 45 | .034* | .04–.90 | .097 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 26 | 103.58 | 70.00 | 4.36 | .71 | |||||

| Dameron's zone II | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 65 | 47.15 | 36.00 | 3.58 | 0.72 | −5.08 | 151 | .000** | .33–.75 | .146 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 88 | 77.15 | 52.00 | 4.12 | .60 | |||||

| Dameron's zone III | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 6 | 65.00 | 62.00 | 3.93 | .83 | 0.15 | 9 | .882NS | NS | .003 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 5 | 62.80 | 38.00 | 3.86 | .78 | |||||

| Diaphyseal zone | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 20 | 44.00 | 38.50 | 3.55 | .83 | −3.88 | 50 | .000** | .39–1.23 | .232 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 32 | 102.06 | 64.00 | 4.36 | .66 | |||||

| Distal zone | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 26 | 52.23 | 46.00 | 3.69 | .80 | −2.94 | 38 | .006** | .25–1.34 | .185 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 14 | 125.14 | 93.50 | 4.49 | .84 | |||||

NS: not significant (p>.05).

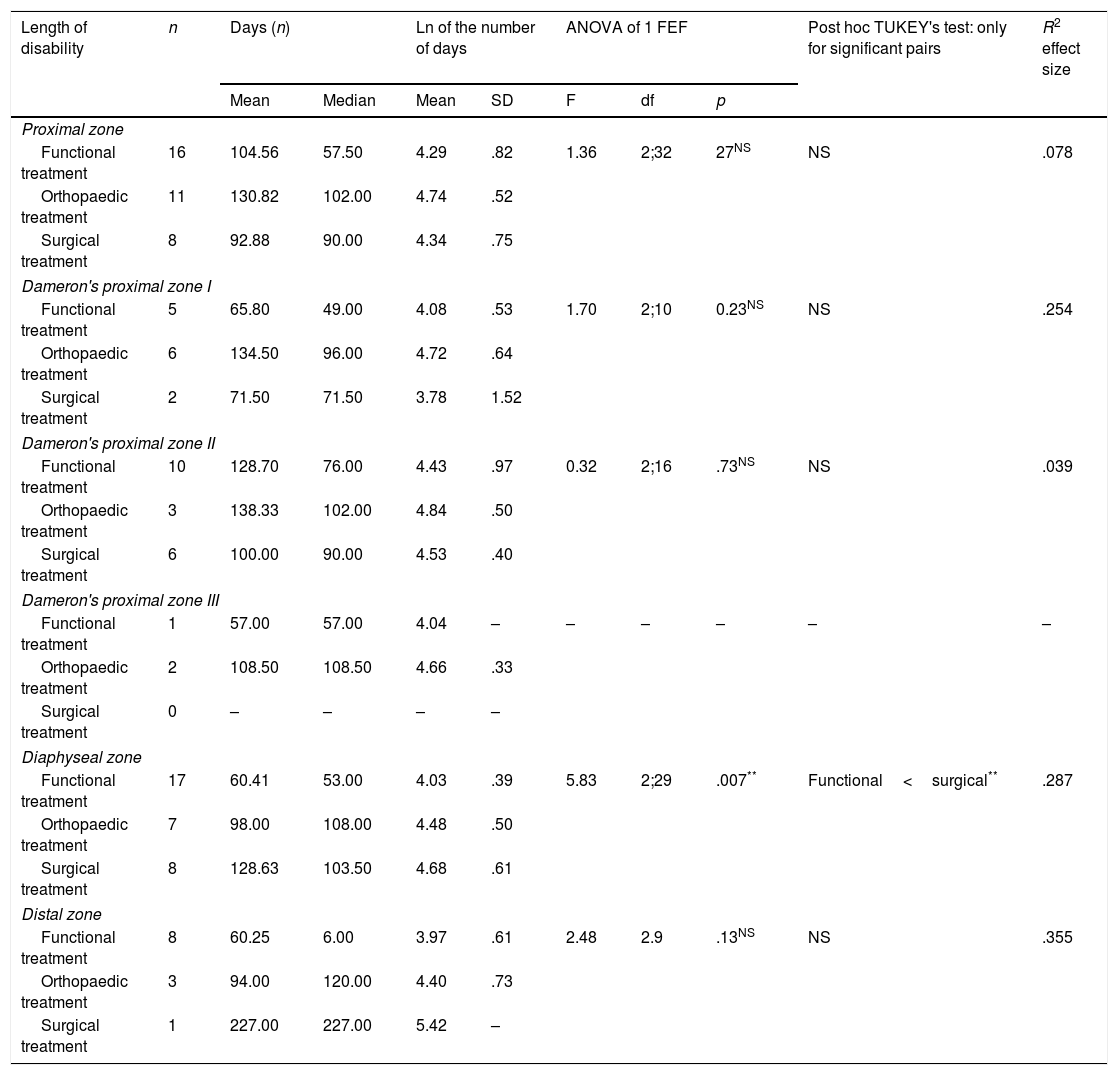

Means difference test. Length of temporary disability according to the type of treatment of fifth metatarsal fractures with surgical treatment indication (n=79).

| Length of disability | n | Days (n) | Ln of the number of days | ANOVA of 1 FEF | Post hoc TUKEY's test: only for significant pairs | R2 effect size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | SD | F | df | p | ||||

| Proximal zone | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 16 | 104.56 | 57.50 | 4.29 | .82 | 1.36 | 2;32 | 27NS | NS | .078 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 11 | 130.82 | 102.00 | 4.74 | .52 | |||||

| Surgical treatment | 8 | 92.88 | 90.00 | 4.34 | .75 | |||||

| Dameron's proximal zone I | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 5 | 65.80 | 49.00 | 4.08 | .53 | 1.70 | 2;10 | 0.23NS | NS | .254 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 6 | 134.50 | 96.00 | 4.72 | .64 | |||||

| Surgical treatment | 2 | 71.50 | 71.50 | 3.78 | 1.52 | |||||

| Dameron's proximal zone II | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 10 | 128.70 | 76.00 | 4.43 | .97 | 0.32 | 2;16 | .73NS | NS | .039 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 3 | 138.33 | 102.00 | 4.84 | .50 | |||||

| Surgical treatment | 6 | 100.00 | 90.00 | 4.53 | .40 | |||||

| Dameron's proximal zone III | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 1 | 57.00 | 57.00 | 4.04 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 2 | 108.50 | 108.50 | 4.66 | .33 | |||||

| Surgical treatment | 0 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Diaphyseal zone | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 17 | 60.41 | 53.00 | 4.03 | .39 | 5.83 | 2;29 | .007** | Functional<surgical** | .287 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 7 | 98.00 | 108.00 | 4.48 | .50 | |||||

| Surgical treatment | 8 | 128.63 | 103.50 | 4.68 | .61 | |||||

| Distal zone | ||||||||||

| Functional treatment | 8 | 60.25 | 6.00 | 3.97 | .61 | 2.48 | 2.9 | .13NS | NS | .355 |

| Orthopaedic treatment | 3 | 94.00 | 120.00 | 4.40 | .73 | |||||

| Surgical treatment | 1 | 227.00 | 227.00 | 5.42 | – | |||||

NS: not significant (p>.05).

With regard to professional activities, 66 (17.28%) patients were sedentary workers, 154 (40.31%) had to walk for long periods on flat terrain, and 153 (40.05%) were very often required to walk on uneven terrain. We did not know the employment activities of 9 (2.36%) cases, as this was not shown in their histories (Tables 4 and 5).

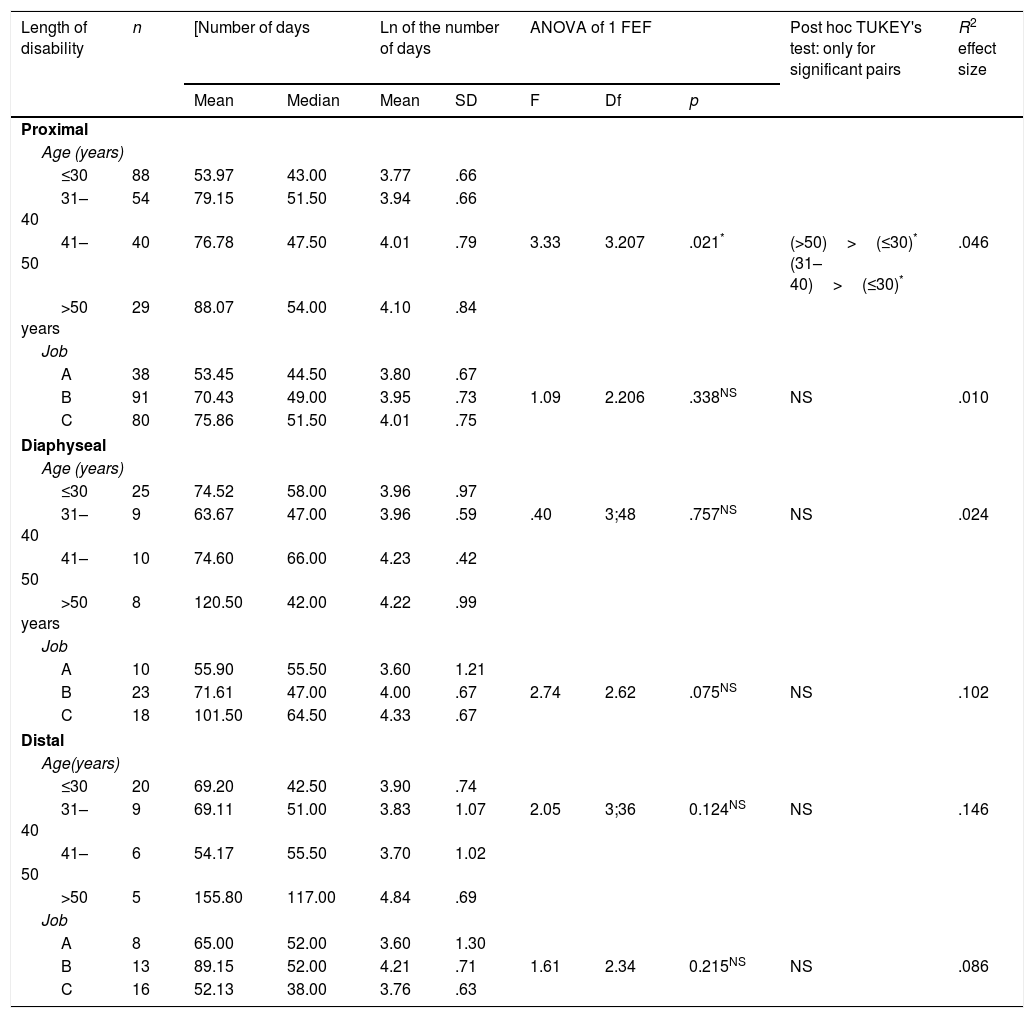

Means difference test. Influence of age and type of work on temporary disability in fifth metatarsal fractures with conservative treatment indication.

| Length of disability | n | [Number of days | Ln of the number of days | ANOVA of 1 FEF | Post hoc TUKEY's test: only for significant pairs | R2 effect size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | SD | F | Df | p | ||||

| Proximal | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤30 | 88 | 53.97 | 43.00 | 3.77 | .66 | |||||

| 31–40 | 54 | 79.15 | 51.50 | 3.94 | .66 | |||||

| 41–50 | 40 | 76.78 | 47.50 | 4.01 | .79 | 3.33 | 3.207 | .021* | (>50)>(≤30)* (31–40)>(≤30)* | .046 |

| >50 years | 29 | 88.07 | 54.00 | 4.10 | .84 | |||||

| Job | ||||||||||

| A | 38 | 53.45 | 44.50 | 3.80 | .67 | |||||

| B | 91 | 70.43 | 49.00 | 3.95 | .73 | 1.09 | 2.206 | .338NS | NS | .010 |

| C | 80 | 75.86 | 51.50 | 4.01 | .75 | |||||

| Diaphyseal | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤30 | 25 | 74.52 | 58.00 | 3.96 | .97 | |||||

| 31–40 | 9 | 63.67 | 47.00 | 3.96 | .59 | .40 | 3;48 | .757NS | NS | .024 |

| 41–50 | 10 | 74.60 | 66.00 | 4.23 | .42 | |||||

| >50 years | 8 | 120.50 | 42.00 | 4.22 | .99 | |||||

| Job | ||||||||||

| A | 10 | 55.90 | 55.50 | 3.60 | 1.21 | |||||

| B | 23 | 71.61 | 47.00 | 4.00 | .67 | 2.74 | 2.62 | .075NS | NS | .102 |

| C | 18 | 101.50 | 64.50 | 4.33 | .67 | |||||

| Distal | ||||||||||

| Age(years) | ||||||||||

| ≤30 | 20 | 69.20 | 42.50 | 3.90 | .74 | |||||

| 31–40 | 9 | 69.11 | 51.00 | 3.83 | 1.07 | 2.05 | 3;36 | 0.124NS | NS | .146 |

| 41–50 | 6 | 54.17 | 55.50 | 3.70 | 1.02 | |||||

| >50 | 5 | 155.80 | 117.00 | 4.84 | .69 | |||||

| Job | ||||||||||

| A | 8 | 65.00 | 52.00 | 3.60 | 1.30 | |||||

| B | 13 | 89.15 | 52.00 | 4.21 | .71 | 1.61 | 2.34 | 0.215NS | NS | .086 |

| C | 16 | 52.13 | 38.00 | 3.76 | .63 | |||||

NS: not significant (p>.05).

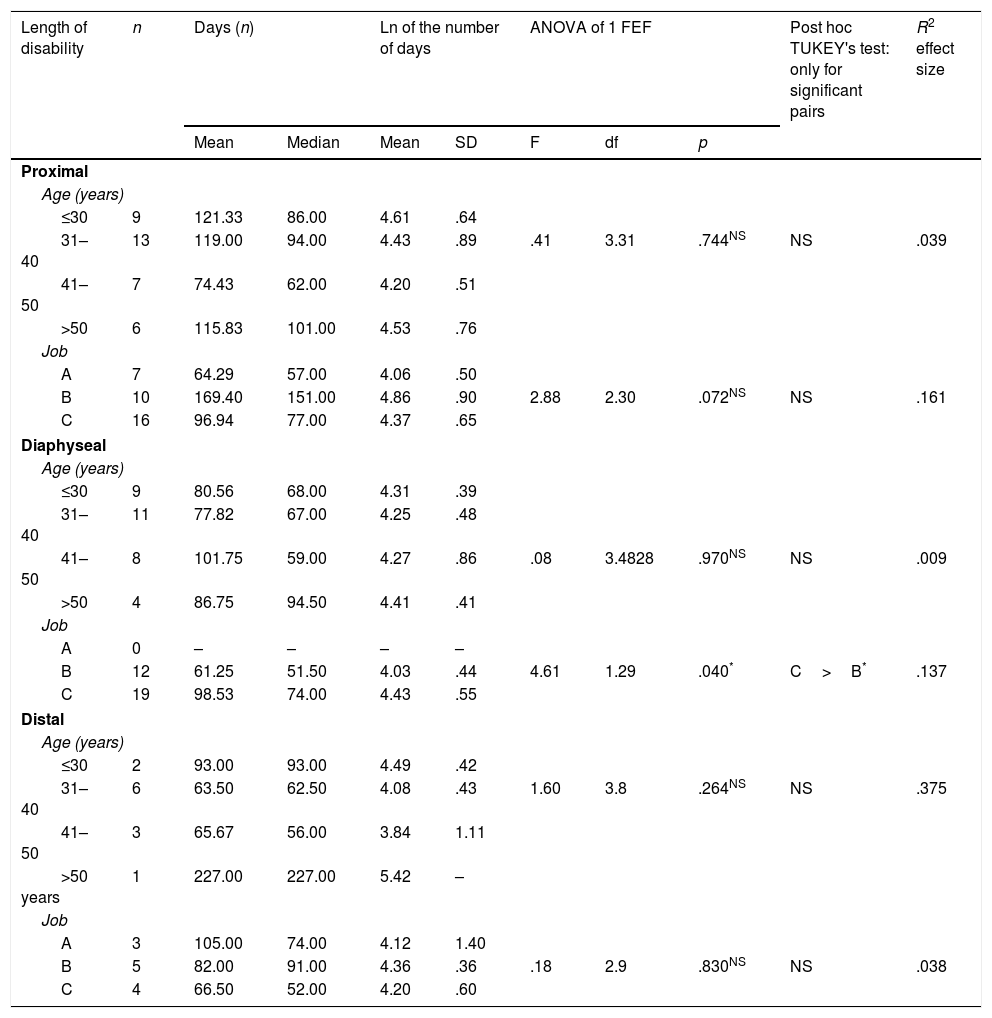

Means difference test. Influence of age and type of job on temporary disability in fifth metatarsal fractures with surgical treatment indication.

| Length of disability | n | Days (n) | Ln of the number of days | ANOVA of 1 FEF | Post hoc TUKEY's test: only for significant pairs | R2 effect size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | SD | F | df | p | ||||

| Proximal | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤30 | 9 | 121.33 | 86.00 | 4.61 | .64 | |||||

| 31–40 | 13 | 119.00 | 94.00 | 4.43 | .89 | .41 | 3.31 | .744NS | NS | .039 |

| 41–50 | 7 | 74.43 | 62.00 | 4.20 | .51 | |||||

| >50 | 6 | 115.83 | 101.00 | 4.53 | .76 | |||||

| Job | ||||||||||

| A | 7 | 64.29 | 57.00 | 4.06 | .50 | |||||

| B | 10 | 169.40 | 151.00 | 4.86 | .90 | 2.88 | 2.30 | .072NS | NS | .161 |

| C | 16 | 96.94 | 77.00 | 4.37 | .65 | |||||

| Diaphyseal | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤30 | 9 | 80.56 | 68.00 | 4.31 | .39 | |||||

| 31–40 | 11 | 77.82 | 67.00 | 4.25 | .48 | |||||

| 41–50 | 8 | 101.75 | 59.00 | 4.27 | .86 | .08 | 3.4828 | .970NS | NS | .009 |

| >50 | 4 | 86.75 | 94.50 | 4.41 | .41 | |||||

| Job | ||||||||||

| A | 0 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| B | 12 | 61.25 | 51.50 | 4.03 | .44 | 4.61 | 1.29 | .040* | C>B* | .137 |

| C | 19 | 98.53 | 74.00 | 4.43 | .55 | |||||

| Distal | ||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≤30 | 2 | 93.00 | 93.00 | 4.49 | .42 | |||||

| 31–40 | 6 | 63.50 | 62.50 | 4.08 | .43 | 1.60 | 3.8 | .264NS | NS | .375 |

| 41–50 | 3 | 65.67 | 56.00 | 3.84 | 1.11 | |||||

| >50 years | 1 | 227.00 | 227.00 | 5.42 | – | |||||

| Job | ||||||||||

| A | 3 | 105.00 | 74.00 | 4.12 | 1.40 | |||||

| B | 5 | 82.00 | 91.00 | 4.36 | .36 | .18 | 2.9 | .830NS | NS | .038 |

| C | 4 | 66.50 | 52.00 | 4.20 | .60 | |||||

NS: not significant (p>.05).

In terms of age, 153 (40.05%) patients were in the 16–30 age range, 102 (26.70%) patients were in the 31–40 age range, 74 (19.37%) were aged between 41 and 50, and a further 53 (13.88%) were injured aged between 50 and 65 years of age (Tables 4 and 5).

After the descriptive study of the sample, we performed a bivariate inferential analysis to compare the effect of the three potential treatments according to the initial indication or therapeutic recommendation depending on the length of temporary disability, using the Student's t-test and variance analysis (ANOVA), expressing the dependent variable in natural logarithms to adjust it to the normal curve model obtaining a mean of 4.08±.77, within a range of values 1.10–6.32, and median 4.03 within tolerable margins (As=−.02) with a slight deviation (Test KS: p=.018) in the goodness-of-fit test, linked to the high number of cases of the total distribution. The R2 coefficient value was used to express the effect size in the means contrast tests, which is an indicator of the magnitude of the changes observed in the dependent variable due to the influence of the manipulated independent variable, whose high value implies that the existing differences have a high level of confidence and can be appreciated almost at a glance even with very small samples.14

Finally, we performed a multivariate inferential analysis studying the modulatory/regulatory or distortive effect of the treatment method variables, age and job type, on the duration of temporary disability.

Three groups of professional activity were formed according to the requirements of each occupation. (A: sedentary work; B: jobs involving long periods of standing and walking on level terrain, and C: professions that require walking on uneven terrain.)

In order to study the influence of age, we chose to create a variable with four categories with cut-off points in tens, i.e., patients aged up to 30 years, from 31 to 40 years, between 41 and 50 years, and those aged over 51 years.

The variance analysis test was used to contrast the dependent variable (TD) with age and job, and to establish the effect of the factor contrasted after eliminating the contaminating effects of other variables, we used the covariance analysis (ANCOVA).

ResultsA sample of 382 patients with fractures of the fifth metatarsal was obtained, of whom 303 met the conservative treatment criteria, while surgical treatment was indicated for 79.

Of the 303 undisplaced fractures, 165 were treated by non-load-bearing, immobilisation in a cast and later functional rehabilitation, and 138 were treated functionally by early support using a rigid-soled shoe. On comparing the different treatments, performed in the bivariate analysis, generically a mean of the duration of temporary disability of 51.38 days was obtained for the patients treated with the functional method, compared to 89.78 days for those who were treated orthopaedically, with a 51.38 days for the patients treated by the functional method, compared to 89.78 days for those treated orthopaedically, with a p=.001 and R2=.138 (mild-moderate). On studying the effect of each treatment according to the location of the fracture, a shorter duration of temporary disability was observed in all the cases with very significant differences and moderate/high effect size in the diaphyseal, distal fractures and in the Dameron zone 2 fractures (Table 2).

Of the cases with displaced fractures that met the criteria for surgical treatment, 14 were operated while 35 were treated using the functional method. On comparing the effect of the treatments, generically a mean duration of temporary disability of 77.61 days was obtained for the patients who received functional treatment, an average of 114.62 days for those who received orthopaedic treatment, and a mean disability of 117.59 days for those who were operated, with a p=.006 and R2=.128. In the segmental study the significance was lost in the proximal and distal zone due to the small size of the sample, but the differences were maintained in the diaphyseal fractures (p=.007) with a high effect size (R2=.287) (Table 3).

After applying the multivariate study, we found that the differences between the treatments found in the bivariate study were maintained, and the mean number of temporary disability days was higher for the older patients, and in the jobs with high demands (Tables 4 and 5).

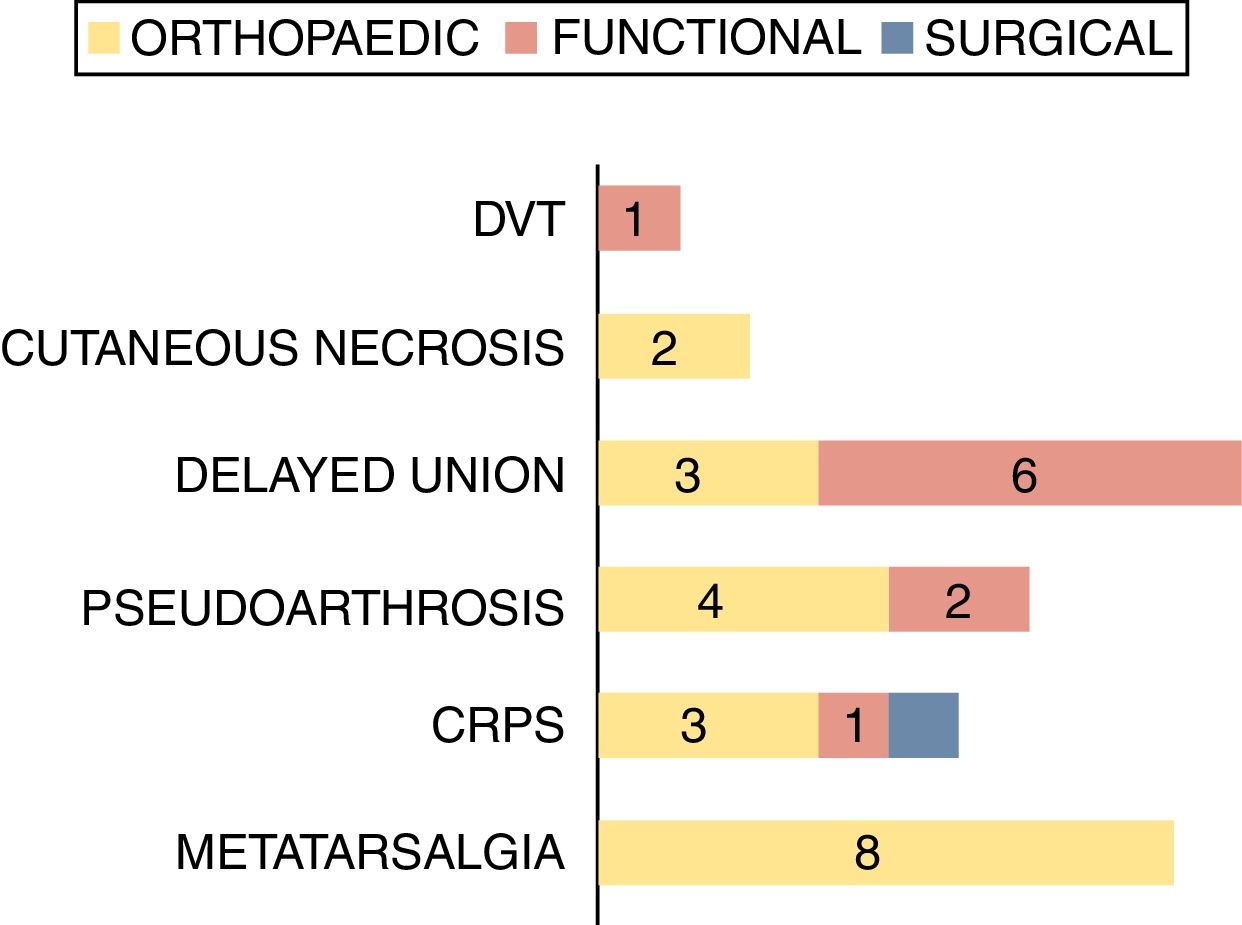

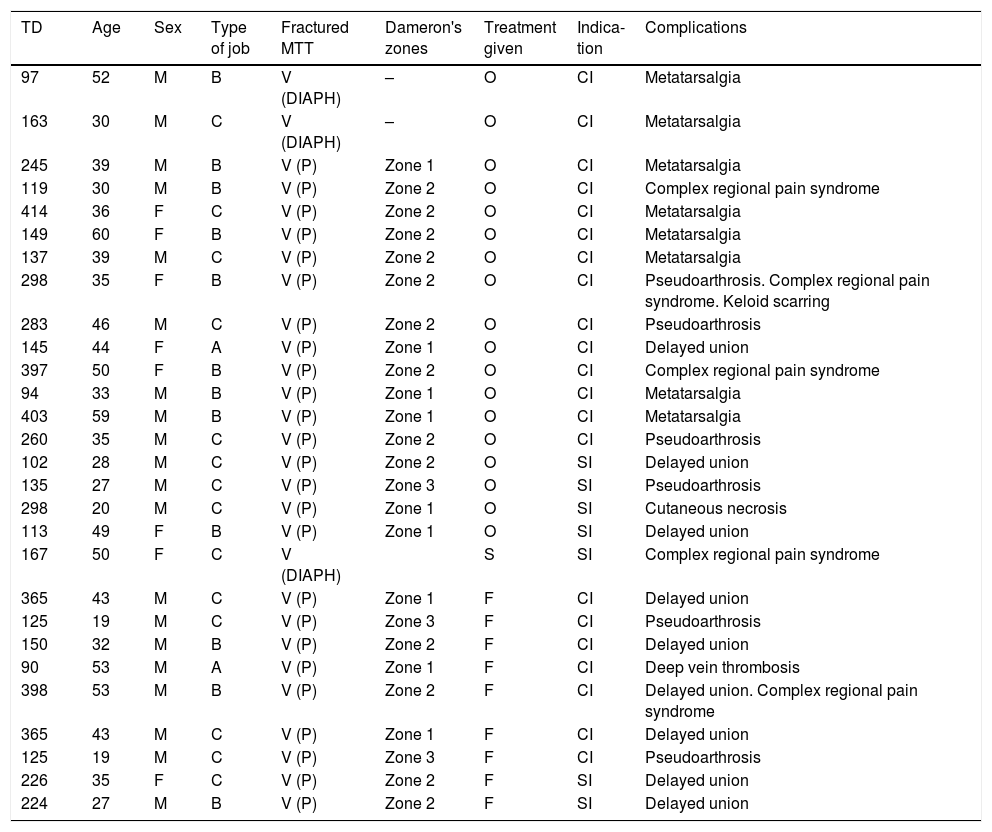

To homogenise and give greater validity to the results, we collected the complications of the isolated fractures of the fifth metatarsal and studied them from both a qualitative and a quantitative perspective, collecting all the circumstances that contributed to lengthening the processes beyond the average days of temporary disability plus two standard deviations (X+2DE) in each of the treatment methods. Each method was studied separately because we considered that they behave differently in terms of action mechanism and physiological basis.

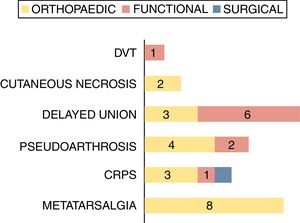

Thus, in the fractures that were treated with the functional method, complications were found in the processes that involved a disability of (X+2DE) 62.31 days, whereas this was 126.21 days for the surgical treatment, and 93.21 days for the fractures treated with a cast, (Fig. 2, Table 6).

Complications of isolated fractures of the fifth metatarsal.

| TD | Age | Sex | Type of job | Fractured MTT | Dameron's zones | Treatment given | Indica-tion | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97 | 52 | M | B | V (DIAPH) | – | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 163 | 30 | M | C | V (DIAPH) | – | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 245 | 39 | M | B | V (P) | Zone 1 | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 119 | 30 | M | B | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Complex regional pain syndrome |

| 414 | 36 | F | C | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 149 | 60 | F | B | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 137 | 39 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 298 | 35 | F | B | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Pseudoarthrosis. Complex regional pain syndrome. Keloid scarring |

| 283 | 46 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Pseudoarthrosis |

| 145 | 44 | F | A | V (P) | Zone 1 | O | CI | Delayed union |

| 397 | 50 | F | B | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Complex regional pain syndrome |

| 94 | 33 | M | B | V (P) | Zone 1 | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 403 | 59 | M | B | V (P) | Zone 1 | O | CI | Metatarsalgia |

| 260 | 35 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | CI | Pseudoarthrosis |

| 102 | 28 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 2 | O | SI | Delayed union |

| 135 | 27 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 3 | O | SI | Pseudoarthrosis |

| 298 | 20 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 1 | O | SI | Cutaneous necrosis |

| 113 | 49 | F | B | V (P) | Zone 1 | O | SI | Delayed union |

| 167 | 50 | F | C | V (DIAPH) | S | SI | Complex regional pain syndrome | |

| 365 | 43 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 1 | F | CI | Delayed union |

| 125 | 19 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 3 | F | CI | Pseudoarthrosis |

| 150 | 32 | M | B | V (P) | Zone 2 | F | CI | Delayed union |

| 90 | 53 | M | A | V (P) | Zone 1 | F | CI | Deep vein thrombosis |

| 398 | 53 | M | B | V (P) | Zone 2 | F | CI | Delayed union. Complex regional pain syndrome |

| 365 | 43 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 1 | F | CI | Delayed union |

| 125 | 19 | M | C | V (P) | Zone 3 | F | CI | Pseudoarthrosis |

| 226 | 35 | F | C | V (P) | Zone 2 | F | SI | Delayed union |

| 224 | 27 | M | B | V (P) | Zone 2 | F | SI | Delayed union |

A: sedentary job; C: job that requires walking on uneven terrain; F: Functional treatment; CI: conservative treatment indication; SI: Surgical treatment indication; TD: days of temporary disability; M: male; MTT: metatarsal; O: Orthopaedic treatment; S: Surgical treatment; V(D): distal fractures of the fifth metatarsal; V(DIAPH): diaphyseal fractures of the fifth metatarsal; V(P): proximal fractures of the fifth metatarsal.

With an incidence of 67 per 100,000 inhabitants per year, fractures of the metatarsal are the most common injuries to the foot.15 Seventy percent affect the fifth metatarsal, of which almost 80% occur to the proximal portion.16 Historically, due importance has not been attached to the diagnosis of these injuries, their treatment has occasionally been neglected17 and therefore they can result in painful sequelae that affect standing and gait.

The most appropriate treatment for metatarsal fractures has been and remains contraversial, particularly certain types of fractures where, due to their characteristics, location or onset, the lines between conservative and surgical treatment become blurred. In recent decades, the trend has been towards early functional therapy that avoids immobilisation and non-load-bearing of the limb.18

Depending on the type and characteristics of each injury, the traditional management of metatarsal fractures is either orthopaedic-conservative treatment by immobilisation and non-load-bearing over a variable period of time, or surgical reduction and stabilisation when there is angulation greater than 10 degrees, displacement greater than 3–4mm or head deviation in central metatarsal fractures and diaphyseal and distal fractures of the fifth metatarsal, for fractures of the first metatarsal with instability (displacement on manipulation and/or on X-rays weight bearing and under stress), displacement of the base, rotational deficits and shortening and increased transversal diameter in distal fractures, and in displaced fractures of the fifth metatarsal base (Fig. 3), and in undisplaced fractures with a symptomatic prodrome which might constitute chronicity or non-union.9–12

Both treatments, conservative and surgical, are routinely complemented with subsequent functional rehabilitation aimed at reducing inflammation and oedema, recovering joint and muscle balance and normalising standing and gait.19

Most authors agree that, generically, diaphyseal fractures of the central metatarsal with angulation greater than 10 degrees or more than 3mm to 4mm of displacement in the dorsal/plantar plane, and fractures with appreciable deviation of the metatarsal head should be reduced. Shortening is relatively tolerable and can be treated by immobilisation or with a hard sole and progressive weight-bearing.9–12 With fractures of the first metatarsal, conservative fractures is reserved for undisplaced fractures, with no loss of bone length and no evidence of instability on weight-bearing X-rays or stress views.9

Although some fifth metatarsal fractures have a high capacity for union, many others progress to non-union.20 To date, there is still controversy regarding fractures of the proximal portion of the fifth metatarsal in terms of their classification, diagnosis and treatment, which to a greater or lesser extent is due to the use of incorrect anatomical terms and the indiscriminate use of eponyms such as Jones’ fracture.7,21–26 Most are treated conservatively with tubular elastic bandages, cast or gradual weight bearing with support shoes27 and, as a general rule, if there is no displacement of fragments, distal zone fractures and proximal zone 1 Dameron's fractures can be treated orthopaedically with these conservative methods, whereas the treatment of zone 2 fractures is more controversial and varies depending on whether there are prodrome symptoms (short period of pain in subjects who were active before diagnosis). The initial treatment for acute fractures is rest with a plaster boot for a period of 8 to 10 weeks, and it is recommended that evolved fractures should be treated in the same way as those of zone 3, which often progress to non-union and therefore require more aggressive treatment.9 For these fractures that settle in zone 2 treatment can be started by immobilisation in a cast and non-weight-bearing for at least 3 months, although surgical treatment with graft and internal compression is also indicated, especially for athletes or professional sportspeople.28

Although to date this has been the standard indication for treating metatarsal fractures, a considerable number of studies question the traditional focus.1,9–11,29–35

The trend appears to have increased in recent years to treat metatarsal fractures conservatively. The latest editions of Rockwood's book include the possibility of treating fifth metatarsal fractures without displacement using the functional method.9 Polzer argues that this treatment is the most appropriate for Torg's zone 1 and 2 fractures,33 although does not recommend it for zone 3 fractures. Aynardi advocates treatment with casts and the functional method rather than surgery as the therapeutic option for acute, spiroid and displaced diaphyseal metaphyseal fractures of the fifth metatarsal34 (Fig. 4), and Shahid recommends treatment with weight-bearing using a walking boot for avulsion fractures of the base of the fifth metatarsal, since it results in earlier healing than immobilisation in a cast and non-weight-bearing.35 Renobales and collaborators advise the functional method for all metatarsal fractures irrespective of the zone affected and degree of displacement.2,3

The patients included in the study were studied respectively, which makes it impossible to perform clinical and radiological follow-up. We sought to avoid potential selection biases by selecting all the patients treated with metatarsal fractures in the centre, apart from those who did not meet the inclusion criteria. To prevent information biases, we made a detailed classification of the fractures based on the radiological data, and any patients whose clinical histories contained innaccurate clinical data, a lack of radiological studies or non-specific diagnosis and treatment were excluded.

When we proceeded to analyse the fractures according to the zone of settlement, the size of the subgroups studied was not homogenous. However, applying the R2 coefficient (effect size) together with the p value enabled us to reach conclusions with small sample sizes.

To conclude, functional treatment of metatarsal fractures, applied to closed fractures of the fifth metatarsal resulted in a shorter duration of temporary disability, and fewer and less serious complications than conventional treatments.

In fractures with no displacement of the fifth metatarsal, the disability time was shorter with functional treatment than with immobilisation in a cast when they settled in Dameron's distal, diaphyseal and proximal zones 1 and 2 (although in the isolated fracture group significance was lost in zone 1), and in displaced fractures, the duration of disability was shorter with functional treatment than with surgery. The difference was significant in the study of diaphyseal fractures but lost significance in fractures of the proximal and distal segments.

There is a tendency for fractures to heal earlier in younger patients and those with sedentary jobs.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Úbeda-Pérez de Heredia I. El apoyo inicial sin inmovilización como terapia de elección en las fracturas del quinto metatarsiano. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:348–358.