Perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) is a cell type constantly present in a group of tumours including angiomyolipoma (AML), clear-cell “sugar” tumour (CCST) of the lung and extrapulmonary sites, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), and clear-cell tumours of other anatomical sites. It has morphologic distinctive features: epithelioid appearance with a clear to granular cytoplasm, a round to oval, centrally located nucleus and an inconspicuous nucleolus. Immunohistochemically, PEC expresses myogenic and melanocytic markers. Eleven cases of primary bone PEComa presentation have been described since 2002.

ObjectiveTo report a case of primary bone perivascular epithelioid cell tumour.

Case report24 year-old male presented with pain. X-ray revealed an osteolytic lesion at right proximal tibia with soft tissue extension. Evaluation of slides identified a bony perivascular epithelioid cell tumour without immunohistochemical study confirmation.

ResultsPatient was treated by surgical excision and adjuvant chemotherapy (epirubicin/cysplatin). After two years of follow-up the patient remains disease free.

ConclusionsThis is the first-case report in Latin America. Immunohistochemical stains were negative and we believe it may be due to non-described ethnic variations.

La célula perivascular epiteloide (PEC) es un tipo celular constante presente en un grupo de tumores que incluyen el angiomiolipoma, tumores «de azúcar» de células claras pulmonares y de sitios extrapulmonares, linfangioleiomiomatosis, entre otros. Las características de la PEC incluyen: apariencia epiteloide con citoplasma claro agranular, un núcleo central redondo a oval y un nucléolo discreto además de expresar marcadores inmunohistoquímicos únicos. Únicamente han sido descritos 11 casos de presentación ósea primaria desde su primer reporte en 2002.

ObjetivoPresentar el caso de un tumor de células perivasculares epiteloides óseo primario.

Reporte de casoVarón de 24 años de edad con dolor de un año de evolución y lesión lítica de tibia proximal derecha y extensión a partes blandas. Diagnóstico histológico de tumor de células perivasculares epiteloides óseo e inmunohistoquímica negativa.

ResultadosSeguimiento de 2 años después del tratamiento con quimioterapia adyuvante (epirrubicina/cisplatino) y de la resección en bloque; el paciente se encuentra libre de enfermedad.

ConclusionesEste es el primer caso de tumor de células perivasculares epiteloides óseo primario reportado en Latinoamérica. No encontramos los marcadores inmunohistoquímicos y creemos que esto puede deberse a variaciones étnicas no descritas.

Perivascular epithelioid cell (PEC) is a cell type constantly present in a group of tumours which includes angiomyolipoma (AML), clear-cell “sugar” tumour (CCST) of the lung and extrapulmonary sites, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), melanocytic clear-cell tumour of falciform ligament and round ligament and rare clear-cell tumours of other anatomical sites.1

PECs were first described by Apitz in 19432; and Masson reported them as “abnormal myoblasts” in renal AML in his book.3 However, the term perivascular epitheloid cell was termed by Bonetti et al. in reference to epitheloid lesions with clear/acidophyl cytoplasm and perivascular distribution.4

The distinctive characteristics of the PEC include the epitheloid appearance with clear nongranular cytoplasm, a round to oval central nucleus and discreet nucleolus. This expresses myogenic and melanocytic immunohistochemical markers including HMB45, HMSA-1, MelanA/Mart 1, Mitf, actin and rarely desmin and they are associated with tuberous sclerosis. Doubts exist regarding the histogenesis of the perivascular epitheloid cell tumour of epitheloid AML definition and the identification of histological malignancy criteria.1,5

The World health Organisation has defined the perivascular epithelioid cell tumour (PEComa) as a “mesenchimatous tumour composed of perivascular epitheloid cells with distinctive immunohistochemical characteristics”. PEComa is now a widely accepted entity. Notwithstanding, some authors doubt of its existence as a distinctive tumour.1

PEComas are considered to be ubiquitous tumours and have been described in different organs, including mainly kidney, bladder, prostate, uterus, ovary, vulva, vagina, lung, pancreas and liver. Rarely have they been described in the bone, which is among other less common anatomical sites.1

Clinical caseInformed consent was obtained from the patient and no identifying data were obtained.

A male aged 24 years with a histological diagnosis of PEComa, presented with pain and a progressively increasing volume of the right proximal tibia of one year onset. The patient had no remarkable family or hereditary personal history of importance and laboratory tests were found to be without normal limits. No changes to calcium metabolism were identified.

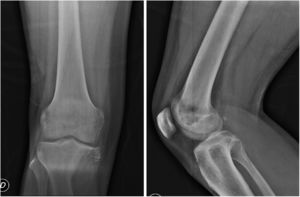

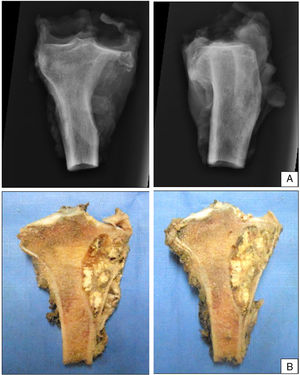

In plain X-rays (Fig. 1) a metaphysis epiphyseal lytic lesion was found of the right proximal tibia, with no periostic reaction and with extension to soft tissue in the anteromedial and posterior regions of the leg.

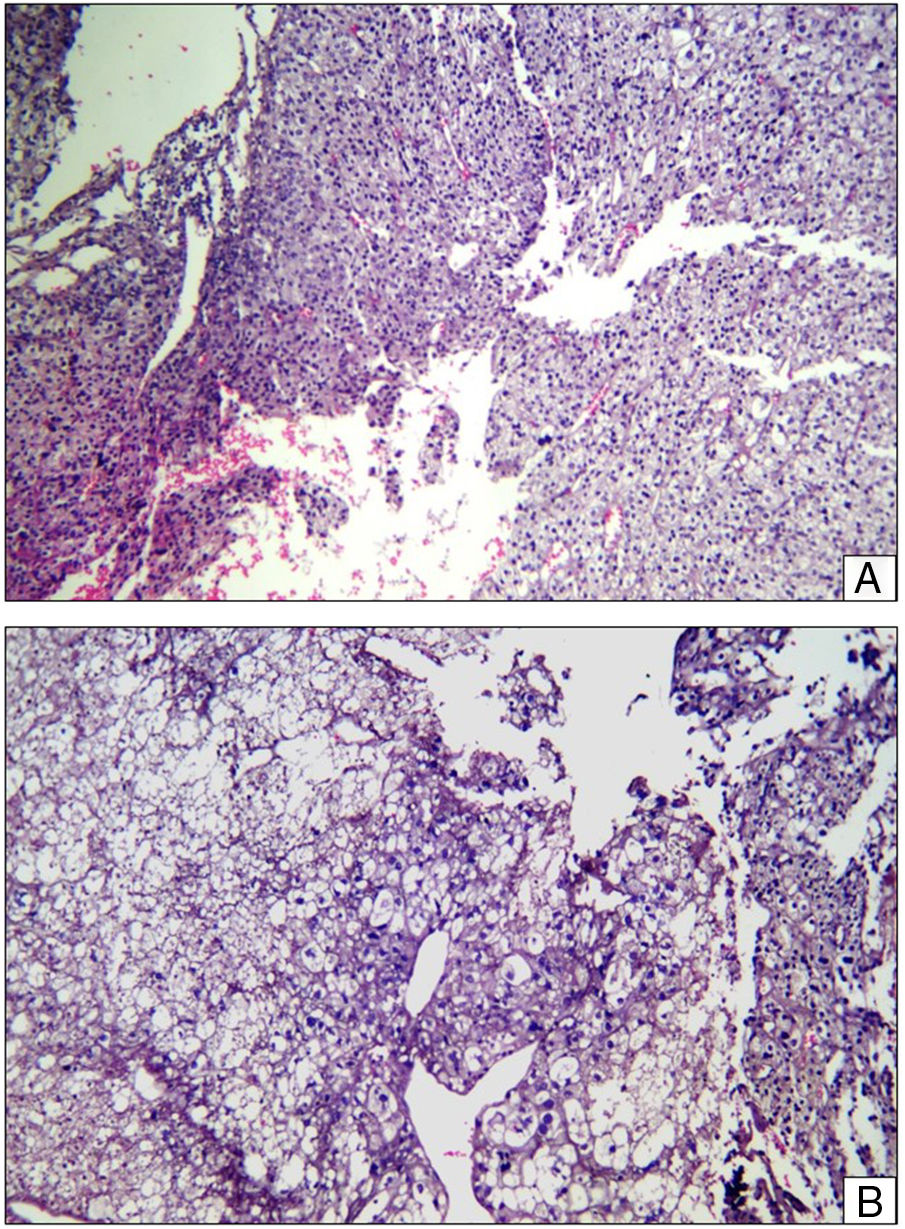

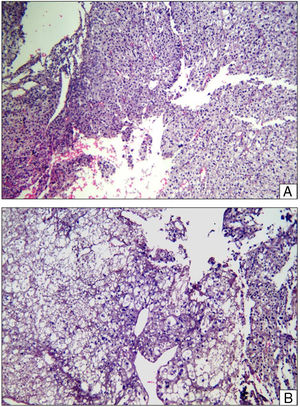

As part of the study protocol in the patient with a suspected osteo tumour incision, biopsy was performed, where the presence of a clear-cell malignant tumour was reported with cohesive epitheloid appearance around the vessels, clear granular cytoplasm and prominent nucleolus (PEComa morphology) (Fig. 2). The immunohistochemical report revealed: cytokeratin 8/18 (–), epithelial membrane antigen (–), HMB 45 (–), PAX-2 (–), renal carcinoma antigen (–), smooth muscle actin (–), microphthalmia transcription factor (–), S-100 (–), CD 99 (–), Melan A (–), PAX-8 (–), CD 117 (–).

Histopathological slice. (A) Layers of epitheloid cells with predominantly granular cytoplasm are observed, a central hyperchromatic nucleus and prominent nucleolus around the vascular spaces. Areas of haemorrhaging. Haematoxylin–Eosin ×20. (B) Layers of epitheloid cells of clear cytoplasm and in some cases vacuolated cells were observed with a central hyperchromatic nucleus, around vascular spaces. Haematoxylin–Eosin ×40.

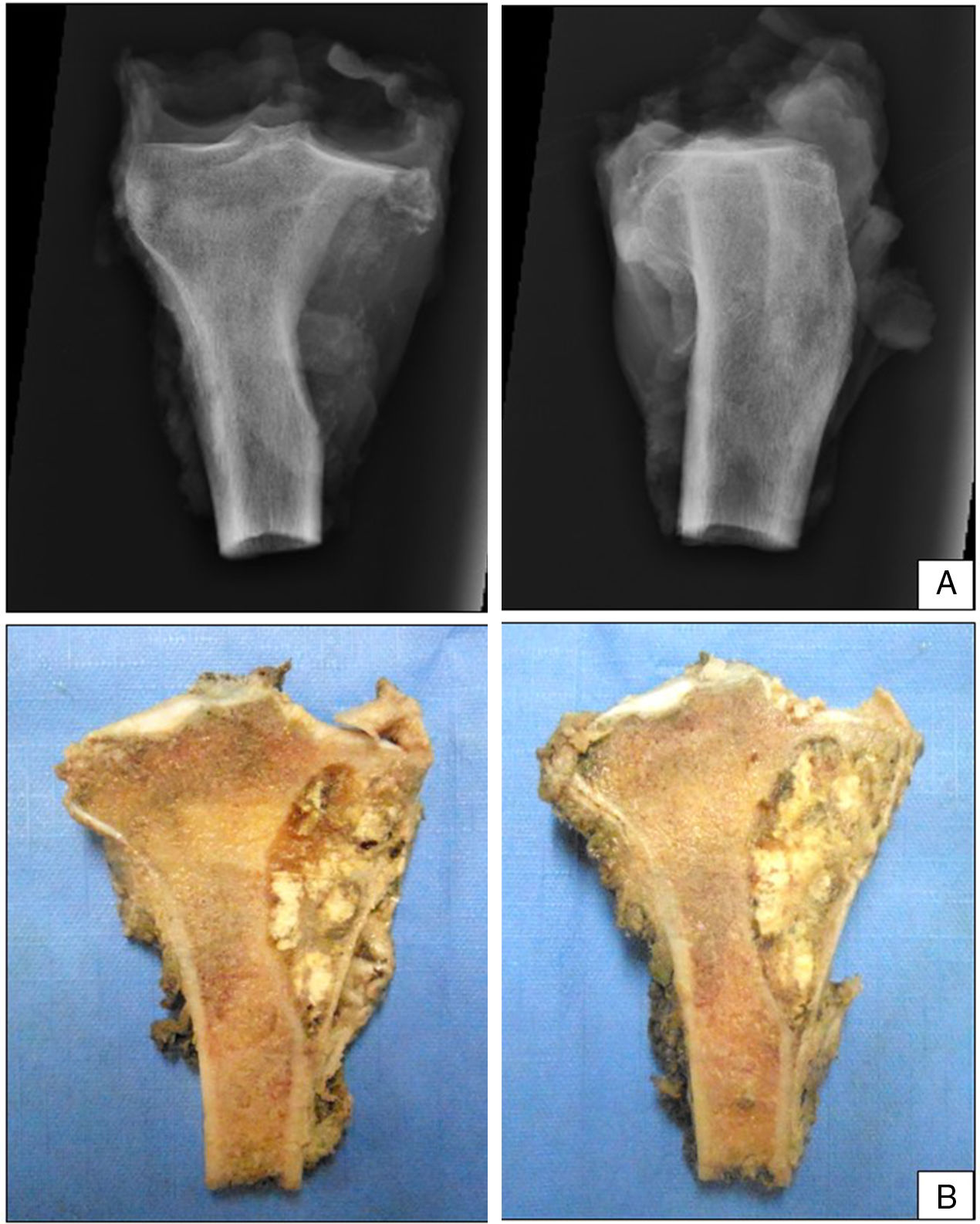

The patient continued with neo adjuvant chemotherapy treatment with epirrubicin/cisplatin for 3 cycles with an adequate response (tumour necrosis>90%), and an en bloc resection was therefore performed on the proximal tibia with wide surgical margins (Fig. 3) and skeletal reconstruction with prosthesis (GMRS Stryker proximal tibia, cemented, Mahwah, NJ) (Fig. 4). The pathological study of the surgical specimen reported tumour necrosis of 98% and post chemotherapy changes.

At the 24 month check up the patent was alive, with no further tumour disease and no added complications.

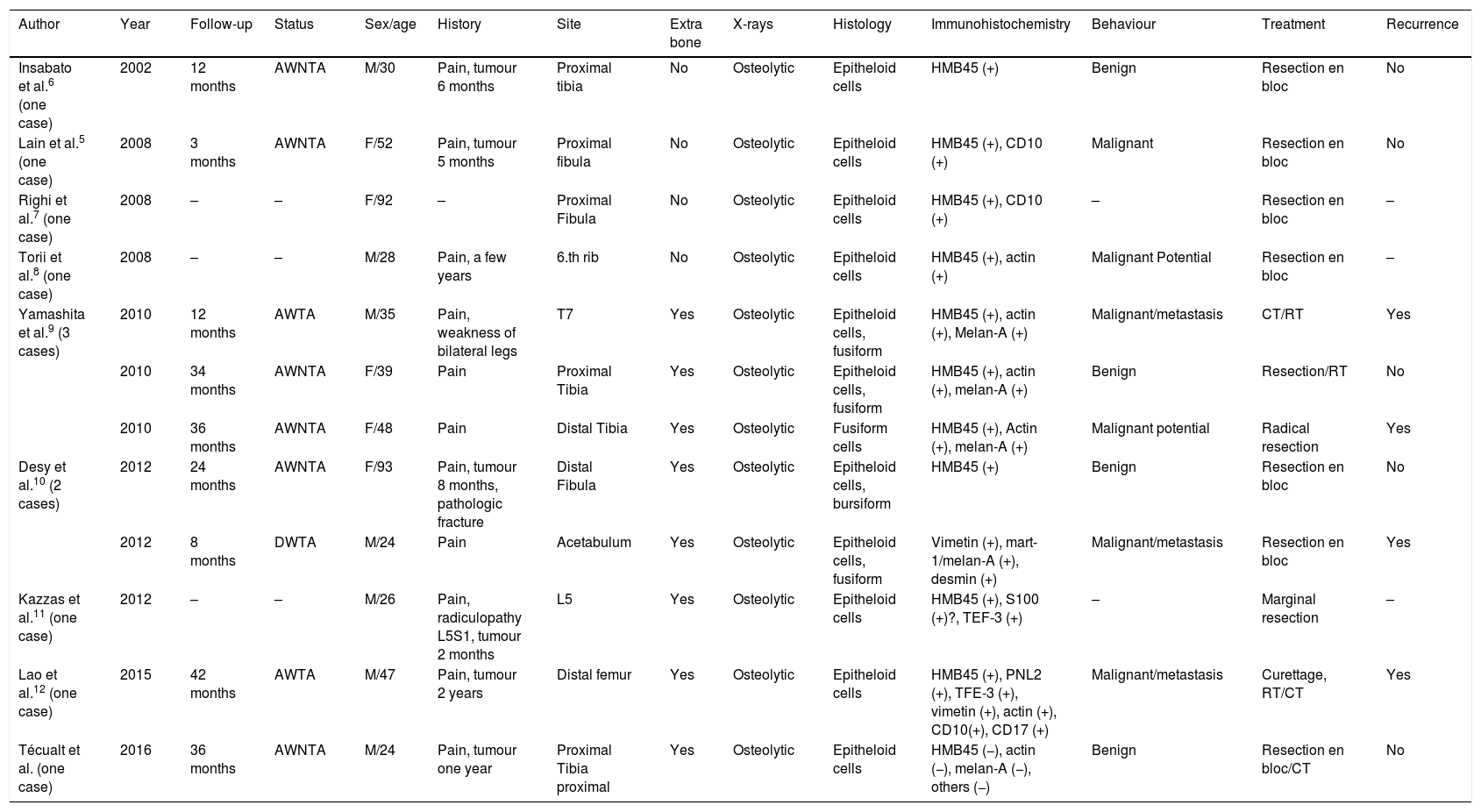

DiscussionPrimary bone PEComa is rare and few cases have been reported in the literature.5Table 1 enumerates the cases which have been reported up until now.5–12

Clinical characteristics of 12 primary bone PEComa.

| Author | Year | Follow-up | Status | Sex/age | History | Site | Extra bone | X-rays | Histology | Immunohistochemistry | Behaviour | Treatment | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insabato et al.6 (one case) | 2002 | 12 months | AWNTA | M/30 | Pain, tumour 6 months | Proximal tibia | No | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells | HMB45 (+) | Benign | Resection en bloc | No |

| Lain et al.5 (one case) | 2008 | 3 months | AWNTA | F/52 | Pain, tumour 5 months | Proximal fibula | No | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells | HMB45 (+), CD10 (+) | Malignant | Resection en bloc | No |

| Righi et al.7 (one case) | 2008 | – | – | F/92 | – | Proximal Fibula | No | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells | HMB45 (+), CD10 (+) | – | Resection en bloc | – |

| Torii et al.8 (one case) | 2008 | – | – | M/28 | Pain, a few years | 6.th rib | No | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells | HMB45 (+), actin (+) | Malignant Potential | Resection en bloc | – |

| Yamashita et al.9 (3 cases) | 2010 | 12 months | AWTA | M/35 | Pain, weakness of bilateral legs | T7 | Yes | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells, fusiform | HMB45 (+), actin (+), Melan-A (+) | Malignant/metastasis | CT/RT | Yes |

| 2010 | 34 months | AWNTA | F/39 | Pain | Proximal Tibia | Yes | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells, fusiform | HMB45 (+), actin (+), melan-A (+) | Benign | Resection/RT | No | |

| 2010 | 36 months | AWNTA | F/48 | Pain | Distal Tibia | Yes | Osteolytic | Fusiform cells | HMB45 (+), Actin (+), melan-A (+) | Malignant potential | Radical resection | Yes | |

| Desy et al.10 (2 cases) | 2012 | 24 months | AWNTA | F/93 | Pain, tumour 8 months, pathologic fracture | Distal Fibula | Yes | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells, bursiform | HMB45 (+) | Benign | Resection en bloc | No |

| 2012 | 8 months | DWTA | M/24 | Pain | Acetabulum | Yes | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells, fusiform | Vimetin (+), mart-1/melan-A (+), desmin (+) | Malignant/metastasis | Resection en bloc | Yes | |

| Kazzas et al.11 (one case) | 2012 | – | – | M/26 | Pain, radiculopathy L5S1, tumour 2 months | L5 | Yes | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells | HMB45 (+), S100 (+)?, TEF-3 (+) | – | Marginal resection | – |

| Lao et al.12 (one case) | 2015 | 42 months | AWTA | M/47 | Pain, tumour 2 years | Distal femur | Yes | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells | HMB45 (+), PNL2 (+), TFE-3 (+), vimetin (+), actin (+), CD10(+), CD17 (+) | Malignant/metastasis | Curettage, RT/CT | Yes |

| Técualt et al. (one case) | 2016 | 36 months | AWNTA | M/24 | Pain, tumour one year | Proximal Tibia proximal | Yes | Osteolytic | Epitheloid cells | HMB45 (−), actin (−), melan-A (−), others (−) | Benign | Resection en bloc/CT | No |

DWTA: dead with tumour activity; CT: chemotherapy; RT: radiotherapy; AWTA: alive with tumour activity; AWNTA: alive with no tumour activity.

We report case number 12 of primary bone PEComa since its first description made by Insabato et al. in 2002,6 and case number 3 in the proximal tibia. The long bones of the extremities tend to be involved in this presentation, and pain is the most common presentation characteristic, followed by pathological fracture and tumour,9 which were also found in our patient.

Our reported case is consistent with the affection site, the classical histopathological characteristics described for PEComa: clear cell epitheloids with clear granular cytoplasm, a prominent nucleolus and the locastin of these cells around the blood vessels. However, the immunohistochrmical report did not reveal any positive results for the marker normally found in this tumour cell line: MelanA, smooth muscle actin and HMB-45.

The histogenesis and normal/physiological counterpart of PECs are unknown, but several hypotheses have been proposed. One of these hypotheses is that the PEC derive from undifferentiated cells of the neural crest which express the dual phenotype of smooth and melanocytic muscle. A second hypothesis is that the PECs are of myoblast, smooth muscle origin with a molecular alteration which leads to the expression of melanogenesis and melanocytic markers. A third hypothesis is that the PECs have a pericytic origen.1 Furthermore, at least focally, the tumour cells of PEComa are closely arranged around the blood vessels, and on some occasions appear to compromise the muscle wall of blood vessels.9

Folpe et al. proposed the provisional classification of PEComa into “benign” “uncertain malignant potential” and “malignant”. A significant association was found between the size of the tumour over 5cm, infiltrating growth pattern, high nuclear grade, high cellularity, necrosis and mitotic activity above 1/50 by high power field. It has been suggested that the PEComas, with 2 or more characteristics of concern, may be classified as “malignant” with recognition that the clinically aggressive disease may not be histologically observed in all malignant neoplasms. In our case the criteria described by Folpe et al. were met. It has also been suggested that these characteristics may be classified as having an “uncertain malignant potential”.13

Malignant PEComa may be a highly aggressive disease, leading to many forms of metastasis and death, as would be expected of high grade sarcomas and reports exist that malignant PEComas have metastasized after 7–9 years in primary sites which are not always bone.1

At present it appears that the only approach in the treatment of PEComas in aggressive cases is surgery, since radio and chemotherapy have not demonstrated significant outcomes. However, this information derives from anecdotal cases and therapeutic trials have not been implemented. One of the clear difficulties in carrying out this type of study is the rarity of the disease.1

In our case we used neo-adjuvant chemotherapy due to low local experience available in the treatment of this type of tumour, the first case to be found in this country. However, because the pathology reported changes suggestive of a probable sarcoma and atypia, we decided to initiate treatment with this mode of therapy. Once the histopathological study had been reviewed by the pathologist expert in bone tissue, no similarity was found with any other type of sarcoma and it was not until subsequent reporting of the surgical specimen of resection that definitive diagnosis of PEComa was made, following additional information from its immunohistochemical study.

The prognosis of PEComa is variable and mainly depends on histopathological characteristics.10

ConclusionsThis is the first case of bone PEComa reported in Latin America. Its clinical and pathological characteristics were demonstrated but no immunohistochemical markers were found and this final point does not coincide with what has been described as standard. We believe this may be due to ethnic variations which have not yet been described.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence V.

Please cite this article as: Técualt-Gómez R, Atencio-Chan A, Amaya-Zepeda RA, Cario-Méndez AG, González-Valladares R, Rodríguez-Franco JH. Neoplasia de células epiteloides perivasculares (PEComa) tibial. Reporte de un caso y revisión de la literatura. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;93:239–245.