The vascular anatomy of the talus attracts intense research being not always easy to understand.

The high intraosseous variability together with the anatomical characteristics makes some areas of the talus more prone to vascular compromise.

The aim of this study is to describe the vascularisation of the talus, both intraosseous and extraosseous.

Material and methodsFrom the literature reviewed, we have developed a graphic scheme that allows easy observation of the irrigation distribution. To this end, nineteen anatomical dissections of human cadaveric feet have been carried out. Fifteen fresh-frozen slices have been cut in different planes and prepared using the modified Spalteholz technique and latex injection with blue and black ink to visualise the vascular network. In addition, the study has been complemented with a comprehensive literature review on this subject.

ResultsThe findings allowed us to conclude that the posterior tibial artery provides the most important blood supply to the neck and body of the talus through the tarsal canal artery and the deltoid branch.

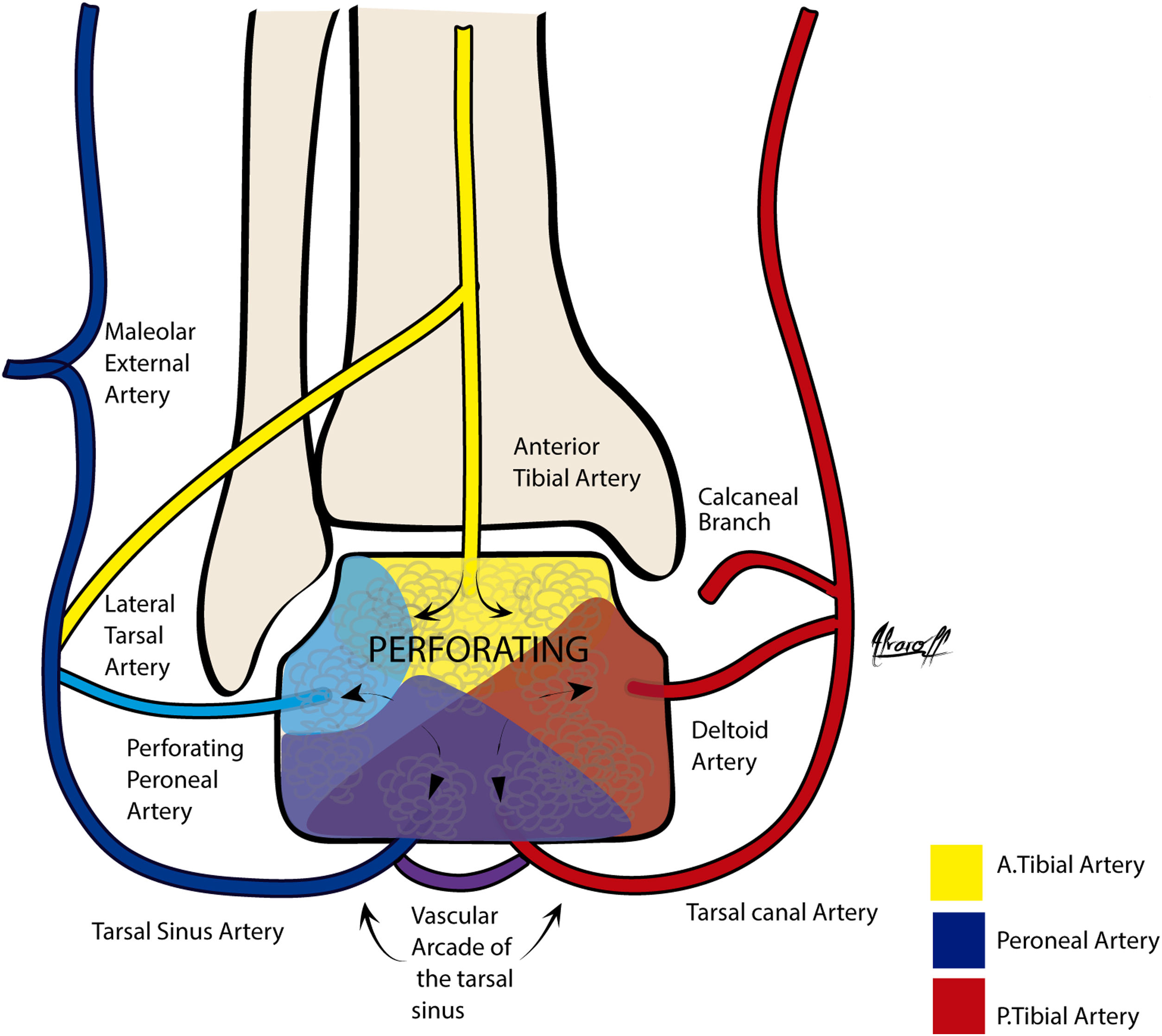

The anterior tibial artery splits in the dorsal pedis artery, for the head and neck, and the lateral tarsal artery which throughout anastomoses breeds the tarsal sinus artery.

The perforating peroneal artery branches out from the peroneal artery, creating an intraosseous anastomosis for the body and the posterior process.

ConclusionThe results obtained have contributed to develop a graphical representation that we present in this study, which allows a simple understanding of the intraosseus and extraosseus vascularisation of the talus.

La anatomía vascular del astrágalo ha sido motivo de investigación por parte de muchos autores, la complejidad de su análisis ha llevado a que no siempre sea fácil de comprender.

Sus características anatómicas hacen que algunas áreas sean más susceptibles de sufrir daños y compromisos vasculares tras lesiones traumáticas.

El objetivo de este estudio es describir la vascularización del astrágalo, tanto a nivel intraóseo como extraóseo, para obtener una representación gráfica que permita fácilmente conocer su red de irrigación vascular.

Material y métodosSe han realizado las disecciones y análisis de diecinueve piezas anatómicas de cadáver humano. Quince de esas piezas se han seccionado en diferentes planos y se han preparado utilizando la técnica de Spalteholz modificada con inyección de látex con tinta azul y negra para visualizar la red vascular. Además, el estudio se ha complementado con una revisión bibliográfica exhaustiva sobre el tema.

ResultadosLos hallazgos han permitido concluir que la arteria tibial posterior aporta la irrigación más importante al cuello y cuerpo del astrágalo a través de la arteria del canal tarsiano y la rama deltoidea.

La arteria tibial anterior se divide en la arteria dorsal del pie para la cabeza y el cuello, y la arteria tarsal lateral que a través de las anastomosis origina la arteria del seno del tarso. La arteria peronea perforante, procedente de la arteria peronea, crea una anastomosis intraósea para el cuerpo y el proceso posterior.

ConclusiónLos resultados obtenidos han permitido elaborar una representación ilustrada de las áreas de irrigación propias y comunes, que permite comprender de forma gráfica y sencilla la vascularización intraósea y extraósea del astrágalo.

The talus is the second largest bone of the tarsus.1 Its function in the ankle and foot, acting as an intermediary link, allows for the coupling of the rotational movements of the tibia and fibula with the foot. In this way it participates in the distribution of body weight, facilitating the adjustment of the feet on the ground, and generally determines a large part of the behaviour of the so-called periastragaline complex.1,2

This bone is characterised by several idiosyncrasies which make if more vulnerable to osteonecrosis, particularly when its blood supply alters.1,3 Approximately 60% of its surface area is covered by articular cartilage, where vessels cannot penetrate. It has no muscle or tendon insertion and there are not enough perforating vessels or collateral irrigation to ensure intraosseous vascular supply.1,2

Both extraosseous and intraosseous vascular irrigation of the talus has been previously described in other articles using different descriptive techniques.4–8

The aim of this study is to describe the intraosseous and extraosseous vascular irrigation of the talus using a graphic representation, based on findings obtained from preparations made, and the literature consulted. The purpose of the graphic representation we present is to illustrate the vascular supply of this bone in an easily recognisable manner.

Material and methodsFifteen frozen pieces of human cadaveric feet were used for this study from the Donation Service of the Department of Anatomy of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Barcelona. The age range was 70–90 years. The samples were cut in the 3 anatomical planes in .5cm preparations. The modified Spalteholz technique was used to study the intraosseous vascular supply. The specimens were dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol from 49% to 99%. The ethanol was changed once a week for 2 months. After dehydration, the samples were immersed in ethanol until it was replaced by a toluene solution, twice, in the space of one week. Finally, in order to visualise the intraosseous vascular supply of the talus, the specimens were immersed in methyl salicylate. Six of the 15 specimens were selected to be photographed, those with the best definition of the vascular tree, in order to be clearly illustrative and descriptive. The remaining pieces, although they shared the characteristics of the vascular provision described in our findings, were not photographed for this study as they presented some anatomical destructuring that did not allow an optimal characterisation and graphic comprehension for the reader.

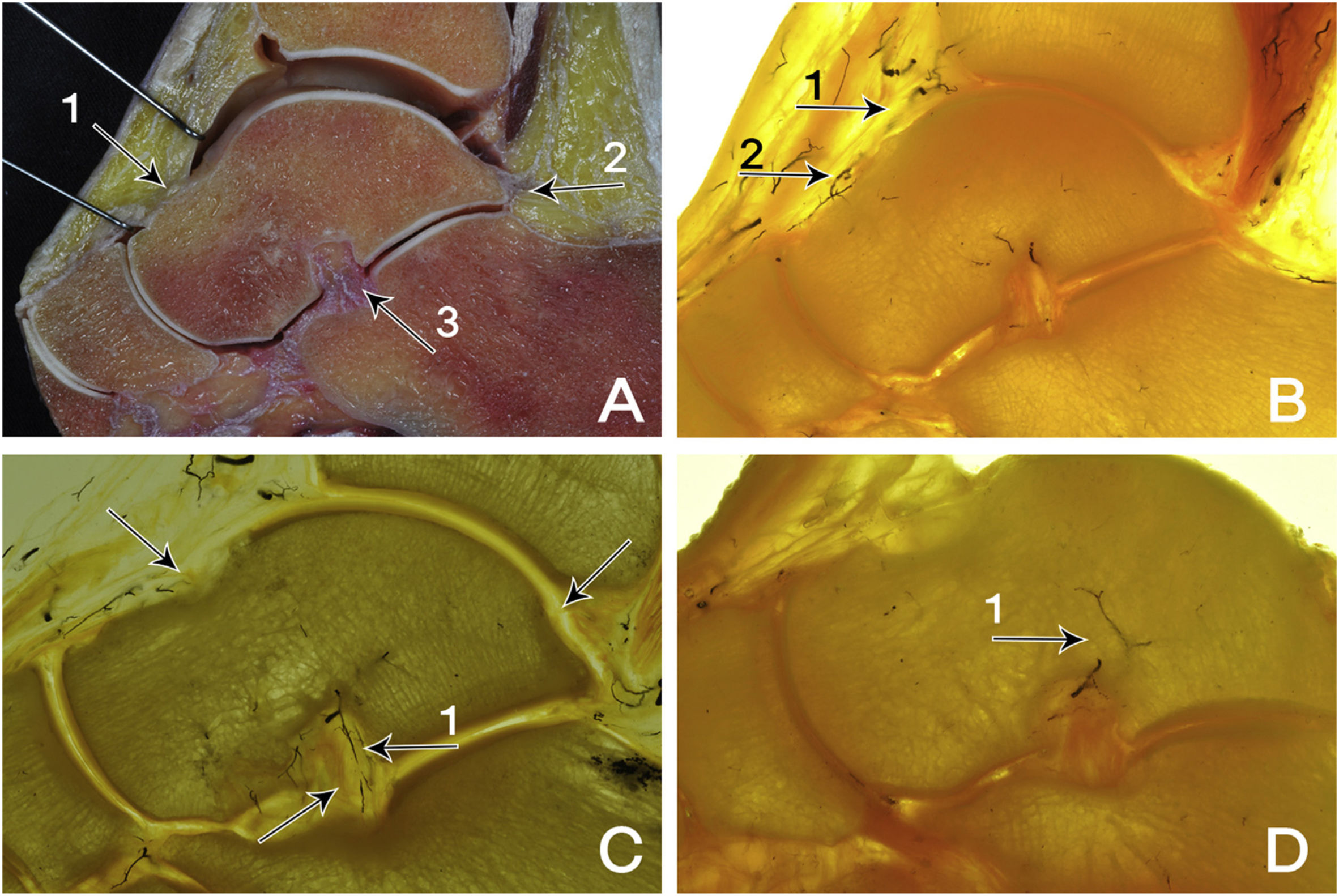

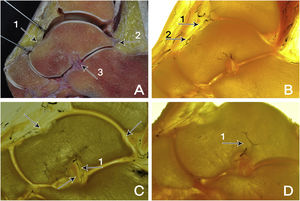

ResultsAnalysis of the extraosseous and intraosseous vascular supply of the specimens prepared with the modified Spalteholz technique showed that this supply comes from the posterior tibial artery, the anterior tibial artery and the peroneal artery. It was possible to demonstrate and visualise in the sagittal sections the 3 anatomical points of vascular entry, which are: the insertions of the talocalcaneal interosseous ligament; the posterior talofibular ligament and, anteriorly, the articular capsular insertion at the neck of the talus (Figs. 1 and 2).

(A) Sagittal section. The large extension of the cartilaginous articular surface of the talus is seen in fresh section and the capsular insertion is shown (1), through which the vessels penetrate at the level of the neck. Posteriorly, the posterior talofibular ligament is shown (2). Below, the insertions of the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament (3). (B) Sagittal section. Anterior tibial artery (1). Branch of the dorsal pedal artery (2). (C) Sagittal section. Prepared section showing the entry of the main arteries supplying the talus: tarsal sinus artery (1). (D) Sagittal section. The tarsal sinus artery (1) provides much of the intraosseous vascular supply, especially in the medial and plantar portion of the neck.

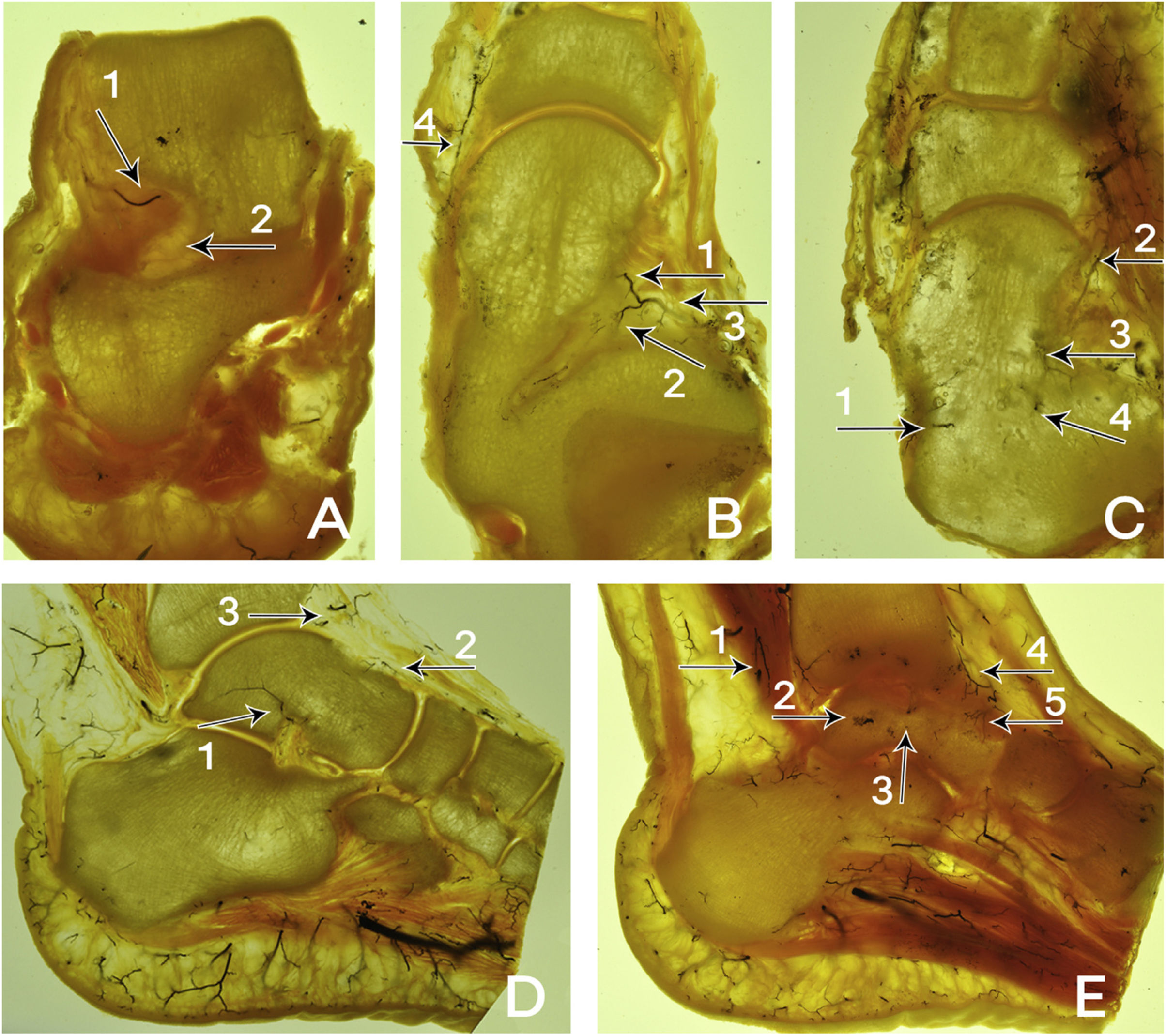

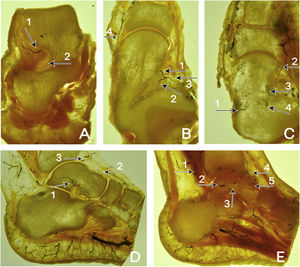

(A) Coronal section. Tarsal sinus artery (1) and talocalcaneal interosseous ligament (2). (B) Cross section. Dorsal pedal artery (1), lateral tarsal artery (2), branches of the anterior tibial artery (3). (C) Cross section. Posterior tibial artery (1). On the other side, the anterior tibial artery (2) dividing into the dorsal pedal artery (3) and the lateral tarsal artery (4). (D) Sagittal section. Tarsal sinus artery (1). Above the neck of the talus, the dorsal pedal artery (2) is seen coming from the anterior tibial artery (3). (E) Sagittal section. On the left side, the peroneal artery (1) and the perforating branch of the peroneal artery (2) with the formation of the intraosseous anastomoses (3) can be seen. At the upper end of the neck, the anterior tibial artery (4) and the dorsal branch of the dorsal pedal artery (5).

We observed that the talar neck has little articular cartilage due to its ligamentous insertions, and it is in this space that the vessels penetrate. This is particularly evident in fresh specimens prepared with blue and black latex ink (Figs. 1 and 2). Thus, the most irrigated areas of the talus are located in the superior and inferior surface of the talar neck, in the sinus of the tarsus, the tarsian canal and in the posterior tubicle of the talus (Fig. 1A–C).

The posterior tibial artery supplies the deltoid branch for the superficial medial section of the body, as well as some branches for the calcaneus (Fig. 1C). The other branch, the tarsal canal artery, supplies the lower section of the talus through the tarsal sinus vascular arcade (Fig. 1C and D).

The anterior tibial artery originates through the dorsal artery of the foot to supply the dorsolateral part of the head and neck, and continues its course to supply the medial part of the foot (Fig. 1B and C).

The other branch of the anterior tibial artery is the lateral tarsal artery, which anastomoses with the artery of the tarsal sinus to provide vascularisation of the head and body (Fig. 2C).

The tarsal sinus artery supplies the talar neck through anastomosis, particularly for the medial plantar section of the neck (Fig. 2A–D).

The peroneal artery with its branch, the perforating peroneal artery, forms an intraosseous anastomosis for the lateral part of the talar body and in particularly for the posterior process.

All of these preparations show that there is an extraosseous and intraosseous vascular network guaranteeing supply throughout the talus. High anatomical variability exists, which conditions those areas more open to avascular necrosis after trauma.

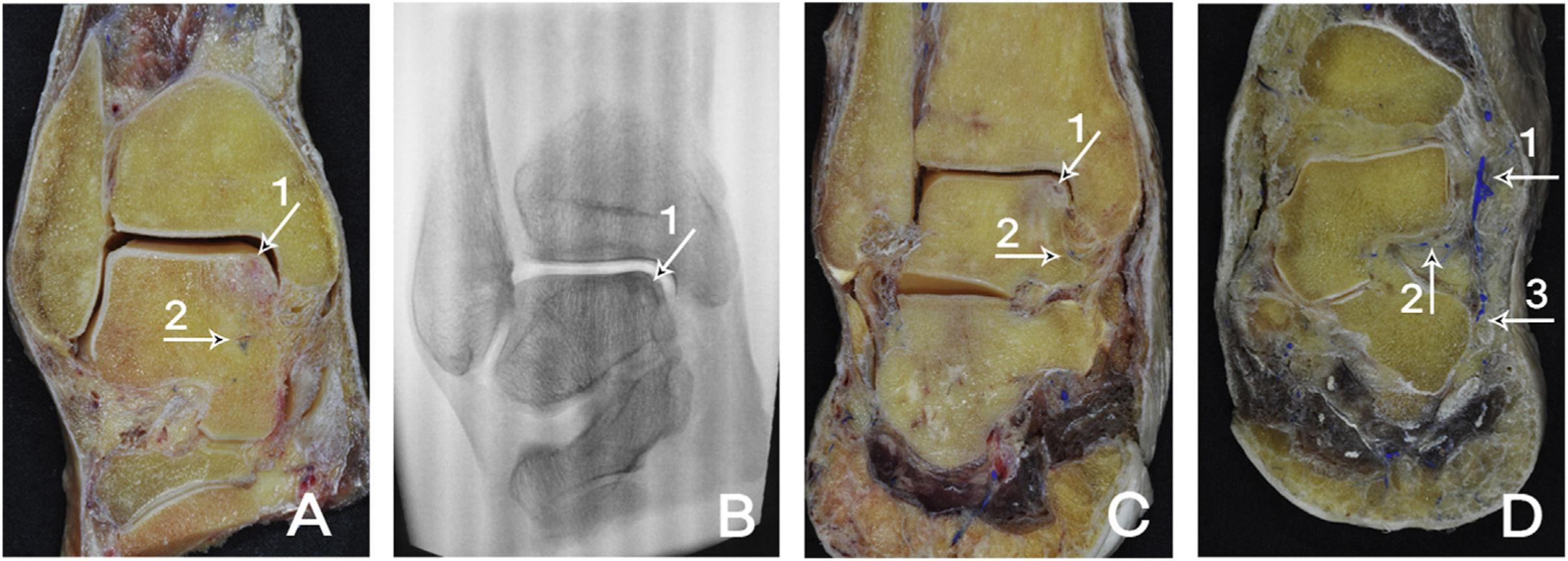

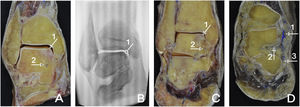

In the dissection of one of the specimens signs compatible with an osteonecrotic injury were found by chance (Fig. 3A and B).

(A) Coronal section. Signs compatible with osteonecrosis of the superomedial segment of the talus body (1). Deltoid artery (2). (B) Coronal section. Radiological image. Radiological sign compatible with osteonecrotic lesion of the talus (1). (C) Coronal section. Osteochondral lesion (1). Marked with blue latex ink, the deltoid branch can be seen (2). (D) Coronal section. Posterior tibial artery (1). Marked with blue latex ink, the deltoid branch is observed (2). Calcaneal branch of the posterior tibial artery (3).

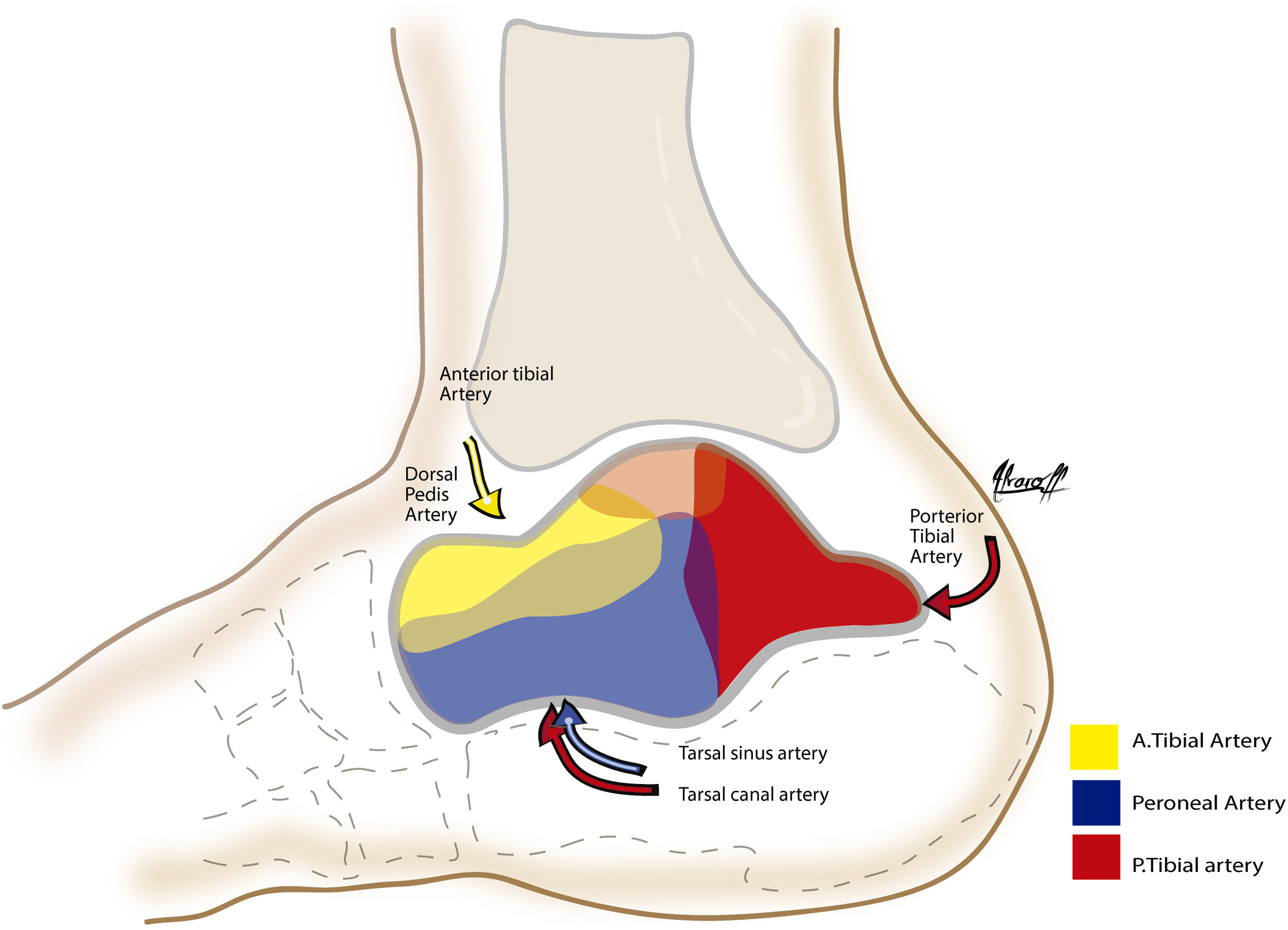

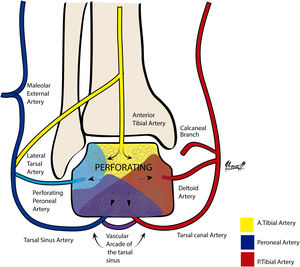

Based on the findings obtained from the dissection and preparation of the specimens of this study, we have been able to produce a pictorial representation that illustrates in a contrasted, clear and schematic manner the intraosseous and extraosseous irrigation network of the talus (Figs. 4 and 5).

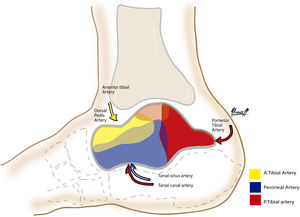

Sagittal view. The graphic representation of the vascular supply of the talus is shown in 3 colours. Yellow: the anterior tibial artery encompassing most of the head and neck in the dorsal segment via the dorsal pedal artery and a smaller portion via the perforating branch of the peroneal artery to the body. Blue: the contribution of the peroneal artery is shown, but the major contribution of the peroneal artery will be through the perforating peroneal branch together with the lateral tarsal branch of the anterior tibial artery to form the large tarsal sinus network, which constitutes the most important intraosseous network of the talus represented with a purple intermediate colour. Red: the posterior tibial artery is the second most important, comprising the entire intraosseous network that irrigates the posterior third of the talus through the deltoid and calcaneal branch, and also contributes to form the tarsal sinus plexus, represented in purple.

Coronal view. Graphic representation of the talus blood supply in 3 colours.

Yellow: the anterior tibial artery penetrates through the cartilage-deprived area at the neck of the talus with the dorsal pedal branch of the anterior tibial artery.

Blue: the major proportion of the intraosseous supply to the talus comes through the tarsal sinus vascular arcade marked in purple.

Red: Posterior tibial artery represented in the deltoid, calcaneal and tarsal canal branches.

Talus fractures represent 2% of lower limb fractures.9

Of all foot and ankle fractures, talar neck fractures account for under 1%,10 but they are the most affected part of the talus (up to 50% of cases).2

It is difficult to understand the mechanism of the talus vascular supply due to the peculiarities of its anastomotic network and due to complicated comprehension with graphic and anatomical representations on the subject.

It has already been reported and this study reinforces that the talus receives its blood supply from the branches of 3 main arteries of the foot: the peroneal artery, the anterior tibial artery and the posterior tibial artery.5

The main blood supply is directed at the head of the talus and comes from the tarsal canal artery and the deltoid artery, branches of the posterior tibial artery6 and the tarsal sinus artery.4

This study reproduces that described by other authors, regarding the vascular supply of the talar neck through anastomotic branches of the tarsal sinus artery.6

The main arteries of the talar body arise from the neck, and for this reason, displaced neck fractures can interrupt the blood supply to the body.

Neck fractures compromise the blood supply to the central and lateral two-thirds of the talar body, and osteonecrosis may develop in this area.1,5

The close relationship between the displacement of the talar neck fracture and the risk of damaging the blood supply to the body is due to the fact that its blood supply is retrograde from the head to the body, so that, if it is interrupted, there is no other vascular source to irrigate the body.3,9,11

Given the particular vascular and anatomical characteristics of the talus, it has been the subject of previous studies by various authors.4–8

The plastination method used in this study, the modified Spalteholz technique, has proven to be very useful for visualising the intraosseous vascular network.

Our findings are similar to those of other studies, revealing that the talus receives a highly vulnerable blood supply.1,5,7,8

The specimens used in our study have led to the findings of the main branches and anastomoses of the three main arteries of the talus.

The limitations of this study include the quality of the examples associated with the age of the specimens, and the sample size, limiting generalisation to the population as a whole. Furthermore, the description of the vascular source is a qualitative method and no accurate method of verification of the irrigated surface of the talus was available. Lastly, plastination technique limitations may have obscured assessment of the intraosseous irrigation.

ConclusionWe may determine that in the talus there is a particular intraosseous blood distribution, due to its anatomical features.

This study corroborated that the talus has a vulnerable blood supply, since most of its surface area is covered by articular cartilage and this limits the penetration of the vessels towards the bone interior. As a result, several areas of the bone are more easily compromised when blood supply is altered.

Vascularisation of the talus is complicated and not easy to understand. The graphic representation in this study aids comprehension.

We believe it to be of great use when studying this area to have a graphic and schematic representation to quickly and easily understand the talus blood supply and that this will provide an aid in the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of fractures or lesions of this bone.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.