According to INTERPOL, dental comparison is one of the most reliable primary means of identification. However, it requires adequate antemortem (AM) records to be compared with postmortem (PM) information. Orthodontics and dentomaxillofacial orthopae (OOD) is a dental speciality that uses procedures and devices with periodic controls and quality imaging for its purposes. A scoping review is presented (“forensic”AND“identification”AND“orthodontics”) in the scientific literature, of cases in which orthodontic records have been successfully used for forensic identification. Of 11,413 articles, 9 reports were included that responded to the search objective. Imaging records were the ones with the highest quality and availability. The AM orthodontic data is of high quality, but the scarcity of reports shows a tendency to be underestimated in the literature. Because OOD records are reliable, imaging backup should be promoted in all dental activities. It is recommended to report these cases as learning opportunities in the medical-legal field.

Según la Organización International de Policía Criminal (INTERPOL), el cotejo odontológico es uno de los medios primarios más fiables para la identificación. Sin embargo, necesita de registros adecuados antemortem (AM) para su cotejo con la información postmortem (PM). La ortodoncia y ortopedia dentomaxilofacial (OOD) es una especialidad odontológica que se utiliza para sus fines, procedimientos y dispositivos de controles periódicos, radiografías y fotografías de calidad. Se presenta una revisión con búsqueda sistemática («forensic» AND «identification» AND «orthodontics») en la literatura científica de artículos que reporten casos en los que registros ortodóncicos hayan sido exitosos para la identificación forense. De 11.413 documentos fueron incluidos 9 reportes que respondieron al objetivo de búsqueda. Los registros radiográficos y fotográficos fueron los de mayor calidad y disponibilidad. La información ortodóncica AM es de alta calidad, pero la escasez de reportes muestra una tendencia a que esa información sea infraestimada en la literatura. Debido a que los registros OOD son confiables, debe promoverse el respaldo radiográfico y fotográfico en toda actividad odontológica. Se recomienda reportar estos casos como oportunidades de aprendizaje en el ámbito médico legal.

Forensic odontology consists of the use of odontological science within the legal field. It includes different areas of working, among which the identification of unknown human remains using dental characteristics is now well-established among forensic scientific disciplines.1 However, although teeth have individualised features which enable identification, the methodology is essentially based on comparison, so that suitable and exact records are needed from the lifetime of the individual in question (antemortem (AM) data) so that they can be compared with the information obtained from the cadaver (postmortem (PM) data).2

Dentomaxillofacial orthodontology and orthopaediatrics (DOO) is the odontological speciality which covers the care, supervision and guidance of the development of the masticatory system and the correction of dentofacial structures, including conditions which require dental movement for treatment, as well as establishing aesthetic harmony in the maxillary and mandibular structures of the face. Due to the complexity of their cases and the considerable amount of time they spend working with their patients, DOO specialists routinely prepare different records for the corresponding clinical registry. These records are fundamental for planning and undertaking the therapies involved. Information in writing as well as radiographic and photographic data, plaster models and other specific documents make up a clinical file which allows orthodontists to not only make initial diagnoses, but also to prepare prognoses and control the progress of treatments.3

We present a review which involved a systematic search for cases in which orthodontic registries and AM data made it possible to identify human remains in forensic contexts.

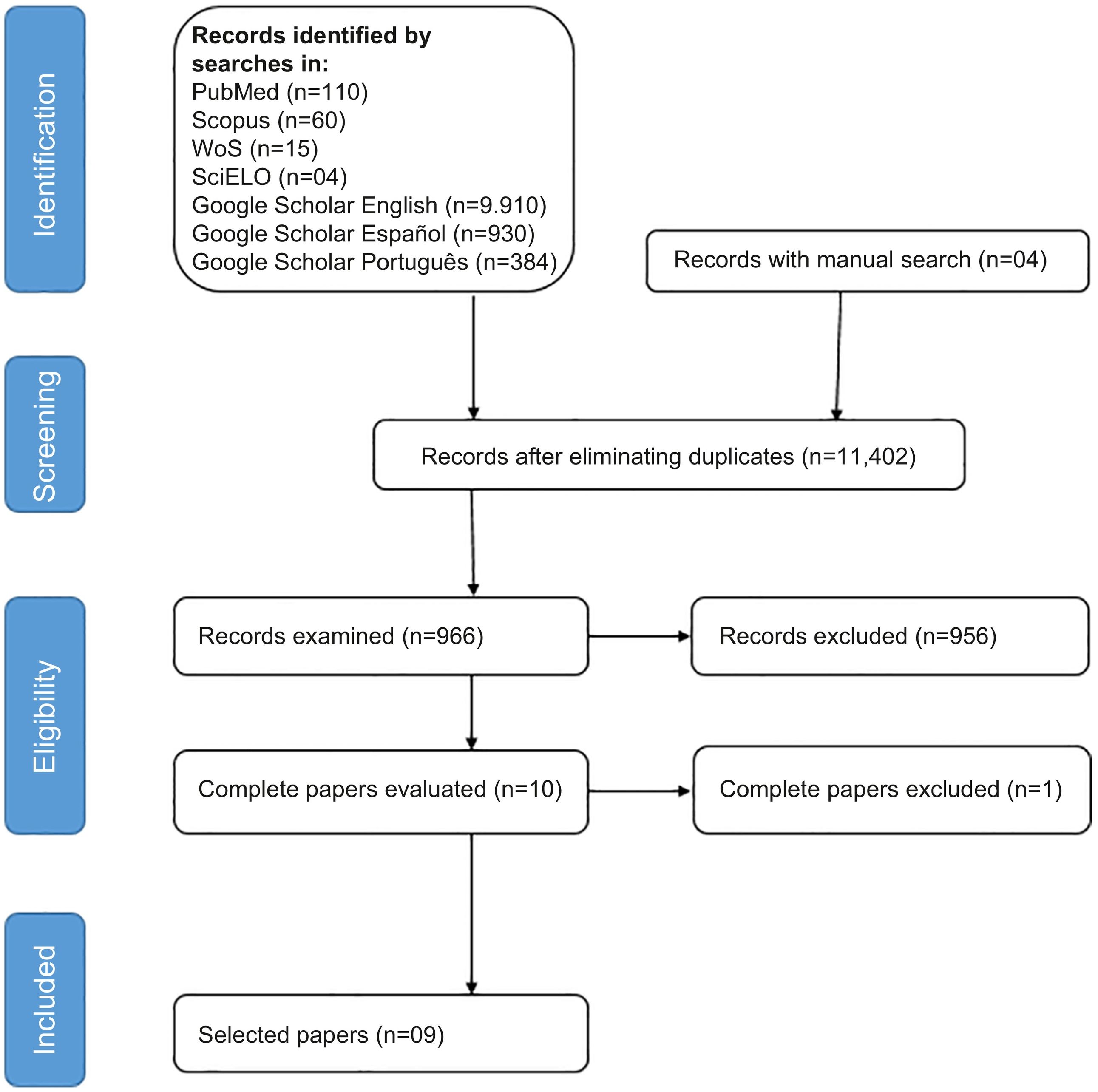

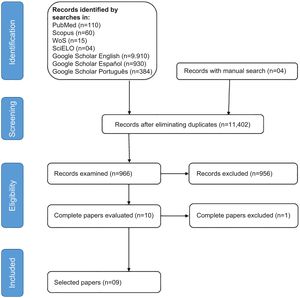

Material and methodsA systematic search of the literature was conducted using PRISMA methodology and protocols.4 Reviews of this type have been described as the appropriate methodology if the aim is to answer broad research questions, identify gaps in knowledge, discover the nature of available evidence and postulate new specific research questions.5 The specific strategy used for this purpose was to search for the terms “forensic”, “identification” and “orthodontics”, in English, Spanish and Portuguese in the PubMed, Scopus, WoS, SciELO and Google Scholar databases. Taking the references to the documents that were identified as basis, an additional manual search was conducted. Complete papers which described cases of the forensic identification of human remains based on orthodontic records were included without any time limit. Books, theses, patents, letters to the editor, presentations in congresses and documents which did not fit the research objective were excluded. Document screening and eligibility were systematised as follows: a) document type, b) title, c) abstract and d) complete reading. Papers were independently identified by 2 calibrated observers, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

ResultsPapers were identified on 16 April 2021, making it possible gather 11,413 documents. Screening, eligibility and selection criteria were applied from 16 April to 11 May 2021, resulting in a total of nine x 2 papers reporting 9 cases that fulfilled the search objective (Fig. 1).

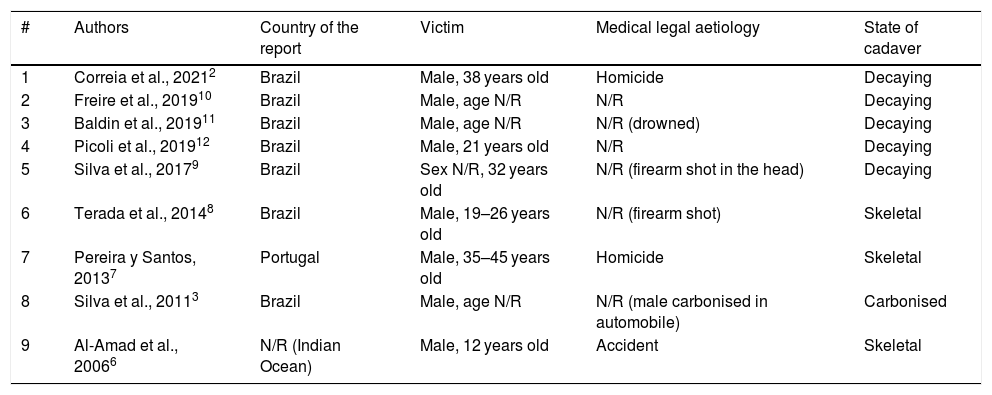

The papers were published from 2006 to 2021 by a total of 39 authors. Seven (77.7%) of the nine case reports which fulfilled the search objective occurred in Brazil, while one occurred in Portugal and the other was in an unspecified geographical context of the Indian Ocean. 32 (82%) of the total number of 39 authors were Brazilian, and Ferreira da Silva (Goiás, Brazil) stands out with 4 papers, while Franco (Curitiba, Brazil) and Paranhos (Bauru, Brazil) were each the author of 2 papers. The institution with the highest level of participation was the Goiás Federal University, Brazil, with four associated publications (44.4%). Respecting the victims, in eight of the nine cases (88.8%), the individuals were men (and one report did not mention the sex of the victim); five (55.5%) of the cadavers were in a state of putrefaction, while in three cases (33.33%), they were in a state of skeletal reduction and in one case (11.11%), the victim was found carbonised within an automobile. Their ages ranged from 12 to 45 years old, although in three cases, the reports did not mention this datum (Table 1). Only three cases reported the medical legal cause of death: one death was accidental during the 2004 Indian Ocean tidal wave,6 and there were two cases of homicide.2,7 Although the other papers did not contain this information, two of them reported death caused by firearm,8,9 although without clarifying whether the shots were due to suicide or homicide.

Cases identified in this review.

| # | Authors | Country of the report | Victim | Medical legal aetiology | State of cadaver |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Correia et al., 20212 | Brazil | Male, 38 years old | Homicide | Decaying |

| 2 | Freire et al., 201910 | Brazil | Male, age N/R | N/R | Decaying |

| 3 | Baldin et al., 201911 | Brazil | Male, age N/R | N/R (drowned) | Decaying |

| 4 | Picoli et al., 201912 | Brazil | Male, 21 years old | N/R | Decaying |

| 5 | Silva et al., 20179 | Brazil | Sex N/R, 32 years old | N/R (firearm shot in the head) | Decaying |

| 6 | Terada et al., 20148 | Brazil | Male, 19–26 years old | N/R (firearm shot) | Skeletal |

| 7 | Pereira y Santos, 20137 | Portugal | Male, 35–45 years old | Homicide | Skeletal |

| 8 | Silva et al., 20113 | Brazil | Male, age N/R | N/R (male carbonised in automobile) | Carbonised |

| 9 | Al-Amad et al., 20066 | N/R (Indian Ocean) | Male, 12 years old | Accident | Skeletal |

N/R: not reported.

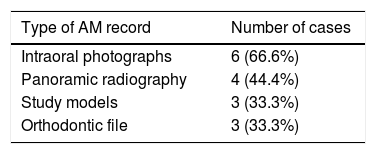

The most frequent orthodontic evidence found in the cadavers (PM information) consisted of brackets and arches, in six of the nine cases (66.67%), while in two cases, it was the retainer system (22.22%) and in one case, the presence of brackets only (11.11%). In all cases, good quality AM information was available which could be compared to the PM information, making it possible to positively identify the victims. Table 2 shows the type of AM orthodontic record used in the identification process.

DiscussionGiven the high quality of the AM orthodontic information reported in the cases that were detected, it is curious that few papers were identified in this review. Silva et al. state that although intraoral photographs are included in the AM information sources that can be used forensically, DOO is probably one of the few specialities which often use them in their routine practice,9 which would explain the small number of reported cases. Even though there are sufficient references which underline the value of orthodontic data for forensic identification,13–15 the fact that only nine cases are included in this review agrees with a tendency described by Madea, who states that case reports are considered to stand at a low level in the evidence-based medicine hierarchy because it is anecdotal, so that some journals refuse to publish them.16 Nevertheless, we agree with this author that case reports within a forensic context may help to identify specific patterns, new criteria for evidence or to increase knowledge of particular experiences, which in the subject reviewed is a point that has to be covered.16 Although restricting inclusion to case reports in this scoping review may be considered to be a limitation of the study (given their low status as scientific evidence), we believe that this makes it possible to appreciate actual experience in the use of DOO data as AM information. This fulfils not only the opportunities mentioned by Madea for case reports,16 as it also achieves what Armstrong et al. suggest5 for reviews of this type, as it permits the formulation of new hypotheses and potential research projects in this area.

There is agreement that in all odontological activity it is necessary to keep properly prepared clinical records that are updated and in organised registries, including complementary studies and communications between odontologists and their patients; nevertheless, this argument is even stronger for orthodontologists: Abdelkarim and Jerrold believe that a high quality orthodontic clinical file is a sign of good quality care. Excellent documentation says much about the skill and organisation of the orthodontologist, which in turn increases their credibility. Less expert doctors would be less likely to document treatment, but orthodontologists are expected to keep permanent records of the acts and activities which occur during patient–professional contacts.17 Within the forensic context, and more specifically that of comparative identification, the complexity of DOO treatments leads to documentation that typically contains a large number of complementary examinations—which are of course of high legal value in the practice of orthodontology— and these may be obtained without significant distortion as high quality sources for forensic use as AM information.8 Such availability is unfortunately exceptional in identification procedures, where difficulties have been reported in accessing suitable records,18 which places DOO in a privileged position as the producer of valuable AM information. In the case reported by Correia et al., the large number of documents used in the positive identification of the victim (records of visits, repair work, endodontic procedures, prosthesis, plaster models, frontal and lateral intraoral photographs, panoramic X-rays and left and right bitewing radiographies) had an orthodontological origin, as they were generated 6 years previously and supplied by the presumed victim’s family.2 Picoli et al. describe a case of positive identification based on analysis of the position of the joint of the maxillary and mandibular incisor brackets and the presence of distinctive morphological features of the canine and incisor teeth, as well as radiographies of tooth roots, stating that this was unusual. These AM records were supplied by the family of the possible victim, and they consisted of intra- and extra-oral photographs and a panoramic X-ray taken 4 years previously.12

INTERPOL stipulates that everything necessary should be done to create the most complete and up-to-date odontological record possible of a person who has disappeared; to this end, the coordinator of the AM information should contact government and non-governmental agencies to request these data from the victim’s family, their odontologists or medical, academic or military institutions.19 In particular, INTERPOL has designed a specific dental coding system for fixed and removable apparatus,12 and this system has already been applied experimentally for orthodontological components.20 On the other hand, the American Board of Forensic Odontology stipulates that when collecting and storing PM data, the actual procedures to be followed in a case of odontological identification will largely depend on the conditions of the remains.21 The narrative description and nomenclature of the dental file may contain a narrative description of the autopsy findings, with special emphasis on any unusual or unique conditions, such as bands, supports, spacers and orthodontological retainers.21

Good results of comparing dental information in a forensic identification process depend not only on the availability of good quality AM data, but also on the strength of the teeth and dental materials in the PM examination.3 In DOO, the apparatus and materials used have proven their resistance against a range of hazards, so that forensic odontology is able to contribute not only to the identification process, but also to the reconstruction of events in specific cases.22 The metals and alloys used have unique physical properties as well as excellent mechanical characteristics, and they also resist corrosion; in particular, DOO apparatus are usually made of commercially pure titanium, titanium–aluminium–vanadium alloys or with elements made of nickel, molybdenum or copper.23–25 Stainless steel too is widely used in DOO,24,26 and the explosion in cosmetic odontology led to the use of ceramic devices in the speciality.27 All of these materials are well-known for their resistance and durability under extremely hostile conditions,22,28 which has even led to calls for fixed as well as removable apparatus to include identifying marks.28,29

Almeida et al.30 and Feldens et al.31 state that in Brazil almost 65% of adolescents are affected by malocclusions and require corrective orthodontic work, of whom 69% are disposed to undergo DOO treatment. Silva et al. cite the rigorous nature of Brazilian law as the reason why appropriate orthodontological information is available when it is requested for forensic identification.3 Apart from these figures, Brazil has been said to have one of the highest numbers of forensic odontologists in the world.32 Its recognised pre- and post-graduate training in the speciality and successes in the field33 and a more than proven productivity position Brazil among the 20 most scientifically active countries in the world with a higher number of publications in the field of legal medicine, considerably higher than other Latin American countries.34 We believe that the focus of this review illustrates one of the many ways in which Brazil has come to be a deserved leader in the field of legal and forensic odontology, and it also suggests that it is time for a deeper and more critical look at the opportunities in this area for research and productivity.

Clinical files containing records of therapeutic procedures are the most widely available data sources for the identification of human remains, and this prevalence is justified by the need to constantly record steps taken in treatment for precise clinical monitoring. This is more prominent in orthodontic procedures, which have been used more often in recent years for human dental identification due to the increasing popularity and accessibility of DOO, and its radiographic and photographic records which constitute valuable AM information.8,9,12 The usefulness of having appropriate radiological data for identification purposes has been duly reported,19,35 and obtaining intraoral photographs (which are protocol-governed in DOO and a highly useful forensic resource) is now simple and low-cost, without the use of radiation.9 This practice should be re-evaluated throughout dental specialities. This makes it even more necessary for radiographic and photographic resources which support odontological clinical files, as they have higher intrinsic worth for forensic identification.18

ConclusionsAlthough the low number of reports was confirmed, and therefore also a possible under-use of orthodontic records, they are highly useful when establishing the identity of a dead individual. This is because the identification process is aided by the quality and quantity of AM information, as well as by the stability and durability of the orthodontic artefacts present in cadavers, which offer PM information. DOO stands out because it requires that records be updated and kept, including written documents, as sufficient and trustworthy abundance of radiographies, photographs and plaster models which open up a range of technical possibilities in the comparative identification procedure. We suggest promoting the same storage of radiographies and photographs in all odontological clinical activities, regardless of their type of speciality, while also ensuring that regulatory mechanisms exist to recommend this. More specifically for forensic odontologists, we invite them to report their cases, as they represent a matchless opportunity for learning and growth in legal medicine.

FinancingThis research received no specific grant from any public, commercial or not-for-profit agency.

Please cite this article as: Vidal-Parra M, Fonseca GM. Registros ortodóncicos para la identificación forense: una revisión exploratoria. Revista Española de Medicina Legal. 2022;48:78–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reml.2021.08.002.