The social significance of the rights of patients has produced in Spain a diffuse legislative enactment since 2000 that culminated with the drafting of the living will document, or advanced directives. The basis of this document is the recognition of the autonomy of the patient. This respect goes beyond the competencies of the patient by enabling clinical situations to be anticipated and related decisions to be taken in advance.

Living will is a written document that reflects an act of personal responsibility. It is a tool for making clinical decisions that is particularly applicable to chronic patients susceptible of developing cognitive impairment and a state of dependency. Health professionals should be aware of current legislation on the principle of autonomy, and must make their patients aware of the option to implement this procedure. An educational and public awareness campaign aimed at professionals and the general public is required.

La trascendencia social de los derechos de los pacientes ha comportado en España una prolija promulgación legislativa desde el año 2000, que culmina con el desarrollo del documento conocido como testamento vital, de instrucciones previas o de voluntades anticipadas. El fundamento del testamento vital radica en el reconocimiento de la autonomía del paciente. Este respeto va más allá de la situación de competencia del paciente al permitir anticipar situaciones clínicas y sus correspondientes decisiones. El documento de voluntades anticipadas es un documento escrito que refleja un acto de responsabilidad personal, siendo de especial ayuda en enfermos crónicos que pueden evolucionar hacia situaciones de dependencia y deterioro cognitivo. Los profesionales de la salud deben conocer la legislación vigente en materia del principio de autonomía. Resulta esencial que den a conocer a sus pacientes la posibilidad de realizar este procedimiento. Es necesaria una tarea divulgativa y pedagógica ante los profesionales y la población general.

The origin of the so-called living will (LW) or advance directive (AD) stems from the 1969 publication by Luis Kutner of a concept document in which a person may express their wishes with regard to medical treatment in the event of terminal illness.1

Its initial implementation was scant due to the lack of regulatory support. In 1976, however, the scenario changed following the conflict between two parents and a healthcare centre due to the removal of mechanical ventilation from a patient with irreversible brain damage (Karen Quinlan case).2 This led to the constitution of the first hospital ethical committees, and the State of California issued the Natural Death Act that legalised the LW and acknowledged the patient's right to prevent the artificial prolongation of their life.3

In Europe, the first legislation to make reference to the LW is the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being, with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine (Oviedo, 1997),4 which was ratified by Spain and has been effective since 1 January 2000. Article 9 thereof states that “the previously expressed wishes relating to a medical intervention by a patient who is not, at the time of the intervention, in a state to express his or her wishes shall be taken into account”.

Following this Convention, several Spanish autonomous communities regulated the matter individually, albeit without a common deliberation that would guarantee the minimum ethical standards,5 thereby rendering the enactment of a basic state-wide law necessary in order to establish the minimum common contents. Table 1 reflects the different names appearing in the legislation of the autonomous communities, although this article will use the term advance directive (AD).

Different names, according to the autonomous communities.

| Preliminary instructions | Spain, Castile and Leon, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Murcia |

| Advance will | Aragon, Balearic Islands, Castilla-La Mancha, Catalonia, Valencian Community, Navarre, Basque Country |

| Advanced statement of will | Canary Islands |

| Preliminary will | Cantabria |

| Advance expression of will | Extremadura |

| Advance living will | Andalusia |

Law 41/20026 provided the legislative foundations for the implementation of the AD in Spain. Article 11 defines it as “the advance statement by an adult, capable and free person of their will as they wish it to be observed in the event of circumstances in which they are unable to personally express their wishes regarding their health care and treatment or, following their death, regarding what is to be done with their body or organs”, thus reflecting the patient's or citizen's will if they are incapable taking their own decisions.

In Spain, the related jurisprudence is virtually non-existent. Mention should be made here of the order by the Provincial Court of Lleida, Penal Section 1 (no. 28/2011 of 25 January), which resolved a previous ruling against which an appeal had been brought, regarding the performance of a blood transfusion. The patient, a Jehovah's witness, told their attending physician, and had also stated in a duly registered AD, that they did not wish to have a blood transfusion even if their hypothetical condition rendered one necessary. In this case, and although several rulings by the Constitutional Court of Spain have described human life as a fundamental value that prevails over the freedom and ethics of the individual, the judge found that, taking into account that the only exceptions to consent will be when there is a risk to public health and when there is an immediate and serious risk to the patient's physical and mental health and it is impossible to secure the consent of the patient or their relatives, “the clear and unequivocal will expressed by the patient” had to prevail since, according to the Supreme Court, informed consent is a fundamental human right.

Bioethical principlesConsidering the patient as a moral subject, bioethics deals with human behaviour in medicine and health, taking their values and moral principles into account.7

The principles of modern bioethics were first formulated explicitly in 1978 in the Belmont report. These principles were to govern research on human beings and clinical and health care practice in medicine.8 The ethical foundation of the AD is based on the respect for and promotion of patient autonomy, which is prolonged by the AD when the patient can no longer decide for themselves. It must be understood as an example of citizens’ interests and responsibility in decisions relating to their health. It involves the recognition of the patient's desires and values to influence any future decisions that may affect them, guaranteeing the respect for these values when their clinical condition does not allow them to express them personally.9,10

The writing of an AD calls for ethical competence, i.e. the capacity to reflect freely and responsibly about how the citizen wishes to be treated when they are dying or in a situation of illness or disease where they cannot express their own will. Everyone is presumed to have this ethical competence as long as there are no reasons to doubt it. However, there are borderline situations in which the medical team may have reasonable doubts as to the degree of a person's ethical competence. In such situations, it is very difficult to accurately define whether they have the capacity to deliberate and anticipate consequences.11 Scales of ethical competence are intended to help the medical team ascertain a person's real degree of autonomy. When signing an AD, the minimum conditions of personal autonomy must be guaranteed, which include accurate information on the possibilities available to the person, an understanding of the same and their possible consequences, and the absence of both external and internal coercion.8

When ethical competence is attributed to a person who is unable to decide for themselves, a defect in autonomy is incurred. However, when a person is denied the competence to decide freely and responsibly, despite being able to do so, paternalism is incurred, which is much more widespread than the former in Mediterranean countries. The right to information, informed consent and advance directives are regarded as the three cornerstones on which the respect for a person's autonomy rests. With these three pillars, the relationship between the healthcare professional and user is no longer dominated by the medical paternalism that previously characterised a large part of the history of healthcare.8

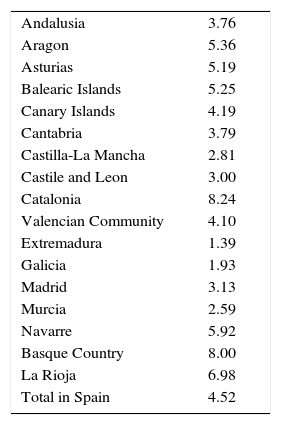

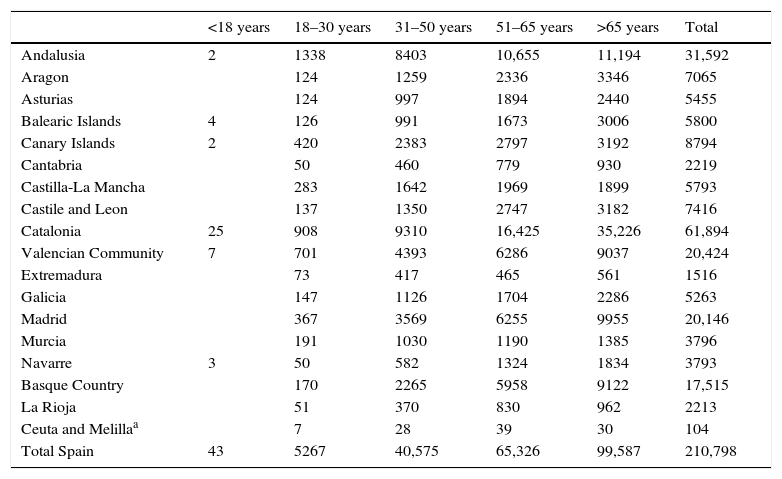

The implementation of the advance directive document in SpainUnlike English-speaking countries, in general, the implementation of the AD in Spain is very low (Table 2), with a global incidence of 4.52 per 1000 inhabitants, with implementation increasing in parallel to age (Table 3).

Declarants with an active advance directive by AC in 2015, per 1000 inhabitants.

| Andalusia | 3.76 |

| Aragon | 5.36 |

| Asturias | 5.19 |

| Balearic Islands | 5.25 |

| Canary Islands | 4.19 |

| Cantabria | 3.79 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 2.81 |

| Castile and Leon | 3.00 |

| Catalonia | 8.24 |

| Valencian Community | 4.10 |

| Extremadura | 1.39 |

| Galicia | 1.93 |

| Madrid | 3.13 |

| Murcia | 2.59 |

| Navarre | 5.92 |

| Basque Country | 8.00 |

| La Rioja | 6.98 |

| Total in Spain | 4.52 |

Declarants with an active advance directive by age group in 2015.

| <18 years | 18–30 years | 31–50 years | 51–65 years | >65 years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | 2 | 1338 | 8403 | 10,655 | 11,194 | 31,592 |

| Aragon | 124 | 1259 | 2336 | 3346 | 7065 | |

| Asturias | 124 | 997 | 1894 | 2440 | 5455 | |

| Balearic Islands | 4 | 126 | 991 | 1673 | 3006 | 5800 |

| Canary Islands | 2 | 420 | 2383 | 2797 | 3192 | 8794 |

| Cantabria | 50 | 460 | 779 | 930 | 2219 | |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 283 | 1642 | 1969 | 1899 | 5793 | |

| Castile and Leon | 137 | 1350 | 2747 | 3182 | 7416 | |

| Catalonia | 25 | 908 | 9310 | 16,425 | 35,226 | 61,894 |

| Valencian Community | 7 | 701 | 4393 | 6286 | 9037 | 20,424 |

| Extremadura | 73 | 417 | 465 | 561 | 1516 | |

| Galicia | 147 | 1126 | 1704 | 2286 | 5263 | |

| Madrid | 367 | 3569 | 6255 | 9955 | 20,146 | |

| Murcia | 191 | 1030 | 1190 | 1385 | 3796 | |

| Navarre | 3 | 50 | 582 | 1324 | 1834 | 3793 |

| Basque Country | 170 | 2265 | 5958 | 9122 | 17,515 | |

| La Rioja | 51 | 370 | 830 | 962 | 2213 | |

| Ceuta and Melillaa | 7 | 28 | 39 | 30 | 104 | |

| Total Spain | 43 | 5267 | 40,575 | 65,326 | 99,587 | 210,798 |

With respect to the use of the same, Llordés et al. stated that only 2% of the population has formalised an advance directive, although 38% said that they have heard of it.12 As for target groups, in patients with chronic diseases, although an improvement in the knowledge of disease evolution has been ascertained, ignorance regarding the LW and the scant predisposition to having one drawn up persist.13 ADs are used more in chronic diseases; patients with COPD14 or the HIV-infected population.15 In mental health, the use of the AD even increases trust in the doctor-patient relationship.16

The patient's loved ones are usually unaware of the advance directive, although there does tend to be great interest in it. When the time comes, the absence of an AD generates great concern in the patient's family environment, as relatives feel burdened with the responsibility to make decisions on his/her behalf, and a consensus is not always reached between family members with regard to what should be done, which in turn generates anxiety, uneasiness and even guilt. For this reason, greater attention to psychosocial and emotional issues is important for quality end-of-life care,17 and this includes information about the AD. It would thus be very useful to increase information in this regard, particularly in the sphere of primary medicine.18

Primary healthcare constitutes an ideal situation for guiding and advising the patient about preparing and registering the AD.19 Llordés et al. stated that 74% of primary care patients evince an interest in receiving information, and that most of them (59%) wish to have it in writing. However, in the group of over-65s, the preference for a personalised approach predominates, in the form of chats and/or interviews with the healthcare staff.12 Dissemination activities regarding the AD should also encompass the steps to be followed in order to formalise one, since they may be different in each setting.12

A greater involvement is required on the part of healthcare professionals in helping with the advanced planning of care and the drafting of the AD.20 It should be remembered that having an AD does not entail a restriction on subsequent healthcare or impose any limit upon the treatment possibilities that should be offered.21 The attitude of professionals to the AD is by no means homogeneous and varies depending on speciality, experience and personal beliefs. One of the most visible dangers for the specialist physician is reducing the complexity of the human phenomenon and addressing it exclusively from the perspective of an organ or system.22 However, certain specialities evince a particular awareness in accordance with the object of their practice. Thus, in percentage terms, transplant specialists are the professionals who refer most to the patient's medical history to enquire about the existence of an AD.23

Generally speaking, most professionals do not know if the patient for whom they are responsible has an AD. Moreover, some professionals, despite knowing, would not observe it in the event of a life-threatening emergency, hence the undeniable need for greater training in this regard.24,25 The involvement of administrations, patients, relatives and, above all, doctors is necessary in order to improve the penetration of this type of document within the group.26

Formalisation and access to the advance directive by the physicianRegarding the specific procedure through which the AD is formalised, it may be drawn up in the presence of a notary public, and in some Spanish communities, it may be executed before an administrative civil servant or three adult witnesses with full mental capacity. At least two of these witnesses should not have a kinship relationship up to the second degree, and cannot be involved in any way with the executor's estate. Formalisation by means of registration in the official registers of the different autonomous communities is advised.27

Royal Decree 124/2007, of 2 February,28 regulates the Spanish National Register for Advance Decisions (RNIP) and the corresponding automated personal data file. This includes the creation of the register, its dependence on the Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs (now the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality), its object and purpose, the registration and access procedure and the mandate for the creation of the corresponding automated file.

Healthcare physicians may consult the Register for Advance Decisions electronically when they encounter patients whose physical or mental condition prevents them from making decisions by themselves. Enquiries are made by guaranteeing the proper authentication of the professional and the respect for privacy and confidentiality. The routes of access for the different autonomous communities can be found on the Ministry's website (http://www.msssi.gob.es/ciudadanos/rnip/doc/Registrosautonomicosipfinal.pdf).

In our opinion, this AD registration channel is the only one to guarantee proper access to patients and professionals when they need it. Other possibilities acknowledged by the law, such as the execution of the same in the presence of witnesses or a notary public, must be followed by the entry of the AD in the Register in order to guarantee access to it in case of an unexpected event. This does not preclude the possibility of the patient or his/her family providing the referring physicians with the document or having it added to the patient's medical history.

Contents of the advance directiveThe AD cannot contain provisions that are contrary to the legal ordinance and which do not fulfil good clinical practice (lex artis), nor those that do not correspond exactly to the event envisaged when the AD was executed.6 Finally, the AD can be repealed or amended at any time.

If we consider the AD as the instructions given by the citizen/patient to their physician or healthcare team, in which they state the type of medical care they wish to receive at the end of their life and where they can appoint a person to represent them in the event they are unable to express any decisions that may correspond to them, the document should address the following aspects:

- a)

Personal values to help guide physicians when making clinical decisions.

- b)

Instructions regarding the care and treatment they do or do not want to receive.

- c)

Their decision pertaining to organ or body donation.

- d)

The appointment of a representative to liaise with the healthcare team.

As such, it would be useful for the patient's referring physician or other healthcare professionals to collaborate in the drafting of the document. In line with this, and albeit different to the AD, a new and highly useful tool has emerged in the healthcare provided to patients with chronic conditions, which is known as “advance decision planning”. This corresponds to the process of exploring and identifying the patient's values, preferences and objectives in order to establish suitable objectives and measures, pre-empting foreseeable scenarios or situations in terms of the patient's evolution. Anticipating advance decisions requires a qualitative, evolution-based, gradual, voluntary and unforced, confidential process which is subject to continual review and used with competence, respect and confidence. Moreover, the involvement of the family can also be advisable on certain occasions.

ConclusionsThe advance directive is a written document that reflects a legal and ethical right based on the respect for patient autonomy. Although people in Spain are generally unaware of the tool, which is scarcely implemented as a result, it is nevertheless a clinical decision-making tool that may prove particularly helpful in chronic patients who may course towards situations of dependence and cognitive impairment.

Healthcare professionals must be conversant with the applicable legislation on matters regarding the principle of patient autonomy, and have a legal and ethical responsibility to guarantee both patient protection, in the event of vulnerability, and the utmost respect for the patient's autonomy. Consequently, a greater effort in disseminating and teaching this principle to healthcare professionals, the administrations and the general public is required. Similarly, physicians must inform their patients of the possibility to execute this procedure and must include information about the AD as an essential part of the doctor-patient relationship.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Arimany-Manso J, Aragonès-Rodríguez L, Gómez-Durán E-L, Galcerán E, Martin-Fumadó C, Torralba-Rosselló F. El testamento vital o documento de voluntades anticipadas. Consideraciones médico-legales y análisis de la situación de implantación en España. Rev Esp Med Legal. 2017;43:35–40.