B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) is an anti-apoptotic protein that may play a role in disordered proliferative endometrium (DPE) and endometrial hyperplasia (EH). Several studies have investigated BCL-2 expression in normal, hyperplastic endometrium and endometrial adenocarcinoma, with conflicting results. Therefore, the present study aimed to compare the expression of BCL-2 in disordered proliferative endometrium and simple EH.

MethodsIn this cross-sectional study, 63 DPE and 67 SEH samples from patients referred to Mostafa Khomeini Hospital between 2017 and 2022 were immunohistochemically stained by BCL-2 antibody. BCL-2 expression in each sample was reported as negative, weak positive, and strong positive. The findings were analyzed using SPSS version 16 software.

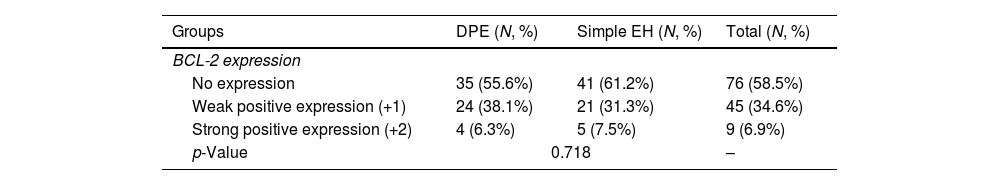

ResultsNegative, weakly positive, and strongly positive BCL-2 expression was observed in 55.6%, 38.1%, and 6.3% of DPE samples, and 61.2%, 31.3%, and 7.5% of SEH samples, respectively, which does not show a statistically significant difference (p=0.718). There was no relationship between the age of patients and BCL-2 expression in any of the two groups of DPE and SEH (p=0.378 and p=0.178, respectively).

ConclusionBCL-2 expression is observed with a relatively similar frequency in DPE and SEH samples, and it is probably under the control of oestrogen hormone as the main factor involved in the pathogenesis of these lesions.

El linfoma de células B2 (BCL-2) es una proteína antiapoptótica que puede desempeñar un papel en el endometrio proliferativo desordenado (EPD) y en la hiperplasia endometrial (HE). Varios estudios han investigado la expresión de BCL-2 en el endometrio normal, en el hiperplásico y en el adenocarcinoma de endometrio, con resultados contradictorios. Por lo tanto, el objetivo del presente estudio fue comparar la expresión de BCL-2 en el endometrio proliferativo desordenado y la hiperplasia endometrial simple.

MétodosEn este estudio transversal se tiñeron inmunohistoquímicamente 63 muestras de EPD y 67 muestras de HE de pacientes remitidas al Hospital Mostafa Khomeini entre 2017 y 2022 con anticuerpos BCL-2. La expresión de BCL-2 en cada muestra se informó como negativa, débilmente positiva y fuertemente positiva. Los hallazgos se analizaron utilizando el programa SPSS versión 16.

ResultadosSe observó expresión negativa, débilmente positiva y fuertemente positiva de BCL-2 en el 55,6%, el 38,1% y el 6,3% de las muestras de EPD, y en el 61,2%, el 31,3% y el 7,5% de las muestras de HE, respectivamente, lo que no muestra una diferencia estadísticamente significativa (p=0,718). No hubo relación entre la edad de las pacientes y la expresión de BCL-2 en ninguno de los dos grupos de EPD y HE (p=0,378 y p=0,178, respectivamente).

ConclusiónLa expresión de BCL-2 se observa con una frecuencia relativamente similar en las muestras de EPD y HE, y probablemente esté bajo el control de la hormona estrógeno como el principal factor que interviene en la patogénesis de estas lesiones.

Among proliferative conditions of the endometrium, there is a morphological sequence that includes disordered proliferative endometrium (DPE), simple and complex endometrial hyperplasia (EH) with and without atypia, differentiated adenocarcinoma, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.1 DPE is a benign disease characterized by structural changes caused by continuous stimulation by oestrogen. One of the characteristics of this disorder is the presence of enlarged glands with an irregular or cystic shape and a relatively normal ratio of the gland to the stroma.2 In EH, estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium causes proliferative changes in the glandular epithelium, including their regeneration and formation of glands with a different shape and irregular distribution. Based on the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1994, EH is divided into four groups: simple and complex EH without atypia and atypical based on the structural complexity of the glands and nuclear atypia.3

Proteins expressed by genes such as proliferating antigens, cytokeratins, and interleukins are used as biomarkers to investigate the pathogenic mechanisms of various malignancies.4–6 The B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) gene is the first gene known to inhibit apoptosis in many cell systems.7 Since the BCL-2 gene can increase the proliferative activity of glandular endometrium,8 it may gradually lead to EH and possibly neoplasia. Several studies have investigated BCL-2 expression in normal and hyperplastic endometrium and endometrial adenocarcinoma, with conflicting results. Some investigators have shown an increased expression of BCL-2 in endometrial carcinoma, especially in low-grade endometrioid types,9,10 while others have reported a decreased expression of this marker in endometrial carcinomas.11,12 On the other hand, due to the use of targeted anti-BCL-2 treatments in breast and ovarian tumours and leukaemia, investigating the expression of BCL-2 in one of the most common gynaecological disorders, namely EH, as a premalignant lesion for endometrial carcinoma is of increasing importance.13

One of the challenges of pathologists in diagnosing endometrial proliferative lesions is the differentiation between non-neoplastic proliferative endometrium and simple hyperplasia.14 The lack of accepted criteria for diagnosing hyperplasia has created multiple classifications for EH, making the diagnosis challenging.15 In any case, finding molecular biomarkers related to EH can help diagnose and understand the mechanisms that initiate the pathogenesis of this disease. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate and compare the expression of oncoprotein BCL-2 in simple EH with benign proliferative endometrial disorder to investigate the possible role of BCL-2 in the development of simple EH, which can be a precursor to the development of endometrial carcinoma.

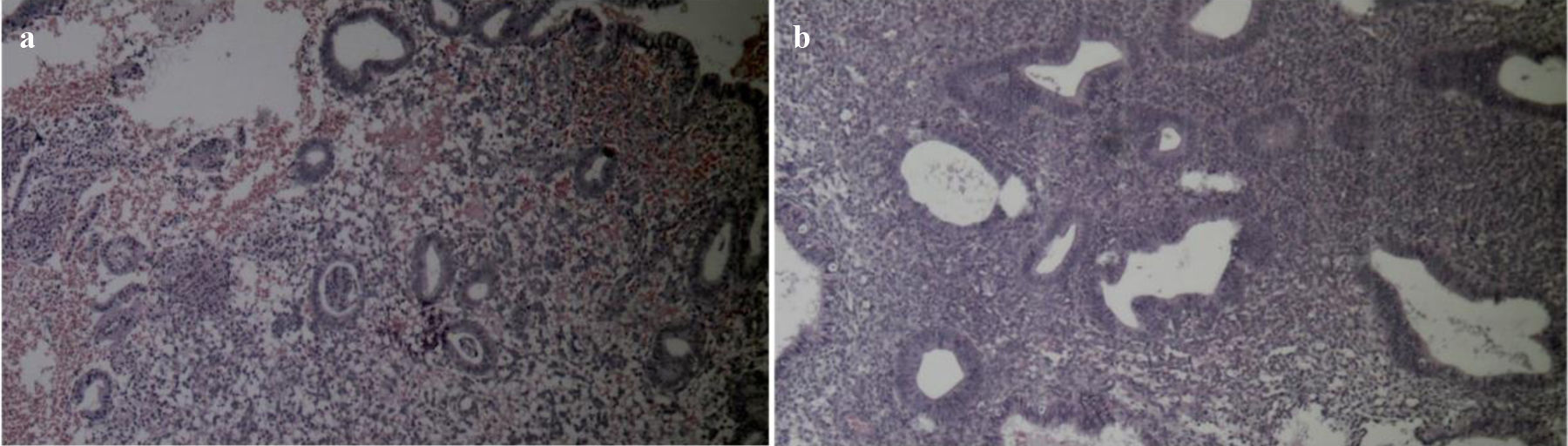

Material and methodsPatients and sample collectionTo carry out this cross-sectional and retrospective study, by searching the database of the pathology department of Mostafa Khomeini Hospital in Tehran, all the samples with the final diagnosis of simple EH or DPE obtained from diagnostic biopsy, therapeutic endometrial curettage, and hysterectomy, during the years 2017–2022, were identified. These samples included 63 samples of DPE and 67 samples of simple EH. The age of each patient was obtained from clinical files archived at the pathology department. Then, the paraffin blocks fixed in formalin stained with the H&E method were reviewed by a pathologist (Fig. 1), and, in addition to confirming the diagnosis, the blocks with minimal necrosis and bleeding with sufficient numbers of endometrial cells were selected for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining. The diagnosis of simple EH was approved based on the criteria of the WHO.2 DPE was also proposed based on the presence of irregular and cystic glands that were focally located among normal proliferative glands.16 Samples that did not have enough tissue for staining or whose files were incomplete were excluded from the study.

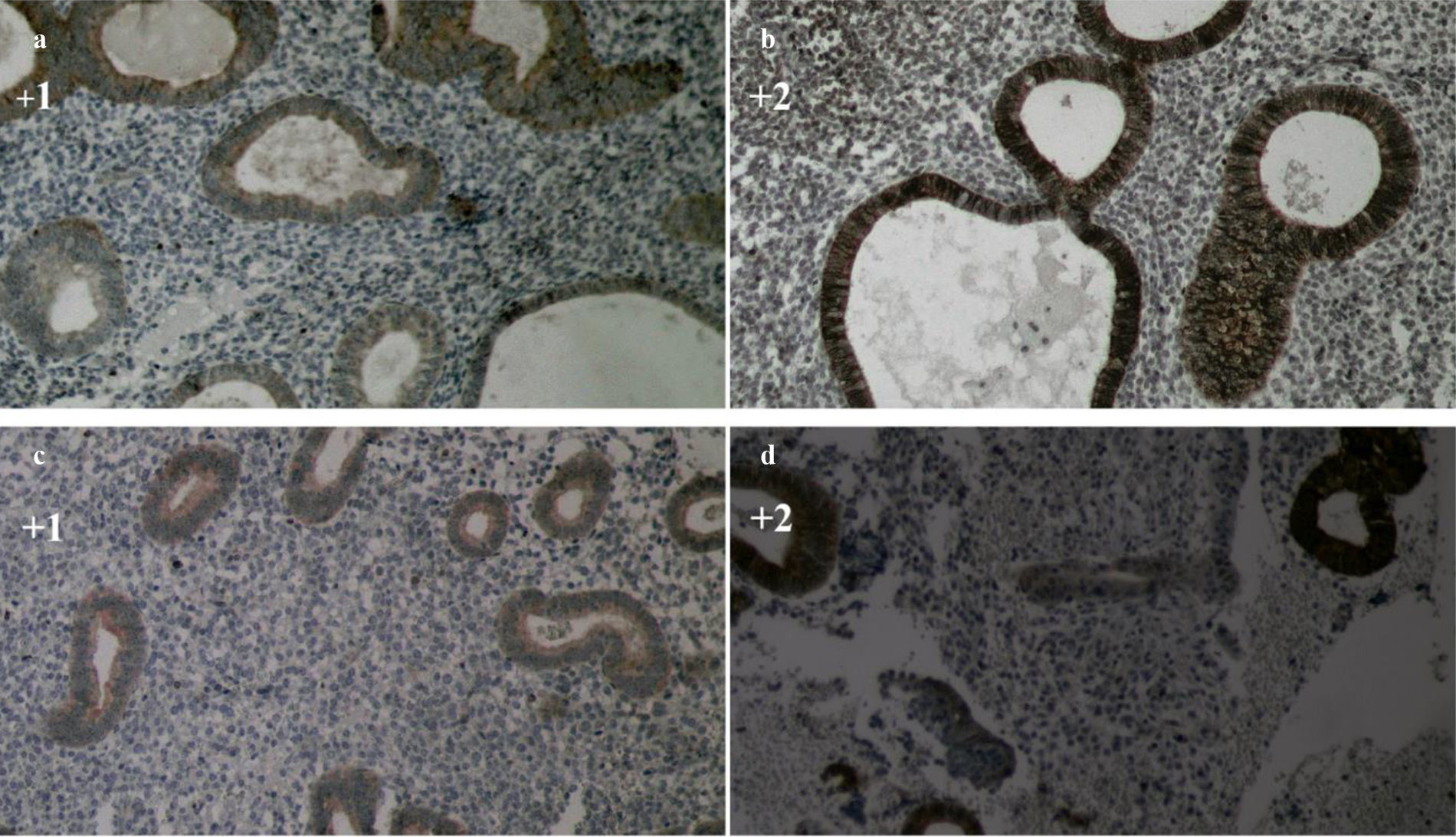

Immunohistochemical studiesFirst, a tissue section with a thickness of 4 microns was prepared using a microtome device from each paraffin block fixed in formalin. IHC staining was performed based on the BCL-2 laboratory kit staining instructions (Biogenex USA). Finally, slides stained by IHC were observed by a pathologist, who was not aware of the clinical characteristics of the samples, using a light microscope at 40× magnification. The expression of BCL-2 was semi-quantitatively determined based on the intensity and extent of staining in endometrial epithelial cells in DPE and simple EH samples as follows: 0=no colour acceptability, +1=weak positive staining, +2=strong positive staining.7

Statistical analysisThe collected data was entered into SPSS version 16 statistical software (IBM SPSS Statistics, New York, United States) and analyzed by this software. Qualitative and quantitative descriptive data were expressed as frequency percentages and mean±standard deviation, respectively. Appropriate statistical tests, including Chi-square, Mann–Whitney, and Pearson correlation, were used to analyze the data and check the statistical relationship between the expression intensity of BCL-2 in DPE and simple EH and its relationship with the age of the patients. The statistical significance threshold was p<0.05.

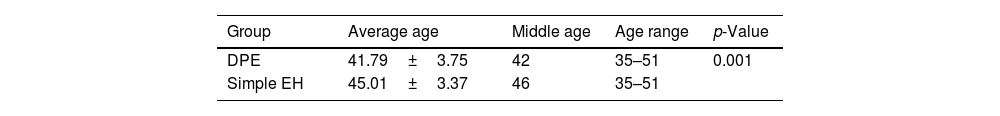

ResultsIn this study, a total of 130 samples, including 63 samples of DPE and 67 samples of simple EH, were examined. The average age of all patients was 43.45±3.9 years and ranged from 35 to 51 years, which is shown in Table 1. The average age of patients with simple EH is significantly higher than patients with DPE (p=0.001).

The IHC expression of the BCL-2 marker in the simple EH samples was 61.2%, 31.3%, and 7.5% for no expression, weak positive expression (+1), and strong positive expression (+2), respectively (Fig. 2, a and b). Also, the expression of this marker in the DPE samples was 55.6%, 38.1%, and 6.3% for no expression, weak positive expression (+1), and strong positive expression (+2), respectively (Fig. 2, c and d). The expression frequency of this marker in each group is shown in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of BCL-2 expression in the two groups of DPE and simple EH (p=0.718).

Comparison of BCL-2 expression in DPE and simple EH.

| Groups | DPE (N, %) | Simple EH (N, %) | Total (N, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCL-2 expression | |||

| No expression | 35 (55.6%) | 41 (61.2%) | 76 (58.5%) |

| Weak positive expression (+1) | 24 (38.1%) | 21 (31.3%) | 45 (34.6%) |

| Strong positive expression (+2) | 4 (6.3%) | 5 (7.5%) | 9 (6.9%) |

| p-Value | 0.718 | – | |

N: number, %: percentage, DPE: disordered proliferative endometrium, simple EH: simple endometrial hyperplasia.

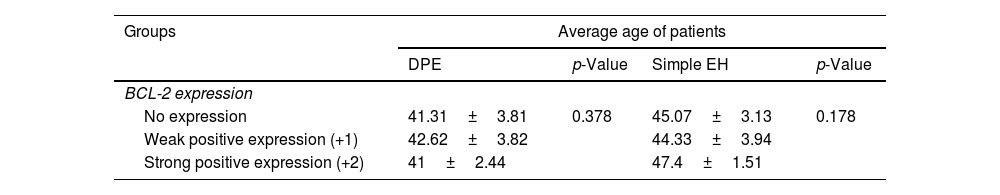

The relationship between BCL-2 expression and the age of patients was investigated and did not show a statistically significant relationship in any of the two groups of DPE (p=0.378) and simple EH (p=0.178), as shown in Table 3.

Relationship between age and BCL-2 expression in DPE and simple EH.

| Groups | Average age of patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPE | p-Value | Simple EH | p-Value | |

| BCL-2 expression | ||||

| No expression | 41.31±3.81 | 0.378 | 45.07±3.13 | 0.178 |

| Weak positive expression (+1) | 42.62±3.82 | 44.33±3.94 | ||

| Strong positive expression (+2) | 41±2.44 | 47.4±1.51 | ||

DPE: disordered proliferative endometrium, simple EH: simple endometrial hyperplasia.

In the present study, the expression of BCL-2 was investigated using the IHC method in tissue samples of DPE and simple EH. Based on the findings of this study, BCL-2 expression was detected in 44.4% of DPE samples and 38.8% of simple EH samples (weak positive and strong positive). Also, the strong expression of this marker was present only in 6.3% of proliferative DPE samples and 7.5% of simple EH samples, which does not show a statistically significant difference between the two investigated groups. In the study by Cinel et al., the positive expression of BCL-2 was observed in 87.5% of DPE samples (7 cases out of 8 samples).17 In another study conducted by Morsi et al., BCL-2 expression was observed in all samples of DPE (6 cases), which in most samples was between 1% and 5% of epithelial cells.16 The positive expression of BCL-2 in both studies mentioned is higher than in our study. Although, these two studies examined a limited number of DPE samples, which can be effective in these results. Also, the scoring method of BCL-2 expression in these two studies was semi-quantitative and based on the percentage of expression of this marker in epithelial cells. In contrast, in the present study, we considered the intensity of BCL-2 staining in cells. In the study by Cinel et al., the positive expression rate of BCL-2 in simple EH samples was reported to be 45.5%, which was lower than DPE, but this difference was not statistically significant.17 In the study by Morsi et al., BCL-2 expression was present in 92% of simple EH samples, which did not show a statistically significant difference with DPE samples.16 The findings of our study are consistent with those of these two studies, indicating no difference in BCL-2 expression in simple EH and DPE. The expression of BCL-2 in the basal layer of the endometrial glands in the DPE, which has been shown in previous studies, suggests the increased life of these cells.16 The systematic review study findings revealed that there is no significant difference in BCL-2 expression levels between proliferative endometrium and benign hyperplasia.18

Most of the studies conducted in the field of examining BCL-2 in endometrial lesions have examined the expression status of this marker in endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia samples, which have been associated with different results. In the study by Laban et al., who used a grading system similar to our study to report BCL-2 expression, strong BCL-2 expression was observed in only 8.5% of cases of simple EH, which is close to the results of our study.7 BCL-2 expression was negative in 83% of simple EH cases and 80% of DPE samples in this study.7 The study by Mourizikou et al. also showed that BCL-2 expression is more common in low-grade carcinomas.9 In the study of Marone et al., which was done using western blot, the expression of BCL-2 in neoplastic endometrium is more common than in normal endometrium.10 Also, some studies have shown that the expression of BCL-2 decreases in the transition from EH to endometrial carcinoma.19,20 The reason for this is probably that the BCL-2 protein is inactivated and its expression is reduced in a transformed cell that has acquired a malignant phenotype through cellular mechanisms. At the same time, BCL-2 expression inhibits growth in endometrial carcinoma cell lines and solid tumour cells.21 The difference in the grade and degree of differentiation of the carcinoma samples in different studies can influence the difference observed in the results of the above studies. In the study by Kokawa et al., the expression of BCL-2 protein in atypical EH samples (36.2%) was significantly lower compared to non-atypical hyperplasia (16.3%).22 In the study conducted by Nunobiki et al., it was found that there was no significant difference in the percentage of BCL-2 expression between normal proliferative endometrium (65.32%), simple non-atypical hyperplasia (59.58%), and complex hyperplasia (60.4%).20 However, in the samples of atypical hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma, there was a significant decrease in BCL-2 expression,20 but some studies have shown that the expression of BCL-2 between simple and complex endometrial lesions as well as atypical and non-atypical lesions did not show a significant difference.23,24 The results of the study by Hassan et al. showed that non-malignant endometrial lesions express higher levels of BCL-2 compared to malignant endometrial lesions, and the expression of BCL-2 in glandular epithelium in hyperplasia samples was significantly higher than in carcinoma samples.23

According to the previous hypotheses, it seems that the expression of BCL-2 in the endometrial tissue is under hormonal control. If the expression of BCL-2 in the endometrium is regulated by the levels of oestrogen and progesterone, then the increased levels of oestrogen in patients with EH and some cases of endometrial carcinoma may be caused by hyperplasia lead to increased expression of BCL-2.25,26 BCL-2 expression is expected to be high in benign proliferative conditions caused by oestrogen action, such as proliferative endometrium and benign EH.19,25,26 The results of the study by Deger et al. showed that BCL-2 expression has a positive correlation with progesterone receptors in non-atypical hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma samples.27 This study concluded that positive expression of BCL-2 and progesterone receptors is associated with good prognosis in endometrial carcinoma.27 In the study by Mitselou et al., the expression of BCL-2 was related to the expression of progesterone receptors in EH samples.28 The results of the study by Hassan et al. also showed that there is a positive correlation between the expression of BCL-2 and the expression of oestrogen and progesterone receptors in endometrial carcinoma.23 On the other hand, the administration of progesterone has led to a decrease in BCL-2 expression in EH and endometrial carcinoma and the reduction of BCL-2 expression is a potential marker for the efficacy of progesterone treatment in EH.29 Wu et al. showed that the expression of BCL-2 protein in the normal endometrium of women is periodic and is significantly higher in the proliferative phase than in the secretory phase.30 Also, BCL-2 expression in EH tissue had a positive correlation with oestrogen and progesterone receptors.30 These results confirm the role of oestrogen and progesterone hormones in regulating BCL-2 expression in endometrial tissue, which can play a role in the pathogenesis of EH. It may be concluded that in the early stages of endometrial carcinogenesis, which is accompanied by EH, oestrogen increases the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL-2, and by prolonging the life of cells, it leads to the accumulation of genetic abnormalities in them for subsequent malignant changes.31 The results of the study by Laban et al. also reported an essential role for BCL-2 as a trigger for the initiation of endometrial carcinoma, but the expression of this marker was not associated with subsequent tumour progression.7 Perhaps when a malignant phenotype develops, cancer cells may lose responsiveness to oestrogen and express low levels of BCL-2. Also, another study reported that changes in the expression of BCL-2 and PAX2 proteins occur in the early stages of endometrial tumour development and are usually seen as an increase in BCL-2 expression and a decrease in PAX2 expression at the same time.32 In our study, considering that the pathogenesis of DPE lesions and simple EH are usually related to the increased secretion of oestrogen and accompanied by cell proliferation, it seems that the expression of BCL-2, which is under hormonal control, does not show a significant difference in the two lesions.

A succession of genetic alterations is imperative for the development of EH and its progression to endometrioid carcinoma. Nevertheless, the precise genetic mechanisms involved in this progression remain incompletely elucidated.33 Microsatellite instability represents one of the genetic mutations detected in approximately 30% of sporadic endometrial malignancies.34 Moreover, mutations and inactivation of various oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes like Her-2, C-myc, PTEN, K-ras, and P53 have been reported in cases of endometrial cancer.35 Nonetheless, except for PTEN mutations observed in around 40% of sporadic endometrial carcinomas, the incidence of other genetic mutations is relatively low. This suggests that other genes may play a key role in the progression to endometrial carcinoma.33 Apoptosis or programmed cell death is a physiological mechanism that provides the necessary mechanisms for the elimination of cells and keeps the number of cells in different organs at a normal level.7 Apoptosis is involved in the cystic development of normal endometrium tissue.8–10 The process of apoptosis is controlled by several genes, the most important regulator of this process is the BCL-2 gene.26 The BCL-2 gene was the first gene of the BCL-2 family that was identified as an inhibitor of apoptosis. The BAX gene is another member of the BCL-2 family, which has an apoptosis-stimulating function.36 BCL-2 family genes can form homodimers or heterodimers with each other. The pro-apoptotic activity of the BAX protein is dependent on the formation of BAX homodimers on the mitochondrial outer membrane. The antagonistic effect of the BCL-2 protein is due to its ability to form BCL2-BAX heterodimers, which prevents the formation of BAX homodimers.37 For this reason, it has been suggested that the ratio of BCL-2 to BAX is a key factor for regulating apoptosis, so a higher ratio of BCL-2 to BAX makes cells resistant to apoptotic stimulation, while a lower ratio induces cell death.38 Therefore, the mentioned contents indicate a possible role of the BCL-2 gene in the development of some neoplasms.

Apoptosis is involved in the normal process of endometrial shedding that occurs with menstruation. Therefore, inhibition of apoptosis seems to play an important role in the development of neoplasia. As previously mentioned, excessive oestrogen leads to uncontrolled proliferation of endometrial cells. BCL-2 expression is regulated by oestrogen secretion, peaking during the proliferative phase and decreasing during the secretory and menstrual phases.39 Since the BCL-2 gene may increase the proliferative activity of the glandular endometrium, it may gradually lead to endometrial hyperplasia and possibly neoplasia.8 Some studies have shown that long-lived BCL-2-positive cells are more likely to accumulate the genetic abnormalities necessary to become malignant. In addition, in vitro studies have shown that overexpression of BCL-2 plays an important role in epithelial tumour development and causes the progression of endometrial hyperplasia to malignancy.17 Also, one study has suggested that lack of BCL-2 expression in endometrial hyperplasia may be a new indication for treatment when precancerous features are ambiguous on histological examination.18 Also, cases of significant reduction of BCL-2 expression in endometrial hyperplasia have been reported, which cannot be interpreted according to the available scientific information.40 However, the exact role of BCL-2 expression in endometrial carcinogenesis is not clear, and the clinical use of this marker in the differential diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia is still under discussion. On the other hand, targeted anti-BCL-2 treatments have been used in breast, ovarian, small-cell lung carcinoma, and leukaemia, which highlights the importance of examining BCL-2 expression in endometrial hyperplasia, as a premalignant lesion for endometrial carcinoma.13

According to the findings of our study, the average age of patients with simple EH was significantly higher than patients with DPE. So, the mean and median age of patients with simple EH was 4 years more than patients with DPE. EH is often the result of the development of a DPE, which, if left untreated, in some cases progresses to neoplasia as the patient ages.1 The results of studies have shown that the average age of onset of EH is often between 40 and 50 years old, and the average age of diagnosis of simple and atypical EH is reported to be 51 years and 56 years, respectively.41 The results of another study showed that the maximum incidence of simple and complex EH in women is between the ages of 50 and 54 and atypical hyperplasia between the ages of 60 and 64.42 Based on the results of our study, there was no statistically significant relationship between the age of patients and BCL-2 expression in any of simple EH and DPE, which shows that the regulation of BCL-2 expression in endometrial cells in the mentioned lesions is independent of the age of the patients. Unfortunately, in none of the previous studies the relationship between BCL-2 expression and age in patients with benign EH has been investigated, so it is necessary to conduct more studies in this field.

LimitationIn the present study, samples of atypical hyperplasia as a premalignant lesion and endometrial adenocarcinoma were not investigated, and the results of the present study are limited to benign endometrial lesions. Future research could consider exploring the relationship between BCL-2 expression and endometrial adenocarcinoma/atypical hyperplasia to further elucidate potential associations of BCL-2 expression with disease progression and clinical implications. The absence of control cases of endometrial carcinoma and normal endometrium in the study presents a limitation in fully assessing the expression of BCL-2. We acknowledge the limitation of the small sample size in this study and encourage further research with more extensive samples to confirm and expand upon our findings. Also, in this study, the IHC method was used, which examines BCL-2 at the level of protein expression, and to examine its expression at the gene level, molecular studies are needed. A more detailed examination of BCL-2 expression at the gene level requires more studies.

ConclusionBased on the results of our study, the expression of the BCL-2 marker is observed with a relatively similar frequency in the DPE and simple EH samples. The expression of BCL-2 in the samples of DPE and simple EH was not statistically significant. BCL-2 expression in DPE and simple EH is independent of patients’ age. Because most of the examined samples lacked BCL-2 expression, more studies should be conducted to compare the expression of this marker with normal endometrium and endometrial carcinoma to draw definitive conclusions in this field.

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahed University (IR.SHAHED.REC.1401.056).

FundingFunded by Shahed University of Tehran.

Authors’ contribution (Authorship)Z.G. and M.J.N. extracted data and samples were reviewed by M.J.N. The statistical analysis was done by M.S. The initial draft was written by M.S. and Z.G., which was finalized by M.J.N.

Informed consentAll patients in the study had written informed consent in their files for using their file information and tissue samples for research purposes.

Conflict of interestsNone.

We would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research of the Shahed University of Tehran for approving and financially supporting the research.