Paracoccidioidomycosis is a neglected tropical disease caused by fungi of the genus Paracoccidioides. A wide range of symptoms is related to the disease; however, lungs and skin are the sites predominantly affected. The disease is mostly seen in people living in rural areas in Latin America.

Case reportWe present a pediatric case of severe disseminated paracoccidioidomycosis that slowly responded to the antifungal treatment. Within three months, symptoms evolved into hepatosplenomegaly, necrotic cervical and abdominal lymph nodes, and splenic abscess. Clinical response to amphotericin B deoxycholate and itraconazole was slow, resulting in pleural and peritoneal cavity effusions, heart failure and shock. Amphotericin B deoxycholate was replaced by the liposomal formulation, with no response. Subsequently, prednisone was added to the treatment, which led to improvement in the clinical response. Serological Paracoccidioides antibody titers were atypical, with very low titers in the critical phase and significant increase during the convalescence phase. The infection was finally cleared up with amphotericin B deoxycholate, liposomal amphotericin B and the use of corticosteroids. Paracoccidioidomycosis serology was non-reactive two years post-discharge.

ConclusionsDue to the intense inflammatory response triggered by Paracoccidioides cells, giving low-dose prednisone for a short period of time modulated the inflammatory response and supported antifungal treatment.

La paracoccidioidomicosis es una enfermedad tropical desatendida causada por hongos del género Paracoccidioides. Son diversos los síntomas relacionados con esta enfermedad; sin embargo, los pulmones y la piel suelen estar afectados en mayor medida. La enfermedad se observa principalmente en personas que viven en zonas rurales de América Latina.

Caso clínicoPresentamos un caso de paracoccidioidomicosis diseminada grave en un niño que respondió lentamente al tratamiento antifúngico. En tres meses la presentación clínica progresó hasta la aparición de hepatoesplenomegalia, necrosis de ganglios linfáticos cervicales y abdominales, y formación de absceso esplénico. La respuesta clínica a la anfotericina B desoxicolato y al itraconazol fue lenta, lo que resultó en la aparición de derrames pleurales y de la cavidad peritoneal, insuficiencia cardíaca y shock. La anfotericina B desoxicolato fue reemplazada por la forma liposomal del mismo antifúngico, sin observarse respuesta clínica. Posteriormente se añadió prednisona al tratamiento, lo que llevó a la mejora del paciente. Los títulos serológicos de anticuerpos frente a Paracoccidioides fueron atípicos, con títulos muy bajos en la fase crítica y elevación significativa durante la fase de convalecencia. La infección se resolvió con anfotericina B desoxicolato, anfotericina B liposomal y el uso de corticosteroides. La serología de paracoccidioidomicosis fue no reactiva dos años después del alta.

ConclusionesDebido a la intensa respuesta inflamatoria desencadenada por las células de Paracoccidioides, la administración de prednisona en dosis bajas en cortos periodos de tiempo pudo modular la respuesta inflamatoria y ayudó en la respuesta al tratamiento antifúngico.

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a deep, systemic mycosis endemic in Latin America, with the highest prevalence reported in Brazil. This neglected tropical disease is caused by members of the Paracoccidioides brasiliensis species complex (lineages S1, PS2, PS3 and PS4) and Paracoccidioides lutzii.10,12,17,18 The predominant clinical form in children, adolescents and young adults is acute/subacute (5–25% of the cases).16 In children and adolescents the incidence of paracoccidioidomycosis is 5–10%, and the main general manifestations are fever, malaise, and malnutrition. Organ involvement is mainly related to fungal burden, in 90% of the cases lymphadenomegaly has been observed, and less frequently hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites, and/or skin lesions. Central nervous system involvement has rarely been reported in children and adolescents, this form being usually seen in adult patients.16 Laboratory diagnosis is performed through direct examination and culture of biological samples, often being lymph node aspirate and tissue biopsies.17 Double immunodiffusion test is one of the tools used to assist in clinical and laboratory diagnosis, and it is mainly used for the follow-up of patients in order to monitor the course of the disease.13 The commonly used therapy to treat pediatric paracoccidioidomycosis is co-trimoxazole, a combination of sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, due to its efficacy and easy administration.13 We herein describe the case of an immunocompetent child with disseminated, juvenile paracoccidioidomycosis with slow response to antifungal treatment and improvement after the introduction of prednisone to the treatment.

A 9-year-old male child from the rural area of Carlinda, in the north of the state of Mato Grosso-Brazil, presented with a 3-month history of daily fever, accompanied by low back pain and prostration. Two months earlier, he had presented with a cervical tumor and an increased abdominal volume, anemia, significant weight loss and a pulmonary condition diagnosed as pneumonia. Physical examination showed fever, severe malnutrition, pallor of the mucous membrane, bilateral cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes measuring approximately 2–4cm in diameter, abdominal distension with hepatomegaly (8cm from the right costal margin), and splenomegaly (6cm from the left costal margin).

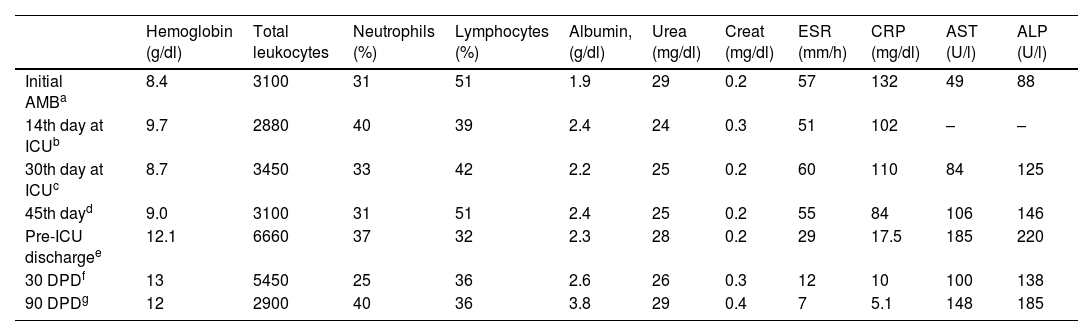

Laboratory tests showed moderate anemia (hemoglobin: 8.4g/dL; MCV 72.2fl; RDW 17.8%); erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 57mm; leukopenia (3100leukocytes/mm3; lymphocytes 51%, neutrophils 31%); platelets 195,000/mm3; C-reactive protein (CRP): 132mg/L, albumin: 1.9g/dL (Table 1). Serology for toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis A, B and C were all negative. Bone marrow biopsy showed no neoplastic infiltration or infection. Cervical lymph node biopsy showed chronic, granulomatous lymphadenitis, with the formation of multinucleated giant cells and the presence of large number of fungal structures resembling Paracoccidioides species.

Evolution of laboratory results from the start of antifungal treatment until three months after hospital discharge.

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | Total leukocytes | Neutrophils (%) | Lymphocytes (%) | Albumin, (g/dl) | Urea (mg/dl) | Creat (mg/dl) | ESR (mm/h) | CRP (mg/dl) | AST (U/l) | ALP (U/l) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial AMBa | 8.4 | 3100 | 31 | 51 | 1.9 | 29 | 0.2 | 57 | 132 | 49 | 88 |

| 14th day at ICUb | 9.7 | 2880 | 40 | 39 | 2.4 | 24 | 0.3 | 51 | 102 | – | – |

| 30th day at ICUc | 8.7 | 3450 | 33 | 42 | 2.2 | 25 | 0.2 | 60 | 110 | 84 | 125 |

| 45th dayd | 9.0 | 3100 | 31 | 51 | 2.4 | 25 | 0.2 | 55 | 84 | 106 | 146 |

| Pre-ICU dischargee | 12.1 | 6660 | 37 | 32 | 2.3 | 28 | 0.2 | 29 | 17.5 | 185 | 220 |

| 30 DPDf | 13 | 5450 | 25 | 36 | 2.6 | 26 | 0.3 | 12 | 10 | 100 | 138 |

| 90 DPDg | 12 | 2900 | 40 | 36 | 3.8 | 29 | 0.4 | 7 | 5.1 | 148 | 185 |

ALP: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; AMB: amphotericin B; ICU: intensive care unit; DPD: days post-discharge; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP; C-reactive protein.

The patient developed massive ascites, bilateral pleural effusion and acute respiratory distress, and was transferred to the intensive care unit where he stayed for 36 days due to alternating periods of clinical improvement and worsening. He required bilateral chest drainage, six paracentesis, infusions of blood components and electrolyte adjustments. The patient developed heart failure that was treated with a vasoactive drug (dobutamine, 5μg/kg/min for 2 days). On the first day of admission to the ICU, and while using broad-spectrum antibiotics to prevent bloodstream infection and hospital-acquired pneumonia (ciprofloxacin, 30mg/kg/day for 8 days; vancomycin 60mg/kg/day for 14 days; meropenem 120mg/kg/day for 14 days), amphotericin B deoxycholate (1mg/kg/day) was administered. As after thirteen days neither hepatosplenomegaly, nor patient's general condition, improved, and the laboratory parameters did not change either, itraconazole was added (4.5mg/kg/day) to the antifungal therapy. Antifungal combination therapy was followed for 28 days, but the clinical picture remained severe and unstable. Amphotericin B deoxycholate was replaced by the liposomal form for 12 days, and itraconazole was maintained. The patient's transaminases concentration in serum upon admission to the ICU were 40U/L for AST and 88U/L for ALP. Seventeen days after the introduction of itraconazole, serum concentrations were 84 and 125U/L for AST and ALP, respectively, which turned to 106 and 146U/L (AST and ALP, respectively) after 30 days. The evolution of transaminases concentration during treatment and after discharge are listed in Table 1.

On the 24th day of treatment, prednisone (0.5mg/kg) was introduced and maintained for 14 days. After the introduction of the corticosteroid, there was a progressive clinical improvement, also reflected in laboratory analyses, with a decrease in erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP values, an improvement in the general condition, a reduction in ascites, visceromegaly and adenomegaly, and weight gain (Table 1).

The patient was discharged from the ICU 36 days post-hospitalization, having received amphotericin B for 36 days and itraconazole for 26 days. He was transferred to the pediatric ward, malnourished, pale +/4+, jaundiced +/4+, with abdominal distention and hepatosplenomegaly. Antifungal treatment, consisting of liposomal amphotericin B and itraconazole, was continued, and the nutritional intake increased. On the fifth day of admission to the pediatric ward, liposomal amphotericin B was replaced by sulfamethoxazole+trimethoprim (400/80mg, b.d.d.), maintaining itraconazole (4.5mg/kg/day), resulting in gradual improvement. Abdominal ultrasound after ICU discharge showed heterogeneous periaortic, pericaval and peripancreatic nodes up to 4cm in diameter, with a hyperechoic center suggestive of necrosis; imaging also showed a suggestive 2cm large splenic abscess, as well as cortical enlargement in the kidneys. After 17 days at the pediatric ward, the patient was discharged; itraconazole and sulfamethoxazole+trimethoprim in the aforementioned doses were maintained, as well as food supplementation. A weekly outpatient follow-up was scheduled. On the fourth day after discharge the patient was readmitted due to weakness and edema of the lower limbs, being hospitalized for another seven days and receiving the same medication and food supplementation. The length of stay was 64 days. The total dose of amphotericin B deoxycholate was 13mg/kg and that of liposomal amphotericin B was 73mg/kg.

Thirty days after hospital discharge the patient had gained only one kilo of weight. On physical examination, he still had cervical adenomegaly (approximately 0.5–1cm in diameter), mild cutaneous-mucosal pallor, and slightly globular and painless abdomen, without visceromegaly. Ninety days after discharge he was on regular medication and had gained two kilos of weight, spleen and liver were impalpable and the cervical nodes were smaller than 0.5cm in diameter. Laboratory results showed that transaminases were at threshold levels, attributed to drug-induced hepatitis and to the paradoxical effect of inflammation, but treatment was maintained with monthly monitoring.

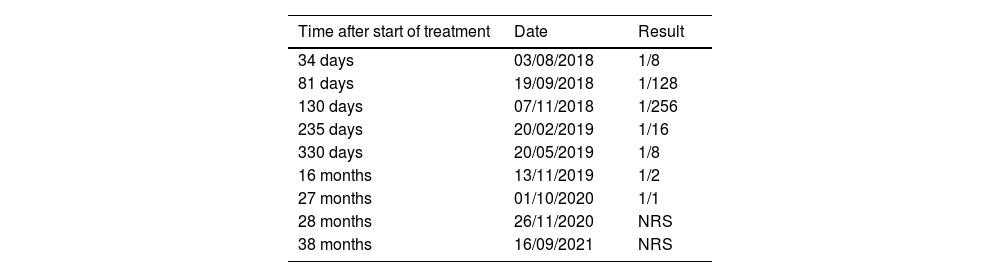

Paracoccidioidomycosis serology using the double immunodiffusion technique with the reference antigen B339 of P. brasiliensis, performed on the 34th day of treatment, showed a titer of 1/8, with a progressive increase until the 80th day of treatment (1/256), and a progressive decrease until the test became non-reactive two years post-discharge (Table 2).

Evolution of serology titers with Ag B339 (P. brasiliensis) after the start of specific treatment.

| Time after start of treatment | Date | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 34 days | 03/08/2018 | 1/8 |

| 81 days | 19/09/2018 | 1/128 |

| 130 days | 07/11/2018 | 1/256 |

| 235 days | 20/02/2019 | 1/16 |

| 330 days | 20/05/2019 | 1/8 |

| 16 months | 13/11/2019 | 1/2 |

| 27 months | 01/10/2020 | 1/1 |

| 28 months | 26/11/2020 | NRS |

| 38 months | 16/09/2021 | NRS |

NRS: non-reactive serum.

The acute/subacute form of paracoccidioidomycosis, also known as the juvenile form, mainly affects children, adolescents and young adults. This clinical presentation is usually widespread, moderate to severe, with a similar distribution by sex, especially in children.10,14,17 Any organ or system can be affected. The majority of the case series in the literature reported adenomegaly, abdominal distention, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, osteoarticular lesions and intra-abdominal masses as the predominant findings, in addition to constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and emaciation.5,7,10 Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to both take control of the disease and support a favorable outcome. For this reason, it is necessary that pediatricians and clinicians have a high index of suspicion, knowing the local epidemiology and the characteristics of the disease; in the acute juvenile form the clinical findings are nonspecific, and differential diagnoses with lymphoproliferative diseases, lymph node and disseminated tuberculosis, visceral leishmaniasis, histoplasmosis, infectious mononucleosis, among others, should be considered.10,14

The case presented here is an acute, severe, disseminated form of the disease with involvement of several organs, severe consumption, and complications with lethal potential. Few cases of paracoccidiodomycosis that report the presence of pleural effusion or ascites are published, being generally described as not extensive and without compromising patient's life1,3–5,7,8,11; nevertheless, ascites has been reported as an indicator of poor prognosis in acute/subacute paracoccidioidomycosis.15 Cardiac involvement characterized by cardiomegaly, pericarditis and pericardial effusion is uncommon and has been associated with severe disease.6,7

The poor clinical response to antifungal treatment with amphotericin B deoxycholate and itraconazole is noteworthy, as the large hepatosplenomegaly, the abdominal adenomegaly and the ascites persisted after three weeks of treatment, in addition to the delay in food intake regain. After the addition of low-dose prednisone, on day 24th of the antifungal treatment, the patient showed progressive clinical improvement, being discharged from the ICU 12 days later. Few cases of paracoccidioidomycosis treated with antifungals and steroids as adjunctive therapy have been described, all of them with severe paracoccidioidomycosis and little response to antifungals; clinical improvement was shown after starting adjunctive steroid therapy.2,8,9

The pathophysiology of paracoccidioidomycosis involves an intense inflammatory response against the antigens of Paracoccidioides species, which may start during antifungal treatment by the release of more antigens from the lysed fungal cells, sometimes inducing an increased immune response evidenced by the rise in antibody titers. However, this increased immune response can have a deleterious effect2 that would explain our patient's worsening condition despite receiving an adequate antifungal therapy. The addition of prednisone may have acted as a modulator of the inflammatory and immune responses, leading to patient's recovery and increased titers in immunodiffusion tests. This effect is similar to the paradoxical reaction present in the inflammatory syndrome of immune reconstitution described in mycobacterial infections, such as leprosy and tuberculosis, and in the meningeal cryptococcosis, especially in patients with HIV/AIDS.19,20 In our hospital we previously had combined prednisone with amphotericin B deoxycholate treatment in two patients with similar disease severity; there was a good clinical response in both patients.

It is necessary to emphasize the importance of nutritional care in the treatment of children with paracoccidioidomycosis, as neglecting this aspect will likely result in an inevitable fatal course of the disease. The replacement of all nutrients, enteral or parenterally, should not be delayed, because even if the patient accepts some amount of food orally, which is rare, it is usually not sufficient to sustain the high needs for coping with the disease.

In conclusion, paracoccidioidomycosis in its systemic form is a serious and potentially fatal disease if left untreated or treated late and, therefore, it requires early diagnosis and prompt treatment. Due to the intense inflammatory response triggered by Paracoccidioides cells, the use of prednisone in low doses for a short period may regulate this inflammatory response and further be of help with the antifungal treatment.

EthicsThis study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Júlio Muller Hospital under number 3.285.959/2019, CAAE: 2 08640919.8.0000.5541.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.