The study of floral phenology patterns and floral visitors of palms is key to understanding evolutionary interactions between plants and insects. We studied the flowering pattern and floral visitors of Wettinia kalbreyeri in an Andean montane forest of Colombia. We monitored 100 adult palms throughout 1-year and observed an asynchronous flowering pattern at the population level. Collectively, those 100 individuals developed 125 inflorescences, composed of 96 staminates, 28 pistillates, and 1 androgynous. We classified 39 morphotypes of insect floral visitors, including beetles, bees, and flies. The composition and abundance of floral visitors between staminate and pistillate inflorescences were markedly different. Sap beetles – Mystrops – were the most abundant visitors in both pistillate and staminate inflorescences. We suggest that the higher production of staminate inflorescences compared to pistillate inflorescences and the availability of inflorescences throughout the year may promote a permanent and abundant community of floral visitors. This study suggests that Mystrops are associated with Wettinia species in high altitude forests, as it also occurs in Ceroxylum species.

Para entender las interacciones evolutivas entre palmas e insectos, es importante estudiar los patrones de floración y los visitantes florales. Se estudiaron la floración y los visitantes florales de Wettinia kalbreyeri en un bosque de los Andes colombianos. Se monitorearon 100 palmas adultas durante un año y se observó un patrón de floración asincrónico a nivel poblacional. Colectivamente, las 100 palmas evaluadas desarrollaron 125 inflorescencias, compuestas por 96 estaminadas, 28 pistiladas y una andrógina. En total, clasificamos 39 morfoespecies de insectos, incluyendo escarabajos, abejas y moscas. La composición y abundancia de los visitantes florales fue marcadamente diferente entre las inflorescencias estaminadas y pistiladas. Mystrops fue más abundante en ambas inflorescencias. Sugerimos que la alta producción de inflorescencias estaminadas, en comparación con inflorescencias pistiladas, y la disponibilidad de inflorescencias durante todo el año, favorece la permanencia de visitantes florales. Este estudio sugiere que Mystrops está relacionado con especies de Wettinia en bosques altoandinos, como ocurre en el género Ceroxylum.

The palm family, Arecaceae, encompasses a wide diversity of flowering patterns and floral visitors. Flowering patterns range from asynchrony to tight synchrony (Bernal & Ervik, 1996; Borchsenius, 1993; Cifuentes, Moreno, & Arango, 2010; Martén & Quesada, 2001; Rojas & Stiles, 2009), while floral visitors include, but are not limited to, beetles, bees, and flies (Barfod, Hagen, & Borchsenius, 2011; Henderson, 1986). Theoretically, the 2 components (flowering patterns and floral visitors) interact to maximize reproductive success (Martén & Quesada, 2001; Núñez, Bernal, & Knudsen, 2005). This interaction, consequently, creates a very special opportunity to study how evolutionary patterns (e.g., coevolution and specialization) work in natural populations (Núñez et al., 2005).

Until now, flowering patterns and floral visitors have only been described for approximately 5% of all extant palm species (Barfod et al., 2011). Furthermore, most of these studies were carried out in lowland forests (below 1,000m elevation), with very little research conducted in high-altitude forests (above 2,000m elevation). Studies on palm species in high-altitude forests are, therefore, needed to conduct comparative analyses. For instance, comparing palm species of the same genus in high-altitude forests versus lowland forests would elucidate whether the diversity of floral visitors remains constant or varies along an altitudinal gradient.

Wettinia is a palm genus that remains little studied. It comprises 21 species, which are widely distributed in both latitude (from Bolivia to Panama) and altitude (from 0 to 3,500m), but 1 species – W. quinaria (O. F. Cook & Doyle) – has been previously studied (see Núñez et al., 2005). Within Wettinia species, Wettinia kalbreyeri (Burret) R. Bernal occurs throughout the Andean montane forests from Colombia to Ecuador, ranging from 1,800 to 2,800m in elevation (Bernal, 1995). W. kalbreyeri is entirely unknown scientifically and faces a dramatic selective exploitation where its stems are used for construction (Bernal, 2013; Lara, Díez, & Moreno, 2012).

We studied both flowering pattern and floral visitors of W. kalbreyeri in an Andean montane forest of Colombia, and compared our findings with previously published results of W. quinaria (Núñez et al., 2005). We predict that W. kalbreyeri exhibits an asynchronous flowering pattern similar to W. quinaria due to their recent common ancestry. We also evaluated whether W. kalbreyeri has a high diversity of floral visitors, given that the insect diversity associated with palms theoretically decreases with altitude (Borchsenius, 1993). Our study is the first to describe the flowering pattern and floral visitors of W. kalbreyeri, providing rare insights into palm-insect relationships.

Materials and methodsWe conducted fieldwork at “Cuchilla Jardín-Támesis” Natural Regional Reserve (∼32,000ha), in Antioquia, Colombia. The reserve is located in the north of the Western Cordillera of the Colombian Andes (5°37′45″–5°39′18″N, 75°47′53″–75°46′30″W), ranging from 2,200 to 2,800masl. Mean annual rainfall is 3,000mm, with monthly rainfall always exceeding 100mm. Mean annual temperature is 17°C (Corantioquia, 2007). The predominant life zone in the reserve is Tropical Lower Montane Moist Forest (sensuHoldridge, 1978). Forests are dominated by W. kalbreyeri (Lara et al., 2012), although other species occur, such as Billia rosea (Planch. & Linden), Ulloa & P. Jørg. (Hippocastanaceae), Chrysochlamys colombiana (Cuatrec.) Cuatrec. (Clusiaceae), Dicksonia sellowiana Hook. (Dicksoniaceae), Hieronyma antioquensis Cuatrec. (Phyllanthaceae), Ladenbergia macrocarpa (Vahl) Klotzsch, (Rubiaceae), Palicourea andaluciana Standl. (Rubiaceae), and Prestoea acuminata (Willd.) H. E. Moore (Arecaceae).

Study speciesW. kalbreyeri (Burret) is a monoecious palm that develops both staminate and pistillate inflorescences, but an individual does not unfold both inflorescences simultaneously, hence its reproductive system is obligatory xenogamy. Macana palms have up to 15 inflorescences per node, each containing between 7 and 20 pendulous branches. Fruits are slightly ellipsoidal and 3.5cm in length; seeds are ovoid to ellipsoidal and 2cm in length. This palm has a solitary stem (maximum height of 20m) supported by a cone of stilt roots about 1m in height with 1cm-length spines. Leaves are polystic, with up to 5 leaves per palm (Galeano & Bernal, 2010).

Population phenologyWe monitored, fortnightly, 100 marked adult palms between January and December 2010. We chose these palms randomly along a 3km track at ca. 2,650m. We classified our observations as staminate inflorescence and pistillate inflorescences. We calculated the relative frequency of those 2 phenophases following Bencke and Morellato (2002): (a) no synchrony (less than 20% of individuals were in the same phase), (b) low synchrony (between 20% and 60% of individuals), and (c) high-synchrony (more than 60% of individuals).

Floral visitorsWe collected 12 inflorescences (6 staminate and 6 pistillate) of W. kalbreyeri to characterize its floral visitors. We carried out 3 field trips in March, July and September 2010. In each field trip, we collected 2 staminate inflorescences and 2 pistillate inflorescences. To collect the inflorescences, we climbed the palm stem to reach the inflorescence (ca. 15m). On top of the palm, we cut and preserved the inflorescence in a bag with ethanol at 70%. Further analyses were carried out in a laboratory between 3 days of collection. We manually separated, counted, and classified at a morphotype level all insects in the 12 inflorescences. Floral visitors were categorized following Núñez and Rojas (2008) as: (a) highly abundant (more than 1,000 individuals), (b) abundant (between 100 and 500 individuals), (c) rare (between 10 and 100 individuals), and (d) sporadic (between 1 and 10 individuals).

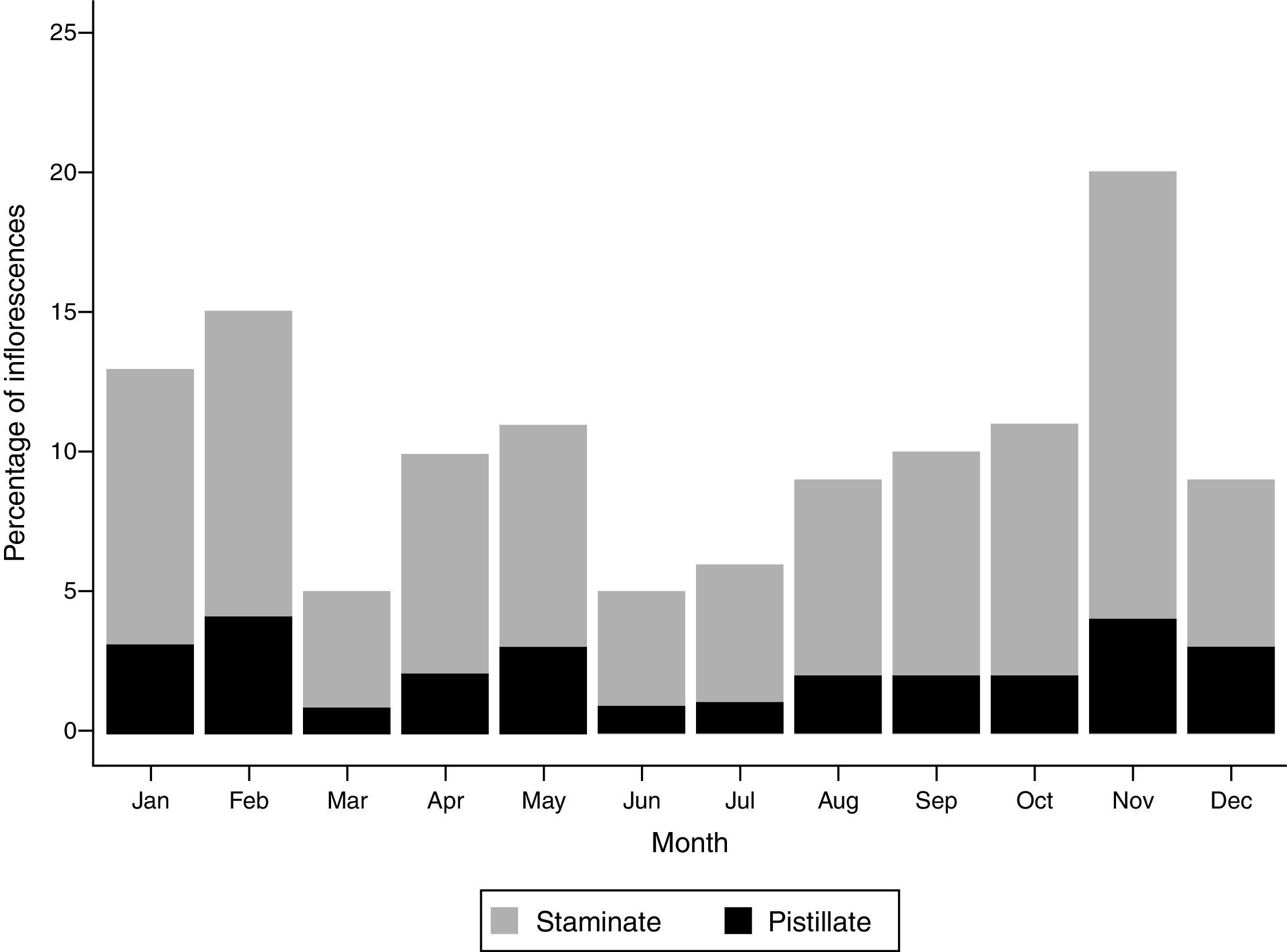

ResultsPopulation phenologyWe observed both staminate and pistillate inflorescences (Fig. 1) throughout the year (Fig. 2). However, there was a higher proportion of staminate inflorescences (mean=12.4%, sd=3.1%, n=100) than pistillate ones (mean=3.4%, sd=2.5%, n=100). Pistillate inflorescences were not common (always under 10%) and exhibited little variation throughout the year (Fig. 2). Monthly, we found from 3 to 4 staminate inflorescences for each pistillate inflorescence. Collectively, those 100 individuals developed 96 staminate inflorescences, 28 pistillate inflorescences and 1 androgynous inflorescence. Importantly, the flowering pattern (accounting for both staminate and pistillate inflorescences) did not correlate with precipitation (Spearman test, rs=−0.09, p=0.77), yet different environmental variables, such as solar radiation, relative humidity, and cloudiness, may influence the flowering pattern observed.

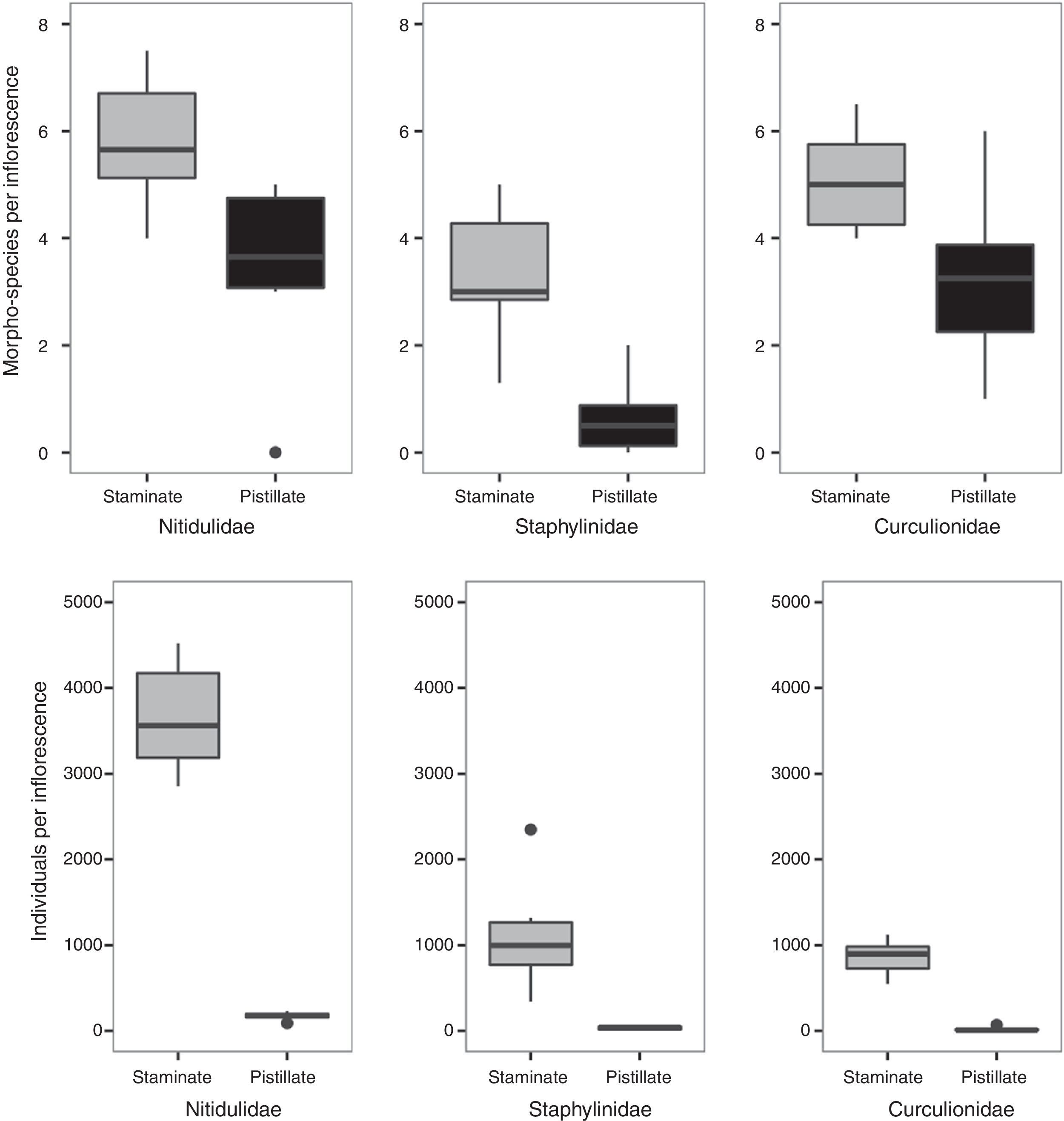

We classified 39 morphotypes of insects associated with the inflorescences of W. kalbreyeri. Of these, 32 morphotypes were observed in the staminate inflorescences, and 27 in the pistillate inflorescences (see Appendix and main floral visitors in Fig. 3). We found (on average) 5,480 individuals in each staminate inflorescence, whereas we found 232 individuals in each pistillate inflorescence. The floral visitor community was characterized by a few dominant species and many rare species (Appendix). The order Coleoptera was the most abundant and diverse (Fig. 4). Within Coleoptera, the highest number of morphotypes and the highest abundance was found in the family Nitidulidae, followed by Staphylinidae and Curculiodinae (Fig. 4). Four species of Mystrops (Nitidulidae) and 3 morphotypes of the subfamily Aleochariane represented 62% and 18% of the total abundance of insects in the staminate inflorescences, respectively. Similarly, 3 Mystrops species and 2 morphotypes of the Aleocharinae represented 72% and 15%, of the total abundance of insects in the pistillate inflorescences respectively. The family Curculionidae was well-represented (12 morphotypes), but its abundance only reached 18% in the staminate inflorescences and only 1% in the pistillate inflorescences (Fig. 4).

Major floral visitors of Wettinia kalbreyeri in an Andean montane forest of Colombia. Mystrops sp. 1 (a), Mystrops sp. 2 (b), Mystrops sp. 3 (c), Mystrops sp. 4 (d), Mystrops sp. 6 (e), Mystrops sp. 7 (f), Mystrops sp. 8 (g), Curculionidae Gen 1. sp. 1 (h), Phyllotrox sp. 1 (i), Phyllotrox sp. 2 (j), Andranthobius sp. 1 (k), Metamasius sp. 1 (l), Curculionidae Gen 5. sp. 2 (m), Phalacrididae Gen. 1sp. 1 (n), Tingitidae Gen.1 sp. 1 (o), Nitidulidae Gen. 1 sp. 1 (p), Staphylinidae-Aleocharinae Gen. 1 sp. 1 (q), Staphylinidae-Aleocharinae Gen. 2 sp. 1 (r), Staphylinidae-Aleocharinae Gen. 3 sp. 1 (s), Drosophila sp. 1 (t), and Hymenoptera gen. 1 sp. 1 (u).

According to our prediction, we observed an asynchronous flowering pattern (sensuBencke & Morellato, 2002) over the 12-month time period. Such a pattern has been reported in W. quinaria (Núñez et al., 2005). Flowering asynchronously is typical in many palm species (Bernal & Ervik, 1996; Martén & Quesada, 2001). For instance, Aiphanes chiribogensis Borchsenius & Balslev, an endemic palm of Ecuador whose distribution ranges from 1,700m to 2,100masl, also exhibits an asynchronous flowering pattern (Borchsenius, 1993). Flowering asynchronously has been suggested as a mechanism to promote the presence of floral visitors (Bernal & Ervik, 1996; Núñez et al., 2005), the vectors of pollination. Thus, the seemingly asynchronous flowering pattern exhibited by W. kalbreyeri may help to maintain a diverse community of floral visitors.

Overall, W. kalbreyeri produced fewer inflorescences (100 individuals produced 125 inflorescences) than W. quinaria (73 individuals produced 308 inflorescences). However, despite their contrasting ecological environments, W. kalbreyeri and W. quinaria produced similar proportions of staminate and pistillate inflorescences. This finding potentially contributes to the observed maintenance of floral visitors throughout the year in both species.

Beetles, bees and flies are the principal floral visitors of W. kalbreyeri. These 3 groups of insects have been previously found in many palm species (Barfod et al., 2011; Henderson, 1986). Contrary to our prediction of fewer floral visitors at high-altitude, we found a similar number of insect morphotypes in W. kalbreyeri compared to W. quinaria, which occurs at a lower altitude (see Núñez et al., 2005). We also found a similar number of insect genera and families between W. kalbreyeri and W. quinaria. This contradicts our expectation because a decrease in the number of floral visitors across an altitudinal gradient has been previously reported in palms (genus Aiphanes, Borchsenius, 1993). Unfortunately, current taxonomic limitations in the classification at the species level of floral visitors restrict detailed comparisons across palm species. Notably, W. kalbreyeri is mainly visited by beetles; however, it has been suggested that beetles have a limited role above 1,000m elevation (Borchsenius, 1993). This apparent contradiction also deserves further research.

The markedly higher abundance of the sap beetles Mystrops in W. kalbreyeri suggests that these beetles are the main pollinators of W. kalbreyeri. Likewise, Mystrops beetles were reported as the main pollinators of W. quinaria (Núñez et al., 2005). Because we did not evaluate pollen transfer, visitors from other families such as Staphylinidae and Aleocharinae may also play a role as pollinators.

The tight association between Wettinias and Mystrops has also been observed in palm species of the genus Ceroxylum (see details: Kirejtshuk & Couturier, 2009, 2010). This close relationship between sap beetles and palms (Connell, 1974; Henderson, 1986; Núñez et al., 2005) may also occur in unstudied species distributed in high-altitude forests.

We have 2 major conclusions of this study: (1) we suggest that the higher production of staminate inflorescences and the availability of those inflorescences throughout the year may promote a permanent and abundant community of floral visitors, potentially mediating the reproductive success of W. kalbreyeri; (2) we found a high diversity of floral visitors (morphotypes) associated with W. kalbreyeri in a high-altitude Andean forest, despite theoretical evidence and empirical observations in a palm genus gradient that insect diversity decreases with altitude (Borchsenius, 1993). Such diversity, and the specific associations of sap beetles previously reported (Wettinia: Núñez et al., 2005; Ceroxylum: Kirejtshuk & Couturier, 2009, 2010) deserve to be investigated under a meta-analytic approach. Future research, particularly on W. kalbreyeri, should seek to confirm the identity of the main pollinators and the floral visitors’ behavior, which may provide insight into the evolution of the flowering pattern in W. kalbreyeri.

We thank Juan. L. Toro, Juan. C. Carvajal, Germán Buitrago, and Sandra Suárez for assistance in the field. We also thank 2 anonymous reviewers and the editor-in-charge (Neptalí Ramírez-Marcial) for suggestions that improved the manuscript. The Universidad Nacional de Colombia supported this project (Research grant N. 20101007362).

| Order/family/morphotype | Staminate phase (n=6) | Pistillate phase (n=6) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PD | AA (SD) | AC | PD | PA (SD) | AC | |

| Coleoptera | ||||||

| Curculionidae | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 1.0 | 83.2 (80.8) | ** | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.4) | + |

| Gen 1. sp. 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − | 0.2 | 0.7 (0.6) | + |

| Gen 2. sp. 1 | 0.2 | 0.3 (0.8) | + | 0.3 | 1.5 (3.2) | + |

| Gen 3. sp. 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 (0.8) | + | 0.3 | 2.7 (5.2) | + |

| Gen 4. sp. 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.4) | + |

| Phyllotrox sp. 1 | 1.0 | 525.3 (528.2) | *** | 0.2 | 2.3 (5.7) | + |

| Phyllotrox sp. 2 | 0.7 | 6.8 (8.9) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Gen 5. sp. 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − | 0.3 | 1.2 (2.0) | + |

| Gen 5. sp. 2 | 0.3 | 0.3 (0.5) | + | 0.7 | 2.8 (3.3) | + |

| Andranthobiussp. 1 | 1.0 | 230.3 (252.0) | ** | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Metamasiussp. 1 | 0.3 | 9.3 (18.4) | + | 0.5 | 6.3 | + |

| Phalacrididae | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 0.2 | 0.3 (0.8) | + | 0.5 | 1.3 | + |

| Nitidulidae | ||||||

| Mystrops sp. 1 | 1.0 | 2573.3 (1616.5) | *** | 0.5 | 0.7 | + |

| Mystrops sp. 2 | 1.0 | 504.5 (355.4) | *** | 0.5 | 111.2 (244.5) | ** |

| Mystrops sp. 3 | 1.0 | 231.0 (172.7) | ** | 0.5 | 3.8 (7.5) | + |

| Mystrops sp. 4 | 1.0 | 342.3 (262.9) | ** | 0.5 | 52.2 (123.9) | * |

| Mystrops sp. 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − | 0.2 | 0.8 (2.0) | + |

| Mystrops sp. 6 | 0.3 | 0.3 (0.5) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Mystrops sp. 7 | 0.3 | 0.3 (0.5) | + | 0.3 | 1.2 (2.4) | + |

| Mystrops sp. 8 | 0.5 | 1.3 (2.0) | + | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.4) | + |

| Mystrops sp. 9 | 0.2 | 0.3 (0.8) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Mystrops sp. 10 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − | 0.2 | 0.3 (0.8) | + |

| Mystrops sp. 11 | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.4) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Gen. 1 sp. 1 | 0.3 | 0.3 (0.5) | + | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.4) | + |

| Staphylinidae | ||||||

| Aleocharinae | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 1.0 | 332.7 (161.7) | ** | 0.3 | 12.5 (30.1) | * |

| Gen 2. sp. 1 | 1.0 | 617.0 (575.8) | *** | 0.3 | 22.2 (36.5) | * |

| Gen 3. sp. 1 | 0.7 | 118.7 (275.2) | ** | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Gen 4. sp. 1 | 0.3 | 47.7 (116.3) | * | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Gen 5. sp. 1 | 0.2 | 4.7 (11.4) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Gen 6. sp. 1 | 0.2 | 0.7 (1.6) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Coccinelidae | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 0.5 | 1.5 (2.0) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Chrysomelidae | ||||||

| Longitarsussp. 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 (0.8) | + | 0.2 | 1.3 (3.3) | + |

| Melolontidae | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.4) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

| Hymenoptera | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 0.8 | 13.0 (14.9) | * | 0.5 | 1.2 (1.3) | + |

| Diptera | ||||||

| Drosophilidae | ||||||

| Drosophila sp. 1 | 1.0 | 196.2 (116.7) | ** | 0.5 | 1.3 (2.0) | + |

| Hemiptera | ||||||

| Antrocoridae | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 1.0 | 13.2 (2.9) | * | 0.7 | 3.7 (5.8) | + |

| Tingitidae | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − | 0.3 | 0.5 (0.8) | + |

| Homoptera | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | − | 0.2 | 0.2 (0.4) | + |

| Dermaptera | ||||||

| Gen 1. sp. 1 | 0.2 | 0.3 (0.8) | + | 0.0 | 0.0 | − |

Peer Review under the responsibility of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.