Childhood trauma has been reported as a risk factor for psychosis. Different types of traumatic experiences in childhood could lead to different clinical manifestations in psychotic disorders.

MethodsWe studied differences in social cognition (emotion recognition and theory of mind) and clinical symptoms in a sample of 62 patients with psychosis (less than five years of illness) and childhood trauma, analysing performance by trauma type.

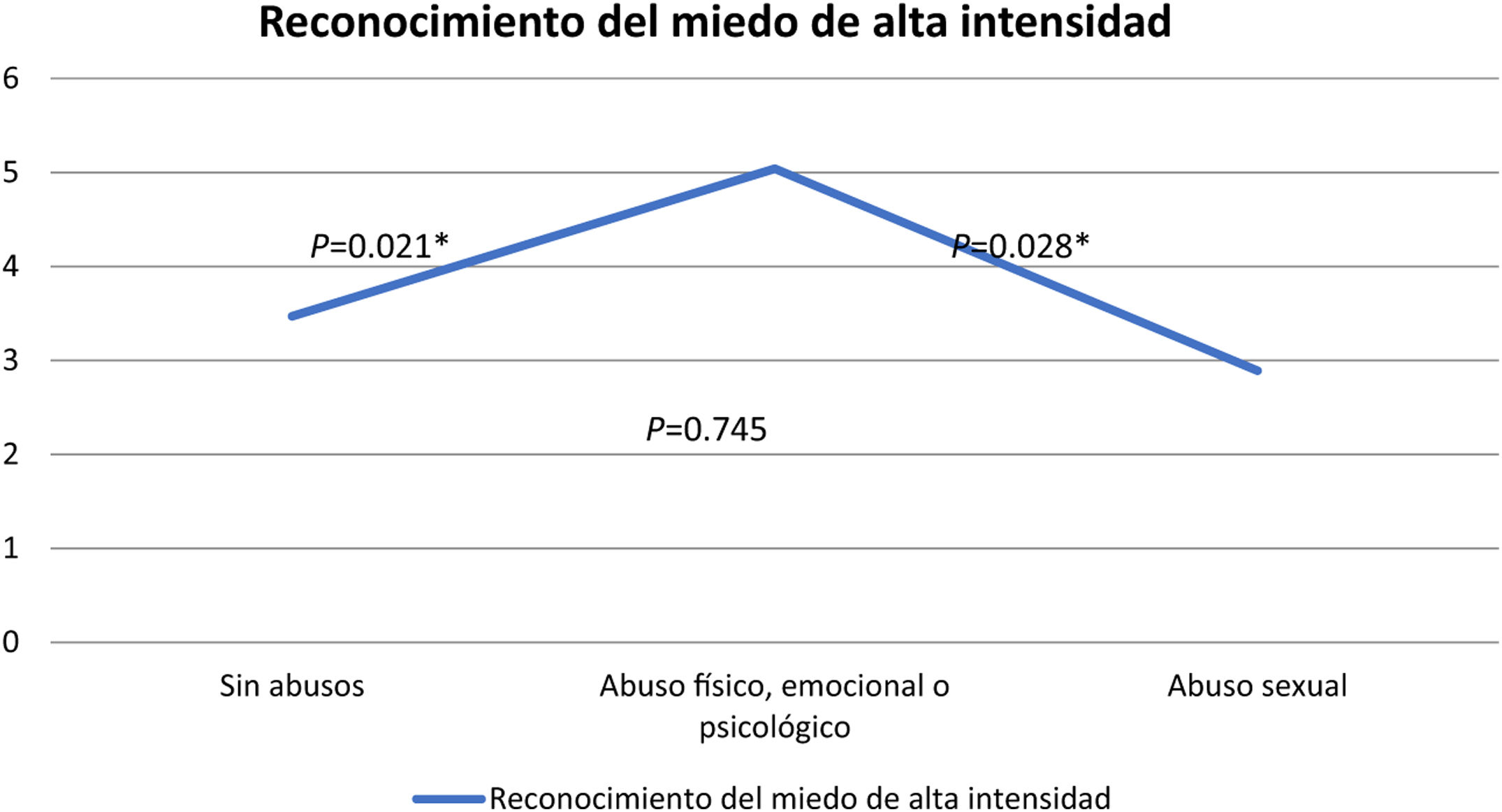

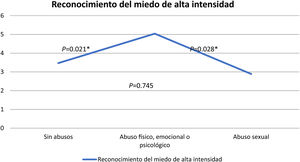

ResultsPsychotic patients with a history of childhood trauma other than sexual abuse were more capable of recognizing fear as a facial emotion (especially when facial stimuli were non-degraded) than participants with a history of sexual abuse or with no history of childhood trauma (P = .008). We also found that the group that had suffered sexual abuse did not show improvement in fear recognition when exposed to clearer stimuli, although this intergroup difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .064). We have not found other differences between abuse groups, neither in clinical symptoms (PANSS factors) nor in Hinting Task scores.

ConclusionWe have found differences in fear recognition among patients with psychotic disorders who have experienced different types of childhood trauma.

El trauma infantil ha sido descrito como un factor de riesgo para la psicosis. Diferentes tipos de experiencias traumáticas en la infancia podrían conducir a diferentes manifestaciones clínicas en los trastornos psicóticos.

Material y métodosEstudiamos las diferencias en la cognición social (reconocimiento de emociones y teoría de la mente) y los síntomas clínicos en una muestra de 62 pacientes con psicosis (menos de cinco años de enfermedad) y trauma infantil, analizando los resultados en cada tarea según el tipo de trauma.

ResultadosLos pacientes psicóticos con antecedentes de trauma infantil distinto al abuso sexual fueron más capaces de reconocer el miedo en una tarea de reconocimiento facial de emociones (especialmente cuando la imagen facial no estaba degradada) que los participantes con antecedentes de abuso sexual o sin antecedentes de trauma infantil (P = .008). También encontramos que el grupo que había sufrido abuso sexual no mostró mejoría en el reconocimiento del miedo cuando se lo expuso a estímulos más intensos (comparación forma degradada y no degradada), aunque esta diferencia intergrupal no alcanzó significación estadística (P = .064). No hemos encontrado otras diferencias entre los grupos de abuso, ni en los síntomas clínicos (factores PANSS) ni en las puntuaciones de Hinting Task.

ConclusiónHemos encontrado diferencias en el reconocimiento del miedo entre pacientes con trastornos psicóticos que han experimentado diferentes tipos de trauma infantil.

Social cognition is the ability to process and apply social information.1 Social cognition is commonly divided into five domains: emotional processing (with consisting of four components, ie, identifying emotions, facilitating emotions, understanding emotions, and managing emotions2), social perception, social knowledge, theory of mind, and attributional biases.3,4 Previous studies in individuals with schizophrenia have described theory of mind impairment5,6 and emotion-perception deficits1 in these patients. Additionally, individuals with psychotic disorders have greater difficulty recognizing negative emotions7 when completing emotion-perception tasks.

Performance on social cognition tasks has been proposed as a powerful predictor of functional outcome in psychosis.8,9 Previous studies have described sex differences in psychotic disorders10 as well as differences in social cognition and emotion perception,9,11 reporting greater activation of the amygdala in females exposed to negative stimuli and increased amygdala response to positive stimuli among males.11 Poor performance on emotion-recognition tasks has been correlated with disease severity,1 negative symptoms,12 and other variables such as age.1

Childhood trauma has been reported as a risk factor for psychosis.13–15 In a previous meta-analysis, Varese et al.14 found an odds ratio (OR) of 2.78 (95% confidence interval (CI), 2.34–3.31) for childhood adversity when studying risk of psychosis. Other studies showed this association between childhood adversity and psychotic-like experiences16,17 and high-risk mental states.18 Different types of childhood traumatic events have been associated with variations in risk of psychotic disorders. In a meta-analysis,14 different ORs were described for sexual abuse (OR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.98–2.87), physical abuse (OR, 2.95; 95% CI, 2.25–3.88), emotional abuse (OR, 3.40; 95% CI, 2.06–5.62), bullying (OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.83–3.11), and neglect (OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 1.71–4.92), while no statistical association was found for parental loss (P = .154). Some previous works19–21 have described that individuals at high risk of psychosis with a history of sexual abuse, but not with other types of trauma, could be more likely to convert to first-episode psychosis.

Different types of trauma could also lead to the development of specific symptoms and other clinical features.22,23 Previous studies have found that patients with bipolar disorder and a history of emotional neglect have a decreased ability to recognise anger in others,24 while a more severe psychopathological and cognitive profile has been associated with emotional and physical neglect among individuals with psychotic disorders.25 Additionally, auditory hallucinations have been linked to childhood rape,26,27 female victims of sexual abuse with first-episode schizophrenia have been associated also with auditory hallucinations,28 and increased paranoia has been evidenced among individuals brought up in institutional care.26 Some previous studies have also described a more pronounced effect of sexual abuse on the transition to psychosis among individuals at high risk19,20 when compared to other types of trauma.

As found for other relations between childhood trauma and symptoms of psychotic disorders, we hypothesize that 1) different types of trauma can lead to differences in clinical symptoms,; 2) adverse childhood experiences can affect different tasks of social cognition (theory of mind, identifying of emotions, etc); and 3) sexual abuse may produce a different effect on social cognition than other types of trauma. Our aim in this study is to test for differences in emotion perception and in theory of mind based on the type of trauma reported in childhood, with specific focus given to the issue of whether sexual abuse leads to different effects.

MethodsProcedures and sampleParticipants were recruited from mental health services in the southern area of Granada as well as the province of Jaén (Spain). Patients were recruited from the inpatient units and were evaluated at the time of discharge. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: 1) age between 18 and 65 years; 2) previous diagnosis of functional psychosis according to DSM-IV TR psychotic codes 295-298 (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, episodes of bipolar disorder with psychotic features, major depressive disorder with psychotic features, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified29); and 3) duration of illness under 5 years. The exclusion criteria consisted of having an IQ lower than 70 as measured by TONI-2 test of nonverbal intelligence,30 previous history of head trauma with loss of consciousness for >1 h, history of major neurologic illness, and somatic disorders with neurological components.

All participants provided written informed consent to take part in the study. The research protocol was approved by the local clinical research ethical committees at both the Granada and Jaén hospitals.

InstrumentsClinical assessmentSocial and demographic data on age, sex, and educational level were recorded. The presence and intensity of psychotic symptoms were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS),31 which has been validated for use in Spanish patients.32 In our analysis we used the eight factors described by Peralta and Cuesta,33 that is, positive, negative, disorganized, excited, anxious, preoccupied, depressive, and somatization.

The degraded facial affect recognition taskThe Degraded Facial Affect Recognition Task (DFAR)34 is a measure of emotion recognition. This performance-based social cognition task measures emotional face recognition in degraded photographs. Subjects are presented with photographs of 4 actors (2 male and 2 female) with different facial expressions (ie, happy, angry, fearful, neutral). Faces expressing emotions are shown with 100% (high intensity) and 70% intensity (degraded form) to increase the difficulty of the task; on the other hand, neutral faces are presented only in high-intensity form. The task consists of 64 items, with 16 facial images shown for each emotion category (8 per intensity setting). Subjects are asked to identify the expression on each face. Our analysis took into account the total number of correct answers per facial expression as well as differences found for each emotion category according to image intensity.

The hinting taskTheory of mind was assessed with the Hinting Task. The Hinting Task tests the ability of subjects to infer the real intentions behind indirect speech. The original task is composed of 10 short stories narrating an interaction between two characters.5 All stories end with one of the characters dropping an obvious hint. The study subject is then asked what the character really meant when he or she provided this information. A correct answer at this point is assigned a score of 2. If the answer is wrong, and the subject needs another cue to give the correct answer, a score of 1 is given. Wrong answers following two attempts are given a score of 0. Original version was adapted and validated to Spanish.35 For our study we used a short version containing four stories used in previous research.36,37 Scoring was calculated as the sum of all items, with scores ranging from 0 to 8.

Childhood traumaTo assess childhood trauma we used a semi-structured interview employed in previous studies.17,38 Subjects were asked if they had experienced any kind of trauma (ie emotional neglect, psychological abuse, physical abuse, or sexual abuse) before age 16. Subjects scored the frequency of each type of trauma on a 6-point scale: 1 never; 2 once; 3 sometimes; 4 regularly; 5 often; and 6 very often. For emotional neglect, psychological abuse, and physical abuse, a subject was considered to have experienced a childhood trauma if the score indicating that particular kind of trauma was >3; conversely, and consistent with previous studies,17,38 subjects were considered not to have experienced a particular childhood trauma if the score for a given item was 3 or less. For sexual abuse, subjects were considered to have experienced trauma if the score was >1 (that is, at least once during childhood). For analysis, we divided trauma into 3 groups: no trauma, trauma of any kind other than sexual abuse, and sexual abuse; in other words, this latter group contained all subjects who had been subjected to sexual abuse any number of times and regardless of whether they had experienced any other kind of trauma.

Data analysisStatistical analysis was performed using SPSS™ (versions 21.0–23.0). First, we analysed differences in emotion recognition between groups. We used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to measure the normality of score distribution, revealing that only recognition of facial expressions of happiness did not follow a normal distribution. Differences in happiness recognition were evaluated with the Kruskal-Wallis test, and recognition of other emotions was assessed with a one-way ANOVA, testing differences within groups with a post hoc analysis (Tukey). We then studied the differences between groups for the other variables (ie sex, age, years of education, and PANSS factors) using ANOVA or the chi-squared test where appropriate. Following this, we carried out an ANCOVA multivariate analysis, taking those variables found to be significantly different between groups as covariates.

A general linear model for repeated measures was constructed to compare the longitudinal effect of improvement in emotion recognition at greater image intensity (improvement between degraded and non-degraded forms) between the different groups of abuse type. This same effect was also measured within each group with the Student t-test (non-abused group and the groups with physical or emotional abuse) and by means of non-parametric testing for the sexual abuse group.

We also used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to test for normal distribution when analysing how facial expressions of fear are misinterpreted. Scores indicating misinterpretation of fearful facial expressions, in which these were taken to be neutral expressions, follow a normal distribution; scores for fearful expressions mistaken for happy or angry faces did not follow a normal distribution. We used an ANOVA test with a post hoc analysis (Tukey) to analyse differences between abuse-type groups regarding the frequency with which fear was incorrectly interpreted as a neutral expression, and a Kruskall-Wallis test with the other scores (“fear mistaken for anger” and “fear mistaken for happiness”).

ResultsSample characteristics and abuse groupsSixty-two patients with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder were included in the analysis. We divided the sample into the three groups of abuse as described in methods section.

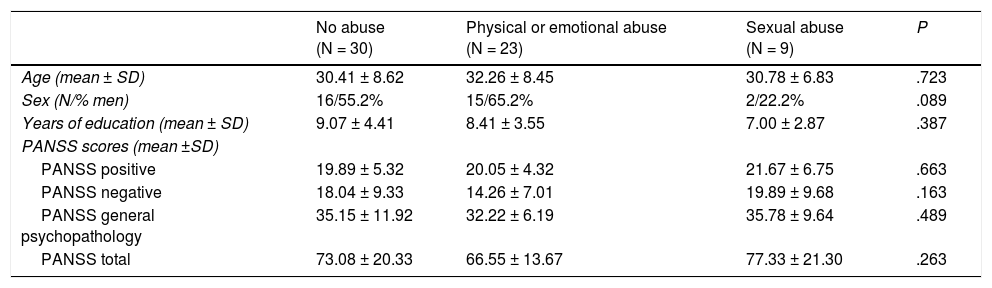

Table 1 shows differences in age, sex, years of education, and PANSS score between groups. We did not find differences in the distribution of these variables between groups (neither in the PANSS eight factors nor in classic subscales). More details are shown in the Supplementary material.

Social and demographic data and PANSS scores.

| No abuse (N = 30) | Physical or emotional abuse (N = 23) | Sexual abuse (N = 9) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 30.41 ± 8.62 | 32.26 ± 8.45 | 30.78 ± 6.83 | .723 |

| Sex (N/% men) | 16/55.2% | 15/65.2% | 2/22.2% | .089 |

| Years of education (mean ± SD) | 9.07 ± 4.41 | 8.41 ± 3.55 | 7.00 ± 2.87 | .387 |

| PANSS scores (mean ±SD) | ||||

| PANSS positive | 19.89 ± 5.32 | 20.05 ± 4.32 | 21.67 ± 6.75 | .663 |

| PANSS negative | 18.04 ± 9.33 | 14.26 ± 7.01 | 19.89 ± 9.68 | .163 |

| PANSS general psychopathology | 35.15 ± 11.92 | 32.22 ± 6.19 | 35.78 ± 9.64 | .489 |

| PANSS total | 73.08 ± 20.33 | 66.55 ± 13.67 | 77.33 ± 21.30 | .263 |

ANOVA test or chi-squared test used, as appropriate.

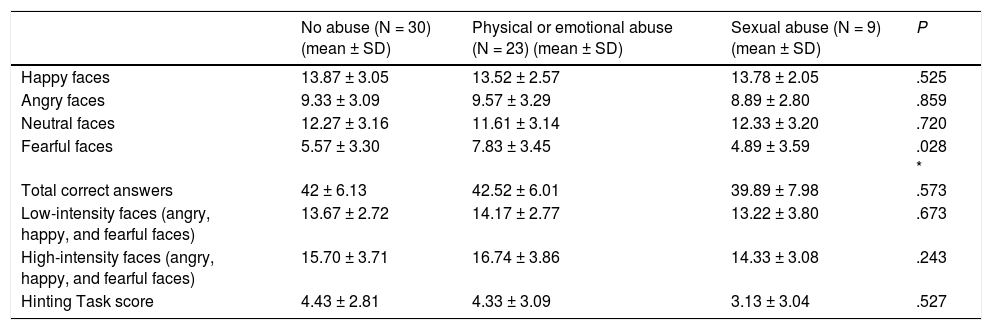

We first analysed intergroup differences in emotion recognition (ie happiness, fear, anger, neutral). We did not find any differences between groups in terms of the recognition of happy faces, angry faces, or neutral faces, nor in total score (degraded or high-intensity form). We also failed to find differences in Hinting Task scores. However, we did find differences in fearful-expression recognition (P = .028) between groups. The post hoc analysis for this task revealed that there were not differences between non-abused and sexually abused groups (P = .859) and a trend to statistical significance was found when comparing the group without abuse and the physical or emotional abuse group (P = .050) and between physical or emotional abuse group and sexual abuse group (P = .079). Table 2 shows these results.

Differences in emotion recognition and Hinting Task performance between abuse groups.

| No abuse (N = 30) (mean ± SD) | Physical or emotional abuse (N = 23) (mean ± SD) | Sexual abuse (N = 9) (mean ± SD) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Happy faces | 13.87 ± 3.05 | 13.52 ± 2.57 | 13.78 ± 2.05 | .525 |

| Angry faces | 9.33 ± 3.09 | 9.57 ± 3.29 | 8.89 ± 2.80 | .859 |

| Neutral faces | 12.27 ± 3.16 | 11.61 ± 3.14 | 12.33 ± 3.20 | .720 |

| Fearful faces | 5.57 ± 3.30 | 7.83 ± 3.45 | 4.89 ± 3.59 | .028 * |

| Total correct answers | 42 ± 6.13 | 42.52 ± 6.01 | 39.89 ± 7.98 | .573 |

| Low-intensity faces (angry, happy, and fearful faces) | 13.67 ± 2.72 | 14.17 ± 2.77 | 13.22 ± 3.80 | .673 |

| High-intensity faces (angry, happy, and fearful faces) | 15.70 ± 3.71 | 16.74 ± 3.86 | 14.33 ± 3.08 | .243 |

| Hinting Task score | 4.43 ± 2.81 | 4.33 ± 3.09 | 3.13 ± 3.04 | .527 |

Kruskal-Wallis test or ANOVA test, as appropriate.

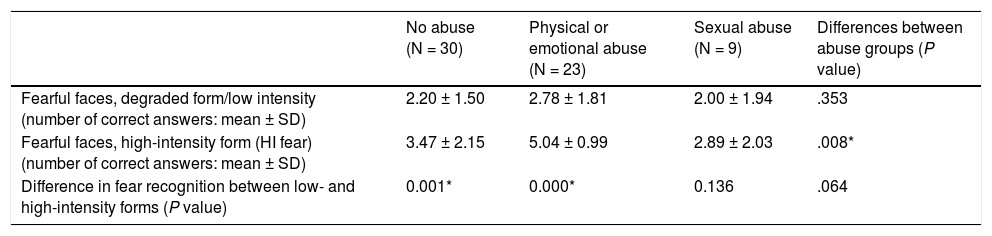

When we studied these differences taking into account differences variations in intensity of the images, we found no differences between groups in the recognition of fear when the degraded image (low intensity) was used (P = .353). Differences were present in the recognition of high-intensity fear (HI fear) presentation (without image degradation) (P = .008), as scores in the non-abused group were similar to those of the group of sexual abuse, and differences were found compared to the group comprising individuals who had been subjected to physical, emotional, or psychological abuse. Differences between groups are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1. We also studied the improvement in emotion recognition due to higher image intensity (differences in emotion recognition between low-high-intensity form). We did not find differences between abuse groups regarding the improvement of happiness recognition (P = .203), anger recognition (P = .650), or in total face score (expressing fear, anger, and happiness) (P = .443). When we studied difference between groups in the improvement of fear recognition, this difference tended toward significance (P = .064), so we studied this improvement within each group; only the sexually abused group did not show a significant improvement in fear recognition when the intensity of the image was higher. Results are shown in Table 3.

Differences in fear recognition.

| No abuse (N = 30) | Physical or emotional abuse (N = 23) | Sexual abuse (N = 9) | Differences between abuse groups (P value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fearful faces, degraded form/low intensity (number of correct answers: mean ± SD) | 2.20 ± 1.50 | 2.78 ± 1.81 | 2.00 ± 1.94 | .353 |

| Fearful faces, high-intensity form (HI fear) (number of correct answers: mean ± SD) | 3.47 ± 2.15 | 5.04 ± 0.99 | 2.89 ± 2.03 | .008* |

| Difference in fear recognition between low- and high-intensity forms (P value) | 0.001* | 0.000* | 0.136 | .064 |

Although we did not find differences for any of the variables, we adjusted for sex by taking into account sex-based differences in social cognition described previously in literature.9,11 We did not include other factors in the analysis because a previous intergroup analysis did not show significant differences between abuse groups in age, years of education, or PANSS factors (Table 1). After the adjustment was made, sex did not show significance (P = .860), and the differences between groups remained significant (P = .013).

Differences between groups in fear misinterpretationWhen we analysed differences between groups in misinterpretations of fear, we found differences between groups with previous abuse concerning instances in which faces expressing fear were misinterpreted as neutral (P = .03); in a post hoc analysis, we found that the sexual abuse group tended to misinterpret fear as neutral with greater frequency than did the physical or emotional abuse group (P = .040), though the same was not found between other groups (P = .531 between the sexual-abuse and non-abuse group, and P = .120 between the non-abuse and physical or emotional abuse groups). We did not find differences between groups for cases in which faces expressing fear were interpreted as angry (P = .883) or happy (P = .148).

DiscussionMain findingsWe found differences between abuse groups in fear recognition. According to our results, psychotic patients with a history of childhood trauma other than sexual abuse recognized fearful facial expressions more accurately than participants with a history of sexual abuse or without a history of childhood trauma. Unlike the other groups studied, psychotic patients with previous sexual abuse did not improve in their ability to recognize fear at higher image intensity (although differences between groups did not reach statistical significance). These individuals tended to misinterpret fear faces as neutral faces with greater frequency than those with previous, non-sexual abuse, though this frequency was not greater than that seen in non-abuse group. We have not found other differences between abuse groups, neither with regard to the recognition of other emotions nor in clinical symptoms (PANSS factors) nor in Hinting Task scores.

Comparison with previous studies and possible explanationsThere is a wealth of literature on the relation between childhood trauma and psychotic disorders in adulthood, though few works explore how trauma affects social cognition in people with psychotic disorders. Both early-life stress and psychotic disorders have been associated with changes such as increased HPA axis response, elevated striatal dopamine, and greater activation to later life stress.39,40 Lardinois et al.,41 in a sample of individuals with psychosis, described that those with previous exposure to adversity are more responsive to later stress, instead of more resistant. Reininghaus et al.42 found an association between threat anticipation and psychotic experiences in individuals with first episode of psychosis and high levels of sexual abuse, though the authors reported the opposite effect in controls, with less intense negative emotional reactions and threat anticipation to environmental stress in individuals exposed to high levels of sexual abuse. Pollak et al.,43 in a sample of nine years old children, described that those with high levels of parental anger and physical abuse recognized anger earlier (task consists in progressive images adopting a fearful, anger, sad, happy or surprised emotion), although another recent study did not find association between childhood adversity and emotion recognition in a non-clinical sample of children.44 These results are consistent with those found in our sample, as we found that the individuals with childhood trauma other than sexual abuse had better recognition of fearful faces in the DFAR task.

Dissociation is characterized by a range of anomalies in core perceptions of oneself and the world, and with a compartmentalization of psychological functions of identity.45 Dissociation has been proposed as a mediator between childhood trauma and such psychotic symptoms as hallucinations.46,47 This role as mediator is particularly robust for sexual abuse when compared to other types of trauma.48 Sexual abuse was also associated with greater levels of dissociation in adults with schizophrenia.48,49 In a similar way, Lysaker et al. reported that patients with schizophrenia who were aware of their own emotions and not those of others had higher reports of sexual abuse.50 Depression and anxiety have also been proposed to have a mediating function between childhood sexual abuse and psychosis.21 Individuals with a history of sexual abuse in our sample were less able to recognize expressions of fear on faces than those with childhood trauma other than sexual abuse. These individuals tended to misinterpret them as neutral faces, and their ability to recognize facial expressions of fear failed to improve when the images were clearer. This difficulty in recognizing fear may be related to the process of dissociation and difficulty in reading other mental states, which have been linked to sexual abuse. Our findings did not provide sufficient support to confirm this hypothesis, as we do not have information about dissociative symptoms in our sample.

We only found one previous work analysing differences in social cognition among individuals with psychotic disorders stratified by different types of childhood trauma. In the study, García et al.25 use a different task that evaluates the ability to manage emotions. They found worse social cognition to be associated with physical and emotional neglect,25 finding no association with sex. We use, in this work, measures of other social cognition domains (emotion recognition and theory of mind), hence our results and theirs are not comparable.

We did not find differences in symptoms (PANSS factors) between groups. A previous study by Ajnakina et al.,51 in a sample of 236 patients with first episode of psychosis, reported an association between positive symptoms and child sexual abuse, physical abuse, and parental separation. They also found more symptoms of excited dimension in people that were being taken into care in childhood. Our sample is smaller than that, and we did not use the same factors for our analysis of PANSS symptoms. Additionally, we classified types of childhood trauma differently, which may explain our failure to find the same association. Other researchers have found higher severity of positive symptoms in psychosis in individuals with early childhood trauma,52,53 though we found no such differences in our sample. We did not find differences in depressive or anxiety factors between the abuse groups. We do not have other information about affective or anxiety symptoms beyond PANSS factors, so this could also be a limitation of our study.

We also did not find differences in theory of mind performance between groups. A recent study in individuals with psychotic disorders described differences in the activation of brain regions while the psychotic subjects completed a theory of mind task associated to previous childhood trauma exposure, though no differences were observed in task performance.54 The authors did not analyse differences between types of trauma.

Strengths and limitationsA key component of this study concerns the division of study participants by childhood trauma type. Many individuals with psychotic disorders report more than one kind of trauma during childhood. In our sample, 6 of 9 individuals in the sexual abuse group also had a history of other types of trauma (defined as a score >3). Specific adversities rarely occur in isolation, so we attempted to separate the effect of one type of trauma, namely, sexual abuse, from the effect caused by other trauma types so as to have more information about the particular effects of sexual abuse. Our questionnaire on childhood trauma only inquired about sexual abuse with contact (being touched or forced to touch), so we classified as present any positive answer on this item as other works did.19,50,55,56 In our sample, the group with a history of sexual abuse included a small number of individuals. Our sample size is also a limitation of this study and, because of this, our results should be interpreted with caution.

In order to minimize the effect of chronicity, we only included subjects with less than five years of illness. In previous studies, social cognition has been shown to be a trait marker57 that is present in early stages58 and independent of the course of the illness.59,60 In line with other studies25,51,61 we included people with psychotic disorders (DSM-IV TR psychotic codes 295-298).

Another possible limitation of our study stems from the fact that childhood trauma was recorded retrospectively and was self-reported. This has been previously studied showing to be stable over time and not influenced by current mental state in psychosis patients,62 but memories of traumatic events may not be completely reliable; rather, they may be supressed or modified by subsequent experiences or emotional components. This is a bias to consider in trauma studies.15

We do not have information about pharmacological treatment in these individuals, so this could also be a limitation of our study. We also did not collect additional information about childhood situations, such as adoption, time spent living in an institution, or previous immigration, which could also influence these results. This is a limitation of our study and should be taken into account in further research.

ConclusionWe found differences in fear recognition among individuals with psychotic disorders based on the type of childhood trauma the subjects had experienced, revealing that individuals with childhood trauma other than sexual abuse performed better when recognizing fear. In our sample, the group with a history of sexual abuse tended to misinterpret expressions of fear as neutral, and their ability to recognize fear failed to improve with greater image intensity. There is a well-established association between childhood trauma and psychotic disorders, particularly when the trauma involves sexual abuse. Knowledge of the way these events lead individuals to develop a psychotic disorder or become more prone to psychosis remains largely unclear. Studying clinical differences between individuals with different reports of trauma helps us learn more about the different effects that these experiences have, and could lead to a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in psychotic disorders. More studies are required to confirm these differences and study the effects of childhood trauma on social cognition and proneness to psychosis.

FundingThis study was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), grant FIS PI11/02334.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding this study.

We thank Oliver Shaw for assistance with the English review of this work.

Please cite this article as: Brañas A, Lahera G, Barrigón ML, Canal-Rivero M, Ruiz-Veguilla M. Efectos del trauma infantil en el reconocimiento de la expresión facial de miedo en psicosis. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2022;15:29–37.