Although impulsivity may seem to be strongly linked to bipolar disorder, few studies have directly measured this phenomenon. To determine its implications for the prognosis of this illness, we studied the relationship between impulsivity and other aspects that are probably related, such as sensation seeking and aggressiveness, and different clinical variables of bipolar disorder.

MethodSixty-nine (type I, n=42; type II, n=27) outpatients from a unit specifically for bipolar patients in remission completed the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS), the Sensation Seeking Scale (SSS), the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI) and the Bipolar Eating Disorder Scale (BEDS). Sociodemographic and clinical data were obtained.

ResultsType II bipolar patients scored significantly higher on the BIS and the BDHI physical aggression subscale. Patients with predominant depressive polarity also obtained significantly higher global scores on the BDHI. No differences were found relating to prior suicide attempts or psychiatric admissions. Smoking patients scored significantly higher on the BIS non-planning subscale and the SSS disinhibition subscale.

LimitationsAs patients with substance use disorder (SUD) were excluded, the sample of this study may represent a subgroup of patients with bipolar disorder with probably low levels of impulsivity.

ConclusionsImpulsivity and aggressiveness are relevant aspects of bipolar disorders that could significantly increase comorbidity, especially in type II bipolar patients. Adequate diagnosis and treatment are, therefore, important factors in improving the clinical course of this illness.

Aunque la impulsividad puede aparecer fuertemente relacionada con el trastorno bipolar, pocos estudios han medido directamente este fenómeno. Con el objetivo de conocer sus implicaciones pronósticas, estudiamos la relación entre la impulsividad y otros aspectos probablemente relacionados con ella, como son la búsqueda de sensaciones y la agresividad y diferentes variables clínicas del trastorno bipolar.

Métodos69 pacientes ambulatorios en remisión (tipo I, n=42; tipo II, n=27) de una unidad específica de trastornos bipolares completaron la Escala de Impulsividad Barratt (BIS), la Escala de Búsqueda de Sensaciones (SSS), el Inventario de Hostilidad de Buss–Durkee (BDHI) y la Escala para las Alteraciones de la Conducta Alimentaria en el Trastorno Bipolar (BEDS). Se obtuvieron datos clínicos y sociodemográficos.

ResultadosLos bipolares tipo II obtuvieron puntuaciones significativamente más elevadas en la BIS y en la subescala de agresividad física del BDHI. En los pacientes en los que predominaba la polaridad depresiva, las puntuaciones globales en el BDHI eran significativamente más elevadas. No se encontraron diferencias en función de los antecedentes de intentos de suicidio o de ingresos psiquiátricos. Los pacientes fumadores puntuaron de forma significativamente más alta en la Subescala de no planificación de la Barratt y en la Subescala de desinhibición de la SSS.

LimitacionesDado que los pacientes con abuso de sustancias fueron excluidos, la muestra de este estudio puede representar un subgrupo de pacientes bipolares con niveles más bajos de impulsividad.

ConclusionesLa impulsividad y la agresividad son aspectos relevantes en los trastornos bipolares que podrían incrementar de un modo significativo la comorbilidad, especialmente en subtipo II. Por lo tanto un adecuado diagnóstico y tratamiento de ambos son importantes a la hora de mejorar el curso clínico de esta enfermedad.

The definition of impulsivity is a complicated matter; in fact, although the DSM-IV gives some examples of impulsive behaviour,1 impulsivity is not clearly defined. This lack of specificity has given rise to disagreements in the literature as to how to define it and measure it.2 This concept may also have different meanings: it may be included among the symptoms for a great many psychiatric disorders; it may also be considered a personality trait appearing in certain personality disorders; or it may refer to a specific type of aggression. According to Eysenck, the term impulsivity reflects a maladaptive behaviour pattern governed by motor activation, precipitate behaviour, lack of planning, snap decisions, and a tendency to act without thinking.3 From a biopsychosocial standpoint, Moeller et al.2 define it as a predisposition toward unplanned quick reactions to internal or external stimuli, where the individual does not foresee the negative consequences of this behaviour for himself or for others.

The largest survey conducted on this issue in bipolar patients—the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)—found that 56.1–71.2% of the bipolar patients included had a history of at least 1 comorbid impulse control disorder over the course of their life.4

As measured using the Barratt scale,5 impulsivity is noted to increase interepisodically in bipolar disorder, independent of manic episodes.6,7 In a study on impulsivity conducted with 108 type I bipolar patients in manic or mixed state, Strakowski et al. found a number of changes on various impulsivity assessment tests linked to the manic phase that were normalized during the euthymic and depressive phases—in contrast to what happened with the high Barratt scores—which shows that impulsivity has components dependent on not only the patient's affective state but also the trait.8 Like the mixed states in bipolar disorder,10 depressive episodes are also associated with impulsivity—especially if suicidal behaviour is present.9

With regard to biological factors, there are differences between patients who are impulsive-aggressive and those who are not; in fact, Moeller's review2 suggests that impulsivity and bipolar disorder can be related in 5 different ways. First, in patients previously diagnosed with attention deficit disorder (in whom greater impulsivity has been demonstrated), there would be a susceptibility to mania. Second, increased impulsivity would be associated with the prodrome of maniform states—that is, it may accompany these states or appear, initially, as part of the prodrome. Other ways they could be related are as a greater risk of complications such as suicide9 or substance abuse10 and, lastly, in connection with the response to treatment and pathophysiology of the disease, such as failures in prefrontal cortex functioning,12 diminished serotonergic functioning,13 and increased adrenergic functioning.14

As we have pointed out, in bipolar disorder, impulsivity has components that are dependent on not only the “state” (manic or depressive episode) but also the “trait” (continued pattern). The “state” component is reflected as more errors on certain tests, such as the Immediate Memory Task—Delayed Memory Task (IMT-DMT). The responses for impulsivity on this test correlate to subsyndromal manic symptoms and may be related to noradrenergic function, which is increased in manic phases.14,15 The “trait” component, on the other hand, would correlate with biologically stable measurements of impulsivity, such as serotonergic functioning.14 From this it may be inferred that impulsivity, as measured using the Barratt scale, may be a stable feature of bipolar disease.6

When impulsivity is associated with bipolar disorder, the complications that may appear are numerous, including suicide,16,17 substance abuse,18,19 increased comorbidity,20 and deterioration in the social, family, and employment realms, together with a higher risk of accidents and violence.21 There is also a clear association between impulsivity22,23 and some eating behaviour disorders that may appear comorbidly with bipolar disorder, especially between bulimia and subtype II24,25 and also with overeating disorders.26

There are other factors of interest, such as sensation seeking and aggressiveness that should be taken into account when studying the correlation between bipolar disorders and impulsivity. In terms of phenomenological characteristics, impulse control disorders and bipolar disorders have some features in common, such as risk seeking, sensation seeking, and seeking pleasurable activities. Regarding aggressiveness, various studies have found a significant correlation between scores on impulsivity scales and scores on aggressiveness scales.27,28 However, except for some studies focused on comorbidity between bipolar disorder and personality disorder,29 the correlation between impulsivity and aggressiveness in bipolar patients has scarcely been explored,30 nor has the quantitative correlation between impulsivity and the course of bipolar disease been analysed.31

The objective of our study was to investigate the correlation between impulsivity and different clinical variables in bipolar disease and, simultaneously, to investigate the association with features such as sensation seeking and aggressiveness.

Materials and methodsA total of 69 patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder participated (type I, n=42; type II, n=27), all of whom were under outpatient treatment in a specialized Bipolar Disorders Unit at Hospital la Fe. The inclusion criteria were (1) being diagnosed with bipolar disorder per the DSM-IV1 and (2) being in clinical remission for at least the 6 months prior to the study. The exclusion criteria were (1) meeting the criteria for substance abuse at the time of the evaluation or during the previous 6 months and (2) having undergone medication changes during the last 2 months. In the evaluation, patients completed the self-report scales described below, and the clinician completed the Hamilton Scale32 and the EVMAC33 [Escala de la Valoración de la Manía por Clínicos/Scale for Evaluation of Mania by Clinicians]. The EVMAC is a semi-structured interview that evaluates the severity of manic and psychotic symptomatology. The patients included were those who scored less than 7 on the Hamilton-D Scale and less than 7 on the EVMAC at the time the tests were completed, as well as over the course of the previous 6 months when they were being followed, this information being obtained from their medical record. Sociodemographic and clinical variables were obtained from the medical records, and any uncertainties were clarified through information given by the patient or, in some cases, by family members. Likewise, all the psycho-active drugs the patient was taking at that time were recorded under the following groups: lithium, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anxiolytics. All patients consented to the information being used.

ScalesThree self-report scales were used to evaluate impulsivity and features related to it, such as sensation seeking and aggressiveness. Self-report scales enable the researcher to obtain information about a variety of types of actions and whether these actions constitute long-term behaviour patterns.

The Barratt Impulsivity Scale is a self-report questionnaire that includes information from 3 different models: the psychological, the behavioural, and the social. It identifies 3 major factors—attentional, motor, and non-planning—reflecting the components of impulsivity11 and is one of the instruments most widely used in recent times for evaluating impulsivity. It consists of 30 items with point values from 0 to 4. Having shown internal consistency in its measurements, it has proven useful in both general and clinical populations. We used version 11, which has been adapted to Spanish.5 Mean scores for the Spanish population are as follows: cognitive subscale 9.5; motor subscale 9.5; non-planning subscale 14; and total 32.5.5

Sensation seeking scale: There are situations linked to impulsivity, such as sensation seeking, novelty seeking, and boredom susceptibility.34 This means that variety, novelty, and complexity of sensations are required to maintain an optimum activity level.35 This scale consists of 4 subscales made up of 10 items each: emotion seeking (BEM) or the seeking of physical sensations through danger and adventure; excitement seeking (BEX) or the seeking of new experiences through sensations and different lifestyles; disinhibition (DES) or the seeking of sensations through activities like using illicit drugs; and boredom susceptibility (SAB), which evaluates the poor tolerance for routine activities. The DES and SAB scales are those most related to the concept of impulsivity.36 This scale has been adapted to Spanish with acceptable reliability and validity.37 Mean scores for the Spanish population are 21.3 in men and 17.7 in women.37

The scale most frequently used for evaluating aggressiveness is the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory.38 It gives a dimensional measurement of the aggressiveness history, and the irritability subscale includes components relative to anger, hostility, and physical and verbal aggression, with items reflecting impulsive behaviour. It covers 4 components of aggressiveness: verbal aggression, physical aggression, anger, and hostility. The anger item is closely related to impulsivity. It consists of 75 items with 2 response options—true or false—and has been validated for Spanish.39 The proposed cut-off point is 27 points.39

For eating behaviour changes in bipolar disorder, we used the Bipolar Eating Disorder Scale (BEDS). This is a simple, self-report scale consisting of 10 items, with total scores ranging from 0 to 30 points—13 being the cut-off point for individualized intervention to be required. It enables the intensity and frequency of the different eating disorders to be evaluated.40

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS program, version 12.0. The bilateral statistical significance level used was .05. The comparison of clinical and sociodemographic variables was between bipolar type I and bipolar type II patients. The t-test was used for continuous variables with a normal distribution. For independent variables with more than 2 categories, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used.

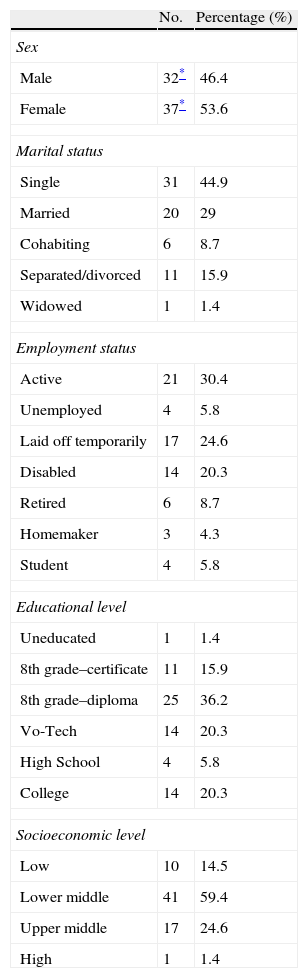

ResultsFor some of the analyses, the patients were divided into 2 groups by diagnosis: type I and type II bipolar disorders. In other cases, the analyses were performed for bipolar disorder overall, without specifying the type. No significant differences were observed (P>.05) between the bipolar I and bipolar II diagnosis for the variables of sex, marital status, employment status, socioeconomic level, and educational level. Sociodemographic variables are shown in Table 1 for both diagnoses together.

Sociodemographic variables for the sample.

| No. | Percentage (%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 32* | 46.4 |

| Female | 37* | 53.6 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 31 | 44.9 |

| Married | 20 | 29 |

| Cohabiting | 6 | 8.7 |

| Separated/divorced | 11 | 15.9 |

| Widowed | 1 | 1.4 |

| Employment status | ||

| Active | 21 | 30.4 |

| Unemployed | 4 | 5.8 |

| Laid off temporarily | 17 | 24.6 |

| Disabled | 14 | 20.3 |

| Retired | 6 | 8.7 |

| Homemaker | 3 | 4.3 |

| Student | 4 | 5.8 |

| Educational level | ||

| Uneducated | 1 | 1.4 |

| 8th grade–certificate | 11 | 15.9 |

| 8th grade–diploma | 25 | 36.2 |

| Vo-Tech | 14 | 20.3 |

| High School | 4 | 5.8 |

| College | 14 | 20.3 |

| Socioeconomic level | ||

| Low | 10 | 14.5 |

| Lower middle | 41 | 59.4 |

| Upper middle | 17 | 24.6 |

| High | 1 | 1.4 |

The patients were euthymic at the time the questionnaires were completed; they had not recently undergone any changes in treatment, nor had they been admitted within the last 3 months. Total EVMAC score 2.55±2.68 (subscales: mania 2.07±1.89, psychoticism 0.48±0.94), and Hamilton depression scale score 3.49±2.56.

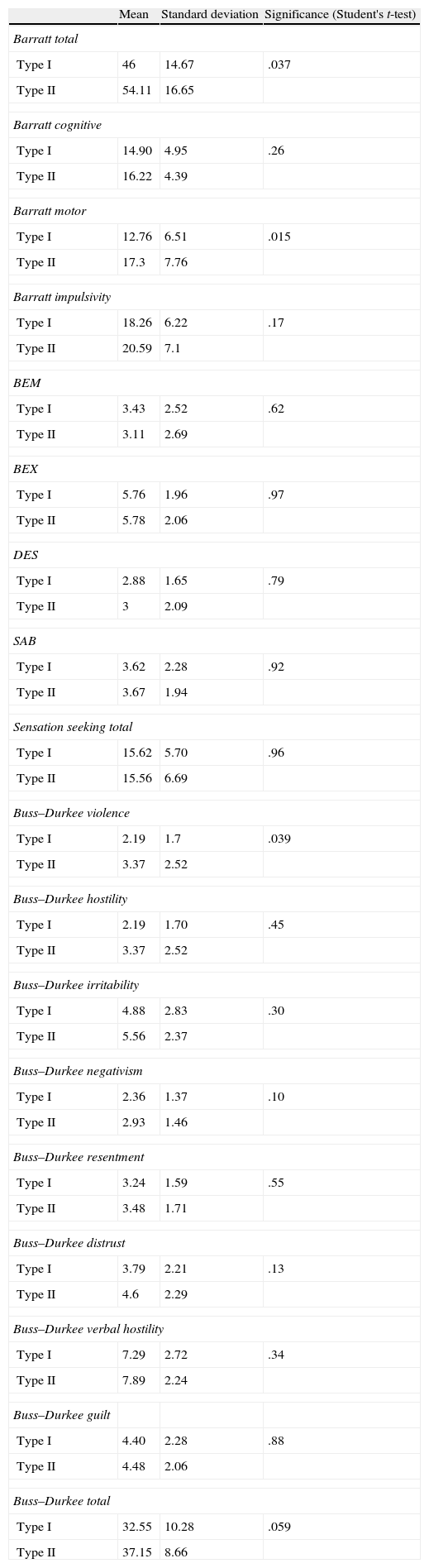

Comparison of the two diagnoses in terms of scores on the scales explained above revealed that bipolar II patients had statistically significant higher scores on the Barratt scale (Barratt total, P=.037; mean: 54.11; SD: 16.65; Barratt motor subscale, P=.015; mean: 17.3; SD: 7.76); there were no statistically significant differences on the sensation seeking scale; and there were significant differences for bipolar II patients on the violence subscale of the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory (P=.039; mean: 3.37; SD: 2.52) (Table 2).

Scores on the different scales for bipolar I and II patients.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Significance (Student's t-test) | |

| Barratt total | |||

| Type I | 46 | 14.67 | .037 |

| Type II | 54.11 | 16.65 | |

| Barratt cognitive | |||

| Type I | 14.90 | 4.95 | .26 |

| Type II | 16.22 | 4.39 | |

| Barratt motor | |||

| Type I | 12.76 | 6.51 | .015 |

| Type II | 17.3 | 7.76 | |

| Barratt impulsivity | |||

| Type I | 18.26 | 6.22 | .17 |

| Type II | 20.59 | 7.1 | |

| BEM | |||

| Type I | 3.43 | 2.52 | .62 |

| Type II | 3.11 | 2.69 | |

| BEX | |||

| Type I | 5.76 | 1.96 | .97 |

| Type II | 5.78 | 2.06 | |

| DES | |||

| Type I | 2.88 | 1.65 | .79 |

| Type II | 3 | 2.09 | |

| SAB | |||

| Type I | 3.62 | 2.28 | .92 |

| Type II | 3.67 | 1.94 | |

| Sensation seeking total | |||

| Type I | 15.62 | 5.70 | .96 |

| Type II | 15.56 | 6.69 | |

| Buss–Durkee violence | |||

| Type I | 2.19 | 1.7 | .039 |

| Type II | 3.37 | 2.52 | |

| Buss–Durkee hostility | |||

| Type I | 2.19 | 1.70 | .45 |

| Type II | 3.37 | 2.52 | |

| Buss–Durkee irritability | |||

| Type I | 4.88 | 2.83 | .30 |

| Type II | 5.56 | 2.37 | |

| Buss–Durkee negativism | |||

| Type I | 2.36 | 1.37 | .10 |

| Type II | 2.93 | 1.46 | |

| Buss–Durkee resentment | |||

| Type I | 3.24 | 1.59 | .55 |

| Type II | 3.48 | 1.71 | |

| Buss–Durkee distrust | |||

| Type I | 3.79 | 2.21 | .13 |

| Type II | 4.6 | 2.29 | |

| Buss–Durkee verbal hostility | |||

| Type I | 7.29 | 2.72 | .34 |

| Type II | 7.89 | 2.24 | |

| Buss–Durkee guilt | |||

| Type I | 4.40 | 2.28 | .88 |

| Type II | 4.48 | 2.06 | |

| Buss–Durkee total | |||

| Type I | 32.55 | 10.28 | .059 |

| Type II | 37.15 | 8.66 | |

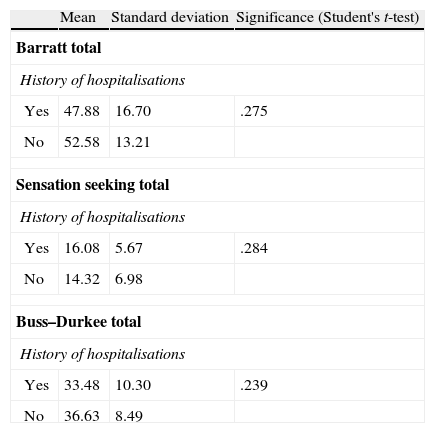

No differences were observed in the score on the different subscales in relation to whether there was a history of psychiatric hospitalisations (Barratt scale P=.275, sensation seeking P=.284, Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory P=.239) (Table 3). Although the BEDS scores were higher for bipolar II patients than for bipolar I patients (mean of 10.95 compared to 8.43), these differences were not significant (P=.125; SD=5.38 for bipolar I and 6.58 for bipolar II patients).

Distribution of scores on the different scales in relation to history of psychiatric hospitalisations.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Significance (Student's t-test) | |

| Barratt total | |||

| History of hospitalisations | |||

| Yes | 47.88 | 16.70 | .275 |

| No | 52.58 | 13.21 | |

| Sensation seeking total | |||

| History of hospitalisations | |||

| Yes | 16.08 | 5.67 | .284 |

| No | 14.32 | 6.98 | |

| Buss–Durkee total | |||

| History of hospitalisations | |||

| Yes | 33.48 | 10.30 | .239 |

| No | 36.63 | 8.49 | |

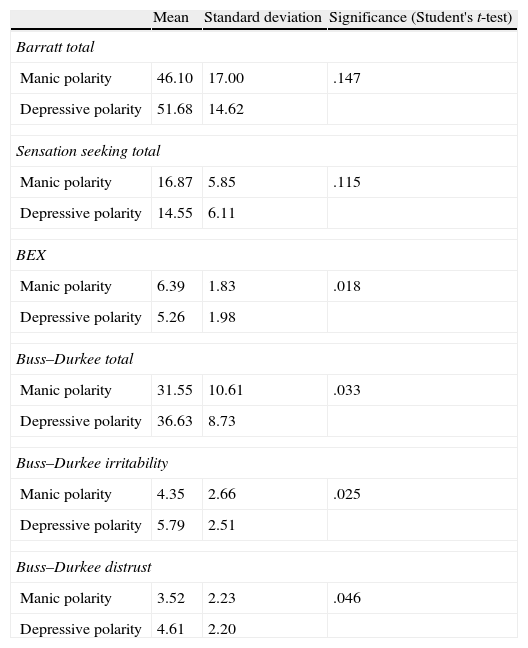

Other clinical and disease course variables, such as the predominant polarity, were analysed. The polarity was considered manic (or hypomanic, in the case of bipolar II patients) or depressive depending on whether at least 2/3 of past episodes met the DSM-IV criteria for one or the other type. It was found that patients whose predominant polarity was depressive had higher global scores on the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory (P=.033; mean: 36.63; SD: 8.73) as well as on the irritability subscale (P=.025; mean: 5.79; SD: 2.51) and the distrust subscale (P=.046; mean: 4.61; SD: 2.20). There were no differences on the Barratt; on the sensation seeking scale, the patients with manic polarity scored significantly higher on the BEX (P=.018; mean: 6.39; SD: 1.83) (Table 4).

Distribution of scores on the different scales in relation to dominant polarity.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Significance (Student's t-test) | |

| Barratt total | |||

| Manic polarity | 46.10 | 17.00 | .147 |

| Depressive polarity | 51.68 | 14.62 | |

| Sensation seeking total | |||

| Manic polarity | 16.87 | 5.85 | .115 |

| Depressive polarity | 14.55 | 6.11 | |

| BEX | |||

| Manic polarity | 6.39 | 1.83 | .018 |

| Depressive polarity | 5.26 | 1.98 | |

| Buss–Durkee total | |||

| Manic polarity | 31.55 | 10.61 | .033 |

| Depressive polarity | 36.63 | 8.73 | |

| Buss–Durkee irritability | |||

| Manic polarity | 4.35 | 2.66 | .025 |

| Depressive polarity | 5.79 | 2.51 | |

| Buss–Durkee distrust | |||

| Manic polarity | 3.52 | 2.23 | .046 |

| Depressive polarity | 4.61 | 2.20 | |

In connection with this aspect, the type of episode at disease onset was investigated; manic and depressive onsets were compared in terms of scores on the scales, but none of them turned out to be significant.

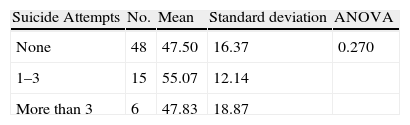

For the analysis of suicidal behaviour, patients were first categorized according to whether or not they had a history of suicide attempts and then according to the number of previous attempts: none, 1–3, or more than 3. No significant differences were found in any of the cases on the different scales using an analysis of variance (P=.270) (Table 5).

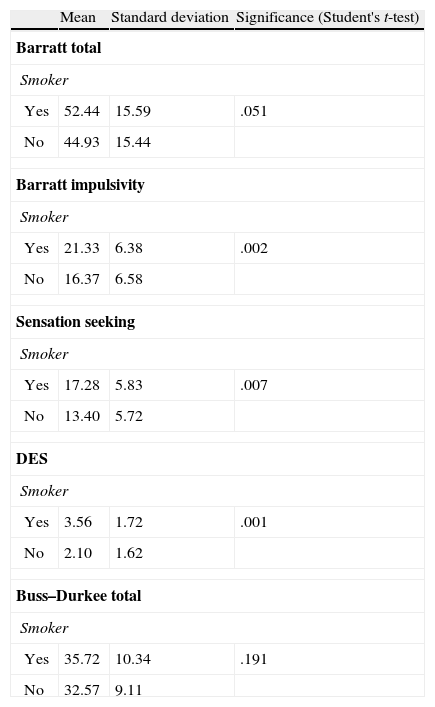

Evaluation of the impact of smoker status revealed no significant differences on the total Barratt scores (P=.051); however, differences were appreciated on some subscales when comparing smokers with non-smokers. Smokers scored significantly higher on the Barratt impulsivity subscale (P=.002; mean: 21.33; SD: 6.38), on total sensation seeking (P=.007; mean: 17.28; SD: 5.83), and on the DES (P=.001; mean: 3.56; SD: 1.72) (Table 6).

Distribution of scores on the different scales in relation to smoker status.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Significance (Student's t-test) | |

| Barratt total | |||

| Smoker | |||

| Yes | 52.44 | 15.59 | .051 |

| No | 44.93 | 15.44 | |

| Barratt impulsivity | |||

| Smoker | |||

| Yes | 21.33 | 6.38 | .002 |

| No | 16.37 | 6.58 | |

| Sensation seeking | |||

| Smoker | |||

| Yes | 17.28 | 5.83 | .007 |

| No | 13.40 | 5.72 | |

| DES | |||

| Smoker | |||

| Yes | 3.56 | 1.72 | .001 |

| No | 2.10 | 1.62 | |

| Buss–Durkee total | |||

| Smoker | |||

| Yes | 35.72 | 10.34 | .191 |

| No | 32.57 | 9.11 | |

Upon analysing the scores according to treatments, no differences were observed between patients taking lithium and patients not taking lithium. In the case of the antipsychotics, statistically significant differences were found on the Buss hostility subscale, with patients taking antipsychotics scoring significantly higher (P=.032, 4.94±0.33, compared to 4.17±0.16), and the resentment subscale (P=.005), also in those who were taking them (4.13±1.08 compared to 3.06±1.69).

Regarding the comparison between patients taking and patients not taking antidepressants, those not taking them scored significantly higher on the global sensation seeking scale (P=.040, with scores 12.64±5.32 compared to 16.35±6.05).

As for treatment with anxiolytics, the patients who were taking them scored significantly higher on the global Hostility scale (P=.003 38.85±9.55, compared to 31.63±9.14), as well as on the subscales for irritability (P=.017 6.12±2.53 compared to 4.56±2.59), resentment (P=.003, 4.08±1.46 compared to 2.88±1.57), and distrust (P=.05, 5.08±2.17 compared to 3.53±2.14).

DiscussionIn our study, we investigated factors that, through an increase in impulsivity and aggressiveness, could heighten the risk of comorbidity in bipolar disorder, among them being the bipolarity subtype, the patient's smoker status, and the predominant polarity.

There are a number of psychiatric disorders in which impulsivity is more frequently seen, such as mania, personality disorders, and substance abuse.2 In bipolar disorder, impulsivity is among the diagnostic criteria for mania listed in the DSM-IV.1 Studies analysing the impact of gender on impulsivity have found no differences. It appears that, at young ages, impulsivity levels are higher in boys,41 but in adulthood they are equal.6,42 Adolescents at risk for mania, who were evaluated in a semi-structured interview, were noted to have increased impulsivity, so this may be part of affective episodes and may even appear before these patients have a definite diagnosis.43

In our study, we found that patients with type II bipolar disorder scored higher on the Barratt impulsivity scale and on the violence subscale of the Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory. Previous studies report a high percentage of comorbidity in this patient subgroup,44 with anxiety disorders,45 substance abuse disorders,46 eating disorders,24 personality disorders,47 and obsessive-compulsive disorders.48 The proposed hypothesis could be that the higher impulsivity levels seen in the bipolar type II subgroup favour comorbidity. Discovering those factors that influence the disease course in this subgroup is important because their quality of life has been found to be diminished in comparison with bipolar I patients.49

Impulsivity also means a higher risk of complications with some factors in the impulse control disorders spectrum, such as substance abuse. It appears that, as a trait, impulsivity is increased to a similar extent in substance abuse and in interepisodic bipolar disorder, with a greater increase in those patients suffering from both conditions.6 None of the patients in our study met the criteria for substance abuse; however, patients who were smokers scored higher on the Barratt impulsivity subscale, which is consistent with previous studies that found smokers to be more impulsive than non-smokers.50

In our study, we found no association between the impulsivity level, as measured on the Barratt, and the history of suicide attempts—considering whether there were any attempts, or else the number of attempts. However, as described above, there was a positive association in patients with affective disorders.51 It has been observed that patients who have attempted suicide repeatedly differ in various clinical respects from patients who have made only one attempt.52 It is possible that, because impulsivity is intrinsically heightened in bipolar disorder, it is less useful as a marker for suicide risk in this population.21 In our study, no differences were observed between the two variables. A history of suicide attempts has been associated with impulsive responses on immediate memory tasks—especially in cases of serious, medical-level attempts53—but not with higher scores on the Barratt scale.54 Swann found that the Barratt scores were numerically higher in bipolar patients with a history of suicide attempts, which suggests that, in a group of subjects, there could be a correlation between the scores and the history of previous attempts but not the severity of the attempts.53 In bipolar children and adolescents, multifactorial correlations, such as aggressive tendencies, impulsivity, and risk behaviours have been described as powerful indicators of suicide risk.55 In fact, it is recommended that, in addition to obtaining information about suicidal behaviour, clinicians should evaluate patients for pessimistic traits and aggressive/impulsive traits so that they are better able to identify patients at risk for suicide following a major depression.56

In a study that evaluated the differential characteristics between bipolar patients with and bipolar patients without a history of suicidal behaviour, a stronger history of aggressiveness was found in patients who had made previous attempts compared to those who had made no attempts; there was no difference in the impulsivity level,28 however, in contrast to unipolar depressed patients, where both parameters were elevated.57

It has been found that novelty seeking is more elevated in bipolar patients in a euthymic phase than in unipolar and control patients.58 In our study, we found no differences in scores between bipolar I and bipolar II patients.

With regard to eating disorders, there is a particularly high comorbidity between subtype II and bulimia.25 Major correspondences between the two disorders have been identified, as well—an overlapping in numerous features, for example, such as mood and the deregulation of eating, impulsivity and compulsivity, or craving for activity and/or exercise.24 In our study, neither group's scores exceeded the cut-off point of 13 proposed by the authors, above which individualized intervention and treatment is recommended40; it was found, however, that type II bipolar patients scored higher on the BEDS (10.95) than type I bipolar patients (8.43).

Upon analysing the correlation between the patients’ dominant polarity and their score on the different scales, we found that, when the predominant polarity was depressive—defined as at least 2/3 of the patient's previous episodes meeting the DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode59—the patients scored higher on aggressiveness scales, both globally and on the irritability and distrust subscales. An article investigating the correlation between impulsivity and manic symptoms during episodes of bipolar depression reports that high scores on the Barratt reflect increased impulsivity as a trait—not limited to the current episode—suggesting that depressed patients with mixed symptomatology are more susceptible to impulsivity over the long-term and have a more complicated disease course.10 One possible explanation for our findings is that patients whose predominant polarity is manic are more often prescribed Class A mood stabilizers (the so-called “from above” stabilizers), which act by masking symptoms of aggressiveness.

With regard to therapeutic approach, due caution should be used when considering the results; however, we did take into account the scores on the different scales and whether there was concomitant therapy with a number of drugs. In the case of lithium, although it has been described as a good drug for reducing impulsivity,60 we found no difference. Valproic acid has been reported to be more effective than lithium for those cases of manic patients who have more dysphoria and irritability; superior to placebo in controlling symptoms of impulsivity and hostility; and equal to lithium in reducing hyperactivity.61 In other words, there are different subtypes of mania with different responses to treatment.62 The main problem is that it is associated with worse functioning between phases, including an increased risk of therapeutic non-compliance.

As for the antipsychotics, differences were found on the Buss hostility and resentment subscales, the patients on these drugs scoring significantly higher. Although some studies suggest that they are effective in patients with impulse control disorders,63 they should be used only when other measures, such as the anticonvulsants, lithium, and beta blockers, have failed.64

According to our results, patients who were not taking antidepressants scored significantly higher on the global sensation seeking scale. Drugs that boost serotonergic functioning, specifically, are effective in diminishing aggressive impulsive behaviour. Low serotonergic functioning increases aggressiveness and impulsivity.65 It is really difficult to interpret these findings: they could raise the question of whether the results of this scale—which evaluates the need for sensations and new, varied, and complex experiences that includes a desire to take risks to obtain them—might reflect subclinical hypomanic symptoms in some patients.

With regard to anxiolytic therapy, patients who were taking these drugs scored significantly higher on the global hostility scale and on the irritability, resentment, and distrust subscales.

Multiple and varied strategies have been used in treating impulsivity—empirically, in almost all cases, because there are very few controlled studies. Generally speaking, no clear correlation was found between the treatments and the scores on the different scales. Paradoxically, those patients who were taking the drugs mentioned scored higher on various scales, probably because these patients were the more severe cases, clinically. These results are consistent with previous studies that have reported a lack of correlation between medication and Barratt scores.31

As for limitations of the study, because patients with substance abuse were excluded, the sample may represent a subgroup of bipolar patients with lower impulsivity levels. The results on the impact of medications are preliminary because the study did not take into account the dosage prescribed, the possible effect of drug combinations, or the different subtypes (SSRIs or tricyclics, classic or atypical antipsychotics). Lastly, the patient sample was small relative to the number of variables investigated, which limits the power of the study's statistical analyses.

In conclusion, given that aggressiveness and impulsivity are major aspects of the affective disorders, managing them should be considered a basic element of the approach to bipolar disorder. Our results indicate that proper diagnosis accompanied by more specific treatment of impulsivity would improve the prognosis by reducing comorbidity—the strongest predictor of poor therapeutic compliance.66

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sierra P, et al. Impulsividad, búsqueda de sensaciones y agresividad en pacientes bipolares tipo I y II. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2011;4:195–204.