Understanding if there are differential determinants of objective and subjective burdening in caregivers of first episode psychosis (FEP) patients would be essential to optimize current early support programs. Our aim was to elucidate the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of FEP patients that influence the objective and subjective burdening of their informal caregivers.

Materials and methods75 participants with FEP were assessed in social functioning and psychotic symptoms. Their caregivers were assessed with an instrument of objective and subjective family burden. Objective burdening was assessed in terms of time spent. Subjective burden was assessed in terms of worry experienced.

ResultsRegression analyses showed that impaired social functioning of the patient was the major determinant of family burdening, in assisting in daily activities and containing disrupted behavior. Excitative symptoms were more determinant than positive symptoms in explaining burdening when containing disrupted behavior. A younger age of the patient specifically determined higher subjective but not objective burdening. Economic incomes had little contribution to family burdening.

ConclusionsOur results suggest that there may not be differential determinants of objective and subjective burdening on domains of family burdening in FEP. Current multicomponent early interventions may consider social functioning and excitative symptoms the factors that may focus on to reduce both objective and subjective family burdening. Caregivers of youngest patients may need additional psychological support as they care of patients with higher dependency level and involving more subjective burdening.

The onset of psychosis and its treatment is often traumatic and overwhelming for families.1 During this period, family members usually become the informal caregivers of their relatives with first episode psychosis (FEP) and play an important role in the process of recovery and the prevention of relapse of the patients, which is demonstrated by a recent network meta-analysis that shows that family interventions are among the most effective psychological interventions of relapse prevention in psychosis.2 Informal caregivers commonly suffer high levels of stress and subjective feelings of burden.3 The term ‘family burden’ is a complex construct that scopes different domains, ranging from family routines to number of caring hours, social support networks and out-of-pocket expenses. This burden implies both subjective (e.g., psychological impact) and objective (e.g., social restrictions or economic demands) factors. The informal caregivers of people with FEP report a strong emotional impact of the caring process, which alongside a lack of perceived personal resources to face the illness-related symptoms of their relatives may result in delays and troubles for seeking treatment.4 Moreover, if not adequately supported from health services, the informal caregivers of FEP may have their mental and physical health adversely affected,5 and also lose work productivity.6

Most studies evaluating family burden focus on caregivers of people with established illness.7 The family impact may be distinct from that of caregivers of patients with FEP, given that each stage of the disorder may result in different caregiving demands. For instance, it has been reported that the most relevant domain in FEP caregivers is the emotional impact it involves.8

There are few studies that describe the clinical and psychosocial characteristics of patients that determine the family burden in informal caregivers of people with FEP, but the available literature suggests that positive symptoms and deteriorated psychosocial functioning of the patient appear to be its strongest determinants, both in cross-sectional6,9 and longitudinal studies.10 Moreover, qualitative studies found that informal caregivers expressed a great degree of concern if the relative suffered negative symptoms (included the abandonment of personal care), and disturbing and aggressive behaviors.11

There are subjective and objective components of caregivers’ burden. Available evidence suggests that subjective burden is explained mostly by the psychosocial functioning of the patient, while objective burden is determined by stigmatization or socioeconomic factors outside the clinical characteristics of the patient in prolonged psychosis.8,12,13

AimGiven these gaps in literature, the aim of this study is to elucidate the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of patients with FEP that influence the objective and subjective burdening of their informal caregivers.

MethodParticipantsThe data presented comes from the GENIPE study.14 All the patients enrolled in that study were consecutively invited to answer with their caregivers the family burdening questionnaire, and those who accepted where included in the analyses. The GENIPE study was comprised of 90 FEP patients, of whom 75 and their 75 corresponding caregivers agreed to take part in the current study. In general, patients were similar in terms on symptoms, gender and social functioning, with a tendency of accepting participants to be younger (mean age: 19.82 vs 25.00 in the group not answering the family burdening questionnaire, p=0.020). However, the reduced sample size and missing data of not accepting participants impedes to draw clear conclusions. The patients were recruited from adult mental health services at Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu and from the child and adolescent mental health services at the Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, either, which covers the Barcelona area in Spain.

The inclusion criteria for the patients were: presence of two or more psychotic symptoms; age between 7 and 65 years (final range of the sample between 13 and 39 years old); less than 6 months since the first contact with health services; and less than a year since development of symptoms as well as availability of a caregiver to perform the assessment. Patients diagnosed with intellectual disabilities (Premorbid IQ<70) or head injury were excluded from the study.

All selected individuals were informed of the study objectives and methodology by their psychiatrist or researcher and signed the informed consent form. In the case of children and adolescents, informed consent was obtained from their parents and from the service users themselves. The study was approved by the Sant Joan de Déu Independent Ethics Committee.

InstrumentsTwo trained psychologists conducted the assessments. Their inter-rater reliability of all the instruments was over 0.70 using the intraclass correlation coefficient between the two assessors.

Patient assessmentThe socio-demographic characteristics of the sample were assessed with an ad-hoc questionnaire. Economic incomes of both caregiver and patient were registered in terms of salary in euros per month. The diagnosis was obtained with the SCID Interview (First et al., 2002).

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)15,16Symptoms were assessed using the PANSS. Higher scores indicate a greater severity of psychopathology. We used the factor analysis proposed by Emsley et al.17 that divides the score into 5 domains: positive, negative, affective, disorganized, and excitative symptoms.

Disability Assessment Schedule, short version (DAS-sv)18This interview-based scale yields a total score from the assessment of general disability in four areas: self-care, occupational, family, and other areas of disability. We used the four areas for the analysis. A higher score indicates greater disability.

The Life Skills Profile (LSP)19,20LSP is an interview of 39 items and was used to assess social functioning in five domains: Self-Care (aspects related to ordinary duties); non-Turbulence (presence of disruptive behavior); Socialization (to what extent the patient is able to fluently interact); Communication (whether social communication skills are properly used); and, Responsibility (to what extent the patient is able to develop an autonomous lifestyle). We used the total score of the scale. A higher score indicates better social functioning.

The caregiver's assessmentObjective and Subjective Family Burden Interview (ECFOS-II)21We used 7 modules of this instrument includes assessing different areas of possible burden: module A (aid in activities of daily life); module B (containing altered behavior); module C (economic costs); module D (changes in caregiver routine); module E (reasons for patient worry); module F (hours of help given by another caregiver); module G (repercussions on the caregiver's health and psychoactive medication); Module A and B provide information about objective burden (time dedicated by the caregiver to covering this need) and subjective burden (worry). Module D includes information of objective burden and Module E includes information about subjective burden. Modules A, B, D, and E were summarized in quantitative variables. Module C could not be used in the analysis due to a high number of missing data. Module G and F are represented by 1 or 2 items, so are presented in terms of descriptives.

Data analysisAnalyses were conducted in three steps. First, we used descriptive statistics to describe the sample. Second, Pearson's correlations and mean differences tests were calculated to describe the association between each module of family burden (objective and subjective), sociodemographic factors (age of the patient, gender of the patient, economic incomes of family and patient), the symptoms and general disability, and the social functioning of the patient. Third, we built hierarchical multiple linear regressions to identify the sociodemographic, social and clinical factors of the patients that most contributed to explain the objective and subjective caregiver's burdening. The dependent variables were the modules of the ECFOS-II. We included as independent variables those that were significant at level p<0.05 in the bivariate analysis. On a first block, we included the sociodemographic factors. On second and third blocks, we included the social functioning and general disability factors, as they are the variables that have showed most consistent associations with caregivers’ burdening on previous studies. On the final block, we included the symptomatic factors. Multicollinearity was examined at each step. All the analyses were done using the jamovi 1.6 software.22

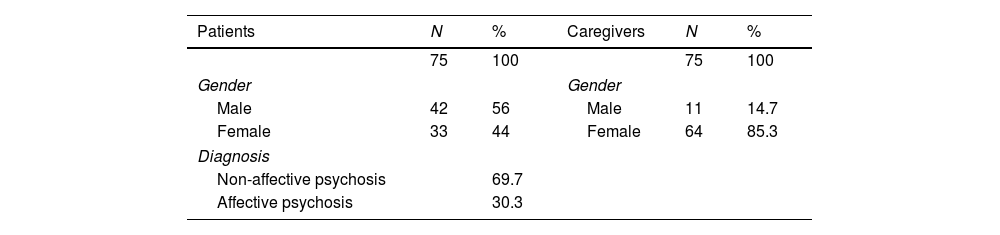

ResultsThe characteristics of the sample of FEP patients and their informal caregivers are presented in Table 1. Most of the FEP patients were young, with 75% of the group being under 22 years old. We replicated the results presented here with the subsample of patients under 22 years and were the same. Most patients lived with their parents (90.8% of the sample). Only 1 patient lived alone, 2 lived with their partner, 3 with own family with siblings, and 1 in other situations. The caregivers were mostly women, mothers, working, and with more than 28h of care during a week.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample of patients and caregivers.

| Patients | N | % | Caregivers | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 75 | 100 | 75 | 100 | ||

| Gender | Gender | ||||

| Male | 42 | 56 | Male | 11 | 14.7 |

| Female | 33 | 44 | Female | 64 | 85.3 |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Non-affective psychosis | 69.7 | ||||

| Affective psychosis | 30.3 | ||||

| Mean | SD (range) | Mean | SD (range) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19.82 | 5.96 | Age | 48.16 | 8.22 |

| Economic income | 306.25 | 494.58 (0–1600) | Economic income | 2298.80 | 1005.474 (600–5500) |

| Frequency of tobacco consumption | N | % | Relation caregiver to patient | N | % |

| Absence | 27 | 36 | Parent | 69 | 92 |

| Occasional | 4 | 5 | Spouse | 5 | 6.7 |

| Low intake | 6 | 8 | Other | 1 | 1.3 |

| Mean intake | 18 | 24 | Frequency of the relation | ||

| High intake | 19 | 26 | 1–7h/week | 9 | 12 |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | N | % | 8–14h/week | 11 | 14.7 |

| Absence | 26 | 35 | 15–21h/week | 9 | 12 |

| Occasional | 10 | 14 | 22–28h/week | 7 | 9.3 |

| 1 unit a month | 4 | 6 | >28h/week | 39 | 52 |

| 1 unit each week | 20 | 27 | |||

| More than 1 a week | 9 | 12 | |||

| 1 unit daily | 2 | 3 | |||

| >1 units daily | 3 | 4 | |||

| Frequency of cannabis consumption | N | % | |||

| Absence | 32 | 43 | |||

| Occasional | 3 | 4 | |||

| 1 intake monthly | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1 intake weekly | 3 | 4 | |||

| 2 intakes weekly | 3 | 3.9 | |||

| 1 intake daily | 8 | 10.5 | |||

| >1 intake daily | 25 | 32.9 | |||

| Patient work situation | Caregiver work situation | ||||

| Working | 29 | 39.2 | Working full-time | 39 | 51.3 |

| Not working | 45 | 60.8 | Working part-time | 7 | 10.0 |

| Not working | 29 | 38.7 | |||

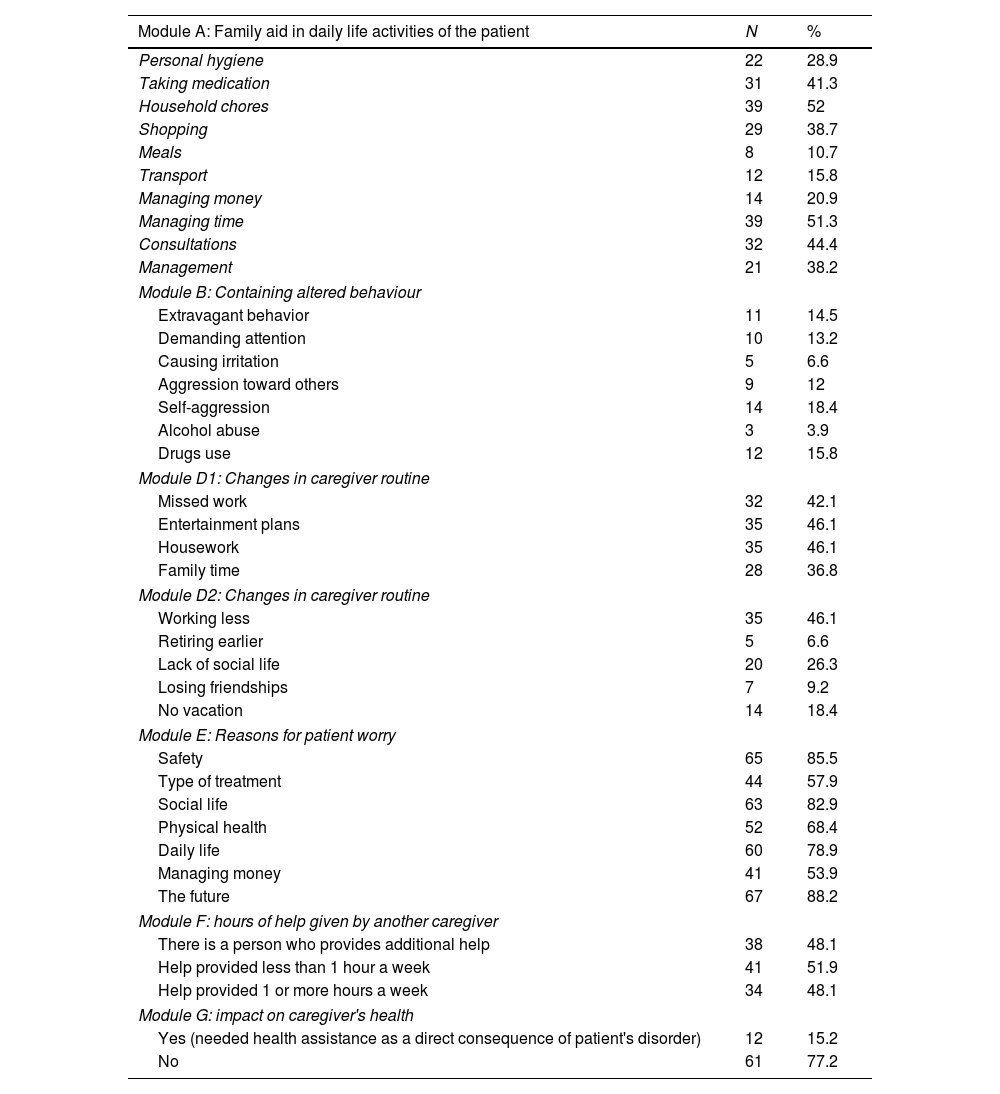

Table 2 presents descriptive data each item of the modules of the ECFOS-II. The largest percentages of caregivers helped the patients in daily activities in managing time (module A), consultations and taking medication. The prevalence of caregivers on containing altered behavior were lower (module B), caregivers supervised patients mostly in self-aggression and substance consumption. Regarding module D, most caregivers modified their lives: working less or missing work, missing entertainment plans, and housework. Most of the caregivers presented great worry about the future, safety, social and daily life of the patients (module E). 38 caregivers (51.4%) had other caregivers helping them; the daily average in hours of care was 4.37.

Description of the presence of each of the items of the ECFOS-II instrument.

| Module A: Family aid in daily life activities of the patient | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Personal hygiene | 22 | 28.9 |

| Taking medication | 31 | 41.3 |

| Household chores | 39 | 52 |

| Shopping | 29 | 38.7 |

| Meals | 8 | 10.7 |

| Transport | 12 | 15.8 |

| Managing money | 14 | 20.9 |

| Managing time | 39 | 51.3 |

| Consultations | 32 | 44.4 |

| Management | 21 | 38.2 |

| Module B: Containing altered behaviour | ||

| Extravagant behavior | 11 | 14.5 |

| Demanding attention | 10 | 13.2 |

| Causing irritation | 5 | 6.6 |

| Aggression toward others | 9 | 12 |

| Self-aggression | 14 | 18.4 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3 | 3.9 |

| Drugs use | 12 | 15.8 |

| Module D1: Changes in caregiver routine | ||

| Missed work | 32 | 42.1 |

| Entertainment plans | 35 | 46.1 |

| Housework | 35 | 46.1 |

| Family time | 28 | 36.8 |

| Module D2: Changes in caregiver routine | ||

| Working less | 35 | 46.1 |

| Retiring earlier | 5 | 6.6 |

| Lack of social life | 20 | 26.3 |

| Losing friendships | 7 | 9.2 |

| No vacation | 14 | 18.4 |

| Module E: Reasons for patient worry | ||

| Safety | 65 | 85.5 |

| Type of treatment | 44 | 57.9 |

| Social life | 63 | 82.9 |

| Physical health | 52 | 68.4 |

| Daily life | 60 | 78.9 |

| Managing money | 41 | 53.9 |

| The future | 67 | 88.2 |

| Module F: hours of help given by another caregiver | ||

| There is a person who provides additional help | 38 | 48.1 |

| Help provided less than 1 hour a week | 41 | 51.9 |

| Help provided 1 or more hours a week | 34 | 48.1 |

| Module G: impact on caregiver's health | ||

| Yes (needed health assistance as a direct consequence of patient's disorder) | 12 | 15.2 |

| No | 61 | 77.2 |

Note: ECFOS-II, Objective and Subjective Family Burden Interview.

First, we controlled for several demographic factors. There were no differences between males and females with FEP in the level of family burden experienced by the caregiver in any of the domains. There were no differences between caregivers working full time compared to those working part-time or not working in any of the domains of the levels of burden experienced. Finally, there were no significant correlations between frequency of consumption of substances of the patients (alcohol, tobacco and cannabis) and the levels of family burdening in any of the domains.

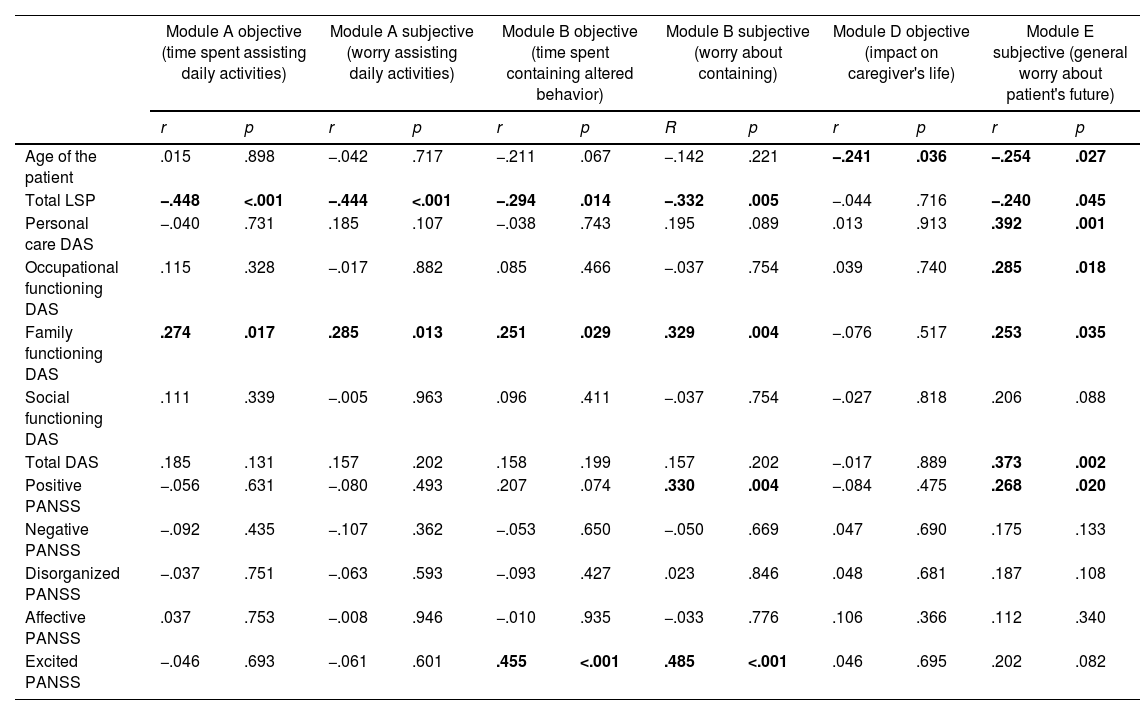

Table 3 shows the correlation between each module of family impact and symptoms and social functioning. Regarding the age of the patient, caregivers of younger individuals reported higher levels of objective burdening (time spent) regarding impact on their own daily lives (module D), and higher levels of subjective burdening in general concerns about the patient (module E).

Correlations among the family burden domains, and sociodemographic and clinical functioning factors of the patient.

| Module A objective (time spent assisting daily activities) | Module A subjective (worry assisting daily activities) | Module B objective (time spent containing altered behavior) | Module B subjective (worry about containing) | Module D objective (impact on caregiver's life) | Module E subjective (general worry about patient's future) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | r | p | R | p | r | p | r | p | |

| Age of the patient | .015 | .898 | −.042 | .717 | −.211 | .067 | −.142 | .221 | −.241 | .036 | −.254 | .027 |

| Total LSP | −.448 | <.001 | −.444 | <.001 | −.294 | .014 | −.332 | .005 | −.044 | .716 | −.240 | .045 |

| Personal care DAS | −.040 | .731 | .185 | .107 | −.038 | .743 | .195 | .089 | .013 | .913 | .392 | .001 |

| Occupational functioning DAS | .115 | .328 | −.017 | .882 | .085 | .466 | −.037 | .754 | .039 | .740 | .285 | .018 |

| Family functioning DAS | .274 | .017 | .285 | .013 | .251 | .029 | .329 | .004 | −.076 | .517 | .253 | .035 |

| Social functioning DAS | .111 | .339 | −.005 | .963 | .096 | .411 | −.037 | .754 | −.027 | .818 | .206 | .088 |

| Total DAS | .185 | .131 | .157 | .202 | .158 | .199 | .157 | .202 | −.017 | .889 | .373 | .002 |

| Positive PANSS | −.056 | .631 | −.080 | .493 | .207 | .074 | .330 | .004 | −.084 | .475 | .268 | .020 |

| Negative PANSS | −.092 | .435 | −.107 | .362 | −.053 | .650 | −.050 | .669 | .047 | .690 | .175 | .133 |

| Disorganized PANSS | −.037 | .751 | −.063 | .593 | −.093 | .427 | .023 | .846 | .048 | .681 | .187 | .108 |

| Affective PANSS | .037 | .753 | −.008 | .946 | −.010 | .935 | −.033 | .776 | .106 | .366 | .112 | .340 |

| Excited PANSS | −.046 | .693 | −.061 | .601 | .455 | <.001 | .485 | <.001 | .046 | .695 | .202 | .082 |

Note: data in bold represent statistical significance at p<0.05

We also controlled for economic factors. The economic incomes of the family did not have any association with any of the domains of family burden. A higher economic income of the patient only associated with less subjective burdening in general concerns (module E) (r=−0.267, p=0.023), so it was included in subsequent analyses.

There was a relationship between the time spent in assisting the patient in daily activities (objective burden of module A) and social functioning measured by the LSP (total score and all the subscales except for responsibility), and disability in family functioning measured by DAS-sv. The subjective score of module A (worry about assisting the patient) was related to socialization, total LSP and disability in family functioning. Time spent on containing altered behavior (module B) was related to social functioning measured by the LSP (total score and all the subscales except for responsibility), excitatory symptoms (PANSS), and disability in family functioning. The subjective module of B (worry) only related to family functioning (DAS) and socialization (LSP). Finally, general worry about global problems of the patient (module E) was related to positive symptoms, and disability (total and all subscales except for social disability).

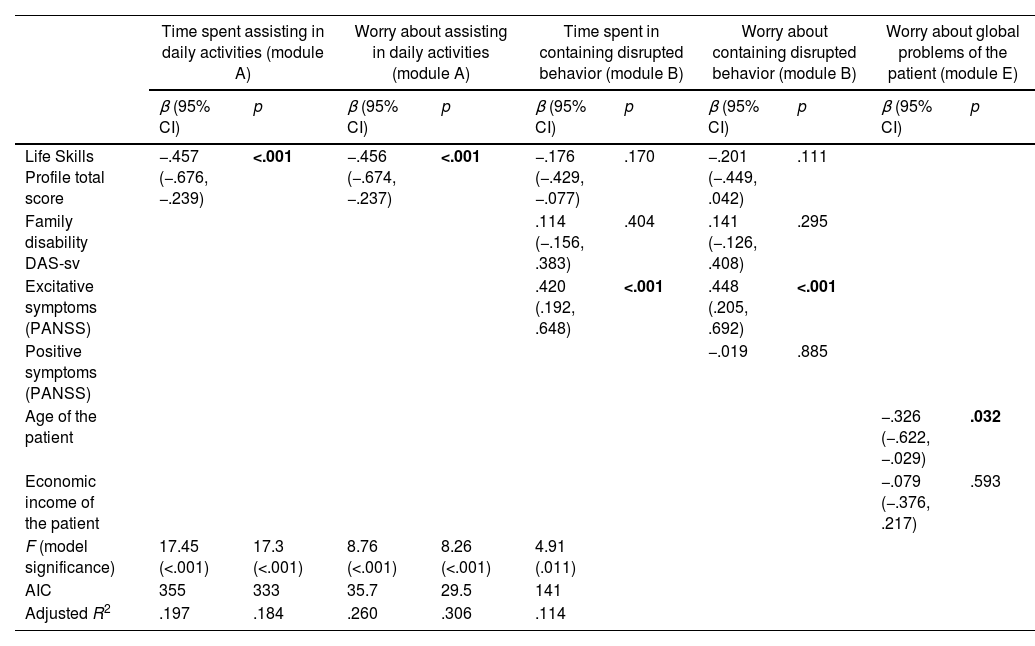

Table 4 shows the hierarchical regression models.

Final hierarchical regression models to explain domains of family burdening.

| Time spent assisting in daily activities (module A) | Worry about assisting in daily activities (module A) | Time spent in containing disrupted behavior (module B) | Worry about containing disrupted behavior (module B) | Worry about global problems of the patient (module E) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | β (95% CI) | p | |

| Life Skills Profile total score | −.457 (−.676, −.239) | <.001 | −.456 (−.674, −.237) | <.001 | −.176 (−.429, −.077) | .170 | −.201 (−.449, .042) | .111 | ||

| Family disability DAS-sv | .114 (−.156, .383) | .404 | .141 (−.126, .408) | .295 | ||||||

| Excitative symptoms (PANSS) | .420 (.192, .648) | <.001 | .448 (.205, .692) | <.001 | ||||||

| Positive symptoms (PANSS) | −.019 | .885 | ||||||||

| Age of the patient | −.326 (−.622, −.029) | .032 | ||||||||

| Economic income of the patient | −.079 (−.376, .217) | .593 | ||||||||

| F (model significance) | 17.45 (<.001) | 17.3 (<.001) | 8.76 (<.001) | 8.26 (<.001) | 4.91 (.011) | |||||

| AIC | 355 | 333 | 35.7 | 29.5 | 141 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | .197 | .184 | .260 | .306 | .114 | |||||

Note: data in bold represent statistical significance at p<0.05

Time spent assisting in daily activities was explained by model 1, by the overall social functioning of the patient (LSP total score). The DAS-sv score of family disability was entered on a second block, but its contribution was not statistically significant (model comparison change in R2=0.00323, p=0.607). The subjective burdening about time spent assisting in daily activities was also best explained by model 1, by the social functioning of the patient (LSP total score). The DAS-sv score of family disability was tested on a second model, but its contribution did not reach significance (model comparison change in R2=0.000878, p=0.789).

Time spent in containing disrupted behavior was finally explained by model 3. LSP total score was significant on step 1 (F=5.89, p=.018), and family disability assessed by DAS-sv was also significant on step 2 (model comparison 1–2 change in R2=0.06, p<.039). However, both variables lost their statistical significance once excitative symptoms were included (model comparison 2–3 change in R2=0.15, p<.001). The subjective burdening of containing disrupted behavior was best explained by excitative symptoms and social functioning in a lesser extent. The social functioning factors lost their statistical significance once excitative symptoms were entered in the third block of the model. The model comparison when adding positive symptoms at step 3 did not reach statistical significance. The model comparison at the final stage reached statistical significance (model comparison 2 to 3, change in R2=0.14, F=13.53, p<.001).

The hierarchical regression model for impact on caregiver's life was not built as it was only explained by the age of the patient.

Finally, the final model for general worry about patient's future was model 1, explained mainly by the age of the patient and with little contribution of economic income of the patient. The DAS-sv total score was removed from the model as it showed signs of multicollinearity (tolerance value of 0.478). The addition of social functioning (LSP total score) showed a trend level of statistical contribution (change in R2=0.049, p=0.066). The addition of positive symptoms in model 3 did not make significant contributions to the model (change in R2=0.032, p=.131).

DiscussionOur study aimed to identify the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of patients with FEP that contribute to the objective and subjective burdening of their informal caregivers. We found distinct clinical and sociodemographic determinants of family burdening.

Higher scores in assisting in daily activities were mainly explained by a lowered social functioning in daily life of the patient. Higher scores in containing disrupted behavior were explained mainly by higher severity of excitative symptoms, but also by lower social functioning and general disability in the family context. More changes in the caregiver's routine were related to younger age of the patient. Finally, a general worry about global problems of the patient was determined by younger age of the patient, and by lower economic incomes in a lesser extent. However, we did not find differential determinants between objective (i.e. Time spent) and subjective (i.e. Experienced worry) components of each family burdening domain.

The impaired social functioning of the patient with FEP was the most consistent determinant of family burdening, in both assisting in daily activities and containing disrupted behavior, which is congruent with previous studies in both high-income countries10,12 and lower-resource countries.23,24 In this sense, more than half of the caregivers reported working less and dedicated more than 28h/week to assist the patient. This implies high direct costs to the family, as caregivers may lose access to professional development and financial repercussions. Therefore, impaired psychosocial functioning of people with FEP not only has a direct impact in health care costs, but also an indirect cost to society by the loss of productivity of the caregiver.25 A younger age of the patient also determined more changes in the caregiver's routine (mainly in working fewer hours) and in worry about general problems of the patient (most often, the perspectives of the patient's future and safety), which may be expected as young people need more family support. This result is congruent with previous literature that finds that two of the major determinants of overburdening in informal caregiving in Western countries are the level of dependency of the patient and having an adult–child relationship.13 In addition, having an early onset of the disorder implies that patients are affected in the developmental period where essential social skills are learned, before finishing school and before the entrance to the labor market, thus contributing to a poorer prognosis compared to later onsets of the disorder.26 Regarding symptomatology, a major finding of this study is that excitative symptoms were more determinant than positive symptoms in explaining burdening when containing altered behavior. This result contrasts with previous studies that found positive symptoms to impact family burdening, both in first-episode and more chronic conditions of the disorder.10 One possible explanation of this finding is that the studies reviewed use the classic division of the PANSS scale, merging positive and excitative symptoms together under the factor of positive symptoms, while in our study we have separated these factors following an empirical-driven division of the PANSS. The patient experiencing hostility, poor impulse control, excitement, and uncooperativeness impacts more on the caregiver than the patient having active delusions and hallucinations that are not accompanied by disrupting behaviors. This is consistent with previous observations that harmful and aggressive behaviors are a major cause of concern among caregivers of patients with FEP, profoundly affecting their wellbeing.27,28

We found small differences among predictors when explaining objective and subjective components of family burdening in FEP. However, when performing the hierarchical regression analysis, only the age of the patient specifically explained worry about general problems of the patient. These findings are different from those of a study done in chronic stages of the disorder.12 One possible interpretation of this difference is the measures of objective burdening. Our study focused on time spent in assisting or containing the patient, for which we found clinical determinants, while the former study focused on economic assistance to the patient and did not find any clinical or social factor of the patient that explained money spent in assisting the patient. Our sample was composed mainly by adolescents up to 17 years old. It is likely that their informal caregivers worry more about the future of the patients because the onset of the disorder has taken place during a sensible period for their social and occupational life and have more dependence from their caregivers.

The findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The cross-sectional design impedes establishing causal conclusions. Longitudinal studies on the follow-up of the impact on the caregivers should be considered to better establish the predictors of family burdening on caring people with FEP. Our assessment of family burdening attempted to be comprehensive using the ECFOS, however we failed to capture more fine-grained aspects of subjective burdening such as the generation of complex emotions of shame, depressive symptoms and anxiety.5 We controlled for economic income of the family and the patient, but future studies should perform more detailed assessments of socioeconomic costs to provide a more complete account of the indirect impacts of the disorder in society. Finally, we found no gender differences between male and female FEP patients in the levels of burdening, and despite we attempted to control the variable of the sex of the patient as a possible influencing factor, our sample size was underpowered to perform separate analyses between males and females with FEP. This would be relevant to perform in future studies with bigger samples in order to provide more gender-sensitive understandings of the disease, following current claims in research in psychiatry.29

Despite limitations and with further replication, our results may have implications for research and clinical practice. Chief among them is that understanding if there are differential determinants of objective and subjective burdening in informal caregivers of FEP patients may be essential to optimize current early support programs and psychoeducational interventions for caregivers. This will help in providing more specialized and effective interventions. Second, study designs may benefit of separating positive and excitative domains of psychotic symptoms when investigating caregiver's burdening. Third, our results support the use of multicomponent and integrated early interventions specialized in recovering from a first-episode psychosis.30–33 These interventions tackle the treatment of a first episode from multiple axes: comprehensive use of antipsychotics, individual psychosocial treatments, family interventions and vocational support, and are associated with a reduction of psychotic symptomatology, improved functioning and decreased family burdening, in this last one where the positive effects are enhanced over time. Our results may suggest that these interventions may contribute to a similar reduction in objective, in terms of time spent, and subjective, in terms of worry, components of family burdening in FEP. Moreover, these services may provide additional support to informal caregivers of early-onset patients, as they may initially experience higher levels of burdening. These ideas should be tested in future studies of family and early interventions services of first episode psychosis. Finally, the onset of the illness may be the most optimal time to intervene with family members, as their worry may act as a motivational motor for being open to help.34

Conflict of interestThe authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Funding for this study was provided by “Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Health (FIS PI05/1115)” and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the “Centro de Investigación en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM)” and “Caja Navarra”; these institutions had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.