Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is characterised by a pattern of negative, defiant, disobedient and hostile behaviour towards authority figures. ODD is one of the most frequent reasons for clinical consultation on mental health during childhood and adolescence. ODD has a high morbidity and dysfunction, and has important implications for the future if not treated early.

ObjectiveTo determine the prevalence of ODD in schoolchildren aged 6–16 years in Castile and Leon (Spain).

Materials and methodsPopulation study with a stratified multistage sample, and a proportional cluster design. Sample analysed: 1049. Cases were defined according to DSM-IV criteria.

ResultsAn overall prevalence rate of 5.6% was found (95% CI: 4.2–7%). Male gender prevalence=6.8%; female=4.3%. Prevalence in secondary education=6.2%; primary education=5.3%. No significant differences by gender, age, grade, type of school, or demographic area were found. ODD prevalence without considering functional impairment, such as is performed in some research, would increase the prevalence to 7.4%. ODD cases have significantly worse academic outcomes (overall academic performance, reading, maths and writing), and worse classroom behaviour (relationship with peers, respect for rules, organisational skills, academic tasks, and disruption of the class).

ConclusionsCastile and Leon has a prevalence rate of ODD slightly higher to that observed in international publications. Depending on the distribution by age, morbidity and clinical dysfunctional impact, an early diagnosis and a preventive intervention are required for health planning.

El trastorno negativista desafiante (TND) se caracteriza por un patrón de comportamiento negativista, desafiante, desobediente y hostil, dirigido a las figuras de autoridad. El TND es uno de los motivos más frecuentes de consulta clínica en salud mental durante la infancia y adolescencia. Presenta gran morbilidad y disfuncionalidad, mostrando repercusiones futuras si no es tratado de forma temprana.

ObjetivoDeterminar la tasa de prevalencia de TND en escolares de 6-16 años de Castilla y León (España).

Material y métodosEstudio epidemiológico poblacional, con diseño muestral polietápico estratificado, proporcional y por conglomerados. Muestra analizada: 1.049 sujetos. Casos definidos según criterios DSM-IV.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de TND es 5,6% (IC 95%: 4,2–7%). Prevalencia género masculino=6,8%; femenino=4,3%. Prevalencia educación secundaria=6,2%; educación primaria=5,3%. No existen diferencias significativas en función del sexo, edad, tipo de centro, ni por zona sociodemográfica. La prevalencia de TND sin considerar deterioro funcional aumentaría al 7,4%. Los casos de TND presentan significativamente peores resultados académicos (resultados académicos globales, lectura, matemáticas y expresión escrita) y peor conducta en clase (relación con compañeros, respeto a las normas, destrezas de organización, realización de tareas académicas e interrupción de la clase).

ConclusionesCastilla y León presenta una tasa de prevalencia de TND levemente superior a la observada en publicaciones internacionales. En función de su distribución por edad, morbilidad y repercusión clínica disfuncional, parece necesaria una planificación sanitaria que incida en un diagnóstico temprano e intervención preventiva.

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), according to DSMIV-TR criteria,1 is characterised by a recurring pattern of negative, defiant, disobedient and hostile behaviour against authority figures. The various types of behaviour should appear with greater frequency than the behaviour typically observed in subjects of similar age and development level, producing significant deterioration of work, educational or social activities.

This disorder is of relevant interest currently and, in children, is a frequent motive for referral to child psychiatrists and clinical psychologists.2–4 The symptoms of ODD usually appear before 8 years of age, present little variability in development and continue from pre-school up until adolescence.5

Various comorbidities are frequently found with ODD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), anxiety disorder, depressive disorder and learning disorder.1,6,7

In this context, several authors have suggested that ODD and ASPD are very much related to each other, considering that the first is a mild form of the second or that it is its precursor. However, recent studies tend to consider that ODD is a separate entity that has different genetic and socio-cultural factors.8

Studies on ODD reflect that it predicts disorders such as depression, anxiety, ADHD and ASPD; it also predicts poor psychosocial adjustment in the form of future criminal actions and more social and family problems.6,7,9,10 Along this same predictive line, longitudinal studies indicate that children with behavioural problems are more likely as adults to commit crimes, abuse drugs, suffer from anxiety or depression, attempt to kill themselves, have multiple sexual partners, display violence and have children prematurely.4

A specific longitudinal study reflected similar predictive variables for ODD and ASPD. These included tobacco use by the mother during pregnancy, exposure to socio-economic adversity, unsuitable paternal behaviour, exposure to abuse and violence between parents, deficient cognitive abilities and association with inappropriate friends during adolescence.9

After reviewing the concept of ODD, comorbidity and dimensions that the disorders predicts or that are predicted by the disorder, we realise that ODD is a disorder that has important clinical relevance and great dysfunctionality.

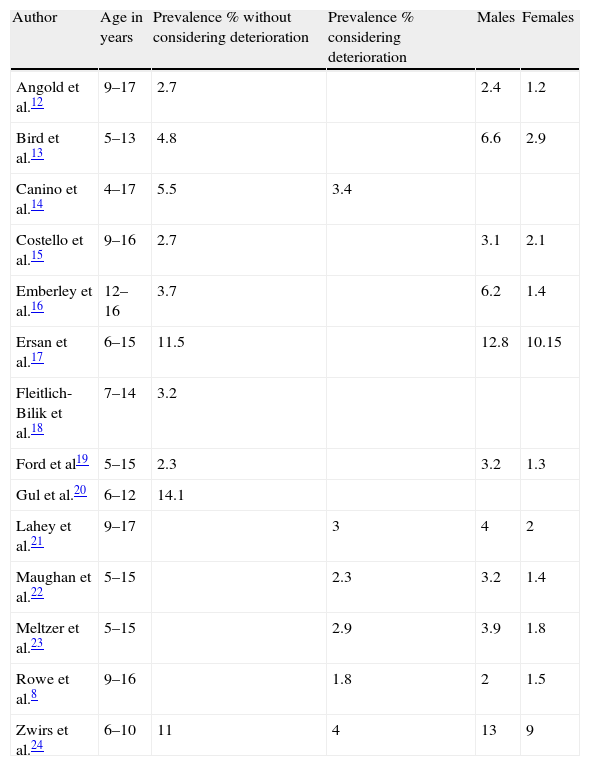

The most referenced prevalence rates for school-age children are 2–16%.1 We note a group of studies whose rates range from 1.8% to 14.1% (Table 1) and have the use of DSM-IV criteria and an age margin that includes the one we utilised in our research as a common element.

Epidemiological studies on oppositional defiant disorder (DSM-IV criteria).

| Author | Age in years | Prevalence % without considering deterioration | Prevalence % considering deterioration | Males | Females |

| Angold et al.12 | 9–17 | 2.7 | 2.4 | 1.2 | |

| Bird et al.13 | 5–13 | 4.8 | 6.6 | 2.9 | |

| Canino et al.14 | 4–17 | 5.5 | 3.4 | ||

| Costello et al.15 | 9–16 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 2.1 | |

| Emberley et al.16 | 12–16 | 3.7 | 6.2 | 1.4 | |

| Ersan et al.17 | 6–15 | 11.5 | 12.8 | 10.15 | |

| Fleitlich-Bilik et al.18 | 7–14 | 3.2 | |||

| Ford et al19 | 5–15 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 1.3 | |

| Gul et al.20 | 6–12 | 14.1 | |||

| Lahey et al.21 | 9–17 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| Maughan et al.22 | 5–15 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 1.4 | |

| Meltzer et al.23 | 5–15 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 1.8 | |

| Rowe et al.8 | 9–16 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Zwirs et al.24 | 6–10 | 11 | 4 | 13 | 9 |

The variability seen in these prevalence rates is influenced by the method of establishing the sample, the clinical and/or psychometric strategy, cut-off point used in the scales, informant or number of informants, age, information source, diagnostic criteria and the inclusion of deterioration in the definition.

Previous studies have found that the estimations of population prevalence for the majority of child disorders vary depending on the presence or absence of social, work or academic dysfunction as diagnostic criteria. Table 1 reflects the fact that when epidemiological studies include deterioration in the definition of ODD, prevalence drops.

One of our goals was to review prevalence studies on the target population. The main objective of our research was to establish the prevalence of ODD in children aged 6–16 years in Castile and Leon, while the secondary objectives were as follows:

- -

Establish the differences between individuals with ODD and those that lack this problem based on socio-demographic variables.

- -

Establish the differences between individuals with ODD and those that lack this problem based on academic results.

- -

Establish the differences between individuals with ODD and those that lack this problem in overall class behaviour.

The relevance of our study lies in the fact that ODD is an important clinical problem in terms of mortality and dysfunctionality in the child–adolescent population and seems to require studies that investigate the specific magnitude of the problem in order to plan institutional health programmes adjusted to the needs observed. Taking dysfunction (an essential criterion from the clinical perspective when dealing with a disorder) into account, there are no prevalence studies on the general population in Spain. Our analysis is an attempt to collaborate in this dimension.

Materials and methodsThe population included students from primary and secondary schools aged between 6 and 16 years from the Castilla y León Community (Spain). The sampling design was multi-stage, stratified and of proportional cluster size. The geographical area included school centres in Valladolid (n=3), Zamora (n=2), León (n=2), Burgos (n=2), Salamanca (n=2), Ávila (n=2), Palencia (n=2) and Segovia (n=1).

Sample size was calculated using the formulation n=N×Zα2p×q/d2(N−1)+Zα2×p×q. Total population was 212,567. A sampling error of 0.05 was considered for an expected prevalence of 6% and a precision of ±1.5. The level of confidence was 95%. With these data, the minimum sample size was 959 students (fraction of sampling %=0.451), extended to 1100 for losses forecast.

InstrumentsThe parents implemented a questionnaire about ODD that included items from the DSM-IV, based on the model included in the Category B of the Child Symptom Inventory (CSI).25 In our study we used a categorical valuation where a symptom is considered clinically relevant if it occurs “often” or “very often” (score=1) and is considered irrelevant if it happens “occasionally” or “never” (score=0). When the number of symptoms is equal to or more than that required by the DSMIV in ODD (≥4), the diagnosis is considered present; if not, it is considered absent. We called this classification categorical ODD (ODD-C).

The reliability of the ODD questionnaire for parents measured using Cronbach's alpha was 0.90, while the test–retest reliability was 0.80. The study of criterion validity presented sensitivity for clinical diagnosis of ODD of 0.79 and specificity of 0.75.

To observe ODD dysfunctionality (DSM-IV clinical criterion), the parents implemented a section of the NICHQ Vanderbilt assessment scale.26

ProcedureWe selected 16 school centres randomly. Using another random selection, we later chose 33 primary units and 20 secondary ones, respecting the proportionality over the type of centre and socio-demographic area.

The field work comprised a phase consisting of gathering socio-demographic data, parent responses to the Category B of ODD included in the CSI and implementation of a section of the NICHQ Vanderbilt assessment scale26 that involved overall academic results and overall behaviour.

The overall academic results included 4 categories valued according to a Likert scale that ranged from 1 to 5 (overall academic results, reading, mathematics and written expression).

The overall behaviour included 5 categories valued according to a Likert scale that ranged from 1 to 5 (relationship with classmates, respect for regulations, organisational skills, performance of academic tasks and class interruptions).

The Likert scale for overall academic results and overall behaviour presented the following categories: much lower than classmates (score of 1), lower than classmates (score of 2), similar to the mean of classmates (score of 3), higher than the mean of classmates (score of 4) and much higher than the mean of classmates (score of 5).

We speak of dysfunction in social or academic activity when there are scores of ≤2 in overall academic results or overall behaviour.

Criterion for inclusion/exclusion of cases:

- •

We considered it a case of ODD when the number of categorical symptoms was equal to or more than that required by the DSMIV (≥4) on the CSI questionnaire (Category B) for parents and when dysfunction was observed in social or academic activity, assessed by at least 1 score of ≤2 in overall behaviour and/or overall academic results. This situation was designated as categorical dysfunctional ODD (ODD-CD).

- •

We did not consider it to be a case of ODD-CD when there was failure to comply with the conditions indicated above.

This project received the backing of the research commission and the ethical committee for clinical trials. The parents of the children included in the study accepted and signed an informed consent document.

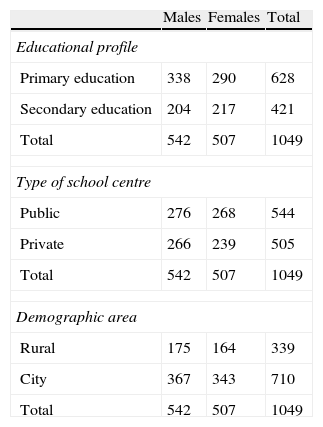

ResultsSocio-demographic dataTable 2 is a summary of the main socio-demographic data from the sample, based on gender.

Socio-demographic sample data.

| Males | Females | Total | |

| Educational profile | |||

| Primary education | 338 | 290 | 628 |

| Secondary education | 204 | 217 | 421 |

| Total | 542 | 507 | 1049 |

| Type of school centre | |||

| Public | 276 | 268 | 544 |

| Private | 266 | 239 | 505 |

| Total | 542 | 507 | 1049 |

| Demographic area | |||

| Rural | 175 | 164 | 339 |

| City | 367 | 343 | 710 |

| Total | 542 | 507 | 1049 |

Mean age of overall sampling was 10.9 years (SD=3.06). By gender, 51.6% were male (mean age=10.77; SD=3.01) and 48.4% were female (mean age, 11.04; SD=3.10).

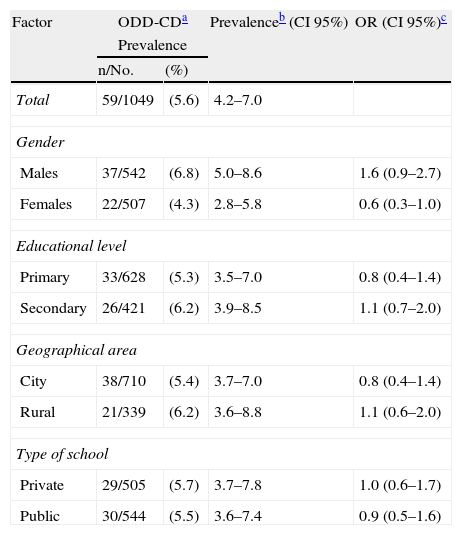

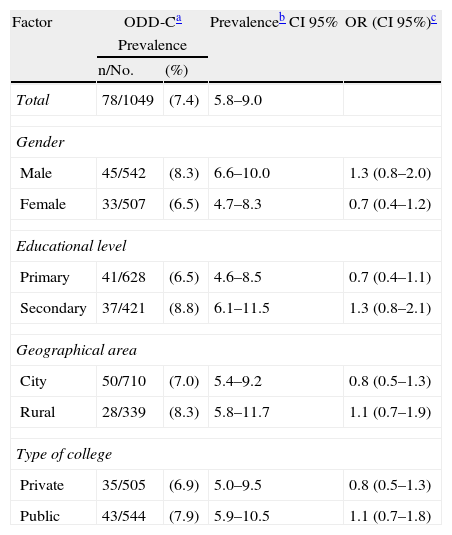

Main basic results: prevalence studyThe set of results on prevalence can be seen in Table 3 (ODD-CD) and 4 (ODD-C). The prevalence of ODD-CD in Castile and Leon is 5.6%, while that of ODD-C rises to 7.4%. This difference is statistically significant [χ(1,n=1049)2=778; P=.000].

Prevalence of categorical–dysfunctional oppositional defiant disorder in Castile and Leon.

| Factor | ODD-CDa | Prevalenceb (CI 95%) | OR (CI 95%)c | |

| Prevalence | ||||

| n/No. | (%) | |||

| Total | 59/1049 | (5.6) | 4.2–7.0 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Males | 37/542 | (6.8) | 5.0–8.6 | 1.6 (0.9–2.7) |

| Females | 22/507 | (4.3) | 2.8–5.8 | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) |

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary | 33/628 | (5.3) | 3.5–7.0 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) |

| Secondary | 26/421 | (6.2) | 3.9–8.5 | 1.1 (0.7–2.0) |

| Geographical area | ||||

| City | 38/710 | (5.4) | 3.7–7.0 | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) |

| Rural | 21/339 | (6.2) | 3.6–8.8 | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) |

| Type of school | ||||

| Private | 29/505 | (5.7) | 3.7–7.8 | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) |

| Public | 30/544 | (5.5) | 3.6–7.4 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) |

The ODD-CD cases present a mean age of 11.41 years (SD=3.11) and include 62.7% males (mean age=11.05; SD=2.97) and 37.3% females (mean age=12; SD=3.32). The cases of ODD-C present a mean age of 11.53 years (SD=3.10) and include 57.7% males (mean age=11; SD=2. 90) and 42.3% females (mean age=12.24; SD=3.26).

Distribution of oppositional defiant disorder/genderPrevalence of ODD-CD (Table 3) and ODD-C (Table 4) is higher for males than for females, without significant differences. Differences in prevalence in favour of males are greater when there is more dysfunction in social or academic activity. The male-to-female ratio ranges between 1.27/1 in ODD-C and 1.58/1 in ODD-CD.

Prevalence of categorical oppositional defiant disorder in Castile and Leon.

| Factor | ODD-Ca | Prevalenceb CI 95% | OR (CI 95%)c | |

| Prevalence | ||||

| n/No. | (%) | |||

| Total | 78/1049 | (7.4) | 5.8–9.0 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 45/542 | (8.3) | 6.6–10.0 | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) |

| Female | 33/507 | (6.5) | 4.7–8.3 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) |

| Educational level | ||||

| Primary | 41/628 | (6.5) | 4.6–8.5 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

| Secondary | 37/421 | (8.8) | 6.1–11.5 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) |

| Geographical area | ||||

| City | 50/710 | (7.0) | 5.4–9.2 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

| Rural | 28/339 | (8.3) | 5.8–11.7 | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) |

| Type of college | ||||

| Private | 35/505 | (6.9) | 5.0–9.5 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) |

| Public | 43/544 | (7.9) | 5.9–10.5 | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

The prevalence of ODD-CD (Table 3) and ODD-C (Table 4) in primary education is lower than that observed in secondary education, without significant differences. Analysing the ODD-CD cases did not reveal significant differences based on gender between the 2 blocks of primary and secondary education. As in previous analyses, there are always more cases of males, in a ratio of 2/1 in primary education and 1.36/1 in secondary.

Distribution of oppositional defiant disorder/socio-demographic areaThe prevalence of ODD-CD (Table 3) and ODD-C (Table 4) in city areas is lower than that in rural areas. No significant differences were seen.

Analysing the ODD-CD cases did not reveal significant gender-based differences in the different socio-demographic areas. As in previous analyses, there were always more cases of males, with a ratio of 2/1 in the rural areas and 1.53/1 in cities.

Distribution of oppositional defiant disorder/school typeThe prevalence of ODD-CD (Table 3) in private schools is similar to that seen in public schools. In ODD-C (Table 4), higher prevalence is seen in public schools than in private. No significant differences are seen in either situation.

Analysing the ODD-CD cases revealed significant gender-based differences depending on the type of school [χ(1,n=59)2=4.218; P=.04]. There were more males, in a ratio of 3.14/1 in private schools, while there were no differences in public schools (ratio of 1/1).

Distribution of oppositional defiant disorder/academic results and overall behaviourUsing the Vanderbilt assessment scale revealed significant differences in average ranges (Mann–Whitney U test). The cases of ODD-CD, compared with subjects who did not have this condition, had worse overall academic results (U=14.042; P=.000) and lower results in reading (U=16.571; P=.000), maths (U=15.460; P=.000) and written expression (U=15.872; P=.000).

The same questionnaire reflected that ODD-CD cases had worse overall class behaviour (U=8.489; P=.000), poorer relationships with classmates (U=15.189; P=.000), less respect for rules and regulations (U=11.096; P=.000), greater class interruptions (U=18.263; P=.000), poorer organisation abilities (U=15.279; P=.000) and more problematic behaviour involving doing homework (U=12.889; P=.000). Significant differences were seen with the same tendency in ODD-C cases.

DiscussionPrevalence of ODD-CD in Castile and Leon (Spain) is 5.6%. If we consider only the categorical criteria of the DSM-IV (ODD-C), this figure rises to 7.4%. Our results reflect the fact that considering the existence of dysfunction as an epidemiological criterion for ODD reduces prevalence, being compatible with the true magnitude of the problem and with clinical criteria.

The prevalence rates most often cited for school-age children range between 2% and 16%.1 Likewise, the group of studies that we considered in the introduction (for adjusting to DSM-IV criteria and having an age margin that includes the one used in our study) presents figures between 1.8% and 14.1%. The studies mentioned observe that including dysfunctionality reduces prevalence to a margin of 1.8–4%. Our results are slightly above this band of reference.

The prevalence of ODD-CD in our study for males is higher than that for females. This difference is not significant (P=.081) and is greater when there is more dysfunctionality. The literature generally tends to consider a higher frequency for males in ODD in prevalence studies and in the clinical context.2,4,16,27 Among these references, we find a few in which, although greater frequency of ODD is seen for males, differences based on gender are not significant.11,17,21,22

With respect to the factor of age, the prevalence rate in our study for ODD-CD in primary education is lower than that observed in secondary education, with no significant differences. There is a non-significant increase in ODD-CD, perhaps compatible with the DSM reference of increased ODD symptoms with age. Our data are not compatible with a few reviews that indicated that ODD rate decreases in adolescence.28

According to our study, ODD tends not to decrease spontaneously with age. This influences the need for early preventative interventions that reduce the repercussion of ODD with respect to morbidity and dysfunctionality. The evidence tends to show that an important part of mental health disorders have their onset in childhood and adolescence, as well as that prompt attention in the early stages of life can prevent its consequences.29

If we consider the educational cycles, there are no significant differences based on gender in cases of ODD-CD with our data. However, greater frequency of males is observed in both educational cycles, especially in primary education. This is in agreement with studies that indicate lesser gender differences in adolescence.30

Cases of ODD-CD, compared with those that lack this condition, have significantly worse overall academic results and lower results in reading, maths and written expression. This is compatible with its frequent comorbidity in learning disorders.1,6,7 It also agrees with the DSM-IV requirement of presenting significant deterioration in social or academic activity. Despite this requirement, it is also certain that we can diagnose ODD without the presence of deterioration in academic activity and it seems that this school repercussion occurs more often than it does in the control population. Whether this is a cause or a consequence of ODD, it seems necessary to show a preventative attitude towards this school situation.

We note that, in clinical populations, low school performance tends to be associated with behaviour disorders; furthermore, various studies show a link between symptoms of ODD and academic problems.2,31

The cases of ODD-CD have significantly worse overall behaviour in class. Also observed are worse relationships with classmates, less respect for rules and regulations, greater class interruptions, lower organisation skills and more problematic behaviour with respect to doing homework. This set of results seems compatible with ODD, although its diagnosis is possible without the concurrence of all of them. In these circumstances, we feel that a preventative attitude is important regarding the relationships with their peer group and maladaptive behaviours in the school setting.

Insofar as the limitations of our study, we feel that it would have been of interest to have a structured clinical interview with the cases to have greater precision in the diagnosis of ODD and to assess comorbidity.

In summary, ODD in the Castilla y León Community presents a prevalence that lies slightly above normal limits when DSM-IV criteria are used in international samples, reflecting significant impact on academic performance and school behaviour. In parallel to our analysis, longitudinal studies have demonstrated that a considerable number of children that show early symptoms of antisocial behaviour (ODD at the age of 3 years is the second highest figure of prevalence in the general Spanish population32) continue in adolescence/adult stages to experience important mental health, physical health, academic and economic problems and to participate in acts of violence.33,34 Based on the relevance of ODD in terms of morbidity and dysfunctional clinical impact, we should be vigilant for its early diagnosis, preventative intervention and/or treatment of the disorder by scientifically validated procedures. Treatment will require mental health professionals specialised in childhood and adolescence, who should be appropriately trained in dealing with this vital period and integrated in coordinated, multidisciplinary work.29

Providing early treatment designed to reduce the symptoms of ODD should be a priority for those who plan public health, given that even a small reduction in the long-term consequences of these problems would be of great benefit for the individual, the family and society. It is relevant to remember that the load of illness in adolescents and young people in Spain is fundamentally attributable to mental and neurological diseases.35 Consequently, it is essential to reduce the weight of mental health problems in the present and in future generations, in order to favour adequate development in the children who are the most vulnerable.36

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on human beings or animals in this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they followed their work centre protocols on patient data publication and that all of the patients included in the study received sufficient information and gave their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects mentioned in this article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: López-Villalobos JA, Andrés-De Llano JM, Rodríguez-Molinero L, Garrido-Redondo M, Sacristán-Martín AM, Martínez-Rivera MT, et al. Prevalencia del trastorno negativista desafiante en España. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2014;7:80–87.