Background and Aims. The epidemiology of liver cirrhosis differs across sex, ethnic groups, and geographic regions. In 2000, chronic liver disease was the fifth leading cause of death in Mexico. Accurate knowledge of the demographics of liver disease is essential in formulating health-care policies. Our main aim was to project the trends in liver disease prevalence in Mexico from 2005 to 2050 based on mortality data. Methods. Data on national mortality reported for the year 2002 in Mexico were analyzed. Specific-cause mortality rates were calculated for a selected age population (≥25 years old) and classified by sex and projected year (2005–2050). The following codes of the International Classification of Diseases for liver diseases were included: non-alcoholic chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, alcoholic liver disease, liver cancer, and acute and chronic hepatitis B and C infection. The projected prevalence of a chronic liver disease was estimated using the following equation: P = (ID × T) / [(ID × T) + 1], where P = prevalence, ID = incidence density (mortality rate multiplied by 2), T = median survival with the disease (= 20 years). Results: Nearly two million cases of chronic liver disease are expected. Alcohol-related liver diseases remain the most important causes of chronic liver disease, accounting for 996,255 cases in 2050. An emergent syndrome is non-alcoholic liver disease, which will be more important that infectious liver diseases (823,366 vs 46,992 expected cases, respectively). Hepatocellular carcinoma will be the third leading cause of liver disease. Conclusions: Chronic liver disease will be an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the future. Preventive strategies are necessary, particularly those related to obesity and alcohol consumption, to avoid catastrophic consequences.

The authors want to dedicated this article to Dr. Ricardo Sosa-Sanchez for his 60 Birthday.

IntroductionThe epidemiology of liver cirrhosis is characterized by marked differences across sex, ethnic groups, and geographic regions. The nature, frequency, and time of acquisition of the major risk factors for cirrhosis (hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and alcoholic liver disease) may explain these variations.1

Hepatitis C virus infection is one of the leading causes of end-stage liver disease requiring liver transplantation. Major centers report that nearly 25%–30% of their candidate pools consist of hepatitis C virus-infected patients.2 About four million Americans are presently infected with the virus, and 20%–30% of these patients can be expected to progress to cirrhosis.3 Donor availability is the most significant limiting factor for organ transplantation, and leads to the use of less than perfect organs.

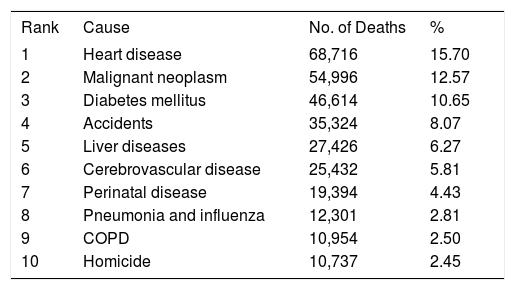

In 2000, chronic liver disease was the fifth leading cause of death in Mexico (Table I). More importantly, it was the second leading cause of death in people aged between 35 and 55 years.4 In Mexico, no study has yet examined the long-term data for future trends in the prevalence of chronic liver disease. We believe that this is important because accurate knowledge of the demographics of liver disease is essential in formulating health-care policies to prioritize health interventions and research and to allocate resources accordingly. Currently in our country, some liver diseases (e.g., non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C) have a high, albeit non-quantified, incidence in the population, and others (e.g., hepatocellular carcinoma or fulminant hepatic failure) are highly lethal. Although effective treatments and preventive therapies are available for many types of liver disease, the long-term consequences of ongoing liver damage may require liver transplantation, one of the most involved medical undertakings performed today.

The ten leading causes of deaths in Mexico (2000) [ref. 4].

| Rank | Cause | No. of Deaths | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heart disease | 68,716 | 15.70 |

| 2 | Malignant neoplasm | 54,996 | 12.57 |

| 3 | Diabetes mellitus | 46,614 | 10.65 |

| 4 | Accidents | 35,324 | 8.07 |

| 5 | Liver diseases | 27,426 | 6.27 |

| 6 | Cerebrovascular disease | 25,432 | 5.81 |

| 7 | Perinatal disease | 19,394 | 4.43 |

| 8 | Pneumonia and influenza | 12,301 | 2.81 |

| 9 | COPD | 10,954 | 2.50 |

| 10 | Homicide | 10,737 | 2.45 |

COPD=Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

An epidemiological transition in chronic liver diseases is apparent in Mexico. Therefore, the main aim of this study was to project the trends in the prevalence of liver diseases in Mexico from 2005 to 2050 based on mortality data.

MethodsExperimental proceduresData on national mortality (death certificates) reported for the year 2002 by the Health Ministry of Mexico were analyzed (www.salud.gob.mx). Specific-cause mortality rates were calculated for a selected age population (≥ 25 years old) and classified by sex for the projected Mexican population (2000–2050) (Consejo Nacional de Población: www.conapo.gob.mx).

Causes of death related to chronic liver diseases were selected in accordance with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. The following codes for liver diseases were included: non-alcoholic chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (K74.0–K74.6), alcoholic liver disease (K70.0– K70.9), liver cancer (C22.0, C22.7, C22.9), acute and chronic hepatitis B (B16.2, B16.9, B18.0, B18.1), and acute and chronic hepatitis C (B17.1, B18.2). To estimate the prevalence of chronic liver disease, the following hypothetical assumptions were made: (a) that the incidence density (ID) of liver disease is at least twice the mortality rate for the selected causes of death, and (b) that the median survival (T) of a person ≥ 25 years of age with chronic liver disease is 20 years. These terms were substituted in the following equation: P = (ID × T) / [(ID × T) + 1],5 where P = prevalence, ID = incidence density (mortality rate multiplied by 2), T = median survival with the disease (= 20 years). Thus, for each chronic liver disease considered, the prevalence (in terms of absolute number of cases) is reported by sex and projected year (from 2005 to 2050).

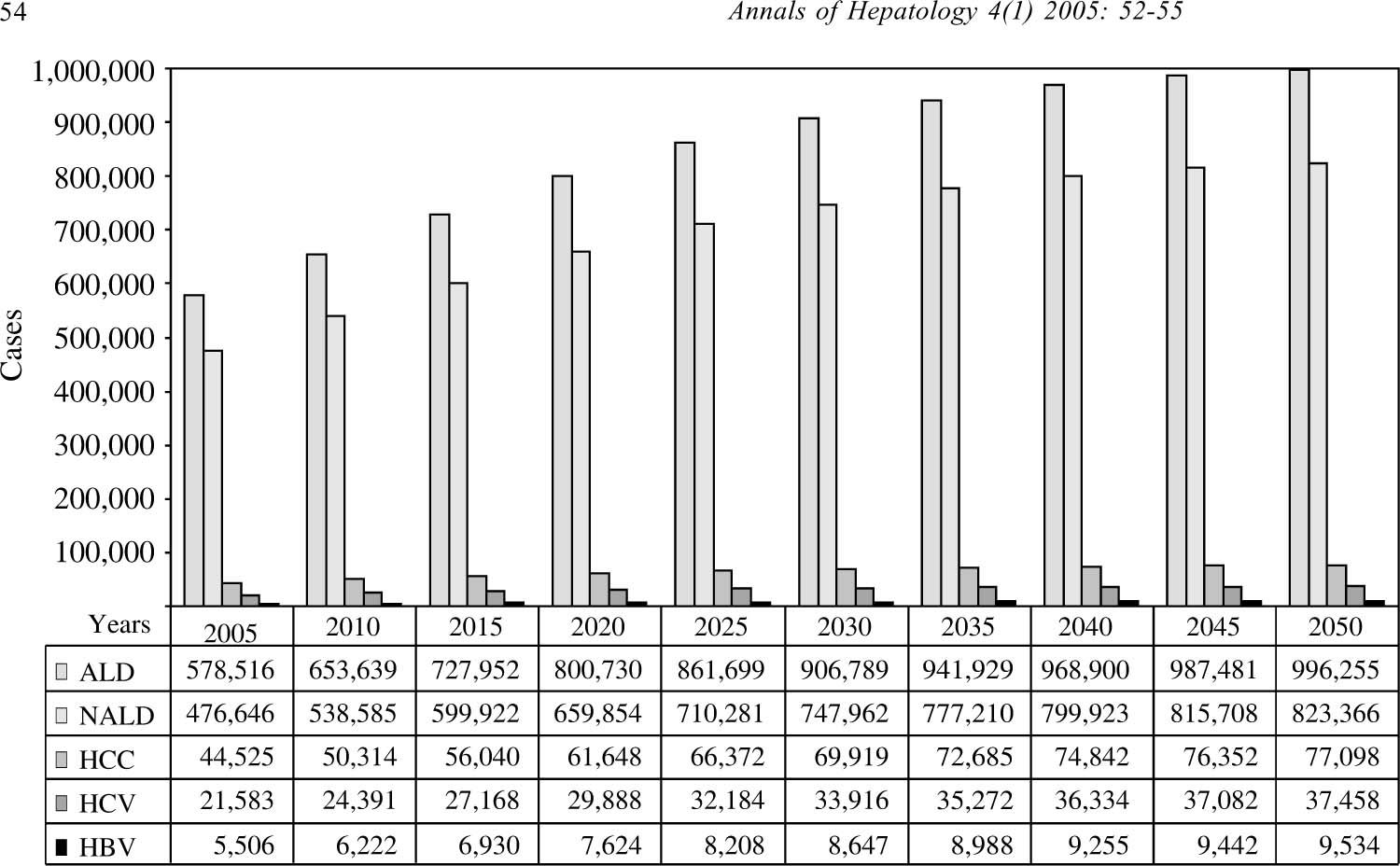

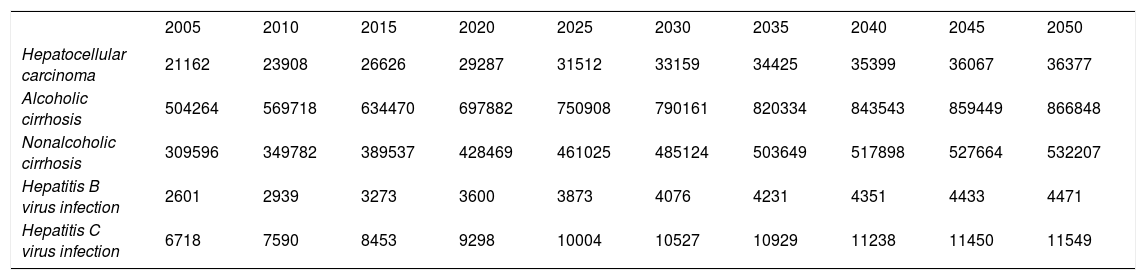

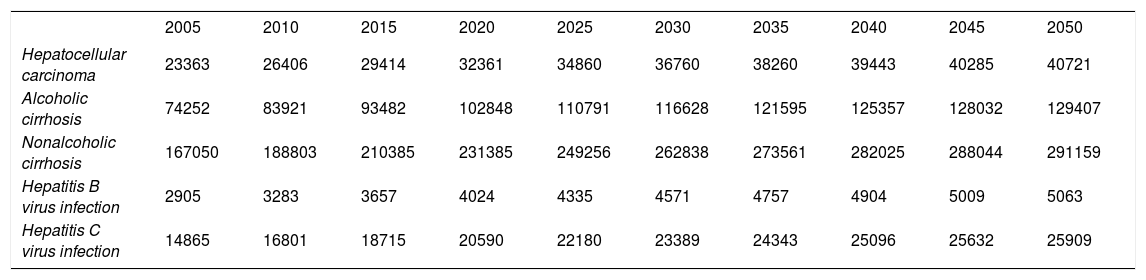

ResultsAnalysis of trends showed an important increase in the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease as the most important cause of hepatic disease in men (Table II). Nearly one million cases of liver disease related to this cause are expected in the general population towards 2050. However, in contrast to the male population, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease will be the most prevalent liver disease in women (Table III), followed by alcoholic liver disease. Importantly, infectious liver diseases constitute a minority in our predicted trends, representing less than 2% of all liver diseases in men and ~6% of all expected cases in women. The first and second most common etiologies of hepatic disease across both sexes (alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease) represent 1,819,621 predicted cases in 2050. Hepatocellular carcinoma will continue as the third leading cause of liver disease, contributing 77,098 cases in the final part of the period evaluated (Figure 1)

Trends in the prevalence of chronic liver diseases in Mexico (men).

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 21162 | 23908 | 26626 | 29287 | 31512 | 33159 | 34425 | 35399 | 36067 | 36377 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 504264 | 569718 | 634470 | 697882 | 750908 | 790161 | 820334 | 843543 | 859449 | 866848 |

| Nonalcoholic cirrhosis | 309596 | 349782 | 389537 | 428469 | 461025 | 485124 | 503649 | 517898 | 527664 | 532207 |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | 2601 | 2939 | 3273 | 3600 | 3873 | 4076 | 4231 | 4351 | 4433 | 4471 |

| Hepatitis C virus infection | 6718 | 7590 | 8453 | 9298 | 10004 | 10527 | 10929 | 11238 | 11450 | 11549 |

Trends in the prevalence of chronic liver diseases in Mexico (women).

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 23363 | 26406 | 29414 | 32361 | 34860 | 36760 | 38260 | 39443 | 40285 | 40721 |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 74252 | 83921 | 93482 | 102848 | 110791 | 116628 | 121595 | 125357 | 128032 | 129407 |

| Nonalcoholic cirrhosis | 167050 | 188803 | 210385 | 231385 | 249256 | 262838 | 273561 | 282025 | 288044 | 291159 |

| Hepatitis B virus infection | 2905 | 3283 | 3657 | 4024 | 4335 | 4571 | 4757 | 4904 | 5009 | 5063 |

| Hepatitis C virus infection | 14865 | 16801 | 18715 | 20590 | 22180 | 23389 | 24343 | 25096 | 25632 | 25909 |

We calculated that both alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver diseases will continue to be the most important liver diseases, accounting for nearly 90% of cases in Mexico in 2050. In a previous issue of Annals of Hepatology, a collaborative study from the Mexican Association of Hepatology showed the etiology of cirrhosis in Mexico.5 As in the 1970s,6-9 alcohol-related cirrhosis remains one of the most important causes of liver disease. Similar data have been reported for other populations. In 1986, 50% of deaths due to cirrhosis in the United States were attributed to alcohol, but in 1997, 40% of deaths from cirrhosis were due to alcohol consumption, with a high economic impact of $600 million to $1.8 billion annually.10 It is important to emphasize that, among men, the mortality rate was highest for Hispanics.11 In a previous study of the Mexican population,12 geographic situation and pattern of consumption were factors related to the mortality associated with alcoholic liver disease. In the Mexican population, subjects with fewer years of education and lower incomes have the highest rates of alcohol consumption.13 Total alcohol consumption in the Mexican population is nine liters per person per year, with a higher prevalence of male drinkers.11 Currently, alcohol is the most common cause of liver cirrhosis. We must emphasize the importance of these observations in any further analysis of other variables associated with increased liver damage and worsening prognoses, particularly factors such as sex, body weight, body mass index, the type and pattern of alcoholic beverage consumed, habitual use of hard liquors, consumption of alcohol without food, and the duration of drinking.14

The importance of nutritional issues in terms of liver disease was first suggested more than 50 years ago.15 Currently, it is clear that nutritional imbalance can significantly affect the development of liver diseases.16 Recently, we analyzed data from the National Survey of Chronic Diseases (ENEC 1993) and the Mexican National Health Survey (ENSA 2000) and observed that the increase in mortality related to liver diseases (particularly cirrhosis) is associated with an increase in the prevalence of overweight patients and obesity.17 In the present study, we observed an emerging new etiology of cirrhosis, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). According to the information we have presented here, NAFLD will be the second most important cause of liver disease in the future, with a higher impact than that of infectious diseases. Furthermore, the Mexican population has a high incidence of overweight members and obesity,18 and Mexicans are prone to developing the insulin resistance associated with obesity (the phenotype known as “metabolic syndrome”).19 It has been suggested that insulin resistance is involved in the pathogenesis of NALFD. In Mexico, type 2 diabetes mellitus is the first and second cause of death in women and men, respectively, and the prevalence of NALFD in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus may be as high as 100%.21 Interestingly, a recent study conducted in the United Sates showed that the Hispanic population has a higher incidence of NAFLD than other populations (45% in Hispanics; 33% in whites; 24% in blacks).22 The pathogenesis of obesity does not just involve racial factors; social, economic, and cultural variables are important issues,23 particularly among Mexican children,24,25 in whom insulin resistance is a risk factor for developing type 2 diabetes mellitus26 and consequent liver disease.

Another problem associated with the predicted high prevalence of chronic liver disease involves the diagnosis of NAFLD. At this time, liver biopsy is the gold standard for this diagnosis. However, a large proportion of subjects with NAFLD are asymptomatic. Therefore, it will be important to develop or improve the tools required for an adequate diagnostic approach.27 We believe that non-invasive diagnostic procedures for NAFLD will be important in preventing chronic liver disease.

Although the rates of infectious liver diseases will become high, patients with hepatitis C virus or hepatitis B virus infections will be numerically less important than those with NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease. However, obesity and alcohol consumption affect the natural histories of chronic hepatitis infections for viruses B and C and their responses to medical treatment.28-31 More studies are required to establish the real incidence of hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus infections, because data about their prevalence in the Mexican population are contradictory.

Considering that nearly two million cases of chronic liver disease are expected in the next 50 years, liver transplantation policies must respond to this demand. However, the high costs associated with this therapeutic modality (US$100,000 per patient per year) necessitate the development of efficient preventive measures to circumvent this catastrophic scenario.10

Hepatocellular carcinoma will be an important topic in the future, because it is currently fifth in the classification of all malignancies and because Latin American countries are among the areas of highest incidence.32 As a consequence of previously described liver diseases, the identification of risk factors and the adequate treatment of infectious liver diseases are urgently needed. However, obesity is a silent disease and has recently been related to a high risk of developing carcinoma.30,33,34 Therefore, modification of lifestyle behavior is an important pathway in preventing one of the most important causes of malignancy.

In conclusion, chronic liver disease will be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the near future. It will be necessary to implement preventive measures, particularly those related to obesity and alcohol consumption, to avoid catastrophic consequences.