To determine the communicative profiles of family physicians and the characteristics associated with an improved level of communication with the patient.

DesignA descriptive multicentre study.

LocationPrimary Healthcare Centres in Almeria, Granada, Jaen and Huelva.

Participants119 family physicians (tutors and 4th year resident physicians) filmed and observed with patients.

Principal measurements: Demographic and professional characteristics. Analysis of the communication between physicians and patients, using a CICAA (Connect, Identify, Understand, Agree and Assist, in English) scale. A descriptive, bivariate, multiple linear regression analysis was performed.

ResultsThere were 436 valid interviews. Almost 100% of physicians were polite and friendly, facilitating a dialogue with the patient and allowing them to express their doubts. However, few physicians attempted to explore the state of mind of the patient, or enquire about their family situation or any important stressful events, nor did they ask open questions. Furthermore, few physicians summarised the information gathered. The mean score was 21.43±5.91 points (maximum 58). There were no differences in the total score between gender, city, or type of centre. The linear regression verified that the highest scores were obtained from tutors (B: 2.98), from the duration of the consultations (B: 0.63), and from the age of the professionals (B: −0.1).

ConclusionPhysicians excel in terms of creating a friendly environment, possessing good listening skills, and providing the patient with information. However the ability to empathise, exploring the psychosocial sphere, carrying out shared decision-making, and asking open questions must be improved. Being a tutor, devoting more time to consultations, and being younger, results in a significant improvement in communication with the patient.

Conocer el perfil comunicacional de los médicos de familia y las caracteristicas asociadas a una mejor comunicación con el paciente.

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo multicéntrico.

EmplazamientoCentros de salud de atención primaria de Almería, Granada, Jaén y Huelva.

ParticipantesCiento diecinueve médicos de familia (tutores y residentes de 4.° año) videograbados en consulta.

Mediciones principalesCaracterísticas demográficas y profesionales. Análisis de la comunicación médico-paciente mediante la escala Conectar, Identificar y Comprender, Acordar y Ayudar (CICAA). Se realizó un análisis descriptivo, bivariable y de regresión lineal múltiple.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 436 entrevistas válidas. Casi el 100% se muestran corteses y amables, facilitan el discurso del paciente y permiten que exprese sus dudas. En cambio, pocos profesionales resumen la información, exploran el estado de ánimo del paciente, su entorno familiar, acontecimientos vitales estresantes o emplean preguntas abiertas. La puntuación media fue de 21.43±5.91 puntos (máximo 58). No existieron diferencias en la puntuación por sexo, ciudad o tipo de centro. Mediante regresión lineal múltiple se comprueba que una mayor puntuación se relaciona con ser tutor (B:2.98), el tiempo de consulta (B:0.63) y la edad del profesional (B: −0,1).

ConclusionesLos médicos destacan por crear un clima cálido, buena escucha e informar al paciente; en cambio, deberían mejorarse la empatía, la exploración de la esfera psicosocial, realizar preguntas abiertas y la toma de decisiones compartidas. Ser tutor, mayor tiempo de consulta y ser más joven se relacionan con una mejor comunicación con el paciente.

Communication is one of the most important skills that a family physician must possess,1,2 as the preceptor is the crux of the process and is jointly responsible, alongside with the resident physician, for adopting and acquiring the appropriate attitude, knowledge and necessary skills.3

The scarce references related to communication skills in our country reflect the fact that the profiles are very centred around the physician's agenda, so a scarce exploration has been carried out of the emotions of the patient, his/her state of mind or repercussions of the problem.4–7

International studies frequently use standardised patients,8,9 which allow the possibility to compare communicational profiles with a high rate of reliability and validity, just like carrying out a summative evaluation.10 However, these types of patients could demonstrate a more accurate vision of the patient–physician relationship, avoiding the peculiarities of the chronic processes and the relationship maintained over time (fundamental in primary care).11

The main objective of the study is to understand the communicational profile of preceptors and of fourth year resident physicians of family medicine. Secondary aims include analyzing the relationship between the communicational and professional profiles of physicians; and the factors associated with improving communication with patients.

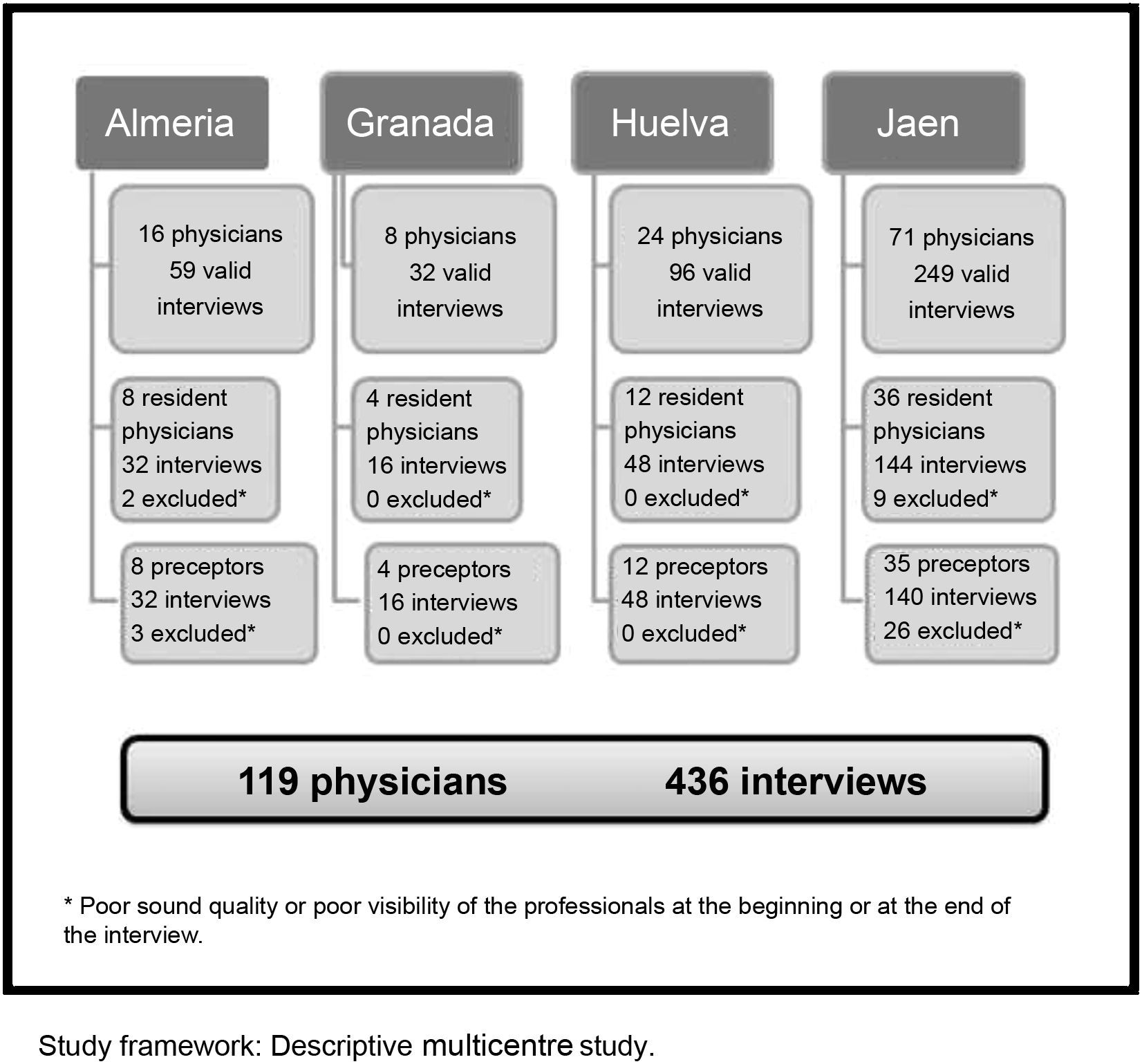

MethodsDesign, location and populationAn observational and descriptive study was carried out in four provinces of Andalusia (Almeria, Granada, Huelva and Jaen), in February 2011 and May 2012.

The target population was family physicians of Andalusia; qualified preceptors and resident 4th year physicians.

The sample size needed was calculated for an accuracy of 1.5 points with an standard deviation of 7.2 in the final score of the CICAA survey12 (level of reliability 95%). Using the Epidat computer programme, the necessary number of physicians was 89, increased by 20% due to possible losses (107 in total). 119 professionals participated voluntarily, carrying out 436 valid videorecordings.

VariablesThe main dependent variable was the score obtained in the CICAA survey13 (following the instructions of the user manual),14 which measures communication and establishes the interviewer's communication profile. It is composed of 29 items structured as a Likert-type scale with three grades: 0 points (unability to carry out the scheduled tasks), 1 point (ability to carry out the scheduled tasks sufficiently) and 2 points (ability to completely or almost completely carry out all the scheduled tasks). The items are grouped into tasks:

- •

Task 1. Communicate well with the patient/family (items 1–6)

- •

Task 2. Identify and understand the patient's/family's healthcare problems (items 7–20)

- •

Tasks 3 and 4. Reach an agreement with the patient/family surrounding the problem/s, possible solutions and actions, and help the patient/family to understand and decide how to deal with the issues (items 21–29).

The total score was calculated along with the successful or non successful completion of each item. It was considered non successful when the item scored 0.

Independent variables included; personal and professional characteristics of physicians (age, gender, marital status and health centre), characteristics of their patients (rural or urban environment, population was higher or lower than 10,000, number of assigned patients, number of assigned patients over 65 years of age, patient load and time dedicated to each patient) and characteristics of single consultations (patient's gender, accompanied by someone, type of problem, first visit and number of reasons they had/motives for needing a medical consultation).

The time allowed for the interview was divided into intervals; exploratory phase (from the beginning of the interview until the physical examination), time spent on the physical examination and resolution phase (from the end of the physical examination until the end of the interview).

Data collectionThe physicians recorded themselves independently during their standard working day. The main researcher selected randomly 4 video recordings of each professional (excluding their first consultation and bureaucratic or internal consultations), which were subsequently analysed by two people alien to the research and trained in the use and management of videorecordings using the CICAA survey.14

The research protocol was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of Jaen Hospital. Informed consent from healthcare professionals and patients was obtained through written or verbal means as demonstrated in the videorecordings. The confidentiality of the information was guaranteed.

Data analysisDescriptive and bivariate analysis were carried out, using Chi-square test, Student's t-test and ANOVA.

Characteristics associated with an improved level of communication were identified with a multiple linear regression analysis, with the total score on the scale as dependent variable. The variables were selected in two models, one backwards and other forwards, with p values of entry and exit of 0.05 and 0.1 respectively. A saturated model was built with the variables included in both models, and a heuristic approach was applied to retain in the final model those variables which changed the coefficient of the main explicative variable (type of professional) in more than 10%.

The intra-observer agreement was verified through the analysis of 40 video recordings with a 2 month interval using an Intraclass Correlation Coefficient. Their values were 0.89 (IC95%: 0.79–0.94) for the first observer and 0.91 (IC95%: 0.84–0.95) for the second one. The inter-observer agreement was 0.94 (IC95%: 0.89–0.96).

The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS (15.0) programme. The significance level was established in p≤0.05.

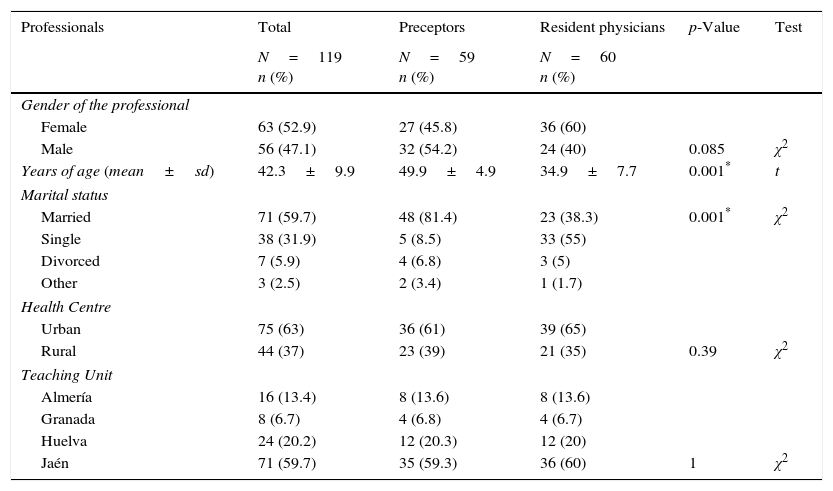

ResultsThe characteristics of professionals and interviews carried out can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. The mean number of assigned patients by physician was 1539.1 (SD: 128.9), and the mean number of patients over 65 years was 239.7 (SD: 57.6). They visit a mean of 41.5 patients by day (SD: 4.1), and the mean time dedicate for patient was 5.6min (SD: 0.7).

Characteristics of professionals.

| Professionals | Total | Preceptors | Resident physicians | p-Value | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=119 n (%) | N=59 n (%) | N=60 n (%) | |||

| Gender of the professional | |||||

| Female | 63 (52.9) | 27 (45.8) | 36 (60) | ||

| Male | 56 (47.1) | 32 (54.2) | 24 (40) | 0.085 | χ2 |

| Years of age (mean±sd) | 42.3±9.9 | 49.9±4.9 | 34.9±7.7 | 0.001* | t |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 71 (59.7) | 48 (81.4) | 23 (38.3) | 0.001* | χ2 |

| Single | 38 (31.9) | 5 (8.5) | 33 (55) | ||

| Divorced | 7 (5.9) | 4 (6.8) | 3 (5) | ||

| Other | 3 (2.5) | 2 (3.4) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Health Centre | |||||

| Urban | 75 (63) | 36 (61) | 39 (65) | ||

| Rural | 44 (37) | 23 (39) | 21 (35) | 0.39 | χ2 |

| Teaching Unit | |||||

| Almería | 16 (13.4) | 8 (13.6) | 8 (13.6) | ||

| Granada | 8 (6.7) | 4 (6.8) | 4 (6.7) | ||

| Huelva | 24 (20.2) | 12 (20.3) | 12 (20) | ||

| Jaén | 71 (59.7) | 35 (59.3) | 36 (60) | 1 | χ2 |

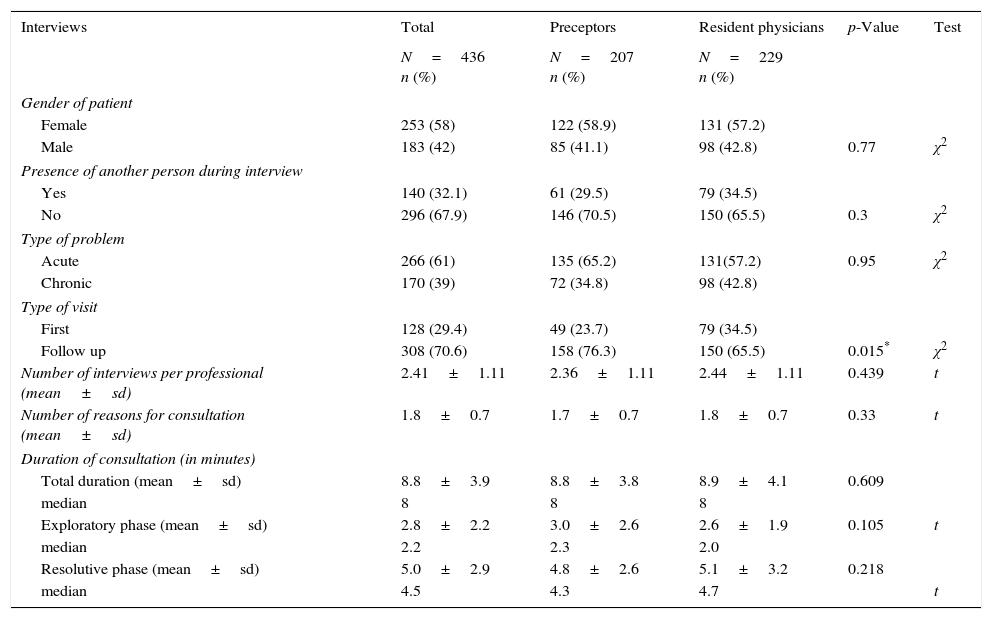

Characteristics of video recorded interviews.

| Interviews | Total | Preceptors | Resident physicians | p-Value | Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=436 n (%) | N=207 n (%) | N=229 n (%) | |||

| Gender of patient | |||||

| Female | 253 (58) | 122 (58.9) | 131 (57.2) | ||

| Male | 183 (42) | 85 (41.1) | 98 (42.8) | 0.77 | χ2 |

| Presence of another person during interview | |||||

| Yes | 140 (32.1) | 61 (29.5) | 79 (34.5) | ||

| No | 296 (67.9) | 146 (70.5) | 150 (65.5) | 0.3 | χ2 |

| Type of problem | |||||

| Acute | 266 (61) | 135 (65.2) | 131(57.2) | 0.95 | χ2 |

| Chronic | 170 (39) | 72 (34.8) | 98 (42.8) | ||

| Type of visit | |||||

| First | 128 (29.4) | 49 (23.7) | 79 (34.5) | ||

| Follow up | 308 (70.6) | 158 (76.3) | 150 (65.5) | 0.015* | χ2 |

| Number of interviews per professional (mean±sd) | 2.41±1.11 | 2.36±1.11 | 2.44±1.11 | 0.439 | t |

| Number of reasons for consultation (mean±sd) | 1.8±0.7 | 1.7±0.7 | 1.8±0.7 | 0.33 | t |

| Duration of consultation (in minutes) | |||||

| Total duration (mean±sd) | 8.8±3.9 | 8.8±3.8 | 8.9±4.1 | 0.609 | |

| median | 8 | 8 | 8 | ||

| Exploratory phase (mean±sd) | 2.8±2.2 | 3.0±2.6 | 2.6±1.9 | 0.105 | t |

| median | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | ||

| Resolutive phase (mean±sd) | 5.0±2.9 | 4.8±2.6 | 5.1±3.2 | 0.218 | |

| median | 4.5 | 4.3 | 4.7 | t | |

In general, the performance level of physicians was almost 100% in terms of politeness and warmth during the interview, facilitating a dialogue with the patient and allowing them to express their doubts. However, few physicians attempted to explore the state of mind of the patient, enquire about their family situation or important stressful events that may have occurred, nor did they ask open questions (Table 3).

Extent to which tasks on the scale were successfully carried out*.

| Total (%) | Preceptors (%) | Resident Physicians (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task 1 | |||

| 1. To what extent did the professional adequately welcome the patient? | 90.3 | 88.4 | 92.1 |

| 2. To what extent did the professional use the computer or logbook without it affecting the level of communication?† | 89.9 | 93.7 | 86.5 |

| 3. To what extent was the professional polite and friendly during the interview? | 99.5 | 99.5 | 99.6 |

| 4. To what extent did the professional make an appropriate use of non-verbal language?† | 89.0 | 83.0 | 94.3 |

| 5. To what extent was the professional empathetic towards the patient when possible?† | 57.5 | 63.2 | 52.3 |

| 6. To what extent did the professional adequately bring the interview to a close? | 90.0 | 88.9 | 91.1 |

| Task 2 | |||

| 7. To what extent was the professional adequately responsive? | 95.6 | 94.7 | 96.5 |

| 8. To what extent did the professional facilitate dialogue with the patient? | 98.9 | 98.5 | 99.1 |

| 9. To what extent did the professional establish and maintain visual eye contact during the interview? | 86.4 | 86.4 | 86.5 |

| 10. To what extent did the professional understand and respond to the patient's questions? | 94.7 | 95.7 | 93.9 |

| 11. To what extent did the professional ask open questions?† | 27.1 | 32.4 | 22.3 |

| 12. To what extent did the professional explore the personal ideas of the patient surrounding the origins and or the causes of their symptoms? | 82.1 | 82.8 | 81.5 |

| 13. To what extent did the professional explore the emotions and feelings that the symptoms or process had caused in the patient? | 35.4 | 39.1 | 32.0 |

| 14. To what extent did the professional explore how the symptoms or process had affected the patient in their everyday, social, family or working life? | 77.4 | 79.1 | 75.8 |

| 15. To what extent did the professional explore the patient's expectations of the consultation? | 95.2 | 97.1 | 93.4 |

| 16. To what extent did the professional explore the state of mind of the patient?† | 22.3 | 28.2 | 17.0 |

| 17. To what extent did the professional explore possible stressful life events that may have occurred to the patient? | 22.9 | 24.2 | 21.8 |

| 18. To what extent did the professional explore the patient's social or family situation?† | 34.0 | 39.6 | 28.9 |

| 19. To what extent did the professional explore risks factors or carry out preventative actions that were not related to the specific consultation? | 57.6 | 60.9 | 54.6 |

| 20. To what extent did the professional summarise the information gathered from the patient? | 11.7 | 11.1 | 12.2 |

| Tasks 3 and 4 | |||

| 21. To what extent did the professional attempt to explain the main symptom or process of the patient's complaint?† | 83.4 | 87.4 | 79.7 |

| 22. To what extent did the professional attempt to explain the stage that would follow after the process? | 81.4 | 85.4 | 77.8 |

| 23. To what extent did the professional offer personalised information that was adapted to the problems and needs of the patient? | 87.9 | 90.2 | 85.9 |

| 24. To what extent did the professional present information clearly? | 85.6 | 87.7 | 83.7 |

| 25. To what extent did the professional give the patient an opportunity and encourage them to participate in the decision-making process during the consultation? | 55.1 | 57.8 | 52.6 |

| 26. To what extent did the professional allow the patient to express his or her doubts? | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 27. If there was at any point a disagreement between the patient and the professional, to what extent did the professional come to a compromise? (entering into a discussion and taking the patient's opinions into consideration). | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| 28. To what extent did the professional ensure that the patient had understood the information given? | 80.1 | 79.1 | 81.1 |

| 29. To what extent did the professional reach a compromise with the patient regarding how to proceed with the treatment? | 70.5 | 72.8 | 68.3 |

Preceptors obtained higher scores in most items, except in exercising non-verbal communication (Table 3).

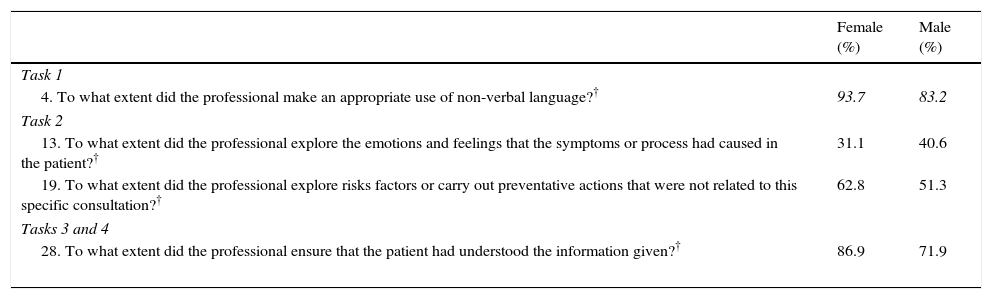

Differences were found in 4 items in relation to the gender of the professional, employing non-verbal communication, the exploration of risk or preventative factors, verifying information and the exploration of emotions and feelings. Male subjects obtained higher scores only in the last item (Table 4).

Level of achievement in the tasks according to gender of the professional*.

| Female (%) | Male (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Task 1 | ||

| 4. To what extent did the professional make an appropriate use of non-verbal language?† | 93.7 | 83.2 |

| Task 2 | ||

| 13. To what extent did the professional explore the emotions and feelings that the symptoms or process had caused in the patient?† | 31.1 | 40.6 |

| 19. To what extent did the professional explore risks factors or carry out preventative actions that were not related to this specific consultation?† | 62.8 | 51.3 |

| Tasks 3 and 4 | ||

| 28. To what extent did the professional ensure that the patient had understood the information given?† | 86.9 | 71.9 |

Regarding the age of professionals, older professionals make better use of the computer (42.1±9.7 and 38.4±8.8; p=0.015); however, younger professionals employed a more appropriate use of non-verbal language (41.0±9.6 and 47.6±8.1; p=0.001) and were better at verifying information (41.2±9.8 and 44.1±9.0; p=0.01). No differences were detected in the rest of items.

In urban centres there was a better use of non-verbal language (92.4% and 82.1%; p=0.002) and the family environment was explored to a greater extent (37.7% and 26.7%; p=0.024). Values for the rest of items were similar.

We also observed differences of up to 40% in the Teaching Units. The most important include the use of appropriate non-verbal language (75% and 100%; p=0.001), bringing the interview to an appropriate close (87% and 96%; p=0.048), the exploration of the state of mind of the patient (18% and 37.5%; p=0.044), summarising the information gathered (3% and 16%; p=0.01) and securing commitments in the action plan (47% and 86%; p=0.001).

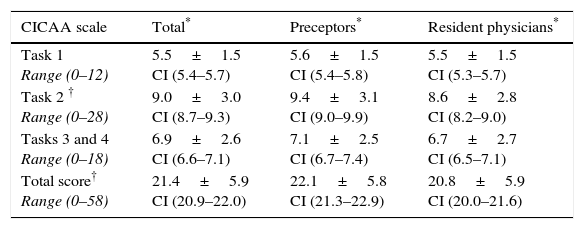

The average total score obtained was 21.4±5.9 points. Preceptors scored higher in Task 2 and in the total score (Table 5). There were no differences in the total score between gender (p=0.89), city (p=0.09) or type of centre (p=0.23).

Quantitative assessment of tasks in the scale.

| CICAA scale | Total* | Preceptors* | Resident physicians* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task 1 Range (0–12) | 5.5±1.5 CI (5.4–5.7) | 5.6±1.5 CI (5.4–5.8) | 5.5±1.5 CI (5.3–5.7) |

| Task 2 † Range (0–28) | 9.0±3.0 CI (8.7–9.3) | 9.4±3.1 CI (9.0–9.9) | 8.6±2.8 CI (8.2–9.0) |

| Tasks 3 and 4 Range (0–18) | 6.9±2.6 CI (6.6–7.1) | 7.1±2.5 CI (6.7–7.4) | 6.7±2.7 CI (6.5–7.1) |

| Total score† Range (0–58) | 21.4±5.9 CI (20.9–22.0) | 22.1±5.8 CI (21.3–22.9) | 20.8±5.9 CI (20.0–21.6) |

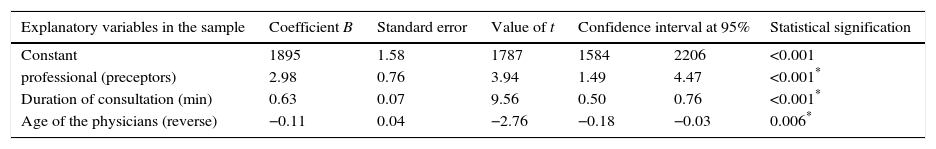

Variables which predict better communication with the patient in multiple linear regression analysis (coefficient of determination: 0.2) include: type of professional (preceptors), duration of consultations and age of the physicians (reverse) (Table 6).

Factors associated with better communication with the patient.

| Explanatory variables in the sample | Coefficient B | Standard error | Value of t | Confidence interval at 95% | Statistical signification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1895 | 1.58 | 1787 | 1584 | 2206 | <0.001 |

| professional (preceptors) | 2.98 | 0.76 | 3.94 | 1.49 | 4.47 | <0.001* |

| Duration of consultation (min) | 0.63 | 0.07 | 9.56 | 0.50 | 0.76 | <0.001* |

| Age of the physicians (reverse) | −0.11 | 0.04 | −2.76 | −0.18 | −0.03 | 0.006* |

Variables included in the model: marital status (as dummy variables), age and gender of the physicians, teaching unit (as dummy variables), type of centre, gender of patient, type of problem, type of visit, companion, duration of consultation, number of patients per day and number of reasons for consultation.

Possible limitations of the study include the fact that physicians participated on a voluntary basis. Despite being the most frequently employed method in studies that use video recordings,15 it is not exempt from a possible selection bias, as participants potentially represents a subgroup of preceptors or resident physicians that are more willing to participate or that have a better communication profile. Furthermore, interviewing real patients has the problem of the random difficulty of the interviews that can influence the results.

Changes in behaviour once the subject is aware he/she is being filmed, can be another problem, although it has been demonstrated that this do not influence the behaviour of physicians nor patients.15 In our work, the minimum recommended recording time was one hour, with a varied selection of consultations for each professional eliminating the first recording.

Finally, due to the inconsistent participation of different Teaching Units, it is difficult to extrapolate the results to the rest of the physicians of the local area.

Task 1. Communicating with patient/familyThe average physician studied excelled in welcoming the patient, bringing the consultation to an appropriate close and employing a good use of non-verbal language. This could have a positive effect on the patient's willingness to divulge information, helping the interview to progress.5 Similar results were obtained by Ruiz-Moral et al.6 in medical hospitals, although they found that 3rd year resident physicians tried very little to welcome the patient, missing potential opportunities that could have been explored.

As other authors have noted,6 empathy is scarcely expressed (60%). There is also indication of a decline in empathy from the university.16,17 Distress, due to physicians being away from their families, working night shifts and unsociable hours, could explain why resident physicians are less empathetic than preceptors.16 In relation to gender, we have not found differences, which other studies have confirmed.17

Non-verbal language is more evident in resident physicians, female physicians, urban centres and in some Teaching Units. Differences in gender between professionals has been previously aforementioned and described.18 It has been proved that the use of these skills helps to increase the patient's ability to understand and cope with his/her illness,19 as well as being understanding when medical errors occur, which helps to preserve and maintain the physician–patient relationship.20

Excluding our study, in which 90% of cases were successful, bringing the interview to an appropriate close is still one of the main difficulties, along with the verification of information, clarity in the action plan or taking precautions.5,21

Task 2. Identify and understand health problems of the patient/familyActive listening skills, a suitable level of reactivity, facilitating dialogue with the patient, understanding and answering their questions and ascertaining their expectations of the consultation are among the strengths demonstrated by the physicians in this task of the interview. However, near a third of the professionals asked open questions, with resident physicians obtaining particularly low scores in this task.

Likewise, they do not attempt to explore the emotional state of the patient, his/her state of mind or family situation. Asking about accidents, stressful life events or potential risk/preventative factors was rare. Nevertheless female professionals were more likely to ask these kind of questions than their male colleages.4,6,21 Unfortunately, professionals rarely summarised information obtained from the patient.

Without considerably increasing the amount of time dedicated to each consultation (30–50s), open questions can help to evaluate the patient's agenda,22 to actively involve him/her, and to obtain more answers and information; which in turn have an effect on the satisfaction of the patient,23 improving the physician–patient relationship and their quality of life.22 Whereas a high level of reactivity and closed questions, inhibits the interview from developing adequately because of interruptions and additional questions.5

Tasks 3 and 4. Reach an agreement with the patient/family surrounding the problem/s and how to deal with them and possible solutions and actionsThe final part of the interview, which consists of informing the patient of the process and the stage that is to follow, verifying that they have understood and obtaining compromises surrounding the action plan are all carried out in 80% of cases. Combined with the fact that in all cases patients were allowed to express their doubts, this could lead us towards consultations based around the patient. However, decision-making is scarcely shared (55%), and cases in which negotiation is required rarely exceed 50%, thus it is clearly an approach in which the doctor is the focal point.

Despite the change in style of consultations that has occurred in the last few years, shared decision-making during consultations is rare,6,7 indeed many patients believe that the physician should make decisions for them, despite the fact that they would like the physician to include them in the process.7 In general, women, young people, those with greater socio-economic means and education, and those with mild illnesses, prefer a method which is centred around the patient, with decision-making being shared.22,23

Quantitative assessmentThe scores obtained from our study are higher than the scores found by Gavilán Moral et al.12 (21.4 and 12.8), possibly because of the patients and physicians, considering also that the physicians of family medicine include hospital physicians, who seem to have a larger focus on the physician.6

Being a preceptor can result in a better level of communication with the patient. This could possibly be due to better interview training for preceptors,4 since age4,24 (reversed in this study) and experience8,9,25 do not necessarily guarantee better communication skills.

However, the differences are not relevant as they only scored 2 points out of 58. In fact, other studies have noted that the communication skills of 4th year resident physicians and of preceptors are similar.8,24 Also a longer consultation, as other authors have noted4,24 results in an improved level of communication. It has also been proved that there is a link between the length of consultations and a better understanding, above all psychosocial from the patient.26 Longer consultations are also linked to consultation styles centred more around the patient,7,22,23 although there still could be an improvement in communication skills without having to necessarily increase the duration of the consultation.9,24

In our study we have not noted any differences in results between the gender of the professionals, however there are occasions in which female professionals allowed the consultation to go on for two minutes longer.18

According to the results aforementioned, Andalusian family physicians excel in terms of creating a friendly and trusting environment, possessing good listening skills and providing the patient with information. Skills to improve include; empathy, asking open questions, exploring the psychosocial sphere of the patient, summarising information and carrying out shared decision-making. Generally speaking, no differences were found between gender or age of the professional nor type of health centre. However, being a preceptor, dedicating more time to each consultation and being younger, are all factors which are associated with a higher level of communication with the patient.

Practical applicationTo improve medical practice it is necessary to establish and maintain a good communicative profile and complement it with a practice which is centred more around the patient. To do this, it will be necessary to reassess the postgraduate and specialisation education and training plans, which will put a greater emphasis on the importance of focusing more on the expectations and worries of the patient.

Once again it has been demonstrated that dedicating an adequate amount of time to each consultation is one of the key factors in the physician–patient relationship.

It would be wise to incorporate the patient's personal perceptions, as well as the point of view of the professionals for future research that may help to better define this relationship.

- 1.

Communication is an essential skill of a physician of family medicine and can help to improve the satisfaction and health of the patient.

- 2.

The preceptor is jointly responsible along with the resident physician for learning how to communicate with the patient.

- 3.

In our country there is a limited amount of literature that describes communication with real patients of preceptors and resident physicians of family medicine.

- 1.

The majority of preceptors and resident physicians of family medicine create a warm and trusting environment during the consultation, excelling in terms of listening skills and informing the patient; however the exploration of the psychosocial sphere and shared decision-making is lacking.

- 2.

Being a preceptor, devoting more time to consultations, and being younger, results in a significant improvement in communication with the patient.

- 3.

The postgraduate study programme should work towards maintaining a good communicative profile of the professional and emphasise communication centred around the patient.

This study was subsidised by a research grant from the Junta de Andalusia (Regional Government of Andalusia) File 0726-2010.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank Virginia Pérez Dominguez for her collaboration on interview assessment.