Campylobacter outbreaks are less common and described than sporadic Campylobacteriosis.

MethodsWe describe the epidemiological investigation including stool examination and bacteriological typing of a Campylobacter outbreak affecting 75 primary school children.

ResultsThe highest risk ratio was associated with the food served 4 days before the peak of cases, namely roast chicken and Russian salad.

DiscussionPoor food preparation practices and deficient kitchen facilities appear to be key issues for cross-contamination of Campylobacter from raw chicken to cooked food.

Los brotes de Campylobacter son menos descritos que los casos esporádicos.

MétodosDescribimos la investigación epidemiológica de un brote en 75 niños de una escuela primaria.

ResultadosLa razón de riesgo más alta se asoció a una comida a base de pollo asado y ensaladilla rusa.

DiscusiónLas deficiencias en los procedimientos de preparación alimentaria y en las instalaciones de cocina parecen ser factores clave en la contaminación cruzada del Campylobacter desde el pollo crudo a la comida cocinada.

Campylobacteriosis is the most frequently reported zoonotic disease in humans in the European Union (EU), with 200,507 reported confirmed cases, and an incidence of 45.2/100,000 in 2007.1 However, Campylobacter outbreaks are rare. Human infection is commonly associated with symptoms including watery and bloody diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fever, headache and nausea, and the infection is usually self-limiting in a few days.2 On 27 September 2010, the director of a Barcelona primary school alerted the Public Health Agency of Barcelona (PHAB) of an unusual rate of 68 absences among 435 scholars, and initial enquiries revealed that children had a diarrhoeal illness. The objective of this present study is to describe the epidemiological, environmental and microbiological investigation of this outbreak and its main results.

MethodsA case was defined as a schoolchild presenting with diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fever or vomiting, and that for this reason was absent from school on the 27 September 2010. We conducted a retrospective cohort study among all schoolchildren exposed to school food during the exposure window (17–21 of September) and conducted a telephone survey of the children's parents, asking for frequency of use of the school canteen, symptoms, time of onset and duration of illness. Nearly all schoolchildren ate the same menu, as a result of a school policy actively promoting a healthy and complete diet. Canteen monitors were therefore only asked about children's mayonnaise intake, the only optional ingredient during the study period. The exposure window was defined from illness onset and Campylobacter incubation time; for each exposure day. The attack rate (AR) of exposed and non-exposed children, as well as the risk ratio (RR) were calculated. PHAB food control authority inspected the school on 28/09, interviewed kitchen staff and collected specimens of the food served on 20, 21, 22 and 23/09 and of tap water, which were examined by PHAB laboratory.

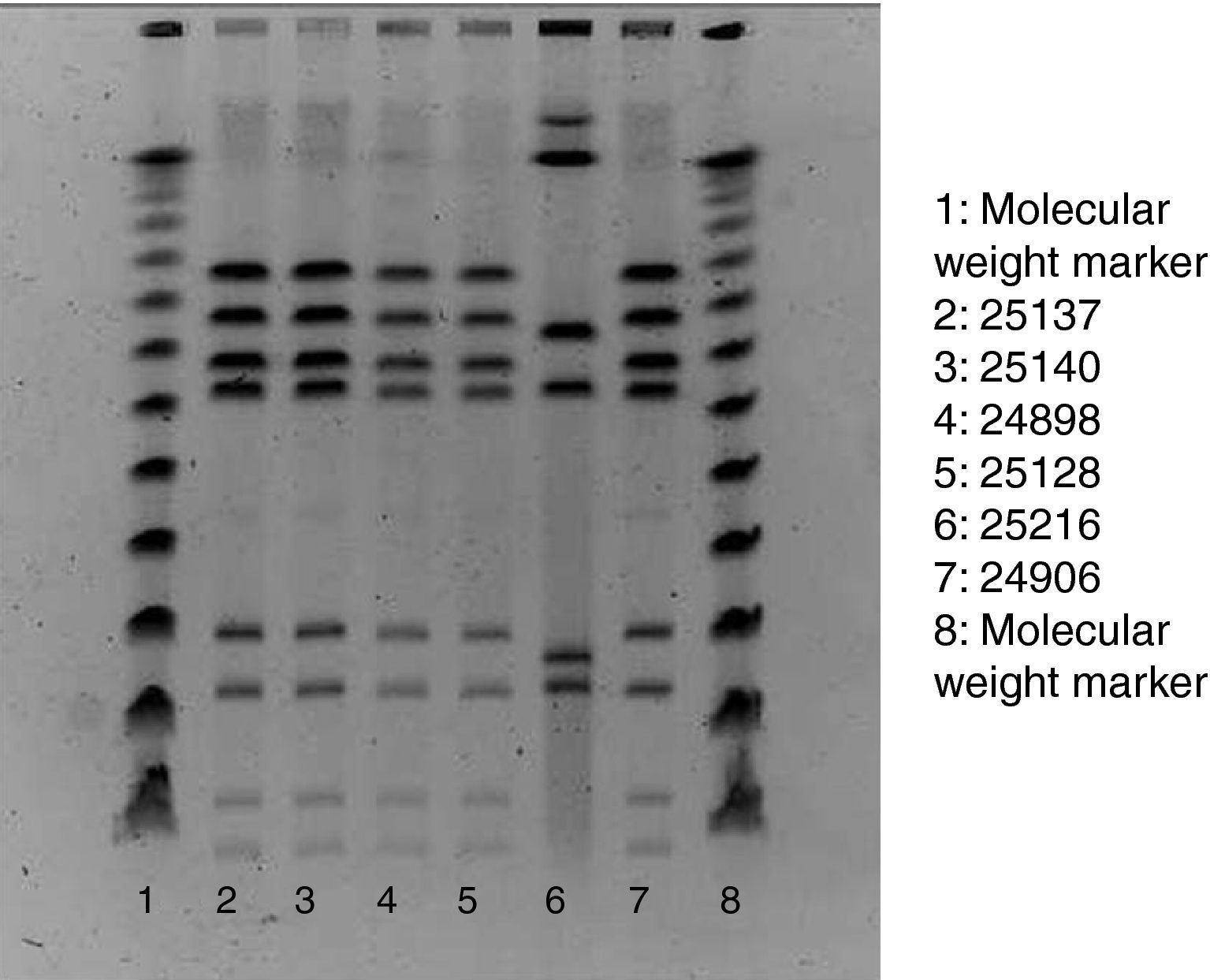

Of the 75 children who fulfilled the case definition, stool samples were provided by 45 cases. All five staff members also provided stool samples, regardless of their health status. Campylobacter, Salmonella, Yersinia enterocolitica and Norovirus was assessed in all samples. Stools specimens were inoculated onto modified charcoal cefoperazone deoxycholate agar (mCCD agar) and Karmali agar. Cultures were then incubated at 41.5°C in a microaerobic atmosphere and examined after 44h. Typical Campylobacter colonies were streaked onto Columbia agar, which was incubated in microaerobic conditions at 41.5°C for 48h. For the confirmation of suspected colonies, pure cultures were examined for oxidase, motility, microaerobic growth at 25°C, aerobic growth at 41.5°C and then tested by the Dryspot Campylobacter agglutination test (Oxoid). Identification of Campylobacter jejuni was performed by detection of hippurate hydrolysis. Food samples were analysed for Campylobacter according to the standard method ISO 10272-1. Test portions were inoculated into a liquid enrichment medium (Bolton broth), homogenized and incubated in microaerobic atmosphere at 37°C for 6h, and then at 41.5°C for 44h. The cultures obtained were inoculated into mCCD agar and Karmali agar. Tap water samples were analysed by the membrane filtration method. The filters were incubated in Bolton broth at 37°C for 44h in microaerobic atmosphere. Isolation and confirmation of C. jejuni were performed by the same protocol used in stool samples. In order to establish the clonal relationships of the identified isolates of Campylobacter, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of restriction fragments of the chromosomal DNA was performed, following the SmaI (Roche) restriction enzyme and protocol3 (Fig. 1).

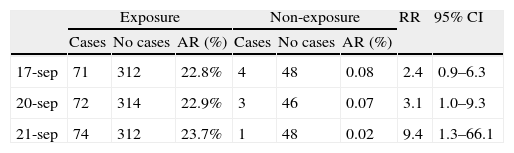

ResultsOut of the 435 potentially exposed schoolchildren, 75 were affected (AR=17.2%). Ninety per cent of affected children had diarrhoea, 90% abdominal pain, 77% fever (median: 38.5 °C), 31% vomiting and 27% nausea. Twenty-four children consulted their paediatrician, and 2 were hospitalised. The median age of cases was 6 years, and 52% of them were boys. After the onset of 1 case on 22 September, the number of cases rose sharply to reach a peak of 30 new cases on 25 September and decreased then rapidly to zero in 3 days. The median illness duration was 3 days. Table 1 shows the date-specific AR, RR and 95% CI for each exposure day, discarding the weekend days of 18 and 19 September. The highest risk ratio between exposed and non-exposed children was found on 21st September (RR=9.4, 95% CI: 1.3–66.1). On that day the canteen food was roast chicken and Russian salad, optionally served with mayonnaise. The risk ratio of eating mayonnaise on 21st September was not significant (1.08, 95% CI: 0.57–2.03). The highest overall AR was found in the nursery school (25%), whereas the 5th year of primary school showed the highest AR (26%). Stool samples were provided by 45 cases, 29 of which (64.4%) were positive for C. jejuni (1 of them also being positive for Salmonella serotype 04). Among the Campylobacter strains tested with pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, 5 of the 6 showed the same restrictions pattern. Food and water samples were negative for all the studied microorganisms, including Campylobacter spp. The food control authority found deficiencies in the school kitchen facilities and in the food handling process, such as the use of the same surface for raw and cooked food processing, the proximity of the vegetables cutter to the cooking area and the lack of an automatic tap device.

Number of cases and no cases for each day of the exposure window, AR, RR and 95% CI. AR: attack rate; RR: relative risk; and 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

| Exposure | Non-exposure | RR | 95% CI | |||||

| Cases | No cases | AR (%) | Cases | No cases | AR (%) | |||

| 17-sep | 71 | 312 | 22.8% | 4 | 48 | 0.08 | 2.4 | 0.9–6.3 |

| 20-sep | 72 | 314 | 22.9% | 3 | 46 | 0.07 | 3.1 | 1.0–9.3 |

| 21-sep | 74 | 312 | 23.7% | 1 | 48 | 0.02 | 9.4 | 1.3–66.1 |

Campylobacter outbreaks are fairly uncommon and represent only 0.2% of all cases of Campylobacteriosis.4 Outbreaks are mainly foodborne and commonly occur in institutions.5 The microbiological characteristics of the organism, the lack of public health follow-up of cases and the incomplete strain characterization in microbiology laboratories might be some of the reasons behind the unexpectedly low incidence of outbreaks. The major role in Campylobacter transmission to humans seems to come from food of animal origin, especially poultry,6 handled in poor hygienic conditions. Within the European community, Campylobacter isolation rate in broiler chickens ranged from 0 to 86.5% in 2007 (55.8% in Spain).1 Undercooking and cross-contamination are well described ways of transmission of Campylobacter.7,8 During food preparation, the bacteria can be transferred from chicken to hands and from these to ready-to-eat foods, with a rate ranging from 2.9 to 27.5%.9 Since Campylobacter is quite infective, one drop of raw chicken juice can result in human illness.2 This school outbreak was probably caused by C. jejuni present in the chicken prepared on 21st September. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that contamination occurred on 20th September, when the AR was smaller but still significant. Both undercooking and cross-contamination from raw chicken to the Russian salad and the roasted chicken might have been the underlying causes. Cross-contamination may have occurred due to the small surface for handling for both raw and cooked food, through the contamination of kitchen gadgets or the hands of food handlers. Another possible mechanism might have been the leakage of the raw chicken juice onto a ready-to-eat food such as the Russian salad in the cold-store. All such contaminations were plausibly enhanced by the lack of good food-handling practices (use of gloves, frequent hand washing, presence of a foot-activated tap in the kitchen). It is not surprising that Campylobacter was not found in the food analysed, since the bacteria cannot withstand the freezing temperature legally required for the storage of food in restaurants. Freezing has been reported to lower Campylobacter counts by >2 logs.10 The finding that 1 out of 6 Campylobacter strains had a different restriction pattern than the rest probably shows a sporadic case, quite a common fact when considering that Campylobacteriosis is the leading cause of bacterial gastroenteritis. Finally, the absence of Campylobacter in tap water agrees with the finding that the few Campylobacter outbreaks associated with mains drinking water were almost exclusively related with unchlorinated water.11 In Spain, a similar outbreak took place in a Madrid school in 2003, where 81 children were affected after eating custard, probably cross-contaminated with C. jejuni from a raw chicken.8 In 2005, 79 employees of a Copenhagen company developed a diarrhoeal illness after consuming a chicken salad that had also been cross-contaminated by raw chicken.12 We believe it is crucial to detect and investigate such outbreaks in order to enlighten their risk factors and to prevent practices like poor food handling hygiene, which would play a key role in the fight against infection and its impact on children.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

We thank all the people who collaborated with the investigation, the children and their parents, school teachers and monitors, as well as the nurses and other members of the work team of the Public Health Agency of Barcelona who helped a lot in the investigation.