El número de denuncias por maltrato presentadas por los padres contra sus hijos a nivel nacional se ha incrementado de forma alarmante sobre todo a partir del año 2005. El objetivo de este estudio era comprobar si los menores infractores denunciados por maltrato a sus progenitores presentan diferentes problemas psicológicos que los infractores por otros delitos y los adolescentes no infractores. Para ello se analizaron los datos de 231 adolescentes entre 14 y 18 años del País Vasco (España) de ambos sexos, de los cuales 106 eran infractores y el resto procedía de la población general. Algunos de los infractores tenían delitos por violencia filio-parental (n = 59) mientras que el resto tenían delitos de otro tipo (n = 47). Los infractores que agreden a sus padres se caracterizan por presentar más problemas conductuales fuera del hogar y características asociadas a la sintomatología depresiva que los infractores por otros delitos o los que no son infractores. Determinados problemas psicológicos de los hijos podrían precipitar situaciones de conflicto en el seno familiar y los progenitores verse incapaces de controlarlos. Los resultados ponen de relieve la necesidad de que los infractores por violencia filio-parental reciban terapia psicológica individual.

The number of complaints filed by parents against their children nationwide has increased dramatically, particularly since 2005. The aim of this study was to examine whether young offenders who had been charged for violence against their parents presented different psychological problems from youngsters charged with other types of offence and non-offenders. Data from 231 adolescents of both sexes aged 14 to 18 years and living in the Basque Country (Spain) were analyzed. Of these, 106 were offenders and the rest were from a community sample. Some of the offenders had been charged with child-to-parent violence (n = 59), while the rest of them had not (n = 47). Offenders who had assaulted or abused their parents presented more behavior problems outside home and more characteristics associated with depressive symptomatology than offenders of other types or non-offenders. Certain psychological problems in adolescents could precipitate family conflict situations and leave parents unable to control their children. Findings highlight the need for offenders charged with child-to-parent violence to receive individual psychological therapy.

In recent years, child-to-parent violence (CPV) has attracted increasing interest at both the scientific and clinical levels. An extensive review by Gallagher (2008) revealed that the prevalence of CPV worldwide is estimated at between 10% and 18%, while in the United States and Canada the prevalence figures for CPV range from 5% to 29% (Bobic, 2004; Downey, 1997; Laurent & Derry, 1999; Straus & Gelles, 1990). In Europe, research shows that this problem has been on the increase in the last few years (Wilcox & Pooley, 2012). It is surprising that although the victims (parents) are socially and economically (and in some cases even physically) more powerful than their children, it is still the children who wield control and power over their parents (Paterson, Luntz, Perlesz, & Cotton, 2002). The majority of current definitions of child-to-parent violence are based on Cottrell (2001), who identifies as the children's ultimate objective that of obtaining power and control over their parents. However, research on CPV does not evaluate the children's intentions (which are very difficult to study), but rather the different types of violent behaviors (physical, psychological, emotional, and financial).

Studies carried out so far on child-to-parent violence have yielded no conclusive results about the psychological functioning of juveniles who assault or abuse their parents (Kennedy, Edmonds, Dann, & Burnett, 2010) or about their clinical profile. On the other hand, there is some evidence that juveniles who have a record of CPV offences are more likely to have psychological disorders than those previously charged with other types of offence and present higher rates of hospitalization and psychotropic medication use (e.g., Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012; Kennedy et al., 2010; Micucci, 1995). According to some studies, the most common diagnostic categories in this group, following the DSM-V classification (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), would be Disruptive, Impulse-Control and Conduct disorders and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (González-Álvarez, Gesteira, Fernández-Arias, & García-Vera, 2010; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012). In the study by Ibabe and Jaureguizar (2012), 77% of the psychological disorders in young offenders were found in these diagnostic categories.

The majority of expert researchers in child development agree with Achenbach and Edelbrock (1978) in classifying behavior problems in terms of internalizing and externalizing manifestations. Externalizing behavior problems - characterized by a lack of control over one's emotions - would include difficulties in interpersonal relations and rule breaking, as well as irritability and aggressiveness. As for internalizing behavior problems - characterized by excessive emotional control - these would include social isolation, demand for attention, and feelings of uselessness, inferiority and/or dependence. Some meta-analyses suggest that boys show more externalizing behavior than girls (e.g., Evans, Davies, & DiLillo, 2008), whereas there are no differences as regards internalizing symptoms (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003). However, there are contradictory results on gender differences with regard to internalizing and externalizing behaviors, the explanation for which is as yet unclear (DeJonghe, von Eye, Bogat, & Levendosky, 2011). It may be that some discrepancies are due to the influence of the children's age, given that a previous study found an interaction between age and sex for clinical maladjustment (Bernaras, Jaureguizar, Soroa, Ibabe, & Cuevas, 2013). As regards child-to-parent violence (externalizing symptom), higher rates of CPV have been found in sons in judicial and clinical contexts: 2 or 3 times higher than the rates for daughters (Gallagher, 2008; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2010). However, in studies with the general population no significant differences were found between boys and girls for physical violence or the differences were very small (Calvete et al., 2013; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011; Jaureguizar, Ibabe, & Straus, 2013). These results are in line with the Gallagher's (2008) conclusions that the more serious the adolescent's violent behavior against parents, the greater the differences between boys and girls. On the other hand, girls use more verbal violence against their parents than boys (Evans & Warren-Sohlberg, 1988; Nock & Kazdin, 2002).

Juveniles who are violent towards their parents present externalizing symptoms in contexts outside the home, often displaying antisocial and delinquent behaviors (Jaureguizar et al., 2013). As regards the socio-educational context, previous research suggests that children who are violent against their parents are characterized by presenting a range of problems related to school maladjustment (Cornell & Gelles, 1982; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012; Kratcoski, 1985) or low interest in learning (Paulson et al., 1990). Moreover, these youngsters tend to associate with peer groups who also present violent behaviors in and outside the home (Agnew & Huguley, 1989). This violent profile has been found not only in studies with clinical or judicial samples; research analyzing child-to-parent violence in community samples has also revealed that young people who attack their parents tend to present more antisocial behaviors and other aggressive behaviors (towards teachers or within the peer group) than adolescents who are not violent towards their parents (Calvete, Orue, & Sampedro, 2011; Jaureguizar et al., 2013). As far as substance abuse is concerned, more in-depth study is required, but there is empirical evidence of the relation between alcohol and/or drug use and child-to-parent violence (Calvete, Orue & Gámez-Guadix, 2013; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012; Pagani et al., 2009). Even so, it has been shown that aggression by sons/daughters against their parents does not usually occur under the effect (in the children) of alcohol or other drugs (Evans & Warren-Sohlberg, 1988; Walsh & Krienert, 2007). Although these results may appear somewhat contradictory, they are in fact coherent: in the long-term, substance use in adolescents may lead to situations of family conflict given the consequences of such use (e.g., poor academic performance, money problems or staying out late at night).

Among the little research that has demonstrated the existence of internalizing symptoms in adolescents who are violent towards their parents, it should be mentioned that some relation has been found between violent behavior and depressive symptomatology (Calvete et al., 2013; Paulson, Coombs, & Landsverk, 1990) or characteristics associated with depressive symptomatology, such as low self-esteem (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012). In line with such findings, in a study carried out in the United States, juveniles who had been charged with CPV presented higher rates of suicide attempts and psychological stress than those with a record of other types of offence (Kennedy et al., 2010). Drug use tends to be preceded by some type of emotional distress (Shedler & Block, 1990) and in turn, substance use can make people more vulnerable to depressive symptoms (Blanco & Sirvent, 2006). There is also evidence that a negative family climate can lead to depression in children and adolescents. For example, Tuisku et al. (2009) found that the perception of lower family support on the part of adolescents was associated with depressive symptoms. If further research confirms that juveniles reported for CPV present a different clinical profile from those charged with offences outside of the home, the former will need specialized intervention.

Given that the research carri ed out to date on child-to-parent violence has scarcely addressed the study of the psychological and clinical profile of the juveniles involved, the aim of the present study was to analyze the externalizing and internalizing problems of children and adolescents reported for CPV, by comparison with those who had committed other offences and adolescents from the community sample. This would provide key information so that the juveniles in question can be diagnosed and treated more effectively. Secondly, we set out to explore the possible gender differences in these adolescents' manifestation of certain psychological problems, as well as in the different types of child-to-parent violence. And finally, we tried to identify the externalizing and internalizing symptoms that best predict child-to-parent violence using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The hypotheses were as follows:

a) Adolescents that have been reported by their parents will present higher rates of substance use and externalizing symptoms outside the home than juveniles charged with other types of offence (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012) or those with no record of delinquency.

b) Girls will present higher levels of psychological and emotional child-to-parent violence (Evans & Warren-Sohlberg, 1988; Nock & Kazdin, 2002), but fewer behavior problems outside the home (Evans et al., 2008).

c) Behavior problems outside the family context will be better predictors of CPV than depressive symptomatology, in accordance with the findings of previous studies which indicate an important relationship with behavior problems.

Method

Participants

The sample was made up of 231 adolescents aged 14 to 18 (M = 16.46, SD = 1.15) from the Basque Country (Spain), of both sexes (66% boys). Of this total, 106 were offenders (59 had been reported by their parents for being violent towards them, and 47 had committed offences outside the home context) and the rest (n = 125) were non-offenders. Of the offenders, 81% were currently serving some kind of sentence. To obtain a control group, we selected 125 adolescents from a larger sample (n = 485), also from the Basque Country, taking into account the offenders' sex and age1. Boys accounted for 75% of the CPV offenders, 72% of the other offenders, and 60% of the non-offenders, while mean age of the participants in each group was, respectively, 16.41, 16.77, and 16.37.

Instruments

Intra-family violence (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011). This 9-item instrument was created to measure violence within the family, and includes 3 subscales: intimate partner violence, violence by parents against children, and child-to-parent violence. In the present study we used only the CPV subscale for evaluating physical, psychological, and emotional violence according to Cottrell's (2001) definitions. Response format was a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = never to 5 = many times) and respondents indicated whether the behavior was directed toward the father or the mother (e.g., "I insult or threaten my father when I get angry for any reason"). The difference between psychological and emotional violence is theoretically supported by numerous scientific articles (e.g., Cottrell, 2001; Howard & Rottem, 2009; Kennair & Mellor, 2007) and empirically by the results of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011). We carried out a principal components analysis and used the Varimax rotation method. According to the standard criterion (initial eigenvalues higher than 1), we defined 3 factors that explained 88.85% of the total variance. The first refers to physical violence, was defined by 2 items and explained 50% of the variance. The second factor, made up of 2 items, explained 20% of the variance and referred to psychological CPV. The third factor was made up of 2 items, explained 18% of the variance, and referred to emotional CPV. In the present study the internal consistency of the CPV scale (α = .80) was good, as well as that of the three types of violence (physical, α = .85; psychological, α = .88; emotional, α = .87). An item was added to the original scale for assessing "financial violence" ("I steal money or things from my parents").

Multi-factor Self-Assessment Child Adjustment Test [Test Autoevaluativo Multifactorial de Adaptación Infantil - TAMAI] (Hernández, 2004). This test is self-applied by children and adolescents aged 8 to 18, individually or in groups. It rates personal maladjustment (e.g., somatization, affective depression, cognipunitiveness [distorted view of oneself and of reality that leads burdening on oneself the tension or stress one is experiencing] or intropunitiveness [negative self-esteem, self-hate, and self-punishment]), school maladjustment (e.g., school indiscipline, aversion to the teacher, hypomotivation or hypo-effort), and social maladjustment (e.g., social self-maladjustment includes social aggressiveness and dysnomia [tendency for non-observation of rules or rebellion against them]). This instrument also includes two subscales referring to family relations (family dissatisfaction and dissatisfaction among siblings). For all of these dimensions there were 115 statements with yes/no response. An item example for the case of school maladjustment would be "I behave very badly in class". Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the subscales ranged from .70 to .92 (Hernández, 2004). In the present study the personal maladjustment (α = .83) and school maladjustment (α = .75) subscales showed acceptable levels of internal consistency, but that of social maladjustment (α = .46) yielded a less than desirable value (α < .70).

Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC, Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). This instrument comprises 12 subscales for assessing both positive dimensions (4 adaptive subscales) and negative dimensions (8 clinical subscales). In the present study we applied 5 subscales: 1 positive (self-esteem) and 4 clinical (sensation-seeking, social stress, anxiety, and external locus of control), with a total of 50 true/false items. An example for social stress would be "I feel out of place when I'm with people". Alpha coefficients of the scales used ranged from .73 to .83.

Millon Adolescent Clinical Inventory (MACI, Millon, 2004). This instrument was designed to assess personality traits and clinical syndromes in adolescents and comprises 27 subscales. In this study was administered only the Substance Abuse Proneness subscale. The MACI is deemed suitable only for adolescents from clinical population, and for this reason we applied the TAMAI and some subscales of the BASC (both instruments that can be applied to the general population), which permitted comparison of the three groups. The Substance Abuse Proneness subscale comprises 10 items with true/false response options. An example of an item would be "I got used to trying out hard drugs to see what effect they had". Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the subscale for this study was .73. Apart from this, participants were asked a specific question about the frequency of illegal substance use: "I have used illegal substances (hashish/marijuana, ecstasy/designer drugs, cocaine, speed/ amphetamines, or others) in the past year". Response format was a 5-point Likert-type scale (from 1 = never to 5 = many times).

Magallanes Scale of Identification for Attention Deficit [Escala Magallanes de Identificación de Déficit de Atención en Adolescentes - ESMIDA-J] (García-Pérez & Magaz, 2006). This is a self-applied test for adolescents aged 14 to 18 and serves to identify behavioral markers for Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Attention-Deficit Disorder without Hyperactivity (ADD). It consists of 20 items with 4-point Likert-type response format (from 1 = ever or almost never to 4 = very rarely). An item example would be "I feel restless, nervous or uneasy when I'm not doing anything". The subscale associated with ADHD yielded a Cronbach's alpha of .78, while the alpha value for the subscale associated with ADD was .63.

Procedure

Once the necessary authorizations had been obtained from the institutions involved, the young offenders were assessed individually at the Juvenile Court of Vizcaya (Spain) by the psychosocial team or at one of the Basque Country's reform schools (there are 15 of them) by the youth worker responsible, in accordance with the corresponding data-collection protocol. This protocol set down the instructions for those responsible for the schools and the psychosocial team in relation to the informed consent from parents and the correct application of the assessment instruments described. The sample of non-offender adolescents was obtained through schools and the instruments were administered in classroom groups and in the presence of a member of the research team.

Selection of the original sample of non-offender adolescents (n = 485) was carried out by means of non-random sampling, depending on the disposition of the schools involved, whose participation was voluntary. In this selection process we took into account type of school (public vs. private), language model (Spanish and Basque vs. Basque only) and school year of the adolescents, with a view to obtaining a balanced and representative sample. This sample came from 9 schools in the Basque Country, and to form a group of non-offenders (n = 125) the selection was made at random, taking as a reference the sex and age of those in the offender group. Participating students handed in the informed consent form signed by their parents to their class tutors. Application of the questionnaires and assessment instruments took between 45 and 90 minutes, depending on the participants' school year

Data analysis

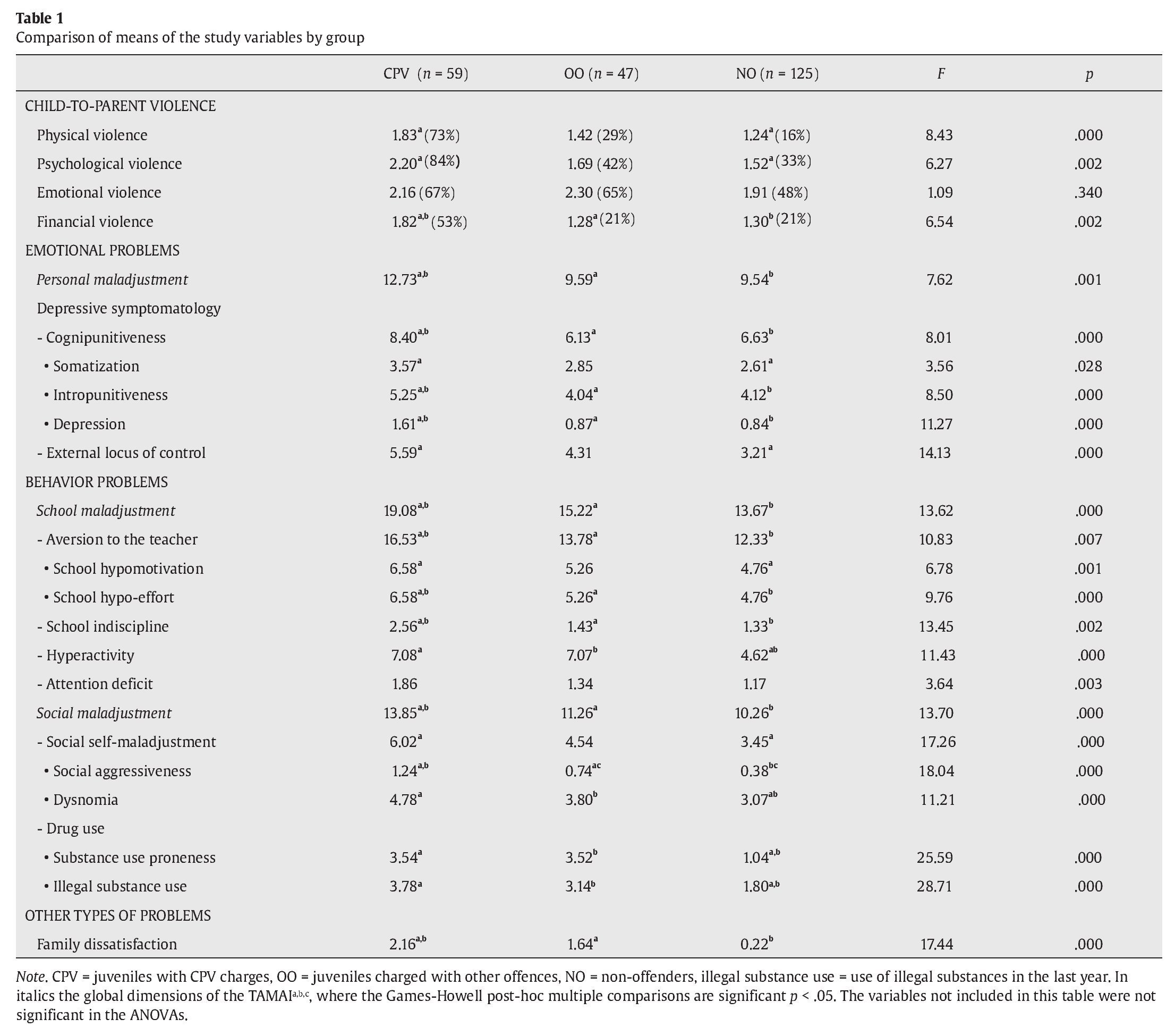

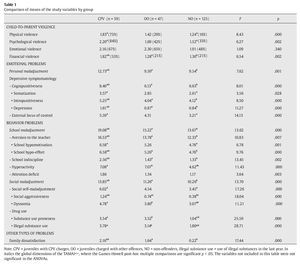

The univariate statistical analyses were carried out with the SPSS 20 program. Firstly, one-factor variance analyses were carried out with the group factor (CPV offenders, other offenders, and non-offenders) and the dependent variables categorized as child-to-parent violence, problems associated with depressive symptomatology (personal maladjustment, cognipunitiveness, and external locus of control) and behavior problems outside the family context (school and social maladjustment), and problems of other types (family dissatisfaction). Some of the mentioned variables encompassed more specific variables, and this was taken into account on drawing up Table 1. Subsequently, Games-Howell post-hoc analyses for multiple comparisons were carried out. Secondly, the correlation matrix between observed variables was obtained.

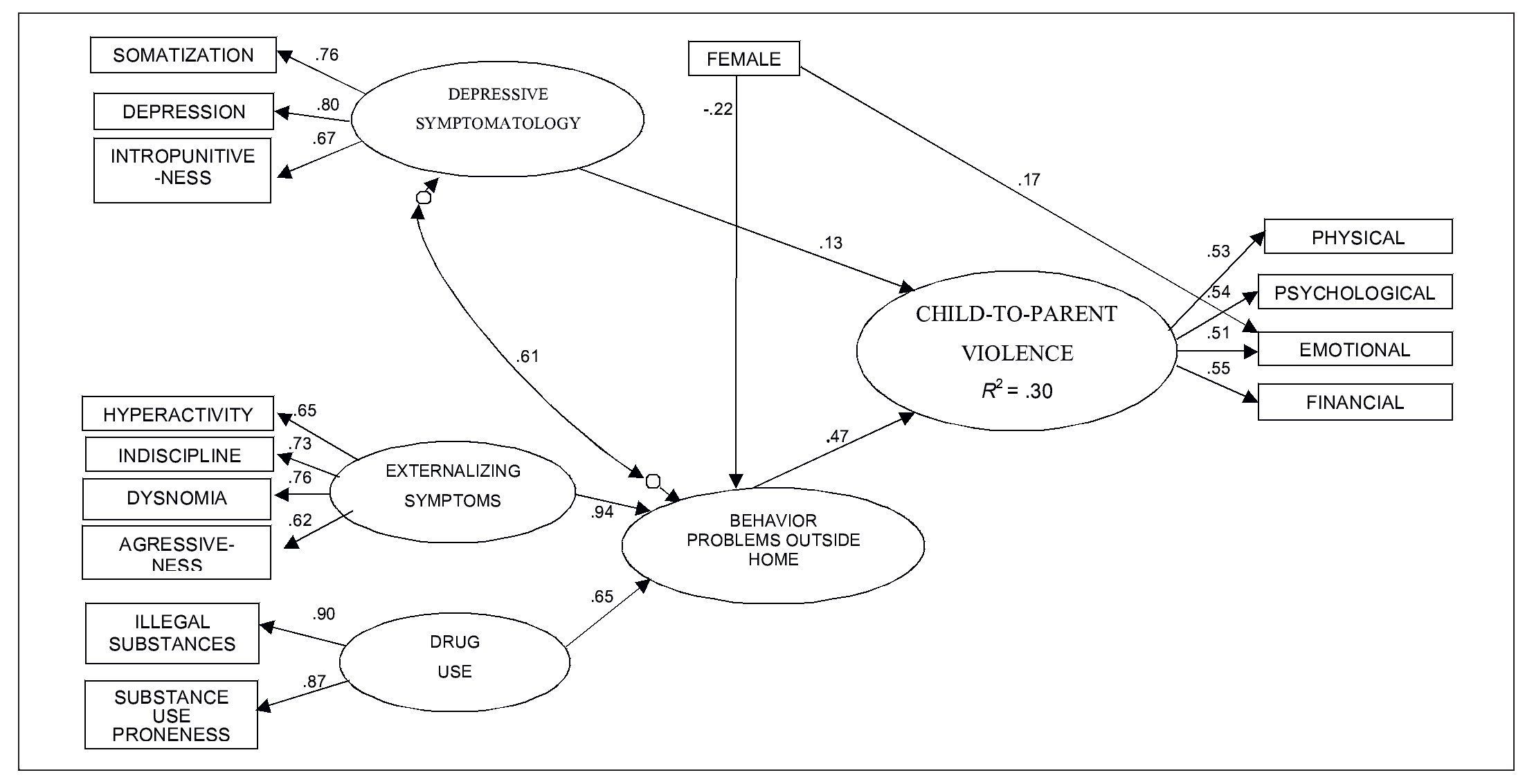

The aim was to create a simple structural model with few variables and that made theoretical sense, was easily interpretable with good fit to the model data, and showed good predictive capacity (Batista-Foguet & Coender, 2000); hence, it was necessary to exclude from the model some variables of the Table 1. The EQS 6.1 Structural Equation Program was used for assessing whether the proposed model was appropriate. The initial confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assessed the adequacy of the measurement model and the relation between the latent variables. The first-order latent variables included in the CFA were: depressive symptomatology (indicators: somatization, intropunitiveness, and depression), externalizing symptoms (indicators: hyperactivity, school indiscipline, dysnomia, and social aggressiveness), substance use (indicators: tendency to abuse drugs, use of illegal substances), and child-to-parent violence (indicators: physical, psychological, emotional, and financial violence). Moreover, a second-order latent variable was included, behavior problems outside the home (latent variables: externalizing symptoms and substance use).

Next, we drew up the SEM model for examining the predictive capacity of the adolescents' depressive symptomatology and behavior problems outside the family context for child-to-parent violence. We did not rule out the possibility that socio-demographic variables could predict violence against parents. Therefore, we examined the results of the Lagrange multiplier test (Chou & Bentler, 1990) with the aim of assessing whether other parameters should be included in the model so as to improve the fit and the level of explanation.

A series of fit indexes were calculated, including: (a) general χ2, (b) comparative fit index (CFI), (c) Bentler-Bonnet non-normative fit index (NNFI), (d) the Bollen incremental fit index (IFI), and (e) Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). The Chi-squared (χ2) statistical marker was used to assess the difference between the proposed models and the saturated models. The practical fit indexes used were the IFI, CFI, and NNFI and values of over .90 were expected for these markers (Bentler, 2006). The RMSEA index was used for measuring the reasonable error of approximation in terms of goodness of fit and the values of the RMSEA index (.01, .05 and .08) indicate excellent, good, and mediocre fit, respectively (MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996).

The analyses were carried out with the complete information using the maximum likelihood method (e.g., Arbuckle, 1996; Jamshidian & Bentler, 1998). The normalized Yuan, Lambert, and Fouladi (2004) kurtosis coefficient was low (6.52). In some univariate distributions a lack of normality was detected: physical child-to-parent violence (asymmetry = 2.12, kurtosis = 2.66) and financial child-to-parent violence (asymmetry = 2.22, kurtosis = 4.95).

Results

Physical and financial violence against parents is at the root of many cases in which the parents report their child to the police or other authorities. A total of 73% of CPV offenders stated that they have used physical violence against their parents at some time, but this is also the case for 29% of other offenders and 16% of adolescent non-offenders. Moreover, 53% of CPV offenders reported having perpetrated so-called "financial violence", as well as 21% of other offenders and 21% of adolescent non-offenders.

Comparisons of Means by Group

Table 1 shows the comparisons of means of the study variables by group. Juveniles reported by their parents for CPV present more physical, psychological and financial violence than non-offenders. Also, considering the percentages, CPV offenders, by comparison with other young offenders, presented higher rates of physical, χ2(1, N = 89) = 10.46, p = .001, φ = .44; psychological, χ2(1, N = 89) = 10.66, p = .001, φ = .44; and financial violence, χ2(1, N = 96) = 7.07, p = .008, φ = .33. The three original groups were formed in accordance with their parents' reports of CPV. The cases reported normally involve serious assault or abuse and repeated violent behavior by children against their parents over a number of years. However, in the present study we also took into account sporadic violent behavior against parents and mild physical violence. Therefore, the results obtained in the comparison of means of CPV by group need not be considered incompatible.

Furthermore, the CPV group adolescents score higher in variables related to depressive symptomatology (cognipunitiveness, intropunitiveness, and depression) and personal maladjustment than those in the other groups. On the other hand, the CPV group shares with the "other offences" group certain emotional problems (external locus of control, hypomotivation, and somatization), in contrast to the non-offender group.

As regards behavior problems, the CPV group shows higher levels of school maladjustment (aversion to the teacher and school indiscipline) and social maladjustment (social aggressiveness) than the other two groups. Finally, the two offender groups present greater level of hyperactivity, dysnomia, and drug use than the non-offender group.

Mean scores for personal, school, and social maladjustment of the CPV group were at a "medium-high" level (from percentile 61 to percentile 80). However, the non-offender group presented a "medium" level (from percentile 41 to percentile 60) for the three types of maladjustment (personal, school, and social).

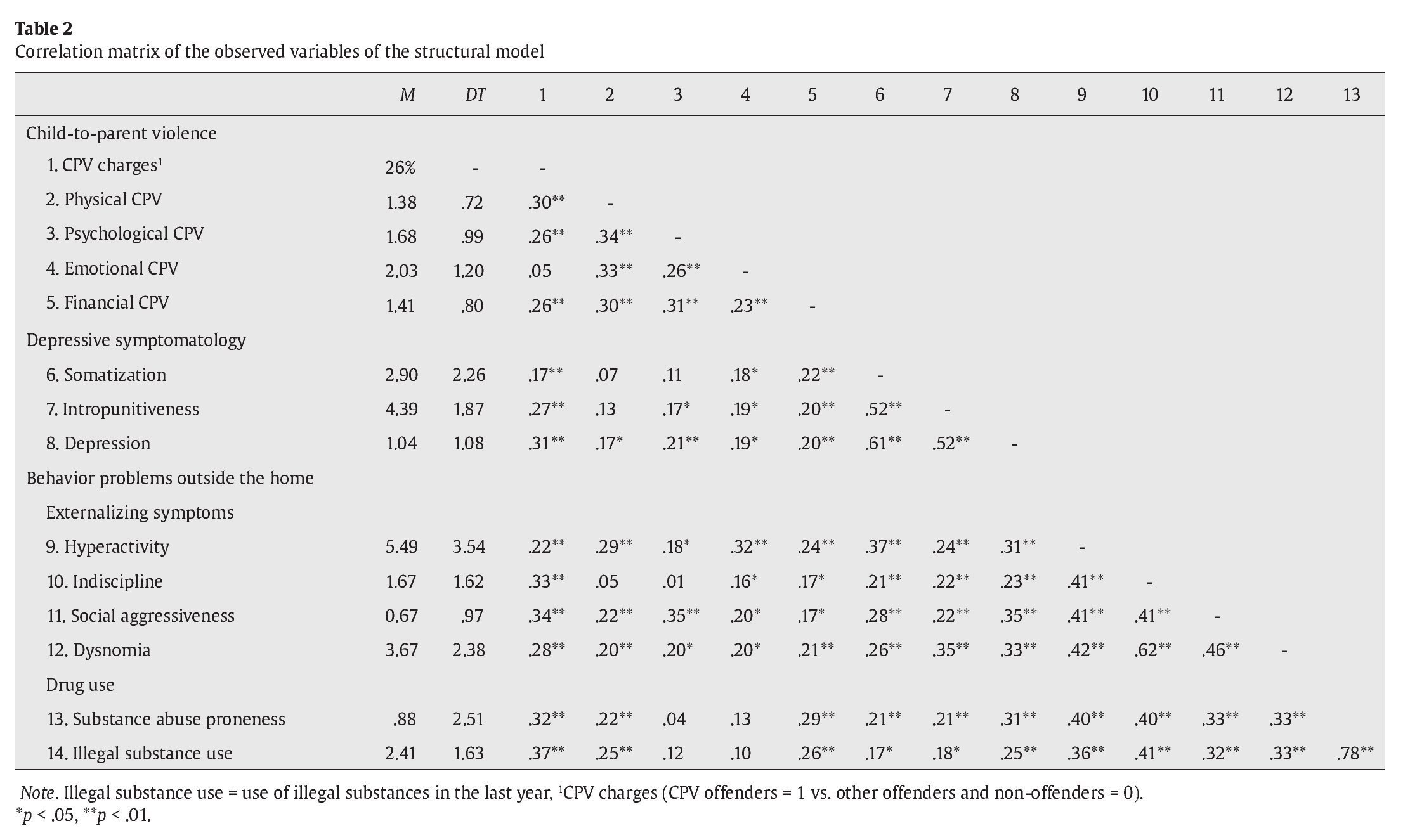

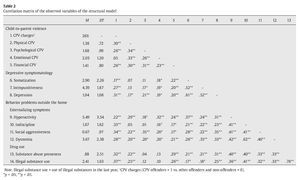

Correlation Matrix between the Observed Variables

As can be seen in Table 2, physical CPV correlated above all with various externalizing symptoms (hyperactivity, social aggressiveness, dysnomia), drug use, and depression. Emotional violence and financial violence were positively associated with all the variables categorized as depressive symptomatology, as well as with the variables designated as externalizing symptoms (hyperactivity, indiscipline, social aggressiveness, and dysnomia), while substance use (substance abuse proneness and illegal substance use) correlated significantly with physical and financial violence. The significant correlations were of moderate to low intensity (Cohen, 1988)

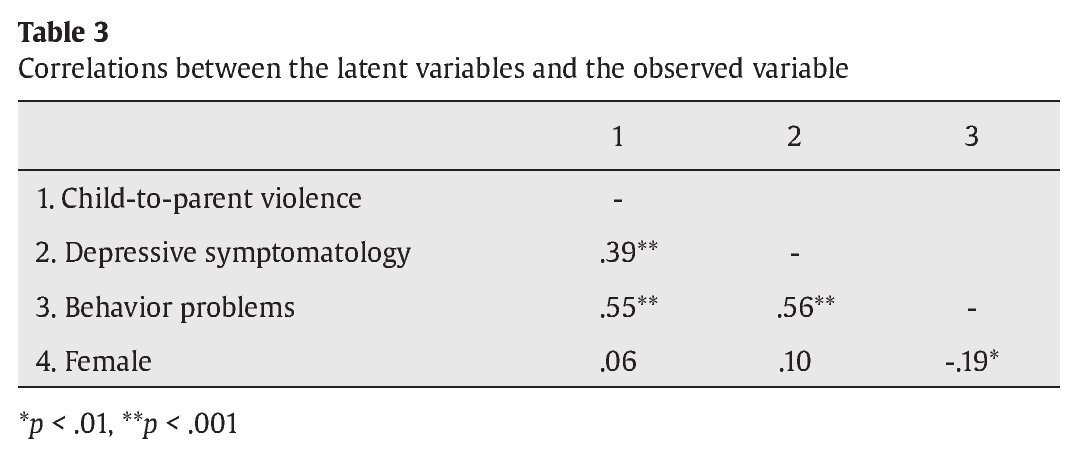

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

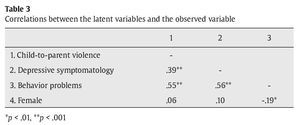

An initial confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated the pertinence of the measurement model proposed and the associations between the latent variables and an observed variable. All the factor loadings and the associations between the latent variables were significant (p < .001). Table 3 shows the correlations between the latent variables and sex. In terms of the Cohen (1988) effect size, child-to-parent violence was moderately associated with depressive symptomatology (r = .39, p < .001) and with behavior problems (r = .55, p < .001); on the other hand, depressive symptomatology and behavior problems outside the home were significantly related (r = .56, p < .001). However, being a girl was only inversely associated with behavior problems (r = -.19, p < .001). The fit indexes for the CFA model were adequate: ML, χ2(70, N = 231) = 111.87, CFI = .99, NNFI = .98, IFI = .98, RMSEA =. 051; Yuan-Bentler, χ2(70, N = 231) = 106.42, CFI = .99, NNFI = .99, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .048.

Structural Model

The fit indexes of this model were acceptable with the maximum likelihood method: ML, χ2 (71, N = 231) = 110.65, p < .001, CFI = .99, NNFI = .98, IFI = .98, RMSEA =. 049, while with the Yuan-Bentler (2000) robust method the fit of the data to the model improved slightly, χ2(71, N = 231) = 105.03, CFI = .99, NNFI = .99, IFI = .99, RMSEA = .046 (see Figure 1). In accordance with the robust standard errors, all the factor loadings were significant for p < .001. The structural model explained 30% of the variance of child-to-parent violence. The behavior problems factor significantly predicted CPV (β = .47, p < .001), while depressive symptomatology did not (β = .13, p > .05). Moreover, there was a positive and significant relation between depressive symptomatology and behavior problems in adolescent sons and daughters (r = .61, p < .001). Being female emerged as a significant predictor of emotional CPV (β = .17, p < .001) and of behavior problems (β = -.22, p < .001). According to these results, girls perpetrate more emotional violence against parents than boys, but present fewer behavior problems outside the home.

Figure 1. Structural model of the predictors of child-to-parent violence. Note. Goodness of fit N = 231; ML, χ (71) = 110.65, CFI = .99, NNFI = .98, IFI = .99 RMSEA = .049. All the standardized coefficients are significant (p < .001), except that of depressive symptomatology (p > .05).

Finally, we tested an alternative model incorporating the observed variable CPV Group (CPV offenders = 1 vs. other offenders and non-offenders = 0) as a predictor of the latent variables. The results indicate acceptable fit: ML, χ2(83, N = 231) = 154.45, p < .001, CFI =.96, NNFI = .95, IFI = .96, RMSEA =. 06; Yuan-Bentler, χ2 = 147.54, CFI = .97, NNFI = .96, IFI = .97, RMSEA = .06. In this model, offenders reported for CPV were significantly associated with higher levels of child-to-parent violence (β = .47, p < .001), more depressive symptomatology (β = .34, p < .001), and more behavior problems outside the home (β = .47, p < .001).

Discussion

The present study compared samples from different contexts (judicial and community) with a view to obtaining the clinical profile of juveniles who assault their parents. Young offenders charged with child-to-parent violence show a different psychological profile from those of other offenders and non-offenders, with more behavior problems outside the home and emotional problems. It was hypothesized that adolescents who had been reported by their parents would present more behavior problems outside the home than those charged with other types of offence (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012) or non-offenders. This hypothesis was confirmed on our finding that the CPV group showed higher rates of school maladjustment (school indiscipline, aversion to the teacher) and social maladjustment (social aggressiveness) than the other two groups. These results would be in the line of those from other studies, since the profile of adolescents who assault their parents includes school adjustment problems (Ibabe et al., 2009) and violent behaviors outside the family environment (Agnew & Huguley, 1989; Jaureguizar et al., 2013). On the other hand, and predictably, the two offender groups shared high scores in a range of behavior problems characteristic of young offenders in general (substance abuse proneness, use of illegal substances, hyperactivity, attention deficit, dysnomia, and social self-maladjustment).

Previous studies had found that alcohol and/or drug use predicted child-to-parent violence (Calvete et al, 2013; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012). The results of the present study provide a new picture, since the offenders' profile is clear: substance abuse proneness and use of illegal substances are much higher in the two offender groups than in the non-offender group. The novelty of the present study's findings resides, however, in the fact that juveniles reported for violence against their parents present higher levels of personal maladjustment, with a notable incidence of symptoms associated with depressed state (cognipunitiveness - affective depression and intropunitiveness - and poor school performance) by comparison with other young offenders and non-offenders. Although few studies have focused on the analysis of emotional problems, it is important to note that these adolescents had already been identified with a profile showing more depressive symptomatology and more psychological stress, compared to those who were not violent towards their parents (e.g., Calvete et al., 2013; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012; Kennedy et al., 2010). In the light of this empirical evidence it can be stated that child-to-parent violence is not solely the result of dysfunctional family relations, but is also related to behavior disorders (Kennedy et al., 2010) and emotional disorders in the juveniles involved. On the other hand, it should be noted that no significant differences were found between the three groups for self-esteem, despite the findings of some previous research that young offenders who assaulted their parents had lower self-esteem than offenders who did not commit violence against their parents (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012). However, it should also be pointed out that intropunitiveness, which encompasses negative self-esteem, self-hate and self-punishment is related to CPV.

Secondly, and in relation to gender differences in the violence perpetrated, we expected to find higher levels of psychological and emotional violence against parents in daughters (Evans & Warren-Sohlberg, 1988; Kennair & Mellor, 2007; Nock & Kazdin, 2002) and lower rates of behavior problems. Our hypothesis was confirmed for emotional violence and for behavior problems, but there were no differences between boys and girls as regards psychological abuse. Traditionally, it has been considered that males are more aggressive than females, both in situations of domestic violence and in those of peer violence (Archer, 2004; Paulson et al., 1990). According to the structural model, the rate of behavior problems outside the family context was lower in girls, but there were no significant differences with regard to emotional symptoms. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere (Evans et al., 2008; Kitzmann et al., 2003).

As far as the prediction of child-to-parent violence is concerned, it should be highlighted that behavior problems (hyperactivity, indiscipline, social aggressiveness, and substance use) outside of the home are better predictors of CPV than emotional problems revolving basically around depressive symptomatology. In a previous study, Calvete et al. (2013) also found that two behavioral characteristics of sons and daughters (drug use and proactive violence) predicted CPV. The finding related to substance use is also coherent with those of diverse previous studies on CPV (e.g., Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2011; Pagani et al., 2009). There is a well-known relationship between substance use and increased aggressiveness in interpersonal and family relations (e.g., Brook, Brook, Rosen, De la Rosa, Montoya, & Whitman, 2003). On the other hand, research has indicated that in adolescence, depressive symptomatology may precede the abuse of various chemical substances (Hovens, Cantwell, & Kiriakos, 1994), and in turn such abuse leads to symptoms associated with depression (Blanco & Sirvent, 2006).

The relation between CPV and proactive violence supports claims about the instrumental use of violence by adolescents against their parents (Calvete et al., 2013). The fact that CPV offenders present more behavior problems than other young offenders and non-offenders leads one to think that certain psychological problems in adolescents can precipitate situations of conflict in the family context or vice versa. This difference found in CPV offenders may be due to these problems not having been diagnosed and adequately treated from the psychological point of view and because of the parents' difficulty for controlling their children's inappropriate behaviors (e.g., depressive symptomatology or drug abuse).

The relation between multi-level maladjustment (personal, school, and social) and antisocial and delinquent behaviors is well documented (e.g., Arce, Fariña, & Vázquez, 2011; Lösel & Bender, 2003). Maladjustment was greater in CPV offenders than in the other two groups, and the rates yielded can be classed as quite high. The clinical characteristics found in the CPV group, some of which are shared with the other young offenders group, are compatible with those in the attention deficit disorders group and the disruptive behaviors group (including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, dissocial disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder), and this finding is in line with those of a previous study (Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2012). Regardless of the psychological disorders in these youngsters, violent behavior by children against their parents indicates a failure of high-risk adolescents to learn the appropriate social and emotional skills for properly regulating their behaviors and emotions. The results of the present study confirm the need for children in these situations to receive individual psychological therapies. The cognitive-behavioral perspective has shown itself to be the most effective in numerous behavior disorders (Yen et al., 2013). Such techniques could help to achieve changes in these youngsters as regards both the way they behave and the way they think (values, beliefs, and attitudes).

In this study it has been shown that children and adolescents who assault their parents are characterized by presenting various types of maladjustment, emotional imbalance associated with depressed state, and family dissatisfaction — characteristics traditionally associated with parental deprivation (e.g., Bengoechea, 1996) — and more recently with permissive-neglectful or indifferent parenting styles (Cottrell & Monk, 2004); this issue should be addressed in future research.

Limitations

The principal limitation of the present study would be that, as occurs in cross-sectional research, we cannot establish causal relationships between emotional or behavior problems and child-to-parent violence, but only treat them as predictors (not causes) of this phenomenon. Another limitation would be related to the data-collection methodology, as there could be problems of data validity: it is likely that some adolescents, even when responding to questionnaires anonymously and confidentially, fail to admit having assaulted their parents, either out of shame or fear of social rejection, so that the prevalence of CPV is underestimated. Even so, this problem has been resolved, in part, through the information obtained on reported cases of CPV and other information provided by the Juvenile Courts.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest.

Note

1The non-offender group is somewhat larger than the other two groups, so as to avoid problems in the statistical analyses arising from the small number of participants and missing values. Nevertheless, it was confirmed that there were no significant differences between the three groups by sex, χ2 (2, N = 231) = 4.99, p = .08, or age, χ2 (8, N = 231) = 10.68, p = .22.

Manuscript received: 24/10/2013

Revision received: 17/03/2014

Accepted: 03/06/2014

*Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Izaskun Ibabe.

Departamento de Psicología Social y Metodología de las Ciencias del Comportamiento. Facultad de Psicología. Universidad del País Vasco.

Avda. Tolosa, 70. 20018 Donostia-San Sebastián. Spain.

E-mail: Izaskun.ibabe@ehu.es

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2014.06.004

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. (1978). The classification of child psychopathology: A review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1275-1301.doi:10.1037//0033-2909.85.6.1275

Agnew, R., & Huguley, S. (1989). Adolescent violence toward parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51, 699-711. doi: 10.2307/352169

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques (pp. 243-277). Mahwah, NJ: LEA.

Arce, R., Fariña, F., & Vázquez, M. J. (2011). Grado de competencia social y comportamientos antisociales, delictivos y no delictivos en adolescentes [Social competence and delinquent, antisocial, and non-deviant behavior in adolescents]. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 43, 473-486.

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 8, 291-322. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291

Batista-Foguet, J. M., & Coenders, G. (2000). Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales [Structural equation modeling]. Madrid, Spain: La Muralla.

Bengoechea, P. (1996). Un análisis comparativo de respuestas a la privación parental en niños de padres separados y niños huérfanos en régimen de internado [A comparative analysis of response to parental loss in orphans and children of separated parents in a boarding school]. Psicothema, 8, 597-608.

Bentler, P. M. (2006). EQS, Structural Equations Program Manual. Encino, CA: Multivariate Statistical Software, Inc.

Bernaras, E., Jaureguizar, J., Soroa, M., Ibabe, I., & Cuevas, C. (2013). Evaluación de la sintomatología depresiva en el contexto escolar y variables asociadas [Evaluation of depressive symptomatology and related variables in a school context]. Anales de Psicología, 29, 131-140.

Blanco, P., & Sirvent, C. (2006). Psicopatología asociada al consumo de cocaína y alcohol [Psychopathology associated with cocaine and alcohol consumption]. Revista Española de Drogodepencias, 31, 324-344.

Bobic, N. (2004). Adolescent violence towards parents. Australian Domestic and Family Violence Clearinghouse. Retrieved from http://www.austdvclearinghouse.unsw.edu.au/topics.htm

Brook, D. W., Brook, J. S., Rosen, Z., De la Rosa, M., Montoya I. D., & Whitman, M. (2003). Early risk factors for violence in Colombian adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1470-1478. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1470

Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2013). Child-to-parent violence: Emotional and behavioral predictors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 755-772. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455869

Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Sampedro, R. (2011). Violencia filio-parental en la adolescencia: Características ambientales y personales [Child-to-parent violence in adolescence: Environmental and individual characteristics]. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 34, 349-363.

Chou, C., & Bentler, P. M. (1990). Model modification in covariance structure modelling: A comparison among likelihood ratio, Lagrange multiplier, and Wald tests. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25, 115-136.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: LEA.

Cornell, C. P., & Gelles, R. J. (1982). Adolescent to parent violence. Urban and Social Change Review, 15, 8-14.

Cottrell, B. (2001). Parent abuse: The abuse of parents by their teenage children. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Health Canada, Population and Public Health Branch, National Clearinghouse on Family Violence.

DeJonghe, E. S., von Eye, A., Bogat, G. A., & Levendosky, A. A. (2011). Does witnessing intimate partner violence contribute to toddlers' internalizing and externalizing behaviors? Applied Developmental Science, 15, 129-139. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2011.587713

Downey, L. (1997). Adolescent violence: a systemic and feminist perspective. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 18, 70-79. doi: 10.1002/j.1467-8438.1997. tb00272.x

Evans, E. D., & Warren-Sohlberg, L. (1988). A pattern of analysis of adolescent abusive behaviour towards parents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 3, 201-216. doi: 10.1177/074355488832007

Evans, S. E., Davies, C., & DiLillo, D. (2008). Exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent outcomes. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13, 131-140. doi: 10.1016/ j.avb.2008.02.005

Gallagher, E. (2008). Children's violence to parents: A critical literature review (Master's thesis). Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. http://web.aanet.com.au/eddiegallagher/Violence%20to%20Parents%20-%20Gallagher%202008.pdf

García-Pérez, E. M., & Magaz, A. (2006). Escala Magallanes de identificación de déficit de atención [Magallanes Scale for the identification of attention deficit]. Bilbao, Spain: Grupo Albor-Cohs.

González-Álvarez, M., Gesteira, C., Fernández-Arias, I., & García-Vera, M. P. (2010). Adolescentes que agreden a sus padres. Un análisis descriptivo de los menores agresores [Adolescents who assault their parents. A descriptive analysis of juvenile offenders]. Psicopatología Clínica Legal y Forense, 10, 37-53.

Hernández, P. (2004). Test Autoevaluativo Multifactorial de Adaptación Infantil: TAMAI [Multi-factor Self-Assessment Child Adjustment Test - TAMAI]. Madrid, Spain: TEA.

Hovens, J. G. F. M., Cantwell, D. P., & Kiriakos, R. (1994). Psychiatric comorbidity in hospitalized adolescent substance abusers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33, 476-483. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199405000-00005

Howard, J., & Rottem, N. (2009). It all starts at home: Male adolescent violence to mothers. A research report. Melbourne, Australia: Inner South Community Health Service Inc and Child Abuse Research Australia, Monash University. Retrieved from http://www.ischs.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/It_all_starts_at_home1.pdf

Ibabe, I., & Jaureguizar, J. (2010). Child-to-parent violence: Profile of abusive adolescents and their families. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 616-624. doi: 10.1016/j. jcrimjus.2010.04.034

Ibabe, I., & Jaureguizar, J. (2011). ¿Hasta qué punto la violencia filio-parental es bidireccional? [To what extent is child-to-parent violence bi-directional?]. Anales de Psicología, 27, 265-277.

Ibabe, I., & Jaureguizar, J. (2012). Perfil psicológico de los menores denunciados por violencia filio-parental [The psychological profile of young offenders with charges of child-to-parent violence]. Revista Española de Investigación Criminológica, 6, 1-19.

Ibabe, I., Jaureguizar, J., & Díaz, O. (2009). Adolescent violence against parents: Is it a consequence of gender inequality? The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 1, 3-24.

Jamshidian, M., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). A quasi-Newton method for minimum trace factor analysis. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, 62, 73-89. doi: 10.1080/00949659808811925

Jaureguizar, J., Ibabe, I., & Straus, M. A. (2013). Violent and prosocial behavior by adolescents toward parents and teachers in a community sample. Psychology in the Schools, 50, 451-470. doi: 10.1002/pits.21685

Kennair, N., & Mellor, D. (2007). Parent abuse: A review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 38, 203-219. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0061-x

Kennedy, T. D., Edmonds, W. A., Dann, K. T. J., & Burnett, K. F. (2010). The clinical and adaptive features of young offenders of child-parent violence. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 509-520. doi: 10.1007/s10896-010-9312-x

Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt, A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to IPV: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 71, 339-352. doi: 10.1037/0022- 006X.71.2.339

Kratcoski, P. C. (1985). Youth violence directed toward significant others. Journal of Adolescence, 8, 145-157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(85)80043-9

Laurent, A., & Derry, A. (1999). Violence of French adolescents toward their parents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 21-26. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00134-7

Livingston, L. R. (1986). Children's violence towards single mothers. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 13, 920-933.

Lösel, F., & Bender, D. (2003). Protective factors and resilience. In D. P. Farrington & J. W. Coid (Eds.), Early prevention of antisocial behaviour (pp. 130-204). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1, 130-149. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

Micucci, J. A. (1995). Adolescents who assault their parents: A family systems approach to treatment. Psychotherapy, 32, 154-161.

Millon, T. (2004). MACI. Inventario Clínico para Adolescentes [MACI. Adolescent Clinical Inventory]. Madrid, Spain: TEA.

Nock, M. K., & Kazdin, A. E. (2002). Parent-directed physical aggression by clinic-referred youths. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 31, 193-205. doi: 10.1207/ S15374424JCCP3102_05

Pagani, L., Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D., Zoccolillo, M., Vitaro, F., & Duff, P. (2009). Risk factor models for adolescent verbal and physical aggression toward fathers. Journal of Family Violence, 24, 173-182. doi: 10.1007/s10896-008-9216-1

Paterson, R., Luntz, H., Perlesz, A., & Cotton, S. (2002). Adolescent violence towards parents: Maintaining family connections when the going gets tough. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 23, 90-100. doi: 10.1002/j.1467-8438.2002. tb00493.x

Paulson, M. J., Coombs, R. H., & Landsverk, J. (1990). Youth who physically assault their parents. Journal of Family Violence, 5, 121-133. doi: 10.1007/BF00978515

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). Sistema de Evaluación de la Conducta de Niños y Adolescentes [Behavior assessment system of children-BASC]. Madrid, Spain: TEA.

Shedler, J., & Block, J. (1990). Adolescent drug use and psychological health: A longitudinal inquiry. American Psychologist, 45, 612-630.

Straus, M. A., & Gelles, R. J. (1990). Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Tuisku, V., Pelkonen, M., Kiviruusu, O., Karlsson, L., Ruuttu, T., & Marttunen, M. (2000). Factors associated with deliberate self-harm behaviour among depressed adolescent outpatients. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1125-1136. doi: 10.1016/j. adolescence.2009.03.001

Walsh, J. A., & Krienert, J. L. (2007). Child-parent violence: An empirical analysis of offender, victim, and event characteristics in a national sample of reported incidents. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 563-574. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9108-9

Wilcox, P., & Pooley, M. (2012, September). Responding to child to parent violence. 12th Annual Conference of the European Society of Criminology, Eurocrim, Bilbao, Spain.

Yen, C. F., Chen, Y. M., Cheng, J. W., Liu, T. L., Huang, T. Y., Wang, P. W., ... Chou, W. J. (2013). Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on improving anxiety symptoms, behavioral problems and parenting stress in Taiwanese children with anxiety disorders and their mothers. Child Psychiatry Human Development, 45, 338-347. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0403-9

Yuan, K. H., Lambert, P. L., & Fouladi, R. T. (2004). Mardia's multivariate kurtosis with missing data. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 3, 413-437.