Suicidal behaviour has not yet been analysed from a network approach in adolescent samples. It is imperative to incorporate new psychological models to understand suicidal behaviour from a different perspective. The main objective of this work was twofold: (a) to examine suicidal behaviour through network analysis and (b) to estimate the psychological network between suicidal behaviour and protective and risk factors in school-age adolescents.

MethodParticipants were 443 students (M=14.3 years; SD=0.53; 51.2% female) selected incidentally from different schools. Different instruments were administered to assess suicidal behaviour, emotional and behavioural difficulties, prosocial behaviour, subjective well-being, emotional intelligence, self-esteem, depressive symptomatology, empathy, positive and negative affect, and emotional regulation.

ResultsThe resulting network of suicidal behaviour was strongly interconnected. The most central node in terms of strength and expected influence was “Consider taking your own life”. In the estimated psychological network of suicidal behaviour and risk and protective factors, the nodes with the highest strength were depressive symptomatology, positive affect, and empathic concern. The most influential nodes were those related to emotional intelligence abilities. Suicidal behaviour was positively connected to depression symptoms and negative affect, and negatively connected to self-esteem and positive affect. The results of the stability analysis indicated that the networks were accurately estimated.

ConclusionsSuicidal behaviour can be conceptualized as a dynamic, complex system of cognitive, emotional, and affective characteristics. The new psychopathological and psychometric models allow us to analyse and understand human behaviour and mental health problems from a new perspective, suggesting new forms of conceptualization, evaluation, intervention, and prevention.

Broadly speaking human behaviour is complex by nature, and its understanding and analysis requires more sophisticated psychological models that go beyond a linear, static and unicausal1 view. It is well known that human behaviour does not conform well to the linear and unilateral. Mental health and emotional well-being as part of the inherent diversity of human behaviour require approaches that are open to different and novel ways of analyzing, understanding and intervening upon mental health problems. Here, we could mention different approaches such as, for example, the dynamic systems theory, the network analysis, the chaos theory or the catastrophe theory.2

Specifically, the network model has emerged with new vigour in psychopathology as a response to, among other things, some of the problems associated with the biomedical “common latent cause” model3–5 (e.g., reification, commodification, tautological reasoning, discrete or categorical nature), used primarily in clinical psychology and psychiatry. In essence, the biomedical approach starts from the premise that symptoms and signs, such as anhedonia, suicidal ideation, rumination, etc., have a common, unobservable origin, called mental disorder (e.g., depression). In this sense, mental disorder would be the underlying cause that explains the covariation between observable symptoms and signs at the phenotypic level. This common latent cause view has relevant implications at multiple levels.6,7 It is plausible that this way of conceptualising mental disorders is one of the obstacles, though not the only one, preventing progress in this scientific field. For this reason, many voices are calling for a radical paradigm shift and a profound reconceptualisation of classification systems,2,8,9 with the network model (and network analysis) being one of the possible solutions.

The network model views psychological problems as a complex system of symptoms (or signs, traits, mental states, etc.) that impact or interact with each other in a causal way causal.3,4,10,11 Therefore, an underlying latent variable would not be the common cause of the covariance between symptoms. This approach is presented as a novel and different way to analyse and understand psychological phenomena such as suicide.12,13 In essence, this approach may allow for a more detailed appreciation of mental health and therefore could usefully contribute to the refinement of existing explanatory models in this field,14 to the search for aetiological markers and/or to the establishment of new therapeutic targets, among other aspects.

Suicidal behaviour is a complex, multidimensional and multicausal phenomenon whose delimitation, assessment, treatment and prevention requires a holistic, person-centred approach that includes biological, psychological and social variables.15–17 Suicidal behaviour is a multifaceted concept that refers not only to completed suicide, but also to suicidal ideation and communication. In this sense, suicidal behaviour is understood to encompass different manifestations, which range in severity from suicidal ideation and suicidal ideation to completed suicide, through communication (e.g., threat) and suicide attempt.15,16 Depending on the expression (death ideation, suicidal attempt, etc.) within this continuum of severity, the level of risk of completed suicide for a particular person will theoretically be higher.

Completed suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents and young adults aged 15–29 years worldwide, and is one of the leading causes of years of life lost due to premature death and years lived with disability.15–18 In Spain, in 2017, there were 3679 suicides, with the rate varying depending on the autonomous communities and sociodemographic factors.19,20 In 2018, according to the figures available on the website of the National Statistics Institute (INE for its initials in Spanish), a total of 3539 people died by suicide in Spain. Specifically, in 2018, 268 people aged 15–29 took their own lives in Spain. Prevalence rates of suicidal behaviour in adolescents globally and nationally are high. In a recent meta-analysis,21 the lifetime prevalence and annual prevalence of attempted suicide in adolescents were found to be 6% (95% CI 4.7–7.7%) and 4.5% (95% CI 3.4–5.9%), respectively. The lifetime prevalence and annual prevalence of suicidal ideation was 18% (95% CI 14.2–22.7%) and 14.2% (95% CI 11.6–17.3%), respectively. In samples of adolescents and young adults, females have a higher risk of attempted suicide (OR 1.96; 95% CI 1.54–2.50), and males of completed suicide (HR 2.50; 95% CI 1.8–3.6).22 In Spain, the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation in the adolescent population is around 30%, while the prevalence of suicide attempts is approximately 4%.15,23–25

Young people who display suicidal behaviour in any of its expressions (e.g., ideation, communication, gesture) report, among others, a higher number of emotional and behavioural problems, increased substance use, more risk-taking and impulsive behaviour, and poorer quality of life, self-esteem and emotional regulation.25–30 In addition, suicidal behaviour has been associated with a wide range of risk and protective factors.22,28,29,31–33 Risk factors include, to name a few, the presence of mental disorder, previous attempts, psychological factors (e.g., hopelessness, impulsivity, cognitive rigidity), family history of previous disorders or attempts, and history of abuse. Protective factors include, among others, problem-solving skills, social skills, and social and family support. There is no doubt that an adequate understanding, assessment and intervention in suicidal behaviour requires analysis of both the phenomenon itself (e.g., frequency, intensity, duration) and associated risk and protective factors, as well as analysis of previous and current psychopathology and possible triggers.15,22,34,35

Suicidal behaviour is a major health problem, both because of its prevalence and because of the personal, family, educational and socio-health consequences it entails. At the same time, a large proportion of the psychological problems observed in adulthood have their roots in childhood and adolescence. In this sense, adolescence is a relevant stage of human development. It can be seen as a sensitive time “window” in which it is advisable to implement actions to promote emotional well-being and prevent mental health problems. For example, developing early detection and early intervention programmes before the different expressions of suicidal behaviour (e.g., ideation) increase in severity. It would also be interesting to incorporate new psychological and psychometric models to conceptualise, understand and address suicidal behaviour during adolescence in a different light. However, to date, no analysis of suicidal behaviour and its relationship with different cognitive, emotional and behavioural indicators in adolescents has been carried out under the network model.

Within this research framework, the main aim of this study was twofold: (a) to analyse the network structure of suicidal behaviour in an incidental sample of adolescents and (b) to estimate the psychological structure of the network between suicidal behaviour and different risk and protective factors (emotional and behavioural difficulties, prosocial behaviour, subjective well-being, emotional intelligence, self-esteem, depressive symptomatology, empathy, positive and negative affect, and emotional regulation). It is hypothesised that psychometric indicators of suicidality (e.g., ideation and act), as measured by the Paykel36 Scale, will be positively interconnected. At the same time, in the estimated psychological network of suicidal behaviour and risk and protective factors, it is expected that indicators of emotional well-being (positive affect, well-being, prosocial behaviour, self-esteem, emotional intelligence, etc.) and those referring to problematic issues will be found to be positively interconnected and those referring to emotional and behavioural problems (suicidal behaviour, hyperactivity, emotional problems, negative affect, depressive symptomatology, etc.) will be closely interconnected at the intra-domain level (dimensions of the same valence), and at the same time inversely associated at the inter-domain level (between risk factors and protective factors).

MethodParticipantsIncidental sampling was used in this study. The initial sample consisted of a total of 473 participants. Students over 19 years of age (n=13) or who did not complete the entire survey were eliminated (n=17). The sample consisted of 443 students in the third year of Compulsory Secondary Education from six different schools (state and grant-maintained) in the Autonomous Community of La Rioja. Of the total, 216 (48.8%) were male and 227 (51.2%) were female. The average age was 14.31 years (SD=0.61), ranging from 13 to 16 years (13–14 years, n=327; 15 years, n=102; 16 years, n=14). Exclusion criteria were: (a) absence of informed consent; (b) diagnosed neurological or medical illness; and (c) previous or current history of mental health problems.

ToolsPaykel Suicide Scale, PSS36It is a tool designed for the assessment of suicidal behaviour. It consists of a total of five items with a dichotomous Yes/No response system (scores 1 and 0, respectively). Specifically, it assesses thoughts of death (items 1 and 2), suicidal ideation (items 3 and 4) and suicide attempts (item 5). Total scores range from 0 to 5. The time frame to which the questions refer is the previous year. A higher score refers, at a theoretical level, to greater severity. The PSS has been used previously in Spanish teenagers, demonstrating appropriate psychometric quality.15,23,25

Personal Wellbeing Index-School Children, PWI-SC37,38The PWI-SC was developed to assess subjective well-being in school-aged children and adolescents.37,38 It consists of a total of eight items where the response options range from 0 (Very unhappy) to 10 (Very happy). The first item of the scale analyses “life as a whole”. The other seven items include satisfaction with: health, standard of living, things achieved in life, how secure they feel, groups of people they are part of, security in the future, and relationships they have with other people. The PWI-SC has shown adequate psychometric properties in previous international and national studies.37,39,40

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, SDQ41The SDQ is an instrument used to assess behavioural and emotional difficulties and social skills. It consists of 25 Likert-type items with three options (0=No, never; 1=Sometimes; 2=Yes, always) which are grouped into five subscales (with five items each): emotional difficulties, behavioural problems, hyperactivity, peer problems and prosocial behaviour. The higher the score, the greater the degree of difficulties, with the exception of the prosocial behaviour subscale, where a higher score refers to better adjustment. Previous studies indicate that the SDQ scores show appropriate psychometric behaviour in Spanish teens.42,43

Trait Meta-Mood Scale-24, TMMS-2444The TMMS-24 is a self-report made up of 24 items distributed in three dimensions (eight items each): perception, understanding and emotional regulation. It allows the assessment of the reflective aspects of emotional experience, within the models of emotional intelligence as a skill. The response format is a five-point Likert-type (1=Completely disagree; 5=Completely agree). Previous studies carried out with young Spaniards indicate that it is an instrument with adequate psychometric performance.45

Interpersonal Reactivity Index, IRI46The IRI was developed to assess empathy from a multidimensional point of view. It consists of 28 items grouped into four dimensions (of eight items each): (a) empathic concern (assesses feelings of affection, compassion and concern towards others); (b) personal discomfort (measures feelings of anxiety and discomfort resulting from observing another person's negative experience); (c) perspective taking (assesses efforts to adopt other people's perspective and see things from their point of view); and (d) fantasy (measures the tendency to identify with characters in films, novels, plays and other fictional situations). The response format is a five-point Likert-type (1=Does not describe me well at all; 5=Describes me perfectly). In the present study, the version of the IRI validated in the Spanish population.47

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale48This tool is a one-dimensional scale for evaluating self-esteem. It consists of 10 items (for example, “in general I am satisfied with myself”) with scores on a Likert-type scale of four points (1=totally disagree; 4=totally agree). In this study we used the Spanish version which presents with the appropriate psychometric properties.49

Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-Short Form, RADS-SF50The RADS-SF is a self-report used for the assessment of the severity of depressive symptomatology (anhedonia, somatic complaints, negative self-evaluation and dysphoria) in teens. It consists of a total of 10 items in a four-choice Likert-type response format (1=Almost never; 4=Almost always). In this study we used the RADS-SF version adapted and validated in Spanish for teens.51

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ-CA)52The ERQ-CA is a self-report measure of emotional regulation consisting of 10 items following a seven-alternative response format (1=Strongly Disagree; 7=Strongly Agree). The ERQ-CA includes two subscales: cognitive reappraisal (six items) and expressive suppression (four items). These two subscales describe two distinct emotional regulation strategies. Cognitive reappraisal would modify emotional reactions as soon as they arose, whilst expressive suppression would only modify emotional expression, trying to hide from the experience involved without altering it. The Spanish ERQ-CA version has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in previous studies.53

The 10-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children54The PANAS for children consists of two factors designed to measure positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). The 10 items have a Likert-type format with responses ranging from 1 (very little or not at all) to 5 (extremely or very much). Five items assess PA through adjectives such as: cheerful, lively, happy, energetic and proud; and five items assess AN: depressed, angry, fearful, scared and sad. The PANAS-C assesses the way people feel and/or behave during the last few weeks. This instrument has demonstrated adequate psychometric quality in previous work with Spanish teens.55

ProcedureThe research was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of La Rioja (CEICLAR). This study is part of the Regional Mental Health Plan of La Rioja 2016–2020.

The administration of the measurement instruments was carried out collectively, in groups of 10–35 students, during school hours, using a computer, and in a classroom equipped for this purpose. The administration of the questionnaires was carried out at all times under the supervision of a trained assistant.

The study was presented to the participants as an investigation into emotional well-being, assuring them of the confidentiality of their answers, as well as the voluntary nature of their participation. Parental consent was also requested from participants under 18 years of age.

Data analysisOverall network estimationThe networks estimated in the present study were weighted and undirected. First, the suicidal behaviour network was estimated from the Paykel Scale items. Second, the psychological network structure of suicidal behaviour (total score), emotional and behavioural difficulties, prosocial behaviour, subjective well-being, emotional intelligence, self-esteem, depressive symptomatology, empathy, positive and negative affect and emotional regulation was estimated. For network estimation and visualisation, the R package Qgraph56 was used. For a more detailed analysis of the network estimation and inference procedures, previous review papers can be consulted.10,57–60

A network is a representation of a set of nodes and edges. The nodes represent the objects or variables under study, while the edges represent the connections between the nodes, i.e. the “line” that connects them. In network analysis in psychopathology, nodes usually represent symptoms (signs, states, traits, etc.) (which are usually assessed by means of measurement instruments), while edges represent the associations between them. The network was designed using an algorithm called Fruchterman-Reingold, which, by means of an iterative procedure, places the most relevant nodes in the centre of the network and the weakest ones in the periphery. When the variables are dichotomous in nature, as for example the items of the Paykel Scale, the Ising Model is used. When the variables are distributed according to multivariate normality, the Graphical Gaussian Model (GGM) is used. These models are based on conditional dependence relationships that are similar to partial correlations. Two nodes are connected in the resulting graph through an edge (they are statistically related) after controlling for the effect of all other variables in the network, i.e. after controlling for spurious correlations that may arise due to multiple comparisons. When they are not connected they are conditionally independent. The EBIC-GLASSO regularisation procedure was used.

Network inferenceIn accordance with previous studies for network analysis, three measures were estimated: strength of centrality (strength), expected influence and predictability.

- •

(a) Strength. This is a measure of centrality that allows us to infer the relative importance of the node in the estimated network. It refers to the magnitude of the association with the other nodes, i.e. which node has the strongest connections. A node with a high centrality in this parameter is a node that influences many other nodes.

- •

(b) Expected influence. This is the sum of all edges of a node. This measure of inference improves some limitations underlying the computation of strength centrality, as the latter uses the sum of the absolute weights (i.e. negative edges become positive edges before summing), which distorts the interpretation of the results if there are negative edges.

- •

(c) Predictability. This is an absolute measure of interconnectedness that provides the explained variance of each node that is explained by all its neighbouring nodes. It is represented in graphs as the dark areas in the circle around the nodes. It can be interpreted similarly to R2 (% of variance explained).

To test the stability and accuracy of the network, the bootnet package of R was used. Given the combination of sample size and number of nodes leading to a considerable computational burden, a bootstrap analysis was performed. Measures of network accuracy and stability allow the estimation of the precision of edges and centrality indices.61

SPSS v2262 and R63 SPSS statistical software were used for the analyses.

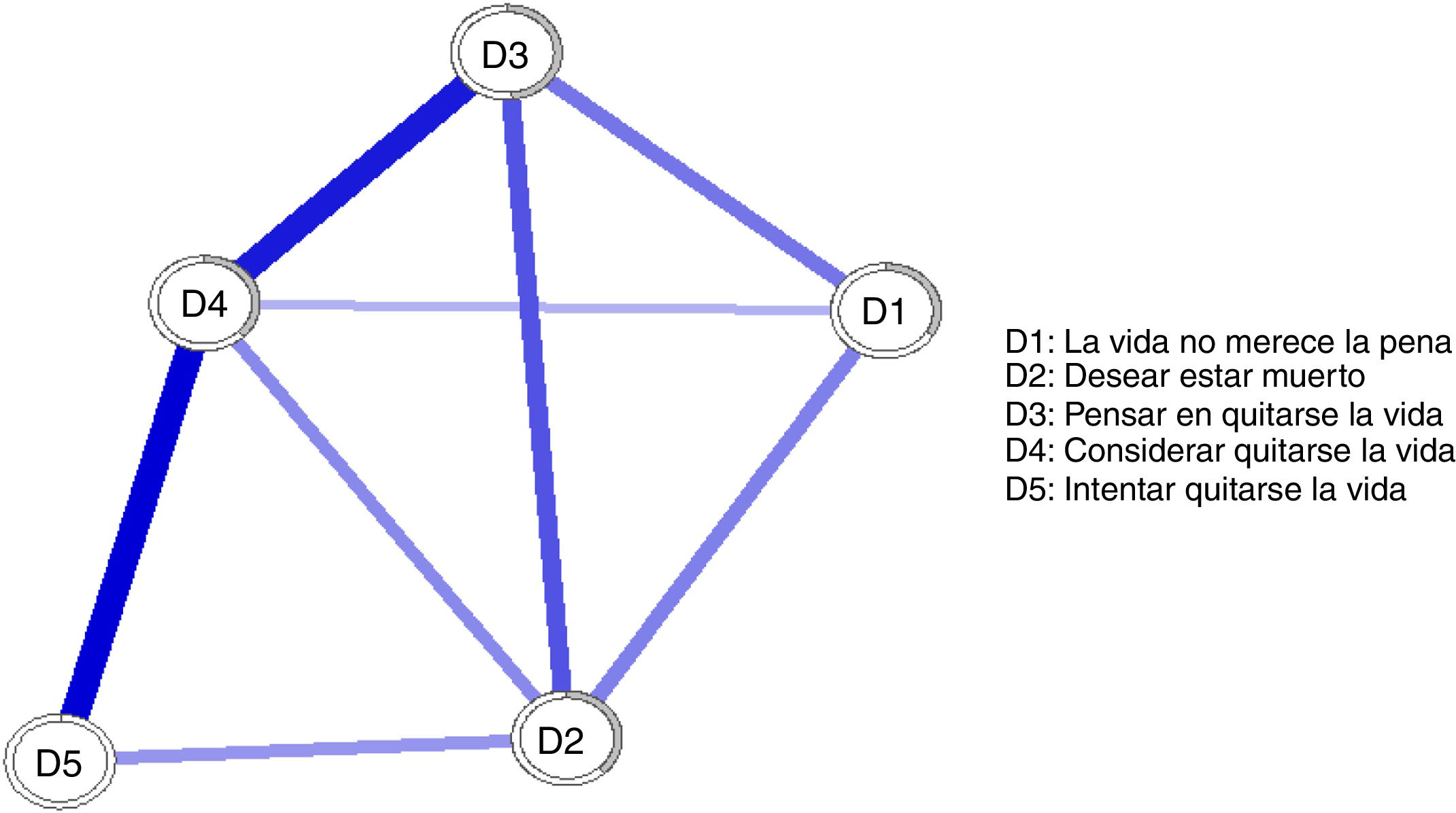

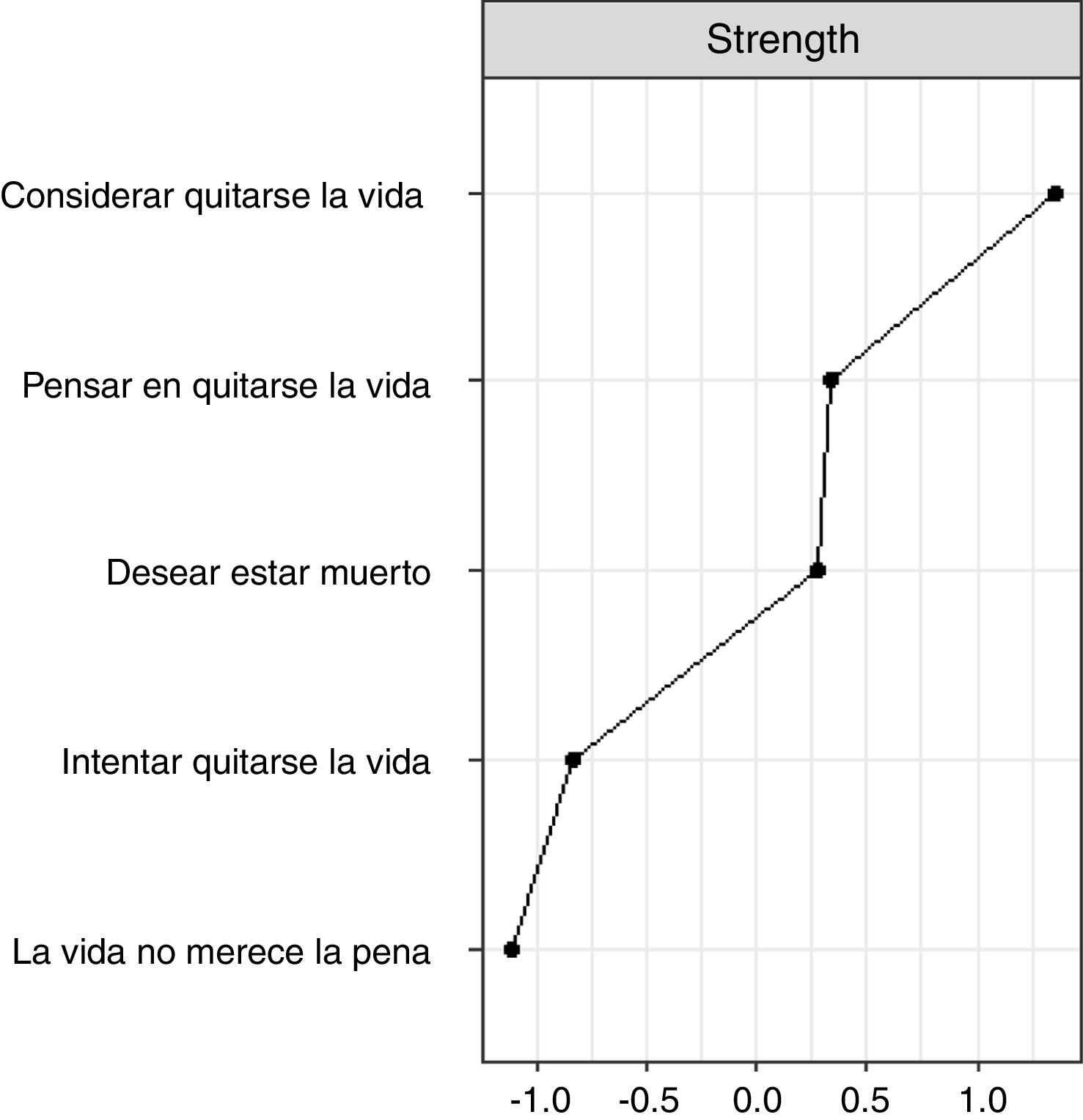

ResultsNetwork structure of suicidal behaviourAs shown in Fig. 1, in the estimated suicidal behaviour network, the psychometric indicators were strongly positively interconnected. Fig. 2 shows the centrality strength values. Since all relationships between the nodes were positive, the expected influence values were identical to the strength centrality values and are therefore not shown. The most central node in the network in terms of expected influence was “considering taking one's own life” (D4). Predictability ranged from 0% (D5, suicide attempt) to 51.7% (D3, thinking about taking one's own life). The average predictability was 33.52%. Noteworthy is node D5, which did not explain any percentage of the variance due to its low prevalence in the present sample (M=.06; SD=.24).

Estimated network of suicidal behaviour in the sample of adolescents. Note: The nodes correspond to the items of the Paykel Suicide Scale. The thicker the line, the greater the relationship between nodes. The blue colour of the line indicates a positive relationship between nodes (items). The circle around the nodes indicates the degree of variance explained for that node as a function of the other nodes in the network.

Centrality strength indices for the items of the Paykel Suicide Scale. Note: Since all relationships between nodes are positive, the centrality strength indices correspond to the expected influence indices in the estimated network of suicidal behaviour. In this sense, the expected influence indices in the figure have been omitted.

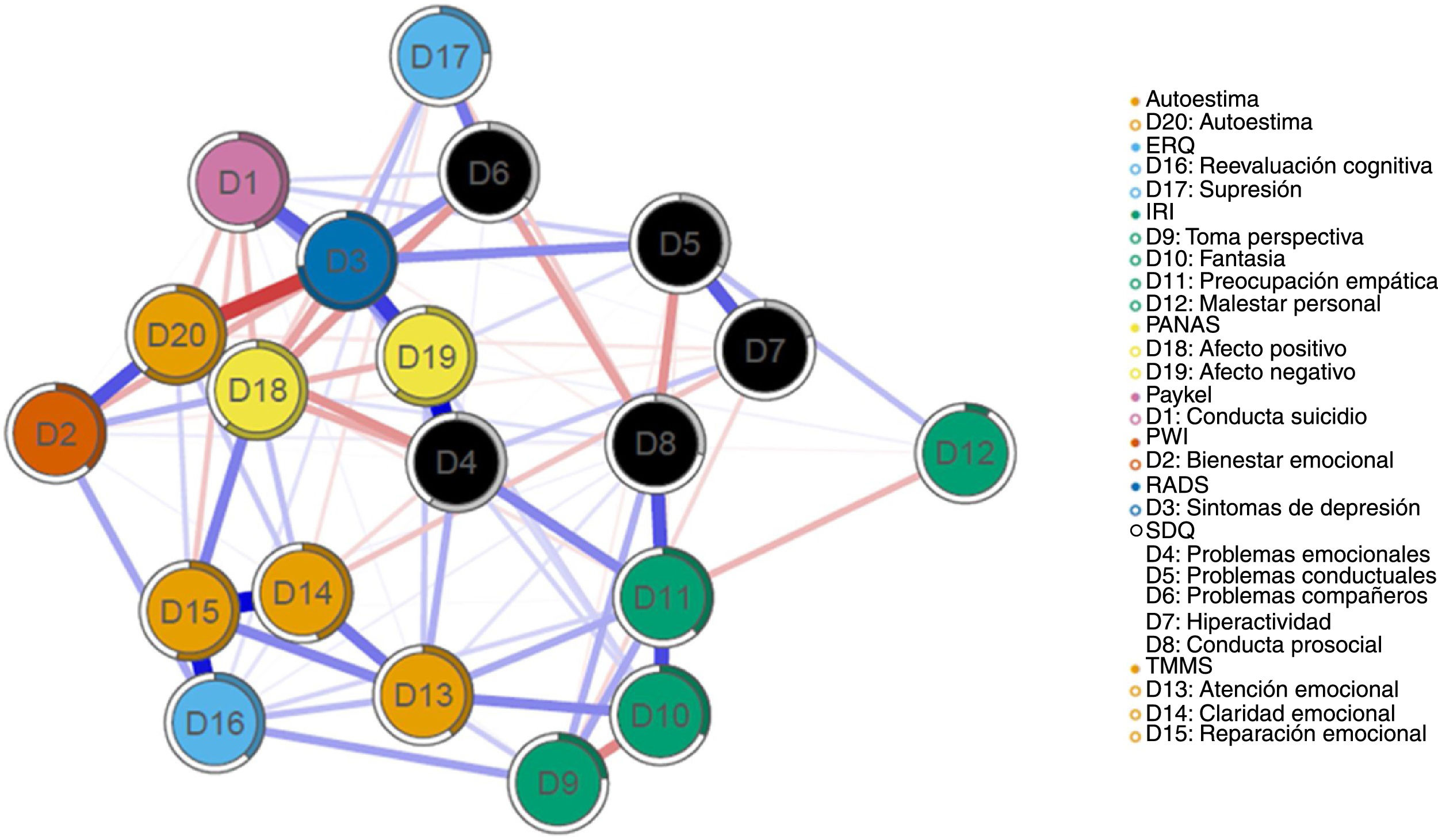

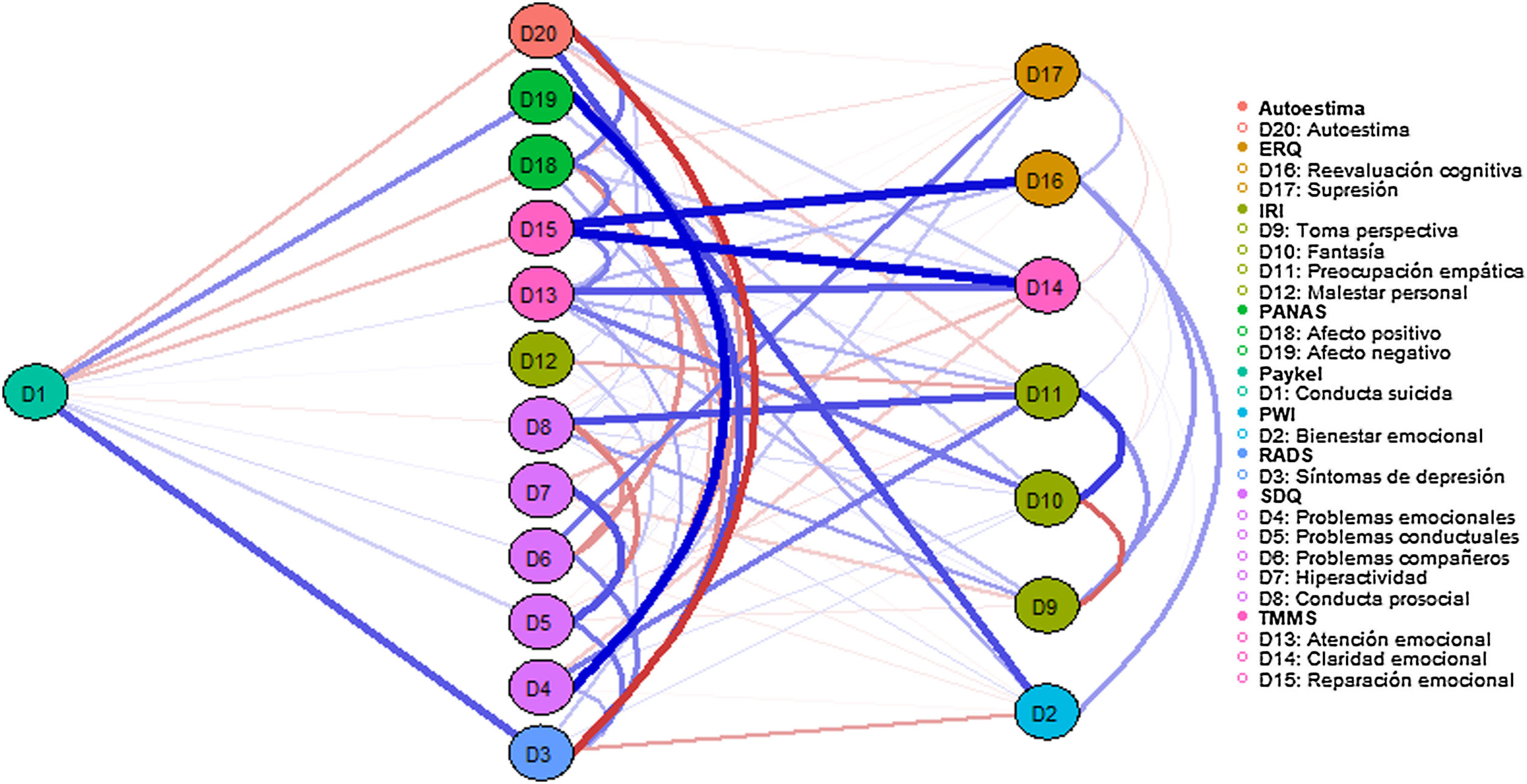

Fig. 3 shows the estimated network for the different indicators of suicidal behaviour, risk and protective factors. Several aspects are noteworthy. First, the estimated network showed strong connections between the nodes that can be considered as protective factors (positive affect, self-esteem, emotional intelligence, prosocial behaviour, etc.). Second, the nodes representing risk factors (emotional problems, negative affect, suicide, depression, etc.) were also strongly positively connected to each other. Third, protective factors, like risk factors, were more closely related to each other (intra-domain level, e.g., SDQ nodes to each other) than to other nodes in the network (inter-domain level, e.g. between TMMS-24 and ERQ scores). Fourth, suicidal behaviour was positively related to depressive symptomatology and negative affect nodes, and negatively related to self-esteem and positive affect.

Estimated psychological network of suicidal behaviour, risk and protective factors in the adolescent sample. Note: The nodes correspond to the tests administered (total score) and/or the subscales (or dimensions). The thicker the line, the greater the relationship between nodes. The blue colour of the line indicates a positive relationship between nodes. The red colour of the line or edge indicates a negative relationship between nodes. The circle around the nodes indicates the degree of variance explained for that node in terms of the other nodes in the network.

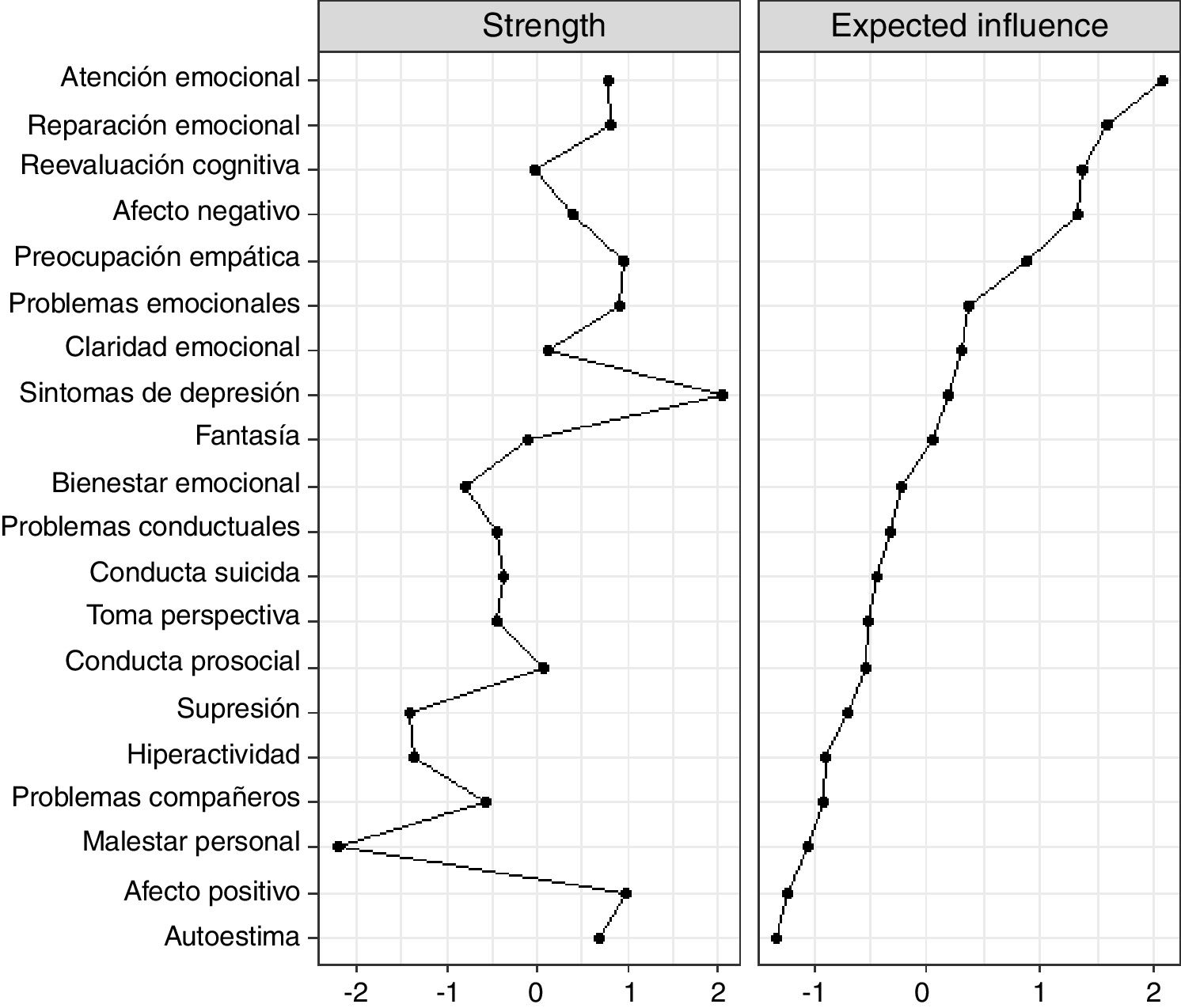

In the estimated psychological network (Fig. 4), the most central nodes in terms of strength were: depressive symptomatology, positive affect and empathic concern. In terms of expected influence, the most influential nodes were perceived emotional intelligence, empathy and affect. Predictability ranged from 10.40% (D12, empathic personal distress) to 74.40% (D3, depressive symptomatology). The average predictability was 39.5%.

In order to further analyse the specific relationship between suicidal behaviour and the different risk and protective factors, a flow diagram was performed. The results are presented in Fig. 5.

Stability and accuracy of the estimated networkThe results of the bootstrap analysis indicated that the network was estimated accurately. The stability analyses of the centrality indices and edge accuracy indicated that the networks were estimated accurately, with moderate confidence intervals around the edge weights. The results are reported in the supplementary material (see Appendix A).

DiscussionThe main purpose of this study was, on the one hand, to analyse the structure of the suicidal behaviour network using the Paykel Scale and, on the other, to examine the psychological network of suicidal behaviour, psychological risk and protective factors in an incidental sample of adolescents. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine both the network structure of suicidal behaviour and its relationship with different cognitive, affective, behavioural and social indicators in adolescents. This study attempts to offer a deeper, or at least different, understanding of suicidal behaviour and its links with mental health and emotional well-being and different domains of socio-emotional adjustment. New psychological approaches, such as the network model, are likely to provide new perspectives in delineating, conceptualising, understanding and addressing suicidal behaviour.13–15

The main findings are discussed in more detail below. First, indicators of suicidal behaviour were strongly connected in the estimated network. In particular, the nodes that were most connected were those referring to greater severity, such as considering taking one's own life and previous attempts. The most central node in the estimated network in the present study in terms of strength and expected influence was “considering taking one's own life”. The average predictability was 33.52%, implying that a substantial percentage of the variability in the network remained unexplained. These results are also consistent with previous studies in the adult population, although the network model has not yet been extensively applied to the study of suicidal behavior.12,64,65 So caution should be exercised in cross-study comparisons and possible generalisations. For example, De Beurs et al.,66 using a sample of 3508 Scottish young adults and a battery of psychological tests, found that: (a) internalizing entrapment contributed most to current suicidal ideation and (b) perceived burden and entrapment were statistically associated with current suicidal ideation, whereas depressive symptoms were associated with past history of suicidal ideation. The results may be consistent with the conceptual view that understands suicidal behaviour as a complex network structure of interacting cognitive, emotional and behavioural traits.

Secondly, the network structure between suicidal behaviour, emotional and behavioural difficulties, prosocial behaviour, subjective well-being, emotional intelligence, self-esteem, depressive symptomatology, empathy, positive and negative affect and emotional regulation was analysed. The variables showed both intra- (e.g., dimensions within a single test, e.g., the SDQ) and inter-domain relationships (between dimensions of different tests, e.g., between the SDQ, the IRI, the RADS and the TMMS-24). It is true that intra-domain connections were generally stronger than inter-domain relationships. In the estimated psychological network, the most central nodes in terms of strength were depressive symptomatology, positive affect and empathic concern. In terms of expected influence, the most influential nodes were those referring to emotional attention and repair (perceived emotional intelligence) and empathic concern. Predictability values ranged from 10.40% for empathic personal distress to 74.4% for depressive symptomatology. The average predictability was 39.5%, which is similar to, but higher than that found in the estimation of the suicidal behaviour network and previous work with other psychological problems.67

Also, suicidal behaviour was positively related to depressive symptomatology and negative affect, and negatively related to self-esteem and positive affect. It is noteworthy that, beyond the point of view of traditional psychopathology, protective factors (e.g., prosocial behaviour, positive affect and subjective well-being) were found to be, on the one hand, more closely associated with each other and, on the other hand, negatively related to variables referring to mental health difficulties or risk factors (e.g., peer problems, emotional symptoms). In this regard, we should not lose sight of the fact that network analysis allows for the analysis of the relationship between domains after controlling for the effect of all other nodes in the network. This aspect is interesting, as it is observed that in the estimated network, for example, the negative association between self-esteem and suicidal behaviour is maintained after controlling for the effect of all other domains. To date, few studies have analysed the suicidal behaviour network using risk and protective factors simultaneously in adolescents, making comparison with previous studies difficult. In a recent study68 conducted in a representative sample of adolescents, it was found that applying network analysis, Paykel scores were positively associated with attenuated psychotic experiences, schizotypal traits, negative affect and emotional difficulties, and negatively associated with positive affect and subjective emotional well-being. Another network analysis study69 in adults found that feeling depressed, overburdened and hopeless were central risk factors for suicide, while self-esteem and social support were central protective factors.69 Overall, this research seems to point to the importance of examining protective factors and risk factors in isolation and in interaction, in order, for example, to understand the dynamic relationships involved in suicidal behaviour, to determine potential suicide risk and/or to establish preventive strategies. For example, findings suggest that interventions aimed at decreasing depressive symptoms or increasing self-esteem and positive affect may be particularly beneficial in reducing suicide risk. Future studies should continue to analyse longitudinally the role of protective factors for suicidal behaviour as key elements in promoting well-being and preventing mental health problems.

The results of this study should be interpreted from a multidimensional, multicausal, dynamic, individual, contextual and phenomenological perspective. A radically biopsychosocial model that takes into account the complex dynamic interaction between biological, psychological and social factors, experienced (lived) by a particular person with a particular biography and circumstances.9,15,70 The network model fits into this view, since it understands psychological problems as dynamic constellations of symptoms that are causally interrelated, i.e. connected through systems of causal relationships.5 Such interactions can occur within the same level of analysis (e.g., at the phenotypic level between symptoms and signs) or between different levels (e.g., between genetic, brain, cognitive, phenotypic levels), i.e. both horizontally and vertically. Moreover, this putative network of symptoms or mental states may oscillate over time, from moment to moment, e.g. if a certain symptom relationship remains activated over a long period of time it could lead to a psychopathological disorder. Also, new interrelationships between symptoms may emerge (activation or deactivation) and/or vary depending on certain conditions of the individual and/or other circumstances (e.g., environmental conditions, stress, prophylactic interventions, etc.).

This study is not without limitations. First, the selection of participants was by incidental sampling, which does not allow for a generalisation of the results to other populations of interest. Second, the use of only self-report information also limits the conclusions drawn from this study. Third, adolescence is a stage of development in which different biopsychosocial changes and transformations are confronted and this must be taken into account for an accurate interpretation of results. Fourth, the study is cross-sectional, so it is not possible to make cause-effect inferences. Fifth, the different psychometric indicators have been considered here as risk or protective factors for suicidal behaviour, however, it is also possible that these variables (e.g., depressive symptoms) can be seen as another domain of psychopathology. Sixth, the structure of the estimated networks is limited by the tool used. Finally, network analysis is currently in its early stages and is not exempt from criticisms.70,71 Although it shows promise as a methodology to help obtain important information in a number of research fields, there are still limitations and unresolved issues (e.g., it has not yet been fully articulated as a scientific network theory for mental disorders).72

Future studies should incorporate network models with information from multiple levels of analysis (e.g., genetic, brain, cognitive, phenomenological, environmental). In addition, it would be highly relevant to collect longitudinal information through new methodologies such as outpatient assessment. Basically, it would be to move beyond the network vs. biomedical model and rotate towards dynamic, contextual and individualised models.

FundingThis research was funded by the Instituto Carlos III, Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), by the Instituto de Estudios Riojanos (IER), by the Ayudas Fundación BBVA a Equipos de Investigación Científica 2017 and co-financed with FEDER funds in the PO FEDER de La Rioja 2014-2020 (SRS 6FRSABC026).

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.