Psycho-COVID: Long-term effects of COVID19 pandemic on brain and mental health

Más datosThe COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown may have an impact in mental health among youth, but reports of psychiatry emergency department encounters in young Spanish population are scarce. The aim of this study is to characterize the reasons for psychiatric urgent care of youth during COVID-19 pandemic in our hospital.

Material and methodsThis cross-sectional study compare visits to the psychiatry emergency department and their characteristics in young patients in the province of Lleida before and after the pandemic with special attention to the two states of alarm and suicidal behavior. Information regarding sociodemographic status, chief complaints, diagnosis, characteristics of suicidal behavior, and other data were obtained from the electronic medical records.

ResultsWithin the total psychiatric emergency attendances, youth patients increased a 83.5% in the second state of alarm (p=0.001). In this period patients were younger (p=0.006), had less psychiatric history (p=0.017) and their living conditions changed with an increase of those living with relatives (p=0.004). Suicidal ideation care increased without statistical significance (p=0.073). Multiple logistic regression identifies independent risk factors for suicidal behavior being female (OR: 2.88 [1.39–5.98]), living with relatives (OR: 3.49 [1.43–8.54]), and having a diagnosis of depression (OR: 6.34 [3.58–11.24]).

ConclusionsThe number of young people seen in psychiatric emergencies during the chronic stage of the pandemic increased, and these were getting younger and without previous psychiatric contact. The trend to higher rates of suicidal ideation indicates that youth experienced elevated distress during these periods, especially women, living with relatives and presenting depression.

El brote de COVID-19 y el confinamiento pueden tener un impacto en la salud mental entre los jóvenes, pero los estudios de visitas al servicio de urgencias de psiquiatría en la población joven española son escasos. El objetivo de este estudio es caracterizar los motivos de atención de urgencia psiquiátrica de los jóvenes durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en nuestro hospital.

Material y métodosEste estudio transversal compara las visitas a urgencias de psiquiatría y sus características en pacientes jóvenes de la provincia de Lleida antes y después de la pandemia, con especial atención a los 2 estados de alarma y la conducta suicida. La información sobre el estatus sociodemográfico, las principales quejas, el diagnóstico, las características de la conducta suicida y otros datos se obtuvieron de la historia clínica electrónica.

ResultadosDentro del total de atenciones de urgencias psiquiátricas, los pacientes jóvenes aumentaron un 83,5% en el segundo estado de alarma (p=0,001). En este período los pacientes eran más jóvenes (p=0,006), tenían menos antecedentes psiquiátricos (p=0,017) y sus condiciones de vida cambiaron, con un aumento de los que vivían con familiares (p=0,004). La atención a la ideación suicida aumentó sin significación estadística (p=0,073). La regresión logística múltiple identifica factores de riesgo independientes para la conducta suicida: ser mujer (OR: 2,88 [1,39-5,98]), vivir con familiares (OR: 3,49 [1,43-8,54]) y tener un diagnóstico de depresión (OR: 6,34 [3,58-11,24]).

ConclusionesAumentó el número de jóvenes atendidos en urgencias psiquiátricas durante la etapa crónica de la pandemia, y estos cada vez eran más jóvenes y sin contacto psiquiátrico previo. La tendencia a tasas más altas de ideación suicida indica que los jóvenes experimentaron una angustia elevada durante estos períodos, especialmente las mujeres, que vivían con familiares y presentaban depresión.

The COVID-19 pandemic is having a psychological impact on individuals. The COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown may have multiple consequences on the lives of adolescents. Social relations are disrupted and the individuals are staying at home. Worry for their families, unexpected bereavements, sudden school break, and home confinement in many countries may contribute to acute and chronic stress modulated by an increased time of access to the Internet and social media.1 It is possible that pre-existing psychosocial vulnerabilities (child victimization, socioeconomic disadvantage, history of psychopathology) amplify the detrimental impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of young people, thus widening the already evident risk inequalities among the population and increasing the complexity of the clinical presentation.2

Suicide attempts are undertaken most frequently by young people, especially by teenage girls and young women. In fact, suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescents between the ages of 15 and 19.3 The ratio of suicide in this age group increased significantly in the last few years. Phenomena which are of special importance for the prevention of suicide among adolescents include suicidal thoughts, attempted suicide, and completed suicide.4 A mainstay in the identification and management of youth at risk for suicide is the use of suicide risk factors, such as past suicide attempts, past or current suicidal ideation, mood disorders, substance use disorders, psychosis, male gender, and lack of family support. A history of at least one medically serious suicide attempt or violent self-harm is a particularly important risk factor.5

Epidemics may be linked to increased suicide rates6 but there are few studies on suicidal behavior in young people in a pandemic situation in Spain.7 It is worth highlighting a study carried out in Catalonia between March 2020 and March 2021, an increase of 25% in suicide attempts in young people was observed, while in adults it decreased by 16.5%. The increase of suicide attempts in girls was especially prominent in the starting school period in the COVID-year (September 2020–March 2021), where the increase reached 195%.8

In short, the COVID 19 pandemic can impact the mental health of the youngest, being a prolonged sequel to the pandemic situation. The objective of this study is to evaluate the impact that the COVID 19 pandemic may have had on the reasons for the urgent care of patients youngest, comparing the reasons for care with those from a previous period and to assess whether there was an increase in suicidal behavior among the youngest.

MethodSample and procedureThis study was carried out at the Santa Maria University Hospital in Lleida, Spain. This hospital is the only one providing urgent psychiatric care in the province of Lleida, with an area of influence of 431,183 people.9

The data in this study were obtained through a retrospective review of digital medical records extracting all the patients visited in the Psychiatric Emergency Department of Santa Maria University Hospital in Lleida. The observation periods were: (1) before confinement: from January 13, 2020, until March 14, 2020, and (2) during the confinement of the first state of alarm in Spain: from its start on the 15th of March, 2020 until its conclusion on the 20th of June, 2020; and the second state of alarm in Spain: from October 25, 2020 to May 9, 2021.10 Patients with less than 18 years of age were selected from the total sample.

MeasurementsThe following information was collected from digital medical records: number of visits to the emergency unit for psychiatric reasons in the periods described, sociodemographic profile of the patients who attended an emergency unit (gender, date of birth and marital status), psychiatric diagnosis (following the criteria in DSM-IV11), chief complaint and referral upon discharge. We used Silverman et al.’s definition for attempted suicide: a self-inflicted, potentially injurious behavior with a nonfatal outcome for which there is evidence (either explicit or implicit) of intent to die.12

The authors state that all the procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 2008.13 This study was approved by the ethics and clinical research committee of Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using the IBM-SPSS v.23 statistical package. Continuous data were expressed as mean±standard deviation while categorical data were presented as percentages. The normal distribution was evaluated using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Chi-square and t-student tests were used for continuous data. As a non-parametric alternative, Fisher's exact test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used, as appropriate. Univariate analyses were performed to explore whether sociodemographic and clinical variables were associated with suicidal behavior. Fisher's exact test (FET) provided the significance and the odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) provided the effect size. The significant variables (p<0.05) in the univariate analyses were included in a stepped bivariate logistic regression model. Type I error was set at the usual value of 5% (alpha=0.05) with a two-sided approximation. Hospital admissions were not included in the regression analysis as it is a consequence of suicidal behavior and not a possible risk factor.

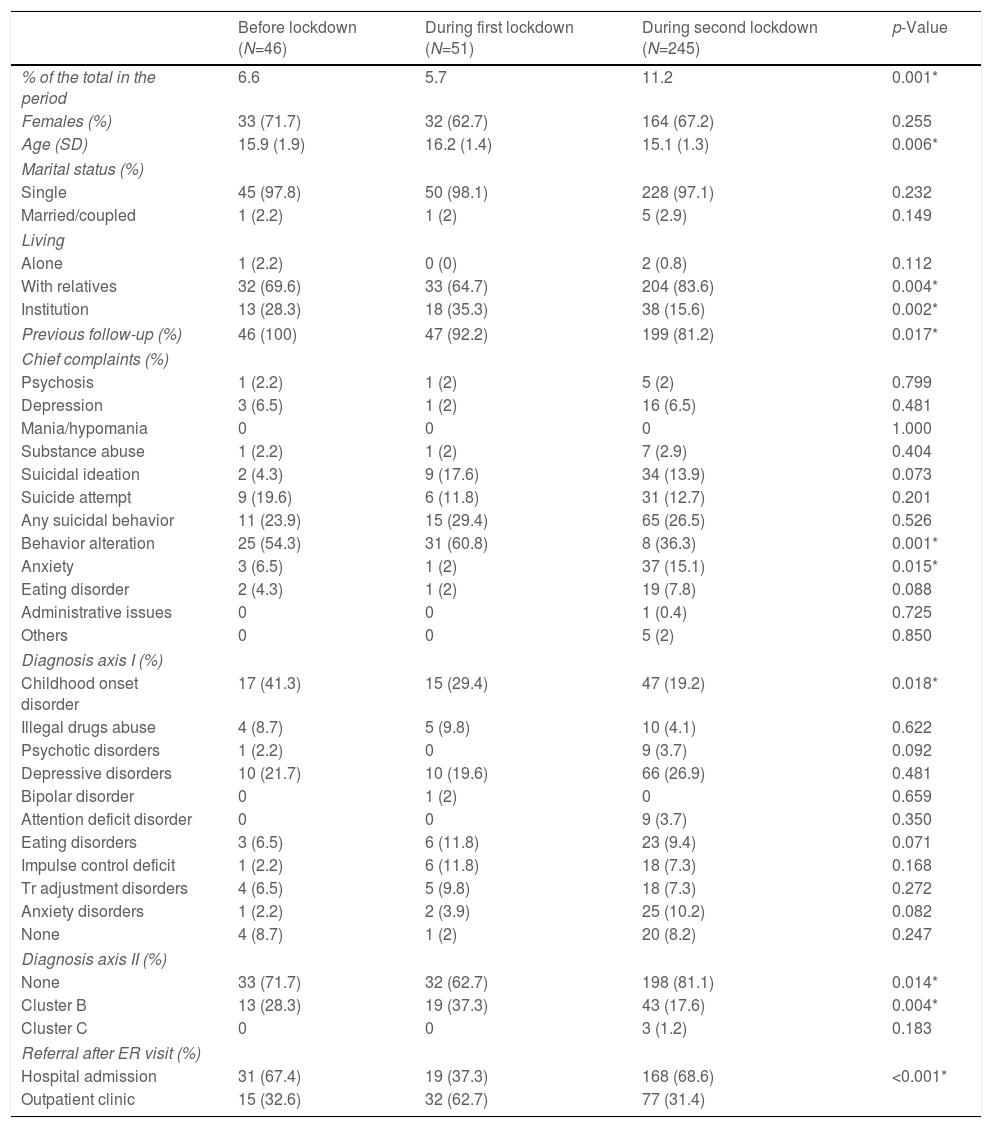

ResultsDescription of the sociodemographic and clinical variables of the sample of young people cared during all periodsWe recruited 342 patients under 18 years of age during the study period, which represents 9% of all psychiatric emergency visits. Most of the significant sociodemographic changes occurred in the second state of alarm (Table 1). During this period, young patients represent 11% of all psychiatric emergency visits, illustrating an 83.5% increase in young visits compared to the two previous periods studied, when only 6.2% of the visits were from young people (p=0.001). In this period, we found a decrease in age (p=0.006), a greater proportion of patients who lived with relatives (p=0.004) and a lower proportion of institutionalized patients (p=0.002). We also found more patients without prior follow-up in the second state of alarm (p=0.017). Regarding the chief complaints, we found a decrease in behavioral disturbance (p=0.001) and an increase in anxious decompensation (p=0.015) in the second state of alarm. Suicidal ideation increased during the two states of alarm without reaching statistical significance (p=0.073). Regarding diagnoses, we found a decrease in childhood-onset disorders in both states of alarm (p=0.018), a decrease in patients without diagnosis of axis II in the first state of alarm (p=0.014) and a decrease of cluster B diagnoses in the second state of alarm (p=0.004) without significant variations in the rest of the diagnoses. Discharge referral was significantly modified with a decrease in hospital admissions in the first state of alarm (p<0.001).

Visits to the HUSM psychiatry emergency department of patients under 18 years of age during the pandemic.

| Before lockdown (N=46) | During first lockdown (N=51) | During second lockdown (N=245) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of the total in the period | 6.6 | 5.7 | 11.2 | 0.001* |

| Females (%) | 33 (71.7) | 32 (62.7) | 164 (67.2) | 0.255 |

| Age (SD) | 15.9 (1.9) | 16.2 (1.4) | 15.1 (1.3) | 0.006* |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Single | 45 (97.8) | 50 (98.1) | 228 (97.1) | 0.232 |

| Married/coupled | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2) | 5 (2.9) | 0.149 |

| Living | ||||

| Alone | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.8) | 0.112 |

| With relatives | 32 (69.6) | 33 (64.7) | 204 (83.6) | 0.004* |

| Institution | 13 (28.3) | 18 (35.3) | 38 (15.6) | 0.002* |

| Previous follow-up (%) | 46 (100) | 47 (92.2) | 199 (81.2) | 0.017* |

| Chief complaints (%) | ||||

| Psychosis | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2) | 5 (2) | 0.799 |

| Depression | 3 (6.5) | 1 (2) | 16 (6.5) | 0.481 |

| Mania/hypomania | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Substance abuse | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2) | 7 (2.9) | 0.404 |

| Suicidal ideation | 2 (4.3) | 9 (17.6) | 34 (13.9) | 0.073 |

| Suicide attempt | 9 (19.6) | 6 (11.8) | 31 (12.7) | 0.201 |

| Any suicidal behavior | 11 (23.9) | 15 (29.4) | 65 (26.5) | 0.526 |

| Behavior alteration | 25 (54.3) | 31 (60.8) | 8 (36.3) | 0.001* |

| Anxiety | 3 (6.5) | 1 (2) | 37 (15.1) | 0.015* |

| Eating disorder | 2 (4.3) | 1 (2) | 19 (7.8) | 0.088 |

| Administrative issues | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0.725 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 5 (2) | 0.850 |

| Diagnosis axis I (%) | ||||

| Childhood onset disorder | 17 (41.3) | 15 (29.4) | 47 (19.2) | 0.018* |

| Illegal drugs abuse | 4 (8.7) | 5 (9.8) | 10 (4.1) | 0.622 |

| Psychotic disorders | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 9 (3.7) | 0.092 |

| Depressive disorders | 10 (21.7) | 10 (19.6) | 66 (26.9) | 0.481 |

| Bipolar disorder | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.659 |

| Attention deficit disorder | 0 | 0 | 9 (3.7) | 0.350 |

| Eating disorders | 3 (6.5) | 6 (11.8) | 23 (9.4) | 0.071 |

| Impulse control deficit | 1 (2.2) | 6 (11.8) | 18 (7.3) | 0.168 |

| Tr adjustment disorders | 4 (6.5) | 5 (9.8) | 18 (7.3) | 0.272 |

| Anxiety disorders | 1 (2.2) | 2 (3.9) | 25 (10.2) | 0.082 |

| None | 4 (8.7) | 1 (2) | 20 (8.2) | 0.247 |

| Diagnosis axis II (%) | ||||

| None | 33 (71.7) | 32 (62.7) | 198 (81.1) | 0.014* |

| Cluster B | 13 (28.3) | 19 (37.3) | 43 (17.6) | 0.004* |

| Cluster C | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.2) | 0.183 |

| Referral after ER visit (%) | ||||

| Hospital admission | 31 (67.4) | 19 (37.3) | 168 (68.6) | <0.001* |

| Outpatient clinic | 15 (32.6) | 32 (62.7) | 77 (31.4) | |

* p<0.05.

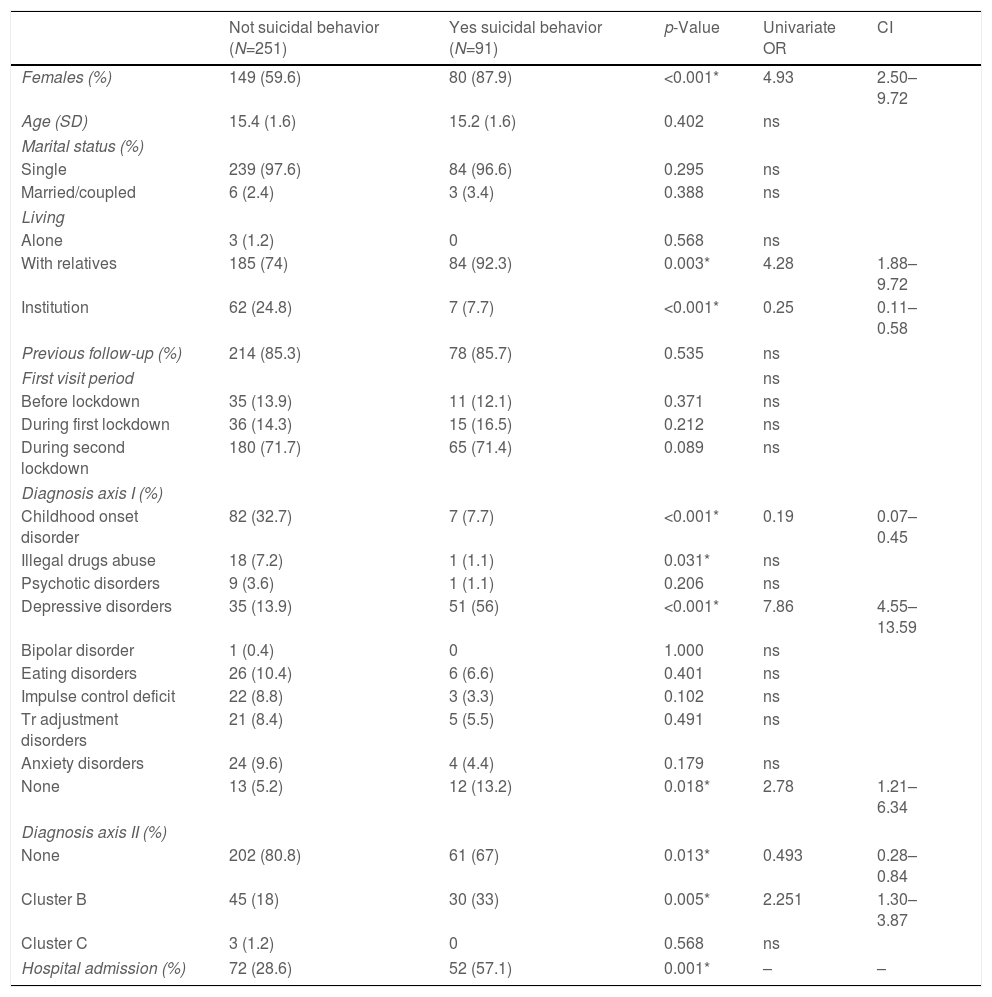

Of all the patients recruited, 91 (26.6%) presented some type of suicidal behavior (45 suicidal ideation, 46 suicide attempt). When comparing suicidal patients with the rest of the patients (Table 2), we found a higher proportion of women (p<0.001), a higher proportion of patients who lived with relatives (p=0.003) and an increase in diagnoses of depression (p<0.001), no diagnosis on axis I (p=0.018) and Cluster B diagnoses (p=0.005). In contrast, in this group there was a lower proportion of institutionalized patients (p<0.001), they had fewer diagnoses of childhood onset disorder (p<0.001) and SUD (p=0.031) and there was a lower proportion of patients without diagnosis of axis II (p=0.013). The rest of the characteristics did not show significant differences between both groups. Finally, we found a higher proportion of hospital admissions after the emergency room visit in patients with suicidal behavior (p=0.001).

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression in patients under 18 years of age with suicidal behavior.

| Not suicidal behavior (N=251) | Yes suicidal behavior (N=91) | p-Value | Univariate OR | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (%) | 149 (59.6) | 80 (87.9) | <0.001* | 4.93 | 2.50–9.72 |

| Age (SD) | 15.4 (1.6) | 15.2 (1.6) | 0.402 | ns | |

| Marital status (%) | |||||

| Single | 239 (97.6) | 84 (96.6) | 0.295 | ns | |

| Married/coupled | 6 (2.4) | 3 (3.4) | 0.388 | ns | |

| Living | |||||

| Alone | 3 (1.2) | 0 | 0.568 | ns | |

| With relatives | 185 (74) | 84 (92.3) | 0.003* | 4.28 | 1.88–9.72 |

| Institution | 62 (24.8) | 7 (7.7) | <0.001* | 0.25 | 0.11–0.58 |

| Previous follow-up (%) | 214 (85.3) | 78 (85.7) | 0.535 | ns | |

| First visit period | ns | ||||

| Before lockdown | 35 (13.9) | 11 (12.1) | 0.371 | ns | |

| During first lockdown | 36 (14.3) | 15 (16.5) | 0.212 | ns | |

| During second lockdown | 180 (71.7) | 65 (71.4) | 0.089 | ns | |

| Diagnosis axis I (%) | |||||

| Childhood onset disorder | 82 (32.7) | 7 (7.7) | <0.001* | 0.19 | 0.07–0.45 |

| Illegal drugs abuse | 18 (7.2) | 1 (1.1) | 0.031* | ns | |

| Psychotic disorders | 9 (3.6) | 1 (1.1) | 0.206 | ns | |

| Depressive disorders | 35 (13.9) | 51 (56) | <0.001* | 7.86 | 4.55–13.59 |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1.000 | ns | |

| Eating disorders | 26 (10.4) | 6 (6.6) | 0.401 | ns | |

| Impulse control deficit | 22 (8.8) | 3 (3.3) | 0.102 | ns | |

| Tr adjustment disorders | 21 (8.4) | 5 (5.5) | 0.491 | ns | |

| Anxiety disorders | 24 (9.6) | 4 (4.4) | 0.179 | ns | |

| None | 13 (5.2) | 12 (13.2) | 0.018* | 2.78 | 1.21–6.34 |

| Diagnosis axis II (%) | |||||

| None | 202 (80.8) | 61 (67) | 0.013* | 0.493 | 0.28–0.84 |

| Cluster B | 45 (18) | 30 (33) | 0.005* | 2.251 | 1.30–3.87 |

| Cluster C | 3 (1.2) | 0 | 0.568 | ns | |

| Hospital admission (%) | 72 (28.6) | 52 (57.1) | 0.001* | – | – |

| Forward stepwise logistic regression model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Wald X2a | p-Value | OR corrected | CI | |

| First step | Depressive disorders | 54.43 | <0.001* | 7.83 | 4.53–13.53 |

| Second step | Female | 10.79 | 0.001 | 3.31 | 1.62–6.77 |

| Depressive disorders | 40.96 | <0.001* | 6.26 | 3.57–0.97 | |

| Third step | Female | 8.16 | 0.004 | 2.88 | 1.39–5.98 |

| Living with relatives | 7.56 | 0.006 | 3.49 | 1.43–8.54 | |

| Depressive disorders | 40.11 | <0.001* | 6.34 | 3.58–11.24 | |

In bivariate logistic regression, the following characteristics were associated with suicidal behavior in those under 18 years of age: being female, living with relatives or in an institution, having a diagnosis of Childhood Onset Disorder, not having a diagnosis on axis I, not having a diagnosis in axis II and having a diagnosis in Cluster B. When analyzing the characteristics in the multiple logistic regression by forward steps, they survived as independent risk factors for suicidal behavior in those under 18 years of age being a woman (OR: 2.88 [1.39–5.98]), living with relatives (OR: 3.49 [1.43–8.54]), and having a diagnosis of depression (OR: 6.34 [3.58–11.24]).

DiscussionThis study shows higher changes in child and adolescent visits to the Psychiatry Emergency Department during the second state of alarm in Spain, suggesting a long-term effect of COVID19 pandemic in this vulnerable population. We found an increase in the psychiatric visits of young patients in the second state of alarm. In this period patients were younger, had less psychiatric history and their living conditions changed with an increase of those living with relatives and a decrease of institutionalized patients. Furthermore, we found a change in the clinical picture of the second state of alarm with more anxious decompensations and less behavioral disturbances in the chief complain and less patients with cluster B disorder in axis II, all in the second state of alarm. In axis I we found a decrease in childhood-onset disorders in both states of alarm. Analyzing suicidality, we found a trend to higher rates in both states of alarm with no statistical significance. Having a diagnosis of depression, live with relatives and being a woman were independent risk factor for suicidal behavior in our sample.

Our observations of an increase of young people visited in psychiatry emergency department with younger age and no previous psychiatric history, are consistent with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention data.14 They showed that mental health related visits in 2020 increased by 24% in ages 5–11 and 31% in ages 12–17 when compared to 2019 data.15 A preliminary review already warned that depressive and anxiety symptoms would increase in children and adolescents.15 Our results showed a change in the chief of complain with an increase in the of young people due to anxiety symptoms and a decrease in personality disorders and behavioral alterations. These results are consistent with those found in preliminary studies from Asia where a cross-sectional survey of 1784 primary school children (77% of 2330 surveyed) from Wuhan and Huangshi after 30 days of home confinement showed that symptom rates depression and anxiety were elevated compared to previous surveys.16 Other preliminary studies supported the emergence of anxiety and depression symptoms through another cross-sectional survey of 8079 middle and high school students (99% of 8140 respondents) from 21 provinces and autonomous regions, again showing high rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms. We did not find significant associations with regard to gender, but some authors have associated higher levels of anxiety and depression with young women.17

Young people in our study population were admitted to the hospital in a lower proportion during the first lockdown. The bibliography in this regard is limited without being able to establish the repercussion in the field of hospitalization.18 This aspect is probably related to the decrease in the total number of available beds, the imposition of greater restrictions on admission and the reduction in the duration of admission.19

In our study, we observed that patients who lived with relatives attended the emergency department more, especially during the second state of alarm. The literature is ambiguous on this. On the one hand, it is pointed out that the fact of having relatives and perceiving their proximity is a factor related to greater resilience to withstand the pandemic.20,21 In fact, some authors reported that children who were isolated or quarantined during pandemic illnesses were more likely to develop acute stress disorder, adjustment and bereavement disorder. 30% of the children who were isolated or quarantined met the clinical criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder.22 But, on the other hand, a novel study conducted in Canada on the psychological impact of the pandemic on families revealed that the majority experienced symptoms of anxiety above the threshold, depression and family dysfunction.23 Another Australian study also warned of far-reaching detrimental family impacts associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.24 Although we have not shown an increase in institutionalized adolescents or those at risk of social exclusion, some authors have pointed out the special vulnerability of specific groups.25

In our sample, both in the first and in the second state of alarm, visits to psychiatric emergencies due to suicidal ideation increased but no statistical significance was reached. Other studies have already shown that there was an increase in young patients who tested positive for suicidality and suicide risk.26 It is relevant to pay close attention to suicidal ideation in younger patients since the existing literature has not been able to accurately approximate the longitudinal trajectory of suicidal ideation in the young population.27 However, existing research indicates that suicidal ideation in adolescents is strongly related to age, with ideation increasing during early adolescence, with an average age of onset between 10 and 15 years.28

When we specifically analyze the young people who consulted for suicidal behavior, we observed that, after logistic regression, it was associated with being a woman, living with relatives and presenting a history of depression. Existing literature suggests that the prevalence rate of suicidal ideation varies by sex, so that more young women, compared to young men, experience more suicidal ideation during adolescence.28 However, it is young boys who are most likely to commit suicide.29 Despite this knowledge, there is little research examining the nature of these gender differences. Family functioning has also been identified as important to consider when quantifying the risk of suicidal ideation in this age group. Family dysfunction has been consistently correlated with suicidal ideation30 and many findings suggest that youth exposed to adverse, dysfunctional, or abusive home environments are at significantly increased risk of subsequent suicidal behavior, including suicidal ideation.31 As in our results, there are previous studies that indicate depression as a risk predictor of suicide attempt in adolescents who report suicidal ideation.28 In our study, the young people who attended due to suicidal behavior were admitted more to the psychiatric unit, this aspect being a consequence of the behavior referred to. There are not many studies on hospitalizations for suicide attempt during the pandemic, but a recent French study revealed that hospitalizations for suicidal behavior in adults in France decreased during 2020.32

Strengths and limitationsThese results must be interpreted with some limitations in mind. First, the data presented here come from the digital medical records and, we have relied on the clinical diagnosis made by different psychiatrists. However, as this is a single-center study, there is a common clinical criterion among all psychiatrists working in our emergency department supporting internal validity of the results. Second, we did not employ validated symptom severity measures but “hospital admission” was used as a logical measure of illness severity. This real-world measure increases the clinical transferability of our results, but they may be affected by hospital logistics during the pandemic. Third, this sample is representative of a population seeking secondary care services and results may not be generalizable to patients seeking primary care services. Fourth, the observed two-month pre-pandemic period may turn out to be short despite being representative of the pre-pandemic situation. Finally, this is a cross-sectional study based on a single center emergency department and causal inference cannot be made. Therefore, prospective studies would be interesting. As a strength of the study, we have been able to obtain a sample that represents all the psychiatric emergencies dealt with in the province, related to youngsters and children, during the two states of alarm.

ConclusionsOur findings highlight a long-term impact on child and adolescent mental health showing a change in the clinical picture of the population visited in the second state of alarm at the psychiatric emergency department. We see an increase of the visits of this population, getting younger and with les psychiatry history. Regarding care for suicidal behavior, these were associated with being a woman, living with relatives and presenting depression. Altogether, our findings call for the public health system and stakeholders to implement durable measures in youngsters focused on prevention, promotion and care during COVID-19 times.

Ethical disclosuresThe authors affirm that all the procedures that contribute to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, revised in 2008. This work was evaluated and approved by the Commission of Ethics and Clinical Research of the Arnau de Vilanova University Hospital.

Conflict of interestAll authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in relation to the performance of this work.