This article presents a verification of the factor structure and validation of the Questionnaire of Achievement of Developmental Task (QADT), designed to measure children's social expectations in early childhood. Three tasks, important from the point of view of both children's functioning at a given life stage and preparation for the next developmental phase, were selected. These are school skills, cooperation with others and a sense of competence. The research aimed to verify the tool's psychometric validity and establish relationships between developmental tasks and indicators of children's mental health.

MethodThe study was conducted in primary school's 4th, 5th and 6th grades (N = 453). The QADT, Brief Multidimensional Students' Life Satisfaction Scale and Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children were used.

ResultsThe tool shows sufficient validity and reliability. The hypothesis regarding associations between the level of developmental task completion and life satisfaction and depressive symptoms was also confirmed.

ConclusionsThe QADT tool can be used in scientific research. This work contributes to the growing body of literature on factors influencing children's mental health and underscores the importance of measuring social expectations of children in early childhood. It also highlights the need to consider developmental tasks in clinical practice and interventions to improve children's mental health. Ultimately, the findings of this study can inform the development of effective preventive and intervention strategies to promote children's mental health and well-being.

Many developmental theories indicate that there are specific tasks or milestones that an individual must complete (achieve) in the life cycle for development to proceed (Berk, 2017). Developmental tasks change during developmental phases and may vary according to culture, gender and historical period. Success or failure in one developmental task can have serious consequences for success or difficulty in meeting other social expectations and developing later problems and disorders (Kellam & Rebok, 1992; Masten et al., 2006; Grzegorzewska, 2015).

The time of middle childhood, the period between the ages of 6 and 12, is a key developmental phase for a child's mental health. During this time, the child develops social, emotional and cognitive skills essential for future success. One important factor influencing the development of these skills is the completion of developmental tasks. During this time, children become increasingly independent, establish new social relationships, experience many, sometimes difficult emotions and develop their interests. Among this period's most important developmental tasks are the acquisition of school skills, the establishment and maintenance of satisfying peer relationships and a sense of competence (Havighurst, 1948/1981).

Difficulties with these tasks can lead to a variety of negative consequences for the child's mental health, both during this period and later. The relationship between school achievement and mental health is bidirectional. On the one hand, school skills in middle childhood and related educational achievement predict educational success in adolescence (Williams et al., 2022) and mental health and disorders in adulthood (Feinstein & Bynner, 2004). On the other hand, children's mental health affects their behaviour at school, and children with emotional and behavioural problems have more significant learning difficulties (Carroll & Houghton, 2007; Fergusson et al., 2008).

Research shows that children who have difficulty making friends may experience feelings of isolation, loneliness and depression, which is associated with reduced self-esteem and psychopathological symptoms in adulthood (Bagwell et al., 1998). In addition, children who fail to cope with learning independence and have a low sense of their own competence may feel low self-worth and experience feelings of hopelessness (Clark & Logan, 2000). Research also suggests that difficulties with developmental tasks during middle childhood can lead to emotional and behavioural disorders (Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Repetti et al., 2002). For example, it has been shown that children who had difficulties with an emotional self-regulation task were more likely to develop emotional and behavioural disorders in the future (Shields & Cicchetti, 1997). Also, difficulties in completing developmental tasks due to frequent moves and changes in the school environment increase the risk of poor achievement, behavioural problems, grade repetition and dropping out of high school (Cutuli et al., 2013; DiStefano et al., 2021; Herbers et al., 2013). These studies point to the important role of developmental task completion during middle childhood in preventing emotional and behavioural disorders (Kellam & Rebok, 1992; Weisz et al., 2005).

Existing research focuses on measuring single selected developmental tasks, such as peer relations or school achievement. The Questionnaire of Achievement of Developmental Tasks (QADT) is an attempt at consolidating the measurement of developmental tasks, giving the possibility of a more comprehensive approach to this issue. A tool for the multidimensional assessment of developmental tasks of middle childhood will allow for a more holistic approach to children's functioning according to the perspective of developmental psychopathology.

The current studyThis research aims to present the validation process of the Questionnaire of Achievement of Developmental Tasks and establish the relationship between middle childhood developmental task realisation and selected indicators of children's mental health. Two indicators relevant to developmental psychopathology were chosen, i.e., sense of life satisfaction and depressive symptom intensity (Grzegorzewska, 2015; Grzegorzewska & Farnicka, 2013; Masten & Coatsworth, 1998; Panayiotou & Humphrey, 2018). Answers were sought to the main questions: (1) Does the QADT have sufficient psychometric properties for measuring developmental task fulfilment? and (2) Are there relationships between developmental task completion, life satisfaction, and depression in school-aged children? Based on previous research, the hypothesis was that the better the level of developmental task completion in middle childhood, the higher the level of life satisfaction in children and the lower the level of depressive symptoms.

MethodProcedureThe study presented here was conducted according to the procedure of the correlation model, ex post facto. In order to validate the developmental task level tool, three measurements were taken at an interval of one year. A 1-year longitudinal cross-lag design was conducted, with repeated measurement (times marked as T1, T2 & T3 respectively). Variables verifying the associations of task completion level with satisfaction and intensity of depressive symptoms were measured at one time point (T3). The project was approved for research on 11.09.2018. by the Scientific Council of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Gdańsk and by the Institute of Psychology of the University of Zielona Góra (approval number 2/2018).

ParticipantsThe study group included 453 subjects: 207 boys and 246 girls aged between 10 and 12 years of primary school grades 4–6. Children from grade 4 (81 boys and 101 girls), grade 5 (53 boys and 37 girls) and grade 6 (73 boys and 108 girls) were invited to participate in the study. The difference in age by gender was statistically significant (F(1, 1355) = 11.572, p < .001) in favour of the girls' results (from d = 0.14 to d = 0.21 in consecutive measurements).

There were no duplicate responses in the collected data, and the total score decreased after the first examination by approximately 0.75 points (F(1, 1355) = 18.5, p < .001, dmale = 0.26, dfemale = 0.28). There was no interaction effect between decreasing scores and gender (F(1, 1355) = 0.11, p = .745).

MeasurementThe following research tools were used in the measurement.

Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS; Seligson et al., 2003). The BMSLSS is a five-item self-report measure developed to assess children's satisfaction concerning the areas of life most pertinent during youth development. Specifically, students are instructed to rate their satisfaction with their family life, friendships, school experiences, self, and living environment. Response options are on a 7-point scale that ranges from 1 – terrible to 7 – delighted. Coefficient α for the total score (the sum of respondents’ ratings across the five items) has been reported at 0.75 to 0.81.

The intensity of depressive symptoms – the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES-DC; Weissman & Orvaschell, 1980) was used. The CES-DC scale contains 20 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (from 0 - never to 3 - always) to assess a child's experience of depressive symptoms over the past week. The CES-DC is based on the adult version, which has been adapted and validated in Poland (Jankowski, 2016). Good psychometric properties characterise the CES-DC scale – the α-Cronbach reliability coefficient is 0.87.

The basis for The QADT (Grzegorzewska, 2006) questionnaire is Havighurst's concept of developmental tasks, according to which developmental tasks are goals set for an individual during a given developmental period to develop and improve knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. The first step in creating the questionnaire was to select the three most important developmental tasks from the point of view of the child's functioning. The next stage was to generate 50 items and assess them by three competent judges to determine theoretical relevance. The initial version of the tool, approved by the judges, was then administered for empirical verification. The results of the study, conducted with 120 children aged 8 to 12 years, showed satisfactory reliability for most scales (α-Cronbach's > 0.77) and allowed the removal of an item that reduced the psychometric value of the tool (Grzegorzewska, 2006). The work in stages I and II resulted in the final version of the tool, consisting of 12 items. Finally, the QADT is a tool consisting of three scales that assess the performance of the following basic developmental tasks of school-age children: academic skills, social cooperation, and sense of competence. The questionnaires consist of 12 items with two alternative responses for each item, with the subject choosing the response that best fits him or her. The psychometric properties presented in this paper represent stage III of the research conducted on the target group in a longitudinal study design.

Statistical analysisReliability, defined as the consistency of the QADT scale in the current study, was estimated by determining McDonald's omega coefficients. Reliability, defined as stability using the ICC index between three measurements of the same individuals one year apart (times T1-T3), was examined.

First, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted on the results of the first measure (T1) to assess construct validity. Then, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the results of the second measure (T2). In line with theoretical assumptions, a three-factor model with three scales was estimated: school skills, sense of competence, and social cooperation. In addition, to test the relevance of extracting the subscales of the tool, a 1-factor model (without extracting the subscales of the tool) was estimated and compared with models including the subscales. CFI and TLI above 0.90, RMSEA and SRMR below 0.08 were assumed to indicate a satisfactory fit of the postulated models to the data. Due to deviations from the multivariate normality of the distribution, the correction proposed by Satorra-Bentler (2010) was applied.

The convergent accuracy rates of the QADT scale were also analysed. Convergent accuracy was calculated by estimating average variance (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) values. It is conventionally accepted that an AVE value above 0.5 and a CR value above 0.8 indicate convergent accuracy (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). On the other hand, discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the AVE of a latent variable with the maximum shared variance (MSV) (the greatest value of the square of the correlation of a latent variable with another latent variable). The discriminant accuracy of a construct is confirmed when the AVE value is higher than the MSV (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Transparency and opennessAll data, analysis code, and research materials are available at https://osf.io/6vqp3/. Data were analysed using R, version 4.2.2 (R Core Team, 2020) and the package lavaan, version 0.6 (Rosseel, 2012) and package psych, version 2.3.3 (Revelle, 2023). This study's design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Psychometric properties of scaleReliabilityThe reliability of the QADT scale was estimated based on the value of McDonald's omega coefficient due to the assumed three-factor structure of the results. Values ranging from ωt = 0.81 for T1, through ωt = 0.84 for T2, to ωt = 0.87 for T3 were found.

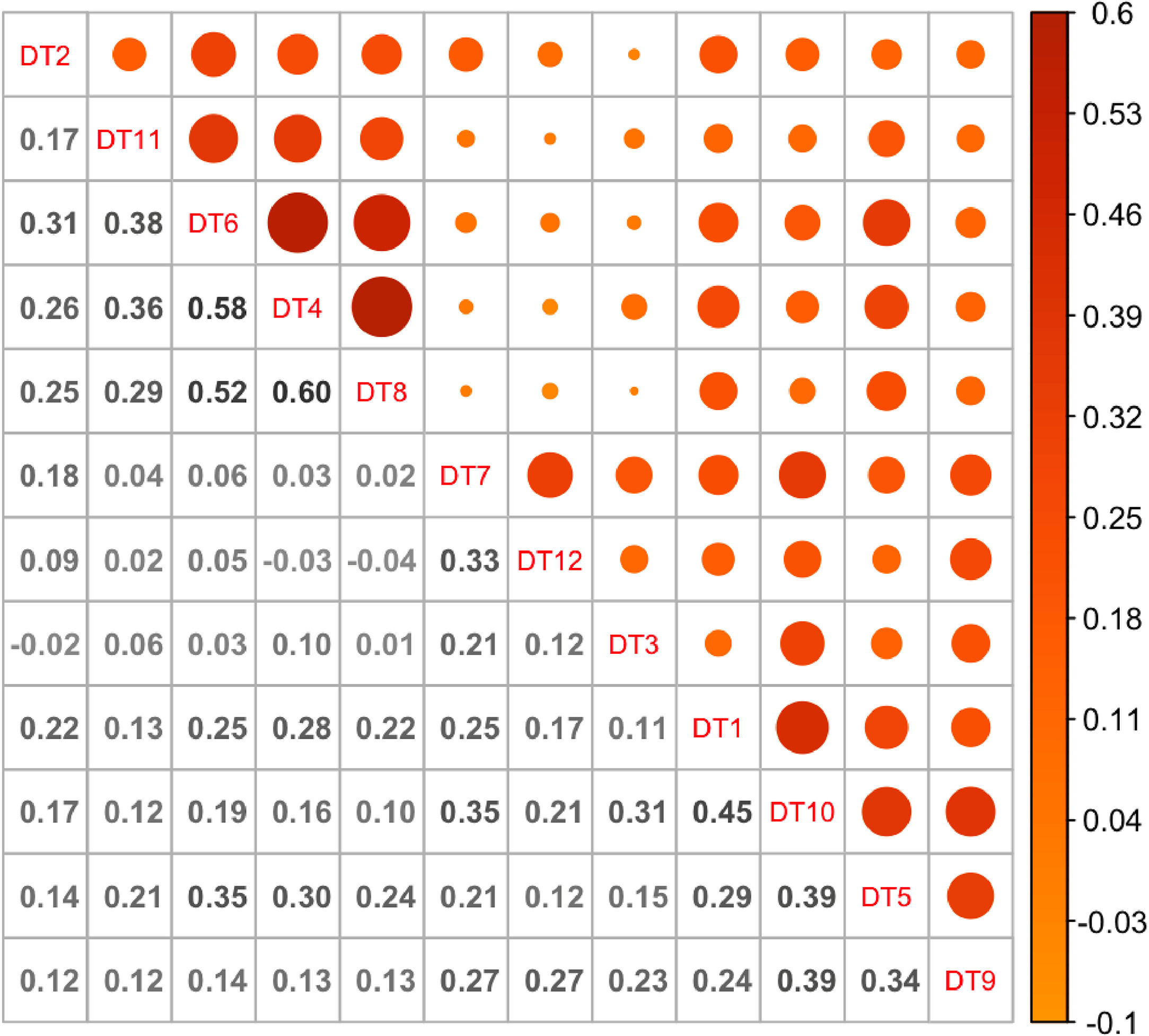

Analysis of the inter-relationships between the items indicates the existence of two clusters of responses to QADT items (see Fig. 1). The first cluster consists of questions DT_2, 4, 6, 8, 11; the second cluster: DT_1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, with weak (< 0.18) correlation between DT_2 and DT_7. With this purely exploratory approach to the results, it can be seen that the COOPERATION factor expands concerning the theoretical assumptions by item No 2, and the factors of SCHOOL SKILLS and sense of COMPETENCE do not form orthogonal correlation patterns.

Reliability, meaning the robustness of the results over time, was tested through the ICC coefficient for repeated measurements in a random effects model (random effects, multiple raters) - it was sufficient and was ICC (2,k) = 0.70.

ValidityThe validity of the factor analysis was based on the value of the KMO index (MSA = 0.81) and the result of the Bartlett sphericity test (chi2(66) = 11.73, p < .001). An exploratory analysis of the results collected during the first wave confirmed the initial observations about the existence of at least two factors - the VSS (Very Simple Structure) index reaches a maximum value (0.61) for the two-factor solution. The lowest value of the BIC and MAP index for the two-factor solution is another confirmation of this result. However, due to the theoretical assumptions accepting the existence of three factors, the exploratory analysis adopted this solution, which explains 37% of the total variance in the results. Factor loadings analysis confirms the existence of a separate factor measuring the level of cooperation and combined factors measuring school skills and sense of competence.

Due to the lack of multivariate normality of the obtained results estimated using the Mardia test (Mskewn. = 2351, p < .001, Mkurt. = 26.8, p < .001), the Satora-Bentler (2010) correction was used in the confirmatory analyses to calculate the indices of fit of the data to the model. Analyses were performed on the results collected during the second wave (T2).

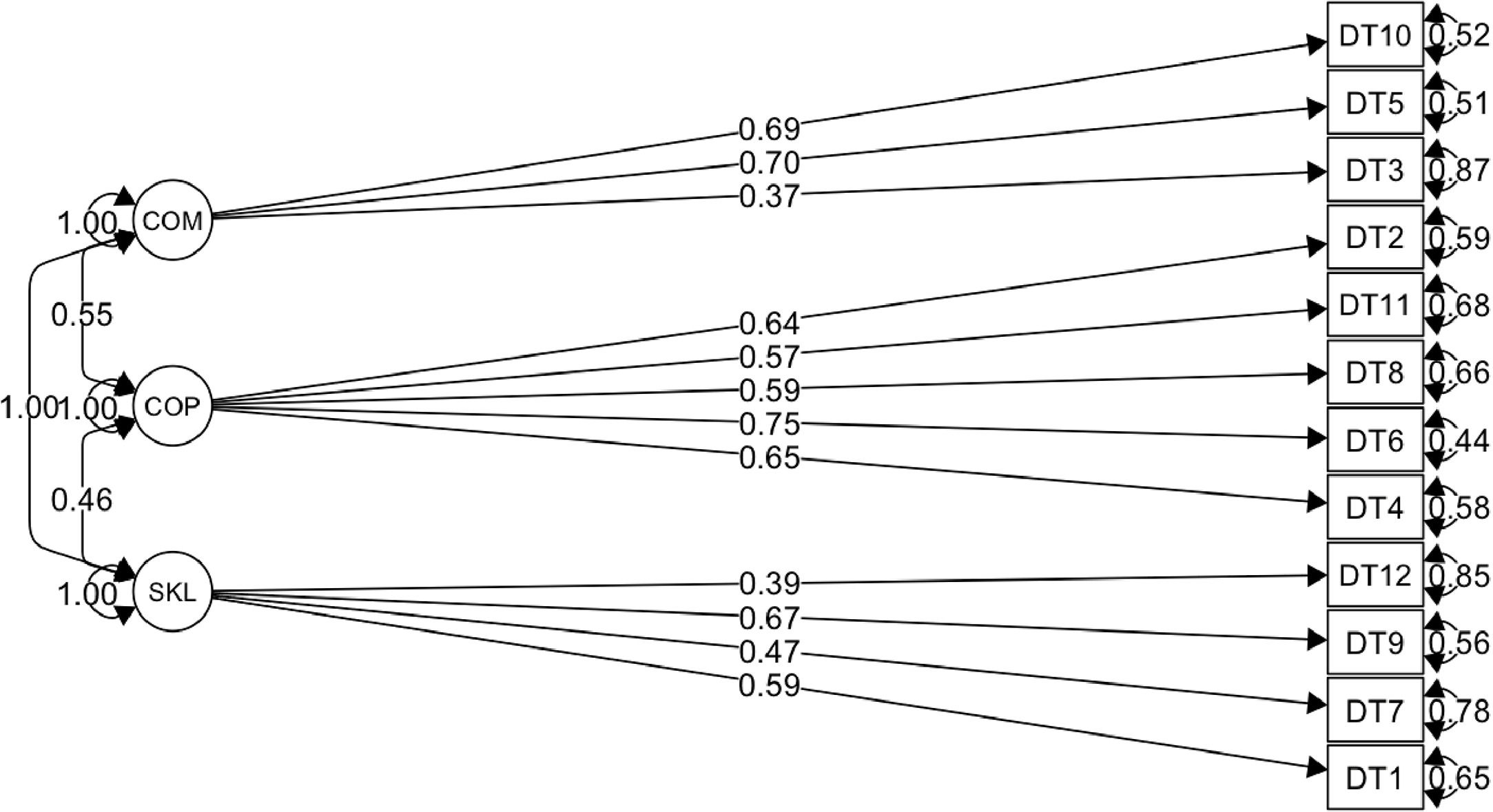

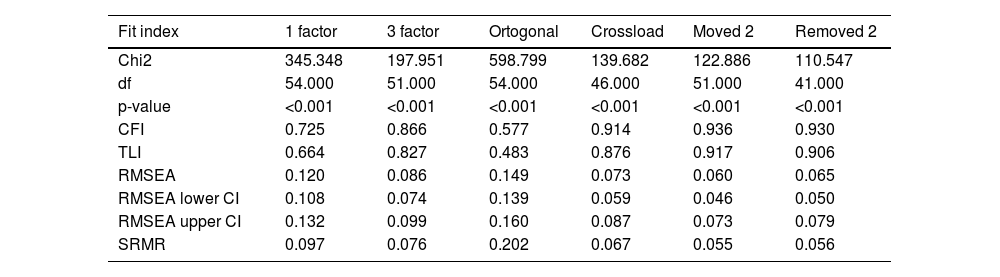

The study of the theoretical structure was based on a confirmatory analysis of several models. A one-factor structure („1 factor”) was used as the base model, followed by a three-factor model („3 factors”) and a three-factor orthogonal model („Orthogonal”), a three-factor model with cross-loading („Crossload”), a model with the DT_2 item moved from the COMPETENCE scale to the COOPERATION scale („Moved 2″) and a three-factor model based on 11 items (without the DT_2 item - „Removed 2″). The first three models are not well enough fitted to the data (CFI < 0.90, RMSEA > 0.08). The last model, consisting of 11 items, appears as the best fit to the data from the second wave (T2). However, it is only marginally better than the model in which problematic item 2 was shifted from the COMPETENCE factor to the COOPERATION factor. For such a model (shown in Fig. 2), the recommended levels for the CFI/TLI fit indices (>0.90) and error rate (RMSEA < 0.08, SRMR < 0.06) were achieved. The fit indices for all analysed models are shown in Table 1.

Models fit comparison.

Note. CFI – comparative fit index, TLI – Tucker–Lewis index, RMSEA – root mean square error of approximation, CI – confidence interval, df – degrees of freedom, SRMR – squared root mean residuals. All indices are after the Satorra–Bentler correction.

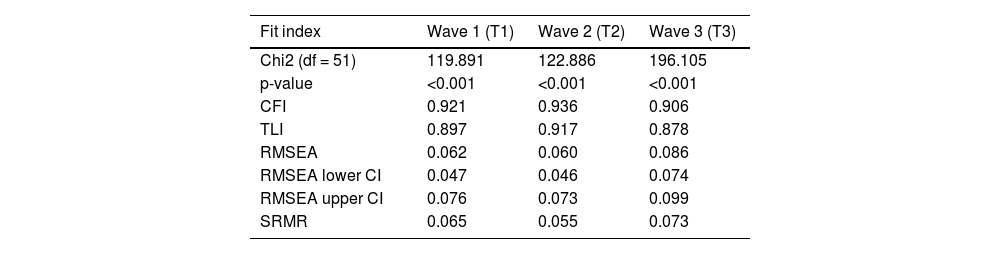

For the accepted model, fit and error indices were calculated for the data collected in the three waves (T1, T2, T3 – see Table 2). The model proved to be a good fit for the data from the first measurement (T1), while for the data from the third measurement (T3), the fit indices are slightly above the required threshold levels. The difference may be due to the different testing situation during T3, as the participating children were completing additional tests related to their educational course at this time. The higher cognitive load may have decreased attention and decreased pupils' concentration when completing the psychological questionnaire.

Model fit indices for three waves of data collections.

Note. For abbreviations, see note in Table 1.

Based on the selected model, composite reliability was estimated, which was CR = 0.867, confirming convergent validity. The AVE values for each scale met the condition of exceeding the maximum shared variance and were respectively: AVESKL = 0.289 > MSV = 0.215, AVECOP = 0.414 > MSV = 0.304, AVECOM = 0.389 > MSV = 0.304.

Associations of QADT scores with satisfaction and depressionSpearman's rho correlation coefficient was used to assess the relationship between developmental task scores, life satisfaction, and depression levels. As a normal distribution did not characterise the results, a bootstrap method with 5000 samples was used to determine 95% confidence intervals around the results.

The results collected at T3 were analysed separately at grades 4, 5 and 6, obtaining a moderate correlation with satisfaction in each case (rho4 = 0.639, 95%CI = [.533, 0.732]; rho5 = .659, 95% CI = [.488,.792]; rho6 = 0.681, 95% CI = [.580, 0.766].)

Similarly, a correlation consistent with the hypothesis was found between the completion of developmental tasks and the level of depression - the relationship was negative and moderate (rho4 = −0.604, 95% CI = [−0.703, −0.490], rho5 = −0.569, 95% CI = [−0.713, −0.389], rho6 = −0.529, 95% CI = [−0.638, −0.409]).

DiscussionAs a result of the analyses, it was possible to establish that the developmental tasks of middle childhood are a multidimensional construct that three factors can describe. These factors are not exhaustive from the point of view of developmental psychology. However, they are sufficient to assess the child's fulfilment of the most important social expectations for adaptation and proper functioning. This result corresponds to the assumptions of Havighurst's (1948/1981) concept of developmental tasks and the research in this area (Havighurst, 1948). The similarity of the results in the first and second measures confirms the factorial stability and reliability of the QADT questionnaire. An additional argument may be that the three-factor structure and the correspondingly high reliability of the scales were maintained despite the differences in age and gender proportions between the first and second groups of subjects.

The confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data of the three-factor model of developmental tasks during middle childhood. However, the questionnaire has limitations regarding the non-orthogonality of the factors of SCHOOLS SKILS and sense of COMPETENCE. Nonetheless, further samples should be included in the study to increase confidence in this regard. The study obtained a relatively high level of internal consistency, indicating the reliability of the scales of the discussed method. The criterion-related validity of the method was also estimated by correlating it with external criteria, such as life satisfaction and the severity of depressive symptoms. According to Havighurst's conceptualisation, the success or failure of a particular stage's developmental tasks affects the completion level of subsequent tasks and the young person's functioning in many areas. As research indicates, areas sensitive to the quality of developmental tasks include life satisfaction (Soares et al., 2019) and levels of psychopathology, including depression (Reed, 1986; Salmela-Aro et al., 2012). The sound theoretical foundation of the construct of developmental tasks in the context of developmental psychopathology confirms the validity of using the QADT tool to assess the level of achievement of developmental tasks during middle childhood. The presented studies resulted in a tool with satisfactory psychometric properties. These findings demonstrate that the QADT scale can be used to evaluate the level of fulfilment of developmental expectations in school-aged children. This allows for the use of this tool in both scientific and applied research in the fields of developmental psychology, developmental psychopathology, and child clinical psychology because the developmental tasks are the same for all children, whether they are struggling with mental health problems or not. Due to the limited number of items, the questionnaire is particularly useful in this age group and in time-consuming studies that use batteries of tests composed of multiple instruments.

When considering the limitations of the present study, it is important to take into account that the validation analyses of the QADT questionnaire were conducted on a sample composed only of children attending urban primary schools. This limits the scope of generalisation of the results, but a universal tool has been created for children from various backgrounds. Further research using the method presented in the article may aim to establish its psychometric properties in other samples. Further investigations of the factor structure of the QADT questionnaire, conducted on larger samples than those collected in this study, are also necessary. This would allow for a re-examination of the factor structure of this tool. Both methods also require further validation studies that verify their validity using approaches and methods other than those employed in this study.

ConclusionsThe growing social expectations towards young people, as well as the increasingly experienced difficulties and psychological suffering they face, pose new challenges for psychologists, educators, and scientists alike. Research conducted in the developmental psychopathology paradigm shows that taking developmental aspects into account in the development of symptoms and mental disorders in children increases the chance of understanding the conditions and course of diverse developmental pathways leading either to mental health or pathology (Cicchetti, 1993; Martinius, 1993; Masten et al., 2006). Success in achieving developmental tasks during middle childhood provides a basis for coping well with the challenges of one of the more difficult periods, adolescence (Hurrelmann & Quenzel, 2018; Kessler et al., 2005; National Research Council & Institute of Medicine, 2000; Pynoos et al., 1999). Therefore, it is important from both scientific and practical perspectives to analyse and disseminate the significance of the achievement of developmental tasks by children in the context of their functioning and adaptation to constantly changing socio-historical conditions (Gregory et al., 2007; Kellam et al., 1998; Masten et al., 2008). Reliable and valid tools for measuring the level of achievement of developmental tasks are essential for this purpose. The presented tool meets the reliable and valid method criteria and can be used in scientific research.

ContributionsG.I. and F.A. conceptualized the research project and developed the methodology, with G.I. also acquiring funding and supervising the planning and execution of the research activities, including external mentorship. F.A. was responsible for data curation, conducting the investigation, and managing project administration, while both G.I. and F.A. provided the necessary resources for the study. K.P. formally analyzed the study data, validated the overall replication and reproducibility of results, and prepared the visualizations. G.I. and K.P. jointly prepared the initial draft of the manuscript, and G.I. and K.P. collaborated on reviewing and editing the final version.