Fungemia due to uncommon fungi and secondary to multiple risk factors has become an emergent health problem, particularly in oncology patients.

AimsThis study shows the following data collected during an 11-year period in a tertiary care oncologic center from patients with fungemia: demographic data, clinical characteristics, and outcome.

MethodsA retrospective study was performed at Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, a 135-bed referral cancer center in Mexico City, from July 2012 to June 2023. All episodes of non-Candida fungemia were included.

ResultsSixteen cases with uncommon fungemia were found in the database, representing 0.3% from all the blood cultures positive during the study period, and 8.5% from all the fungi isolated. The most common pathogens identified in our series were Histoplasma capsulatum, Acremonium spp., Trichosporon asahii, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eight patients had hematologic malignancies, and five had severe neutropenia. In eight cases fungemia was considered catheter-related, in four cases was classified as primary, and in the last four it was diagnosed as disseminated fungal diseases. Mortality at 30 days was 43.8%.

ConclusionsThe improved diagnostic tools have led to a better diagnosis of uncommon fungal infections. More aggressive therapeutic approaches, particularly in patients with malignancies, would increase survival rates in these potentially fatal diseases.

Las fungemias por hongos poco comunes debidas a múltiples factores de riesgo se han convertido en un problema emergente de salud, particularmente en los pacientes oncológicos.

ObjetivosDescribir las características demográficas, clínicas y la evolución de pacientes con fungemia de un centro de referencia oncológica durante un período de 11 años.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo en el Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, un hospital de 135 camas en la Ciudad de México, un estudio retrospectivo que abarcó de julio de 2012 hasta junio de 2023. Todos los episodios de fungemia debidos a hongos que no fueran del género Candida fueron incluidos.

ResultadosSe documentaron 16 casos de fungemia por hongos poco comunes, lo cual representó el 0,3% de todos los hemocultivos positivos durante el período de estudio, y el 8,5% de todos los aislamientos fúngicos. Los patógenos más comunes identificados fueron Histoplasma capsulatum, Acremonium sp., Trichosporon asahii, y Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Ocho pacientes tenían una neoplasia hematológica y cinco presentaban una neutropenia grave. En ocho casos la fungemia estaba relacionada con el uso de catéter, en otros cuatro casos la fungemia fue catalogada como primaria, y en los cuatro últimos se diagnosticó una infección fúngica diseminada. La mortalidad a 30 días fue del 43,8%.

ConclusionesEl avance en los métodos diagnósticos permite una mejor identificación de infecciones fúngicas por hongos poco comunes. Instaurar de forma oportuna tratamientos aantifúngicos más agresivos, particularmente en pacientes oncológicos, permitiría mejorar la supervivencia en infecciones potencialmente graves.

Fungemia due to uncommon fungi has become an emergent health problem among patients with an impaired immunological condition, especially among those receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy in whom there is skin and mucosal barrier disruption.12 Other cellular and humoral immunosuppression conditions, such as HIV infection and being treated with new monoclonal antibodies, have been recognized as risk factors for acquiring severe fungal infections.12 There are other conditions that also contribute to fungi infection, such as central venous catheter use (CVC), broad-spectrum antibiotics, and parenteral nutrition.

The challenges that we have faced in the past when studying uncommon fungi have been the potential risk of misidentification by conventional phenotypic methods, the delay in the species identification of the strains involved, the clinical management of bloodstream infections by strains intrinsically resistant to certain antifungal agents, and the absence of well-established clinical breakpoints for interpreting the susceptibility testing.9

Nowadays, the incorporation of new identification methods, such as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF), has extended the capacity to identify species of yeasts that do not belong to the genus Candida; these species could have been unidentified in the past. The extended use of automated blood culture system has also increased the yield of microorganisms isolated from blood.6

This study aimed to assess clinical and microbiological features in cases of fungemia due to uncommon fungi, and patients’ outcomes at a tertiary care oncologic center during an 11-year -period.

Material and methodsA retrospective study at Instituto Nacional de Cancerología, a 135-bed referral cancer center in Mexico City, was performed from July 2012 to June 2023. All episodes of non-Candida fungemia were included. The cases were found in the computerized microbiological laboratory database, and all the clinical information was obtained from the medical electronic chart.

Fungemia was defined as the isolation of yeasts or molds from blood cultures in the context of febrile patients without the isolation of other microbes. Fungemia was further classified as (i) catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI): according to IDSA, clinical signs of sepsis and positive peripheral blood culture in the absence of an obvious source other than CVC, and time to positivity between CVC culture and peripheral blood culture greater than 2h15; (ii) primary: fungemia with non-organ disease diagnosed in a patient with signs/symptoms of bloodstream infection (BSI)21; (iii) disseminated disease: patients with two or more sites infected by the same pathogen.

Breakthrough fungemia was defined as an infection in a patient receiving systemic antifungal therapy for at least seven consecutive days before the index blood culture; severe neutropenia was defined as an absolute neutrophil count of ≤500cells/mm3.

MethodologyOur institution's care protocol for patients with fever mandates processing two blood culture bottles (one peripheral and one from each CVC lumen) at least, or two peripheral's in patients without a CVC. Blood cultures were performed in BD Bactec™ Plus Aerobic/F and BD Bactec™ Myco/F Lytic culture vials, and incubated at 35±2°C in the BD BACTEC™ blood culture System (Becton Dickinson).

All positive cultures were sub-cultured on 5% sheep blood agar base, MacConkey agar, chocolate agar, and Sabouraud dextrose agar, and incubated at 37°C. Microbial identification was performed from 2013 to 2019 by means of MALDI Biotyper® 1VD ver. 2.2 (Bruker, UK), and from 2019 to 2023 with Vitek®MS PRIME ver. 3.2 (bioMérieux, France). In the case of molds, the macroscopic features in Sabouraud agar, and the microscopic ones in lactophenol cotton blue staining, were wrote down.

The following clinical information was recorded: age, gender, occupation, comorbidities, type of cancer (classified as solid or hematologic malignancy), the status of cancer at that moment (complete or partial remission, recent diagnosis, relapse or progression), treatment with chemotherapy, type of regime received previous to fungemia, HIV status, CD4+ cells count, radiotherapy, hospitalization and antimicrobials in the previous three months. The following data related to the infection were also recorded: fungal genus/species, site of isolation, symptoms, CT thorax scan, and antifungal treatment. The 30-day mortality rate since the first positive blood culture was considered the primary outcome.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis for continuous and categorical variables was performed. Continuous variables were analyzed with the Student-t test or the Mann–Whitney U test for the corresponding parametric or non-parametric variables. The Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using STATA (ver. 14) statistical software. This study was approved by the Institution's Ethics Committee Instituto Nacional de Cancerología (No. 2023/062).

ResultsDuring the study period, 39,309 blood cultures were taken; 5845 were positive (14.9%), and fungal isolation was reported in 195 (3.3%). In sixteen cases patients were diagnosed with uncommon fungemia (0.3% from all the positive, and 8.5% from all the fungi). Nine patients were men (56.3%) with a mean age of 45.7±12 years. Once the condition of malignancy was diagnosed, the median time to the onset of infection was four months (IQR 2, 31 months).

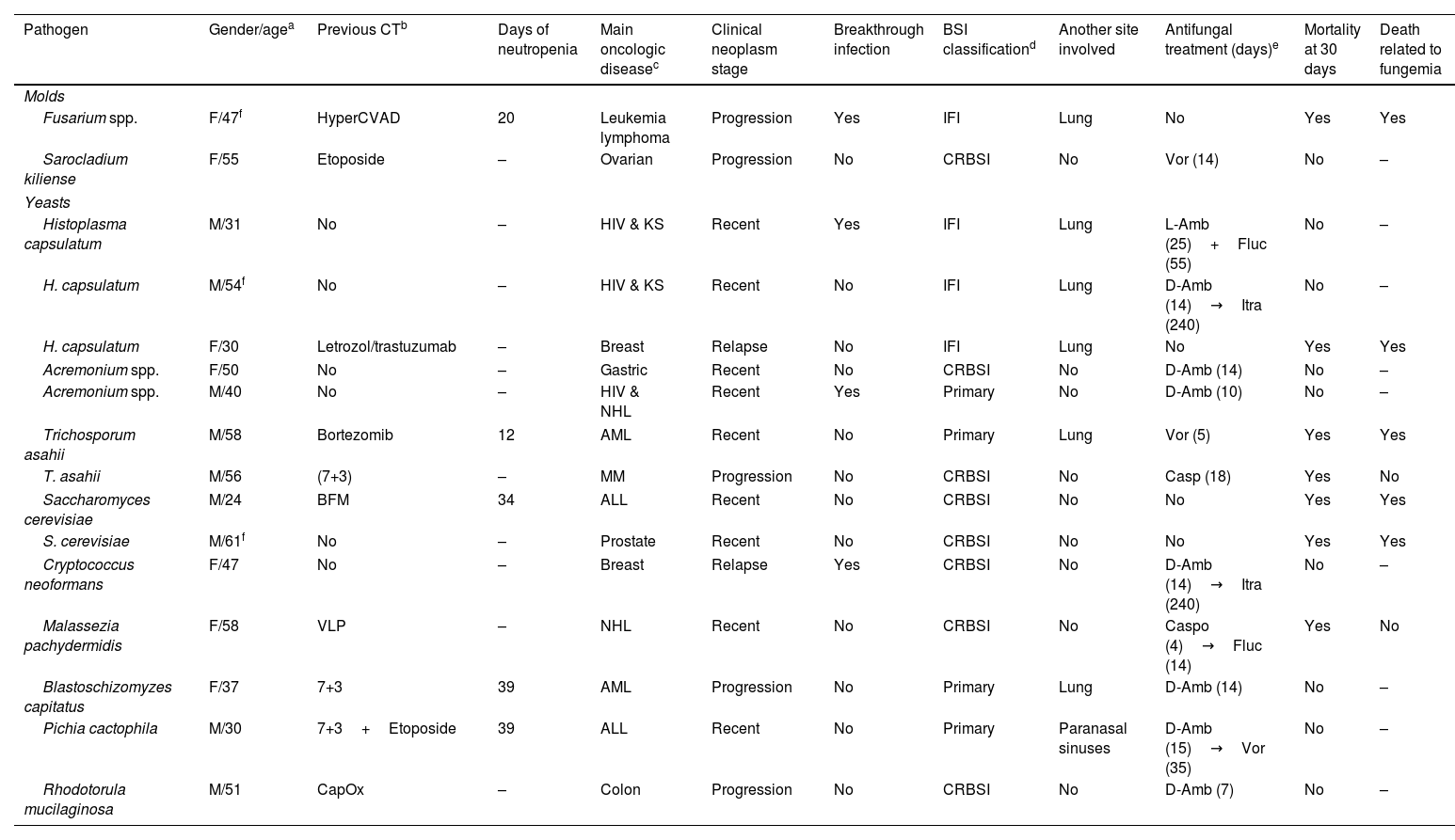

Eight patients (50%) had a hematologic malignancy; five were on their first-line therapy, and three had non-respondent progressive disease. Seven patients had received chemotherapy the previous month; for five of them the regimen was classified as highly myelosuppressive. Five patients had severe neutropenia, with a median of 34 days (IQR 20, 30 days). The length of hospitalization was 30 days (IQR 18, 43 days). None of the patients had received a hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT). The most common pathogens isolated were Histoplasma capsulatum, Acremonium spp., Trichosporon asahii, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Data are shown in Table 1.

Fungi isolated and main characteristics related to fungemia.

| Pathogen | Gender/agea | Previous CTb | Days of neutropenia | Main oncologic diseasec | Clinical neoplasm stage | Breakthrough infection | BSI classificationd | Another site involved | Antifungal treatment (days)e | Mortality at 30 days | Death related to fungemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molds | |||||||||||

| Fusarium spp. | F/47f | HyperCVAD | 20 | Leukemia lymphoma | Progression | Yes | IFI | Lung | No | Yes | Yes |

| Sarocladium kiliense | F/55 | Etoposide | – | Ovarian | Progression | No | CRBSI | No | Vor (14) | No | – |

| Yeasts | |||||||||||

| Histoplasma capsulatum | M/31 | No | – | HIV & KS | Recent | Yes | IFI | Lung | L-Amb (25)+Fluc (55) | No | – |

| H. capsulatum | M/54f | No | – | HIV & KS | Recent | No | IFI | Lung | D-Amb (14)→Itra (240) | No | – |

| H. capsulatum | F/30 | Letrozol/trastuzumab | – | Breast | Relapse | No | IFI | Lung | No | Yes | Yes |

| Acremonium spp. | F/50 | No | – | Gastric | Recent | No | CRBSI | No | D-Amb (14) | No | – |

| Acremonium spp. | M/40 | No | – | HIV & NHL | Recent | Yes | Primary | No | D-Amb (10) | No | – |

| Trichosporum asahii | M/58 | Bortezomib | 12 | AML | Recent | No | Primary | Lung | Vor (5) | Yes | Yes |

| T. asahii | M/56 | (7+3) | – | MM | Progression | No | CRBSI | No | Casp (18) | Yes | No |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | M/24 | BFM | 34 | ALL | Recent | No | CRBSI | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| S. cerevisiae | M/61f | No | – | Prostate | Recent | No | CRBSI | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | F/47 | No | – | Breast | Relapse | Yes | CRBSI | No | D-Amb (14)→Itra (240) | No | – |

| Malassezia pachydermidis | F/58 | VLP | – | NHL | Recent | No | CRBSI | No | Caspo (4)→Fluc (14) | Yes | No |

| Blastoschizomyzes capitatus | F/37 | 7+3 | 39 | AML | Progression | No | Primary | Lung | D-Amb (14) | No | – |

| Pichia cactophila | M/30 | 7+3+Etoposide | 39 | ALL | Recent | No | Primary | Paranasal sinuses | D-Amb (15)→Vor (35) | No | – |

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | M/51 | CapOx | – | Colon | Progression | No | CRBSI | No | D-Amb (7) | No | – |

CT: chemotherapy; HyperCVAD: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; 7+3: cytarabine, daunorubicin; BFM: daunorubicine, vincristine, l-asparaginase, prednisolone, methotrexate; VLP: vincristine, l-asparaginase, prednisone; CapOx: capecitabine, oxaliplatin.

KS: Kaposi sarcoma; NHL: non-Hodgkin lymphoma; AML: acute myeloblastic leukemia; MM: multiple myeloma; ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

There were three patients with HIV, two with disseminated Kaposi sarcoma, and one with non-Hodgkin lymphoma; the CD4+ lymphocyte count was 110, 35, and 279cells/mm3, respectively.

Excluding the two patients with only Kaposi sarcoma, there were six patients with solid tumors: two with recent cancer diagnosis (one with gastric cancer receiving total parenteral nutrition), two with cancer relapse, and two with progressive cancer. Three patients (37.5%) had received chemotherapy during the previous month; none had severe neutropenia. The median length of hospitalization was 19 days (IQR 13, 28 days). Other data are shown in Table 1.

Four patients of the total cohort had received previous antifungal prophylaxis, and their fungal infection was considered breakthrough fungemia.

The clinical classification of the fungemia was as follows: eight patients had CRBSI, four had primary BSI, and four had disseminated fungal disease. In six CRBSI episodes, the CVC was removed; in the other two, fungemia was documented postmortem.

The most common symptoms were fever in 15 patients (93.8%) and dyspnea in 5 (31.3%). Two patients (12.5%) had neurologic deterioration, but no central nervous system fungemia involvement was registered. In 10 patients a CT thorax scan was performed, showing abnormalities in six of them.

Twelve patients received antifungal treatment; in the other four, the diagnosis was postmortem. The median time of antifungal treatment was 16 days (IQR 9, 53 days). The antifungal therapy included amphotericin B deoxycholate in seven patients, voriconazole in three, fluconazole in three, caspofungin in two, itraconazole in one, and liposomal amphotericin (L-Amb) in one. One patient received a combination therapy with L-Amb and fluconazole, and four patients received two different non-overlapping antifungal treatments.

At 30 days, seven patients (43.8%) have died, including the four patients who did not receive any treatment. Two additional patients died within the 90-day follow-up (56.3%).

DiscussionWe identified 16 episodes of uncommon fungemia during eleven years in an oncological center, 0.3% of all positive blood cultures during the study period. A retrospective study in a 1000-bed tertiary care center in Israel reported 13 fungemia episodes during 15 years.11 A multicentric Italian study (33 centers during a 6-year surveillance), which included only patients with hematological malignancies, described 24 non-Candida-yeast-fungemia episodes, and 17 mold-fungemia cases, with 46% and 70% mortatility reported, respectively.5 Another multicentric Colombian study, in patients with hematological malignancies, described two mold fungemias and 19 non-Candida-yeast fungemias during a 7-year period.24

The most common pathogens identified in our series were H. capsulatum, Acremonium spp., T. asahii, and S. cerevisiae. The last three fungi had been reported previously as the more common non-Candida fungi isolated in blood in a study at the MD Anderson Cancer Center that included 94 blood cultures from 41 patients in 12 years.3 Identification of yeasts using MALDI-TOF, a high reliability method, has proven to be very useful, as it is rapid, effective, less expensive once you count with the equipment, enables the identification of more clinically significant yeasts, as well as the differentiation of closely related species, and allows starting a specific treatment in the short term.10

The yeasts identified in this series are common saprophytic fungi, ubiquitous in the environment. They are not frequently involved in human infections and, when they do, it is usually in immunocompromised hosts. Patients with hematological malignancies and HSCT are in high risk of suffering invasive fungal infections (IFI).11 In this case series, half of the patients had hematological malignancies; in five, the fungemia episodes were in patients with severe neutropenia. None of the patients had received HSCT.

Six patients had solid tumors, and none of them had neutropenia during the fungemia. Only one patient was receiving total parenteral nutrition.

Only two molds were isolated: one Fusarium and one Sarocladium kiliense. Fusarium causes invasive infections in patients with uncontrolled hematologic malignancies or in those who receive HSCT. Patients usually have severe neutropenia, and the fungus can be isolated from blood cultures in one-third of the patients. Skin involvement is the first clue in most cases of disseminated fusariosis, often occurring early in the disease. Multiple erythematous macular painful lesions are reported in 70% of the cases. Mortality at 12 weeks has been estimated in 95%.2 There is a female patient in our series that suffered from progressive leukemia/lymphoma and severe neutropenia for 20 days. She had received antifungal prophylaxis with fluconazole for ten days, two days before diagnosing Fusarium fungemia; first signs and symptoms were a disseminated dermatosis and fever and, only one day after, the patient developed severe sepsis and died. The Fusarium species was not identified since MALDI-TOF identification percentage was low (Fusarium solani 50% and Fusarium oxysporum 50%).

The other mold isolated, S. kiliense (previously known as Acremonium kiliense), is a saprophyte fungus associated with invasive procedures. The infection is characterized by mild clinical manifestations and it is not associated with mortality. In a Chilean multicenter outbreak in 2013, S. kiliense was isolated from a parenteral drug.17 The patient in our series had been diagnosed with progressive ovarian cancer and had a long-term CVC. After the manipulation of the catheter in another hospital, the patient began to experience fever and chills. Blood cultures were performed, recovering S. kiliense. The catheter was removed and the patient received voriconazole for 14 days, with resolution of the infectious process.

The dimorphic fungus H. capsulatum was the most isolated. It causes infection in patients with advanced HIV/AIDS, but it is also linked to other immune-suppressive conditions.1 In this case series two patients were HIV+, and their CD4+ count was less than 100cells/mL; the third patient had breast cancer with severe neutropenia. The three patients had disseminated invasive fungal disease with lung involvement (one patient died).

Acremonium spp. is a filamentous, cosmopolitan fungus, frequently isolated from plant debris and soil that has emerged as an important cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised patients.20 Two patients suffered a fungemia due to this fungus, one hematological patient with severe neutropenia that developed a primary fungemia, and the other (with gastric cancer and receiving total parenteral nutrition) with CRBSI. Both patients survived. We had previously reported the cases of two patients with CRBSI by Acremonium, both with total parenteral nutrition, who survived.4 The species of Acremonium are morphologically very similar to each other and can only be distinguished through subtle differences, at best. Hence, the identification of any species based exclusively on morphological features is difficult.18

Trichosporon species have been described as the second most common cause of fungemia in patients with hematological malignancies, with increasing cases in recent years.7 It exhibits an intrinsic resistance to echinocandins and a poor susceptibility to polyenes.7 Voriconazole is the drug of choice, associated with better outcomes.13 Fungemia by Trichosporon has been associated with a high mortality rate (51.5%), being of 30.3% in those cases caused by T. asahii.13 In our series we had two cases of T. asahii infection, one primary fungemia due to severe neutropenia in a patient with acute leukemia (who died on the third day), and a CRBSI in a non-neutropenic patient with multiple myeloma (who died after eight days).

Two patients had CRBSI due to S. cerevisiae, one with acute leukemia and the other with prostate cancer. Both patients died. This yeast is a ubiquitous ascomycetous fungus that is part of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and vaginal microbiota. Portals of entry include the translocation of ingested microorganisms from the enteral or oral mucosa, and contamination of CVC insertion sites.16

Cryptococcus neoformans was isolated in a non-neutropenic patient with breast cancer with CRBSI. Most cases of cryptococcemia described in non-HIV patients are secondary to non-C. neoformans species, such as Cryptococcus laurentii or Cryptococcus gattii.

Malassezia genus comprises 18 lipid-dependent species that may inhabit the skin and mucosa of humans and animals, being Malassezia pachydermatis the only species able to grow in Sabouraud agar, so it is easier to identify.19 They may cause dermatitis and bloodstream infections in neonates and immunocompromised hosts, especially those receiving parenteral nutrition. It can also form biofilms; infections linked to CVCs are the ones reported in this study. Even though the catheter was removed early, the patient in our series died.

Blastoschizomyces capitatus is a rare yeast that produces severe systemic infection in hemato-oncologic patients. The mortality rate reported at 30 days is 60%, with a better survival when the CVC is removed promptly.14 Resistance to amphotericin B and fluconazole has been involved in breakthrough infections.14 Our patient had acute leukemia, severe neutropenia, and fungemia with lung involvement, but survived.

Yeasts belonging to Pichia genus are scarcely found in human samples. In a study performed in Chinese hospitals, Pichia was the most common non-Candida yeast isolated, along with Rhodotorula, Saccharomyces, and Cryptococcus spp.8 The species documented in this series, Pichia cactophila, has been mainly found in some cactus species. The case in our series was a primary fatal fungemia in a patient with acute leukemia.

Rhodotorula species are commensal yeasts that have emerged as a cause of life-threatening fungemia in severely immunocompromised patients.22 In a report that included 128 cases, the most common risk factor was the use of CVC. Rhodotorula mucilaginosa is the most common species (74%), and the reported mortality is 12.6%.23 These yeasts are resistant to fluconazole, posaconazole, voriconazole, and echinocandins; amphotericin B is the proper antifungal treatment. In our series, R. mucilaginosa was isolated from a patient with CRBSI. The CVC was removed, the patient received seven days of amphotericin B and survived.

ConclusionThe growing number of severely immunosuppressed patients, the increasing awareness of physicians and microbiologists, and the improved diagnostic tools have led to a better diagnosis of uncommon fungal infections. The correct identification of the fungus involved is mandatory for an appropriate management, as some of the fungi can show intrinsic resistance to some antifungal agents. More aggressive therapeutic approaches at the beginning, particularly in patients with malignancies, will help to reduce the mortality rates associated with these potentially fatal diseases.

FundingThis study did not receive any funding.

Authors’ contributionsRMFD: Investigation

PV: Review and editing

CVA: Investigation

PCJ: Conceptualization, writing, and editing

Competing interestsThe authors declare they do not have competing interests.

We thank all the staff of the Laboratory of Microbiology.