An outbreak of S.Typhimurium occurred in several towns and cities in the province of Castellon (Spain) between 23 February and 27 May 2011. On April 5, the microbiology laboratory of a hospital in Castellon alerted the health authorities to the increase in S.Typhimurium isolated in fecal culture of children with gastroenteritis. The serotype and phage-type of 83 positive cases of S.Typhimurium isolated in these period included 49 monophasic/biphasic S.Typhimurium phage type 138, phage type 193, S.Derby, and 34 other S.Typhimurium phage-types. The median of age of patients was 4 years with a range of 0.6–80 years, and the 18% of patients were hospitalised. Two incident matched case–control studies were carried out; the first with S.Typhimurium phage type 138, 193, and S.Derby cases and the second with the other cases. The two studies found that the consumption of brand X dried pork sausage, purchased in a supermarket chain A, was associated with the disease (matched Odds Ratio [mOR]=13.74 95% Confidence Interval [CI] 4.84–39.06 and mOR=8.20 95% CI 2.32–28.89), respectively). S.Typhimurium phage type 193 and S.Derby were isolated in the food taken from the household of two patients and from the supermarket chain's A central warehouse. The pulsed-field gel electrophoresis study confirmed the similarity of the strains from the patients and the food. On May 25 2011, a national food alert led to the withdrawal of the food from the chain A and the outbreak ended.

Entre el 23 de febrero y el 27 de mayo del 2011, un brote de Salmonella Typhimurium ocurrió en varios pueblos y ciudades en la provincia de Castellón (España). El día 5 de abril del 2011 el laboratorio de Microbiología de un hospital de Castellón alertó a las autoridades sanitarias del incremento de aislamientos de S.Typhimurium en coprocultivos de niños con gastroenteritis. El serotipo y fagotipo de 83 casos positivos a S.Typhimurium aislados en este periodo incluyó 49 casos con monofásica/bifásica S.Typhimurium fagotipo 138, fagotipo 193, y Salmonella Derby y otros 34 casos con distintos S.Typhimurium fagotipos. La mediana de los pacientes era de 4 años, con un rango de 0,6 a 80años. Dos incidentes casos-control apareados fueron llevados a cabo, el primero con los casos S.Typhimurium fagotipos 138,193 y S.Derby, y el segundo con los demás casos. Los 2 estudios encontraron que el consumo de la marca X de longaniza seca de cerdo comprada en una cadena de supermercados A estaba asociado con la enfermedad (odds ratio apareada [ORa]=13,74; intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 4,84-39,06, y ORa=8,20; IC95%: 2,32-28,89, respectivamente). S.Typhimurium fagotipo 193 y S.Derby fueron aislados en dicho alimento recogido en la casa de 2 pacientes y en el almacén central de la cadena A de supermercados. La electroforesis en gel de campo pulsado confirmó la similitud de las cepas de los pacientes y del alimento. El día de 25 de mayo de 2011 una alerta alimentaria nacional obligó a la retirada del alimento de la cadena A y el brote terminó.

In Spain during August 1997, a monophasic S.Typhimurium (4,5,12:i:-) was isolated from human and food samples with affecting of 14 of the 17 Spanish Autonomous Communities. All positive food isolates corresponded to pork and pork products and it was indicated that this strain “has emerged and spread to human in Spain, probably with contaminated pork as the source”.1,2 From 1998 to 2000 in New York, a monophasic variant 4,5,12:i:- caused a food poisoning outbreak.3 In the Europe Union an increase of this monophasic variant of serovar Typhimurium has been observed over the last ten years, and the likely reservoir of infection, as in the Spanish case, is pigs.4,5

On April 5 2011, the Microbiology Laboratory of the General Hospital in Castellón (Spain) alerted the Epidemiology Division of the Public Health Center to a major increase of positive fecal culture S.Typhimurium in children with gastrointestinal symptoms. In this context, the aim of this study was to identify the cause of the infection and to take measures in order to control and prevention further spread of the disease.

MethodsThe outbreak occurred during the local holydays, from March 26 to April 3 2011, in the city of Castellon, the capital of the province of Castellon with 170,000 inhabitants. A descriptive epidemiologic study was begun to considering the case definition and characteristics of patients: clinical symptoms, evolution and time and place of each case and potential risk factors of salmonellosis. All S.Typhimurium positive cases from the General Hospital of Castellon were investigated. Two incident matching case–control studies were then begun when the descriptive study generated a hypothesis relating to the sources of infection and before the serotyping and phage typing of the S.Typhimuriun were carried out. When the serotyping and phage typing were performed, positive cases of S.Typhimurium from the Microbiology Laboratory of the Hospital La Plana in Vila-real, a city of 50,000 inhabitants situated 6km from Castellon, were included in the study. Once these results had been obtained, two matched case–control studies were performed.

In the first incident matched case–control study, the definition of case was a patient during the period February to May 2011 with positive monophasic/biphasic S.Typhimurium phage type 138, S.Typhimurium phage type 193 or S.Derby isolated from fecal urine or blood cultures. In the second incident matched case–control study, the definition of case was a patient during the period February to May 2011 with positive S. Typhimurium phage type 104b, 21, U311, U302, 195, and un-typable phage types isolated from fecal cultures.

The matched case–control studies (1 case:2 controls), were matched by age (less than 1 year) and gender, and each control was chosen at random from the list of patients of the pediatrician or general practitioner who attended the case. Before contact was made with controls, their pediatrician or general practitioners were consulted and verbal consent was obtained. Verbal consent to participate was also obtained from the controls or their parents. An ad hoc questionnaire was used to obtain information on demographic characteristics and potential risk factors; the same questionnaire was used for cases and controls. Information on food exposure was obtained from questions about the consumption of the presumed source foods and other risk factors in a period of up to 15 days before the start of symptoms in the cases; for controls, enrolment was considered equivalent to the day symptoms started in the cases. If the control had suffered gastroenteritis in the 15 days before the interview, he or she was excluded. Information about cases was obtained through face to face or telephone interviews by the epidemiology division staff. Telephone interviews were used with the controls, and if contact had not been established after five telephone calls, another control was randomly chosen from the list.

Microbiological study- -

Isolation of S.Typhimurium and Salmonella spp from human clinical specimens was performed by the Microbiology Laboratories at the Hospital General of Castellon and Hospital La Plana of Vila-real.

- -

Isolations of S.Typhimurium and Salmonella spp from food samples were carried out by the Microbiology Laboratory at the Public Health Center and the Microbiology Laboratory at the Valencia Public Health Center.

- -

Serotyping and phage-typing of Salmonella strains from human and food samples. Salmonella isolates were serotyped at the Spanish National Reference Laboratory Majadahonda (Madrid) for Salmonella by the slide agglutination method using commercial antisera (Bio-Rad; Statents Serum Institut; Izasa).

- -

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Salmonella isolates were characterized by PFGE using XbaI enzyme (Fermentas Life Sciences) for total DNA digestion, following the PulseNet-Europe protocol (http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/protocols.htm) at the National Reference Laboratory.

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Crude and adjusted matched odds ratio (mOR) were estimated as measures of associations between the disease and risk factors with 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated by conditional logistic regression following the matched case–control study using the Stata® 9.0 program.6 Epi Info® version 67 was used to calculate the dose-response test and attributable risk fraction.

To estimate the sample size for the matched case–control studies, it was considered that 25% of the controls were exposed the source of infection. A sample size of 38 cases and 75 controls (1 case: 2 controls) was then required in order to detect an OR of 4.0 with a power of 90% and alpha error of 5%.8

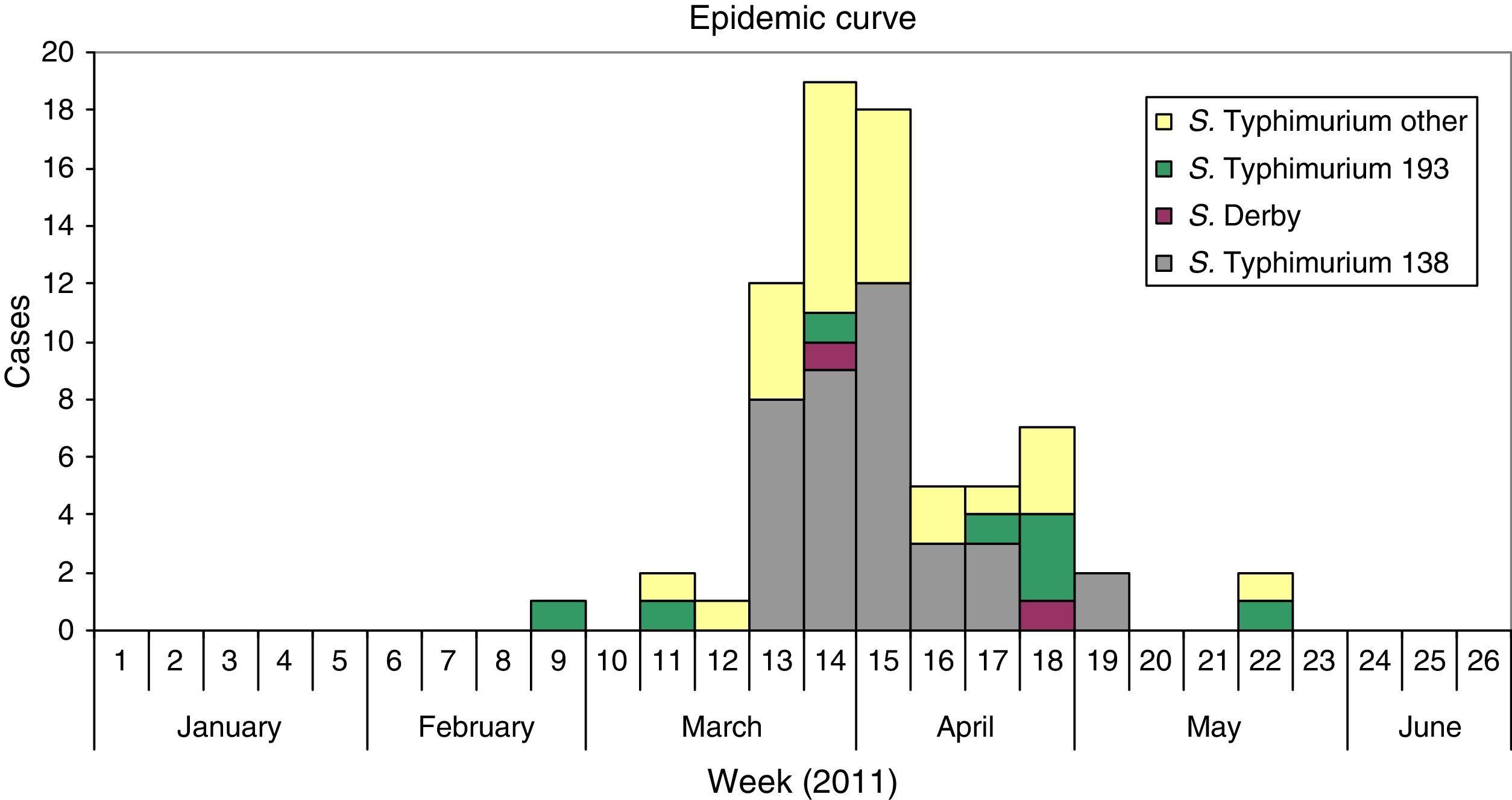

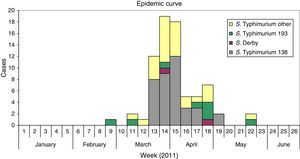

ResultsDescriptive epidemiologyThe outbreak started on February 23 and finished on May 27 2011, with a high incidence of cases between March 21 and April 10, weeks 13 and 15, during the local holydays in Castellon. Fig. 1 shows the epidemic curve suggesting a continuing common source of infection. The cases were located in several towns and cities of the in the province of Castellon, including Castellon, Benicassim, and Vila-real.

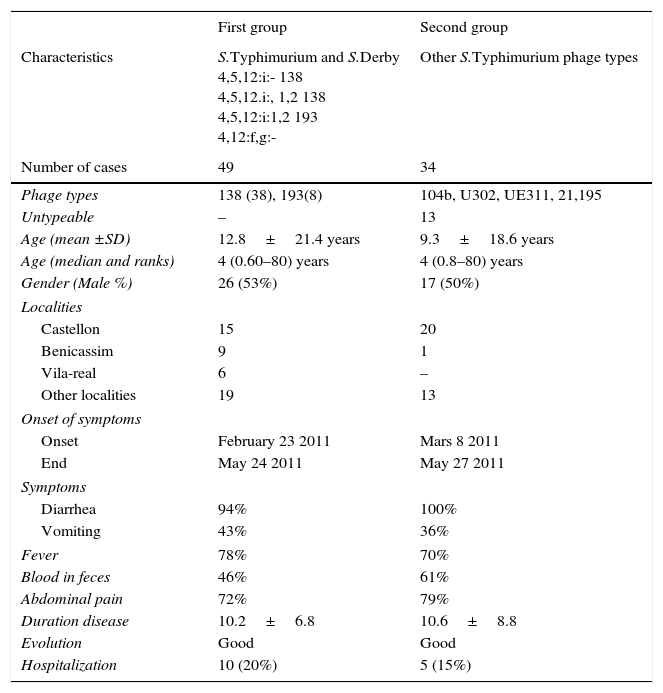

From 85 positive cases of S.Typhimurium isolated in the period February to May 2011, 83 cases could be studied (97.6%), and two groups of patients were considered. The first group included 49 patients with monophasic S.Typhimurium phage type 138, S.Typhimurium phage type 193, and S.Derby. The second group include 34 patients positive to S.Typhimurium including phage types104b, 21, U302, and untypable. Table 1 presents the characteristic of the patients of the two groups, monophasic S.Typhimurium phage type 138 S.Typhimurium phage type 193 and S.Derby and the other group of monophasic/biphasic S.Typhimurium phage types. The first and the second groups had a median of age of 4 years, ranking from 0.6 to 0.8 years to 80 years; the percentages of male were 53% and 50%, respectively.

Characteristics of two group of patients of gastroenteritis following the isolation of different phage types S.Typhimurium and S.Derby.

| First group | Second group | |

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | S.Typhimurium and S.Derby 4,5,12:i:- 138 4,5,12.i:, 1,2 138 4,5,12:i:1,2 193 4,12:f,g:- | Other S.Typhimurium phage types |

| Number of cases | 49 | 34 |

| Phage types | 138 (38), 193(8) | 104b, U302, UE311, 21,195 |

| Untypeable | – | 13 |

| Age (mean ±SD) | 12.8±21.4 years | 9.3±18.6 years |

| Age (median and ranks) | 4 (0.60–80) years | 4 (0.8–80) years |

| Gender (Male %) | 26 (53%) | 17 (50%) |

| Localities | ||

| Castellon | 15 | 20 |

| Benicassim | 9 | 1 |

| Vila-real | 6 | – |

| Other localities | 19 | 13 |

| Onset of symptoms | ||

| Onset | February 23 2011 | Mars 8 2011 |

| End | May 24 2011 | May 27 2011 |

| Symptoms | ||

| Diarrhea | 94% | 100% |

| Vomiting | 43% | 36% |

| Fever | 78% | 70% |

| Blood in feces | 46% | 61% |

| Abdominal pain | 72% | 79% |

| Duration disease | 10.2±6.8 | 10.6±8.8 |

| Evolution | Good | Good |

| Hospitalization | 10 (20%) | 5 (15%) |

The patients of the two groups presented a similar symptoms (Table 1), including diarrhea (94% versus 100%), vomiting (43% versus 36%), fever (78% versus 70%), blood in feces (46% versus 61%), abdominal pain (72% versus 79%). The duration of the disease was similar, 10 days with a good evolution of all cases. The hospitalization rate was higher in the first group, 20% versus 15%.

The hypotheses to tested in the cases–control studies was that the source of the outbreak was a food contaminated with S.Typhimurium, brand X dried pork sausage or “longaniza de Pascua” in Spanish, considering the following factors: the epidemic curve, the lack of relationship among cases, the high percentage of 26 first patients who had consumed this food purchased in an major supermarket chain A, the food is ready to eat and is consumed raw, children usually like this food, the food is typical in the Autonomous Community of Valencia and it consumed during the Easter period. In addition, there were no patients with origin from the Maghreb (the Islamic religion prohibits the consumption of pork), and pigs are considered to be an animal reservoir of monophasic S.Thyphimurium.4

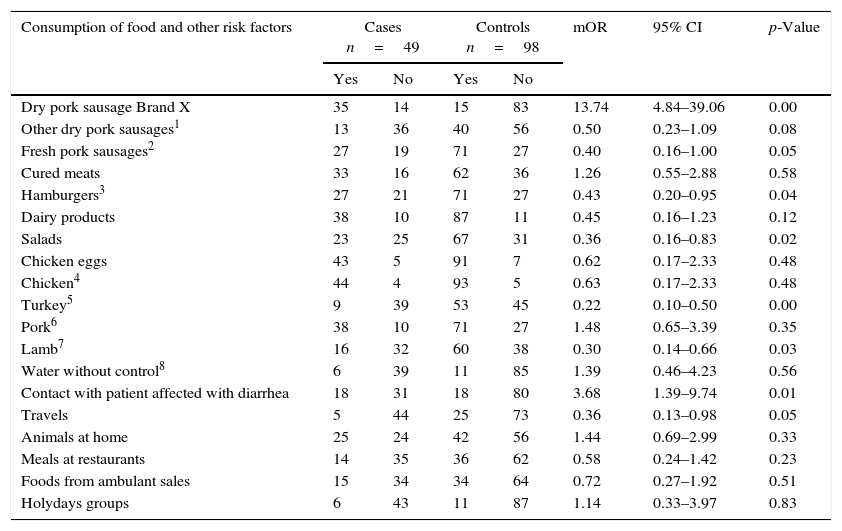

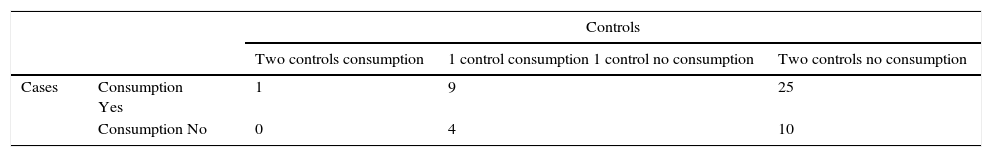

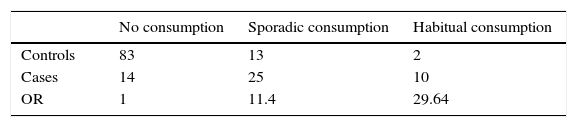

Matched case–control studiesThe first matched case–control study found two positive associations between S.Typhimurium and S.Derby gastroenteritis and the consumption of brand X dried pork sausage purchased in supermarket chain A (mOR=13.74 95% CI 4.84–39.06), and the contact with diarrhea patients (mOR=3.68 95% CI 1.39–9.74) in the conditional logistic regression analysis (Table 2). After the multivariate analysis only the consumption of the food was associated with the gastroenteritis (adjusted mOR=12.55 95% CI 4.33–36.36). The distribution of matched cases and controls relating to the consumption of brand X dried pork is shown in Table 3. The attributable fraction of the risk was 93% (95% CI 84.2–97.1%). A dose–response relationship between the quantity of this food consumed and the risk of the disease was significant p<0.001 (Table 4).

First incident matched case–control study. Cases are patients positive to S.Typhimurium phage type 138 or S.Typhimurium phage type 193, or S.Derby.

| Consumption of food and other risk factors | Cases n=49 | Controls n=98 | mOR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Dry pork sausage Brand X | 35 | 14 | 15 | 83 | 13.74 | 4.84–39.06 | 0.00 |

| Other dry pork sausages1 | 13 | 36 | 40 | 56 | 0.50 | 0.23–1.09 | 0.08 |

| Fresh pork sausages2 | 27 | 19 | 71 | 27 | 0.40 | 0.16–1.00 | 0.05 |

| Cured meats | 33 | 16 | 62 | 36 | 1.26 | 0.55–2.88 | 0.58 |

| Hamburgers3 | 27 | 21 | 71 | 27 | 0.43 | 0.20–0.95 | 0.04 |

| Dairy products | 38 | 10 | 87 | 11 | 0.45 | 0.16–1.23 | 0.12 |

| Salads | 23 | 25 | 67 | 31 | 0.36 | 0.16–0.83 | 0.02 |

| Chicken eggs | 43 | 5 | 91 | 7 | 0.62 | 0.17–2.33 | 0.48 |

| Chicken4 | 44 | 4 | 93 | 5 | 0.63 | 0.17–2.33 | 0.48 |

| Turkey5 | 9 | 39 | 53 | 45 | 0.22 | 0.10–0.50 | 0.00 |

| Pork6 | 38 | 10 | 71 | 27 | 1.48 | 0.65–3.39 | 0.35 |

| Lamb7 | 16 | 32 | 60 | 38 | 0.30 | 0.14–0.66 | 0.03 |

| Water without control8 | 6 | 39 | 11 | 85 | 1.39 | 0.46–4.23 | 0.56 |

| Contact with patient affected with diarrhea | 18 | 31 | 18 | 80 | 3.68 | 1.39–9.74 | 0.01 |

| Travels | 5 | 44 | 25 | 73 | 0.36 | 0.13–0.98 | 0.05 |

| Animals at home | 25 | 24 | 42 | 56 | 1.44 | 0.69–2.99 | 0.33 |

| Meals at restaurants | 14 | 35 | 36 | 62 | 0.58 | 0.24–1.42 | 0.23 |

| Foods from ambulant sales | 15 | 34 | 34 | 64 | 0.72 | 0.27–1.92 | 0.51 |

| Holydays groups | 6 | 43 | 11 | 87 | 1.14 | 0.33–3.97 | 0.83 |

mOR, matched odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Some items 1–8 without completed information among cases and control.

Distribution of matched case–control study. First incident matched case–control study. Consumption of dry pork sausage brand X.

| Controls | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two controls consumption | 1 control consumption 1 control no consumption | Two controls no consumption | ||

| Cases | Consumption Yes | 1 | 9 | 25 |

| Consumption No | 0 | 4 | 10 | |

Matched Odds ratio by conditional logistic regression=13.74 (95% CI 4.84–39.06)

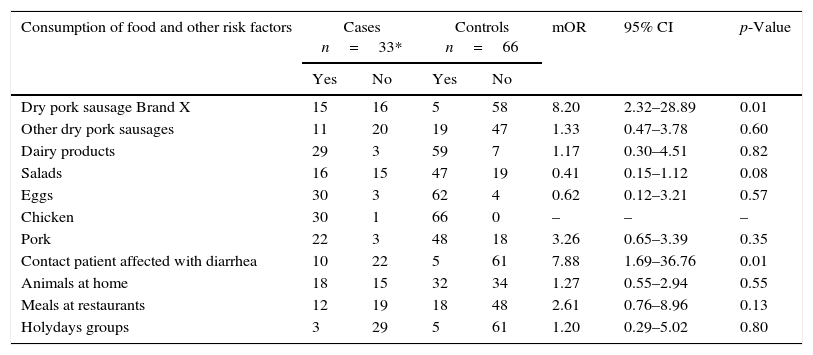

In the second matched case–control study with the positive cases were of other S.Typhimurium phage types (Table 5), the gastroenteritis was associated with the same food consumption and contact with diarrhea patients (mOR=8.20 95% CI 2.32–28.89) and (mOR=7.88 95% CI 1.69–36.76). In the multivariate analysis, the two factors maintained the association.

Second incident matched case–control study. Cases are patients positive to other S.Typhimurium phage types.

| Consumption of food and other risk factors | Cases n=33* | Controls n=66 | mOR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Dry pork sausage Brand X | 15 | 16 | 5 | 58 | 8.20 | 2.32–28.89 | 0.01 |

| Other dry pork sausages | 11 | 20 | 19 | 47 | 1.33 | 0.47–3.78 | 0.60 |

| Dairy products | 29 | 3 | 59 | 7 | 1.17 | 0.30–4.51 | 0.82 |

| Salads | 16 | 15 | 47 | 19 | 0.41 | 0.15–1.12 | 0.08 |

| Eggs | 30 | 3 | 62 | 4 | 0.62 | 0.12–3.21 | 0.57 |

| Chicken | 30 | 1 | 66 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Pork | 22 | 3 | 48 | 18 | 3.26 | 0.65–3.39 | 0.35 |

| Contact patient affected with diarrhea | 10 | 22 | 5 | 61 | 7.88 | 1.69–36.76 | 0.01 |

| Animals at home | 18 | 15 | 32 | 34 | 1.27 | 0.55–2.94 | 0.55 |

| Meals at restaurants | 12 | 19 | 18 | 48 | 2.61 | 0.76–8.96 | 0.13 |

| Holydays groups | 3 | 29 | 5 | 61 | 1.20 | 0.29–5.02 | 0.80 |

mOR, matched odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. *A case without food questionnaire. Some items without completed information among cases and control.

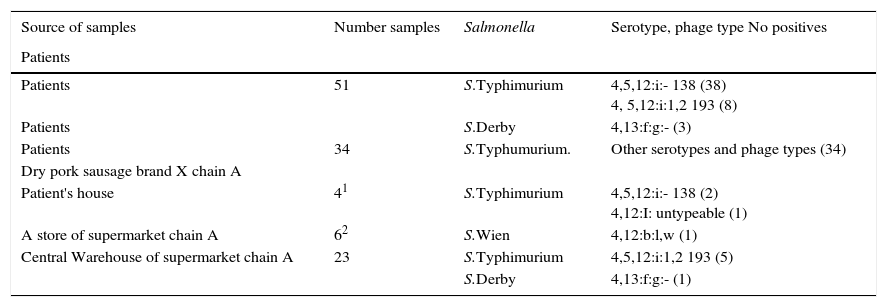

The study (Table 6) included 49 patients with S.Typhimurium (monophasic variant 4,5,12:i:-, and biphasic 4,5,12:i:1,2) and phage type 138 (38 cases), phage type 193 (8 cases), and S.Derby (3 cases), isolated from 47 fecal culture, a blood culture, and a urine culture. A further 34 patients were positive for S.Typhimurium phage types 104b (10 cases), phage type 21 (4 cases) phage type U302 (2 cases), phage type U311 (2 cases), phage type 110 (1 case), phage type 195 (1 case), phage type 161(1 case), and for monophasic S.Typhimurium untypable by phage typing (13 cases); these isolates were obtained from fecal cultures. All isolates from humans presented resistance to ampicillin and were sensitive to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, cefotaxime, cotrimoxazole, and ciprofloxacin.

Microbiologic results of samples from patients and foods.

| Source of samples | Number samples | Salmonella | Serotype, phage type No positives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | |||

| Patients | 51 | S.Typhimurium | 4,5,12:i:- 138 (38) 4, 5,12:i:1,2 193 (8) |

| Patients | S.Derby | 4,13:f:g:- (3) | |

| Patients | 34 | S.Typhumurium. | Other serotypes and phage types (34) |

| Dry pork sausage brand X chain A | |||

| Patient's house | 41 | S.Typhimurium | 4,5,12:i:- 138 (2) 4,12:I: untypeable (1) |

| A store of supermarket chain A | 62 | S.Wien | 4,12:b:l,w (1) |

| Central Warehouse of supermarket chain A | 23 | S.Typhimurium | 4,5,12:i:1,2 193 (5) |

| S.Derby | 4,13:f:g:- (1) |

1Open packing; 2Close packing.

Two S.Typhimurium isolates in brand X dried pork sausage from the household of two patients and one Salmonella spp in the same food from a store of supermarket chain A were isolated by the Public Health Microbiology Laboratory in Castellon, and 6 Salmonella spp were isolated in 23 samples of brand X dried pork sausage in the central warehouse of supermarket chain A in Valencia by the Microbiology Laboratory of the Valencia Public Health Center.

Serotyping and phage-typing of Salmonella isolates from brand X dried pork sausage (Table 6) found the following:

- -

In 2 samples from patients’ household monophasic S.Typhimurium (4,5,12:i:-) phage type 138 and monophasic S.Typhimurium (4,12:i:-) untypable, respectively.

- -

In a sample from a store of supermarket chain A in Castellon: S.Wien (4,12:b:l,w)

- -

In 6 samples from the central warehouse of supermarket chain A in Valencia, 5 S.Typhimurium (4,5,12:i:1,2) phage type 193, and one of S.Derby (4,12:f,g:-).

The analysis of the genetic relationship of the food and human monophasic Typhimurium phage type 138 isolates, Typhimurium phage type 193 isolates and Derby isolates showed an identical profile confirming that isolates belonging to the same serotype were the same strain.

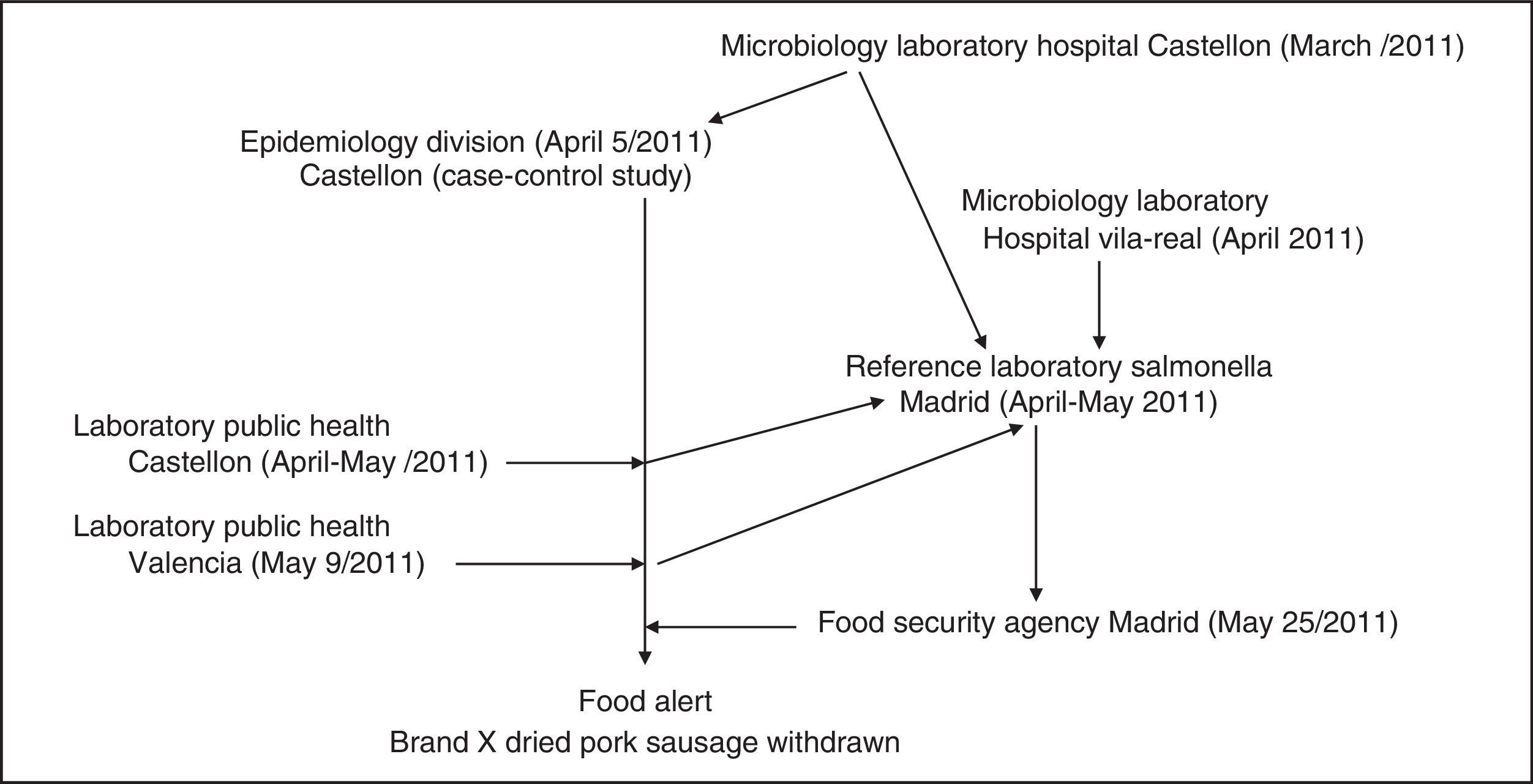

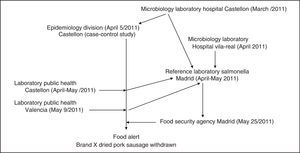

Control and prevention measuresOn 9 May 2011, the Health Authority of the autonomous region of Valencia was informed of the outbreak and the results of the case–control studies. The implicated food had only been distributed in the Autonomous Community of Valencia. On 18 May samples of brand X dried pork sausage were collected from the central warehouse of the supermarket chain A in the city of Valencia. On 25 May 2011, following the 5 positive S.Typhimurium(4,5,12:i:1,2) phage type 193, and one of S.Derby (4,12:f,g:-) from 23 samples and the results of the pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, a national level food alert was issued by the Spanish Food Security Agency, and the food was withdrawn from the chain A.9 After this withdrawal no new cases of gastroenteritis associated with the outbreak were found Figure 2 shows participating centers and chronology of the outbreak.

The Health Authority of the Autonomous Community of Aragon carried out the investigation in the factory where the implicated food was produced, a town in the province of Teruel, in Aragon, which borders on Castellon province. The measures of control and prevention included suspending production and immobilization and destruction of the implicated food (44000 kilograms), revision of the production program, and other complementary measures to prevent reoccurrence of this situation. The factory also introduced several measures including training for the abattoir staff, cleaning, and improvement to the hygiene of abattoirs and pens. The cause of the outbreak was attributed to an increase in production that exceeded the abattoir and the factory system's capacity and the underestimation of the survival of the Salmonella in the implicated food.

DiscussionThe results indicated that the outbreak was caused by several isolates of S.Typhimurium and S.Derby, and the source of infection was brand X dried pork sausage and the microbiological surveillance alerted on the outbreak. The matched case–control studies allowed the food to be identified and the microbiologic results confirmed the source of infection. Following the intervention, to withdraw the implicated food, no new cases associated with the consumption of this food occurred.

The second matched case–control study found associations between the gastroenteritis and the consumption of brand X dried pork sausage together with contact with diarrhea patients, suggesting that all cases came from the same outbreak. The isolate of several Salmonella phage types in the brand X dried pork sausage also lens support to this claim. In addition, the time of occurrence and the clinical symptoms suggest the same source of infection.

The number of patients affected by the outbreak was probably higher than the number reported, considering that only the cases were the patients with a microbiological culture and probably with more severe symptoms. A study by the Epidemiology Division into the incidence of gastroenteritis patients in the General Hospital Emergency Service of Castellon found an increase in the number of patients in the period March-April 2012.In addition, 13 controls were excluded by gastroenteritis symptoms and 4 of whom had the consumption of brand X dried pork sausage as a risk factor. An incidence rate of 2.3%, 4 cases and 177 controls (164 included and 13 excluded) associated with this consumption, was estimated.

The high incidence in children, median 4 years, and old people may be associated with the possible low concentration of Salmonella in the food vehicle together with low body mass and the immature immunity in children and defective immunity in old people. The clinical symptoms were compatibles with severe gastroenteritis and the presence of blood in feces was frequent. The period of incubation was not calculated, however, it could have a range of 3 to 7 days. Antibiotic resistances of the Salmonella strains were small when comparisons with other S.Typhimurium were made.5

Our knowledge, this outbreak is the first of monophasic S.Typhimurium associate with the consumption of dried pork sausage reported in Spain and very recent an outbreak of monophasic S.Typhimurium phage type 138 with homemade chorizo as food vehicle of transmission was been occurred in Basque Country.10 In addition, consumption of chorizo like sausage, imported from Spain, has been implicated in an outbreak of S.Typhimurium in Denmark.11 In an international context, some S.Typhimurium outbreaks have been associated with the consumption of pork in the form of salami sticks in Great Britain,12 salami products in Denmark,13 Italian salami in Sweden,14 traditional pork salami in Italy,15 and pork meat in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.16 These outbreaks have many similar characteristics to the outbreak reported here: the young medians age of patients’ age, the implicated food is ready to eat and it is consumed raw, the outbreaks tend to occur in spring, the severity of the infections with a high frequency of fever, presence of blood in stools, and frequent hospitalizations.

The Salmonella that caused the outbreak included monophasic S.Typhimurium phage type 138, S.Typhimurium phage type 193, and S.Derby; S.Wien was only isolated in food. The reservoir of these strains is the pig.17 In Europe, monophasic S.Typhimurium, is considered to be a potential and emergent risk for humans through the consumption of pork18 and some outbreaks of monophasic S.Typhimurium had been reported by several Europe Union countries such as France, where two outbreaks occurred with 447 patients and dried pork sausage as the likely vehicle of infections19–20 and Luxemburg with one outbreak and 133 patients with the consumption of pork meat as the suspected vehicle.21 In Germany outbreaks of this variant have been detected during 2006–2008.22 In France, an outbreak with 554 cases of the same variant in 4 schools was associated with the consumption of beef burger.23 In Italy, an outbreak of this variant was found associated with a cook pork product.24 It has been postulated that there are other animal reservoirs of this monophasic variant apart from pigs, such as chickens and turtles.25

The source of infection could find by the isolate of Salmonella in the brand X dry pork sausage and in samples from dried pork sausages in the warehouse of supermarket chain A. Monophasic and biphasic S.Typhimurium were isolated indicating that the contamination could have occurred at the factory during the dried pork sausage production, and that this contamination was elevated because three Salmonella strains were implicated. The production of brand X dried pork sausage was carried out in a town in Teruel province and the Aragon Health Authority found evidence of the cause of the outbreak in the producer. In addition, a recent study a herd-based survey of pigs in Aragon that including Teruel province, found Salmonella spp prevalence in the 31% of animals and in the 94% of herds.26 Samples were taken from mesenteric lymph nodes at the time of slaughter, and monophasic varaiant S.Typhimurium 4,[5], 12:i:- was the first prevalent serotype.26 Other serological survey in pigs in Aragon27 found high prevalence of the salmonellosis. The more important risk factors associated with the salmonellosis were farms without rodent control, long period of fattening, and farm with finishing pigs.26

The Surveillance of Salmonella was decisive detecting and controlling Salmonella outbreaks, considering that salmonellosis was not a notifiable disease in Spain in 2011. Pediatricians and generalist practitioners were unable to detect the outbreak. However, study of etiologic agents of gastroenteritis in fecal cultures, allowed the Microbiology Laboratory of Castellon General Hospital to detect the possibility of an outbreak in a short period of time. In addition, matched case–control studies found the source of the outbreak, and the characterization of the isolates by sero-typing, phage-typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis confirmed the source of the outbreak; the control measures were also effective. Several health institutions cooperated to control of the outbreaks (primary health care, microbiology laboratories, hospitals, and public health authorities).

The limitations of our study are as follows: the attack rate was not estimated, the magnitude of the outbreak could not be known, and the incubation period could not be estimated. In addition, some recall bias has occurred as a result of the study design, although reports about the outbreak appeared in the media once it was over. No chemical analyses of this food were carried out to learn how the Salmonella was able to survive in the food.12

Conclusions: The study revealed brand X dried pork sausage as the food vehicle of the outbreak and the cooperation of various health institutions enable it to be controlled and further spread prevented.

Conflict of interestNone conflict of interest by the authors.

We thank the patients, controls and their families for their cooperation in the control of this food-borne outbreak.