Inhibition of prejudice appears to be more problematic for older adults, hence the need to develop programs to reduce intergroup bias at later stages in life. Perspective taking was analyzed in this study, as one of various cognitive strategies that have been shown to reduce such bias. Data on a sample of 63 Spanish participants with a mean age of 64.1 years was gathered after an intervention based on mental imagery, aimed at reducing explicit prejudice. A wide array of variables was measured (personality traits, values, empathy, and attribution) which may moderate effectiveness in perspective taking. Despite no main effect was found, effects due to interaction of perspective taking found in OLS regression analysis revealed that perspective taking based intervention was effective for some older adults, particularly those who had low scores on agreeableness, empathy, and universalism, and high scores on conformity. The conclusions suggest that perspective taking might be successfully applied to some profiles of older people albeit it is not as strong and transferable strategy as it used to be thought.

La inhibición del prejuicio resulta más problemática en personas mayores, de lo que se deriva la necesidad de desarrollar programas que reduzcan el sesgo intergrupal en los estadios avanzados de la vida. En el presente estudio se analizó la toma de perspectiva como una de las estrategias capaces de reducir este tipo de sesgo. Se recogieron datos en una muestra de 63 participantes españoles con una edad media de 64.1 años, en la que se implementó una intervención basada en imaginería mental, dirigida a la reducción del prejuicio. Asimismo, se midieron diversas variables que podían modular la efectividad de la toma de perspectiva (personalidad, valores, empatía y atribución). Aunque no se encontró ningún efecto principal, los debidos a la interacción de la toma de perspectiva y los moduladores, hallados en el análisis de regresión por mínimos cuadrados ordinarios, revelaron que la intervención basada en la inducción de toma de perspectiva fue efectiva en determinadas personas mayores, particularmente en aquellas que puntuaron bajo en amabilidad, empatía y universalismo, y alto en conformismo. En las conclusiones se sugiere que la toma de perspectiva podría ser aplicada con éxito en determinados perfiles de adultos mayores, aunque no se trata de una estrategia tan potente y transferible como se pensaba.

Intergroup prejudices continue to have an extensive presence in all societies (Bodenhausen & Richeson, 2010). One of the most pervasive social biases is the one held about the aging and the older adults (e.g., Bennet, & Gaines, 2010; Cuddy, Norton, & Fiske, 2005; Hummert, 2011; Nelson, 2002, 2009; Kornadt & Rothermund, 2011; Triguero, Maciel, & Bezerra, 2007; Wachelke & Contarello, 2010). At the same time, the elderly are agents of bias. Firstly, this is made evident when they incorporate the extended social prejudice about their ingroup, having a relevant influence on themselves (Bennett & Gaines, 2010; Coudin & Alexopoulos, 2010; Hummert, 2011; Koher-Gruhn & Hess, 2012; Palacios, Torres, & Mena, 2009). Secondly, citizens of an advanced age do not only self-stigmatize, but also may contribute to the spread of prejudices towards other social groups, and higher levels of bias have been detected in them more so than in other groups (e.g., Hippel, Silver, & Lynch, 2000). However, like the rest of the population, elderly people are destined to live in an increasingly diverse society, which is why it is recommendable that they too have opportunities to move towards fairer evaluations of other citizens and groups with whom, to some extent, they must share their lives.

Responding to the interest in eradicating prejudices, socio-scientific research is increasingly concerned with evaluating the effectiveness of different types of actions aimed at the reduction of intergroup bias. ‘Perspective taking’ is one of the cognitive social types of techniques studied in this context. It is reviewed afresh in this article, to study its usefulness in a sample of older people, and to explore possible individual differences linked to the effectiveness of the strategy.

Prejudices in the elderlyThere are numerous psychosocial and sociological survey-based investigations that show a positive relation between age and prejudice in the adult population in North America and in Europe (see Pettigrew, 2006, for a review). Likewise, stereotyping and prejudice in older people have been compared with the same phenomena in young people (Gonsalkorale, Sherman, & Klauer, 2009; Hippel et al., 2000; Radvansky, Copeland, & Hippel, 2010; Stewart, Hippel, & Radvansky, 2009). Thus, Hippel et al. (2000) found in a sample of 36 young adults (M=21.2 years) and 35 elderly adults (M=80.2 years) that the latter displayed a lower conscious capacity for inhibition than the former, and that this capacity was found to be associated with levels of stereotyping and prejudice, which were higher among older adults. Stewart et al. (2009) established differences between young and elderly adults, but this time in relation to their automatic prejudice. They also confirmed that the cause was due to less automatic control (i.e., less preconscious inhibitory control) being exercised by the latter over their prejudiced associations. The work of Gonsalkorale et al. (2009) may be mentioned among other comparative studies that have arrived at a similar conclusion. These authors, who studied automatic race bias in older and younger people, analyzed data collected with the Implicit Association Test in a sample of 15,752 white individuals aged 11–94, and found that the activation of the association between “White” and “pleasant” significantly decreased with increasing age between the 21–30 and 51–60 age groups, and did not increase in older groups (61–70, and 71+). This evidence did not support the hypothesis that older adults have more biased associations than younger people. Instead, the effort to prevent automatically activated associations from influencing behavior, that was another parameter estimated (i.e., overcoming bias), decreased with age, leading to higher final IAT effects. This latter result supports the inhibitory deficits account. Radvansky et al. (2010) reached a similar conclusion in two experiments (plus a third control experiment), using a different task (i.e., stereotypic inferences drawn during the comprehension of narrative texts) and different measures (i.e., recognition and lexical decision times) that were completed by 71 young participants aged 18–25 (M=19.1), and 48 older adults aged 60–88 (M=72.1) in experiment 1, and 48 people in each of the two age groups in experiment 2 (Myoung=19.6, range = 19–23; Mold = 71.1, range = 60–83). Older adults drew stereotypic inferences to a greater extent than younger adults in the memory task, and this was likely due to a lesser inhibitory activity in the processing of information: older participants were faster than younger individuals to respond to stereotype-consistent probes in a lexical decision task, suggesting that they ineffectively inhibited the stereotypic information while young people were able to suppress it after it was activated by stories previously read. The common conclusion of all these studies is that older adults appear more prejudiced than younger people. However, this does not necessarily mean that they are more biased, but that they show their prejudices in their behaviors to a greater extent than younger individuals do.

It would appear that control over inhibition of the self-perspective figures among the abilities that undergo some decline at an older adult age (Bailey & Henry, 2008); a limitation that makes part of the generalized reduction of executive cognitive functions that has been detected in elderly people, in addition to self-regulatory failures of a social nature which, jointly, make it more difficult for those people to develop an adaptive behavior in interpersonal contexts (Henry, Hippel, & Baynes, 2009).

Perspective takingPerspective taking is the cognitive process of trying to understand the world from another person's point of view, or undertaking to put oneself in another's shoes. This process has been used in research as a strategy for prejudice reduction, implementing methods based on inducing participants to take the view of a stereotyped group member, and to imagine themselves thinking, feeling, and behaving as the other individual does in his/her particular living conditions. As a result, participants are supposed to become more “otherlike” through the cognitive approximation between the self and members of the stereotyped group, and between the ingroup and the outgroup.

Most of the cognitive research into this strategy has taken place over the last decade (Aberson & Haag, 2007; Epley, Keysar, Boven, & Gilovichm, 2004; Epley, Morewedge, & Keysar, 2004; Galinsky, 2002; Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky, Ku, & Wang, 2005; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Galinsky, Wang, & Ku, 2008; Hillman & Martin, 2002; Ku, Wang, & Galinsky, 2010; Shih, Wang, Bucher, & Stotzer, 2009; Todd, Bodenhausen, Richeson, & Galinsky, 2011; Todd, Galinsky, & Bodenhausen, 2012; Vescio, Sechrist, & Paolucci, 2003; Weyant, 2007) and, among the evinced effects, is a more positive evaluation of stereotyped members and of the same minority groups, less expression of stereotypical content, less hyperaccessibility of stereotyped representations, and a better social coordination, with accessibility to the self-concept acting as a mediating factor (Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Galinsky et al., 2005, 2008; Ku et al., 2010).

Galinsky et al. (2008) contend that not only is the self applied to the other, but that the other is included in the self, in such a way that those taking the perspective of a stereotyped group member will describe themselves more in terms of the stereotype and will even develop stereotypical behaviors. Whereas the first studies by Galinsky and his team (2005; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000) showed that the overlap between cognitive representation of the self and of the other lead to a decline in stereotyping and prejudice, the effects of a later works bear more relation to social coordination (Galinsky et al., 2008; Ku et al., 2010). In other words, perspective taking strengthens mimicry (i.e., the tendency of the self to assimilate other people's traits), which functions as a heuristic device to facilitate social ties.

In fact, an ironic effect occurs, because stereotyping and prejudice decrease as a consequence of an egocentric act: activation of the self-concept (Galinsky & Ku, 2004). Egocentrism would only be overcome at a second stage of the cognitive process of adopting the perspective of other individuals: in the first place, a person will try to adopt the perspective of the other through an initial strategy of anchoring it in his or her own perspective, and only afterwards an adjustment mechanism would come into play that would serve to explain the differences between themselves and others (Epley, Keysar et al., 2004; Epley, Morewedge et al., 2004). In accordance with the existence of a first egocentric stage, Galinsky and Ku (2004) showed moderation exercised by chronic and temporal self-esteem: perspective taking would be more effective between those characterized by high levels of self-esteem. Likewise, the work of Vescio et al. (2003) may be highlighted in relation to the clarification of the mediational role of some variables, which confirmed the operation of a further two mechanisms that mediate between perspective taking and its effects: empathic feelings and attributions. Taking this study together with those of Galinsky (Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Galinsky et al., 2005, 2008; Ku et al., 2010; Todd et al., 2012), it could be concluded that approximations already exist to knowledge on certain mediators and moderators that are operative in the perspective taking strategy, although these must be broadened with new contributions to help understand the ideal conditions under which the intervention is most effective.

This studyThe impact of perspective taking on the reduction of explicit prejudice is analyzed once again in this study, using the classic manipulation proposed by Galinsky and Moskowitz (2000), though in this case with a sample of older adults —although not of a very advanced age— and various moderations are explored, given the importance that individual differences have on the effectiveness of prejudice reduction strategies (Hodson, 2009). More specifically, data were gathered on a dependent variable (explicit prejudice); on a further two (empathy and attribution) whose regulatory capacity between perspective taking and prejudice has already been established (Vescio et al., 2003); and on several variables relating to personality (extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness), and a set of values (universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation and self-direction), whose relations to prejudice have to some degree been evinced (see the negative correlation between prejudice and agreeableness, openness to experience, and extraversion, tested by Ekehammar and Akrami [2003, 2007; see also Akrami, Ekehammar & Bergh, 2011], Flynn [2005], and Sibley and Duckitt [2008]; and the positive relation between prejudice and the importance of self-enhancement and conservation values, documented in Feather and McKee [2008]), but not their moderating intervention on the effects of perspective taking. Gender was not recorded because it does not explain the variability found in data on prejudice (e.g., Amodio & Devine, 2006; Castillo, 2005; Blair, Ma, & Lenton, 2001).

In summary, two expectations were proposed: 1.perspective-taking strategy would reduce levels of explicit prejudice; and 2.several moderators would affect the effectiveness of perspective taking on the reduction of prejudice (particularly, empathy, attribution, extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, and a set of values: universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation and self-direction).

MethodDesign and participantsA post-test only design with an experimental condition (a perspective taking task) and a control group (the same task, but without the instructions aimed at inducing the participants to take the perspective of the target person) was carried out. The sample included 70 older adults, aged 56 to 75, enrolled in the University Program for Elderly People at the University of Burgos (Spain), aimed at achieving non-professional, ethical, and civic goals. Data on seven participants were excluded from the study due to different types of human errors in the execution of the tests; consequently, the final sample was made up of 63 university students with an average age of 64.13 (SD = 4.79) and with a very equal gender balance (33 women and 30 men). None of the participants belonged to the minority group —Moroccans— which was used to measure prejudice (bias against Moroccans is widespread in Spanish culture, although a similar circumstance is found throughout Europe [Strabac & Listhaug, 2008]).

MeasuresThe three personality factors (agreeableness, openness to experience, and extraversion) were measured with 36 of the 60 items that comprise the Neo-Five Factor Inventory (Neo-FFI), which is a shortened version of the NEO Personality Inventory-R (NEO PI-R) (Costa & McCrae, 1992). The Spanish version used in this study was the one adapted by Cordero, Pamos and Seisdedos 2002), who reported alpha reliability coefficients of .83 for agreeableness, .82 for openness to experience, and .84 for extraversion. The instrument uses a 5-point Likert response format (1 = completely disagree and 5 = completely agree).

The instrument used for data collection on values was based on the theory of basic human values of Schwartz (1992). It is taken from the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ) (Schwartz, Melech, Lehmann, Burguess, & Harris, 2001) in order to measure the 10 values of that theory (universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation and self-direction). Specifically, in this study we took the 12-item version previously used by Basabe, Páez, Aierdi, and Jiménez-Aristizabal (2009), which was based on the collection of the best items of a 40-item Spanish version adapted by Zlobina (2004), with the following reliability coefficients for the two poles of each of the two dimensions that group values: .81 for Self-transcendence (universalism and benevolence), .78 for Conservation (tradition, conformity, and security), .74 for Self-promotion (power, achievement, and hedonism), and .74 for Openness to change (stimulation and self-direction) (see the information about the quality of the adapted version in Basabe, Valencia, & Bobowik, 2011). Participants were asked about the extent to which the person described in each of the 12 items looked like them, and had to give their responses on a 6-point scale (1 = not like me at all and 6 = very much like me).

Empathy and attribution were measured with scales designed on an ad hoc basis, although the format was similar to that used by Vescio et al. (2003). In the case of the first variable, participants were asked to what extent the Moroccan person that appeared in a series of twenty on-screen images inspired an emotion in them (sympathetic, compassionate, warm-hearted, tender, and moved).The test was therefore made up of twenty items (four for each emotion) and the participants responded on a 7-point scale (1 = none and 7 = extremely). Reliability was very satisfactory with a Cronbach's alpha of .87.

With regard to the last potentially moderating variable (attribution), a brief on-screen narrative presented the story of a Moroccan immigrant with a positive outcome, after which the participants were asked to judge the relevance that various factors might have had in the success of the immigrant. Five items pointed to internal factors (e.g., “It is important to have an open and optimistic attitude towards life in order to do what Hassan has done”), and a further five to external factors (e.g., “He has probably received public funds to set up his business, as well as tax benefits that would not have been available to him in his home country”). The response had to be given on a seven-point scale (1 = extremely irrelevant and 7 = extremely relevant). Differential attribution was calculated by subtracting average internal attribution from average external attribution. Thus, a positive score indicated a tendency by the participant to attribute the immigrant's achievements to external causes, whereas a negative score reflected a preference for attribution to internal causes. The internal consistency was moderate, α = .69.

The dependent variable, explicit prejudice, was evaluated with McConahay's Modern Racism Scale (McConahay, 1986; McConahay, Hardee, & Batts, 1981). The Spanish version used in this study was the one adapted by García, Navas, Cuadrado and Molero (2003), who reported an alpha coefficient of .72. This instrument, which includes a seven-point response scale (1 = completely disagree and 7 = completely agree), measures the cognitive component of racial attitudes in a way that is less susceptible to the bias of social desirability than more conventional scales (García et al., 2003).

ProcedureThe experimental manipulation was similar to the one introduced by Galinsky and Moskowitz (2000), and repeated in some other studies with very small variations (Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky et al., 2008; Ku et al., 2010; Todd et al., 2011, 2012). In this now classical procedure, the task consists of writing a narrative essay in which participants of experimental and control groups have to describe a day in the life of a stereotyped group member shown in a picture on the computer's screen. The manipulation is robust –it has been proved to be effective in the cited previous studies, so that it was reproduced in the current experiment.

Having completed the random distribution between the two design conditions (experimental and control), 20 participants at a time (except for the last group, which numbered ten participants) were invited to attend the computer laboratory, where PCs that processed the manipulation and the tests were equipped with Intel Dual Core E2140 1.60 Ghz processors, running on Windows XP operating systems. MediaLab software (version 2006.2) from Empirisoft was used for assisting in manipulation and data collection. Once the participants were seated in front of the screen, the experimenter explained that it would be interesting to know how they imagined daily life events from visual information, and a black and white picture of a Moroccan man's face was then displayed on screen, accompanied by written instructions. All participants were asked to imagine a day in the life of the person in the image, and write a three-minute description about that person on the piece of paper next to the keyboard. They were also asked to write fluidly and not to stop to think or to organize what they had already written. Additional instructions were given to the experimental participants to adopt the perspective of the person in the photograph: “Please put yourself in the shoes of the person in the image, and try to see the world through his perspective and from his point of view. Try to imagine how this Moroccan immigrant might feel.”

When the participants had read the instructions, they pressed the space bar and were asked to begin writing. Once the time had elapsed, a flickering screen displayed a message to inform them that their time was over. Ten seconds later, the presentation of on-screen instructions for the first test began. The order in which the instruments were applied was as follows: (a) Neo-FFI: Extraversion, Openness to Experience and Agreeableness; (b) The reduced version of the Portrait Values Questionnaire; (c) McConahay's Modern Racism Scale; (d) Empathy test; and (e) Attribution test. After the session had drawn to a close, participants were informed about the true nature of the study.

ResultsLevel of prejudice and main effect of perspective takingThe global mean for explicit prejudice (M=3.89, SD=1.15) appears to be indicating slight agreement with the statements that uphold racist attitudes (‘4’ being the theoretical mean of the 7-point scale used), but, contrary to what was expected, it was not possible to reject the equivalence between experimental (M=3.79, SD=1.16) and control participants (M=3.98, SD=1.15), t (61) = -.65, p=.52. Therefore, perspective taking failed to explain any variation in the level of explicit prejudice.

Moderating effectsTable 1 shows the means and standard deviations corresponding to the total sample and to each of the two groups (experimental and control) in the 15 variables that were tested as potential moderators between perspective taking and prejudice. Two-tailed t-tests were used to examine the difference between the group means in each of the variables. All tests results were non significant (ps > .05).

Basic statistics for the variables measured as potential moderators of the perspective taking-prejudice relation

| Variables | Total sample | Experimental group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Personality factors | Extraversion | 3.58 | 0.48 | 3.64 | 0.54 | 3.52 | 0.42 |

| Agreeableness | 3.50 | 0.53 | 3.51 | 0.59 | 3.48 | 0.47 | |

| Openness | 3.57 | 0.45 | 3.57 | 0.45 | 3.57 | 0.45 | |

| Values | Universalism | 4.74 | 0.81 | 4.61 | 0.64 | 4.86 | 0.64 |

| Benevolence | 4.87 | 0.85 | 4.73 | 1.06 | 5.02 | 0.57 | |

| Tradition | 3.21 | 0.99 | 3.08 | 0.73 | 3.34 | 1.18 | |

| Conformity | 2.80 | 1.16 | 2.85 | 1.12 | 2.75 | 1.22 | |

| Security | 3.55 | 1.24 | 3.26 | 1.18 | 3.83 | 1.25 | |

| Power | 3.09 | 1.05 | 2.98 | 1.06 | 3.19 | 1.05 | |

| Achievement | 3.96 | 1.21 | 3.73 | 1.20 | 4.19 | 1.20 | |

| Hedonism | 4.59 | 0.97 | 4.48 | 0.93 | 4.69 | 1.02 | |

| Stimulation | 4.54 | 1.00 | 4.71 | 0.92 | 4.38 | 1.05 | |

| Self-direction | 4.97 | 0.84 | 4.92 | 0.84 | 5.02 | 0.85 | |

| Empathy | 4.21 | 1.15 | 3.95 | 0.98 | 4.47 | 1.26 | |

| Differential Attribution | −2.59 | 1.20 | −2.54 | 1.29 | −2.64 | 1.12 | |

Note: M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation.

The correlations among all the variables measured are included in table 2. Particularly, concerning the dependent variable, the pattern of associations is consistent with previous findings: prejudice correlates negatively with openness to experience (p < .05) and agreeableness (p < .05), while a trend is observed toward its positive association with values of power and achievement, as well as a negative correlation with empathy-marginally significant coefficients were found (p < .10).

Correlations among variables: Personality factors (1–3), values (4–13), empathy (14), attribution (15), and prejudice (16) (N=63)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Extraversion | _ | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Agreeableness | .28* | _ | |||||||||||||

| 3. Openness | .09 | .23† | _ | ||||||||||||

| 4. Universalism | .07 | .40** | .30* | _ | |||||||||||

| 5. Benevolence | .16 | -.04 | .10 | .20 | _ | ||||||||||

| 6. Tradition | .06 | .11 | -.28* | .07 | .16 | _ | |||||||||

| 7. Conformity | -.03 | -.11 | -.35** | -.26* | -.16 | .39** | _ | ||||||||

| 8. Security | -.09 | -.13 | -.09 | .12 | .10 | .38** | .39** | _ | |||||||

| 9. Power | .04 | -.09 | -.20 | -.09 | -.01 | .31* | .40** | .51*** | _ | ||||||

| 10. Achievement | .04 | -.16 | -.01 | -.09 | .05 | -.11 | .09 | .27* | .47*** | _ | |||||

| 11. Hedonism | .32* | .08 | .02 | .06 | .27* | .14 | -.09 | .34** | .21† | .12 | _ | ||||

| 12. Stimulation | .48*** | .10 | .17 | -.03 | -.08 | .09 | -.10 | .03 | .02 | -.04 | .51*** | _ | |||

| 13. Self-direction | -.01 | -.02 | .39** | .32* | .24† | .08 | -.26* | .08 | -.06 | -.06 | .12 | .05 | _ | ||

| 14. Empathy | .26* | .29* | .18 | .27* | .22† | .02 | .14 | .21† | -.04 | .01 | .18 | .15 | .09 | _ | |

| 15. Attribution (differential) | -.04 | -.22† | -.20 | -.29* | .21† | .12 | .12 | -.06 | .05 | .10 | .06 | -.20 | -.09 | -.07 | _ |

| 16. Prejudice | -.16 | -.27* | -.25* | .09 | .17 | .15 | .08 | .18 | .23† | .22† | -.01 | -.21† | -.02 | -.24† | .02 |

The critical analysis carried out to verify the second set of expectations was based on moderation. This analysis was performed with MODPROBE, a computational aid for SPSS (and SAS), developed by Hayes and Matthes (2009) for probing single-degree-of-freedom interactions in OLS and logistic regression (see also Hayes, 2013). The OLS regression effects due to the interaction between the predictor (condition: perspective taking vs. control) and each of the 15 moderators measured in the study are shown in table 3.

Ordinary least squares regression effects due to the interaction between the predictor and the moderators, R2 for the complete model, and R2 increase due to interaction (when p < .05)

| Moderators interacting with the predictor (condition) | b | SE | t | p | R2(change in R2) | F (3,59) (F for the change) | p (p for the change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | 0.39 | 0.63 | 0.62 | .537 | |||

| Openness to experience | 0.17 | 0.64 | 0.26 | .797 | |||

| Agreeableness | 1.21 | 0.53 | 2.27 | .027 | .15 (.07) | 3.57 (5.16) | .019 (.027) |

| Empathy | 0.55 | 0.25 | 2.22 | .030 | .15 (.07) | 3.49 (4.95) | .021 (.030) |

| Attribution | −0.04 | 0.25 | −0.17 | .868 | |||

| Self-direction | −0.12 | 0.36 | 0.35 | .728 | |||

| Power | −0.16 | 0.28 | −0.59 | .559 | |||

| Universalism | 0.87 | 0.38 | 2.28 | .026 | .09 (.08) | 2.02 (5.20) | .120 (.027) |

| Benevolence | −0.39 | 0.41 | −0.96 | .342 | |||

| Achievement | −0.12 | 0.24 | −0.49 | .625 | |||

| Security | −0.20 | 0.24 | −0.81 | .419 | |||

| Stimulation | −0.20 | 0.30 | −0.68 | .502 | |||

| Conformity | −0.58 | 0.24 | −2.34 | .023 | .10 (.08) | 2.14 (5.48) | .105 (.023) |

| Tradition | −0.15 | 0.34 | −0.45 | .652 | |||

| Hedonism | −0.03 | 0.31 | −0.10 | .924 |

Note: SE: Standard Error; t: t-test, used to test the null hypothesis that the interactions are equal to zero.

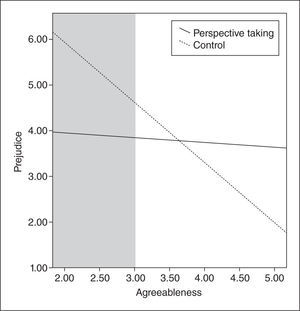

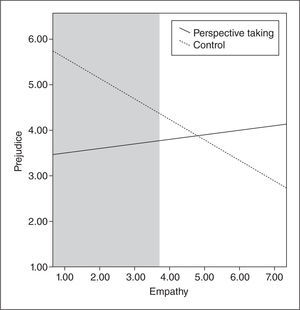

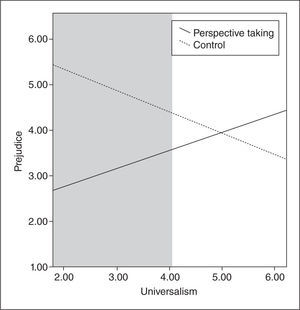

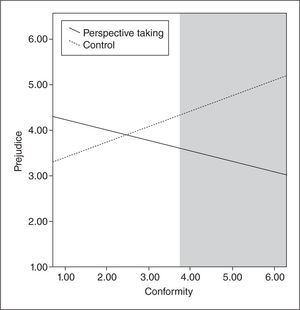

As can be seen, four moderators interact with the condition: agreeableness, b=1.21, t=2.27, p=.027, empathy, b=.55, t=2.22, p=.030, universalism, b=.87, t=2.28, p=.026, and conformity, b=-.57, t=−2.34, p=.023. Therefore the effect of the condition on explicit prejudice depends on the degree to which participants are agreeable, empathetic, universalist and conformist.

The conditional effects of the focal predictor (condition) at three different moderator values were computed in order to characterize the interaction. The selected values, as recommended by Hayes and Matthes (2009), were the sample mean (moderate position), and one standard deviation below (low position) and above (high position) the mean. It was found that among those who scored low on agreeableness, b=-.81, t (59)=−2.07, p=.042, empathy, b=-.97, t(59) = −2.46, p=.017, and universalism, b=-.90, t(59) = −2.08, p=.042, perspective taking had an effect on prejudice, but not among participants who scored on the mean or one standard deviation above the mean on these moderators. Conformity behaved differently: perspective taking was effective in participants who scored high on the moderator, b=-.86, t(59) = −2.16, p=.035.

The Johnson-Neyman technique was used to identify the range of values of the moderators where the predictor has a statistically significant effect (p < .05). Results yielded by MODPROBE showed that perspective taking predicted prejudice when participants scored below 3.03 on agreeableness (Magr=3.50, SD=.53), below 3.71 on empathy (Memp=4.27, SD=1.21), below 4.04 on universalism (Muni=4.74, SD=.81), and above 3.72 on conformity (Mcon= 2.80, SD=1.16). Regions of significance where the manipulation was effective are colored gray in figures 1 to 4. Participants who took the perspective of the immigrant and scored low on agreeableness, empathy, universalism, and high on conformity, informed about lower levels of prejudice than control participants with similar scores on the four moderators.

One possible alternative explanation of the moderator effects of agreeableness, empathy, universalism, and conformity on the perspective taking-prejudice relationship is that prejudice was uniformly high among people less agreeable, empathetic, and universalistic, and among those more conformist, while the dependent variable scores were homogeneously low among the participants more agreeable, empathetic, and universalistic, and among those less conformist. To examine this possibility, we divided the sample into four groups, using the quartiles, in any of the distributions of the four moderators, and calculated the variances of prejudice. However, Levene tests for the equality of the variances were non significant for the four moderators (p=.378 for agreeableness, p=.213 for universalism, p=.803 for conformity, and p=.275 for empathy). Thus, we may conclude that the moderator effects of agreeableness, empathy, universalism, and conformity are not due to ceiling or floor effects.

Figures 1–4 also suggest that the relation between prejudice and the moderators in the control group is not the same as it is in the perspective taking group. The correlations in the former group generally support previous findings, reaching significance in the case of agreeableness (rpre-agr= -.54, p < .01), empathy (rpre-emp = -.53, p < .01), and conformity (rpre-con= .36, p < .05) (no significant correlation was found between universalism and prejudice, rpre-uni= -.262). The results are very different in the experimental group, where none of the coefficients reached significance (rpre-agr = -.05, rpre-emp = .09, rpre-con = -.23, rpre-uni = .32).

DiscussionThe results suggest that perspective taking, as put into practice in this study, turned out to be a strategy of moderate effectiveness, in general terms, for the reduction of prejudice. This type of intervention would basically serve to control explicit prejudice in those older adults with a less sensitive and altruistic personality (agreeableness), less prone to affectively identify with the lives of others (empathy), less comprehensive and tolerant (universalism value), and in those people who show more restraint in their behaviors so as not to violate social norms (conformity value). In consequence, although a generalized positive effect of perspective taking on prejudice has not been evidenced, at least it has been confirmed that certain types of older adults benefit from adopting the point of view of an outgroup member. These results are particularly encouraging because they suggest that the strategy is useful for those in greatest need, where as it did not benefit more agreeable, empathetic, universalistic people, and those who were less conformist. In this way, our study joins the body of research that supports that some interventions to reduce prejudice are effective in people most prone to being prejudiced, as is the case of contact (e.g., Adesokan, Ullrich, van Dick, & Tropp, 2011). A more analytical review of the study's partial conclusions and the points that they raise is presented below.

In the first place, older people agreed slightly with the statements that upheld racist attitudes. This could be suggesting the possibility of a lower inhibition capacity on the part of participants in our sample with respect to the population average (Bailey & Henry, 2008; Gonsalkorale et al., 2009; Hippel et al., 2000; Stewart et al., 2009), bearing in mind that the Modern Racism Scale, when all is said and done, is a contaminated instrument due to the self-presentation motive (Schneider, 2004), and that low averages for prejudice towards Moroccans were found in earlier studies on Spanish samples that used this scale (García et al., 2003; Navas, 1998; Rojas, García, & Navas, 2003). Despite recent evidence in the literature on cognitive neuroscience having demonstrated the existence of control mechanisms that start to operate very early on in the process of the biased response, and that do so in an automatic manner without the participant being aware of them (Lieberman, 2007, 2010), the activation and codification of cues relating to race and gender occur even sooner in the automatic processing of the information (Ito, Urland, Willadsen-Jensen, & Correll, 2006).This fact, linked to self-regulatory failings in older people, would as a result position them in the middle of the response scale for the explicit prejudice test.

The following topic is even more crucial in this study: determination of the effectiveness of perspective taking at reducing intergroup bias. It had initially been thought that this type of strategy could be effective for the control of stereotyping and prejudice, as is evident from the research to date (Aberson & Haag, 2007; Epley, Keysar et al., 2004; Epley, Morewedgeet al., 2004; Galinsky, 2002; Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Galinsky et al., 2005, 2008; Hillman & Martin, 2002; Ku et al., 2010; Shih et al., 2009; Todd et al., 2011, 2012; Vescio et al., 2003; Weyant, 2007). In that regard, the results do not entirely support this prediction, despite having used a manipulation that is similar to the one performed by Adam Galinsky (Galinsky & Ku, 2004; Galinsky & Moskowitz, 2000; Galinsky et al., 2008; Ku et al., 2010; Todd et al., 2011, 2012). In general terms, the intervention is likely to have been neither capable of achieving the overlap between the self and the other, nor between the ingroup and the outgroup. Therefore, the self-concept, which appears as a mediator in the cognitive processing of information in a situation of perspective taking, appears to not have been activated in a generalized way among older adults affected by the intervention and, were it activated, it would not have produced the transition to the second phase of the model proposed by Epley and his colleagues (Epley, Keysar et al., 2004; Epley, Morewedge et al., 2004). The latter contends that an adjustment mechanism would come into play that would serve to explain the differences between participants and targets. An alternative or complementary explanation might argue that the persistence of the self-perspective is maintained as a consequence of the limited inhibitory control of older people (Bailey & Henry, 2008).

Simultaneously, our results suggest that it is necessary to replace the conclusion that perspective taking is globally ineffective by a certain partial effectiveness. In other words, there are conditions in which this strategy is useful to combat prejudice; the individual differences in this context being very relevant (Hodson, 2009). Among the moderations that have been demonstrated, the theoretical framework did anticipate the one that relates to empathy. The findings of Vescio et al. (2003) had pointed to empathy arousal as a useful mediation in the reduction of prejudice after a perspective-taking intervention. This study has extended the scope of action of empathy by studying its role as a moderator variable. In this latter role, not every older person takes advantage of perspective taking (a general mediational effect was found in Vescio's study), but only those who are less empathetic. An analysis of the mediation and moderation roles of empathy in the same study could provide a more complete picture in this area of research.

It should also be highlighted that some values are authentic regulatory factors of the effectiveness of perspective taking (Schwartz, 1994). It had already been established that value dimensions of self-transcendence and conservation are related to intergroup bias (Feather & McKee, 2008). Now the moderating roles of a self-transcendence value —universalism—and a conservation value —conformity— have also been proved in the field of prejudice reduction strategies. This study has provided a parallel innovation that presents a personality trait—even though the relation between prejudice and agreeableness has been previously demonstrated (Akrami et al., 2011; Ekehammar & Akrami, 2003, 2007; Flynn, 2005; Sibley & Duckitt, 2008)—as an effective moderator between perspective taking and prejudice.

These conclusions make this research both relevant and useful, since they may be used as the groundwork to draw up guidelines for the design of training programs directed at the control of intergroup bias in older participants. More particularly, it has been made clear that not all participants will potentially benefit from adopting the perspectives of outgroup members; therefore any program will need a selective filter that identifies the potential beneficiaries. Nevertheless, it is evident that our results should achieve greater consistency before considering the development of any type of application.

The scarce global effectiveness reached by perspective taking could be explained by the difficulty of transferring interventions from one cultural milieu to another, and even by theoretical frameworks that have been developed in contexts that differ from the application. In the final analysis, the social-cultural settings impact on the way in which prejudices develop (Teichman & Bar-Tal, 2008), and they may also determine the way in which bias can be eradicated or, at least, the extent to which its control is feasible (Pedersen, Walker, & Wise, 2005). This explanation would be supported by the problems of external validity that have been found in numerous studies directed at the reduction of prejudice (Paluck & Green, 2009). Consequentially, exploration of the transculturality of perspective taking will also have to continue, as a strategy for the reduction of prejudice in diverse settings.

FundingThis research was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Innovation, Spain (R&D Project SEJ2005-00331), and from the Government of Castile and Leon, Spain (R&D Project BU030A08).