Standard criteria for defining suboptimal response to disease-modifying treatment (DMT) in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) are lacking. Decision-making on how and when DMTs should be switched is challenging. The objective of the study was to identify areas of agreement on which and when specific assessments should be conducted to monitor patient response to DMT.

MethodsA survey comprising 54 statements in nine categories was drafted by eight MS experts after gathering insight during four previous meetings of a total of 25 MS experts. For each statement, results were classified as being in general agreement (≥66.6% responded “Strongly agree” or “Agree”) or general disagreement (≥66.6% responded “Strongly disagree” or “Disagree”).

ResultsThe survey was sent to 790 MS neurologists, 151 of whom participated (19%), and 98 (65%) completed it. General agreement and disagreement were reached for 45 and 2 statements, respectively, on different aspects of MS management, including treatment response, MS relapses, progression, disease activity measured by imaging and biomarkers, neuropsychological evaluation, brain volume loss, DMT switches due to lack of response and applicability to clinical practice.

ConclusionsThis study aims to provide guidance for the early identification of suboptimal response to DMT and for improving MS patient monitoring and treatment.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease of the central nervous system characterised by inflammation, demyelination, glial scar formation and axonal damage leading to varying degrees of neurological impairment. It causes episodes of neurological dysfunction lasting a few days or weeks (known as relapses), which tend to partially or completely resolve, especially in the early stages of the disease. With time, MS leads to progressive neurological impairment with or without relapses.1 The associated symptoms, disease progression and treatment response vary greatly,2 making the prognosis of individual patients uncertain. For this reason, the establishment of predictive and unified criteria to monitor treatment response might be useful to improve the clinical outcomes of MS treatments.

Since the launch onto the market of interferon beta (IFNβ) in 1993, attempts have been made to define suboptimal response criteria based on different predictive response factors, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), disability progression, relapses or a combination thereof.3–8 In 2004, the Canadian Multiple Sclerosis Working Group developed a series of recommendations based on the three parameters outlined above.3 The “Rio Score” proposed in 2009,8 which laid the foundations for the evaluation of treatment response, has been modified and refined in other cohorts of patients.6,7,9 Since then, the paradigm of MS has changed due to the availability of new disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) and a better understanding of MS pathology.

However, there are no standard criteria regarding the definition of suboptimal response, or, therefore, for when a switch in DMT should be considered. This is likely due to multiple factors, including the absence of highly predictive, widely used criteria with reasonable sensitivity and sensibility, heterogeneity in patient follow-up between centres, and a mismatch between clinical trials and real-life clinical practice.5 As a result, a high percentage of MS patients do not present adequate control of their disease activity while receiving DMT. In this context, the establishment of treatment response criteria is critical. The aim of this study was to establish general consensus among MS neurologists on the variables that should be evaluated to monitor response to DMT.

Material and methodsFig. 1 shows a schematic representation of the study methodology.

Development of the statementsFour meetings were held with a panel of 25 MS experts aimed at addressing the unmet needs in monitoring DMT response, including the definition of suboptimal response. The MS experts were neurologists with extensive experience in MS management who belong to the Group of Demyelinating Diseases of the Spanish Society of Neurology. Eight of them were then appointed to the Scientific Committee of the Study due to their active involvement in MS research studies. The Scientific Committee met on the 8th of March 2018 in Madrid, and, based on the insights gathered during the previous meetings, they approved the final version of the survey.

Rating of the statementsNeurologists with experience in MS (MS neurologist, hereafter) were invited to rate each statement of the survey using a digital platform. The survey included 54 statements grouped into nine categories: 1) assessment of treatment response, 2) relapses, 3) radiological activity, 4) disease activity measured by biomarkers, 5) disability progression; 6) brain volume loss (BVL), 7) neuropsychological aspects, 8) DMT switch due to lack of response; and 9) applicability in clinical practice. Each statement was rated on a 4-point Likert scale: “Strongly disagree”, “Disagree”, “Agree”, and “Strongly agree”. For the DMT switch due to lack of response category, the following three options were provided instead: “Maintain treatment”, “Switch to a treatment with a different mechanism of action but similar effectiveness”, or “Switch to a treatment with greater effectiveness”.

All responses were anonymous and were analysed regardless of whether the survey was partially or fully completed. Survey results were considered to be in general agreement when the sum of “Strongly agree” and “Agree” responses was ≥66.6% of the total responses. General disagreement was considered when the sum of “Strongly disagree” and “Disagree” responses was ≥66.6% of the total responses. There was no general agreement or disagreement when none of the above assumptions were fulfilled.

Subgroup analyses were performed according to: the type of hospitals where the neurologists work (tertiary versus other), the number of MS patients per month (<21 patients versus ≥21 patients), and availability of MS monographic consultation. In addition, a subgroup analysis was conducted according to the most represented Spanish regions (>5%).

ResultsAmong the 790 MS neurologists who received the survey, 151 from 16 Spanish regions participated (participation rate 19%); 98 (65%) completed the survey, and 53 (35%) completed it partially. Most of the neurologists worked in tertiary-level hospitals (67%), saw ≥21 MS patients per month (65%) and conducted monographic visits of MS 1 or 2 days a week (56%) (Fig. 2).

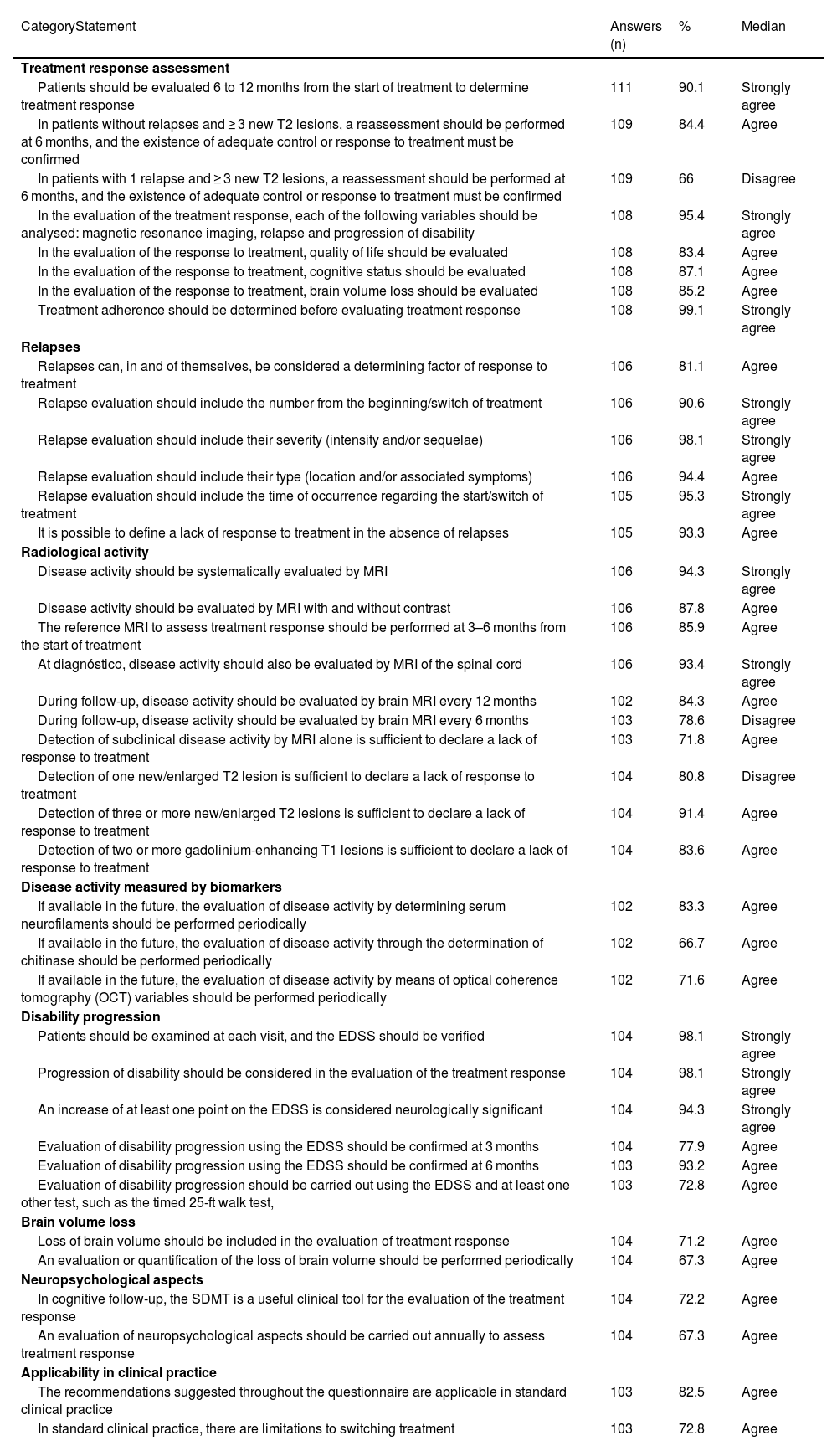

Here, we describe the general agreement or disagreement obtained for each statement. Tables 1 and 2 show these results. Table A.1. shows the survey results for statements where general agreement or disagreement was not achieved.

Survey results for statements where general agreement or disagreement was achieved.

| CategoryStatement | Answers (n) | % | Median |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment response assessment | |||

| Patients should be evaluated 6 to 12 months from the start of treatment to determine treatment response | 111 | 90.1 | Strongly agree |

| In patients without relapses and ≥ 3 new T2 lesions, a reassessment should be performed at 6 months, and the existence of adequate control or response to treatment must be confirmed | 109 | 84.4 | Agree |

| In patients with 1 relapse and ≥ 3 new T2 lesions, a reassessment should be performed at 6 months, and the existence of adequate control or response to treatment must be confirmed | 109 | 66 | Disagree |

| In the evaluation of the treatment response, each of the following variables should be analysed: magnetic resonance imaging, relapse and progression of disability | 108 | 95.4 | Strongly agree |

| In the evaluation of the response to treatment, quality of life should be evaluated | 108 | 83.4 | Agree |

| In the evaluation of the response to treatment, cognitive status should be evaluated | 108 | 87.1 | Agree |

| In the evaluation of the response to treatment, brain volume loss should be evaluated | 108 | 85.2 | Agree |

| Treatment adherence should be determined before evaluating treatment response | 108 | 99.1 | Strongly agree |

| Relapses | |||

| Relapses can, in and of themselves, be considered a determining factor of response to treatment | 106 | 81.1 | Agree |

| Relapse evaluation should include the number from the beginning/switch of treatment | 106 | 90.6 | Strongly agree |

| Relapse evaluation should include their severity (intensity and/or sequelae) | 106 | 98.1 | Strongly agree |

| Relapse evaluation should include their type (location and/or associated symptoms) | 106 | 94.4 | Agree |

| Relapse evaluation should include the time of occurrence regarding the start/switch of treatment | 105 | 95.3 | Strongly agree |

| It is possible to define a lack of response to treatment in the absence of relapses | 105 | 93.3 | Agree |

| Radiological activity | |||

| Disease activity should be systematically evaluated by MRI | 106 | 94.3 | Strongly agree |

| Disease activity should be evaluated by MRI with and without contrast | 106 | 87.8 | Agree |

| The reference MRI to assess treatment response should be performed at 3–6 months from the start of treatment | 106 | 85.9 | Agree |

| At diagnóstico, disease activity should also be evaluated by MRI of the spinal cord | 106 | 93.4 | Strongly agree |

| During follow-up, disease activity should be evaluated by brain MRI every 12 months | 102 | 84.3 | Agree |

| During follow-up, disease activity should be evaluated by brain MRI every 6 months | 103 | 78.6 | Disagree |

| Detection of subclinical disease activity by MRI alone is sufficient to declare a lack of response to treatment | 103 | 71.8 | Agree |

| Detection of one new/enlarged T2 lesion is sufficient to declare a lack of response to treatment | 104 | 80.8 | Disagree |

| Detection of three or more new/enlarged T2 lesions is sufficient to declare a lack of response to treatment | 104 | 91.4 | Agree |

| Detection of two or more gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesions is sufficient to declare a lack of response to treatment | 104 | 83.6 | Agree |

| Disease activity measured by biomarkers | |||

| If available in the future, the evaluation of disease activity by determining serum neurofilaments should be performed periodically | 102 | 83.3 | Agree |

| If available in the future, the evaluation of disease activity through the determination of chitinase should be performed periodically | 102 | 66.7 | Agree |

| If available in the future, the evaluation of disease activity by means of optical coherence tomography (OCT) variables should be performed periodically | 102 | 71.6 | Agree |

| Disability progression | |||

| Patients should be examined at each visit, and the EDSS should be verified | 104 | 98.1 | Strongly agree |

| Progression of disability should be considered in the evaluation of the treatment response | 104 | 98.1 | Strongly agree |

| An increase of at least one point on the EDSS is considered neurologically significant | 104 | 94.3 | Strongly agree |

| Evaluation of disability progression using the EDSS should be confirmed at 3 months | 104 | 77.9 | Agree |

| Evaluation of disability progression using the EDSS should be confirmed at 6 months | 103 | 93.2 | Agree |

| Evaluation of disability progression should be carried out using the EDSS and at least one other test, such as the timed 25-ft walk test, | 103 | 72.8 | Agree |

| Brain volume loss | |||

| Loss of brain volume should be included in the evaluation of treatment response | 104 | 71.2 | Agree |

| An evaluation or quantification of the loss of brain volume should be performed periodically | 104 | 67.3 | Agree |

| Neuropsychological aspects | |||

| In cognitive follow-up, the SDMT is a useful clinical tool for the evaluation of the treatment response | 104 | 72.2 | Agree |

| An evaluation of neuropsychological aspects should be carried out annually to assess treatment response | 104 | 67.3 | Agree |

| Applicability in clinical practice | |||

| The recommendations suggested throughout the questionnaire are applicable in standard clinical practice | 103 | 82.5 | Agree |

| In standard clinical practice, there are limitations to switching treatment | 103 | 72.8 | Agree |

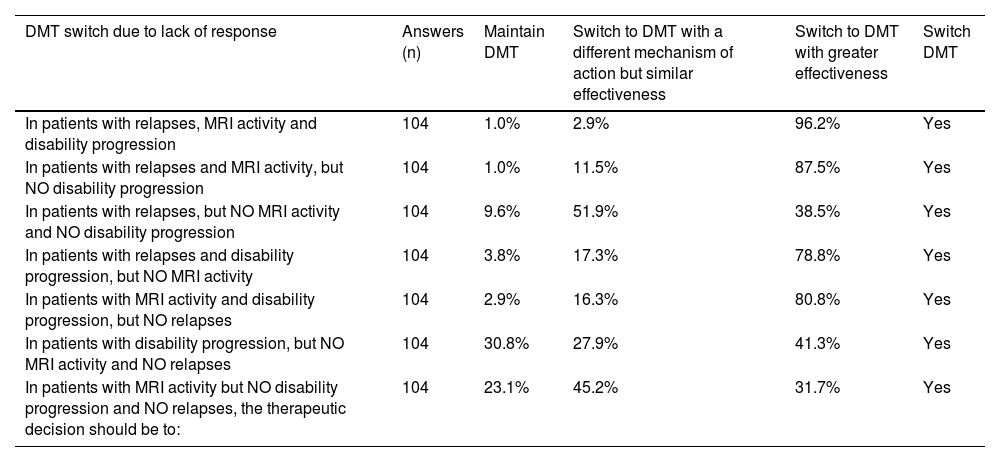

Survey results for statements on DMT switch due to lack of response.

| DMT switch due to lack of response | Answers (n) | Maintain DMT | Switch to DMT with a different mechanism of action but similar effectiveness | Switch to DMT with greater effectiveness | Switch DMT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In patients with relapses, MRI activity and disability progression | 104 | 1.0% | 2.9% | 96.2% | Yes |

| In patients with relapses and MRI activity, but NO disability progression | 104 | 1.0% | 11.5% | 87.5% | Yes |

| In patients with relapses, but NO MRI activity and NO disability progression | 104 | 9.6% | 51.9% | 38.5% | Yes |

| In patients with relapses and disability progression, but NO MRI activity | 104 | 3.8% | 17.3% | 78.8% | Yes |

| In patients with MRI activity and disability progression, but NO relapses | 104 | 2.9% | 16.3% | 80.8% | Yes |

| In patients with disability progression, but NO MRI activity and NO relapses | 104 | 30.8% | 27.9% | 41.3% | Yes |

| In patients with MRI activity but NO disability progression and NO relapses, the therapeutic decision should be to: | 104 | 23.1% | 45.2% | 31.7% | Yes |

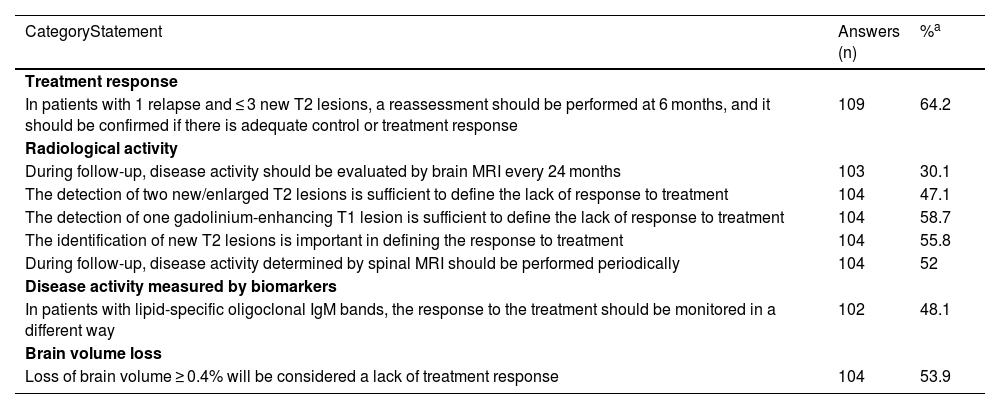

General agreement was obtained in 7 out of 9 questions, with 90.1% of neurologists indicating that patients should be evaluated 6 to 12 months from the start of treatment to determine treatment response. Additionally, 84.4% indicated that in patients without relapses and ≥ 3 new T2 lesions, a reassessment should be performed at 6 months and a confirmation of the presence of adequate control or treatment response should be confirmed. However, there was no agreement on the need to re-assess patients with 1 relapse and ≤ 3 new T2 lesions to confirm treatment response (64.2% agreed vs. 35.8% disagreed), or even in patients with 1 relapse and ≥ 3 new T2 lesions (66% disagreed vs. 33.9% agreed). Regarding the variables for assessing treatment response, there was agreement to evaluate MRI, relapses and progression of disability (95.4%), together with quality of life (QoL) (83.4%); cognitive status (87.1%); and brain volume loss (BVL) (71.3%). In addition, 99.1% of the neurologists indicated the need to determine treatment adherence prior to the evaluation of treatment response.

RelapsesGeneral agreement was achieved for all six statements, ranging from 81.1% to 98.1%. It was agreed that the relapses themselves are enough to define treatment response. Relapse evaluation should include the number from the start/switch of treatment, severity (intensity and/or sequelae), type (location and/or associated symptoms), and time of occurrence regarding the start/switch of treatment. However, it was also agreed (93.3%) that it is possible to define a lack of treatment response in the absence of relapses

Radiological activityGeneral agreement and disagreement were achieved in 8 and 2 statements (out of 15), respectively. It was agreed that MS activity should be systematically evaluated by MRI (94.3%), with and without contrast (87.8%). The reference MRI to assess treatment response should be performed at 3–6 months from the start of treatment (85.9%). At diagnóstico, disease activity should also be evaluated by spinal cord MRI (93.4%) and with follow-up brain MRI every 12 months (84.3%). It was also agreed (71.8%) that the detection of subclinical disease activity by MRI alone is sufficient to define lack of response to treatment. Detection of one new/enlarged hyperintense T2 lesion is not sufficient to define lack of response (80.8%). However, the detection of three or more new/enlarged T2 lesions or the detection of two or more gadolinium (Gd)-enhancing T1 lesions were considered to define lack of response, with 91.4% and 83.6% of agreement, respectively.

No general agreement/disagreement was reached with regards to the importance of the location of new/enlarged T2 lesions to define the response to treatment, nor to perform periodic spinal cord MRI in the follow-up for disease activity assessment.

Disease activity measured by biomarkersIf available in the future, it was agreed that an evaluation of MS activity through the determination of serum neurofilaments, chitinase 3-like-protein-1 and optical coherence tomography (OCT) variables should be performed periodically (83.3%, 66.7% and 71.6%, respectively); no general agreement/disagreement was reached regarding a change to treatment evaluation in MS patients with lipid-specific oligoclonal IgM bands.

Progression of disabilityGeneral agreement was achieved for all six questions in this section, ranging from 72.8% to 98.1%. Disability progression should be used to evaluate treatment response by examining the patient at each visit using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). An increase of at least one point on the EDSS score is considered neurologically significant (94.3% agreed), and this test should be used to confirm disability progression at both 3 and 6 months (77.9% and 93.2% of agreement, respectively). Moreover, 72.8% of the participants agreed to use the EDSS and at least one other test, such as the timed 25-ft walk (T25FW) test, to evaluate disability progression.

Brain volume lossIt was agreed that BVL should be included in the evaluation of treatment response (71.2% agreed), and that it should be conducted periodically (67.3% agreed). However, no agreement was reached to consider a BVL ≥ 0.4% as a sign of no response to treatment.

Neuropsychological aspectsThe Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) was considered a useful clinical tool for evaluating treatment response (72.2%). There was also general agreement for the annual evaluation of neuropsychological aspects for assessing treatment response (67.3%).

Switching the disease-modifying treatment due to lack of responseIn patients with MS relapses, disability progression or MRI activity, there was agreement (96.2%) to switch to another DMT with greater effectiveness upon lack of response. In patients with both MS relapses and MRI activity but no disability progression, there should also be a switch to a treatment with greater effectiveness (87.5% agreed). Similarly, in patients with both MRI activity and disability progression, but no MS relapses, a treatment with greater effectiveness should be administered (80.8%).

In patients with relapses but no MRI activity and no disability progression, there was no agreement, but the common recommendation (51.9%) was to switch to a treatment with a different mechanism of action but similar effectiveness.

Applicability in clinical practiceThe suggested recommendations could be implemented in clinical practice according to 82.5% of the participants, but 72.8% recognised that there are limitations to modifying treatment in MS patients in real-life practice.

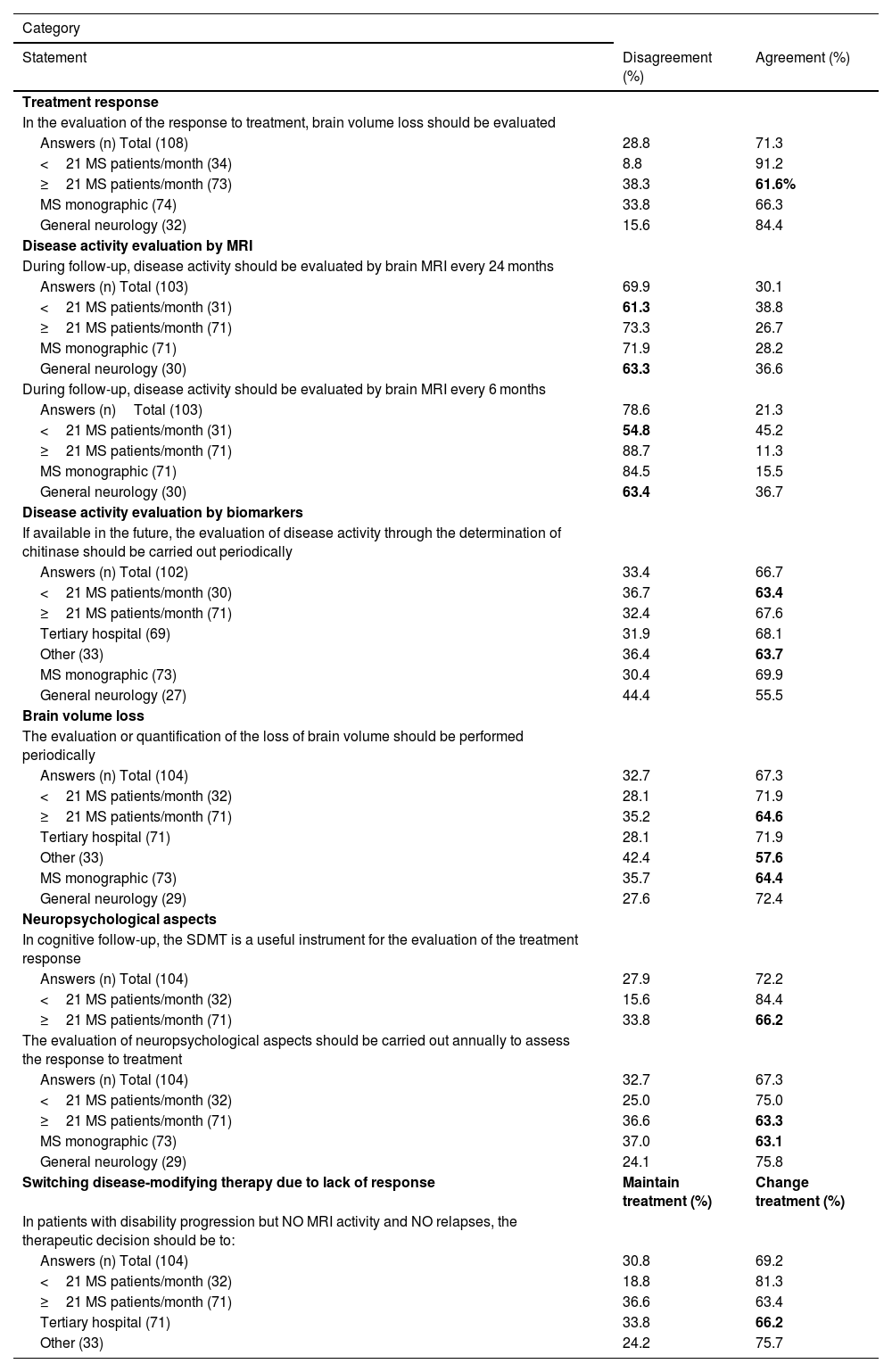

Subgroup analysisFor most of the statements, the results from the subgroup analysis matched those from the global results; however, general agreement or disagreement was not found for eight statements from six categories (Table 3).

Loss of agreement or disagreement after subgroup analysis.

| Category | ||

|---|---|---|

| Statement | Disagreement (%) | Agreement (%) |

| Treatment response | ||

| In the evaluation of the response to treatment, brain volume loss should be evaluated | ||

| Answers (n) Total (108) | 28.8 | 71.3 |

| <21 MS patients/month (34) | 8.8 | 91.2 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (73) | 38.3 | 61.6% |

| MS monographic (74) | 33.8 | 66.3 |

| General neurology (32) | 15.6 | 84.4 |

| Disease activity evaluation by MRI | ||

| During follow-up, disease activity should be evaluated by brain MRI every 24 months | ||

| Answers (n) Total (103) | 69.9 | 30.1 |

| <21 MS patients/month (31) | 61.3 | 38.8 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (71) | 73.3 | 26.7 |

| MS monographic (71) | 71.9 | 28.2 |

| General neurology (30) | 63.3 | 36.6 |

| During follow-up, disease activity should be evaluated by brain MRI every 6 months | ||

| Answers (n)Total (103) | 78.6 | 21.3 |

| <21 MS patients/month (31) | 54.8 | 45.2 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (71) | 88.7 | 11.3 |

| MS monographic (71) | 84.5 | 15.5 |

| General neurology (30) | 63.4 | 36.7 |

| Disease activity evaluation by biomarkers | ||

| If available in the future, the evaluation of disease activity through the determination of chitinase should be carried out periodically | ||

| Answers (n) Total (102) | 33.4 | 66.7 |

| <21 MS patients/month (30) | 36.7 | 63.4 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (71) | 32.4 | 67.6 |

| Tertiary hospital (69) | 31.9 | 68.1 |

| Other (33) | 36.4 | 63.7 |

| MS monographic (73) | 30.4 | 69.9 |

| General neurology (27) | 44.4 | 55.5 |

| Brain volume loss | ||

| The evaluation or quantification of the loss of brain volume should be performed periodically | ||

| Answers (n) Total (104) | 32.7 | 67.3 |

| <21 MS patients/month (32) | 28.1 | 71.9 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (71) | 35.2 | 64.6 |

| Tertiary hospital (71) | 28.1 | 71.9 |

| Other (33) | 42.4 | 57.6 |

| MS monographic (73) | 35.7 | 64.4 |

| General neurology (29) | 27.6 | 72.4 |

| Neuropsychological aspects | ||

| In cognitive follow-up, the SDMT is a useful instrument for the evaluation of the treatment response | ||

| Answers (n) Total (104) | 27.9 | 72.2 |

| <21 MS patients/month (32) | 15.6 | 84.4 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (71) | 33.8 | 66.2 |

| The evaluation of neuropsychological aspects should be carried out annually to assess the response to treatment | ||

| Answers (n) Total (104) | 32.7 | 67.3 |

| <21 MS patients/month (32) | 25.0 | 75.0 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (71) | 36.6 | 63.3 |

| MS monographic (73) | 37.0 | 63.1 |

| General neurology (29) | 24.1 | 75.8 |

| Switching disease-modifying therapy due to lack of response | Maintain treatment (%) | Change treatment (%) |

| In patients with disability progression but NO MRI activity and NO relapses, the therapeutic decision should be to: | ||

| Answers (n) Total (104) | 30.8 | 69.2 |

| <21 MS patients/month (32) | 18.8 | 81.3 |

| ≥21 MS patients/month (71) | 36.6 | 63.4 |

| Tertiary hospital (71) | 33.8 | 66.2 |

| Other (33) | 24.2 | 75.7 |

Note The results (%) of the subgroup that lost agreement or disagreement after subgroup analysis have been marked in bold.

The present study aimed to provide general consensus among MS neurologists on the monitoring of response to DMT as a way of optimising MS management. Establishing which assessments should be conducted to determine suboptimal treatment response is essential when reconsidering treatment modifications or switching between therapies. The therapeutic landscape for MS has significantly changed, with the approval of over ten new DMTs in the past decade alone; patients' clinical courses vary greatly; and patients do not all respond homogeneously to the same DMT. For these reasons, early identification of treatment failure is increasingly important, as it will make it possible to personalise treatment and to switch to a more beneficial DMT for each patient, ultimately improving the management of MS.

The results we obtained are highly representative of clinical practice throughout Spain, as MS neurologists from almost all regions of Spain participated in the study. MS neurologists agreed that MS patients should be evaluated 6–12 months after starting DMT to determine their therapeutic response. This frequency was previously recommended for the monitoring of clinical10 and radiological2 response after the start of DMT. MS neurologists also agreed that treatment response should be based on the evaluation of MRI scans, relapses and the progression of disability progression. Combining MRI and clinical activity has proven useful in previous approaches for identifying patients with suboptimal response.3,6–9,11,12 In patients treated with INFβ, MRI activity combined with relapses and/or increase of disability during the first year of treatment made it possible to detect patients at high risk of clinical activity and disease progression the next two years, while MRI or clinical activity alone did not (Rio score).8 A subsequent modification of the Rio score, which excluded the EDSS,7 accurately predicted treatment response,13 though the Rio score appeared slightly higher in high-risk patients.13 The assessment of the combination of MRI and clinical activity has also been recommended by the European treatment guidelines, despite the specific clinical activity to be measured not being specified.14

Additional agreement was achieved on ≥3 new/enlarged T2 lesions and ≥ 2 Gd-enhancing T1 lesions, separately, being sufficient to define suboptimal response. The T2 lesion cut-offs to detect therapeutic response vary among studies.5,7,9 The number of new/enlarged T2 and Gd-enhancing lesions agreed upon here is in line with the recommendations of the Canadian MS Working Group10 and with studies showing that ≥3 new/enlarged T2,11,15 and ≥ 2 Gd-enhancing lesions15 predicted short11 and long-term15 disability in INFβ-treated patients. Agreement was reached to perform reference brain MRI and follow-up MRI 3–6 and 12 months after the start of DMT, respectively, similarly to the recommendations in the European14 and MAGNIMS16 guidelines. It has been argued that the 3–6 month range for the reference MRI should be adapted depending on the pharmacodynamics of the DMT received.17 No assessment was considered necessary for patients with 1 relapse and ≥ 3 new T2 lesions, as this group of patients is considered non-responders. Additionally, no general consensus was observed about the use of spinal cord MRI when assessing therapeutic response.

In terms of clinical activity, it was agreed that disease progression should be considered when evaluating treatment response and that the EDSS and at least one other test should be conducted. Even though the EDSS is the most accepted tool for disability assessment, other measures such as the T25FW or the 9HPT are extensively used in the clinical setting. This is supported by evidence demonstrating that the addition of the T25FW and the 9HPT to the EDSS increased the identification of disability progression compared to each test alone.18 Additionally, using pooled clinical trial data, it has been shown that even though the EDSS alone predicted progression better than the T25FW and 9HPT together, when the latter are combined with Low Contrast Letter Acuity (LCLA) and the SDMT, they are more sensitive than the EDSS.19 This could be explained by the additive information from LCLA and the SDMT that is not captured by the other measurements, as suggested by the lack of correlation between the SDMT and EDSS.19 Accordingly, the use of the SDMT was agreed here to be a useful clinical tool for cognitive assessment, which should be performed annually for the evaluation of treatment response. The SDMT is widely considered a valid and reliable tool to measure cognitive changes in MS.20,21 It measures information processing speed, which is the most affected cognitive domain in MS.22 Since remote performance of the SDMT has proven similar validity and reliability as in-person testing,23 this format might be convenient, especially when patient mobility is limited.

Although patient-reported outcomes (PROs) to assess QoL have been underused in clinical practice, their implementation is expected to grow in the next years, as more MS-specific and validated PROs evidence increases.24 If resources were to become available, it was agreed that the evaluation of MS activity through serum neurofilaments, chitinase 3-like-protein-1, and OCT parameters should be periodically performed. Additionally, there was consensus for measuring BVL when monitoring treatment response. Including BVL with the modified Rio score improved prediction of disability progression compared to disease activity alone.25 However, the ≥0.4% threshold¸ previously proposed to be pathological in MS patients,26,27 was not agreed here to be indicative of lack of treatment response. Though adding BVL to the evaluation of treatment response is warranted, its implementation in routine clinical practice is still not straightforward. The main reasons might be the current lack of standardisation of acquisition protocols, technical expertise and resources to perform the post-processing of the images, together with other MRI scans or confounding factors of MS that hinder their interpretation.28 Overall, these fluid and structural biomarkers will need to be validated and the technical limitations overcome before their incorporation into the clinical setting.

MS neurologists agreed to escalate to a more effective DMT rather than to a DMT with a different mechanism of action, when relapses, MRI activity and disability progression or at least two of these measurements are detected. When only one of these outcomes is present, up to 40% of the MS neurologists agreed to switch to a more effective DMT, showing low tolerance to the presence of disease activity. Switching to a more effective DMT is supported by studies showing better outcomes with this strategy.29 In fact, it has been argued that early high-efficacy therapy results in better clinical outcomes. Ongoing randomised clinical trials (TREAT-MS and DELIVER-MS) will provide further evidence on which strategy is more adequate to prevent disease progression. Importantly, neurologists agreed that there are limitations to switching treatment in routine clinical practice, probably due to the accessibility to treatments. Despite these limitations, neurologists should aim to accurately identify individual responsiveness to treatment in a timely manner. The detection of treatment failure will allow them to consider, in dialogue with the patient and, based on the patient characteristics and preferences, the most effective, safe and convenient treatment switch for each patient, attaining a more personalised therapeutic approach.

Lastly, the present study highlighted the lack of a generally accepted definition of suboptimal treatment response in MS. Future efforts should be made to clarify the definition of suboptimal and optimal response. Regardless of if no evidence of disease activity or minimal evidence of disease activity are the goals to strive for, the incorporation of new measurements such as PROs, imaging and fluid biomarkers seems likely to occur along with advances in digital technology and artificial intelligence.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, areas of agreement on the monitoring of DMT response were identified in all the categories. MS neurologists reached general agreement on which and when clinical and radiological measures should be performed and on changing the approach when a lack of response is detected. The results are expected to help neurologists to improve MS management. Future real-world studies will confirm whether this expectation is fulfilled.

Availability of data and materialNot applicable.

Author contributions*All authors have contributed equally.

Ethics approvalNot applicable.

Consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

FundingThis study was funded by Novartis Farmacéutica S.A. The sponsor did not have any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Patient consent (informed consent)The study did not include human subjects and, therefore, no informed consent was required.

Ethical considerationsThe study did not include human subjects and, therefore, this is not applicable.

The authors would like to thank Ernesto Estefanía (Pivotal, S.L.U.) and Laura Prieto del Val (Evidenze Clinical Research) for their support in the preparation of the manuscript. The authors are also thankful to all the collaborators in the project: Virginia Meca (Hospital La Princesa, Madrid), Sara Eichau (Hospital Virgen de la Macarena, Sevilla), Ester Moral (Hospital Broggi, Barcelona), Antonio García (Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid), Francisco Gascón (Hospital Clínico Valencia, Valencia), Maria Luisa Martínez (Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), Carmen Calles (Hospital Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca), Montserrat Gómez (Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres), Yolanda Aladro (Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Madrid), Eduardo Agüera (Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba), Luis Querol (Hospital Sant Pau, Barcelona), Agustín Oterino (Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander), José Meca (Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia), Ramón Ara (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza), Eduardo Durán (Complejo Hospitalario de Huelva, Huelva), Adrián Ares (Hospital de León, León), and Lucía Forero (Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, Cádiz).

Survey results for statements where general agreement or disagreement was not achieved.

| CategoryStatement | Answers (n) | %a |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment response | ||

| In patients with 1 relapse and ≤ 3 new T2 lesions, a reassessment should be performed at 6 months, and it should be confirmed if there is adequate control or treatment response | 109 | 64.2 |

| Radiological activity | ||

| During follow-up, disease activity should be evaluated by brain MRI every 24 months | 103 | 30.1 |

| The detection of two new/enlarged T2 lesions is sufficient to define the lack of response to treatment | 104 | 47.1 |

| The detection of one gadolinium-enhancing T1 lesion is sufficient to define the lack of response to treatment | 104 | 58.7 |

| The identification of new T2 lesions is important in defining the response to treatment | 104 | 55.8 |

| During follow-up, disease activity determined by spinal MRI should be performed periodically | 104 | 52 |

| Disease activity measured by biomarkers | ||

| In patients with lipid-specific oligoclonal IgM bands, the response to the treatment should be monitored in a different way | 102 | 48.1 |

| Brain volume loss | ||

| Loss of brain volume ≥ 0.4% will be considered a lack of treatment response | 104 | 53.9 |