Allergic enterocolitis, also known as food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), is an increasingly reported and potentially severe non-IgE mediated food allergy of the first years of life, which is often misdiagnosed due to its non-specific presenting symptoms and lack of diagnostic guidelines.

ObjectiveWe sought to determine the knowledge of clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic features of FPIES among Italian primary-care paediatricians.

MethodsA 16-question anonymous web-based survey was sent via email to randomly selected primary care paediatricians working in the north of Italy.

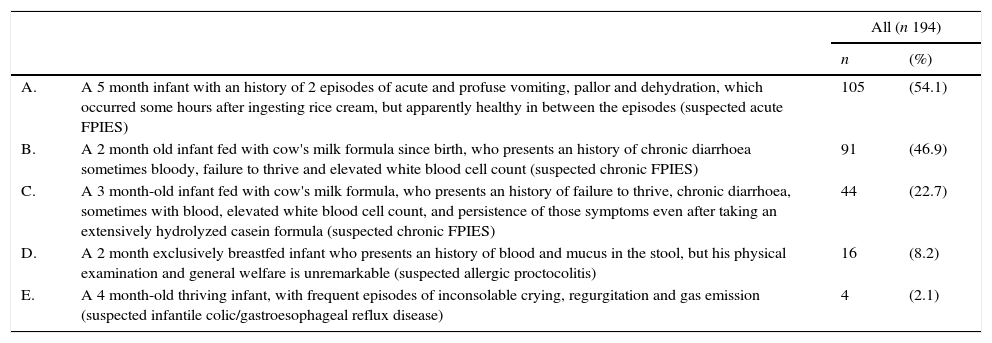

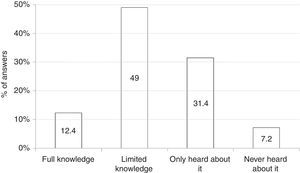

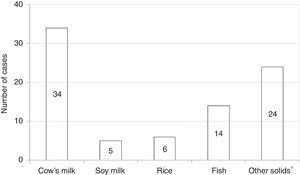

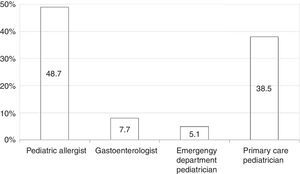

ResultsThere were 194 completed surveys (48.5% response rate). Among respondents, 12.4% declared full understanding of FPIES, 49% limited knowledge, 31.4% had simply heard about FPIES and 7.2% had never heard about it. When presented with clinical anecdotes, 54.1% recognised acute FPIES and 12.9% recognised all chronic FPIES, whereas 10.3% misdiagnosed FPIES as allergic proctocolitis or infantile colic. To diagnose FPIES 55.7% declared to need negative skin prick test or specific-IgE to the trigger food, whereas 56.7% considered necessary a confirmatory oral challenge. Epinephrine was considered the mainstay in treating acute FPIES by 25.8% of respondents. Only 59.8% referred out to an allergist for the long-term reintroduction of the culprit food. Overall, 20.1% reported to care children with FPIES in their practice, with cow's milk formula and fish being the most common triggers; the diagnosis was self-made by the participant in 38.5% of these cases and by an allergist in 48.7%.

ConclusionThere is a need for promoting awareness of FPIES to minimise delay in diagnosis and unnecessary diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Allergic enterocolitis, also referred to as food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), is a non-IgE-mediated food allergy which has been increasingly reported over the last decade.1–3 Although the prevalence of the disease is unknown, a recent population-based birth cohort study of over 13,000 infants reported a significant cumulative incidence of FPIES to cow's milk (CM) compared to IgE-mediated CM allergy.4

FPIES primarily affects children in the first year of life, with CM, soy, grains and fish being the most commonly reported offending foods.1–3 Nevertheless, several other solid foods, even unsuspected foods, have recently been reported as responsible of FPIES.5,6

A crucial issue with FPIES is that diagnosis is not always straightforward.7,8 FPIES presents with acute or chronic non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms which make the differential diagnosis a true challenge.8 There is evidence that affected children often experience several acute episodes before being correctly diagnosed, therefore undergoing extensive workups and unnecessary treatments.1–3 In some cases these interventions can be invasive, such as lumbar puncture or laparotomy for acute FPIES misdiagnosed as meningitis or surgical abdominal condition, respectively.3 The lack of specific laboratory diagnostic tests, the limited understanding of the immunopathogenesis as well as the low level of awareness among paediatricians and emergency department physicians further contribute to the risk of delayed identification of FPIES.9,10 Indeed, in a recent abstract reporting a survey conducted among 86 general American paediatricians only 12% declared a full understanding of FPIES, whereas 24% reported to have no knowledge of this disease.11

Currently there are no data about the level of understanding of FPIES among Italian medical providers. We sought to determine the knowledge of clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic features of FPIES among a group of primary care paediatricians working in the north of Italy by using a web-based survey questionnaire.

Materials and methodsThe questionnaire was developed as a pilot version in Italian language by a panel of experts, including two paediatric allergists, one paediatric allergist and gastroenterologist and two primary care paediatricians, based on their personal clinical experience and extensive review of the relevant literature on FPIES. The survey was pilot-tested and revised numerous times with primary care paediatricians to evaluate the survey for clarity and interoperator reliability.

The questionnaire consisted of 16 items distributed in five dimensions, including general awareness of FPIES, knowledge of clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic features of FPIES and personal experiences with affected children.

The questionnaire was converted in an Internet-based survey with Google Drive™ (Google Drive™, © 2012 Google Inc. all rights reserved), a free available computer platform which allows creation of web-based survey forms, real-time web-storage of collected data, real-time display of survey results and easy download of every participants’ recorded data in an Excel© format for statistical analysis.

Between February and September 2014, the survey was sent via email to 400 Italian primary care paediatricians. Participants were randomly selected among physicians registered with the Italian National Health System as primary care paediatricians working in the geographical areas around the cities of Verona and Turin. Selection of participants and email transmission were performed in a blinded manner by a medical doctor not involved in the study.

During this pilot phase of the survey, information on physician demographics and patients characteristics was never requested in order to protect their confidentiality. Only yes/no and multiple-choice questions were used. Participants were allowed to skip questions regarding their personal experience with patient diagnosed with FPIES. Survey completion time was approximately 10–15min. Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions of responses were used to analyse the collected data.

ResultsThe survey was completed by 194 primary care paediatricians (48.5% response rate). Of them, 123 (63%) were paediatricians working in the geographical area of the city of Verona.

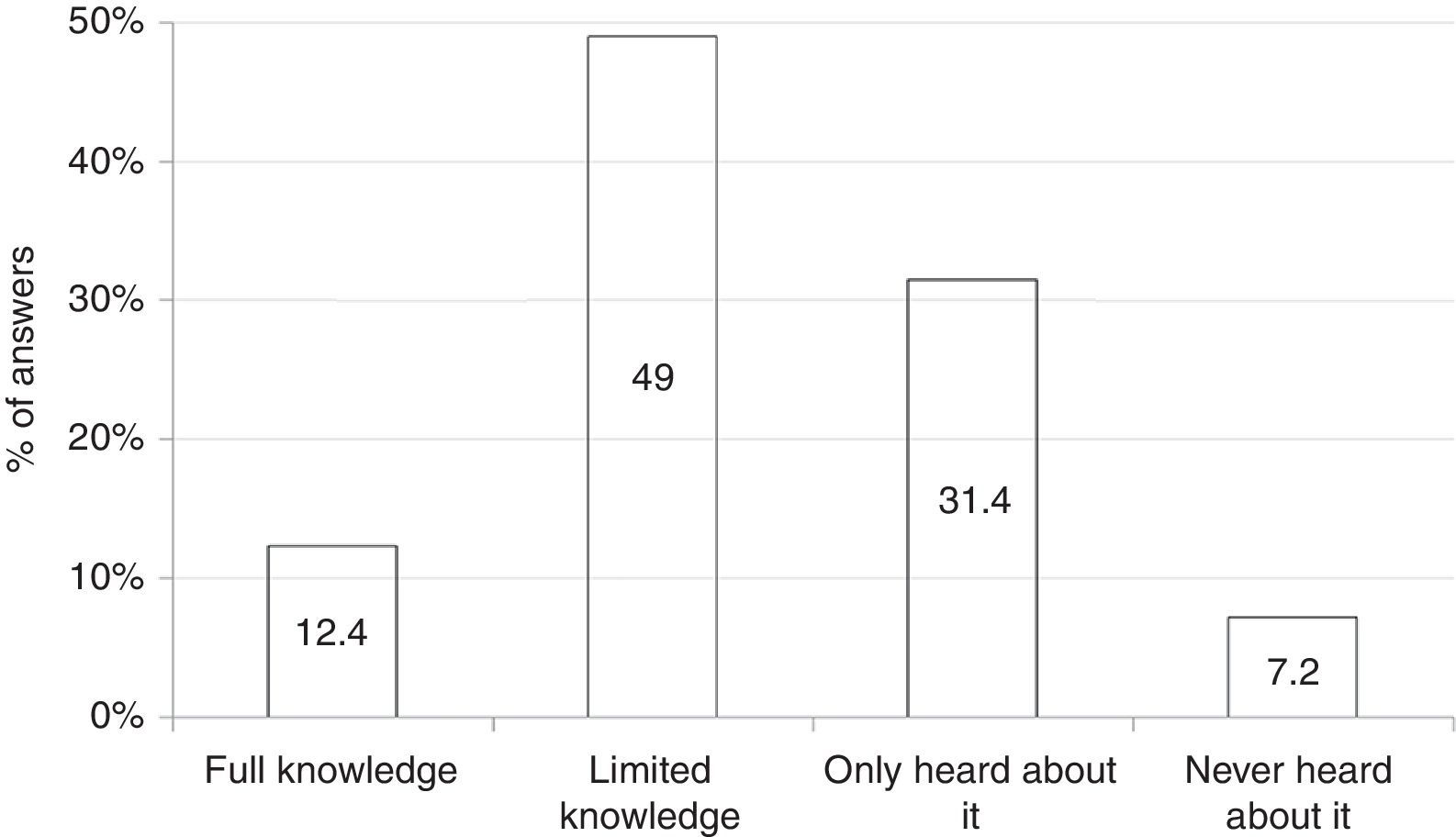

Among all 194 respondents, 24 (12.4%) declared full understanding of clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic features of FPIES; 95 (49%) limited knowledge of diagnostic and therapeutic features; 61 (31.4%) had simply heard about FPIES; and 14 (7.2%) had never heard about this disease (Fig. 1).

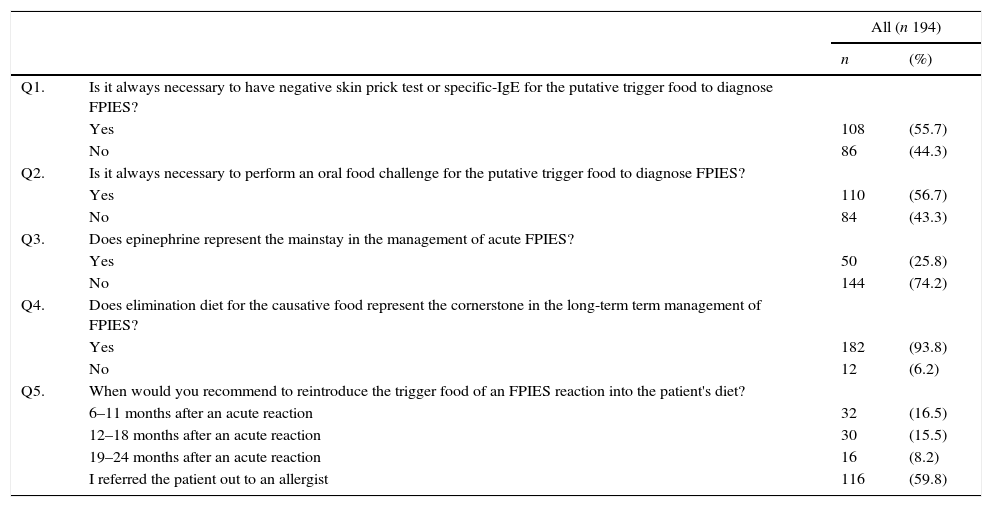

When presented with clinical anecdotes, including one suspected case of acute solid-food FPIES and two suspected cases of chronic FPIES, 54.1% of respondents recognised acute FPIES, 12.9% recognised both cases of chronic FPIES, 46.9% recognised only the first case of chronic FPIES and 22.7% recognised only the second one. In addition, 8.2% of participants misdiagnosed FPIES as allergic proctocolitis, whereas 2.1% confounded FPIES with a case which could be suspected for infantile colic or gastroesophageal reflux disease (Table 1). In the subgroup declaring full understanding of the disease, 25% recognised two of three cases of suspected FPIES, whereas no one recognised them all. Only 8/194 (4.1%) respondents belonging to the subgroups declaring limited knowledge of the disease recognised all the suspected cases of FPIES (data not shown).

Clinical vignettes of suspected cases of FPIES. Multiple answers were allowed.

| All (n 194) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | ||

| A. | A 5 month infant with an history of 2 episodes of acute and profuse vomiting, pallor and dehydration, which occurred some hours after ingesting rice cream, but apparently healthy in between the episodes (suspected acute FPIES) | 105 | (54.1) |

| B. | A 2 month old infant fed with cow's milk formula since birth, who presents an history of chronic diarrhoea sometimes bloody, failure to thrive and elevated white blood cell count (suspected chronic FPIES) | 91 | (46.9) |

| C. | A 3 month-old infant fed with cow's milk formula, who presents an history of failure to thrive, chronic diarrhoea, sometimes with blood, elevated white blood cell count, and persistence of those symptoms even after taking an extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (suspected chronic FPIES) | 44 | (22.7) |

| D. | A 2 month exclusively breastfed infant who presents an history of blood and mucus in the stool, but his physical examination and general welfare is unremarkable (suspected allergic proctocolitis) | 16 | (8.2) |

| E. | A 4 month-old thriving infant, with frequent episodes of inconsolable crying, regurgitation and gas emission (suspected infantile colic/gastroesophageal reflux disease) | 4 | (2.1) |

12.9% (25/194) of respondents recognised both chronic FPIES.

When dealing with diagnostic procedures, 55.7% of respondents declared to need negative result in skin prick test (SPT) or allergen-specific IgE antibody to the trigger food to make the diagnosis of FPIES. In addition, 56.7% considered necessary a confirmatory oral food challenge (OFC) for a definitive diagnosis (Table 2).

Survey respondents’ opinion on diagnostic and therapeutic features of FPIES.

| All (n 194) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | ||

| Q1. | Is it always necessary to have negative skin prick test or specific-IgE for the putative trigger food to diagnose FPIES? | ||

| Yes | 108 | (55.7) | |

| No | 86 | (44.3) | |

| Q2. | Is it always necessary to perform an oral food challenge for the putative trigger food to diagnose FPIES? | ||

| Yes | 110 | (56.7) | |

| No | 84 | (43.3) | |

| Q3. | Does epinephrine represent the mainstay in the management of acute FPIES? | ||

| Yes | 50 | (25.8) | |

| No | 144 | (74.2) | |

| Q4. | Does elimination diet for the causative food represent the cornerstone in the long-term term management of FPIES? | ||

| Yes | 182 | (93.8) | |

| No | 12 | (6.2) | |

| Q5. | When would you recommend to reintroduce the trigger food of an FPIES reaction into the patient's diet? | ||

| 6–11 months after an acute reaction | 32 | (16.5) | |

| 12–18 months after an acute reaction | 30 | (15.5) | |

| 19–24 months after an acute reaction | 16 | (8.2) | |

| I referred the patient out to an allergist | 116 | (59.8) | |

With regard to management of the disease, 25.8% of respondents considered epinephrine as the mainstay in the treatment of acute FPIES (Table 2). Most participants (93.8%) considered the elimination diet for the causative food as the cornerstone in the long-term management of FPIES. In addition, 59.8% of respondents would refer out to an allergist specialist for the reintroduction of the culprit food into the child's diet.

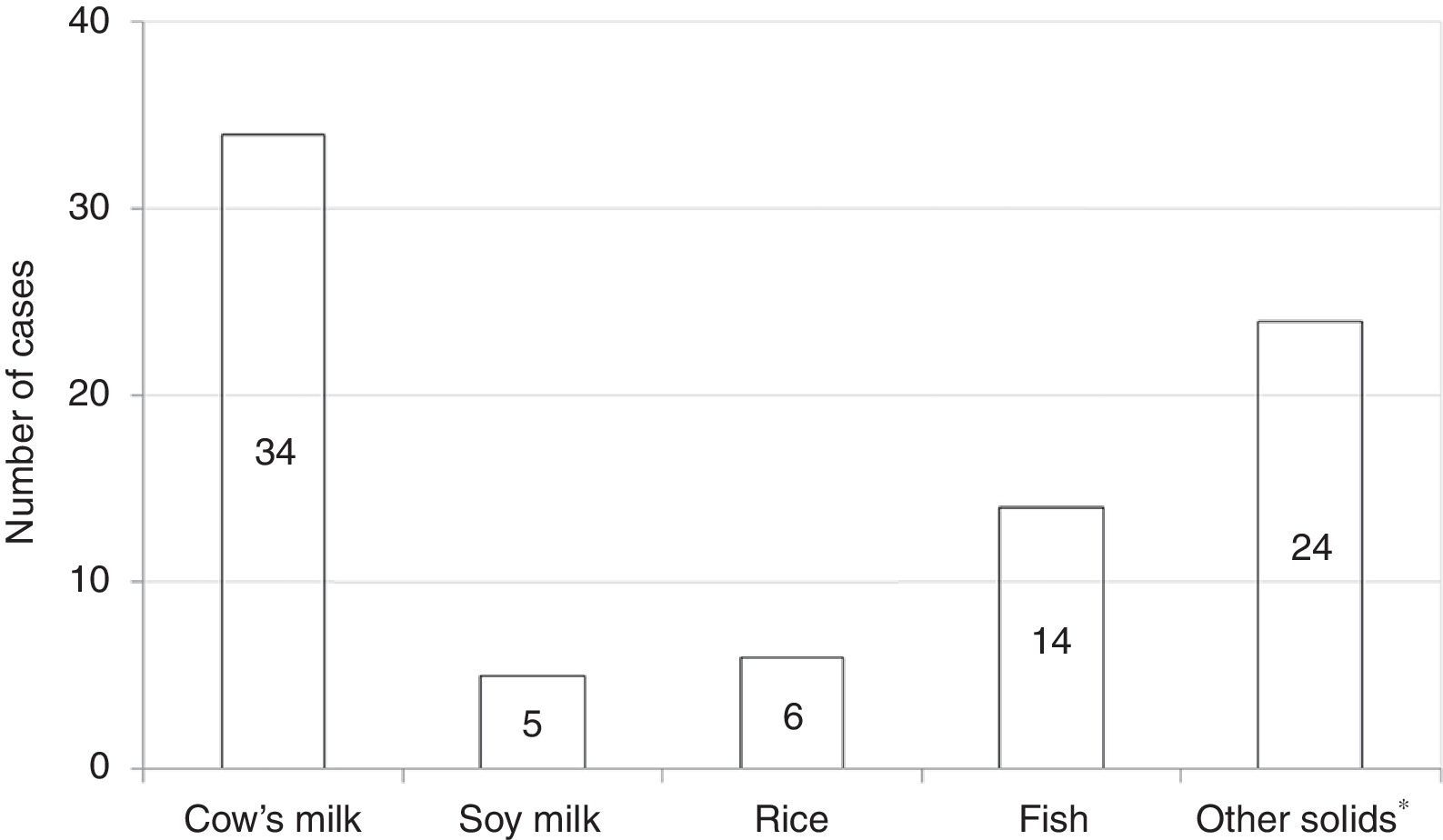

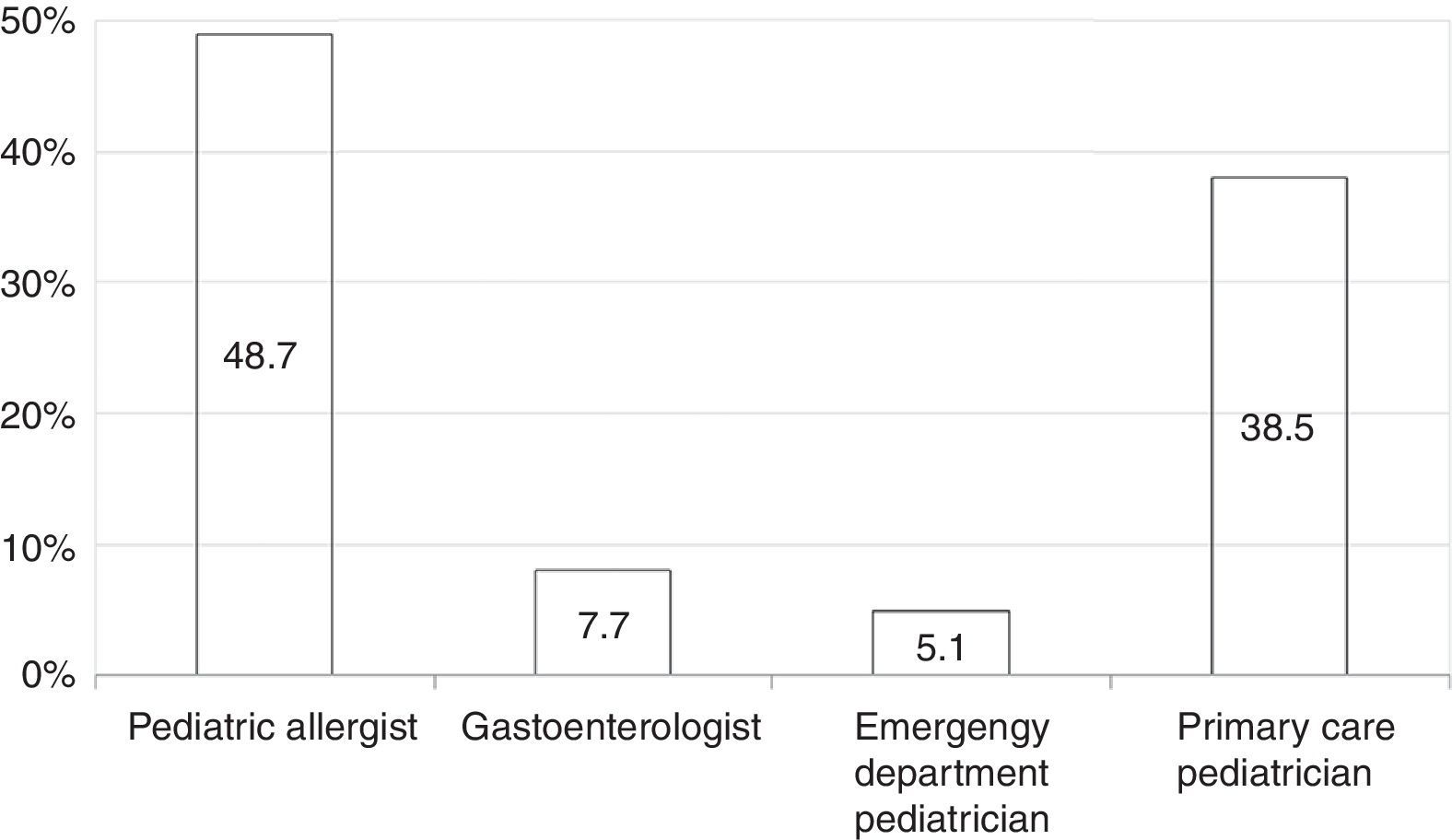

Among all participants, 39 (20.1%) reported to care patients with FPIES in their clinical practice (data not shown). In this cohort of affected children the most commonly reported causative food was CM formula followed by solid foods (Fig. 2). Fish was the most frequently reported trigger among solids (Fig. 2). The diagnosis of FPIES was established by a paediatric allergist in 48.7% of cases, a gastroenterologist in 7.7%, an emergency department paediatrician in 5.1%, and by the primary-care paediatrician himself in 38.5% of cases (Fig. 3). Among this latter subgroup of paediatricians who self-made the diagnosis of FPIES, 40% declared full understanding of the disease, 60% declared to need negative SPT or specific-IgE for the putative culprit food to diagnose FPIES and 26.7% considered epinephrine as the mainstay in the treatment of acute FPIES (data not shown).

Over the last decade the number of reported cases of FPIES has progressively increased.12,13 FPIES can present either in acute or chronic forms. Acute FPIES commonly manifests with episodes of repetitive and even profuse vomiting, sometimes with diarrhoea, which occur 1–4h after ingestion of the culprit food. These symptoms may progress to dehydration, pallor, hyporeactivity and even shock in about 15% of cases. Chronic symptoms are usually elicited by regular intake of the trigger food and tend to be more subtle, including intermittent vomiting, diarrhoea or bloody diarrhoea, abdominal distension, weight loss and failure to thrive.9

One main challenge often faced by children with FPIES is the delay in the correct diagnosis, which compromises patient's and family's quality of life due to the risk of unnecessary investigations and even more dramatic lack of proper management.14 Poorly-defined prevalence of the disease and low level of understanding in the medical community certainly contribute to the difficulty in diagnosis and management of FPIES. In this scenario, primary care paediatricians may play a crucial role because they provide comprehensive care for infants and represent the first referral for children's health.

In a recent abstract, Menon et al. reported a survey study conducted among 86 general paediatricians registered with the American Medical Association, showing that 80% of respondents had limited or no knowledge of FPIES.11 Herein we report the results of the first observational, multicentre web-based survey on the awareness of FPIES conducted among Italian primary care paediatricians. Similarly to the data reported in the abstract by Menon et al.11, approximately 90% of our respondents declared to have little or no knowledge of FPIES, with half of them recognising acute FPIES. On the contrary, our respondents showed a higher difficulty in identifying chronic forms, with only 12.9% recognising both suspected cases of chronic FPIES. Interestingly, in the subgroup of respondents declaring full understanding of the disease, only 25% recognised two of three suspected cases of FPIES, whereas no one recognised them all. Children with chronic FPIES are often referred to the primary care paediatrician, who faces an insidious challenge due to lack of definition of the disease and even more difficult differential diagnosis than acute FPIES, which include metabolic disorders and primary immunodeficiencies.7,8

With regard to FPIES causing-foods, fish was the most commonly reported solid culprit food in the cohort of children with FPIES cared by our respondents. This finding is consistent with recent reports from Italy and Spain, which mention fish as a relevant trigger of solid FPIES.2,15

When considering diagnostic features, a few more than half of respondents agreed that negative SPT or specific-IgE to the trigger food and confirmatory OFC are needed to diagnose FPIES. Noteworthy, among the subgroup of respondents who self-diagnosed children with FPIES, only less than half declared to have full knowledge of the disease. Up to 90% of children with FPIES typically show negative SPT or specific IgE to the causative food.1 However, there is increasing evidence that positive SPT or specific IgE to the FPIES inducing-food can be detected either at presentation or during follow-up, with one recent study showing specific IgE-sensitisation in 24% of subjects.12 These cases are referred as “atypical” FPIES, which are often characterised by a more prolonged course of the disease and risk of progression to typical IgE-mediated immediate hypersensitivity reactions.4,12 Thus, negative SPT or allergen-specific IgE to the FPIES causing-food are suggestive but not necessary to diagnose the disease.

The lack of specific diagnostic biomarkers makes OFC the reference standard test to diagnose FPIES.16 Nevertheless, in line with statements proposed by previous authors16,17, we agree that a confirmatory OFC may not be needed for initial diagnosis of FPIES in cases of two or more acute episodes triggered by the same food in a six-month period, with prompt resolution of symptoms after avoidance of the causative food.

When evaluating management of the disease, adrenalin was considered the mainstay in the treatment of acute FPIES by nearly 30% of all respondents. A similar result has also emerged in the subgroup of paediatricians who self-made the diagnosis of FPIES. Children with acute FPIES represent one of the causes of access to the emergency department for repetitive vomiting. Parallel to removal of the offending food, the cornerstone in the treatment of acute FPIES is fluid replacement. Oral rehydration can be sufficient for mild cases if tolerated, whereas intravenous hydration should be used for moderate to severe cases associated with intravenous steroids. The role of epinephrine is still debated and its use is indicated in cases of hypotension non responding to intravenous fluids and steroids.18 Recently, the use of the antiemetic ondansetron has been proposed for acute symptoms with promising outcomes.19,20 Regarding long term-management of the disease, the majority of respondents correctly agreed to recommend the elimination diet for the culprit food. However, only 59.8% would refer out to an allergist for the reintroduction of the trigger food to the patients’ diet.

Currently there are no specific recommendations regarding the most appropriate timing for reintroduction of the culprit food to the diet. In most cases FPIES resolves by five years of age, with CM FPIES showing a high resolution rate by three years of age in different reports.2,4,21 However data on age of FPIES resolution are scarce, especially for solid foods, and seem to vary in different countries, with one recent US study reporting a low rate of CM FPIES resolution (20%) by three years of age.12 In a recent study the atopy patch test were tested to predict tolerance development in FPIES showing poor utility.22 An OFC is mandatory to test the development of tolerance to the culprit food and it should be performed in hospital supervised settings, because of the possible occurrence of acute severe symptoms. To this purpose, we agree with previous authors in recommending follow-up OFC every 12–18 months after the last acute FPIES reaction.18

The limitations of our study are related to the pilot phase of the survey and include the use of a non-standardised questionnaire and the inability to correlate the level of understanding of FPIES to the years of clinical practice of respondents. However, this was a pilot survey and we evaluated several times, with primary care paediatricians, the issues of the study related to clarity and reliability. To the best of our knowledge, standardised, validated surveys on this matter are not available.

Another possible limitation is the relatively low response rate, which could have been influenced by the fact that the survey required basic knowledge of a computer and Internet. The response rate was 48% which is modest and has the potential for bias. Even though it is similar to that of another published national survey of paediatricians,23 it is more likely that paediatricians who felt more interested about allergies were more likely to respond. Nevertheless, this could lead to consider the actual practice even worse than the results of the study.

A subsequent observational, multicentre, prospective study involving a larger sample of participants with a test-retest analysis will be needed to validate this questionnaire and to confirm the present results.

Nevertheless, by using an innovative survey form we have added confirmatory evidence that there is a need for promoting education and awareness of FPIES among primary care doctors and medical providers who may care for these children to avoid the potentially harmful consequences of an incorrect diagnosis and management of this disease. As in other countries, it is also advisable that an association of families for FPIES can help the dissemination programs of this disease (http://fpiesfoundation.org).

Ethical disclosuresConfidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We are grateful to Dr. Giampiero Chiamenti for the random selection of participants and distribution of the survey.