Atopic dermatitis is common among children of 0–5 years old. Treatment consists of emollients and topical corticosteroids. Due to corticophobia, however, adherence to topical corticosteroids is low. Our aim was to find factors that influence opinions about topical corticosteroids among parents of children with atopic dermatitis.

MethodsA qualitative focus group study in secondary care with parents of children with atopic dermatitis. Questions concerned opinions, attitude, sources of information, and the use of topical corticosteroids.

ResultsThe parents indicated that they lack knowledge about the working mechanism and side effects of topical corticosteroids. Dermatologists and paediatricians emphasise the beneficial effects, whereas other healthcare workers and lay people often express a negative attitude.

ConclusionsThis study gives a complete overview of factors influencing adherence. Treatment with topical corticosteroids can be improved by better informing parents about the working mechanisms, the use, and how to reduce the dose. Healthcare professionals need to be aware of the consequences of their negative attitude concerning topical corticosteroids.

Atopic dermatitis is a common inflammatory skin disease that affects 15–20% of children worldwide.1 Atopic dermatitis is characterised by itching and scratching that causes damage to the skin.2 There is evidence of a negative relationship between quality of life and the intensity of itch among children.3 The treatment of atopic dermatitis consists of a combination of emollients and topical corticosteroids.4 The use of topical corticosteroids reduces the symptoms and improves quality of life.5 The appropriate use of topical corticosteroids is safe, and side effects rarely occur.5 However, up to 80% of child patients with atopic dermatitis and their parents state that they experience fear regarding topical corticosteroids and are reluctant to use them.6–11

The term ‘corticophobia’ describes exaggerated concerns and fears regarding corticosteroid use.6 Corticophobia leads to low adherence among users of topical corticosteroids. Only about 30% of patients with atopic dermatitis follow the medical instructions.9 Consequently, this low adherence leads to insufficient treatment and the persistence of symptoms.

By the use of focus groups with parents, further insights are obtained from their opinions regarding topical corticosteroids. These insights into parental needs are helpful for caregivers in their care for these patients.

The aim of this study is to determine all the factors that influence opinions about topical corticosteroids among parents of children with atopic dermatitis.

MethodsParticipants and recruitmentParticipants were parents of young children with atopic dermatitis. The participants were located using medical records from the Medical Centre Leeuwarden, an 800-bed teaching hospital in the north of the Netherlands. The participants were contacted by telephone and excluded if they did not speak Dutch fluently. The participants did not receive compensation.

Focus groupsFor this study, we conducted focus group sessions. Prior to each session, the participants completed a short questionnaire to record their demographic information. In order not to influence the opinions of the participants, the exact purpose of the study was not discussed beforehand. Only after the focus group had ended did we explicitly ask for specific factors that would provide better adherence.

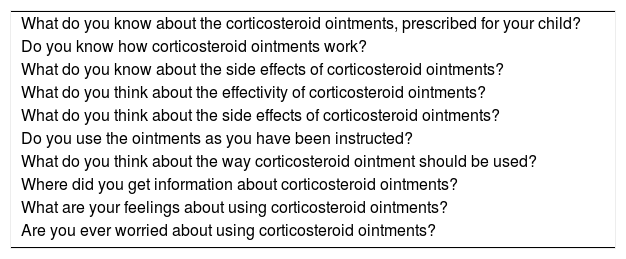

We used a semi-structured guide with open questions (Table 1). The questions were divided into four subjects: parents’ opinion; knowledge; sources of information; and the use of topical corticosteroids.

Ten questions used to start the discussions in the focus group sessions.

| What do you know about the corticosteroid ointments, prescribed for your child? |

| Do you know how corticosteroid ointments work? |

| What do you know about the side effects of corticosteroid ointments? |

| What do you think about the effectivity of corticosteroid ointments? |

| What do you think about the side effects of corticosteroid ointments? |

| Do you use the ointments as you have been instructed? |

| What do you think about the way corticosteroid ointment should be used? |

| Where did you get information about corticosteroid ointments? |

| What are your feelings about using corticosteroid ointments? |

| Are you ever worried about using corticosteroid ointments? |

The focus groups were audio-recorded. These recordings were transcribed verbatim and coded using the qualitative analysis programme Atlas.ti (version 1.0.51).

AnalysisAfter the pilot, codes were agreed upon with the consensus of all the researchers. Each focus group session was analysed independently by two researchers. Discrepancies in codes were discussed and, following a consensus, a third researcher reviewed the encoding. After all focus groups had been encoded, we refined the final set of codes, and the subcategories were themed. For clarity, two researchers summarised the content by studying all the quotes per code. A third researcher verified whether this summary was representative.

The local medical ethical committee authorised this study. The parents provided written consent to join the focus groups. Care was taken to protect privacy and confidentiality.

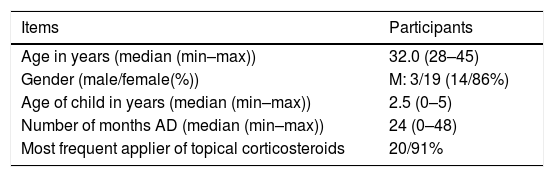

ResultsThere were 22 participants, their age ranged from 28 to 45 years old and most were female (19, or 84%). Almost all (20, or 91%) were the people who applied the ointments the most often (see Table 2).

Demographic information of focus group participants.

| Items | Participants |

|---|---|

| Age in years (median (min–max)) | 32.0 (28–45) |

| Gender (male/female(%)) | M: 3/19 (14/86%) |

| Age of child in years (median (min–max)) | 2.5 (0–5) |

| Number of months AD (median (min–max)) | 24 (0–48) |

| Most frequent applier of topical corticosteroids | 20/91% |

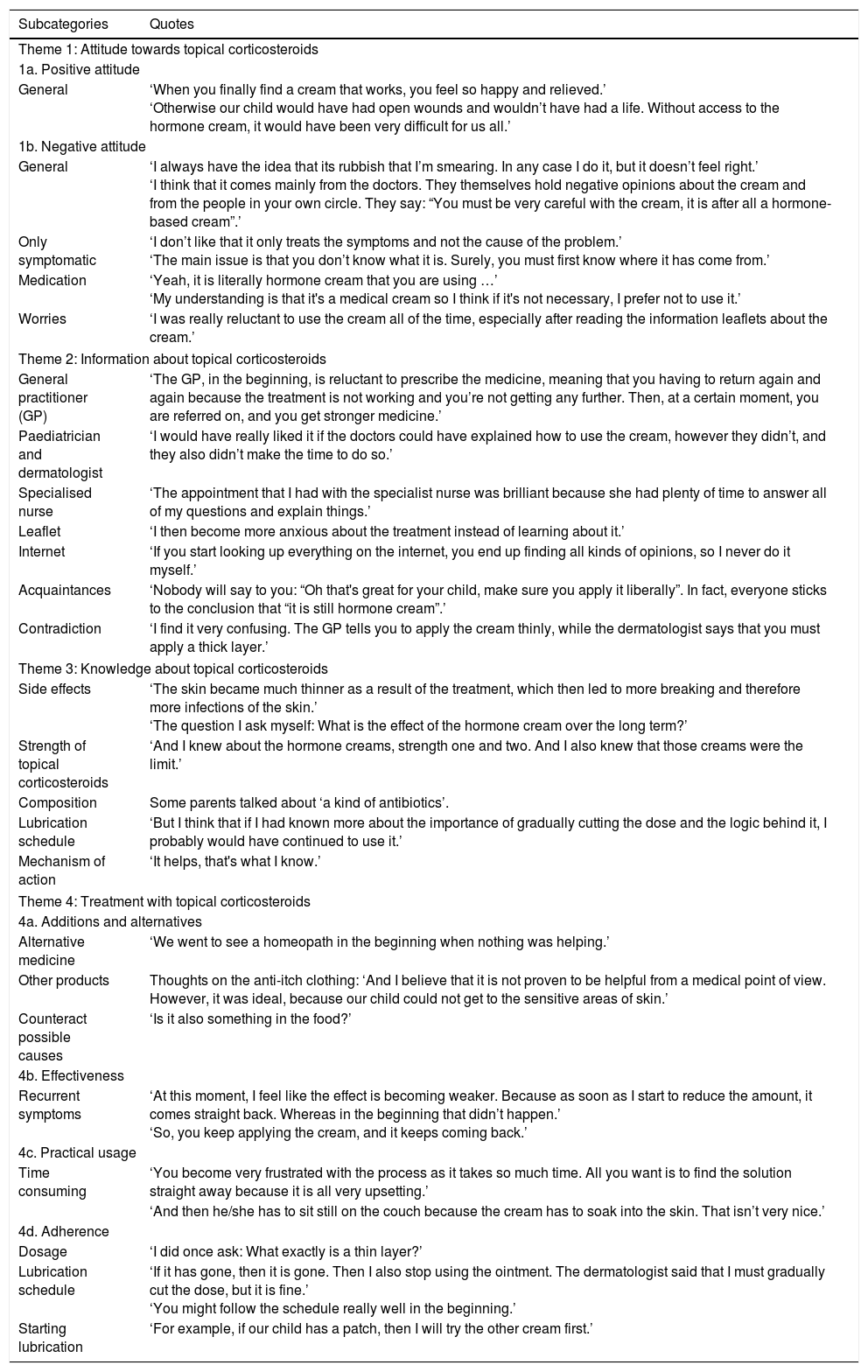

Three main themes were extracted, and these were divided into sub-themes. The quotes are presented by theme in Table 3.

Categorised quotes from the focus group sessions.

| Subcategories | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Attitude towards topical corticosteroids | |

| 1a. Positive attitude | |

| General | ‘When you finally find a cream that works, you feel so happy and relieved.’ ‘Otherwise our child would have had open wounds and wouldn’t have had a life. Without access to the hormone cream, it would have been very difficult for us all.’ |

| 1b. Negative attitude | |

| General | ‘I always have the idea that its rubbish that I’m smearing. In any case I do it, but it doesn’t feel right.’ ‘I think that it comes mainly from the doctors. They themselves hold negative opinions about the cream and from the people in your own circle. They say: “You must be very careful with the cream, it is after all a hormone-based cream”.’ |

| Only symptomatic | ‘I don’t like that it only treats the symptoms and not the cause of the problem.’ ‘The main issue is that you don’t know what it is. Surely, you must first know where it has come from.’ |

| Medication | ‘Yeah, it is literally hormone cream that you are using …’ ‘My understanding is that it's a medical cream so I think if it's not necessary, I prefer not to use it.’ |

| Worries | ‘I was really reluctant to use the cream all of the time, especially after reading the information leaflets about the cream.’ |

| Theme 2: Information about topical corticosteroids | |

| General practitioner (GP) | ‘The GP, in the beginning, is reluctant to prescribe the medicine, meaning that you having to return again and again because the treatment is not working and you’re not getting any further. Then, at a certain moment, you are referred on, and you get stronger medicine.’ |

| Paediatrician and dermatologist | ‘I would have really liked it if the doctors could have explained how to use the cream, however they didn’t, and they also didn’t make the time to do so.’ |

| Specialised nurse | ‘The appointment that I had with the specialist nurse was brilliant because she had plenty of time to answer all of my questions and explain things.’ |

| Leaflet | ‘I then become more anxious about the treatment instead of learning about it.’ |

| Internet | ‘If you start looking up everything on the internet, you end up finding all kinds of opinions, so I never do it myself.’ |

| Acquaintances | ‘Nobody will say to you: “Oh that's great for your child, make sure you apply it liberally”. In fact, everyone sticks to the conclusion that “it is still hormone cream”.’ |

| Contradiction | ‘I find it very confusing. The GP tells you to apply the cream thinly, while the dermatologist says that you must apply a thick layer.’ |

| Theme 3: Knowledge about topical corticosteroids | |

| Side effects | ‘The skin became much thinner as a result of the treatment, which then led to more breaking and therefore more infections of the skin.’ ‘The question I ask myself: What is the effect of the hormone cream over the long term?’ |

| Strength of topical corticosteroids | ‘And I knew about the hormone creams, strength one and two. And I also knew that those creams were the limit.’ |

| Composition | Some parents talked about ‘a kind of antibiotics’. |

| Lubrication schedule | ‘But I think that if I had known more about the importance of gradually cutting the dose and the logic behind it, I probably would have continued to use it.’ |

| Mechanism of action | ‘It helps, that's what I know.’ |

| Theme 4: Treatment with topical corticosteroids | |

| 4a. Additions and alternatives | |

| Alternative medicine | ‘We went to see a homeopath in the beginning when nothing was helping.’ |

| Other products | Thoughts on the anti-itch clothing: ‘And I believe that it is not proven to be helpful from a medical point of view. However, it was ideal, because our child could not get to the sensitive areas of skin.’ |

| Counteract possible causes | ‘Is it also something in the food?’ |

| 4b. Effectiveness | |

| Recurrent symptoms | ‘At this moment, I feel like the effect is becoming weaker. Because as soon as I start to reduce the amount, it comes straight back. Whereas in the beginning that didn’t happen.’ ‘So, you keep applying the cream, and it keeps coming back.’ |

| 4c. Practical usage | |

| Time consuming | ‘You become very frustrated with the process as it takes so much time. All you want is to find the solution straight away because it is all very upsetting.’ |

| ‘And then he/she has to sit still on the couch because the cream has to soak into the skin. That isn’t very nice.’ | |

| 4d. Adherence | |

| Dosage | ‘I did once ask: What exactly is a thin layer?’ |

| Lubrication schedule | ‘If it has gone, then it is gone. Then I also stop using the ointment. The dermatologist said that I must gradually cut the dose, but it is fine.’ ‘You might follow the schedule really well in the beginning.’ |

| Starting lubrication | ‘For example, if our child has a patch, then I will try the other cream first.’ |

The first theme concerned opinions about topical corticosteroids.

1a. Positive attitudeThe effectiveness of topical corticosteroids means that the availability of the ointment is regarded as a benefit by the parents. They indicated that they would have a problem if topical corticosteroids were unavailable.

1b. Negative attitudeThe parents’ attitudes towards topical corticosteroids were often negative. They thought it a disadvantage that topical corticosteroids only treat symptoms and not address the cause of atopic dermatitis. The participants felt resistance to topical corticosteroids because they were reluctant to use any medication on young children. Moreover, they stated that they had a fear of the hormones. The parents worried about the negative effects of topical corticosteroids and treatment duration. They thought this was caused by the strict instructions of general practitioners and other physicians, the negative influence of their environment, and the side effects mentioned in the leaflet.

2. Information supplyThe second theme concerned the information provided about topical corticosteroids. The parents stated that they received much contradictory information and sometimes did not know what to believe. They were often negative about general practitioners (GPs) because GPs are reluctant to prescribe topical corticosteroids and reluctant to refer to a dermatologist of paediatrician. On the other hand, parents observed that paediatricians and dermatologists encourage the use of topical corticosteroids, but often neglect to explain how the topical corticosteroids work or the importance of the lubrication schedule. The parents further indicated that they receive many suggestions from acquaintances regarding supplements. These acquaintances are often negative about the use of topical corticosteroids. In addition, the parents stated that there is little attention paid to topical corticosteroids at the well-baby clinic. The parents rarely referred to the leaflet provided or the internet to obtain information about topical corticosteroids.

3. Knowledge about topical corticosteroidsThe parents stated that they did not have much knowledge about topical corticosteroids: they barely knew the content of the ointment or the method of applying it. They thought that topical corticosteroids resulted in thinner and/or dryer skin, and that it hampers a child's growth. Some indicated that they have no knowledge of the side effects and do not observe them in their child. Many of the parents were provided with a lubrication schedule, but none of the parents could explain the importance of the schedule. Most of the parents did not know how to use the schedule, especially when to begin reducing the application of the ointment.

4. Treatment4a. EffectivenessThe parents indicated that the effectiveness of the treatment is good once the correct ointment has been identified. Sometimes, the effectiveness decreases when topical corticosteroids are used for a long time.

4b. AdherenceMost of the parents immediately began treatment with topical corticosteroids as soon as a lesion is visible, while others first use oily ointments. Most of the parents tried to apply a thin layer of topical steroids because this is what the doctor told them to do. However, the parents found it unclear how much ointment they should use for a thin layer. Even though some parents tried to initially follow the schedule, most parents stopped lubrication with topical corticosteroids when the lesion of atopic dermatitis became less visible. The reasons stated for stopping earlier than indicated were as follows: the schedule is not practical; the parents did not realise the importance; and the parents wanted to use topical corticosteroids as little as possible.

4c. Practical usageThe parents stated that some aspects make topical corticosteroids difficult to use. For example, it takes a long time to find the correct ointment, the application is time consuming, and the tube is small and fragile.

4d. Additions and alternativesIn addition to the topical corticosteroids, the parents used many other products. Nearly all the parents sought supportive measures to topical corticosteroids, and some of the parents also sought alternative treatments because they preferred not to apply topical corticosteroids.

DiscussionIn this focus group study, several important elements influencing low adherence were determined, such as insufficient knowledge regarding proper use, side effects, and method of use, especially reducing the dose. Moreover, the negative attitude of the parents is influenced not only by the reactions of lay people around the parents, but also by the remarks of healthcare providers, such as GPs.

Parental views and fears have been studied by others. A previous study using focus groups highlighted the concerns about side effects and parental desire to address the cause of atopic dermatitis.12 The study also demonstrated that corticophobia in parents is negatively affected by GPs, pharmacists, close acquaintances, and information from the internet.12 Smith assessed the information given to patients and patients’ parents from family, friends, and the internet about using long-term topical corticosteroids. Smith used a cross-sectional survey and found that patients and the parents of patients often receive non-informative risk messages from these sources.13 Farrugina also highlighted that a majority of patients and patients’ parents receive incorrect information regarding the dangers of long-term topical corticosteroids from pharmacists and GPs.14

The parents indicated that they did not understand when and how to reduce the medication, although some stated that this had been explained. They stopped the use of topical corticosteroids as soon as possible. This has never been described before.

We found that parents stop the application as soon as possible, that they are afraid of adverse effects, and that information on the medical leaflet makes them even more anxious. This is in line with Lee, who researched the negative influence of the internet, television or media, healthcare professionals, and magazines.11

The negative influence we identified stemming from the attitude of GPs confirms the results of a survey-study on Australian GPs’ perception of the safety of topical corticosteroids that unwittingly transmitted risk messages to parents.15 We found a discrepancy between the advice of paediatricians and dermatologists and those of GPs and other healthcare providers, such as well-baby clinic nurses. This discrepancy has been observed before.16

In our study, the parents not only wanted information about topical corticosteroids, but also information about alternative or complementary therapies and associated problems, such as allergies and asthma.

Several studies indicate that adequate information has a positive effect on corticophobia,10 Pustišek et al. studied the effect of structured parental education in a randomised controlled trial using questionnaires with the parents of children with atopic dermatitis.17 The intervention group received structured education immediately, and the control group following the second visit. During the second visit, the intervention group demonstrated a significant reduction in the level of stress and anxiety in parents and an improvement in the quality of family life. Heratizadeh studied the effectiveness of educational training in adult patients with atopic dermatitis using a randomised controlled trial.18 The intervention group was educated and displayed beneficial effects when compared with the waiting group with respect to psychosocial parameters and severity of atopic dermatitis.

The strength of our study is that through the formal use of focus groups all the factors surrounding corticophobia are found. One possible limitation is that this study was conducted with a group of parents whose children were treated in an outpatient hospital, and therefore may not be representative for parents of children with less severe atopic dermatitis. However, the group is representative regarding the caregivers of children who use topical corticosteroids the most and have the most complaints. Furthermore, due to the invitation process parents who attended the sessions might not be representative, e.g. all parents were of Dutch origin.

ConclusionsWe conclude that the treatment of atopic dermatitis can be improved by providing parents with more relevant information about the working mechanisms of topical corticosteroids: how to use them, how to reduce the dose, and why this is so important. It is important to discuss the fear of side effects and to explain what these are and that they rarely occur. There is a discrepancy between the views on topical corticosteroids of dermatologists and paediatricians on the one hand and other healthcare workers on the other. Healthcare professionals, especially GPs, need to be aware of the consequences of their negative attitude concerning topical corticosteroids. They should be educated in pathophysiology and the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.