This is a guide for grant application for researchers seeking research grants in the field of allergy and related diseases for the first time. It outlines how to organize proposals and the potential issues to be considered in order to fulfil the criteria of the funding bodies and thus improve chances of obtaining the desired funding when applying for a research grant. We will use this paper as an example of a grant proposal to be presented to the FIS “Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria” (Health Research Fund) of Spain. The general framework can be used for a research proposal to any funding agency. The main research designs are reviewed. Other topics such as hypothesis, objectives, methodology, ethics and legal issues, and budget are presented.

These guidelines seek to serve as a starting point for grant application for researchers seeking research grants in the field of allergy and related diseases for the first time. It outlines how to organize proposals and a number of issues which need to be addressed to satisfy the criteria of the funding bodies in order optimize chances of obtaining the desired funding.

When applying for research funding we will use this paper as an example of a successful first step grant proposal to be presented to the FIS “Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria” (Health Research Fund) of Spain. Nevertheless, the general framework can be used for a research proposal to any funding agency. We will also study comments made by the referees on the earlier proposal so that we can learn about what referees look for and how to improve the project proposal to optimize chances for successful funding.1

Preliminary stepsWriting a grant proposal can be a difficult task especially for an inexperienced researcher. Moreover, a grant request can be time consuming and frustrating sometimes. A well-written application is more likely to be funded than a badly written one.2 The best way to learn the art of grantsmanship is through the process of grant writing under the guidance of an experienced researcher.3 The proposal must be easy to read. If not carefully prepared, the proposal may be hard to read. If it is hard to read, reviewers will probably not really read it or at least they will not read it carefully enough to understand it. It is also true that your grant application is likely to be reviewed by people not very familiar with your research idea. Therefore, it is fundamentally important that your proposal be written clearly and simply to attract the interest of the reviewers. Use basic and grammatically correct English or Spanish and avoid typographical errors. The use of jargon, slogan and polemic should be avoided. Review the funding agency's guidelines carefully before beginning to write your grant proposal, and check to make sure your proposal fits the agency's eligibility criteria. Poorly prepared grant proposals which do not meet the standards or fit in with the priorities of the funding bodies, will be rejected. Therefore, it is important to provide pertinent information required by the funding agency for a positive decision.

The proposal must be in the format defined by the sponsor and conform to page limitation and it should include all required forms. Most granting agencies will not review a research proposal if all required forms are not included and properly completed.4 Some agencies require specific font sizes, margins and page sizes. If you do not meet these specifications, your application may be returned without review.

The first thing you need to do is to identify a clinical topic or question to answer. The best research ideas come from everyday clinical problems. If you do have any idea in mind, discuss it with colleagues in your field who are experienced and successful in acquiring research grants. Read the instructions for writing the grant application and compose it according to the guideline provided by the funding agency.

Make sure that your specific research aims can be accomplished within the proposed time and resources. Remember that experienced researchers in your field will evaluate your research grant proposal. A good quality research proposal provides evidence of the applicant's ability to successfully carry out the proposed research and it will ensure your grant application will be considered. Prior work relevant to the proposed project should be included. If a questionnaire or structured interview will be used, a copy must be included in the narrative rather than in an appendix. Since the proposal will be divided into sections, you need to be clear as to what information will go in each section.

Although writing a grant proposal may seem a waste of time, the investigator who invests a lot of time in developing a research proposal in advance, is an investigator who is more likely to complete the research. Another important reason for undertaking this process is that it makes it easier to write papers when the research is completed. Having a well thought out research idea and plan of attack will be greatly appreciated by the collaborative investigators.

Finally, the project funder will want to be told in the report that the project actually accomplished these objectives.

Components of a Grant ProposalThe Research proposal for the FIS has the following items

- 1.

First Page: Title, Principal Investigator, project duration in days, Proposal Abstract (objectives and methodology of the project)

- 2.

Antecedent and the state of the question.

- 3.

Project Statement

- 4.

Hypothesis

- 5.

Project Objectives

- 6.

Methodology (design, study population, variables, data collection, data analysis, limitation of the study.)

- 7.

Working Plan

- 8.

Research Team experience in the area. Developing an effective dissemination plan.

- a.

Project relevance either in its clinical impact or technological development.

- b.

Project relevance from a biometric point of view.

- a.

- 9.

Project Evaluation (assessing the value of work done based on the objectives set)

- 10.

Resources Available to carry out the project

- 11.

Budget Summary (detailed grounds or rationale for the requested budget.)

- 12.

Annex/Appendix

The title of the project is important. It sets the first impression. Along with the Abstract, it is one of the criteria used to route your application to the appropriate review committee and reviewers. You should choose a title that is descriptive, specific, appropriate, and should reflect the importance of the proposal. Ensure the title contains all the key elements of your research. A very short or a very long title is not recommended. Ensure that your title stays within the allowable character limits. If your title is too long, it may be truncated to the allowable length so that it can appear electronically. This could inadvertently change the entire meaning of your title. Do not underline or italicize your title.

AbstractThe abstract generally must fit into half a page, usually delimited by a rectangle on the form. The abstract is the most important part of the grant proposal because it is the first thing that reviewers will read, and it causes them to formulate an opinion of your proposal (good or bad, justified or not). The abstract should be written both in Spanish and in English. The abstract should be divided into two sections: objectives, and methodology of the project. The abstract (not more than 250 words in length) which should be a 'stand alone' document without references should contain a clear explanation of your research project for the reviewers to judge the nature and significance of your project. It should outline the purpose and the methods of your research. The abstract should mention something about each of the following topics: Subject, Purpose and Significance, Intervention, Location, and the Outcome.

The Purpose and Significance section should explain why the project is being done, what is to be accomplished and why it is important. In the Intervention or methodology paragraph, we should explain what will be done and what method will be used. In the Location sentence, where the research will take place should be described in sufficient detail. Lastly, the Outcome sentence should state the expected outcome of interest, for example, “to reduce childhood allergic symptoms''. The abstract should be written last once the entire grant proposal has been composed.

Background and SignificanceThe Background and Significance section states the research problem. State clearly here what has led to the identification of this problem and to the decision to conduct this research to address it. Demonstrate your familiarity of the chosen topic and specifically identify the gaps that the project is intended to fill. In addition, state the importance of the proposed research by relating the project's specific aims to the medical issue of allergy and related diseases. It is interesting to use epidemiological data such as those of mortality and morbidity to underline the importance of the topic. For example, “Asthma is the 3rd cause of hospital morbidity in Europe in children aged 1–4years and the 14th cause of mortality among European children aged 10–14years”

Conduct a literature search to critically evaluate previous research and existing knowledge relevant to your planned research. The literature review is therefore mandatory to help you to learn about the topic you are investigating, to determine to what extent your proposed research question has been previously researched by other scientists, as well as the method used. It will also help you to put your project and methodology into a relevant context. Moreover, it can let you avoid unnecessary repetition of work already done by other research scientists. This section convinces the reviewers that there is actually a problem which your project seeks to address.

Project justification and Research QuestionOne section refers to “project justification”. You should explain why the project is necessary: why this project should be financed instead of others. A successful grant proposal must identify a specific problem or need and make a strong case for the project's potential for direct impact in that area. Your proposal should also provide evidence that you have a thorough knowledge of the issues involved.

The research question should have a set of characteristics that are designated with the acronym FINER (Feasible, Interesting, New, Ethic, Relevant).

Specific Aims of the Research ProjectThis is the most important section of the grant application. As the term 'specific aims' implies, the aims of the proposed research need to be very precisely defined. Up to 45 % of grants will have an issue with the specific aims identified as a problem during peer review5. These critiques from reviewers include statements that the aims are overly ambitious, the aims are poorly focused, or the hypotheses are poorly stated. The Scientific Method of Experimentation is hypothesis-driven, thus, one makes an educated guess to explain a cause-and-effect relationship. Research is conducted to test this guess to obtain evidence that shows whether the hypothesis is true or false (there is no right or wrong).

HypothesisScientific hypothesis (an assumption that may be found to be true or false at the conclusion of the research study) should not be a prediction. The hypothesis should be specific enough to be experimentally tested.

There should be at least a general hypothesis and one specific hypothesis.

General hypothesisMust be clearly stated, preferably in one sentence for example, “Food Allergy Linked to Childhood Asthma”

Specific hypothesesHypotheses are more specific predictions about the nature and direction of the relationship between two or more variables. A well-thought-out and focused research question leads directly into hypotheses. Ideally, hypotheses should give insight into a research question and be testable (i.e. falsifiable in Karl Popper terminology)6.

The project should provide a rationale for the hypotheses explaining how they were derived and why they are strong. Furthermore, alternative possibilities for the hypotheses, as well as the reason for choosing the ones which will be studied in the project, rather than others, should be Provided.

ObjectivesList the project objectives and clearly describe the specific goals of the research, (for example your long-term goals are to find new treatments and ultimately to find cures for allergic diseases) including any hypothesis to be tested.

Main objectiveBegin with a one sentence summary of long-term goals of the funding programme. Then include a sentence stating the overall goals of this proposal.

Specific objectivesA great idea or a good main objective is not necessarily enough to satisfy funding agencies to fund projects. A successful grant proposal must describe a fully-developed project that puts the idea into action and has the potential to produce real results.

Ideally the proposal should have three main objectives (each in one paragraph), each based on one key hypothesis (which should be stated as such) with rationale and an indication of the experimental approach for each hypothesis. Make sure that the specific aims directly test your hypothesis and that the three objectives are integrated or well related to each other and to the overall goal, if not obvious, point this out to include a few concluding sentences on that page.

Research Design and MethodsThis section describes what you intend to do. Describe in detail the proposed method to be used to perform the research. The research design and methods section should clearly and specifically describe how you will accomplish your goals, and how you will answer your questions. As you can refer to standard methods, it is helpful to remember who is reading your grant. You should put sufficient detail here that your reviewer will understand your approach and be able to judge its value. If the reviewer is completely unfamiliar with your work, and your methodology is correct but the reviewer does not know it, you can still have your work rejected. You must be an expert, but you must also be persuasive.7

Description of the research design: the design can be an experimental laboratory design or epidemiological designs. (i.e. ecological study, observational, experimental, cross-sectional, case-study, longitudinal, etc). We will study briefly each of these epidemiological designs

Ecological StudiesAlso known as studies of group characteristics, ecological studies are studies which compare the rates of exposures and diseases in different populations using aggregate data on exposure and disease; this is in contrast to studies that investigate the characteristics of a disease or condition in an individual. The main advantage of this kind of study is that they are very cheap and easy to do because of the use of routinely collected data. They are useful for developing and screening new hypotheses about the causes of a disease, and providing new potential risk factors. For example, one study related the rate of tuberculosis in several countries with the prevalence of asthma symptoms, showing an inverse relation.8 These data suggested the hypothesis that a drug capable of enhancing tuberculin responses in allergic patients may lead to improvement of their clinical symptoms. Nevertheless, it has disadvantages; the main one is known as ecological inference fallacy or ecological fallacy. It is believed that the average value of the exposure studied and the average prevalence of a disease to all the individuals in a population. Furthermore, ecologic studies are subject to error because the quality of recording systems, access to health services, and diagnostic criteria, may differ between countries or provinces.

Cross-sectional studiesA cross-sectional study (often called a survey) is a study in which the presence or absence of disease and exposure variables are determined in each member of the study population or in a representative sample at a particular point in time. The difference with an ecological study is that the cross-sectional uses individual data, while the ecological study uses aggregated data. An example of a cross-sectional study is the ISAAC project: a cross-sectional study which measured the prevalence of asthma and allergies in childhood all over the world9. Cross-sectional studies are good for estimating prevalence and for formulating hypothesis and do not involve long-term follow up. Their main drawback is that diseases and potential risk factors are measured at the same time, so it is difficult to know if there is a causal relation (these are relatively weak studies for demonstrating a cause and effect relationship). For example in a cross-sectional study we could find that there is more asthma and allergic diseases among those people who do not have any pets (cats and dogs) at home compared with those who have them. It could be possible that not having pets at home was a consequence of having asthma and allergies and not a cause. Therefore, when a child has asthma her doctor asks him/her not to have any pets at home. For this reason a cross-sectional study does not prove whether the onset of disease or symptoms began before or after the exposure to risk factors.

Case Control StudyA case control study is a study where we collect information on exposition/exposure and risk factors of two groups of people. The group that has the disease or the risk factor are the cases and the group that do not have the diseases or the risk factor are the control. The purpose of the case control study is to find differences between the groups. The purpose of the case control study is to find differences between cases and control regarding risk factors. For example in a case control study, designed to explore the association of 'Childhood agricultural and adult occupational exposures to organic dusts in population-based case–control study of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)', 265 recently diagnosed patients were compared with 355 controls10. As in other designs like the cross-sectional study, one potential problem in the analysis is the existence of potential confounding factors11. In order to control for confounding variables in certain cases matched design is used. In this design controls are matched with cases by those variables which are potential confounders, usually age and sex. For example in a study to evaluate exposure to second-hand smoke in children with asthma, a matched case control design was used in 91 children with asthma matched to 91 healthy children12. If we use a matched design, we should include information about the matching arrangements, for example, cases were matched by gender, age and geographical location and the number of cases per control should be described when it is difficult to obtain a large number of cases. The information about the source for the controls: community controls or hospital patients should be included. In addition, it should be described if cases would be incident cases (new cases) or prevalent (existing cases). Case–control studies are cheap, easy to perform and fast, requiring smaller number of subjects than other studies. Their main problem is the existences of numerous biases and that a temporal sequence, essential to establish causal relation, cannot be assured.

Cohort studyIn a cohort study also known as a follow up study, two groups of subjects are selected from two populations and are classified into two groups: exposed; and not exposed, and they are followed or studied over a specific period of time in order to know the risk factors for the occurrence of an outcome, such as disease, adverse effects, or even death. For example, 2,671 women who met the criteria for persistent asthma, and had no prior diagnosis of COPD were asked in 2003 if they had used inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or not. They were followed for 5years to study their mortality rate13. Cohort studies can be prospective where the investigator has to wait until the outcome appears or retrospective when the outcome may have occurred before the beginning of the follow-up. For example, a researcher could look for relevant information in the clinical records in a Hospital from 20years ago to know if children have been breast-fed or not in order to study late incidence of asthma and allergies when the children were 6years old. Cohort studies have the advantage that there is a clear time relation between the suspected risk or cause and the outcome. Furthermore, they have fewer biases than case control studies. The main disadvantage of a cohort study is the big sample size, usually in thousands, it is expensive with potential losses to follow-up and in prospective cohort it takes a long time to complete the study in order to achieve the desire outcome. Of course, in a retrospective cohort a main issue is the quality of records. In our above example, if breastfeeding was not registered in clinical records it is impossible to perform the study.

Clinical TrialsA clinical trial is an experimental study which normally has at least two arms: a treatment arm and a control arm (although some have three arms or even more). In this way we test the new treatment versus the standard treatment. Although it is also possible that a clinical trial has several, or more than two arms, when we want to test several drugs or intervention at the same time. Patient allocation to each group should be random. A study with a control group and where patients were randomly allocated is a randomised clinical trial or RCT. Basically, the concept of blinding in clinical trials can be classified into three types. When the patient knows what medication he or she is taking, the study is an “open label” clinical trial. When the patient does not know his or her treatment assignment, the study is a blind clinical trial. When neither the patient nor the health care worker knows what drug the patient is taking, the study is a double blind. There is an additional refinement, triple blind, which means that the researcher and the person administering the treatment as well as the person who is analysing the data do not know the treatment or the intervention being given. In this way there would be no bias when analysing the data. For example: in order to know if oil intake during pregnancy has an effect on asthma, a population-based sample of 533 women with normal pregnancies were randomly assigned to 3 groups in the ratio of 2:1:1, to receive four 1-g gelatine capsules/d with fish oil providing 2.7g n-3 PUFAs, four 1-g, similar-looking capsules/d with olive oil or no oil capsules. Women were recruited and randomly assigned around gestation week 30 and asked to take capsules until delivery14. As there is the possibility that during the clinical trial one drug became clearly superior to the other, and it would be unethical to conduct a clinical trial that deprives half of the patients a better treatment. Sequential clinical trials are those where data are periodically analyzed on behalf of the ethics committee. If one arm is clearly superior to the other then the clinical trial must stop. When presenting a clinical trial, it is useful to adhere to CONSORT Statement15,16.

Ethical aspectsWhen human participants or experimental animals are used in the research, the researcher is required to obtain ethics approval prior to undertaking research. Informed consent (informed consent explaining the nature of the research and any risks and benefits to the participants must be described when the study includes human subjects) needs to be obtained. In some cases, certain study designs might not be ethical.

According to the Helsinki Declaration, Clinical Trials should be based on deep knowledge of updated scientific bibliography17. It is unethical to do unnecessary clinical trials when the research question could have been answered by a systematic review of the existing literature18. The need for a clinical trial should be justified in the Introduction, including a reference to a systematic review of previous clinical trials, or the absence of those trials19.

Legal aspectsYou should follow the laws of the country. For example in Spain when a research involves invasive procedures defined as any “intervention performed with research aims that involves physical or psychological risk” for the subject, or when biological samples are taken or stored, the law of Biomedical Research that requires informed consent as well as having the protocol approved by an Institutional Ethics Board should be applied20.

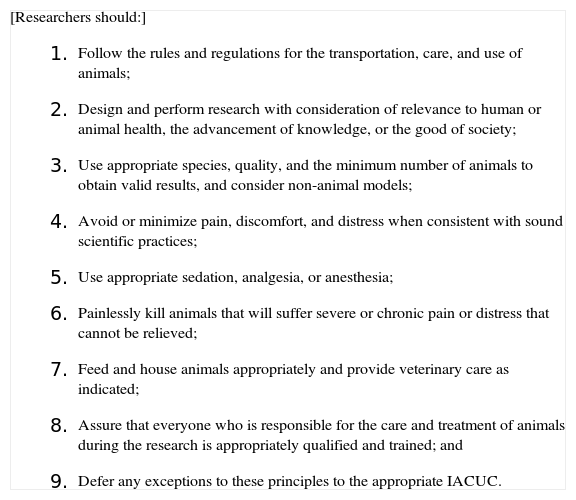

Animal studiesAnimal studies must conform to regulations (animal use protocol) for the safe and humane treatment of animals (you may briefly have to describe the animals to be studied and measures to minimise pain and discomfort). The use of animals must be reviewed by an Animal Experimentation Committee or an Agency and must fulfil international21, national22 and regional regulations23,24.

Basically, the policies for the utilisation of laboratory animals are concerned with minimising or alleviating animal pain and utilising alternatives to animal experimentation. This has been called “the three R's of animal experimentation”25 – Reduction, Refinement and Replacement.

The American Government has adopted nine Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals used in Testing, Research, and Training (Table I) These principles specify requirements for planning and conducting research and are useful to investigators26

US Government Principles for the Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research, and Training

[Researchers should:]

|

http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/references/phspol.htm#USGovPrinciples/

If 'bench' research will be carried out, the performance site must be a research lab. Methods to be used and the type of equipment required as well as the location of the laboratory must be specified in detail.

Study PopulationDescribe the study location (where the study is to be conducted) and the target population (i.e. age, gender, health status, economic status, family composition, race, ethnicity, geography, address, linguistics, etc.). Authors should report the number of settings involved. It is important to describe if the study is performed in one or several centres (“multicentre studies”). Any inclusion and exclusion criteria (those factors that allow some people to participate in a clinical study and disallow others) must be stated. Settings and locations affect the external validity of a trial. Health care institutions vary greatly in their organisation, experience, and resources and the baseline risk of the medical condition under investigation. Climate and other physical factors, economics, geography, and the social and cultural milieu can all affect a study's external validity.

Selection ProcessThis explains the process that will be used for selecting the cases from the population i.e: random sampling, stratified, cluster, consecutive sampling, etc.

VariablesThe authors should describe criteria for the selection of variables, and explain why certain variables were chosen for study and not others. In a descriptive study all variables to be studied should be enumerated. In an analytic study such as case–control, cohort or clinical trial, the authors should indentify the independent variables as well as the dependent variables. Potential confounding factors such as gender should be identified. Variables can be universal and so will be collected for all the individuals, or specific for certain subgroups.

Measurement units should be stated: weight, for instance, measured in kilograms and height in centimetres. Variables should be defined. For example, we consider as an asthmatic a patient who has a physician's diagnosis of asthma.

Data sources for variables should be explained: Observation (direct, physical exploration, laboratory examination), personal interview, questionnaire, clinical records, etc.

When laboratory measurements are used, the researchers should explain in which laboratory the determination will be made, or if they will be made in the same or different laboratories. Details need to be given as to when the determination will be made, who will do this, and who will calibrate instrumentation and when etc.

If a questionnaire is used it has to be referenced. The author should indicate when and where it was validated. If the questionnaire was translated from another language it should be specified if a back-translation was used. It is also important to mention if the questionnaire has been validated after the translation.

Sample size calculationsEstimated sample size must be stated. The proposal must include sample size justification. Normally the sample size sentence should explain what differences we seek to detect, the power (usually 80 %) and the confidence (normally 95 %). For example the proportion of controls will be 4:1 i.e. 4 controls for each case. In order to detect an Odds Ratio higher than 4 with a confidence of 95 % and a power of 80 %, and assuming a prevalence of the exposure in non-ill group 5 % a sample size of 315 persons (63 cases and 215 controls) would be needed. The software used for sample size calculations should be mentioned in the proposal.

Data CollectionInformation on how the data will be collected should be provided. If a postal survey is used, you should inform about how many surveys will be sent to the study subjects. When a study uses a physical examination the instruments brand and model should be provided, as well as the protocol for it use. For example a spirometry will be performed using a Datospir100 spirometer from Sybel®. Spriometry will be done using the SEPAR (Spanish Society of Pneumology and thoracic surgery) protocol.

Study design issues are the major problem for many studies. Statistical issues continue to plague the grants. Established investigators are particularly knowledgeable of statistical issues, whereas fellows and younger less established investigators may be less familiar with analytic issues or focused more on the project's interest than on feasibility. Mentors of the younger applicants should pay particular attention to this area. Grants with a qualified epidemiologist and an analytical plan fare better in general.

Endpoint definition“The predicted outcome” of the study that will be used should be explained, as well as its definition.

Data ManagementResearchers are responsible for taking appropriate precautions to protect the confidentiality of both participants and data. You should explain all measures taken to protect the confidentiality of research participants and study data. Quality control in data management should be stated: for example, double data entry was used to minimise typing errors.

Data analysisDescribe how data is to be collected, analysed and interpreted, including expected outcome of interest. Any test instrument should be clearly stated.

The techniques used in the statistical analysis should be described in depth. For example, variables will be tested for normality with the Shapiro test, if they have a normal distribution, Student'st-test will be used, and otherwise a non-parametric test will be used. Usually multivariate analysis should be used for all projects. When a non-standard or not well-known technique is to be used, it should be referenced, and also the reason for its use explained. A statistician may need to be consulted for advice if you have not taken a course in statistics.

Contingency Plans and Risk EvaluationDescribe the problems you expect to encounter and how you hope to solve them. For example, texts might be unavailable; people you had hoped to study might be unavailable or unwilling to participate, thus forcing you to select other interviewees or to change the focus; (Try to imagine every possible problem so that you have contingency plans and the project does not become derailed.)

Strengths and LimitationsThe project should evaluate its own internal validity (the extent to which conclusions about causes or relations are likely to be true by excluding interfering variables). In addition, its external validity (the degree to which the results of a study can be generalised to settings or samples other than the ones studied) if the results of the study can be useful. What are the strengths and limitations of your research method? Can others repeat it easily in your field or vicinity? Does it have applicability that is very important locally to other places/people? What is its external validity?-may these results be useful to other groups, other academicians and other students living elsewhere in the state/country/ etc? If this is so, how and to what extent?

Project PersonnelList the name and academic title of all the individuals or collaborator(s) who will be involved in your project. For example;

Principal Investigator (PI): The PI should be a faculty member (professor, associate professor, assistant professor, etc.) or a person with broad research experience. Previous participation as PI in other national or international research projects is important. His/her publication record, especially in journals with impact factor such as those included in the Journal Citation Report from ISI, mailing address, campus phone and fax numbers, and e-mail address should be included.

Co-investigators and study coordinators: Co-investigators and study coordinators may be faculty, staff, or students of the institution or other institutions (professor, associate professor, assistant professor, physician, nurse, research specialist, medical/graduate student, etc.) Their Curriculum Vitaes should be included as part of the proposal. If you select an individual to direct the project, summarise his or her credentials and include a brief biography in the appendix. A strong project director can help a grant decision.

The team should be multidisciplinary, with research experience and dedication. A multicentre team may also be interesting.

Resources Available to carry out the projectIn this section the PI should explain what resources he/she has available to contribute to the project: lab resources, equipment, computer-software, personnel etc.

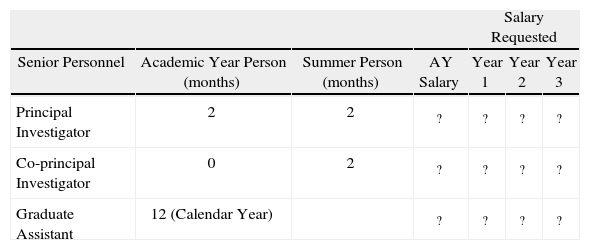

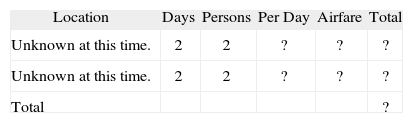

Budget Justification or Detailed grounds of the requested aid (1 to 2 pages)This indicates what resources are required to conduct your research and the cost of these resources. It usually consists of a spreadsheet or table with budget detail as line items and a budget narrative explaining the various expenses such as salary, travel cost to scientific meetings, printing and publications equipment and supplies, research assistants, software etc. It is important to note that salary and project costs are affected by the qualifications of the project personnel.

Be sure that all budget items meet the funding agency's requirements. An unrealistic budget is likely to lead to rejection of the proposal.

Personnel Section (Table II)Travel Section (Table III)Itemised Budget CostPublication

Films/Videos

Instructional Supplies

Lab Supplies

Multimedia Supplies

Periodicals and Publications

Reference Materials

Research Supplies/Materials

Subscriptions

Data Processing Supplies

Software Licenses

Other Supplies

Office Supplies

Copier Supplies

Computer Equipment

Printer Equipment

Office Equipment

Other Equipment

Computer Equipment

Printer Equipment

Fax Charges

Copier Supplies

Printing

Air Transportation

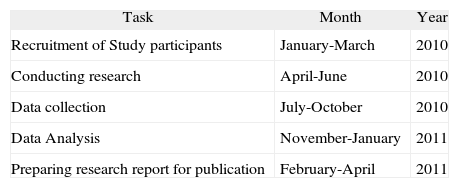

Set a timetable and give a detailed description of each task and provide an estimate of how long each task will take. As shown in the example below. Some projects may ask for the distribution of tasks among research team members (Table IV).

Annex/appendixSupplementary documents including letters, authorisation of the Research Institution, and the Institution Ethics Review Board of where the principal investigator works have to be included in the appendix.

How to Review an Unaccepted ProposalAn unaccepted proposal might be acceptable in a posterior resubmission. When the proposal is rejected it is important to ask for the referees' comments so that their criticism could be used to improve the proposal. Sometimes it is possible to question the reviewer's decision and gain the project's funding if the reviewer commits a major error. This is usually due to him/her not reading the proposal carefully, for example, the reviewer states that sample variables were not described in the project proposal and that, a copy of the questionnaire was not included in the project proposal, or he/she said that sample size calculation was not performed.