This study aims to evaluate the association between environmental and socio-economic conditions with asthma prevalence in the eight ISAAC centres in North-East Brazil.

MethodsEstimates on occurrence, severity and medical diagnoses of asthma in the previous 12 months were compared using environmental and socioeconomic indicators. Associations were assessed using simple linear regression and Pearson correlation coefficient.

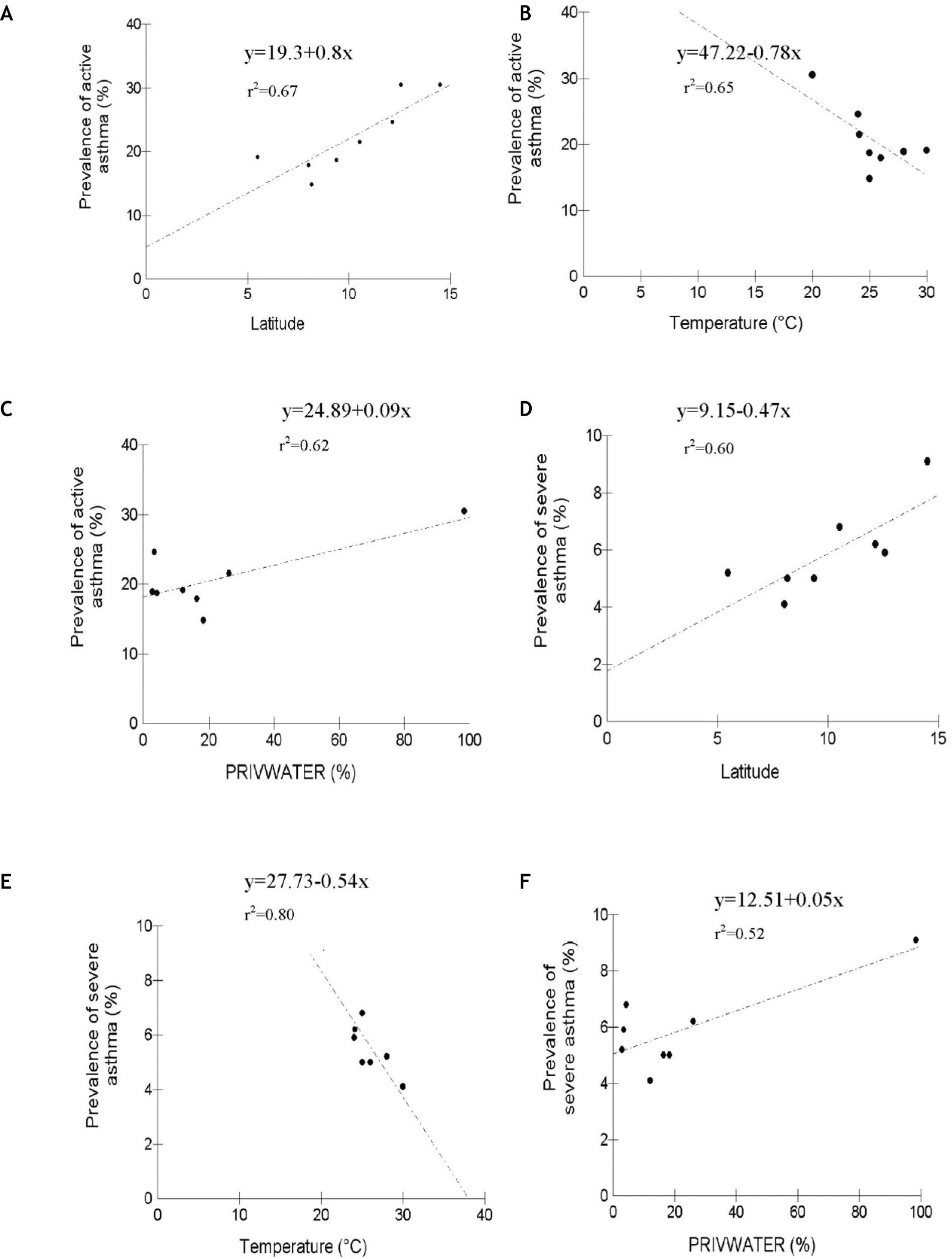

ResultsThere was no difference in asthma prevalence between centres. Active asthma prevalence increased with increasing water privation, and this would explain 62 % of the observed prevalence. Median temperature increase was inversely related to active asthma (r=0.81; p<0.05). There was a positive association between latitude and active asthma prevalence (r=0.82; p<0.005), a negative association between severe asthma and yearly medium temperature (r=−0.89; p<0.05), and a positive association with latitude (r=0.78; p<0.05).

ConclusionRelation between the tropical weather and high prevalence of asthma was not confirmed. There were associations with water privation and latitude.

To improve worldwide knowledge on asthma prevalence and its variation across different regions a uniform methodology of assessment was used in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) which was introduced in 1990. The same standardised questionnaire was used in all participant centres for children 6 to 7years of age and adolescents of 13 to 14years.1,2

ISAAC phase I demonstrated the wide variation in asthma prevalence, with higher estimates reported from Englishspeaking developed countries and from Latin America.3,4 The Phase III ISAAC initiative used the same methodology seven years later and demonstrated continued variation in prevalence and with significant prevalence increases (> 1 or 2 standard deviations) for at least one of the allergic conditions assessed in two thirds of participating centres.3,5 Such variability may be due to lifestyle, dietary factors, infections, socio-economic influences, climatic changes, diagnostic differences and management practices.6–9 For less developed countries, including countries in Latin America, fewer ISAAC studies have been undertaken.7,10,11

The association between high average environmental temperature and increased prevalence and severity of asthma has been well documented.8,12–16 Mallol et al.7 in Latin-American centres, reported this trend for hot and humid tropical climates. Some Brazilian participating centres in this study reported high prevalence also for locations with different climates and lower average temperatures.11 These differences, together with the large geographic diversity in Brazil, emphasise the need to study these variable associations within this large tropical country.

In this analysis, during Phase III of the ISAAC study, we examined the association between environmental and socio-economic conditions and asthma prevalence in the eight ISAAC participating centres in North-East Brazil.

Materials and methodsThe study was undertaken in 2002–2003 in the North-eastern region of Brazil (Fig. 1). The ISAAC methodology established by the ISAAC International Data Center11 was used in the following centres: Natal (Rio Grande do Norte), Recife and Caruaru (Pernambuco), Maceió (Alagoas), Aracaju (Sergipe), Feira de Santana, Salvador and Vitória da Conquista (Bahia).

All centres followed the same selection procedures (random stratified sampling), school questionnaire distribution, data collection and data processing methods approved by the Central Coordination Committee in New Zealand. The written questionnaires were previously validated for Portuguese Languag17 and for this report we considered the 13–14years group responses. All data were double entered in EpiInfo version 6.0. Ethical approval for the study was separately obtained for each centre.

Study variablesIn this study, we estimated asthma symptoms on the basis of positive answers to the written questions: “Have you had wheezing or whistling in the chest in the past 12months?”, this question indicates “active asthma”. The severity of asthma symptoms was assessed with the positive answers to the question: “In the past 12months, has wheezing ever been severe enough to limit your speech to only or two words at a time between breaths”. Lifetime asthma diagnosis was assessed with positive answers to the question “Have you ever had asthma?” Geographical and climatic data included latitude, average medium temperature (°C) and altitude and were obtained from IBGE.18

Socioeconomic characteristics were assessed using the Human Development Index (HDI), GINI index and Social exclusion index obtained from the cities socioeconomic data records.19 This last score was developed in 2002 to evaluate social exclusion and was considered to represent a poverty index. It includes the variables: water privation, which refers to the households without access to tap water (PRIVWATER), sewerage privation, the percentage of households without sewerage service (PRIVSEW), waste collection privation, percentage of households without regular waste collection (PRIVWASTE), percentage of population above 10years of age who are illiterate (PRIVEDUC) and the percentage of households with per capita average income of less than one dollar/day (PRIVINCOME).

Statistical analysisData in percentages were converted to arc-seno √p, to reduce variability and skewness. Associations were assessed using simple linear regression and Pearson Correlation coefficient.20 Prevalence of asthma categories (active, acute and diagnosed asthma) were the dependent variable, and independent variables were environmental conditions (yearly medium average temperature, latitude and altitude) and socioeconomic indicators (IES, PRIVWATER, PRIVSEW, PRIVEDUC, PRIVWASTE, PRIVINCOME, HDI and GINI). The Chi-square test was used to evaluate differences between centres. Data were analysed using BioEstat 2.0.21 The level of significance was 5 % (p < 0.05). Data in percentages (prevalence of asthma and socioeconomic indicators) were converted to arc-seno Öp…20

ResultsThe overall study compliance in each centre was good, with 87.3 % (IC95 % 79.4-95.1) of students fully completing the questionnaire. There was no difference between centres in prevalence of active asthma, severe asthma and diagnosed asthma (Table I). Prevalence of active asthma was not associated with average altitude variation or with the majority of socioeconomic indicators (Table II), except for PRIVWATER. Active asthma prevalence increased with increasing PRIVWATER, and this explained 62 % of the observed increase in prevalence (Table II, Fig. 2 C).

Prevalence of asthma and related symptoms in Northeast Brazilian centres participating in the ISAAC Phase III study

| Centres | Population | Participants | Positive responses | Active asthma | Severe asthma | Diagnosed asthma |

| Aracaju | 461,534 | 3043 | 568 | 18.7 | 6.8 | 15.4 |

| Caruaru | 253,634 | 3026 | 542 | 17.9 | 5.0 | 19.7 |

| Feira de Santana | 480,949 | 1732 | 373 | 21.5 | 6.2 | 5.8 |

| Maceió | 797,759 | 2745 | 406 | 14.8 | 5.0 | 13.8 |

| Natal | 712,317 | 1020 | 193 | 18.9 | 5.2 | 16.2 |

| Recife | 1,422,905 | 2865 | 548 | 19.1 | 4.1 | 18.0 |

| Salvador | 2,443,107 | 3020 | 744 | 24.6 | 5.9 | 13.7 |

| Vitória da Conquista | 262,494 | 1679 | 512 | 30.5 | 9.1 | 13.2 |

Chi-Square = 6.257; p > 0.05

Association between environmental and socioeconomic factors with prevalence of active asthma, severe asthma and diagnosed asthma in Northeast Brazilian centres participating in ISAAC Phase III

| Factors | Active asthma | Severe asthma | Diagnosed asthma | |||

| r | F | r | F | r | F | |

| Environmental | ||||||

| Mean temperature (°C) | −0.81 | 11.25* | −0.89 | 25.05** | 0.46 | 1.62 |

| Latitude South | 0.82 | 12.57* | 0.78 | 9.33* | −0.55 | 2.67 |

| Altitude (m) | 0.61 | 3.65 | 0.64 | 4.25 | −0.03 | 0.006 |

| Socioeconomic | ||||||

| IES (%) | 0.51 | 2.16 | 0.51 | 2.21 | −0.28 | 0.51 |

| PRIVWATER (%) | 0.79 | 10.03* | 0.72 | 6.72* | −0.23 | 0.34 |

| PRIVSEW (%) | 0.35 | 0.88 | 0.16 | 0.16 | −0.44 | 1.46 |

| PRIVWASTE (%) | 0.35 | 0.86 | 0.38 | 1.07 | −0.35 | 0.84 |

| PRIVEDUC (%) | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| PRIVINCOME (%) | 0.32 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 1.55 | −0.30 | 0.63 |

| HDI (%) | −0.47 | 1.43 | −0.39 | 0.91 | 0.38 | 0.89 |

| GINI (%) | 0.01 | 0.0008 | −0.64 | 2.08 | 0.60 | 1.69 |

r: coefficient of correlation; F: major variance/minor variance; IES: Social exclusion index; PRIVWATER: water privation; PRIVSEW: sewerage privation; PRIVWASTE: waste collection privation; PRIVEDUC: population above 10years of age illiterate; PRIVINCOME: households with per capita average income of less than one dollar/day; HDI: Human Development Index; GINI: GINI index.

There was a significant association between latitude and yearly average temperature (Fig. 2 A and B). Mean temperature increase was inversely related to active asthma (r = 0.81; p < 0.05). There was a positive association between latitude and active asthma prevalence (r = 0.82; p < 0.005).

Active and severe asthma showed comparable associations with altitude and yearly mean temperature, although the strength of these varied between the two asthma categories. There was a negative association between severe asthma and yearly average temperature (r = –0.89; p < 0.05), and a positive association with latitude (r = 0.78; p < 0.05), (Table II; Fig. 2 D, E and F). There was significant positive correlation between water privation and socio-economic variables (r = 0.72; p < 0.05; Table II).

There was no association of diagnosed asthma category with environmental or socioeconomic parameters (Table II).

DiscussionEnvironmental climatic conditions such as temperature and latitude were inversely related to asthma prevalence in these Brazilian North-eastern ISAAC centres, but an important socioeconomic indicator, water privation, was also directly correlated with prevalence. The influence of shortterm climate change on acute asthma exacerbations is well established,22,23 but the long-term influence of climate on disease occurrence is little studied. Previous reports have indicated that prevalence increased in places where temperature variation was small and yearly average temperature high.12–16 The North-East region in Brazil comprises nine states where a population of 50 million live in an area of 1,561,177 Km2 (18.3 % of the country area). A tropical climate predominates with large inland areas of semiarid land with dry weather, and much more humid coastal areas. There are marked socioeconomic disparities within this part of Brazil, which is considered the least developed and poorest region of the country. All the ISAAC centres, except for Vitória da Conquista (BA) and Caruaru (PE), were located in the coastal region where the majority of large cities in the region are located.

A relation between the tropical weather and high prevalence of asthma has been suggested by Mallol et al.16 Brazilian North-eastern ISAAC centres are located in an area where tropical climate predominates, but other environmental climatic conditions such as temperature and latitude were inversely related to asthma prevalence. This contradicts Mallol's findings, as asthma occurrence, and severe asthma prevalence, decreased with increase in annual mean temperature, in this tropical setting. Other geographic factors may explain these differences as the present study used centres which were coastally located, whereas the other study16 had a wide variation with centres dispersed across coastal and inland locations. The centres in the present study were in areas of high environmental humidity which can enhance mite and fungi proliferation, thus contributing to the increased risk of asthma. Studies from Australia and the Mediterranean have reported high house dust mite prevalence in households in coastal areas.25–28 In Singapore, with a tropical climate, increase in domiciliary humidity and child bed colonisation by dust mites were associated with increased allergic symptoms.28

The Hygiene Hypothesis would support the conclusion that the poor socioeconomic conditions in Northeast Brazil would be associated with decreased risk of asthma.29 The theory proposes that increased prevalence of gastrointestinal and parasitic infections, in young children and infants induces a protective effect through an enhanced type I, immune response.30 Intestinal parasitic infections are closely related to sanitary conditions and are an important public health problem in most developing countries. In Aracaju, North-East, Brazil we have shown31 a high enteroparasite prevalence in children attending day-care centres, although in Campina Grande which experiences high children asthma prevalence, Silva et al.32 found no association between asthma risk and ascariasis. It was not possible to assess enteric helminthiasis in the present study, although this information would have allowed a more detailed assessment of infection risk related to socio-economic status. Vitoria da Conquista had the highest active and severe asthma prevalence and is most distant from the Equator. It also has the lowest average temperature and highest social exclusion rates. These combined factors may explain the findings in this municipality.

As more factors related to the development of asthma are increasingly being recognised, epidemiologic studies in different locations are necessary in order to examine these factors and develop improved theories of causation. More detailed evaluation of other regions in Brazil is required in order to better understand the extent and diversity of these factors, the magnitude of the problem, and the role of socioeconomic and environmental factors in its natural history.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ISAAC study received support from CNPq (National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development), Brazil Ministry of Science and Technology. The authors thank Ms Jeane Vilar for support with the statistical analysis.