Telangiectasia macularis eruptive perstans (TMEP) was first described by Parker in 1930.1 It is a form of cutaneous mastocytosis, and is differentiated from other forms such as urticaria pigmentosa, solitary mastocytoma and diffuse or systemic mastocytosis by its refractory nature and/or lack of systemic associations. All forms have in common excessive accumulation of mast cells, whether localised to the skin or generalised to involve internal organs. It is clinically characterised by red telangiectatic macules, with hyperpigmented, subtle and discrete papules. Darier's sign is usually negative in patients with TMEP as opposed to other forms of mastocytosis in which it occurs. Lesions typically involve the trunk and extremities while facial involvement is rare.2,3

Currently no standard cure exists for mastocytosis but some cases may be self-limited and generally the lesions are refractory to treatment. Since TMEP is a rare diagnosis in the paediatric population4 the discussion of treatment is limited mostly to the numerous cases in adult ages.

Herein we report the case of a 4-year-old Caucasian male patient affected by TMEP, since he was 8 months old, successfully treated with Montelukast.

A 4-year-old male, was admitted to our Paediatric Department, University of Catania, for episodes of significant itchiness and cutaneous blistering, recurring since the age of 8 months, without the presence of other clinical symptoms.

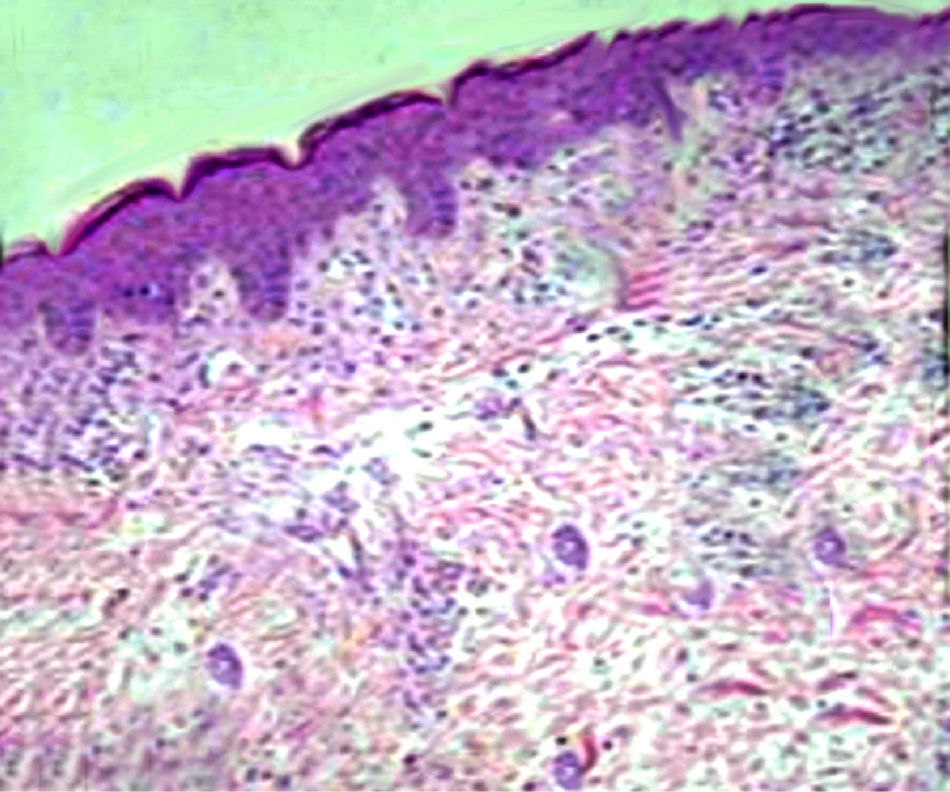

At admission, lesions were only localised on his face (Fig. 1a) and after 2 weeks they increased in number and spread to the trunk and limbs (Fig. 1b and c).

As far as his familial anamnesis was concerned, his parents and siblings did not show any positive history for atopic diseases and/or mastocytosis.

Physical examination revealed 3–10mm, erythematous macules that demonstrated densely packed, fine telangectases and slight hyperpigmentation. The lesions had sharply defined but slightly irregular borders. Stroking the lesions did not stimulate Darier's sign. The remainder of his physical examination was normal.

Blood analyses were all in the normal range, except for total IgE levels, being significantly increased (8518mmol/l, normal range: 98–110mmol/l).

To state the involvement of internal organs, chest X-ray, abdomen ultrasound scan and echocardiography were performed, and showed no sign of systemic disease.

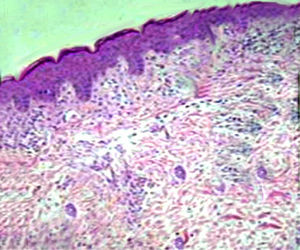

The child underwent dermatologic counselling, and physicians made a diagnosis of bullous atopic dermatitis. Thus, he started a therapy with topical corticosteroids, without resolution of symptoms. For the persistence of the skin lesions, a histopathological examination of a skin biopsy specimen, Giemsa stained, was performed and it showed diffuse capillaries ectasia and small superficial dermal inflammation, with a modest amount of perivascular lymphocytic plasma cells and an increased number of mast cells (Fig. 2). These findings were compatible with the diagnosis of TMPE.

The child started a therapy with anti-H1 antihistamine and oral corticosteroids at standard doses, without resolution of symptoms. Thus, oral Montelukast at standard doses (4mg/day) was added in therapy, and we observed a regression of the child's skin lesions. At follow-up visits he was continuing the treatment with Montelukast, without almost any new lesions and pruritus.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptive perstans (TMEP) is one of the rarest mastocytic disorders. Clinically it is characterised by reddish brown macules with telangiectases, usually involving the trunk, but also occurring on the face and extremities. The flushing begins abruptly and subsides spontaneously within 10–30min. Although flushing usually has a spontaneous onset, it can often be brought on by endogenous or exogenous stimuli that cause mast cell degranulation.1,5,6

Some references state that TMEP does not occur in children, but at least four children have been reported in literature. The first was a 10-year-old girl whose asymptomatic lesions began when she was 8 years old and slowly increased in number on the face and limbs. Some of the lesions disappeared over a 12–18-month period, according to the patient's family. There was no further follow-up.7 The second case was a 10-year-old girl whose lesions began when she was 7 years old. They first appeared on the upper trunk and slowly progressed to involve the face. In spite of the lack of systemic symptoms, the patient's 24-h urinary methyl histamine was 355mcg/g creatinine (normal 50–200). Due to physiological concerns, treatment with 585-nm flashlamp-pumped dye laser was utilised. There was an immediate wheal/flare response of all treated lesions during the procedure, which was markedly reduced when pre-treatment with doxepin and diphenhydramine was employed. On post-treatment biopsy, the therapeutic effect appeared to be limited to the vessels, with no apparent effect on the mast cells. Many of the lesions involving the trunk recurred within 14 months. There was no long-term follow-up.8

Chang et al., in 2001, made the hypothesis that the disease was based on autosomic dominant transmission, because TMPE was shown, during childhood, in people of three generations of the same family.3 As a matter of fact, in 2005, Neri et al. described a case of familial TMEP in a 23-month-old child, whose lesions were present since birth and were unchanged throughout life both in the child and in his siblings.9

In our case the child presented skin manifestations similar to those described in literature before, and they started when he was 8 months old. These manifestations occurred as episodes of flashing and they did not revert after antihistamines and corticosteroid therapy. Moreover his familial anamnesis was negative for TMEP and other forms of mastocytosis, excluding the familial form of the disease.

Since TMEP is a rare diagnosis in the paediatric population; the discussion of treatment is limited mostly to the numerous cases in adults which have a wide spectrum of severity. Currently no treatment exists for mastocytosis but some cases may be self-limited. The main goal of therapy is relief of symptoms and antihistamines are often beneficial. In severe cases H1 and H2 histamine receptor antagonists such as hydroxyzine, doxepine and cimetidine may help with pruritus, flushing and gastrointestinal symptoms. Oral sodium cromoglycate may also ameliorate gastrointestinal complaints. Psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) may be of benefit but its use on both adults and children is usually reserved for those with severe disease.10 Other treatment options include systemic and local corticosteroids as well as topical, intralesional and systemic interferon. Nevertheless TMPE generally tends to be persistent and unresponsive to treatment.

In 2009, for the first time in literature, Cengizlier et al. described a case of a 5-month-old boy with TMEP successfully treated with Montelukast at standard dosage.11 Cysteinyl leukotrienes (Cys-LTs) are potent pro-inflammatory mediators derived from arachidonic acid through the 5-lypoxigenase (5-LO) pathway. They exert important pharmacological effects by interaction with at least two different receptors: Cys-LT1 and Cys-LT2. By competitive binding to the Cys-LT1 receptor, leukotriene receptor antagonist drugs such as Montelukast, block the effects of Cys-LTs and alleviate the symptoms of many chronic diseases, especially bronchial asthma and allergic rhinitis. Mast cells produce and release a broad spectrum of mediators, including many pro-inflammatory chemoattractive and immunomodulatory cytokines. CysLT1 inhibitor MK571 and FLAP inhibitor MK886 decreased IL-5 and TNFα production after Fc¿RI stimulation, implying autocrine signalling by cysteinyl leukotrienes in mast cells.

Although no reported measurements of leukotrienes in patients with mastocytosis between or during clinical flares are available, in the case reported by Cengizlier, author observed an abrupt symptomatic relief after Montelukast was added in therapy.

To our knowledge this is the second case of TMEP successfully treated with Montelukast ever described in literature. The child's skin lesions were unresponsive to antihistamine and corticosteroid therapy at standard doses and we obtained a resolution of symptoms only when Montelukast was added to the therapy.

The long-term prognosis of TMEP is unknown because reported follow-up information of childhood cases is lacking. Currently, a standard protocol for the treatment of the disease does not exist. As it is a rare disorder, controlled studies evaluating efficacy of treatment modalities cannot be carried out and treatment is usually based on data evolving from case reports. We have achieved an abrupt clinical response through the use of Montelukast. Since there are only two reports on the use of Montelukast in TMEP, we could not suggest its standard use. Nevertheless, further studies could consider its efficacy and safety in paediatric patients affected by TMEP resistant to other therapies.