The prevalence of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is not well established, despite evidence of its occurrence in both minimal (MHE) and overt forms (OHE). Accurate diagnosis and management of HE can reduce morbidity and improve patients’ and their families' quality of life. This study aimed to systematically review the prevalence of HE in NCPH.

Materials and methodsSystematic research in five databases (MEDLINE, LILACS, MEDRXIV, SCIELO and Scopus) was carried out from January to April 2024 to detect studies that address the prevalence of MHE and OHE in patients with NCPH, using the terms: "Hepatic Encephalopathy" or "Psychometrics" or "Cognition Disorders" or "Cognition" and "Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension".

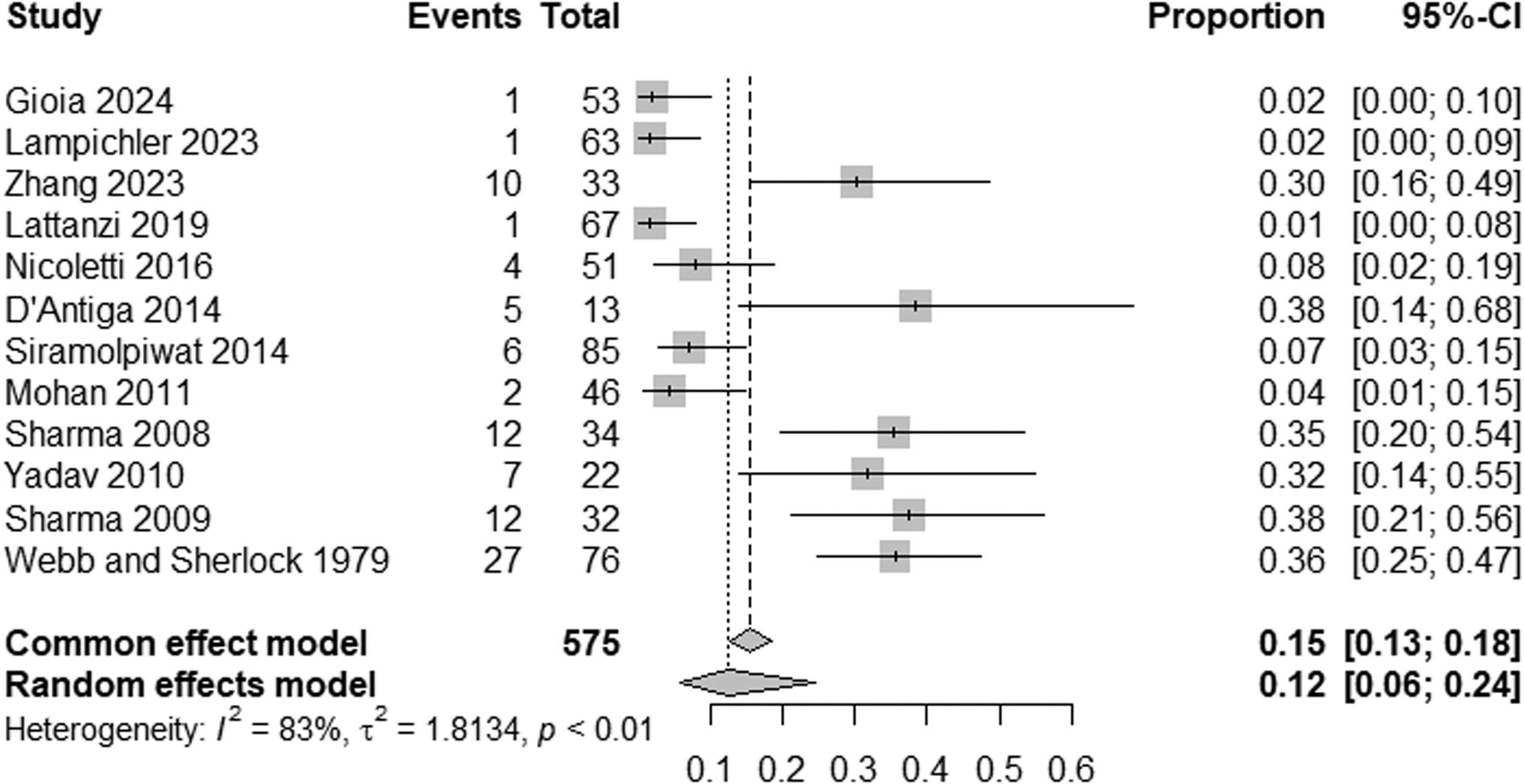

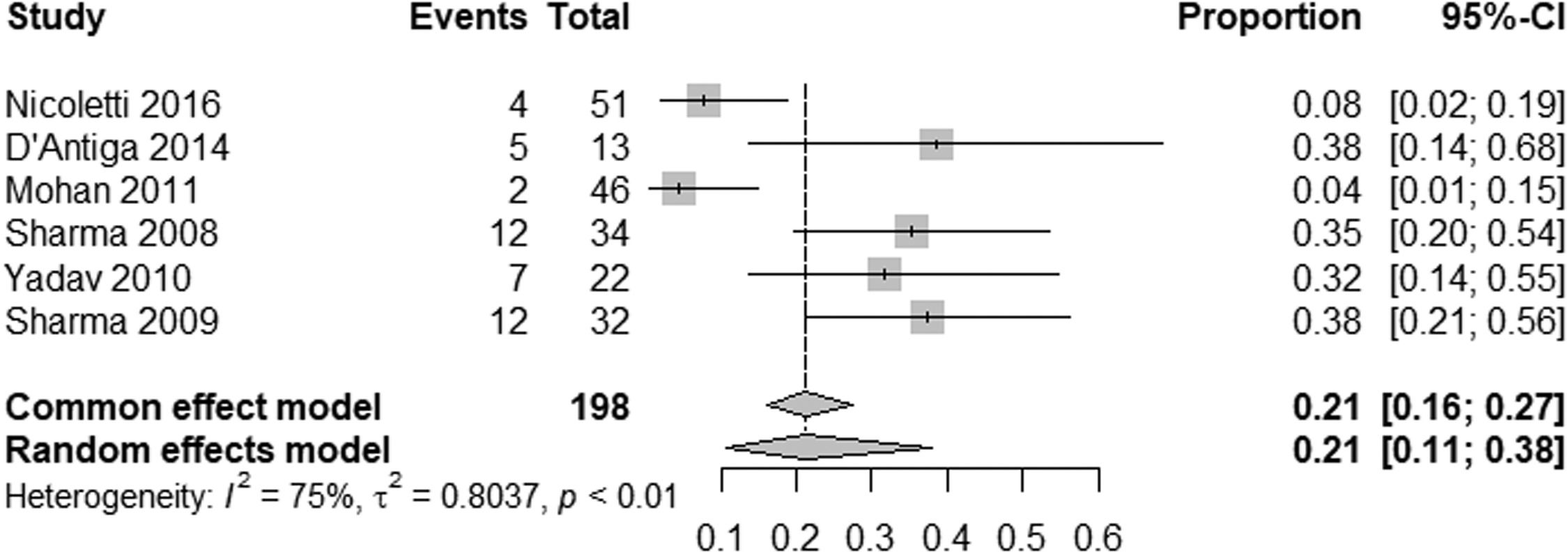

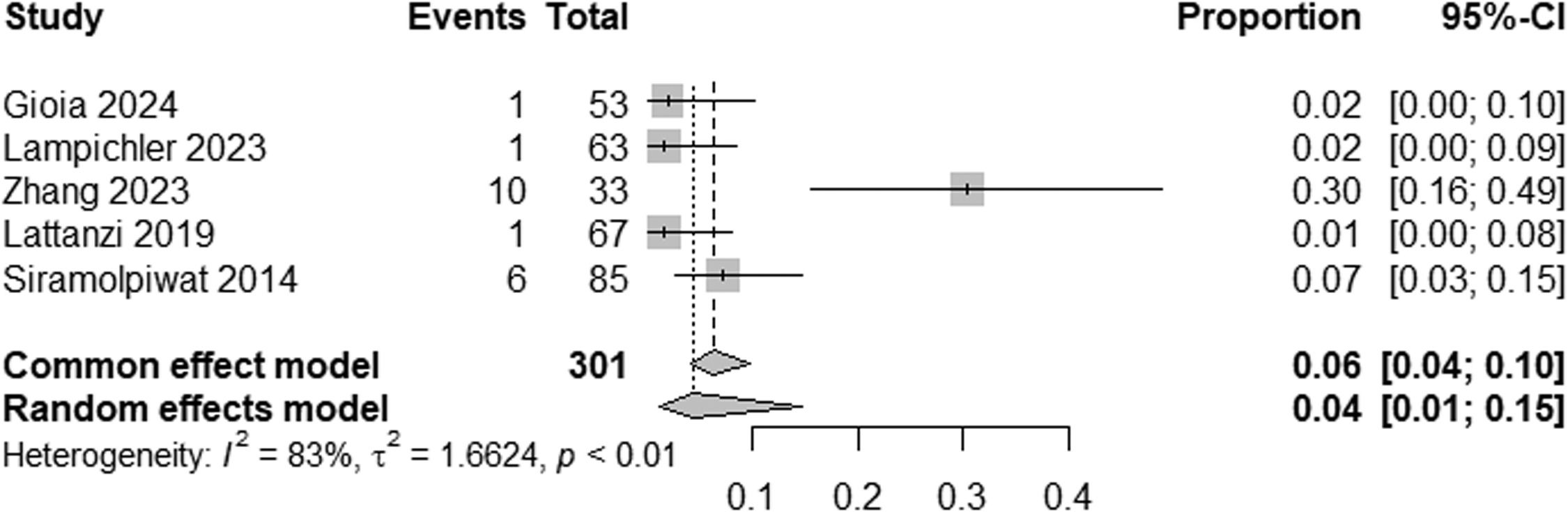

ResultsTwelve studies were included, including 575 patients. The prevalence of HE in patients with NCPH is 12 % (95 % CI: 6-24; I2 83 %, p<0.01), with high heterogeneity, with the pooled prevalence in studies evaluating MHE being 21 % (95 % CI: 11-38; I2 73 %, p<0.01) and the prevalence of OHE being 4 % (95 %CI: 1-15; I2 83 %, p<0.01). The prevalence of HE by etiology of NCPH is as follows: EHPVO is 25 % (95 %CI: 11-45; I2 0 %; p=1), PVT 2 % (95 %CI: 0-15; I2 0 %, p=1), in PSVD 8 % (95 %CI: 5-14; I2 87 %; p<0.01) and idiopathic NCPH 9 % (95 %CI: 5-14; I2 68 %, p<0.01), with the last two analyzes showing high heterogeneity.

ConclusionsHE occurs in approximately 12 % of patients with NCPH, with MHE being more common than OHE. Etiology plays a significant role in HE prevalence.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities caused by brain dysfunction related to liver failure and/or portosystemic shunting [1], from executive dysfunction to coma. The prevalence of HE in cirrhotic patients ranges from 20 % to 80 % [2], depending on whether minimal (MHE) or overt (OHE) forms are considered. While MHE is characterized by subtle neurocognitive changes detectable only through psychometric tests, OHE manifests with clinically overt neurological impairments [3,4], significantly affecting patients’ quality of life [5].

Non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) is defined by the presence of portal hypertension without histological changes of cirrhosis [6]. NCPH is an umbrella term encompassing diverse etiologies such as extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO), portal vein thrombosis (PVT), and porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder (PSVD). Additionally, NCPH predisposes patients to HE [7].

Despite its relevance, the prevalence and characteristics of HE in NCPH remain poorly understood [1,8]. Reported rates vary widely due to differences in diagnostic criteria, such as variations in the use of psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score (PHES), critical flicker frequency (CFF), and electroencephalograms (EEG) [9–12]. Several challenges have been identified in the utilization of these diagnostic tools, including variability in sensitivity and specificity across populations, the influence of educational background on psychometric test performance, and limited availability of neurophysiological assessments, such as CFF and EEG, in resource-constrained settings [13]. As a result, the characterization of HE in NCPH is hindered, which may lead to underdiagnosis or inconsistent prevalence estimates [14].

A recent meta-analysis reported significant heterogeneity in HE prevalence across studies [15]. Inconsistencies in studies’ methodologies, including population sampling strategies and inclusion of diverse NCPH etiologies, may contribute to this variability, highlighting the need for standardized diagnostic approaches and population-specific insights. This study seeks to systematically evaluate the prevalence of HE (both MHE and OHE) in patients with NCPH and explore potential associations with key clinical parameters, aiming to bridge critical knowledge gaps in this field.

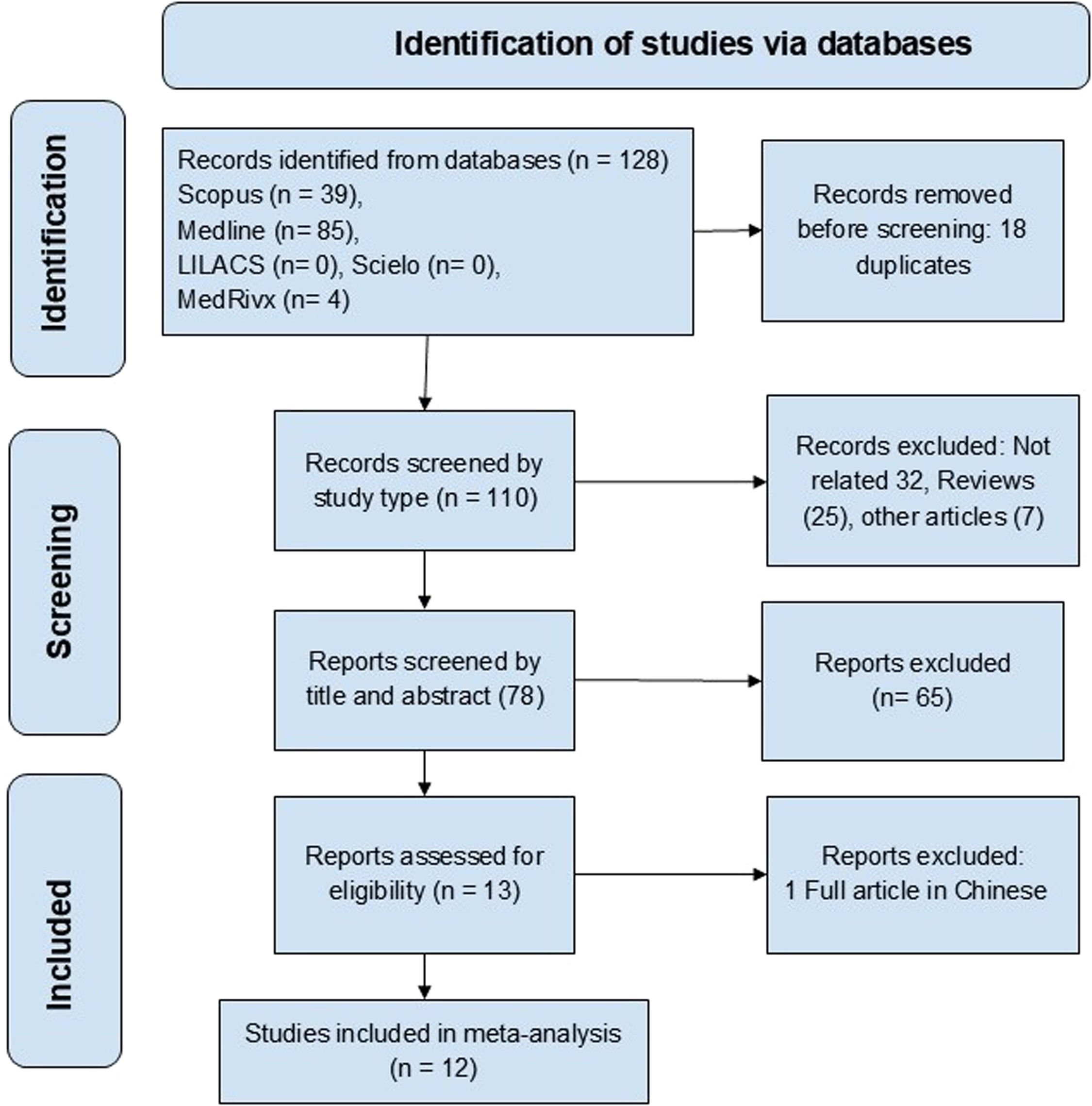

2Materials and methods2.1Study design and search strategyAn advanced, systematized, and independent search by two authors was conducted using MEDLINE, LILACS, MEDRXIV, SCIELO, and Scopus databases. The search strategy considered studies published from January 1975 to February 2024 in English, Portuguese and Spanish. It is important to note that the inclusion criterion was based on the publication date, not the research period covered by the studies. The following DECS health descriptors and Boolean descriptors were used: "Hepatic Encephalopathy" or "Psychometrics" or "Cognition Disorders" or "Cognition" and "Noncirrhotic Portal Hypertension". The entire study methodology was designed and executed to adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [16].

2.2Study selection2.2.1Inclusion criteriaThe eligible studies met the following criteria:

- 1.

Original clinical studies, including prospective or retrospective cohorts and cross-sectional studies, with a minimum sample size of 10 patients.

- 2.

Diagnostic Testing — Diagnosis of MHE based on neuropsychometric tests (psychometric hepatic encephalopathy score, number connection tests (NCT-A, NCT-B), or figure connection tests (FCT-A, FCT-B)), computerized tests (inhibitory control test, SCAN test, or Stroop test), or neurophysiological tests (critical flicker frequency, electroencephalogram, evoked potentials, or magnetic resonance spectroscopy).

- 3.

Participants diagnosed with NCPH confirmed by clinical, imaging, or histological findings [10].

- 4.

Reported prevalence of overt hepatic encephalopathy (OHE) and/or minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) as primary or secondary outcomes.

- 1.

Studies including patients with cirrhosis or acute liver failure.

- 2.

Case reports, letters to the editor, reviews, conference abstracts, and studies lacking sufficient prevalence data.

- 3.

Duplicated data or studies that reused previously published cohorts.

- 4.

Studies reporting the development of HE in NCPH after shunt surgery or endovascular procedures.

According to the selection criteria above, the titles and abstracts of all studies were independently reviewed by two authors. A third reviewer resolved any discrepancies.

2.3Data extraction and study quality assessmentThe data for this study was independently extracted by two reviewers using a standardized Excel form. The extracted variables included first author, publication year, study location, sample size, NCPH etiology, HE prevalence (OHE and/or MHE), and diagnostic methods (e.g., psychometric testing, clinical evaluation). Subsequently, the references of the selected articles were revised to cover a larger number of articles. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

2.4Additional analysisIn case high heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. These analyses aimed to assess the impact of variables such as NCPH etiology or type of hepatic encephalopathy diagnosed, whether overt or minimal, on the pooled prevalence estimates.

2.5Statistical analysisThe data were combined using random-effects meta-analysis models and presented as pooled proportions with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.3, meta-package version 7.0-0 [17]. Cochran's Q test and the I² statistic were used to determine the heterogeneity among the studies: I² values close to 0 % indicate no heterogeneity among the studies; I² values around 25 % indicate low heterogeneity; I² values around 50 % indicate moderate or substantial heterogeneity; and I² values near or above 75 % indicate high heterogeneity [18].

2.6Ethical statementsThis study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of publicly available data from previously published studies. As such, no primary data collection involving human participants or animals was carried out, and therefore no ethical approval or informed consent was required. Nevertheless, all the included studies explicitly stated that they had obtained ethical approvals and consents from their respective participants in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

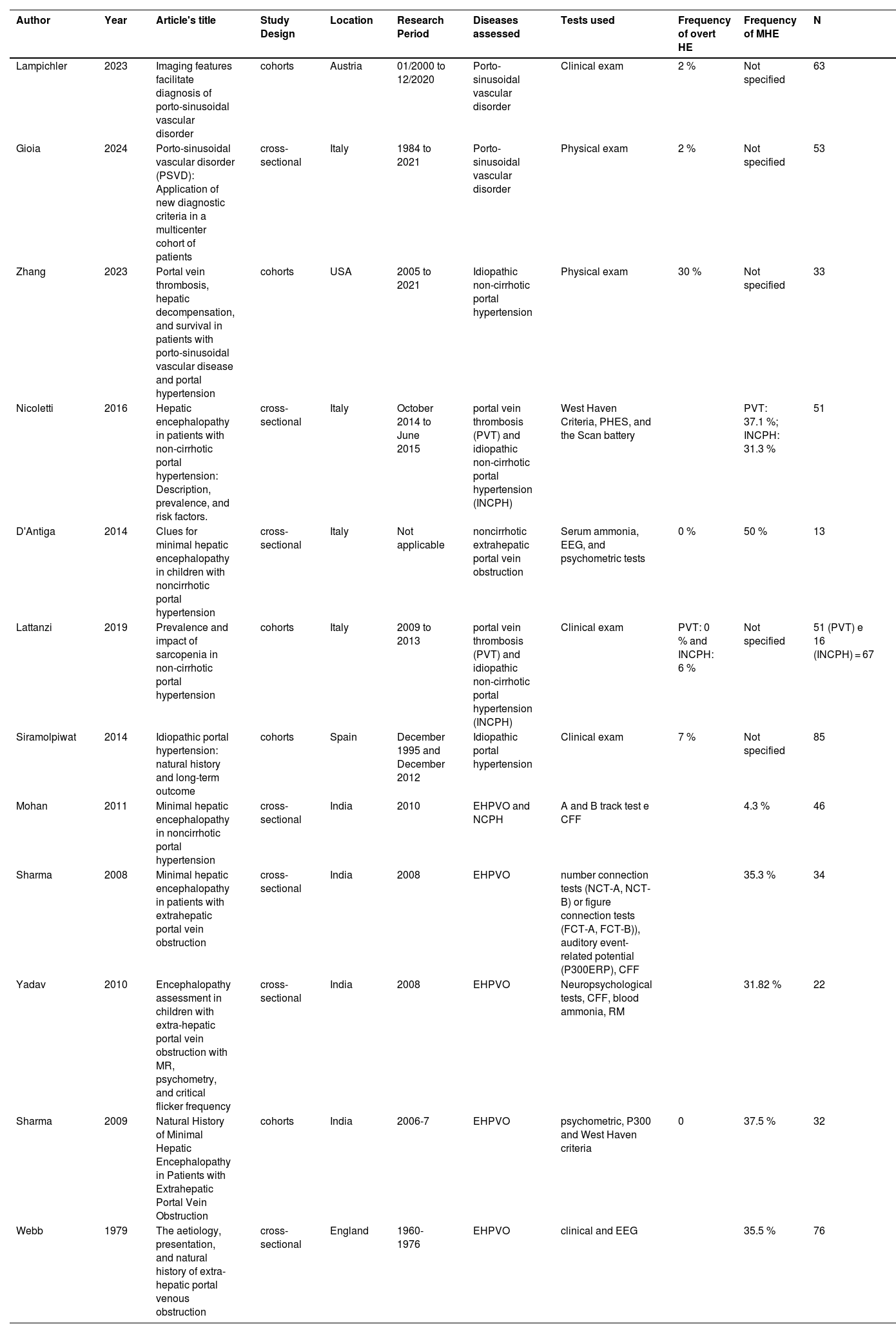

3Results3.1Study characteristicsThe search identified 128 articles, of which 12 studies met the selection criteria, covering 575 patients [11,12,19–28]. The studies’ selection and their inclusion or exclusion followed the PRISMA guidelines, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Table 1 summarizes the study characteristics, including geographic distribution, NCPH etiology, and diagnostic tools applied. Cohort and cross-sectional designs prevailed, with sample sizes ranging from 13 to 85 participants. The majority of studies focused on EHPVO and idiopathic NCPH, with fewer addressing PVT or PSVD.

Characteristics of the 12 studies included in meta-analyses about hepatic encephalopathy in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension.

| Author | Year | Article's title | Study Design | Location | Research Period | Diseases assessed | Tests used | Frequency of overt HE | Frequency of MHE | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lampichler | 2023 | Imaging features facilitate diagnosis of porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder | cohorts | Austria | 01/2000 to 12/2020 | Porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder | Clinical exam | 2 % | Not specified | 63 |

| Gioia | 2024 | Porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder (PSVD): Application of new diagnostic criteria in a multicenter cohort of patients | cross-sectional | Italy | 1984 to 2021 | Porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder | Physical exam | 2 % | Not specified | 53 |

| Zhang | 2023 | Portal vein thrombosis, hepatic decompensation, and survival in patients with porto-sinusoidal vascular disease and portal hypertension | cohorts | USA | 2005 to 2021 | Idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension | Physical exam | 30 % | Not specified | 33 |

| Nicoletti | 2016 | Hepatic encephalopathy in patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: Description, prevalence, and risk factors. | cross-sectional | Italy | October 2014 to June 2015 | portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (INCPH) | West Haven Criteria, PHES, and the Scan battery | PVT: 37.1 %; INCPH: 31.3 % | 51 | |

| D'Antiga | 2014 | Clues for minimal hepatic encephalopathy in children with noncirrhotic portal hypertension | cross-sectional | Italy | Not applicable | noncirrhotic extrahepatic portal vein obstruction | Serum ammonia, EEG, and psychometric tests | 0 % | 50 % | 13 |

| Lattanzi | 2019 | Prevalence and impact of sarcopenia in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension | cohorts | Italy | 2009 to 2013 | portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (INCPH) | Clinical exam | PVT: 0 % and INCPH: 6 % | Not specified | 51 (PVT) e 16 (INCPH) = 67 |

| Siramolpiwat | 2014 | Idiopathic portal hypertension: natural history and long-term outcome | cohorts | Spain | December 1995 and December 2012 | Idiopathic portal hypertension | Clinical exam | 7 % | Not specified | 85 |

| Mohan | 2011 | Minimal hepatic encephalopathy in noncirrhotic portal hypertension | cross-sectional | India | 2010 | EHPVO and NCPH | A and B track test e CFF | 4.3 % | 46 | |

| Sharma | 2008 | Minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with extrahepatic portal vein obstruction | cross-sectional | India | 2008 | EHPVO | number connection tests (NCT-A, NCT-B) or figure connection tests (FCT-A, FCT-B)), auditory event-related potential (P300ERP), CFF | 35.3 % | 34 | |

| Yadav | 2010 | Encephalopathy assessment in children with extra-hepatic portal vein obstruction with MR, psychometry, and critical flicker frequency | cross-sectional | India | 2008 | EHPVO | Neuropsychological tests, CFF, blood ammonia, RM | 31.82 % | 22 | |

| Sharma | 2009 | Natural History of Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in Patients with Extrahepatic Portal Vein Obstruction | cohorts | India | 2006-7 | EHPVO | psychometric, P300 and West Haven criteria | 0 | 37.5 % | 32 |

| Webb | 1979 | The aetiology, presentation, and natural history of extra-hepatic portal venous obstruction | cross-sectional | England | 1960-1976 | EHPVO | clinical and EEG | 35.5 % | 76 |

The pooled prevalence of HE in NCPH was 12 % (95 % CI: 6-24; I² = 83 %, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Subgroup analysis indicated an MHE prevalence of 21 % (95 % CI: 11-38; I² = 75 %, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3) and an OHE prevalence of 4 % (95 % CI: 1-15; I² = 83 %, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4). The wide confidence intervals for minimal HE (95 % CI: 11–38) and overt HE (95 % CI: 1–15) reflect the high heterogeneity among the included studies.

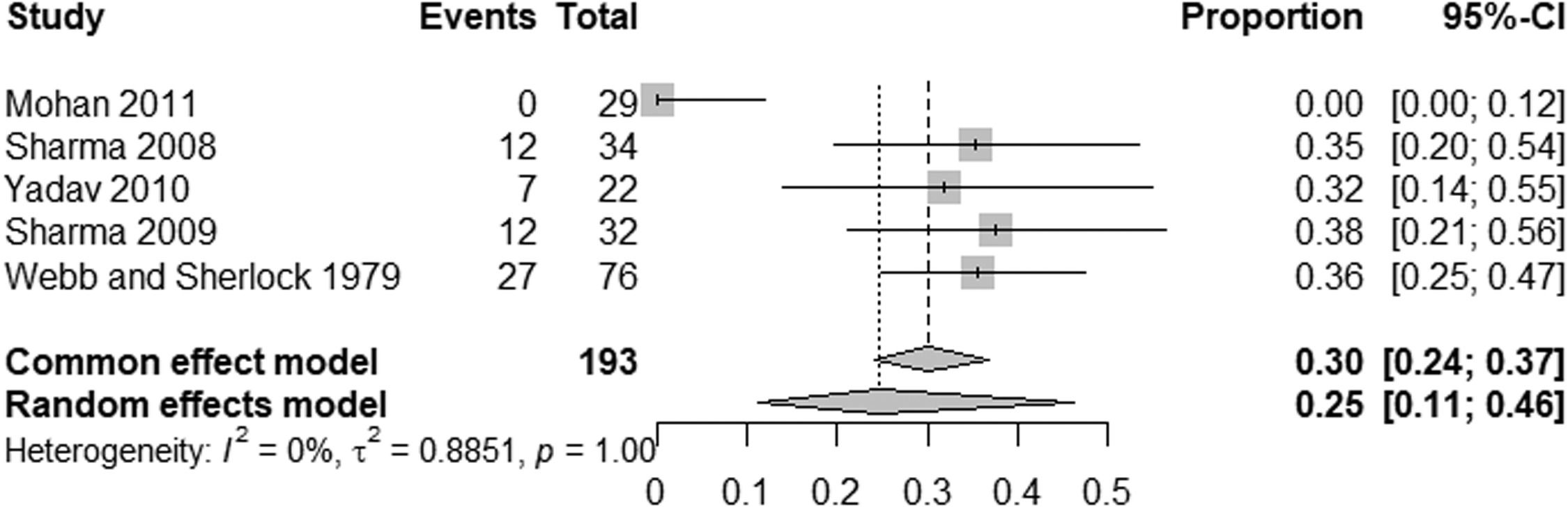

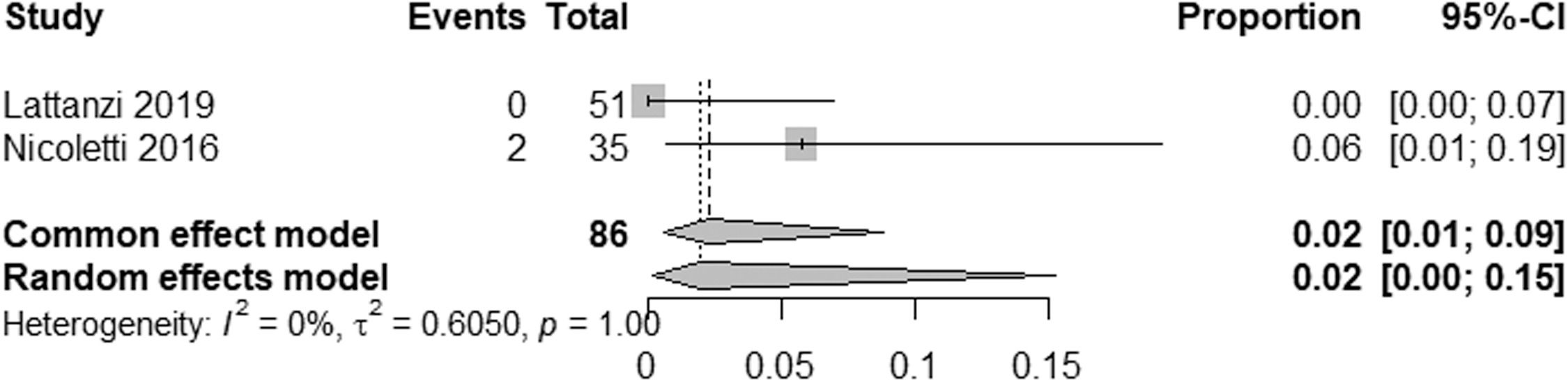

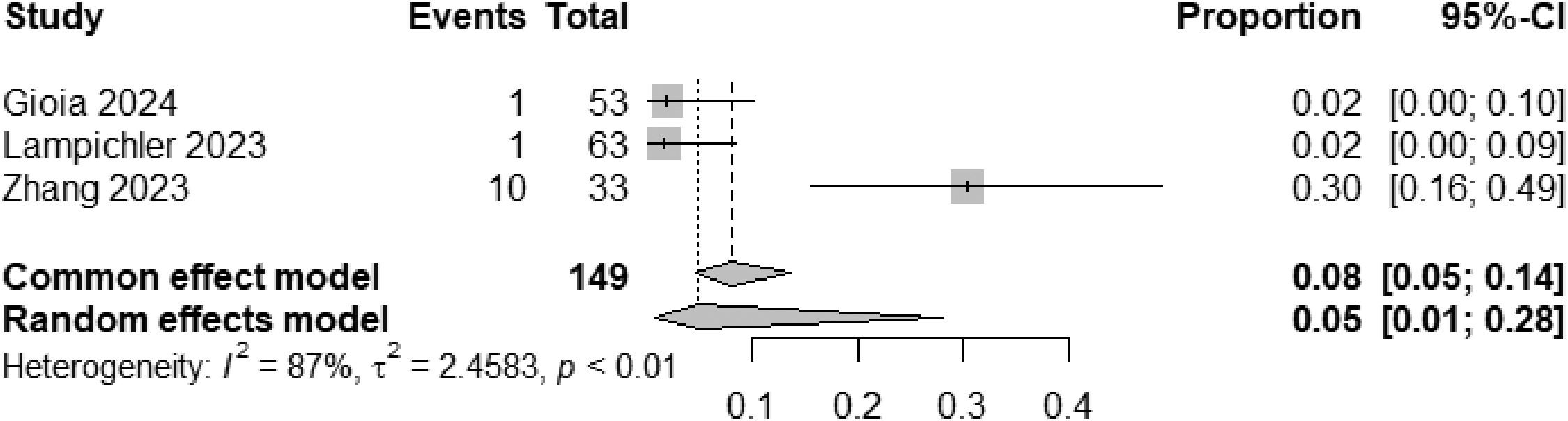

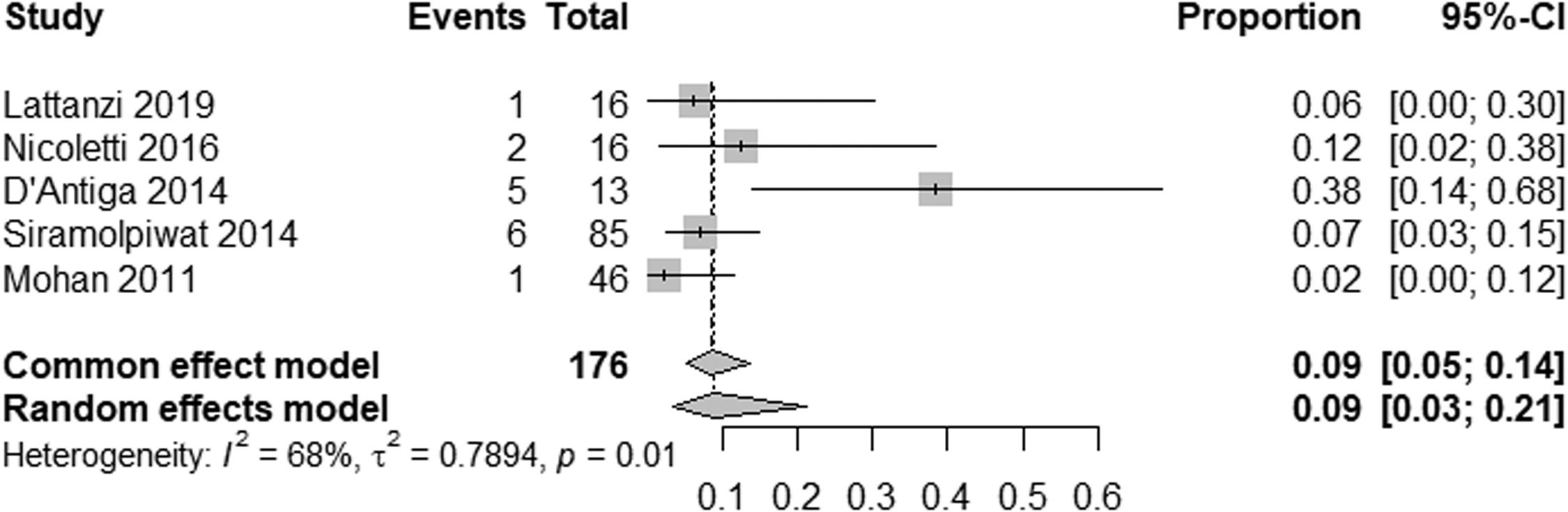

EHPVO exhibited the highest HE prevalence (25 %; 95 % CI: 11-45, I² = 0 %; p = 1) (Fig. 5), while PVT had the lowest (2 %; 95 % CI: 0-15; I² = 0 %; p = 1) (Fig. 6). The unexpected homogeneity (I² = 0 %, p = 1) in particular subgroups warrants consideration of the specific characteristics of these subsets, which may have minimized sources of variation or could also reflect a low statistical power due to the small amount of studies inside of those subgroups. For PSVD, the prevalence of HE was 8 % (95 % CI: 5-14; I² = 87 %; p < 0.01) (Fig. 7). Lastly, in studies examining INCPH, the prevalence of HE was 9 % (95 % CI: 5-14; I² = 68 %; p < 0.01) (Fig. 8). Significant heterogeneity was observed across subgroups.

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified hepatic encephalopathy (HE) in 12 % of the patients with NCPH, with a prevalence of 21 % for minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) and 4 % for overt hepatic encephalopathy (OHE). This prevalence rate highlights the clinical relevance of HE even in non-cirrhotic contexts, suggesting that early identification and treatment could mitigate cognitive impairments and improve the quality of life of affected patients.

The findings of our study align with prior observations indicating that HE in NCPH differs significantly from HE in cirrhotic patients. In cirrhosis, OHE prevalence ranges from 11 % to 30 % [30–32], while MHE is reported in 24.6 % to 80 % of cases [33–36]. Unlike cirrhotic patients, those with NCPH have their liver function preserved, with the development of HE primarily associated with portosystemic shunts. According to the AASLD/EASL Practice Guidelines, this form of HE is classified as type B1. Although its prevalence and severity are generally lower in NCPH, diagnosing and treating HE is critical due to its impact on the patient's quality of life, socioeconomic productivity, and safety [5,37,38].

Heterogeneity resulted from the variability in diagnostic methods and population characteristics. Studies using psychometric tests demonstrated increased sensitivity for detecting MHE [11,12,22,23,26,27], while reliance on clinical criteria [19–21,24,25] alone probably underestimated prevalence rates. The substantial heterogeneity observed among studies reflects the diverse conditions encompassed by NCPH, which primarily affect the liver vascular system [29]. However, when stratified by etiology, the prevalence rates of HE showed less heterogeneity, ranging from 2 % to 25 %.

Our results also highlight a significant variability in HE prevalence across NCPH etiologies. For example, studies on extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) reported the highest prevalence of HE (25 %), consistent with findings in patients with or without prior shunt surgery [39]. In contrast, HE prevalence in portal vein thrombosis (PVT) without cirrhosis was only 2 %. Interestingly, neuropsychological and encephalic imaging abnormalities in PVT patients have shown similarities to cirrhotic HE, suggesting shared pathogenic pathways [7].

Studies using the new nomenclature "porto-sinusoidal vascular disorder" (PSVD) reported an 8 % prevalence of HE [19–21], very close to studies referring to the term “idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension” (INCPH), which showed a prevalence of 9 %. This consistency supports the adoption of the PSVD terminology to unify the classification of these heterogeneous conditions [40]. The high heterogeneity observed in studies under the INCPH label may possibly reflect the diverse underlying causes and histological findings.

Regarding Schistosoma mansoni, a common cause of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension (NCPH) in endemic regions of South America and Africa [41], no studies reporting the prevalence of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) were identified in our systematic review. However, clinical reports have documented episodes of HE following procedures such as transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) [42] and gastrointestinal bleeding [43]. Additionally, an experimental study involving infected animals fed a high-protein diet demonstrated the potential for severe HE [44]. Although these studies were not included in our meta-analysis, they highlight the importance of further research to better understand the burden of HE in patients with schistosomiasis-associated NCPH, particularly given its status as a neglected tropical disease. The results of our study differ from those reported in a recent meta-analysis, which included 25 studies with 1487 patients and found a pooled prevalence of MHE in NCPH patients at 32.9 % and an OHE event rate of 1.2 % [15]. Methodological variations and less strict inclusion criteria may contribute to the broader inclusion of EHPVO studies, leading to a higher prevalence of HE. Despite these distinctions, both analyses highlight the substantial HE burdens across various NCPH populations and emphasize the need for standardized diagnostic criteria and consistent reporting.

5ConclusionsThis meta-analysis demonstrates that, although less frequent in NCPH than in cirrhosis, HE remains a recurrent complication with significant impact on patients’ quality of life and safety. The diagnostic challenges and variability in reported prevalence emphasize the need for future research to refine diagnostic criteria and elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying HE across different NCPH etiologies. These strategies should include routine screening for MHE using validated psychometric tests in NCPH patients.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The researchers fully funded the study themselves.

CRediT authorship contribution statementIris Campos Lucas: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Edmundo Pessoa de Almeida Lopes Neto: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Norma Arteiro Filgueira: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Caroline Louise Diniz Pereira: Data curation, Investigation. Thais Campos Lucas: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Ana Lúcia Coutinho Domingues: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.