Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the most common liver disease affecting people's health, with its incidence increasing year by year. This study aims to determine the effects of Health Action Process Approach (HAPA)-based health management on patients diagnosed with MASLD.

Patients and Methods204 MASLD patients were selected from the hospital's physical examination center from January 1, 2023, through April 1, 2023. Patients are randomly assigned to two groups (n = 102 each) using an envelope-based. Individuals in the experimental group received case management based on the HAPA theory, while standard health management was employed for control group patients. All subjects were monitored over a 6-month period, comparing body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), levels of liver function (AST, ALT), blood lipid levels (total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and health behaviours (as assessed with the HPLP-II health promotion lifestyle scale) before and after the intervention.

ResultsPost-intervention, the experimental group showed significant improvement in fatty liver (P < 0.01) and reductions in biochemical indices, BMI, and WHR levels (P < 0.05), and a corresponding improvement in HDL-C levels (P < 0.001), compared to the control group. Additionally, patients in the experimental group exhibited significantly better health behaviour scores related to stress management, exercise, diet, and health responsibility compared to controls (P < 0.01).

ConclusionsHAPA theory-based case management can improve blood lipid profiles, liver function, and health-related behaviours in MASLD patients, highlighting its potential as an effective management strategy for this condition.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined by evidence of steatosis in > 5 % of liver cells despite the absence of excessive alcohol intake (≥30 g/day and ≥20g/day in males and females, respectively). NAFLD and many other forms of chronic liver disease are associated with pronounced metabolic dysfunction and are related to other metabolic risk factors such as obesity and type 2 diabetes [1]. In order to better reflect the etiology of NAFLD and its co-existence with other metabolic diseases, the term metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) was proposed in 2020 [2]. Subsequently, in 2023, three major multinational liver associations proposed that the term “metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)” should replace “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)” [3]. Emerging evidence indicates that there is excellent consistency between the definitions of NAFLD and MASLD - that is, approximately 99 % of patients with NAFLD meet the MASLD criteria [4]. Therefore, the two definitions can be used interchangeably. According to the survey, the incidence of MASLD has reached about 30 % in the world [5]. In addition, 37 % of MASLD patients have progressed to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, which can lead to cirrhosis [6]. However, to date, no specific pharmacological treatments for MASLD have been established to date [7], and affected patients can undergo non-pharmacological, pharmacological, and/or surgical disease management [8]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines [9] recommend lifestyle changes as the first treatment for people with MASLD. Nonetheless, only 30 % of MASLD participants can lose weight through lifestyle changes, so improving lifestyle adherence and establishing long-term health behaviors is an important challenge for MASLD [10]. Therefore, this study aims to investigate improvements in liver function through special nursing interventions, as well as the generation and maintenance of health-promoting behaviors in patients, to provide a reference for the clinical development of health management programs for patients with MASLD.

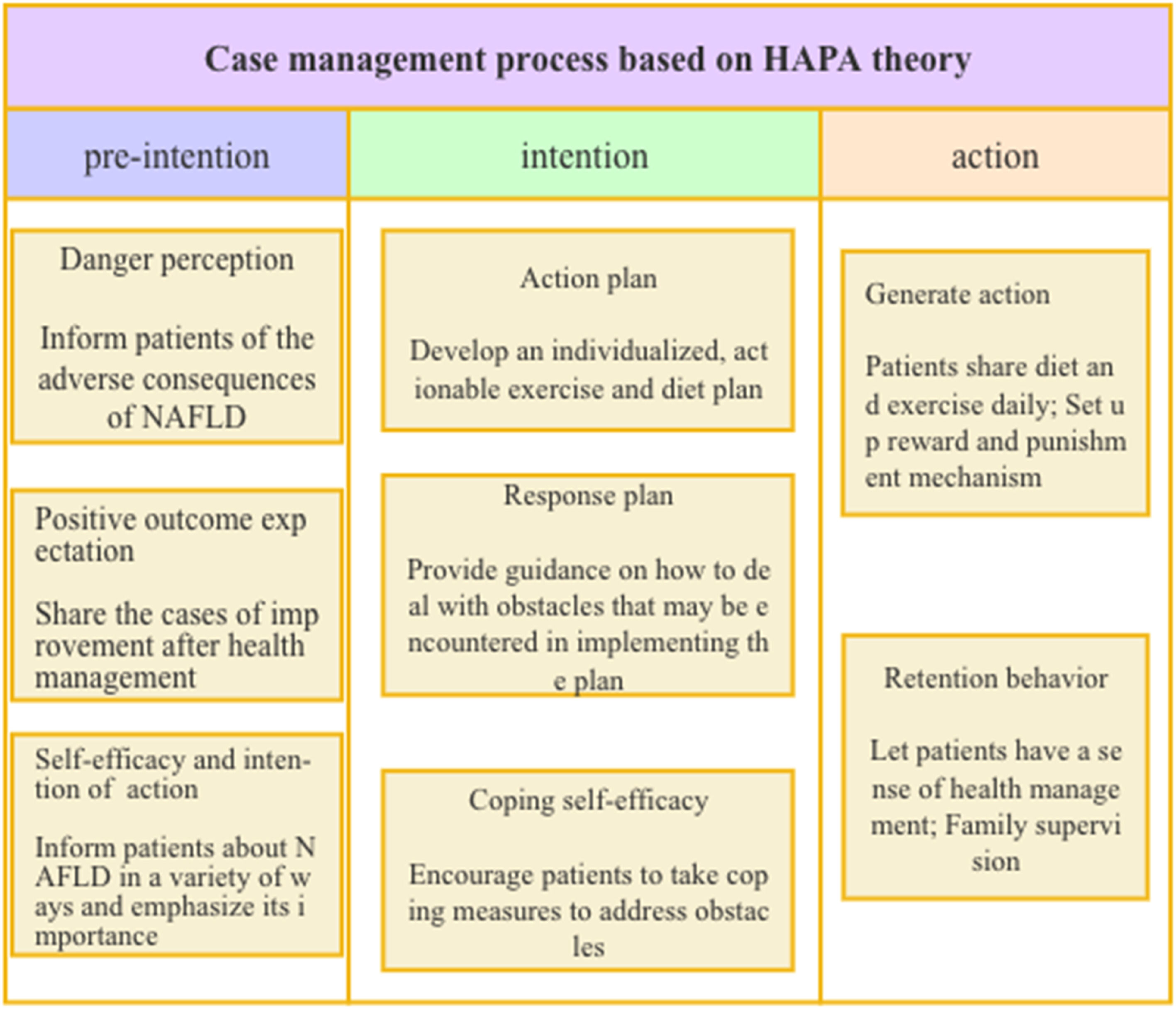

Traditional health education strategies primarily focus on providing patients with theoretical knowledge, rather than assisting efforts to modify or correct unhealthy habits [11]. In 1988, the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) approach was developed by Schwarzer, a German psychologist who sought to improve the conversion of behavioral intentions into outward behaviors [12]. The HAPA theory separates the development of healthy behaviors into volitional and motivational stages, with the emphasis on the creation of intention and the latter focusing on behavioral modification. Schwarzer also suggested that altering health-related behaviors is a continual process that progresses through the pre-intention, intention, and action stages. In recent years, this theory has been applied to elderly hypertension patients [13], type 2 diabetes patients [14], middle-aged and young stroke hemorrhagic patients [15] and asthma patients[16], etc., all of which show that health management based on this theory can effectively improve patients' compliance and self-management ability, thereby improving patients' quality of life.

Case management is a medical management approach that centers on patient health, to improve the quality of life and overall health of patients, optimizing and unifying fragmented healthcare efforts so as to provide patients with more comprehensive, continuous, and efficient medical care [17]. The case management model integrates evaluation, planning, implementation, coordination and evaluation, it optimizes and integrates traditional fragmented health care to ensure continuous, complete, and effective health care for patients.

In the present study, the HAPA theory was used to guide the development and implementation of MASLD patient case management, aiming to increase risk perception among MASLD patients and to help them develop positive outcome expectations, formulate personalized action plans and coping strategies to encourage action development and maintain these healthy habits in the long-term. This study explores whether these factors may play a role in promoting the formation and maintenance of healthy behaviors in patients with MASLD.

2Materials and Methods2.1Patient selectionThis study enrolled 228 patients meeting the MASLD diagnostic criteria from the Physical Examination Center of Jiangnan District of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University between January 1, 2023, and April 1, 2023, using a convenience sampling approach. Patient outcomes were evaluated following defined health management interventions based on ultrasound results (decreased hepatic near-field echo, decreased far-field echo attenuation, and improved hepatic vessel clarity). The study sample size was selected according to the following equation: n1=n2=(Uα+Uβ)2(1+1)/k(1−p)/P(P1,P2)2,P=(P1+P2)/2,k=1,α=0.05,Uα=1.960,β=0.200,Uβ=0.842. Based on prior references [18], it was determined that P1 = 80.83 % and P2 = 62.50 %. Based on an expected 20 % drop-out rate, 114 participants per group were selected for this study. Opaque envelopes containing cards with the Arabic numerals 1–228 were prepared to groups at random, with 1–114 corresponding to the control group and 15–228 corresponding to the experimental group. Group status was determined for patients meeting the defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. After the conclusion of the study, all data from patients who dropped out or were lost to follow-up were excluded, leaving a total of 102 patients per group. The patient selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

2.2Inclusion and exclusion criteriaTo be eligible for study inclusion, patients had to: (1) meet the NAFLD diagnostic criteria established in the Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Primary Care and Endocrinology [19], (2) be between the ages of 18 and 60, (3) have no neurological disorder and be capable of communicating and cooperating with researchers, (4) be capable of reading and able to use WeChat, sports bracelets, and other electronic devices, and (5) voluntarily agree to study participation and provide written informed consent.

Patients were excluded if they exhibited: (1) any motor system injuries or movement contraindications, (2) any diseases of the brain, heart, lungs, or other vital organs, (3) diseases that would affect the implementation of proscribed diets, or (4) the use of blood lipid or enzyme lowering drugs during the study.

2.2.1Control group interventionsPatients in the control group were provided with diet and exercise regimens. They and their families were educated about the disease, and classic cases were disseminated through WeChat groups, lectures, public tweets on WeChat, and other means. Dietitians and sports physicians collaborated to produce the mean plans and exercise regimens for these patients. They also provided education regarding food substitution, selection of appropriate exercise regimens, and the use of sports bracelets. A WeChat communication group was established to collect and compile weekly feedback on patients' medical histories related to diet and exercise.

2.2.2Experimental group interventionsPatients in the experimental group underwent three stages of health behaviour modification based on HAPA theory. First, a health management team for MASLD was established, composed of six nurses from the health management center, two doctors, a psychological counselor, and the head nurse of the facility. The two doctors were responsible for evaluating the physical and liver conditions of the patients, while the nurses handled implementation, follow-up, and data collection, with the head nurse overseeing and summarizing activities. Before the study began, the team members were required to have a comprehensive knowledge of MASLD health management and three stages of health behaviour generation (pre-intention, intention, and action), and how to apply HAPA theory in clinical practice.

The pre-intention phase of the intervention involved efforts to improve risk perception by helping patients better recognize the potential negative effects of MASLD using standard cases, presentation slides, films, and other materials. Simultaneously, result expectations were improved by regularly sharing examples of improved health management on a regular basis in a WeChat group, thereby boosting participant’ confidence and optimism regarding their treatment. Lastly, this phase also involved enhancing self-efficacy and purpose of action by providing patients with information regarding MASLD through WeChat groups, public tweets, communications with study nurses, and the implementation of diet and exercise regimens. In addition, patients' families were provided with the emotional support needed and relevant information necessary for MASLD management.

In the intention stage, patients were directed to use an action plan. Dietitians worked with patients and their families to develop individualized diet plans according to the specific conditions, diet, and lifestyle habits of the patients, guiding their food selection, and cooperating with family members for supervision. Patients and sports medicine doctors formulated an exercise plan based on the physical fitness and endurance of each patient. These nurses also helped patients to understand how to appropriately use exercise bracelets, monitored exercise frequencies and intensities, and summarized their exercise regimens weekly in the WeChat group to ensure that patients were aware of their current exercise status. A coping plan was also established by discussing the plan and any possible roadblocks with patients and their families as the plan is implemented, providing tailored coping strategies including teaching patients about alternative food substitution strategies, setting a daily alarm for a defined amount of exercise, and offering various exercise options. To promote coping self-efficacy, patients were informed that a skilled medical team was available to guide them throughout the procedure and that they could contact the responsible nurse at any time with any questions they may have. Patients were also encouraged to actively engage in corrective action at any time when the plan was not being carried out as intended, improving their understanding of self-management. In the process of intervention, nurses regularly communicated with patients to be aware of any changes in their psychological state and provided timely encouragement and enlightenment.

In the action phase, to help patients develop healthy behaviors, food diaries were shared on WeChat groups daily, allowing supervision of everyone's diet, while reporting their exercise performance weekly in the WeChat group. A reward system was implemented to encourage excellent work, prompt communication with patients exhibiting low compliance, and problem-solving. To promote the maintenance of established behaviours, efforts were made to aid patients in using different plates and consuming appropriate nutrients in moderation at each meal. Patients were also encouraged to habitually track their caloric intake, make cards with their diet plan for easy reference, work with family members in monitoring their mobility, and help patients recognize the advantages of health management to maintain behaviour modification (Fig. 2).

2.3Outcome indicatorsAfter a 6-month monitoring period, all participants underwent an additional health assessment to assess a series of outcome indicators.

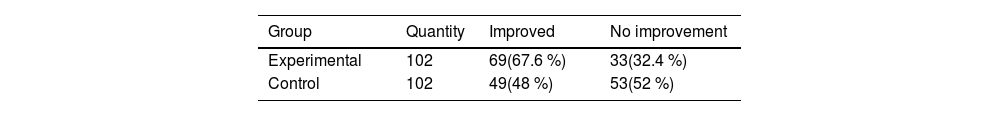

2.3.1Analyses of fatty liver improvementThe same physician used the GE LOGIQ-E9 real-time ultrasonic imaging instrument to assess fatty liver status in all patients before and after the intervention. Mild fatty liver was defined by the absence of hepatic enlargement, with uniform liver size and density, normal echo, and normal parenchymal echo. Moderate fatty liver was defined by a reduction in size, noticeable liver parenchymal thickening, a reduction in the liver parenchymal echo, and moderate to moderately high liver fat levels. Severe fatty liver was defined by high fat levels, visible thickening of the liver parenchyma, size reductions, and a visibly weaker parenchymal echo. If patients exhibited improvements in their prognosis from severe to moderate/mild/normal, moderate to mild/normal, or mild to normal, they were classified as improving, whereas all patients without any apparent improvement were classified as exhibiting no improvement.

2.3.2Body mass index and biochemical indicesAn identical Omron HNH-318 physical examination scale was used to determine the weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) of each patient before and after the intervention. The waist and hip circumferences of the patients were measured using the same soft measuring tape and the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was calculated. Fasting venous blood samples were collected from these patients and used to measure total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels.

2.3.3Analyses of health behavioursThe HPLP-II health promotion lifestyle scale was used to evaluate health-related behaviours before and after the intervention for patients in this study, assessing six different health behaviour dimensions (physical exercise, health responsibility, stress management, nutrition, interpersonal relationships, and spiritual growth) [20]. The maximum possible score of 240 corresponds to the possible health behaviours.

2.4Statistical analysesData were analysed using SPSS 26.0 Continuous data were reported as means ±s and compared with Student's t-tests, while categorical data were reported as numbers (%) and compared with χ2-tests. Graded data were compared with Z-tests. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

2.5Ethical statementsWritten informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study and the study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (registered at the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ChiCTR2400086407) and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

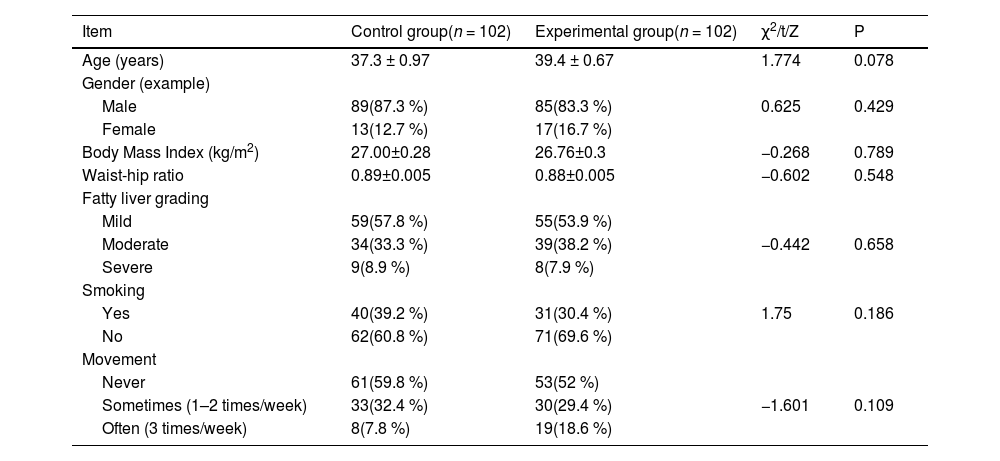

3Results3.1Baseline patient characteristics and analyses of fatty liver severity pre- and post-interventionComparable baseline data showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (Table 1). After the intervention, the improvement in fatty liver condition in the experimental group was significantly better than that in the control group. (P < 0.01) (Table 2).

Comparison of baseline data between NAFLD patients in the control and experimental groups.

| Item | Control group(n = 102) | Experimental group(n = 102) | χ2/t/Z | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.3 ± 0.97 | 39.4 ± 0.67 | 1.774 | 0.078 |

| Gender (example) | ||||

| Male | 89(87.3 %) | 85(83.3 %) | 0.625 | 0.429 |

| Female | 13(12.7 %) | 17(16.7 %) | ||

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 27.00±0.28 | 26.76±0.3 | −0.268 | 0.789 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.89±0.005 | 0.88±0.005 | −0.602 | 0.548 |

| Fatty liver grading | ||||

| Mild | 59(57.8 %) | 55(53.9 %) | ||

| Moderate | 34(33.3 %) | 39(38.2 %) | −0.442 | 0.658 |

| Severe | 9(8.9 %) | 8(7.9 %) | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 40(39.2 %) | 31(30.4 %) | 1.75 | 0.186 |

| No | 62(60.8 %) | 71(69.6 %) | ||

| Movement | ||||

| Never | 61(59.8 %) | 53(52 %) | ||

| Sometimes (1–2 times/week) | 33(32.4 %) | 30(29.4 %) | −1.601 | 0.109 |

| Often (3 times/week) | 8(7.8 %) | 19(18.6 %) | ||

Prior to the intervention, no significant differences in BMI values or biochemical indices were observed between groups (P > 0.05). Following the intervention, all biochemical indices, except for TG, (P < 0.05) and BMI values in the experimental group were significantly lower than those in the control group (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Comparison of BMI, WHR, and biochemical indexes before and after interventions in the control and experimental groups (x ± s).

| Item | Experimental group(n = 102) | Control group (n = 102) | 2 groups before intervention | 2 groups after intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | T1 | P1 | T2 | P2 | |

| TC | 5.47±0.11 | 4.38±0.1① | 5.52±0.11 | 5.15±0.1② | −0.34 | 0.734 | −5.125 | <0.001 |

| HDLC | 1.19±0.03 | 1.45±0.01① | 1.16±0.02 | 1.28±0.02② | 0.798 | 0.426 | 9.867 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C | 2.99±0.08 | 2.47±0.08① | 3.12±0.08 | 2.85±0.07② | −1.145 | 0.253 | −3.633 | <0.001 |

| TG | 2.5 ± 0.14 | 1.78±0.1① | 2.48±0.14 | 2.07±0.11② | 0.125 | 0.901 | −2.02 | <0.05 |

| ALT | 38.4 ± 2.11 | 25.67±2.01① | 44.27±2.79 | 37.69±2.75③ | −1.668 | 0.097 | −3.528 | <0.001 |

| AST | 26.3 ± 0.95 | 18.35±0.94① | 28.36±1.05 | 23.8 ± 1.08② | −1.437 | 0.152 | −3.827 | <0.001 |

| BMI | 27.0 ± 0.28 | 23.57±0.25① | 26.76±0.3 | 25.52±0.24② | 0.268 | 0.789 | −5.555 | <0.001 |

| WHR | 0.88±0.01 | 0.80±0006① | 0.89±0.005 | 0.86±0.005② | −0.602 | 0.548 | −8.027 | <0.001 |

Note: Pre-intervention vs. post-intervention values in the experimental group, ①P < 0.001; Pre-intervention vs. post-intervention values in the control group, ②P < 0.05, ③P > 0.05. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

There were no significant differences in the health behaviour scores between the two groups before intervention. (P > 0.05). After the interventional period, the scores in the experimental group were significantly higher than those in the control group for all dimensions (P < 0.05), except for interpersonal relationships. (P > 0.05) (Table 4).

Comparisons of scores for different HPLP-II2 dimensions between groups before and after intervention (x ± s).

| Item | Experimental group(n = 102) | Control group(n = 102) | 2 groups before intervention | 2 groups after intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | T1 | P1 | T2 | P2 | |

| Sense of health | 21.1 ± 0.21 | 26.2 ± 0.37① | 20.6 ± 0.17 | 23.3 ± 0.15② | 1.721 | 0.087 | 7.037 | <0.001 |

| Exercise | 19.8 ± 0.23 | 26.4 ± 0.17① | 19.9 ± 0.24 | 22.2 ± 0.2② | −0.364 | 0.716 | 15.967 | <0.001 |

| Nourishment | 20.4 ± 0.23 | 27.1 ± 0.3① | 20.2 ± 0.28 | 22.5 ± 0.23② | 0.575 | 0.566 | 12.153 | <0.001 |

| Self-actualization | 19.95±0.13 | 23.9 ± 0.3① | 20.3 ± 0.22 | 23.2 ± 0.19② | −1.447 | 0.15 | 2.076 | <0.05 |

| Interpersonal relationship nnjklnn | 21.25±0.24 | 26.4 ± 0.3① | 21.9 ± 0.27 | 25.9 ± 0.2② | −1.665 | 0.098 | 1.443 | >0.05 |

| Stress management | 22.7 ± 0.19 | 29.0 ± 0.2① | 22.8 ± 0.27 | 25.5 ± 0.23② | −0.118 | 0.906 | 11.699 | <0.001 |

Note: All groups were compared to the same group before intervention. ① ②p < 0.05.

BMI>23, increased waist circumference, dyslipidemia, and hyperglycemia are the main cardiovascular risk factors in patients with MASLD [21]. Developing a healthy diet and maintaining long-term exercise are the basis for the treatment of MASLD. By reducing the intake of calories through diet and promoting lipid metabolism alongside increasing energy consumption through conjunction with exercise, an effective combination of diet and exercise can achieve slow weight reduction while avoiding further liver damage caused by uncontrolled weight loss [22,23]. The results of this study showed that the improvement of liver function in the experimental group was better than that in the control group, consistent with Liu Rongzhi's results [24]. Based on the case management under HAPA theory, firstly, by making patients fully understand the harm of continuous development of MASLD and the effectiveness of persistent management, patients can make behavior change intention. Secondly, different from the traditional preaching mode, the program uses physical fitness technology to customize individualized and effective exercise methods for patients. Dietitians work with patients to formulate a diet plan that meets their personal tastes according to their eating habits and list potential problems and coping plans during the implementation of the plan, effectively improving patients' action intentions and self-coping effectiveness. In addition, using WeChat group check-ins and family members participation in the supervision, reasons for low compliance, plans are adjusted, and patient compliance to the program is enhanced, promoting active participate in self-management, and ultimately improving liver function.

The results also revealed that after the intervention period, the HDL-C levels of individuals in the experimental group were significantly higher compared to the control group, with corresponding reductions in BMI, body fat percentage, TC, TG, LDL-C, AST, and ALT values, which was similar to the results of Montemayor S et al. [23]. The pathophysiology of MASLD is generally thought to be explained by a “two-hit” model wherein impaired lipid metabolism leads to hepatic lipid accumulation, in turn contributing to insulin resistance. This results in the induction of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokine release, leading to steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and other adverse outcomes [25]. The application of an appropriate individualized dietary plan focused on regulating free fatty acid intake and absorption can help facilitate weight loss and reduce insulin resistance, and decrease excessive lipids in the liver, improving fatty liver symptoms. Frequent aerobic exercise can improve glucose utilization, reduce fat transformation, and increase fat utilization [26]. Studies have also reported a 10 % reduction in TG levels in patients who took part in weight training for an 8-week period [27]. Therefore, timely and effective health intervention can significantly reduce liver fat, alleviate liver damage, and improve disease prognosis [24]. Case management based on HAPA theory can effectively translates the intention into action. It use of effective health education and the formulation of response plans ensures the execution of the diet and exercise plan of the patients. At the same time, supervision and guidance are implemented during the action stage to ensure the effectiveness of the dietary and exercise interventions, thus improving both liver function and lipid metabolism.

Although there is some improvement in MASLD through weight loss, only 30 % of MASLD participants can achieve weight loss through lifestyle changes. And simple didactic health education is often ineffective [28]. According to HAPA theory [29], the development of individual health behaviors is a complex process affected by a series of cognitive psychological factors from behavioral motivation to the external performance of behaviors. Behaviors change processes through different stages, with individuals facing different tasks or problems at each stage. By comprehensively assessing the factors affecting the behavioral stage and psychological state of the patient, the implementation of case management can also be dynamically adjusted and corrected according to the behavioral change stage of the patient to facilitate the formation of the patient's healthy behavior. The results of this study show that the scores of health responsibility, exercise, nutrition, and stress management in the experimental group were higher than those in the control group (p < 0.05). This indicates that case management based on the HAPA theory has a positive effect on the development of health behaviors in MASLD patients, which is consistent with the results obtained after the management of chronic heart failure patients [30] and elderly hypertension patients [13] based on this theory. Conventional health education strategies focus on the prevalence of MASLD and lack specificity for individual patients, disregarding the journey of a given patient from intention to actual behavioural changes. Poor lifestyle choices can be challenging for MASLD patients to overcome, and there is also a lack of risk perception and outcome expectation of the disease. Simply providing patients with basic health education is thus unlikely to yield the desired results [28].

The process of behavior change under HAPA theory is divided into pre-intention stage, intention stage and the action stage. In the pre-intention stage, patient awareness of risks is increased, highlighting negative illness-related effects. By sharing success stories, efforts are made to motivate patients to transition to a better health stage and to be more optimistic regarding their potential personal outcomes. However, good behavioral intention does not necessarily lead to healthy behavior [31]. Therefore, as an intermediary variable, planning fills the gap from behavioral intention to healthy behavior and can promote the effective transformation from behavioral intention to healthy behavior. To facilitate the transition from the intention to action phases, a customized exercise program and dietary guidelines taking the unique circumstances of each patient into account were developed in consultation with the patient and qualified medical professionals. Planning also includes action and coping plans, the advantage of coping plans is that patients plan coping strategies for possible emergencies, thus improving the compliance of patients in implementing the plan. The goal of the action stage is to track the development of health behaviours for patients and to provide motivation for the adoption of self-coping strategies that can help support the long-term maintenance of health behaviors [29]. Case management under HAPA theory provides individualized and targeted guidance at different stages, which promotes the development of patients' healthy behaviors and makes patients get the maximum benefit.

Due to time and manpower constraints, the subjects of this study were only patients undergoing physical examination in the Health Medical Center of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, and the sample source was relatively single, which could not represent the health behavior and fatty liver improvement of the overall MASLD patients in China. It is suggested that the sample size should be expanded and multi-center and cross-regional interventions should be carried out in future research.

5ConclusionsHAPA theory-based case management efforts can provide benefits to MASLD patients, contributing to improvements in liver function, body shape, and lipid metabolism. Importantly, this strategy can aid patients in their efforts to establish and maintain healthy behaviours, thus it is worthy of promotion in the clinic.

Author contributionsMei Jia: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; statistical analysis; study design. Chen Ying: study concept; study supervision; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Xie Yuncai: study design; acquisition of data. Huang Pingping, Jin Yudi, Wang Xia: acquisition of data.

FundingChina Social Welfare Foundation (HLCXKT-20,230,137).

Thanks to all participants for their support.