Studies evaluating urine culture requests in our country have highlighted a high rate of requests that fall outside the indications specified in clinical guidelines. We evaluated the current degree of inadequacy in the request of urine cultures and how this influences the therapeutic decisions of general practitioners.

DesignCross-sectional descriptive study.

SettingThree primary care centres in Tarragona area.

ParticipantsUrine culture requests from the adult population≥18 years old, received at the Microbiology Service of the reference hospital in 2022. All requests were made in primary care settings.

Main measuresThe collected variables included sociodemographic data, urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms at the time of the urine culture request, comorbidities, reason for the request (including diagnosis), type of urine culture, therapeutic approach before and after receiving the result, and the urine culture result.

ResultsA total of 461 urine cultures were reviewed: 152 men (mean age 64.1 years) and 309 women (mean age 57 years). Of the urine cultures analyzed, 17.4% were for cystitis (22% in women), 2.4% for pyelonephritis, 1.3% for complicated UTIs, and 1.5% for asymptomatic bacteriuria. In 10.6%, they were for recurrent UTIs; in 9.6%, post-treatment. In 55.5% of cases, general practitioners continued without antibiotic treatment, regardless of urine culture results. The reason to request was unknown in 18.9%. Antibiotic changes occurred in 5.6%.

ConclusionsThere is still a high rate of urine culture over-requesting in primary care, with 20% of cultures being ordered for otherwise uncomplicated UTIs. While the methodology of the project does not allow for causal analysis, it provides a detailed description of clinical practices in primary care.

Los estudios dirigidos a evaluar las solicitudes de urocultivos en nuestro país han puesto de manifiesto una alta tasa de solicitudes de urocultivos fuera de las indicaciones de las guías clínicas. Evaluamos el grado actual de inadecuación y cómo esto influye en la decisión terapéutica de los médicos de familia.

DiseñoEstudio descriptivo transversal.

EmplazamientoTres centros de salud en Tarragona.

ParticipantesPeticiones de urocultivos de población adulta ≥18años recibidas en el Servicio de Microbiología del hospital de referencia en 2022. Todas las solicitudes se pidieron en atención primaria.

Mediciones principalesLas variables incluyeron datos sociodemográficos, síntomas de infección del tracto urinario (ITU) en el momento de su petición, comorbilidades, motivo (incluido el diagnóstico), tipo de urocultivo, manejo terapéutico antes y después de recibir el resultado y el resultado del urocultivo.

ResultadosSe revisaron 461 urocultivos: 152 hombres (edad media 64,1años) y 309 mujeres (edad media 57años). De los urocultivos analizados, el 17,4% fueron por cistitis (22% en mujeres), el 2,4% por pielonefritis, el 1,3% por ITU complicadas y el 1,5% por bacteriuria asintomática. En el 10,6% fueron por ITU recurrentes; en el 9,6%, post-tratamiento. En el 55,5% de los casos, los médicos continuaron sin tratamiento antibiótico, independientemente de los resultados de los urocultivos. El motivo para pedir urocultivos fue desconocido en el 18,9%. Los cambios en el tratamiento antibiótico se observaron en el 5,6%.

ConclusionesTodavía hay una alta tasa de solicitud de urocultivos en atención primaria, con un 20% de los cultivos solicitados para infecciones urinarias no complicadas. La metodología del proyecto no permite un análisis causal, pero sí una descripción de la práctica clínica en atención primaria.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most prevalent bacterial infections encountered in both community and health care settings, contributing significantly to administration of antibiotics in medical practice.1,2 Between 20 and 30% of women will experience a UTI during their lifetime, and of these, 20–40% will have a recurrence. In the elderly, the prevalence can reach 20–50%.3 UTIs exhibit a wide spectrum of heterogeneity in terms of their underlying causes, clinical manifestations, and disease progression, ranging from relatively benign cases with mild symptoms (cystitis) to severe and potentially life-threatening conditions (such as pyelonephritis, bacteraemia, and septic shock).4

Until two decades ago, international and local protocols for managing patients with UTI symptoms generally included performing pre- and post-treatment cultures.5,6 Currently, the approach to follow-up in these patients has changed significantly. Routine identification of the causal agent is not considered necessary, especially in cases of uncomplicated cystitis, which is defined as acute, sporadic, or recurrent cystitis limited to nonpregnant women with no known relevant anatomic or functional abnormalities in the urinary tract and no comorbidities.7,8

Nowadays, it is possible to access a list of the microorganisms that most frequently cause UTIs, as well as the antibiotics to which they are most susceptible. Thus, in daily practice, general practitioners are often able to prescribe empirical treatment without the need for a prior urine culture. However, post-treatment urine cultures are still requested. In recent years, various authors have debated the usefulness of performing this follow-up in all cases, especially in uncomplicated infections where symptoms do not persist after treatment. According to the 2024 guidelines of the European Association of Urology, a urine culture is recommended in the following situations: (a) suspected acute pyelonephritis; (b) symptoms that do not resolve or recur within 4 weeks after completion of treatment; (c) women who present with atypical symptoms; (d) pregnant women; (e) women whose symptoms do not resolve by the end of treatment, and (f) those whose symptoms resolve but recur within 2 weeks. Routine post-treatment urinalysis or urine culture are not indicated for asymptomatic patients.8 In case of men, the guidelines consider the UTI as complicated UTI and in all these cases a urine culture should be performed.8

Regarding the inappropriateness in the request for urine cultures, different studies carried out in Spain have reported percentages ranging from 14% to 33% before the treatment is administered.9–11 Piñero et al.9 found that 44% of the requests made by general practitioners in Toledo were made in cases of asymptomatic bacteriuria, where it would not be necessary to request or treat them. In a more recent study performed in Barcelona, the percentage of inappropriateness in uncomplicated cystitis was 32%, indicating a high over-requesting.12 However, regarding the request for urine cultures for recurrent cystitis, this percentage was only 49%, indicating under-requesting. Notwithstanding, the request of post-treatment urine culture is even more inappropriate. In 2014, 92% of urine cultures requested for a second time in a UTI were unnecessary.10

We aim to understand to what extent urine culture requests from primary care influence the therapeutic decisions of professionals and whether any associated factors affect these changes. Various studies indicate that requesting a urine culture result in a change in antibiotic treatment in 10–15% of cases.9,11 The main objective is to assess the degree of inadequacy in urine culture requests based on local clinical practice guidelines, how these requests influence the therapeutic decisions of general practitioners, and to establish a foundation for a training intervention.

Material and methodsCross-sectional descriptive study of the urine culture requests from the adult population≥18 years old, received at the Microbiology Service of Joan XXIII Hospital in Tarragona during 2022. All requests were made in primary care settings. Several health centres in the Tarragona area (Catalonia) were selected, with Joan XXIII Hospital serving as the reference hospital. The centres were chosen based on convenience, aiming to represent both urban and rural populations. A total of three health centres participated: Jaume I (located in the city of Tarragona, assigned population of 27,000 citizens, 19 general practitioners and 21 nurses), Tarraco (in Tarragona too, population of 15,000 citizens, 11 general practitioners and 12 nurses), and Morell (situated in a rural area, an assigned population of 12,000 citizens, 7 general practitioners and 10 nurses).

We excluded urine cultures in which no patient medical record was found, and those where, despite having a record, there was no information regarding the clinical episode and/or the therapeutic approach taken. We also excluded cases that were part of a concurrently running randomized clinical trial called SCOUT, conducted at one of the centres.

The variables collected were sociodemographic data, UTI symptoms at the time of the urine culture request, associated comorbidities and underlying conditions, reason why this urine culture was requested for, including the diagnoses such as recurrent UTIs, urine culture result, and therapeutic approach after receiving the urine culture result (Supplementary Table 1). Closed-ended questions were prioritized to minimize confusion. The degree of inappropriateness of urine culture requests was determined according to local clinical practice guidelines.8 Study data were collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools, hosted at Fundació Institut Universitari per a la recerca a l’Atenció Primària de Salut Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAPJGol).11,12 REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing (a) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; (b) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (c) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (d) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.13,14

Potential candidates were pre-selected using data extracted from SIDIAP (Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care).15 The SIDIAP contains pseudonymized clinical information from the Electronic Health Records in Primary Care (Estació Clínica d’Atenció Primària) programme, which is the electronic health record programme for primary healthcare of the Catalan Health Institute (Institut Català de la Salut) in Catalonia. A list of selected patients was generated and made available at each practitioner's clinical station for chart review in the order of the list.

Statistical analysisThe sample size was calculated for an alpha error of 0.05, power of 80% and inadequacy of 50%, considering the total amount of urine cultures of approximately 200,000 processed at the Department of Microbiology in 2021, with a total of 384 medical records to be reviewed. At the end we could review 461 urine cultures.

Descriptive statistics of the observed results was carried out, using frequencies (percentages) for the categorical variables and means (and standard deviations) for quantitative variables. The data were analyzed using the R statistical programme, using Fisher exact test to the frequencies and Student's t-test to compare quantitative variables. Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05.

ResultsA total of 461 urine cultures were reviewed, involving 152 men and 309 women, with 18.1% of the women being pregnant. The mean age of the men was 64.1 years (SD 15.8 years), while the mean age of the women was 57 years (SD 20.2 years; p<0.001). The most common symptom leading to a urine culture request was dysuria (painful urination), occurring in 18.4% of men and 37.9% of women (p<0.001), followed by increased urinary frequency (17.8% of men and 18.1% of women). However, 41.9% of patients had no recorded symptoms (Table 1). The most frequent diagnosis for which a urine culture was requested in women was cystitis (22.0%), followed by pregnancy (18.1%), whereas in men was due to abnormalities and/or renal failure (33.6%) (Table 1). Among men, benign prostatic hyperplasia (34.2%) was the most common comorbidity, while in women, it was a previous history of cystitis (18.4%).

Main characteristics of the subjects of the study.

| Overall(n=461) | Men(n=152) | Women(n=309) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 59.3 (19.1) | 64.1 (15.8) | 57 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy | 56 (18.6) | 0 (0) | 56 (18.1) | |

| Symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Dysuria | 145 (31.5) | 28 (18.4) | 117 (37.9) | <0.001 |

| Frequency | 83 (18.0) | 27 (17.8) | 56 (18.1) | 1 |

| Urgency | 56 (12.1) | 18 (11.8) | 38 (12.3) | 1 |

| Tenesmus | 47 (10.2) | 15 (9.9) | 32 (10.4) | 1 |

| Haematuria | 39 (8.5) | 18 (11.8) | 21 (6.8) | 0.1 |

| Suprapubic pain | 35 (7.6) | 8 (5.3) | 27 (8.7) | 0.25 |

| Lower back pain | 26 (5.6) | 6 (3.9) | 20 (6.5) | 0.37 |

| Discomfort | 19 (4.1) | 4 (2.6) | 15 (4.9) | 0.38 |

| Fever | 14 (3.0) | 9 (5.9) | 5 (1.6) | 0.02 |

| None of the above | 193 (41.9) | 71 (46.7) | 122 (39.5) | 0.17 |

| Underlying conditions, n (%) | ||||

| Previous cystitis | 66 (14.3) | 9 (5.9) | 57 (18.4) | 0.001 |

| Urinary incontinence | 64 (13.9) | 17 (11.2) | 47 (15.2) | 0.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 61 (13.2) | 26 (17.1) | 35 (11.3) | 0.11 |

| Menopause | 55 (11.9) | 0 (0.0) | 55 (17.8) | NA |

| Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 52 (11.3) | 52 (34.2) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Renal lithiasis | 39 (8.5) | 18 (11.8) | 21 (6.8) | 0.1 |

| Immunological disease | 33 (7.2) | 17 (11.2) | 16 (5.2) | 0.03 |

| Cystocele | 15 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 15 (4.9) | 0.01 |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | 6 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 4 (1.3) | 1 |

| Kidney transplant | 5 (1.1) | 4 (2.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0.08 |

| Urinary catheter | 5 (1.1) | 5 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Gynaecological surgery | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.0) | NA |

| None of the above | 184 (39.9) | 40 (26.3) | 144 (46.6) | <0.001 |

NA=not available.

Of all the urine cultures analyzed, 17.4% were attributable to cystitis episodes, with a higher rate in women compared to men (22 vs. 7.9%; p<0.001). Cases of pyelonephritis, complicated UTIs, and asymptomatic bacteriuria accounted for 2.4%, 1.3%, and 1.5% of all the urine cultures ordered, respectively. In 10.6% of all cases, urine cultures were requested for recurrent UTIs, while in 9.6% of cases, they were ordered after UTI treatment (11.6% in women). Therapeutic failure accounted for 3.5% of the urine cultures requested, and in 18.9% of cases, the reason for registering the urine culture request was unknown (Table 2).

Reason why a urine culture was requested.a

| Overall | Men | Women | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cystitis, n (%) | 80 (17.4) | 12 (7.9) | 68 (22.0) | <0.001 |

| Pyelonephritis, n (%) | 11 (2.4) | 2 (1.3) | 9 (2.9) | 0.46 |

| Complicated UTI, n (%) | 6 (1.3) | 5 (3.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0.03 |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria, n (%) | 7 (1.5) | 2 (1.3) | 5 (1.6) | 1 |

| Recurrent UTI, n (%) | 49 (10.6) | 11 (7.2) | 38 (12.3) | 0.13 |

| Post-treatment of a UTI, n (%) | 39 (8.5) | 8 (5.3) | 31 (10.0) | 0.12 |

| Therapeutic failure (%) | 16 (3.5) | 1 (0.7) | 15 (4.9) | 0.04 |

| Abnormalities or renal failureb, n (%) | 85 (18.4) | 51 (33.6) | 34 (11.0) | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy, n (%) | 56 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 56 (18.1) | NA |

| Haematuria, n (%) | 19 (4.1) | 8 (5.3) | 11 (3.6) | 0.54 |

| Others, n (%) | 34 (7.4) | 14 (9.2) | 20 (6.5) | 0.38 |

| Unknown, n (%) | 87 (18.9) | 39 (25.7) | 48 (15.5) | 0.01 |

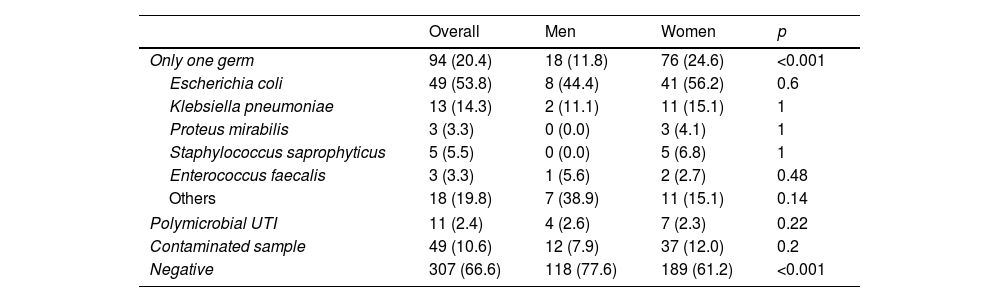

In most cases, general practitioners did not change their decision depending on the results of the cultures as they continued without antibiotic treatment in 55.5% of the cases. In 17.6% there was no change in antibiotic treatment (Table 3). A change in the antibiotic treatment was observed in 5.6% of the cases. The urine culture results were negative in 66.6% of cases, with a higher rate in men compared to women (77.6% vs. 61.2%, p<0.001) (Table 4). The germ most frequently isolated in both men and women was Escherichia coli, accounting for 53.8% of the cultures (Table 4).

Decision taken by the general practitioner when reading the urine culture result.

| Overall | Men | Women | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continues without antibiotic therapy | 256 (55.5) | 98 (64.5) | 158 (51.1) | 0.01 |

| Start antibiotic treatment | 26 (5.6) | 3 (2.0) | 23 (7.4) | 0.03 |

| No change in antibiotic treatment | 81 (17.6) | 20 (13.2) | 61 (19.7) | 0.11 |

| Finish antibiotic treatment | 15 (3.3) | 7 (4.6) | 8 (2.6) | 0.38 |

| Change in antibiotic treatment | 26 (5.6) | 7 (4.6) | 19 (6.1) | 0.64 |

| Other decisions taken | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (1.7) | 0.68 |

| Not reported | 51 (11.1) | 16 (10.5) | 35 (11.4) | 0.92 |

| Total | 461 (100.0) | 152 (100.0) | 309 (100.0) | |

Urine cultures results.

| Overall | Men | Women | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only one germ | 94 (20.4) | 18 (11.8) | 76 (24.6) | <0.001 |

| Escherichia coli | 49 (53.8) | 8 (44.4) | 41 (56.2) | 0.6 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 13 (14.3) | 2 (11.1) | 11 (15.1) | 1 |

| Proteus mirabilis | 3 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.1) | 1 |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | 5 (5.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (6.8) | 1 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 3 (3.3) | 1 (5.6) | 2 (2.7) | 0.48 |

| Others | 18 (19.8) | 7 (38.9) | 11 (15.1) | 0.14 |

| Polymicrobial UTI | 11 (2.4) | 4 (2.6) | 7 (2.3) | 0.22 |

| Contaminated sample | 49 (10.6) | 12 (7.9) | 37 (12.0) | 0.2 |

| Negative | 307 (66.6) | 118 (77.6) | 189 (61.2) | <0.001 |

The results of this study highlight a percentage of urine cultures that were requested by general practitioners without support from current recommendations, leading to unnecessary over-requesting. The distribution of gender, isolated pathogens, and associated risk factors observed in our study aligns with the literature, supporting the validity of our results. The high percentage of urine cultures from men – approximately one third of all the urine cultures requested – can be explained by the fact that most protocols recommend requesting cultures both before and after treatment in men, as these infections are considered complicated. In contrast, urine cultures in women are requested in certain specific situations, not always when a UTI is suspected, unlike in men, and their number is higher.

In our study, the number of urine cultures requested for asymptomatic bacteriuria was 1.5%, which is lower than in other studies and aligns with the guidelines, reflecting an improvement compared to previous results.9–12 However, the number of urine cultures requested for women with cystitis is 22%, like other studies, suggesting an over-requesting of cultures.9–12,16 Notably, the low number of urine culture requests for pyelonephritis, at 2.4%, and for complicated UTIs, only 1.3%, may indicate under-requesting. This could likely be explained by the fact that many of these patients are diagnosed and followed up at the hospital level rather than in primary care. In nearly 20% of the cases the reason for the urine culture request was unknown, suggesting low report by general practitioners, possibly due to the high demand for care and the lack of time for patient which makes recording difficult. A survey published in the last decade showed that urine cultures were requested by Spanish doctors for 26% of patients with uncomplicated UTIs.17

The issue of over- and under-requesting urine cultures is important in the management of UTIs, as it can have a significant impact on public health and on the quality of medical care.18 On one hand, the over-requesting of urine cultures in uncomplicated UTIs and bacteriuria can lead to the misuse of antibiotics. When tests that are not necessary are conducted, the risk of overtreatment increases, which not only incurs extra costs for the healthcare system but can also cause adverse effects in patients and contribute to increase antimicrobial resistance. Furthermore, the usual practice of requesting urine cultures in older individuals, who have often been exposed to multiple antibiotic treatments, it may result in antibiograms indicating the use of second-line antibiotics for multidrug-resistant pathogens, which further complicates the management of these infections. On the other hand, the suspected under-requesting of urine cultures in cases of complicated UTIs, as observed with recurrent UTIs in Barcelona in 2022, highlights a deficiency in detecting and properly treating these infections.12 Identifying the causal agent is crucial to ensure appropriate treatment, especially in patients with additional risk factors or more serious conditions.

Another key point of our study is that in 17.6% of cases, there was no change in the clinician's approach after receiving the urine culture results. According to the VINCat (Vigilància de les infeccions relacionades amb l’atenció sanitària a Catalunya) results in Tarragona, the antibiotic of choice for uncomplicated UTIs is fosfomycin, which shows 100% susceptibility against E. coli in our region.19 The empirical use of this antibiotic, along with its single-dose regimen, explains the high percentage of cases with no change in medication. Additionally, primary care doctors having access to local bacterial susceptibilities and resistances allows for more accurate treatment decisions.

Based on our study, we conclude that a significant number of urine cultures were requested inappropriately, according to clinical practice guidelines, while a notable percentage of cases showed over-requesting, as shown in other international studies. In cases of uncomplicated lower UTI, these tests should not be requested because of their cost, time and effort and the results of urine cultures do not imply a change in the treatment implemented. Before requesting any complementary test, it is essential to consider whether it is indicated. An important factor to assess is how the test result may influence our subsequent decision-making. Additionally, we highlight the importance of proper medical record-keeping. Although this can be challenging, particularly when demand for care is high, it is crucial to document the reason for consultation and the actions taken. This practice improves patient follow-up and facilitates better decision-making.

Limitations of the studyDescriptive studies are valuable for providing an overview of trends within a specific context; however, they do not permit the establishment of causal relationships or the drawing of robust conclusions. Therefore, any inferences derived from such findings should be made with caution. Additionally, the generalisability of the results is limited. Given the particular context in which the data were collected—including the sample population and a specific geographical setting—the findings may not be applicable to broader or more heterogeneous populations. As an observational study, this design does not allow for causal analysis, and potential confounding variables remain a concern, which is a well-known limitation of observational research. These factors must be considered when interpreting the study's results. Nevertheless, the study also has notable strengths. The study reflects clinical practice, capturing what general practitioners do in their daily work and how they decide when to request a urine culture. Furthermore, convenience sampling enabled the collection of the desired variables from the sample in a short amount of time, which is useful in exploratory research. It also allowed for the inclusion of both urban and rural healthcare settings within the same autonomous community, increasing the relevance of the study by incorporating different practice environments. Despite its limitations, the study provides valuable insights into current practices and potential areas for improvement in primary care.

ConclusionsA high rate of over-requesting urine cultures is still observed in primary care, with 20% of cultures being requested for otherwise uncomplicated UTIs. However, our study shows a positive trend regarding the request for asymptomatic bacteriuria, reflecting the increasing awareness among general practitioners about not treating this condition unless pregnancy is detected. The number of changes in antibiotic therapy initiated upon reviewing the results of the urine cultures is lower than that observed in previous studies, indicating that requests for cultures are still unnecessary in most cases.

- •

Different studies have previously shown a high percentage of both over-requesting urine cultures, mainly for asymptomatic bacteriuria and uncomplicated urinary tract infections, and under-requesting for complicated infections in primary care.

- •

Over-requesting cultures may lead to antibiotic overprescribing and contribute to the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

- •

The percentage of changes in prescribed antibiotics upon reading the urine cultures ranges from 10% to 15%.

- •

The percentage of over-requesting urine cultures remains high, with one-fifth of cultures ordered for uncomplicated UTIs.

- •

The requesting of urine cultures for asymptomatic bacteriuria has decreased in recent years.

- •

The results of the present study do not demonstrate substantial changes in antibiotic treatment following the receipt of urine culture results. However, further studies with more robust designs are needed to confirm this observation and explore the underlying reasons for this clinical practice.

The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, the Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and current legal regulations. Favourable approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicines of IDIAPJGol (reference: 23/151-P) on 27/09/2023.

All the information obtained in the study will be treated confidentially, in compliance with Organic Law on the Protection of Personal Data 3/2018, of December 5 and the Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of April 27, 2016, on Data Protection.

FundingThis research was funded by Strategic Research and Innovation Plan for Health (Pla Estratègic de Recerca i Innovació en Salut) 2022–2024 grant for the financing of research projects in the field of primary health care, grant number SLT021/21/000022.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.