We assessed the impact of the implementation of a simple multifaceted intervention aimed at improving management of cystitis in primary care.

DesignQuality control before and after study.

SitePrimary care centres in Barcelona city provided by the Catalonian Institute of Health.

ParticipantsThe multifaceted intervention consisted of (1) creation of a group with a leader in each of the primary care centres, out of hours services, sexual and reproductive centres, and home visit service, (2) session on management of cystitis in each centre, (3) result feedback for professionals, and (4) provision of infographics for professionals and patients with urinary tract infections. Interventions started in November 2020 and ended in the summer of 2021.

Main measurementsVariation in the prescription of first-line antibiotics, usage of antibiotics, and request for urine cultures before and after this intervention.

ResultsTraining sessions took place in 93% of the centres. The use of first-line therapies cystitis increased by 6.4% after the intervention (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.7–7.1%). The use of nitrofurantoin in recurrent cystitis increased, mainly in out of hours service (8.7%; 95% CI, 5.2–12.2%). Urine cultures were more frequently requested after the intervention for recurrent cystitis in both primary care centres and out of hours services, with a 7.2% increase [95% CI, 5.9–8.5%), but also for uncomplicated urinary tract infections (3.1%; 95% CI, 1.8–4.4%).

ConclusionsA low-intensity multifaceted intervention on management of cystitis, with strong institutional support, resulted in a better choice of antibiotic in antibiotic prescribing, but the intervention had less impact on the adequacy of urine cultures.

Evaluamos el impacto de una intervención multimodal en la mejora del manejo de las cistitis en atención primaria.

DiseñoEstudio de calidad antes-después.

EmplazamientoCentros de atención primaria de la ciudad de Barcelona proporcionados por el Institut Català de la Salut.

ParticipantesLa intervención multimodal consistió en: (1) creación de un grupo de trabajo con líderes en cada uno de los equipos de atención primaria, servicios de urgencias, centros de atención sexual y reproductiva y servicio de atención domiciliaria, (2) sesión formativa sobre el manejo de las infecciones del tracto urinario en cada centro, (3) retorno de resultados a profesionales, y (4) difusión de infografías a profesionales y pacientes. Las intervenciones comenzaron en noviembre de 2020 y finalizaron en verano de 2021.

Mediciones principalesVariación en la prescripción de antibióticos de primera línea, uso de antibióticos y solicitud de urocultivos antes y después de esta intervención.

ResultadosLas sesiones de formación se realizaron en el 93% de los centros. La selección de fármacos de primera línea en cistitis aumentó en un 6,4% después de la intervención (intervalo de confianza [IC] 95%: 5,7-7,1%). El uso de nitrofurantoína en cistitis recurrente aumentó, principalmente en servicios de urgencias (8,7%; IC 95%: 5,2-12,2%). Las solicitudes de urocultivos aumentaron después de la intervención en equipos de atención primaria y servicios de urgencias en cistitis recurrentes (7,2%; IC 95%: 5,9-8,5%), pero también en cistitis simples (3,1%; IC 95%: 1,8-4,4%).

ConclusionesUna intervención multimodal de baja intensidad sobre el manejo de las cistitis junto con el apoyo institucional explícito mejoró claramente la selección de antibióticos, pero tuvo menos impacto en la adecuación de los urocultivos.

Due to rising antimicrobial resistance and adverse events associated with inappropriate antibiotic use, regulatory agencies require that all primary care centres (PCC) have an antimicrobial stewardship programme in place.1 Since the majority of antibiotic usage is in the outpatient setting, antimicrobial stewardship programmes, defined as structured programmes to promote the rational use of antibiotics, are becoming increasingly common because of their potential benefits in process and patient outcomes.2

Various models of implementing outpatient antimicrobial stewardship have been evaluated, including clinician education3, electronic clinical decision support,4 audit and feedback,5 among others.6–8 Existing evidence suggests that among strategies aimed at reducing antimicrobial prescription rates in primary care those based on multiple approaches are the most effective and when several interventions overlap, greater impact is expected, but they are also more difficult to implement.9 Providing feedback of the overall volume of a clinician's antibiotic prescribing, and specifically addressing the appropriateness of treatment for a particular condition, is a less resource-intensive approach that may be attractive to programmes initiating outpatient stewardship.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common problem in primary care consultations. In more than 80% of cases uncomplicated UTI is caused by Escherichia coli.10 In many clinical settings, urine cultures are not routinely performed and women with symptoms of acute cystitis are treated empirically. Thus, empirical treatment in UTIs should cover E. coli. However, resistance of uropathogens to the classical antibiotics has significantly increased in southern Europe countries, mainly because of the high use of antibiotics.11 The resistance of enterobacteria to third generation cephalosporins, mediated by the production of extended spectrum β lactamases (ESBL), is a growing problem in E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Indeed, in 2019, more than half of the E. coli isolates reported to the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) and more than a third of the K. pneumoniae isolates were resistant to at least one antimicrobial group under surveillance.12 According to recent data, the percentage of E. coli resistance to quinolones, cotrimoxazole and amoxicillin and clavulanate, albeit variable, ranges from 20 to 40% in Spain.13,14 According to the recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, empiric antibiotic therapy should be substituted when the rates of resistance surpass 20%.15 Therefore, encouraging appropriate use of first-line antibiotic regimens for UTIs, mainly uncomplicated UTIs and recurrent UTIs in symptomatic women, is paramount. Current Spanish guidelines recommend prescribing a single 3g dose of fosfomycin or nitrofurantoin 100mg t.i.d. for five days for women with uncomplicated cystitis.16,17 The rationale of this strategy is based on the narrow spectrum of aetiologic agents causing acute cystitis and knowledge of their local antimicrobial resistance patterns.18 Over the last years the use of fosfomycin as the preferred therapy for these infections has significantly increased in our country. However, more than half of the Spanish doctors prefer the use of short-course therapies over single-dose therapy for uncomplicated cystitis and standard antibiotic regimens of broad-spectrum antibiotic courses instead of shorter therapies of narrow-spectrum antibiotic regimens for recurrent therapies.19–21 This compromises our pursuit to curb antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens.

An ideal outpatient antimicrobial stewardship programme would have a low barrier to implementation, use easily gathered data, decrease inappropriate antibiotic use, and increase guideline concordance for treating such a common infectious condition. Our objective was to increase the appropriate management of cystitis in adult women through a simple multifaceted intervention in Catalonia.

MethodsStudy design and participantsWe conducted a before and after quality improvement, quasi-experimental study in the primary care setting in Barcelona, including all the PCCs, primary care out of hours (OOH) services and primary care sexual and reproductive services (SRS), and the home visit service, belonging to the Catalonian Institute of Health, which covers 74.6% of the adult population in Barcelona.22 A healthcare professional was chosen in each of these settings and acted as leaders for appropriate antibiotic use.

Simple multifaceted interventionThe multifaceted intervention, which received strong institutional support, consisted of: (a) the creation of a group with a leader in each of the 51 PCCs, 4 OOH services, 3 SRSs and the home visit service; (b) a 45-minute session on management of uncomplicated and recurrent cystitis in each centre; (c) feedback on antibiotic prescribing for uncomplicated and recurrent cystitis at the centre and individual level; (d) a provision of infographics for healthcare professionals (doctors and nurses) as described in Appendix 1; (e) an infographic for patients with uncomplicated and recurrent cystitis (Appendix 2); and (f) updated information about the local resistance of uropathogens (Appendix 3).

Interventions started in November 2020 and ended in the summer of 2021. We set up three different outcomes: (a) variation in the prescription of first-line antibiotics for the empiric treatment of both uncomplicated (either a single-dose 3g fosfomycin sachet or nitrofurantoin 100mg t.i.d. for five days) and recurrent UTIs, defined as ≥3 episodes of cystitis in one year or at least two in six months (either two doses of fosfomycin 3g or full regimen of nitrofurantoin 100mg t.i.d. for seven days as described in local guidelines) before and after the intervention; (b) variation in the total usage of antibiotics before and after the intervention; and (c) request for urine cultures before and after this intervention. The request for urine cultures, in the context of women with UTIs, is only recommended in uncomplicated cystitis which, despite appropriate antibiotic treatment, remains symptomatic (post-treatment urine culture), presents recurrent episodes of cystitis (pre-treatment urine culture) and cystitis in pregnancy (pre- and post-treatment urine culture).

Data sources and measuresAggregated antibiotic prescribing data (ATC J01 class) were extracted from the computerised pharmacy records of dispensed drugs reimbursed by the Catalan Health Service. Authors accessed aggregated data, meaning that individual patients could not be identified. Antimicrobial consumption rates were expressed in defined daily doses (DDD) per 1000 inhabitants-days (DID). Consumption of the following classes of antibiotics was measured: overall rate of antibiotic prescribing (DID J01 of antibacterials for systemic use), DID of beta-lactam antibacterials, penicillins (J01C); DID of other beta-lactam antibacterials, cephalosporins (J01D); DID of quinolones (J01M); DID of macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins (J01F), and special mention to the group of other antibacterials (J01X): J01XX01 (fosfomycin) and J01XE (nitrofuran derivatives).

Data on adequacy of the use of antibiotics and adequacy of the request for urine cultures were extracted anonymously from the electronic primary care medical records of the Catalonian Institute of Health (ECAP). The ECAP database contains longitudinal information on demographic variables, diagnoses, diagnostic test requests, and prescriptions, among other data. Since December 2019, in Catalonia it is mandatory to report the diagnosis that motivates each antibiotic prescription, thereby allowing high quality evaluation of the adequacy of prescription-indication.

Statistical analysisDescriptive analysis of the data was performed before application of chi square tests to compare the percentages of usage of drugs and urine cultures requested before and after the intervention, and 95% confidence intervals of the absolute difference observed between the two periods were calculated, with differences being considered statistically significant when the p-value was <0.05.

Ethics statementThis study was granted an exemption from the Ethical Committee Board Jordi Gol i Gurina (Barcelona, Spain), as ethical approval for quality improvement studies is not required in Spain.

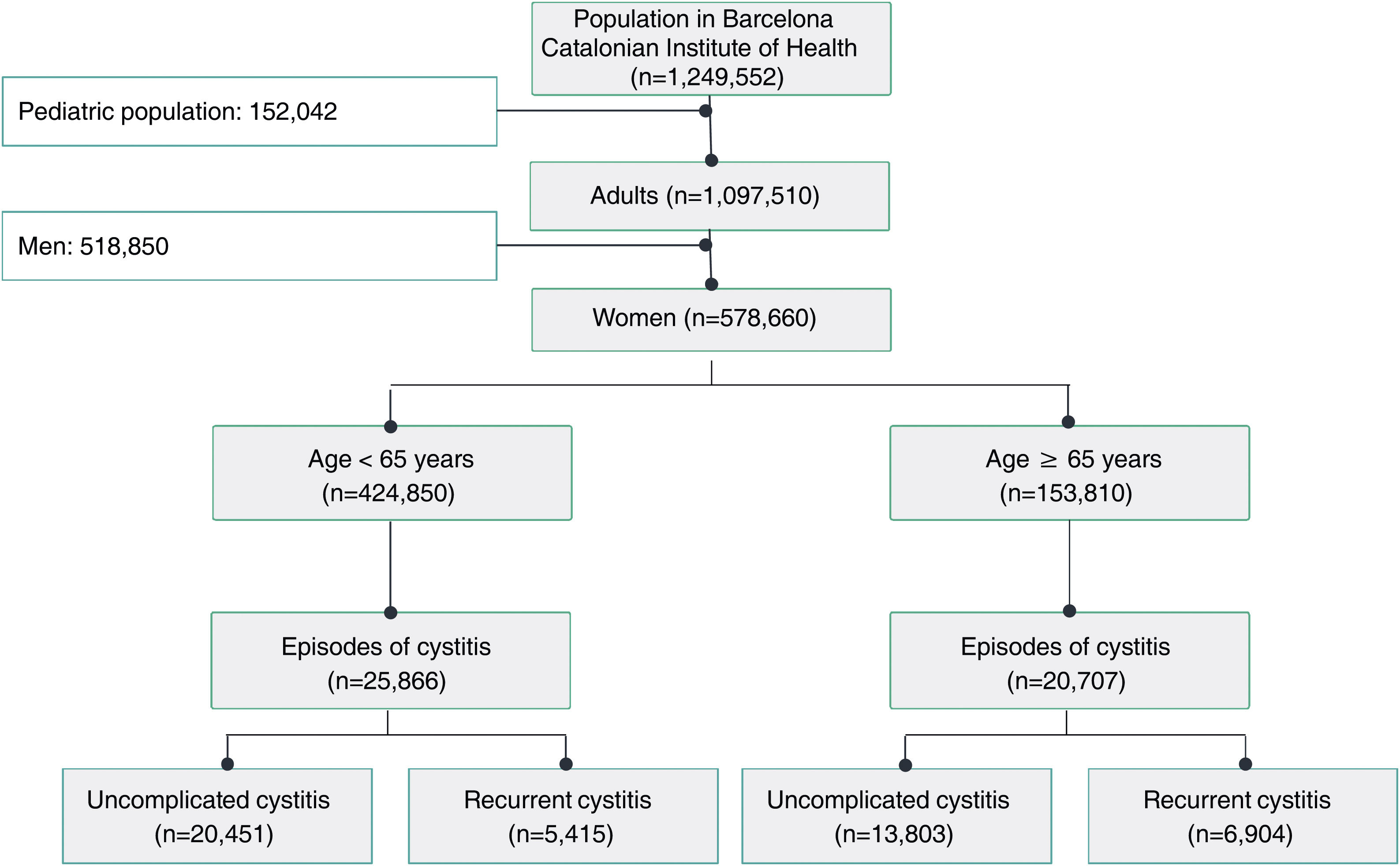

ResultsA total of 54 training sessions took place in 51 centres, encompassing PCCs, OOH services, SRCs and the home visit service, and accounting for 93% of all the centres subject to intervention, with multidisciplinary attendance by both medical and nursing professionals (Appendix 4). In 2021, 46,573 episodes of cystitis were treated in 31,041 adult women in Barcelona PCCs. The mean age of the women treated with antibiotics was 57 years (SD 24.2 years). A total of 34,254 (73.5%) of the treated cystitis corresponded to uncomplicated episodes, and 44.4% of the episodes of cystitis were diagnosed in older women (over 65 years). In this latter population group, the percentage of recurrent cystitis was 33.3% (Fig. 1).

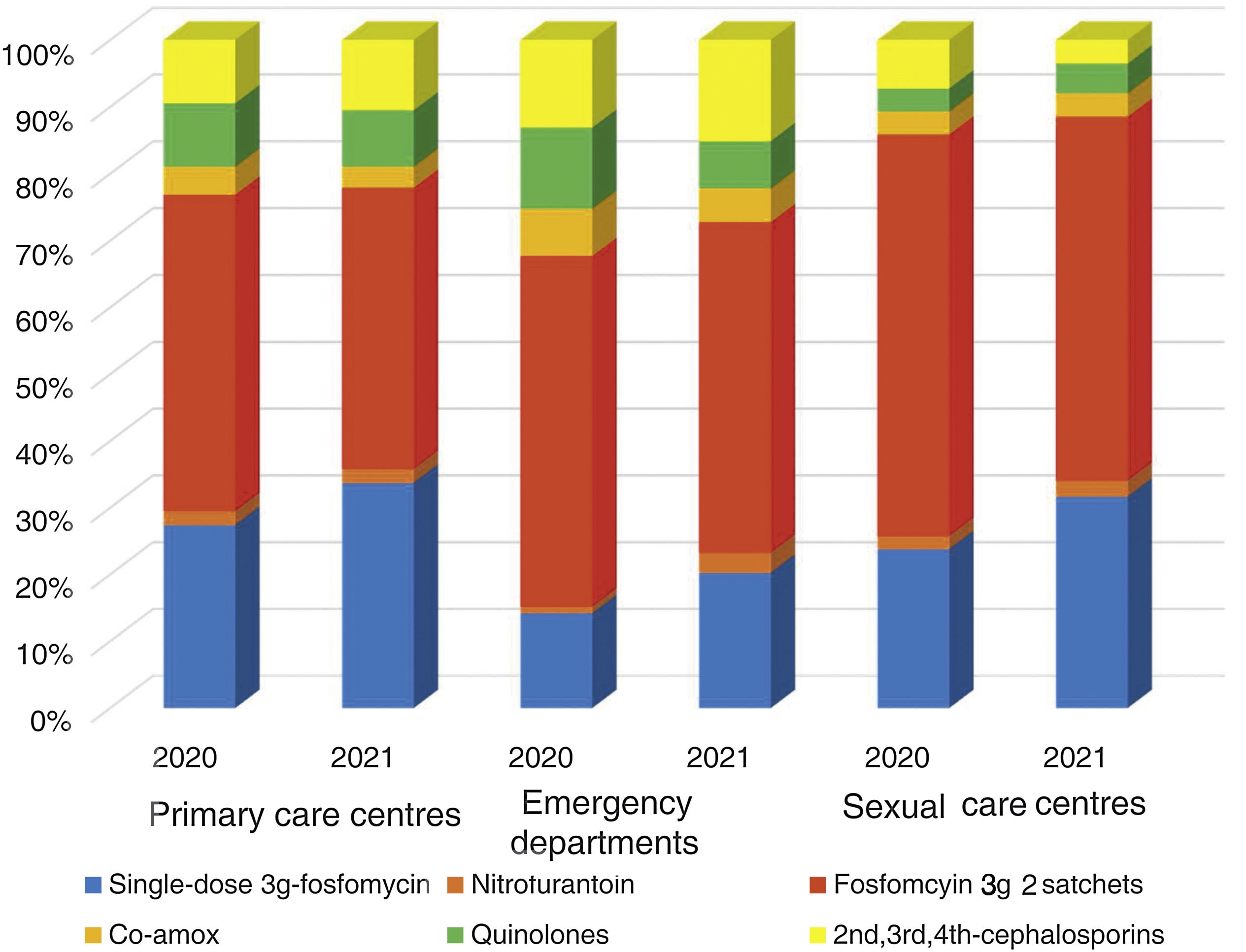

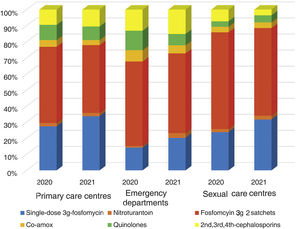

The overall consumption of antibiotics in the PCCs decreased by 2.3% in 2021 compared to 2020, but the reduction was 29% compared to 2019 (pre-pandemic year) (Appendix 5). The use of first-line antibiotics for uncomplicated cystitis in the three primary care settings increased after the intervention in 6.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.7–7.1%; 27.4% in 2020 and 33.8% in 2021). As shown in Fig. 2, the adequacy of antibiotic use in uncomplicated UTIs in the PCCs increased by 6.3% (95% CI, 5.6–7.1%; 28.3% in 2020 vs. 34.6% in 2021). Conversely, consumption of the presentation of 2 sachets of fosfomycin decreased from 44.9% to 40.1%. The appropriateness of the use of first-line antibiotics in the OOH centres was also higher after the intervention (14.4% in 2020 vs. 21.1% to 2021) with a difference of 6.7% (95% CI, 4.2–9.2%). Similarly, the adequacy of antibiotic prescription among the SRCs increased by 33% (23.1% in 2020 vs. 30.8% in 2021; difference of 7.1% [95% CI, 1.4–12.8%]).

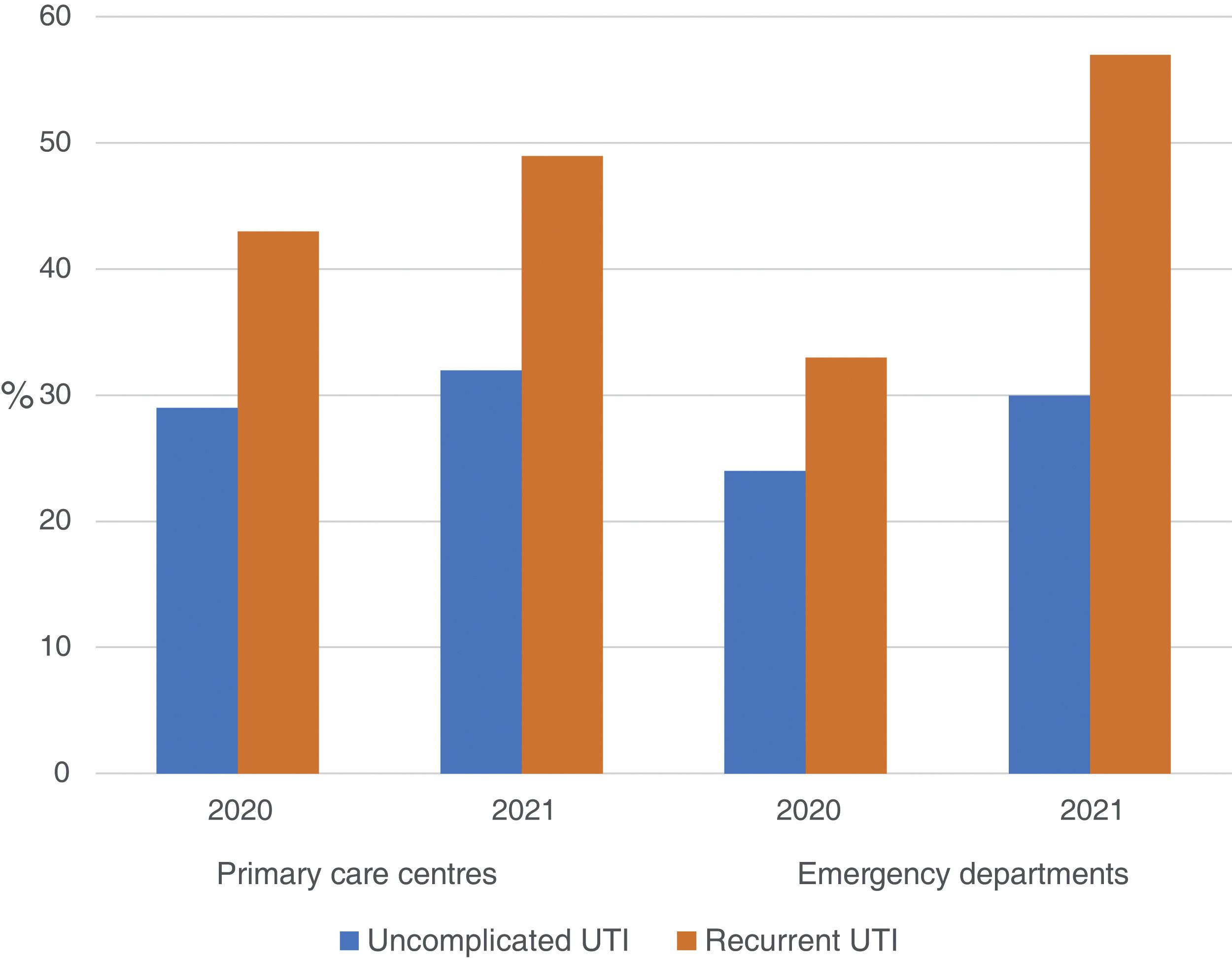

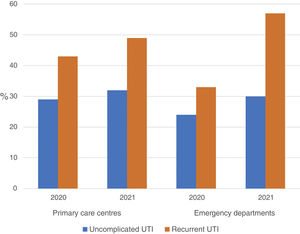

The use of nitrofurantoin for recurrent episodes of cystitis slightly increased in the PCCs (4.5% in 2020 vs. 7.9% in 2021), with a 3.4% increase (95% CI, 2.8–4.1%), but this increase was more pronounced in the emergency departments (8.7% increase; 95% CI, 5.2–12.2%) (Appendix 6). Overall, the use of 2 sachets of 3g of fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin, the drugs recommended as first-choice empirical therapies for recurrent UTIs, remained unchanged in the two settings, with an increase of 0.9% observed in PCCs after the intervention (95% CI, −0.4% to 2.2%). The intervention had less impact on the adequacy of diagnostic tests, showing an increase in the request for urine cultures, in both uncomplicated UTIs (potentially inadequate evidence) and recurrent cystitis (adequate). The adequacy of urine cultures in recurrent UTIs significantly increased in both the PCCs and the OOH centres after the intervention (41.8% in 2020 vs. 49% in 2021; increasing in 7.2% [95% CI, 5.9–8.5%]), but this increase in the urine culture ordering was also statistically significant in cases of uncomplicated UTIs, with an increase in 3.1% (95% CI, 1.8–4.4%) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionWe demonstrate that a simple multifaceted stewardship intervention comprised of clinician education, feedback, and the provision of simple information for healthcare professionals and population with UTIs significantly improved antibiotic prescribing for UTIs, including an increase in the number of first-line antibiotic regimens for uncomplicated UTIs and a reduction in the number of 2 doses of 3g of fosfomycin. However, this intervention failed to reduce the number of urine cultures ordered for uncomplicated UTIs as this request increased in both uncomplicated and recurrent UTIs.

Strengths and limitationsThis study consisted of a large population, including a whole city and all prescriptions dispensed by general practitioners, professionals working in OOH centres, SRCs and a home visit service of a public healthcare service, thus providing a complete picture of overall antibiotic prescribing in primary care in the whole city. Our findings may be applied to other health services with the same characteristics. However, there are several study limitations. First, this study describes a non-randomised, pre-post analysis of an intervention in different settings in primary care. Without randomisation or a control group, we cannot exclude that the Hawthorne effect or temporal or secular trends contributed to our findings. We cannot exclude the possibility that factors other than these interventions could influence antibiotic prescribing during the study period. Second, while we used different types of PCCs, including mainly PCCs as well as OOH centres and SRCs, secondary care settings were not included. As a result, our results need to be validated in other settings. Third, the effect of the pandemic regarding the improvement in the use of first-line antibiotics is uncertain. Fourth, as our intervention was multifaceted, we cannot quantify the extent to which each component individually contributed to our results. Finally, the data refer to the prescriptions made in primary care of the public health service. There has been no follow-up of the prescriptions to outpatients by hospital prescribers. Despite all these limitations, we consider that the simplicity of the intervention used in our multifaceted approach is crucial.23 This, along with the strong institutional support, are the greatest strengths of the study, and allow the reproducibility of our research to other areas.24

Comparison with other studiesOne of the main objectives of the Spanish Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance is the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in the community (PROA in Spanish).25 Our study clearly aligns with this goal, for such a common condition that is linked to increasing antimicrobial resistance levels in our country. Low-intensity multifaceted interventions have shown to be effective in improving the management of cystitis at different levels of care.26,27 Training sessions and the availability of infographics with summarised information on the management of cystitis together with feedback to professionals are the most widely used strategies. We observed a global percentage of adaptation to the recommendations of 34% after our intervention; however, this result is slightly lower than that observed in other studies which achieved an improvement of 41% after carrying out the multifaceted intervention.27 Different factors may have influenced these results. In our setting, the primary care PROA programme has recently been created and is still in a consolidation phase.

On the other hand, the different recommendations related to the first-line drugs for the management of cystitis, depending on the local susceptibility profile, makes it difficult to compare our results with other studies.28,29 In our territory, fosfomycin is widely used for the management of cystitis. Of note in our study was the reduction in the prescription of 2 sachets of fosfomycin in the context of a simple cystitis. We have not identified studies that analyse the impact of a multifaceted intervention on the prescription of fosfomycin trometamol. The percentage of prescription observed for other therapeutic groups such as quinolones in cystitis in our study was 8%, similar to that observed in other more recently published studies.28

Regarding the inappropriateness in the request for urine cultures, different studies have reported percentages ranging from 14% to 33%.30,31 In our study, the percentage of inappropriateness in uncomplicated cystitis was 32%, similar to that observed in other studies. However, regarding the request for urine cultures for recurrent cystitis, this percentage was only 49%.

Implications for practiceDespite our success in reducing overall and non-first choice antibiotic courses for UTIs and increasing optimised treatment, it is important to acknowledge that the use of second-line antibiotic courses remained unnecessary or not optimised in a high percentage of cases. Another obvious area for improvement is in the use of second, third and fourth generation cephalosporins and fluroquinolones. Moreover, there were no improvements in the request for urine culture in uncomplicated cases after the intervention, an untoward and unexpected result. Our experience highlights several areas for future improvement. We are planning to continue our intervention with a second 45-minute session in all the centres as a reminder of all these outcomes and emphasising when urine cultures should be ordered and when not.

In conclusion, we show that an easy-to-implement, non-labour-intensive outpatient stewardship intervention centred on simple strategies targeting not only the healthcare professionals but also the population achieved reductions in unnecessary second-line antibiotic usage while increasing optimised treatment. Our approach had a low barrier to implementation and required a relatively small commitment of resources once education was complete and processes were in place. Therefore, the intervention described here is an efficient model for healthcare systems looking to initiate antimicrobial stewardship in primary care settings for this prevalent infectious disease in particular.

- •

The use of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in primary care has significantly increased in the last years as a result of the increase in the antimicrobial resistance.

- •

Most effective strategies designed to improve managements of infectious diseases in primary care have multiple and complicated approaches.

- •

Study designs aimed at improving the management of infectious diseases in primary care must be as simple as possible.

- •

A simple multifaceted intervention on management of cystitis was designed consisting of group of leaders in different sites, one session, feedback on antibiotic prescribing and updated resistance of uropathogens, and provision of infographics for professionals and patients.

- •

This simple multifaceted intervention accompanied with strong institutional support resulted in an increased percentage of first-line antibiotics prescribed.

- •

The improvement in the prescribing behaviour achieved after the intervention was not accompanied by an increase in the adequacy of urine cultures.

None declared.

Ethical considerationsThis study was granted an exemption from the Ethical Committee Board Jordi Gol i Gurina (Barcelona, Spain), as ethical approval for this type of studies is not required in Spain.

Conflict of interestC.L. declares having reported funds for research from Abbott Diagnostics. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

The authors wish to thank institutional support, the members of PROA-ICS Barcelona Study Group and leaders in the different centres.

PROA-ICS Barcelona Study Group: M. Estrella Barceló Colomer (Muntanya District), Gladys Bendahan Barchilon (Esquerra District), Albert Boada Valmaseda (Àrea Assistencial del Servei Català de la Salut), M. Eugènia Buil Arasanz (Raval Nord Health Centre), Josep M. Cots (La Marina Health Centre), M. Amparo de la Poza Abad (Carles Ribas Health Centre), Pilar Enseñat Grau (nurse, Verneda Sud Health Centre), Eladio Fernández Liz (Muntanya District), Jordi Gost Rosquellas (Home Visit Unit), Marta Lestón Vázquez (Dreta District), Ana López Plana (Bon Pastor Health Centre), Joan A. Vallés Callol (Litoral District), Noemí Villen Romero (Dreta District).

Leaders in the different centres: Lidia Arpal Sagristà, Maria Atero Villén, Marta Badia Capdevila, Jesús Bellido Casado, Xavier Blancafort Sansó, Cristina Boté i Fernández, M. Eugenia Buil, Oriol Caixés Valverde, Silvia Calvet Junoy, Carmen Cid Gil, Josep M. Cots Yago, Leticia Cuenca Rodríguez, Maribel Cuenda Macias, Marta Cuní Munné, M. Amparo de la Poza Abad, Silvia Ferrer Moret, Yolanda García Fernández, Carolina Guiriguet Capdevila, Mercè Hernández Bonet, M. José Herrero Martínez, M. Ángeles Hortelano García, Reis Isern Alibes, Ana Jiménez Lozano, Yolanda Linares Sicilia, Natalia López Pareja, Ana M. López Plana, Ana Luque Alonso, Ricard Martínez Sala, Maria Miracle Fandós, Laia Montoya Salvadó, Sandra Moreno Cotés, Miriam Muñoz López, M. José Nieto López, Clara Ortí Segarra, M. Ángel Pérez Gómez, Leila Pifarré Portella, Melania Priego Artero, Iris Rivera Abelló, Brenda Riesgo Escudero, Aurora Rovira Fontanals, J. Ignacio Rodríguez Gómez, Ramón A. Rodríguez González, Sonia Rodríguez Martínez, Laura Rubio Pérez, Carlos Rueda Beas, Patricia Sala Sola, Elena Scazzocchio Dueñas, Neus Soler Solé, Julián Soto Marata, Sergi Surkov Daniluk, Trinitat Tovar Velasco, Carme Troyano Cussó, Mireia Valle Calvet, Sandra Veloso Rodríguez, Èlia Vinyes Roca, and Lucia Vivas Camino.