To determine the epidemiology of heart failure registered in primary healthcare clinical records in Catalunya, Spain, between 2010 and 2014, focusing on incidence, mortality, and resource utilization.

DesignRetrospective observational cohort study.

SettingStudy was carried out in primary care setting.

Participants and interventionsPatients registered as presenting a new heart failure diagnosis. The inclusion period ran from 1st January 2010 to 31st December 2013, but patients were followed until 31st December 2013 in order to analyze mortality.

Main measuresInformation came from electronic medical records.

ResultsA total of 64441 patients were registered with a new diagnosis of heart failure (2.76 new cases per 1000 persons-year). Among them, 85.8% were ≥65 years. The number of cases/1000 persons-year was higher in men in all age groups. Incidence ranged from 0.04 in women <45 years to 27.61 in the oldest group, and from 0.08 in men <45 years to 28.52 in the oldest group. Mortality occurred in 16305 (25.3%) patients. Primary healthcare resource utilization increased after the occurrence of heart failure, especially the number of visits made by nurses to the patients’ homes.

ConclusionHeart failure incidence increases with age, is greater in men, and remains stable. Mortality continues to be high in newly diagnosed patients in spite of the current improvements in treatment. Home visits represent the greatest cost for the management of this disease in primary care setting.

Determinar la epidemiología de la insuficiencia cardíaca registrada en las historias clínicas de atención primaria en Cataluña, España, entre 2010 y 2014, centrándose en la incidencia, la mortalidad y la utilización de recursos sanitarios.

DiseñoEstudio de cohorte observacional retrospectivo.

EmplazamientoEl estudio se llevó a cabo en atención primaria.

Participantes e intervencionesPacientes registrados con nuevo diagnóstico de insuficiencia cardíaca en el período de estudio. El período de inclusión fue del 1 de enero de 2010 al 31 de diciembre de 2013, pero los pacientes se siguieron hasta el 31 de diciembre de 2014 para poder determinar la mortalidad.

Mediciones principalesLa información se obtuvo de la historia clínica electrónica de los participantes.

ResultadosSe registraron un total de 64.441 pacientes con nuevo diagnóstico de insuficiencia cardíaca (2,76 nuevos casos/1000 personas-año). De ellos, el 85,8% tenían ≥65 años. El número de casos/1000 personas-año fue mayor en hombres en todos los grupos de edad. La incidencia varió de 0,04 en mujeres <45 años a 27,61 en el grupo de mayor edad, y de 0,08 en hombres <45 años a 28,52 en el grupo de mayor edad. La mortalidad se produjo en 16.305 (25,3%) pacientes. La utilización de los recursos de atención primaria aumentó tras el diagnóstico de insuficiencia cardíaca, especialmente el número de visitas realizadas por las enfermeras a los pacientes en su domicilio.

ConclusiónLa incidencia de insuficiencia cardíaca aumenta con la edad, es mayor en hombres y se mantiene estable en el tiempo. La mortalidad continúa siendo alta en pacientes recién diagnosticados a pesar de las mejoras actuales en el tratamiento. Las visitas domiciliarias representan el mayor coste para el manejo de esta enfermedad en el ámbito de atención primaria.

Heart failure (HF) is a growing public health concern and accounts for 1% of the general adult population.1 In Spain more than 10% of those aged >70 years are affected by HF, and it has become the third leading cause of death.2 Moreover, since current therapies prolong the lives of HF patients in the following decades its incidence is expected to increase.3 This does, however, depend on the diagnostic criteria employed and population studied,4 HF epidemiology has changed, and a decline in incidence has even been reported.5

A recent Spanish publication, using an administrative database to identify HF codified according to the International Codification Disease 9th revision (CIE-9), reported an incidence of 2.78 per 1000 persons-year.6

An ever-increasing number of healthcare resources are employed in attending HF patients.7–9 In Europe the economic burden of managing HF accounts for almost 7% of the global healthcare expenditure,10 the main cost coming from hospitalizations.11,12 Although there has been an improvement in prognosis, mortality in the first three years following diagnosis remains close to 25%.13,14

This study aims to determine the epidemiology of HF registered in the primary healthcare records in Catalunya, Spain, between 2010 and 2013. It focuses on HF incidence, mortality, and PHC resource utilization.

MethodsStudy designA retrospective observational cohort study based on PHC electronic medical records (EMR). Its objective was to determine the incidence, healthcare resource utilization, and mortality of HF patients attended in PHC.

Study periodThe study period ran from 1st January 2010 until 31st December 2013, but patients were followed until 31st December 2013 in order to analyze mortality.

Study populationInformation came from the EMR of PHC patients ≥18 years attended at any of the 279 centres managed by the Catalan Institute of Health, Spain.

VariablesTo estimate incidence we analyzed the new HF cases that occurred among the 5165778 individuals residing in Catalunya during the study period who were free from this disease at baseline.

Comorbidities and demographic information were taken at the moment of HF onset. Mortality was calculated as all-cause death for the incident cases.

Age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, and associated comorbidities were also recorded.

Diagnoses were registered following the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes: heart failure [HF(I50)], dementia (F00–F03), anaemia (D50–D64), atrial fibrillation [AF(I48)], cancer (C00–C97), chronic kidney disease [CKD(N18)], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD(J40–J44)], diabetes mellitus(E10–E14)], depression (F32–F33), lipoprotein metabolism disorders and other lipidaemias (E78), hypertension (I10–I15), peripheral artery disease (I73.9), coronary heart disease [CHD(I20–I25)], stroke (I63–I65), and obesity (E66.0–66.2, E66.8–E66.9).

Data sourcesData were obtained from the SIDIAP database (Information System for the Enhancement of Research in Primary Care)15 which stores records from routine PHC clinical practice. An anonymization algorithm was used to encrypt the information.

Costs and healthcare resource utilization were calculated according to the following: PHC nurse consultations/home visits, laboratory tests, PHC General Practitioner (GP) consultations/home visits, and primary care emergency consultations.

Statistical analysesContinuous variables were summarized and mean and standard deviations calculated to describe the cohorts. Categorical variables were summarized by frequency and percentage.

The incidence of HF was computed between 2010 and 2013 in the population at risk without prior HF diagnosis on 1st January 2010. Incidence rates were calculated as the number of patients with HF divided by the sum of all individual-time at risk out of 5165778 subjects. In order to determine mortality, patients were followed until 31st December 2014.

All-cause mortality rates for patients in the incident cohort were computed as the number of patients who died divided by the sum of all individual-time at risk since the diagnosis was recorded. Individual-time at risk for the outcome was defined as the number of days from incidence date to the date of death or to end of follow-up, whichever occurred first.

Cox regression models were performed to estimate mortality rate related with comorbidities. Crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were calculated. The models were constructed using the covariates clinically associated with HF incidence. Furthermore, the HR were computed specifically by age group. Resource utilization was assessed before and after HF diagnosis.

Data management and statistical analysis were performed with R3.5.1 statistical package.

EthicsThe study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee, Institut Universitari d’Investigació en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol (IDIAP Jordi Gol) (Ref: P15/147). All data were anonymized, and EMR confidentiality was respected in accordance with national and international regulations regarding personal data protection.

ResultsIncidenceMedian follow-up was 21 (interquartile interval 10–36) months.

A total of 64441 patients had a new HF diagnosis recorded between 2010 and 2014, a figure that represents 2.76 new cases per 1000 persons-year. Among the patients 85.8% were >65 years.

Men presented higher rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, and cancer. Women presented higher rates for obesity, anaemia, atrial fibrillation, depression, dyslipidemia, and hypertension (Table 1). The incidence of HF remained stable along the study period.

Characteristics of incident heart failure cases.

| Total | Women | Men | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=64441 | N=35832 | N=28609 | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.000 | |||

| <45 | 804 (1.2) | 257 (0.7) | 547 (1.9) | |

| 45–54 | 2190 (3.4) | 609 (1.7) | 1581 (5.5) | |

| 55–64 | 6105 (9.4) | 2209 (6.1) | 3896 (13.6) | |

| 65–74 | 14518 (22.5) | 7164 (20.0) | 7354 (25.7) | |

| 75–84 | 27959 (43.4) | 16664 (46.5) | 11295 (39.5) | |

| ≥85 | 12865 (20.0) | 8929 (24.9) | 3936 (13.8) | |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Smoking | 6049 (9.3) | 1232 (3.4) | 4817 (16.8) | 0.000 |

| Alcohol | 10633 (16.5) | 2565 (7.1) | 8068 (28.2) | 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 49384 (76.6) | 28931 (80.7) | 20453 (71.5) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 29481 (45.7) | 16892 (47.1) | 12589 (44.0) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 18363 (28.5) | 11415 (31.9) | 6948 (24.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 22093 (34.3) | 11267 (31.4) | 10826 (37.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular comorbidity | ||||

| Peripheral artery disease | 4321 (6.7) | 1322 (3.6) | 2999 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 5709 (8.8) | 1804 (5.0) | 3905 (13.6) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 21985 (34.1) | 12382 (34.6) | 9603 (33.6) | 0.009 |

| Non-cardiovascular comorbidities | ||||

| Anaemia | 12674 (19.7) | 7604 (21.2) | 5070 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 9429 (14.6) | 4282 (12.0) | 5147 (18.0) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 12506 (19.4) | 6962 (19.4) | 5544 (19.4) | 0.879 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 11867 (18.4) | 3526 (9.8) | 8341 (29.2) | 0.000 |

| Depression | 7540 (11.7) | 5601 (15.6) | 1939 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| Mortality during follow-up | 16305 (25.3) | 8709 (24.3) | 7596 (26.6) | <0.001 |

Incidence rates (cases/1000 person/year) in women ranged from 0.04 cases/1000 person/year in those <45 years to 27.61 in the oldest subjects, and from 0.08 in men <45 years to 28.52 in the oldest subjects (Table 2).

Heart failure incidence according to gender and age.

| Age groups | Women | Men | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidente cases | Cumulate incidence | Cases/1000 persons/year | Incidente cases | Cumulate incidence | Cases/1000 person/year | |

| <45 | 257 | 0.02% | 0.04 | 547 | 0.03% | 0.08 |

| 45–54 | 609 | 0.14% | 0.31 | 1.581 | 0.37% | 0.80 |

| 55–64 | 2.209 | 0.65% | 1.37 | 3.896 | 1.22% | 2.62 |

| 65–74 | 7.164 | 2.77% | 5.97 | 7.354 | 3.26% | 7.24 |

| 75–84 | 16.664 | 7.61% | 17.75 | 11.295 | 7.50% | 18.29 |

| ≥85 | 8.929 | 9.22% | 27.61 | 3.936 | 9.06% | 28.52 |

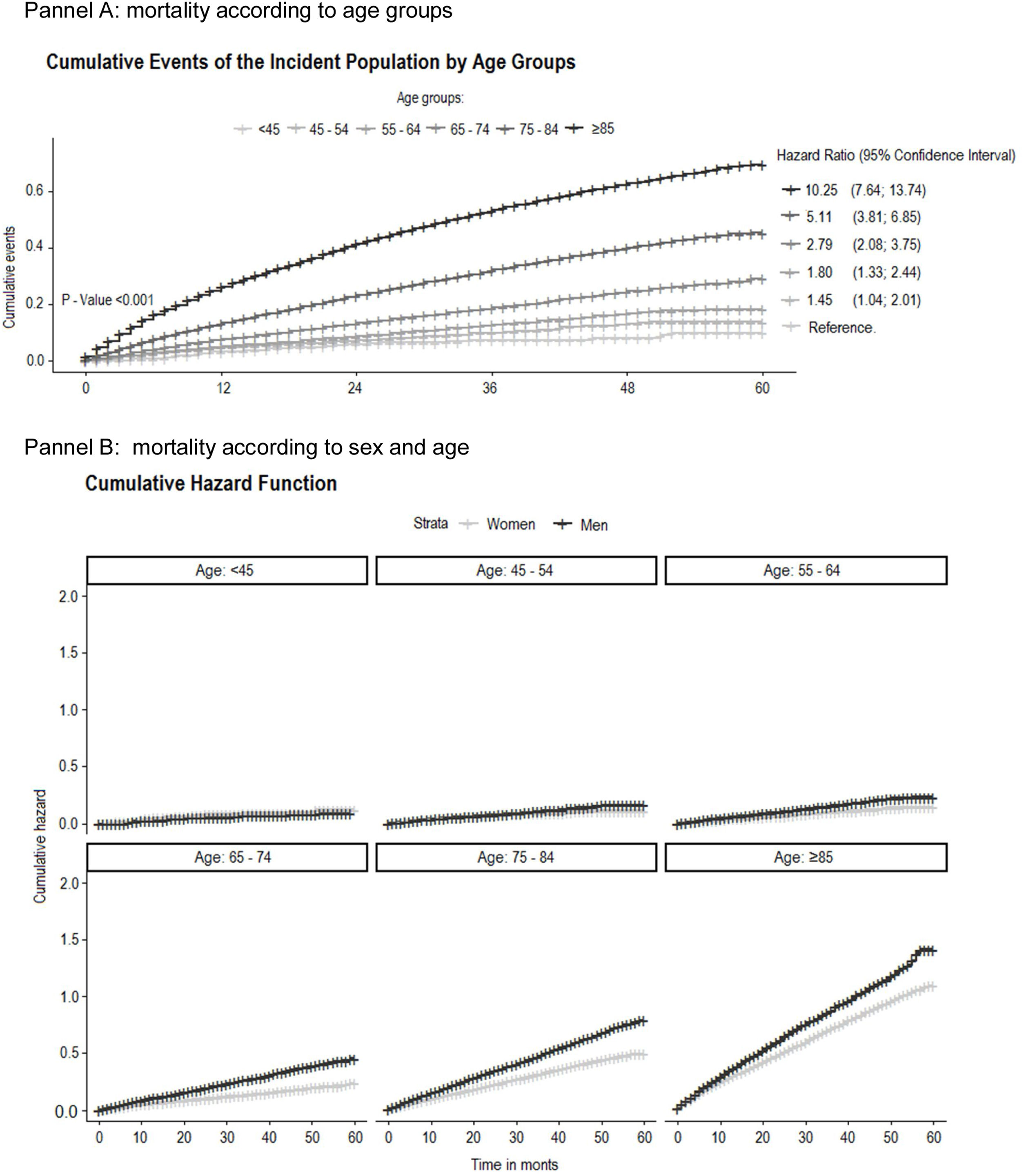

Among the patients who presented incident HF between 1st January 2010 and 31st December 2014, a total of 16305 (25.3%) died during follow-up. Mortality was higher in men than in women (26.6% versus 24.3%, p<0.001, respectively) (Fig. 1).

A total of 10068 patients died during the first year of follow-up (15.6%). This percentage represented 61.7% of mortality in the whole period.

Healthcare resource utilization and costsBefore the first registered HF episode, the median number of consultations with the GP and nurse at the PHC was 19 (interquartile interval 9–34) and 12 (interquartile interval 5–27), respectively. After the first episode, the median number of consultations at the PHC with the GP were 16 (interquartile interval 7–30) and 12 (interquartile interval 5–28) with the nurse. Home visits by the GP increased from 2 (interquartile interval 1–4) to 3 (interquartile interval 1–6) whilst those made by the nurse rose from 3 (interquartile interval 1–10) to 5 (interquartile interval 2–14).

Primary care emergencies were used at least once by 7.27% of the patients following HF diagnosis.

The total number of encounters with PHC professionals increased dramatically after HF occurrence, especially regarding the number of home visits made by the nurses (from 181826 to 318662). The total cost for the PHC as a consequence of HF diagnosis was approximately 223.31 euros/individual/year. When compared to the figure prior to diagnosis this represents a difference of 4553411 euros for the 64441 patients. The global cost was higher in women, who represented the 55.6% of the sample (Table 3).

Differences in primary healthcare resource utilization and costs before and after diagnosis of heart failure by sex (women: 35832 (55.6%) and men 28609 (44.4%).

| Total of encounters (N) | Total cost (€) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After HFa diagnosis | Before HF diagnosis | After HF diagnosis | Before HF diagnosis | |||||||||

| Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | |

| Type of consultation | ||||||||||||

| Nurse at PHCb | 1222671 | 652104 | 570567 | 1198277 | 657062 | 541215 | 34234788 | 18258912 | 15975876 | 33551756 | 18397736 | 15154020 |

| Nurse at patient's home | 318662 | 208595 | 110067 | 181826 | 126576 | 55250 | 14339790 | 9386775 | 4953015 | 8182170 | 5695920 | 2486250 |

| Laboratory testc | 164861 | 90567 | 74294 | 180531 | 99885 | 80646 | 1500235 | 824160 | 676075 | 1642832 | 908954 | 733879 |

| General practitioner at PHCb | 1320889 | 741253 | 579636 | 1526364 | 870065 | 656299 | 52835560 | 29650120 | 23185440 | 61054560 | 34802600 | 26251960 |

| General practitioner visit at patient's home | 128248 | 83651 | 44597 | 86240 | 59298 | 26942 | 8336120 | 5437314 | 2898806 | 5605600 | 3854370 | 1751230 |

| Primary care emergency visits | 30640 | 16039 | 14601 | 8406 | 4945 | 3461 | 1838400 | 962340 | 876060 | 504360 | 296700 | 207660 |

| Total | 3185971 | 1792209 | 1393762 | 3181644 | 1817831 | 1363813 | 113084893 | 64519621 | 48565272 | 110541278 | 63956280 | 46584999 |

| Yearly person cost (€) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After HFa diagnosis | Before HF diagnosis | |||||

| Total | Women | Men | Total | Women | Men | |

| Type of consultation | ||||||

| Nurse at PHCb | 268.68 | 254.55 | 286.90 | 201.60 | 199.33 | 204.43 |

| Nurse at patient's home | 112.54 | 130.86 | 88.95 | 49.16 | 61.71 | 33.54 |

| Laboratory testc | 11.77 | 11.49 | 12.14 | 9.87 | 9.85 | 9.90 |

| General practitioner at PHCb | 414.67 | 413.35 | 416.37 | 366.85 | 377.08 | 354.14 |

| General practitioner visit at patient's home | 65.42 | 75.80 | 52.06 | 33.68 | 41.76 | 23.62 |

| Primary care emergency visits | 14.42 | 13.42 | 15.73 | 3.03 | 3.21 | 2.80 |

| Total | 887.50 | 899.47 | 872.15 | 664.19 | 692.95 | 628.43 |

Incidence of HF increased dramatically with age and was greater in men, particularly in the younger strata populations. Mortality in incident HF patients grew steadily across the age groups, it was ten-fold higher in the oldest group, and was also higher in men. We observed an increment in PHC resource utilization after the first episode of HF registered in the clinical records.

Several factors have been identified in the literature explaining differences in incidence rates. They include methodologies, diagnosis criteria, and HF approaches employed by local health systems. Moreover, it has been reported that diagnosis could be confirmed in only half of the patients labelled as HF in the PHC records.16

Age-adjusted HF incidence may tend to decrease in western countries, possibly due to optimized cardiovascular risk factor management.17 Our findings show that HF incidence remained almost stable along the study period and was much lower in the youngest subjects compared to the oldest. A study from administrative databases in Spain found similar rates to those described in our population.6 The incidence observed by the Rotterdam study was 1.4%.18 Similar results in a Swedish one analysing information from an administrative database.19

Regarding mortality, a meta-analysis of 1.5 million HF patients observed an 87% survival rate the first year and 35% five years after diagnosis. Five-year survival, however, increased from 29.1% in the period before 1979 to 59.7% in the period 2000–2009.20

After a median follow-up of 5 years, a study based on England, found up to 56.1% mortality among incident HF patients.21 A recent publication from Spain found a mortality rate of 14% and was even higher in hospitalized patients (24%).22

Healthcare resource utilization may be approached from a number of perspectives, depending on setting, healthcare system, and variables analyzed. A publication from Spain described a lower number of PHC consultations, but higher emergency care use, in HF patients. Findings probably were due to the sample taken from secondary care and because all subjects were symptomatic at the inclusion baseline.23

In agreement with our research, it has been observed that the highest costs regarding HF patients are related to hospitalization episodes, and, in second term, PHC home visits.24 Findings that concur with another study from an administrative database in Catalunya (Spain) in which the main expense was attributable to hospitalization.25

The number of GP and the PHC nurse home visits increased after the first HF episode, probably due to the inherent limitations of the patient's new condition.

Strengths and limitationsWe analyzed the registered diagnosis from an administrative database oriented towards clinical purposes. It is possible, therefore, that the percentage of HF diagnoses was lower than expected.

Other variables could have been included in the resource utilization category such as medication. Nevertheless, as specific HF medication is usually prescribed by cardiologists after the first HF episode we cannot attribute the cost exclusively to the PHC setting.

Data from this study period do not allow discrimination between reduced and preserved ejection fraction, since this variable was not registered systematically at that time and we found some missing values.

ConclusionIncidence of HF in the adult population increases with age, is greater in men, and remains stable. Mortality continues to be high in newly diagnosed HF patients in spite of the current, improved treatment. The greatest expense resulting from HF management in the PHC setting is due to home visits.

Conflict of interestsNone declared.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Novartis Pharma AG for partially funding this project, and SIDIAP database for providing data.