To compare the effect of discontinuing bisphosphonate treatment on fracture risk in postmenopausal women at high versus low risk of fracture.

DesignRetrospective, longitudinal and population-based cohort study.

SettingBarcelona City Primary Care. Catalan Health Institute.

ParticipantsAll women attended by primary care teams who in January 2014 had received bisphosphonate treatment for at least five years were included and followed for another five years.

InterventionPatients were classified according to their risk of new fractures, defined as those who had a history of osteoporotic fracture and/or who received treatment with an aromatase inhibitor, and the continuity or deprescription of the bisphosphonate treatment was analyzed over fiver year follow-up.

Main measurementsThe cumulative incidence of fractures and the incidence density were calculated and analyzed using logistic regression and Cox models.

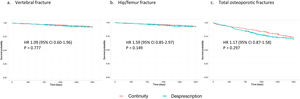

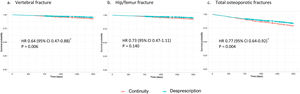

ResultsWe included 3680 women. There were no significant differences in fracture risk in high-risk women who discontinued versus continued bisphosphonate treatment (hazard ratio [HR] 1.17, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.87–1.58 for total osteoporotic fractures). However, discontinuers at low risk had a lower incidence of fracture than continuers. This difference was significant for vertebral fractures (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47–0.88) and total fractures (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.64–0.92).

ConclusionOur results suggest that deprescribing bisphosphonates in women who have already received five years of treatment does not increase fracture risk. In low-risk women, continuing this treatment might could even favor the appearance of new osteoporotic fractures.

Comparar el efecto de la desprescripción de bifosfonatos sobre el riesgo de fractura en mujeres posmenopáusicas con alto y bajo riesgo de fractura.

DiseñoEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo, longitudinal y de base poblacional.

EmplazamientoAtención primaria Barcelona. Institut Català de la Salut.

ParticipantesSe incluyeron todas las mujeres atendidas por los equipos de atención primaria que a enero de 2014 habían recibido tratamiento con bifosfonatos durante al menos cinco años.

IntervenciónSe clasificó a las pacientes según su riesgo de nuevas fracturas, definido como presencia de antecedentes de fractura osteoporótica y/o tratamiento con un inhibidor de la aromatasa, y se analizó la continuidad o desprescripción del tratamiento con bifosfonatos a lo largo de cinco años de seguimiento.

Mediciones principalesLa incidencia acumulada de fracturas y la densidad de incidencia se calcularon y analizaron mediante regresión logística y modelos de Cox.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 3.680 mujeres. No hubo diferencias significativas en el riesgo de fractura en mujeres de alto riesgo que desprescribieron el bisfosfonato comparado con aquellas que continuaron (hazard ratio [HR] 1,17, intervalo de confianza [IC] de 95% 0,87-1,58 para fracturas osteoporóticas totales). Sin embargo, los que discontinuaron con bajo riesgo tuvieron una menor incidencia de fractura que los que continuaron. Esta diferencia fue significativa para fracturas vertebrales (HR 0,64, IC 95% 0,47-0,88) y fracturas totales (HR 0,77, IC 95% 0,64-0,92).

ConclusionesNuestros resultados sugieren que la desprescripción de bifosfonatos en mujeres que ya han recibido cinco años de tratamiento no aumenta el riesgo de fractura. En mujeres de bajo riesgo, la continuación de este tratamiento podría incluso favorecer la aparición de nuevas fracturas osteoporóticas.

Osteoporosis is characterized by a decrease in bone mass and an alteration of the microarchitecture of bone tissue, causing an increase in bone fragility and a higher risk of fractures. Hip fractures account for the highest morbidity and mortality.1

Bisphosphonates, among others, are a group of drugs that are indicated for treating postmenopausal osteoporosis. They act by inhibiting bone resorption, mainly by suppressing the action of osteoclasts,2 and their effect can last for years after withdrawal.3 Despite their demonstrated efficacy in preventing fractures in women with osteoporosis, there is debate about which population subgroup could benefit from this treatment. Indeed, several systematic reviews have assessed the efficacy of alendronate, risedronate and etidronate for primary and secondary prevention of fractures. In postmenopausal women without a previous fracture, they have failed to prove a statistically significant effect,4–6 different institutions and scientific societies have refrained from recommending generalized bisphosphonates in postmenopausal women with low risk of fractures.7–9

However, few studies have assessed the long-term efficacy of bisphosphonates for reducing fracture risk. The most relevant data come from the extension phases of the FLEX trial (with alendronate) and the HORIZON trial (with zolendronic acid).10,11 Neither study found differences in hip fractures or non-vertebral fractures compared to placebo; results in clinical vertebral fractures were not consistent between the two trials. Regarding safety, these drugs present a good safety and tolerance profile in the short term, but serious and potentially disabling adverse reactions have been observed in the long term, including atypical fractures of the femur and osteonecrosis of the maxilla.12 The atypical fractures of the femur, known as subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femur fractures, are fractures in the bone just below the hip joint or those that occur in the long part of the thigh bone, respectively. These serious adverse events have prompted drug regulatory agencies to publish two guidance notes recommending that healthcare professionals periodically re-evaluate the need for bisphosphonate treatment, particularly after five years of treatment.13,14

Currently, the evidence on the cumulative effect of these drugs on bone tissue, together with the controversial efficacy in certain population subgroups and concerns about serious adverse effects associated with long-term use, makes it reasonable to consider deprescribing this treatment in certain postmenopausal women.3 In this line, since 2012 a low-intensity and personalized intervention has been implemented among physicians working in the Barcelona City Primary Care Teams of the Catalan Institute of Health, aimed at promoting the deprescription of bisphosphonates in women after five years of treatment.

Few data are available on the effect of bisphosphonate deprescription for preventing new fractures. Observational studies based on real-world data obtained from daily clinical practice can help complement the safety and efficacy data generated by clinical trials by incorporating information from a large number of patients attended in a real clinical setting.15 Our study thus aims to compare the effect of discontinuing bisphosphonate treatment on fracture risk in postmenopausal women at high versus low risk of fracture.

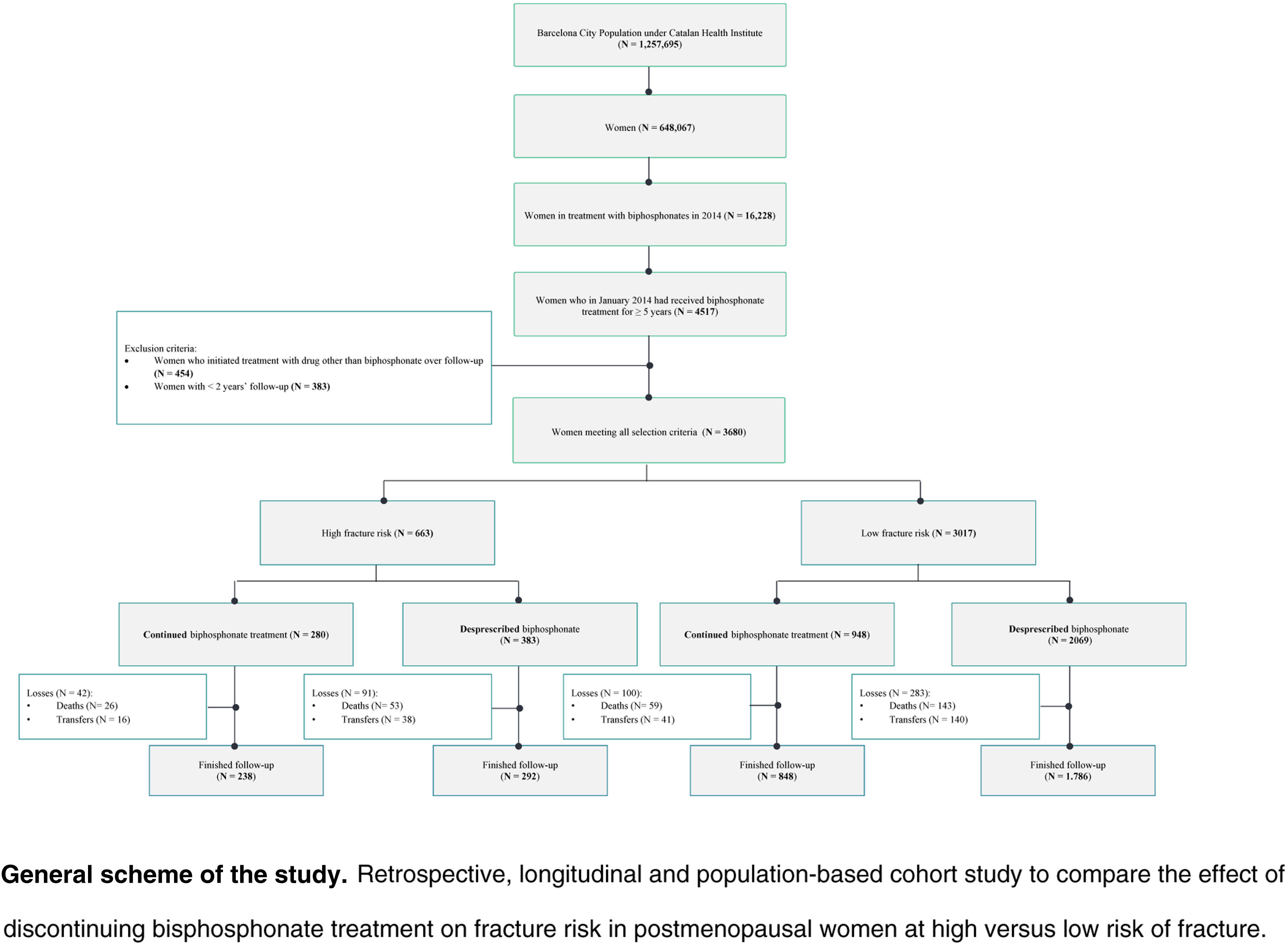

Material and methodsDesign, setting, and study populationRetrospective, longitudinal, population-based cohort study in Barcelona City Primary Care, managed by the Catalan Health Institute and made up of 51 primary care teams, staffed by 754 family and community physicians in the city of Barcelona. The target population is 1,257,695 inhabitants (74.6% of the population of the city of Barcelona), of which 51.5% (648,067 inhabitants) are women.16

The study included all women assigned to the 51 teams of Barcelona City Primary Care who had an active prescription for bisphosphonates in January 2014 and had received bisphosphonate treatment for at least five. The cohort was followed for five years, from January 2014 to January 2019. No new patients were included, and attrition was due to mortality or loss to follow-up when the women were transferred to other healthcare providers or territories. Patients lost to follow-up were not excluded but were censored in the survival analysis. Patients with less than two years of follow-up and those who began treatment with a drug other than bisphosphonate for osteoporosis during the follow-up period were excluded from the study.

Included women were classified according to the risk of developing new fractures. Women at high risk of fracture were defined as those who had a history of osteoporotic fracture17 (fractures that occurred in the previous five years) and/or who received treatment with an aromatase inhibitor during the follow-up period.18,19 We considered women who did not have a history of osteoporotic fracture17 nor were receiving treatment with an aromatase inhibitor to be at low risk of fracture.

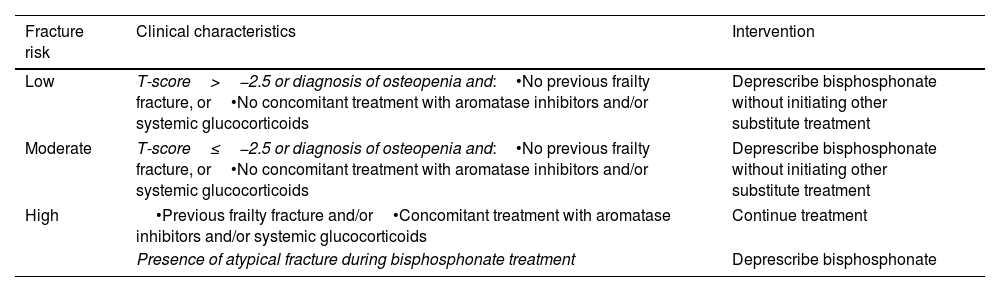

The continuity or deprescription of the bisphosphonate was assessed according to clinical criteria during the follow-up period (Table 1). We analyzed the number of days that the woman was treated with bisphosphonate for each year of follow-up; if the woman had been prescribed the bisphosphonate for at least 150 consecutive days, we considered that she had been taking bisphosphonates for that year. Based on this definition, the women included in the study were classified into patients who were either continuing bisphosphonate treatment (those with an active prescription for ≥60% of the follow-up period) or who were deprescribed bisphosphonate treatment (active prescription for <60% of the follow-up period). Supplementary Figure 1 shows an explanatory scheme of the study design.

Recommendations for deprescription of bisphosphonates in postmenopausal women after five years of treatment in Barcelona primary care.

| Fracture risk | Clinical characteristics | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Low | T-score>−2.5 or diagnosis of osteopenia and:•No previous frailty fracture, or•No concomitant treatment with aromatase inhibitors and/or systemic glucocorticoids | Deprescribe bisphosphonate without initiating other substitute treatment |

| Moderate | T-score≤−2.5 or diagnosis of osteopenia and:•No previous frailty fracture, or•No concomitant treatment with aromatase inhibitors and/or systemic glucocorticoids | Deprescribe bisphosphonate without initiating other substitute treatment |

| High | •Previous frailty fracture and/or•Concomitant treatment with aromatase inhibitors and/or systemic glucocorticoids | Continue treatment |

| Presence of atypical fracture during bisphosphonate treatment | Deprescribe bisphosphonate | |

At the beginning of each year, family physicians were sent a list of their patients in treatment with bisphosphonates for at least five years, together with an information letter and evidence sheets justifying their withdrawal. The physicians themselves then made the final determination on the appropriateness of deprescribing the medication, based on the individual patient's clinical characteristics. Every three months the doctors received feedback on the drugs withdrawn.

Information sourcesAll data were extracted anonymously from the electronic medical records for primary care of the Catalan Institute of Health (ECAP). The ECAP database contains longitudinal information on demographics, socioeconomic status, diagnoses, symptoms, and prescriptions, among other data.

VariablesThe following variables were collected:

- •

Demographic variables: age, sex and the MEDEA deprivation index.20 This index, used in the ECAP, categorizes census tracts into quintiles based on their socioeconomic situations. People residing in quintile 1 (Q1) have the lowest level of deprivation, while those living in Q5 areas have the highest level of deprivation.

- •

Diagnostic variables: diseases were coded in the ECAP using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). Diagnostic codes for osteoporotic fractures were identified (Supplementary Table 1). We analyzed vertebral, hip, or femur fractures, and total osteoporotic fractures. Due to the possible adverse effects on the bone produced by inhaled glucocorticoids in postmenopausal women, we also included diagnoses for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, ICD-10 codes J41, J42, J43 and J44); and asthma (J45).

- •

Prescription drug-related variables: the active prescription database in the primary care medical records system includes the drugs dispensed by community pharmacies, thus excluding drugs dispensed in hospitals or by hospital pharmacy services. Drugs were classified according to the Anatomical, Therapeutic, Chemical (ATC) Classification System. We analyzed bisphosphonates (ATC codes M05BA, except zolendronic acid, a drug for hospital use [ATC M05BA08] and M05BB as well as aromatase inhibitors, ATC code L02BG), linked to an increased risk of frailty fractures and associated with secondary osteoporosis.

Patients’ demographic and clinical profile was analyzed using descriptive statistics. The comparative analysis was made between the group of women who discontinued versus the group of women who continued bisphosphonate treatment. The cumulative incidence of fractures and incidence density were calculated, and logistic regression analysis was used to determine the association of each variable with the fracture event (vertebral, hip/femur, and total fractures). Cox models were applied to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) and its confidence interval (CI), which showed the strength of the association of each variable analyzed with the appearance of the event over time.

All analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical package for Windows, version 25 (SPSS Inc., New York, IL, USA). The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Ethical aspectsThe variables collected from the electronic medical record were linked to a unique and anonymous personal identifier, thus guaranteeing the confidentiality of the patients in accordance with the provisions of Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on personal data protection and guarantee of digital rights and Regulation (EU) 2016/679 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data.

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Foundation University Institute for Primary Health Care Research Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAPJGol) (Protocol no: CEI: 21/248-P).

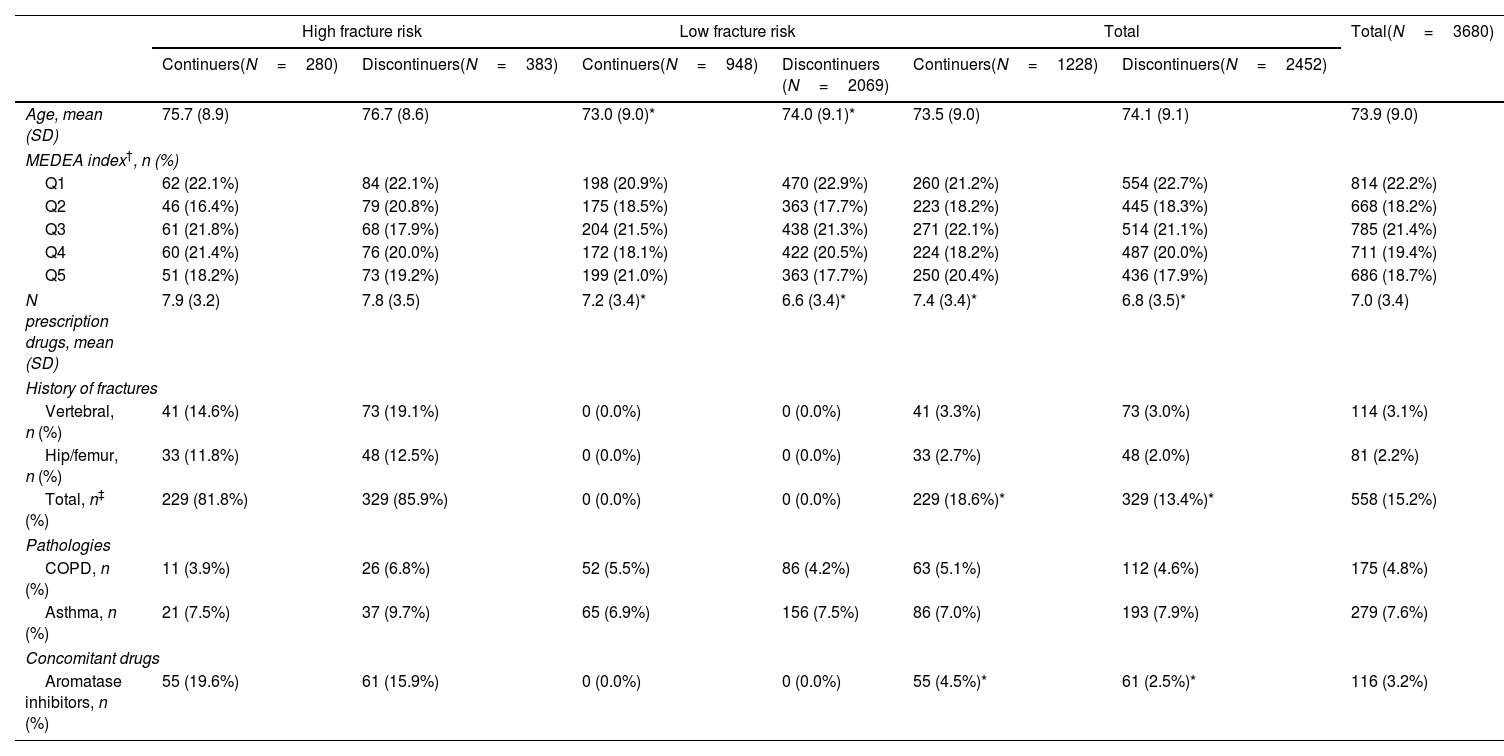

ResultsThe analysis included 3680 women, with a mean age of 74 years (standard deviation [SD] 9.0). Most were polymedicated (mean 7 prescribed drugs [SD 3.4] per patient), and 15.2% had a history of osteoporotic fracture in the previous five years. Table 2 presents the patient characteristics, stratified according to fracture risk and the continuity/deprescription of treatment with bisphosphonates.

Baseline characteristics in women treated with bisphosphonates for at least five years (N=3680).

| High fracture risk | Low fracture risk | Total | Total(N=3680) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuers(N=280) | Discontinuers(N=383) | Continuers(N=948) | Discontinuers (N=2069) | Continuers(N=1228) | Discontinuers(N=2452) | ||

| Age, mean (SD) | 75.7 (8.9) | 76.7 (8.6) | 73.0 (9.0)* | 74.0 (9.1)* | 73.5 (9.0) | 74.1 (9.1) | 73.9 (9.0) |

| MEDEA index†, n (%) | |||||||

| Q1 | 62 (22.1%) | 84 (22.1%) | 198 (20.9%) | 470 (22.9%) | 260 (21.2%) | 554 (22.7%) | 814 (22.2%) |

| Q2 | 46 (16.4%) | 79 (20.8%) | 175 (18.5%) | 363 (17.7%) | 223 (18.2%) | 445 (18.3%) | 668 (18.2%) |

| Q3 | 61 (21.8%) | 68 (17.9%) | 204 (21.5%) | 438 (21.3%) | 271 (22.1%) | 514 (21.1%) | 785 (21.4%) |

| Q4 | 60 (21.4%) | 76 (20.0%) | 172 (18.1%) | 422 (20.5%) | 224 (18.2%) | 487 (20.0%) | 711 (19.4%) |

| Q5 | 51 (18.2%) | 73 (19.2%) | 199 (21.0%) | 363 (17.7%) | 250 (20.4%) | 436 (17.9%) | 686 (18.7%) |

| N prescription drugs, mean (SD) | 7.9 (3.2) | 7.8 (3.5) | 7.2 (3.4)* | 6.6 (3.4)* | 7.4 (3.4)* | 6.8 (3.5)* | 7.0 (3.4) |

| History of fractures | |||||||

| Vertebral, n (%) | 41 (14.6%) | 73 (19.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 41 (3.3%) | 73 (3.0%) | 114 (3.1%) |

| Hip/femur, n (%) | 33 (11.8%) | 48 (12.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 33 (2.7%) | 48 (2.0%) | 81 (2.2%) |

| Total, n‡ (%) | 229 (81.8%) | 329 (85.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 229 (18.6%)* | 329 (13.4%)* | 558 (15.2%) |

| Pathologies | |||||||

| COPD, n (%) | 11 (3.9%) | 26 (6.8%) | 52 (5.5%) | 86 (4.2%) | 63 (5.1%) | 112 (4.6%) | 175 (4.8%) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 21 (7.5%) | 37 (9.7%) | 65 (6.9%) | 156 (7.5%) | 86 (7.0%) | 193 (7.9%) | 279 (7.6%) |

| Concomitant drugs | |||||||

| Aromatase inhibitors, n (%) | 55 (19.6%) | 61 (15.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 55 (4.5%)* | 61 (2.5%)* | 116 (3.2%) |

SD: standard deviation; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The mean number of days in treatment with bisphosphonates throughout the follow-up period was 288.2 days per year (95% CI 284.9–291.6) among women who were continuing treatment and 68.8 (95% CI 63.2–74.3) in those who discontinued it (Supplementary Table 2).

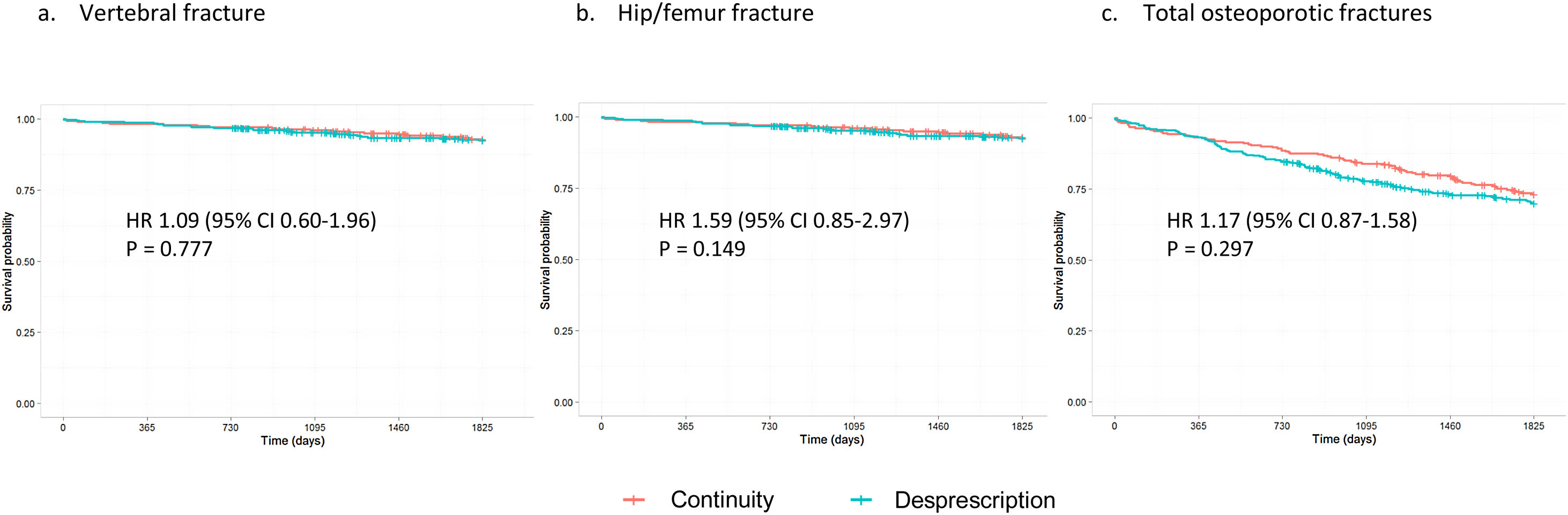

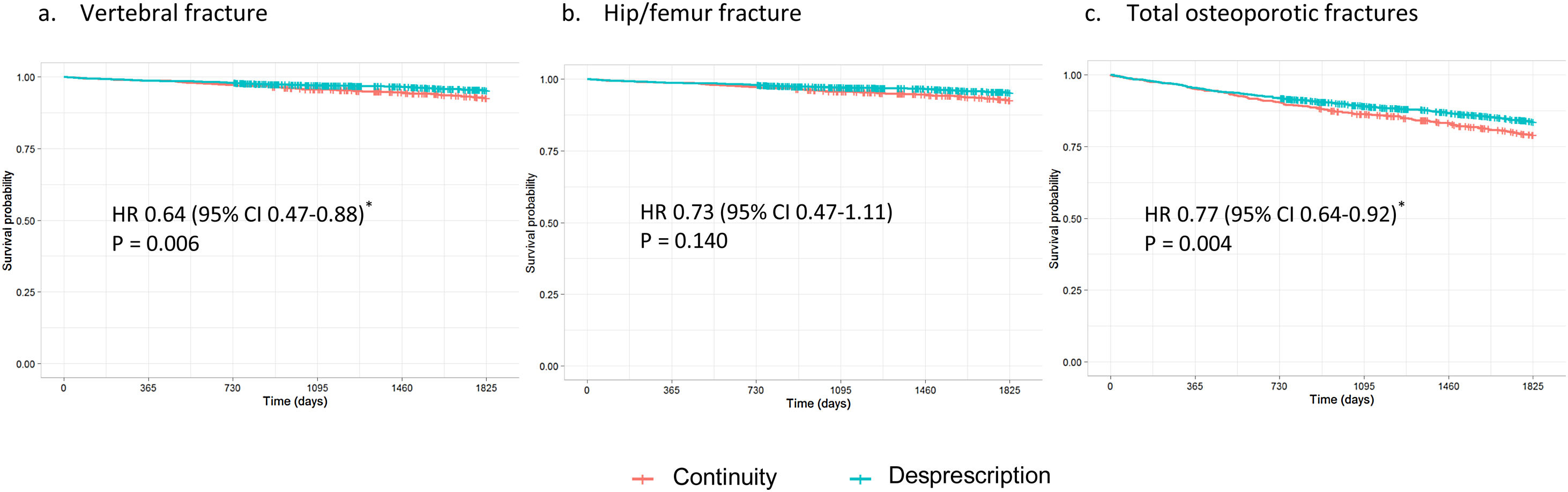

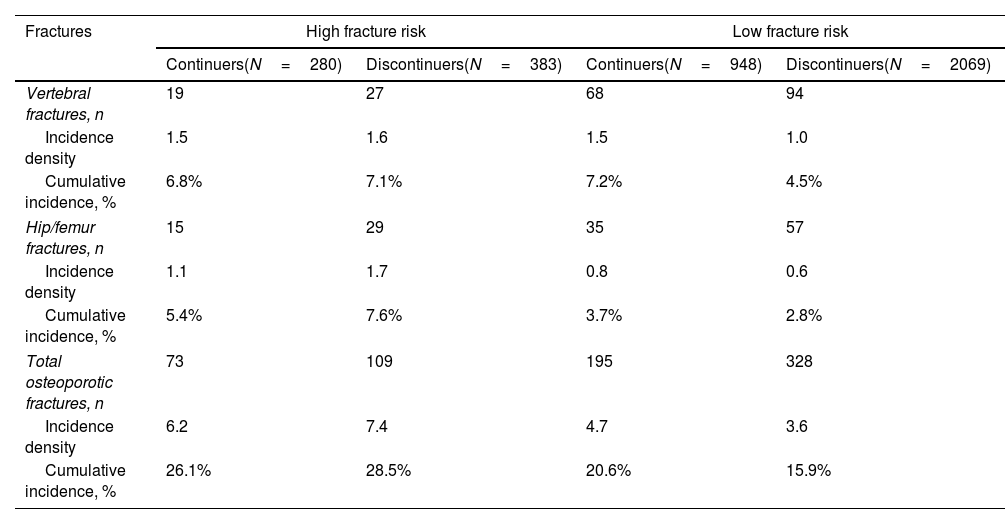

Table 3 shows the cumulative incidence and incidence density for vertebral, hip/femur fractures and total osteoporotic fractures, regardless of location. High-risk patients who were deprescribed bisphosphonate had a higher incidence of fracture compared to those who continued the treatment, although these differences were not significant (HR 1.17, 95% CI 0.87–1.58 for total fractures, Fig. 1). In contrast, low-risk women who continued the treatment showed a higher incidence of fracture than those in whom it was deprescribed (Fig. 2). This difference was significant for vertebral fractures (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47–0.88) and total fractures (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.64–0.92).

Incidence of new fractures in women treated with biphosphonates for at least five years (N=3680).

| Fractures | High fracture risk | Low fracture risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuers(N=280) | Discontinuers(N=383) | Continuers(N=948) | Discontinuers(N=2069) | |

| Vertebral fractures, n | 19 | 27 | 68 | 94 |

| Incidence density | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| Cumulative incidence, % | 6.8% | 7.1% | 7.2% | 4.5% |

| Hip/femur fractures, n | 15 | 29 | 35 | 57 |

| Incidence density | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Cumulative incidence, % | 5.4% | 7.6% | 3.7% | 2.8% |

| Total osteoporotic fractures, n | 73 | 109 | 195 | 328 |

| Incidence density | 6.2 | 7.4 | 4.7 | 3.6 |

| Cumulative incidence, % | 26.1% | 28.5% | 20.6% | 15.9% |

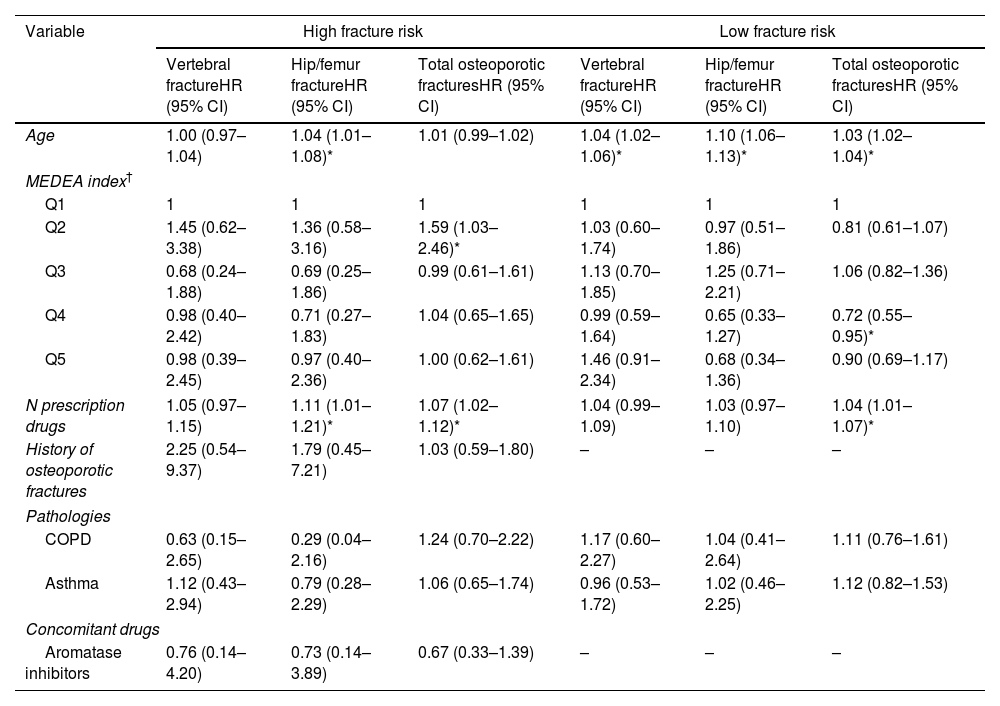

Table 4 shows the multivariable Cox analysis, adjusting for all included variables. The risk of total fractures increased with age in the low-risk group (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04). In both low- and high-risk groups, a greater number of medications was associated with an increased risk of total fractures. A history of fracture, respiratory disease (asthma and COPD), and treatment with aromatase inhibitors were not significantly associated with risk of fracture in the multivariate analysis.

Multivariate analysis of the risk of new fractures in women treated with biphosphonates for at least five years, by clinical and sociodemographic variables (N=3680).

| Variable | High fracture risk | Low fracture risk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral fractureHR (95% CI) | Hip/femur fractureHR (95% CI) | Total osteoporotic fracturesHR (95% CI) | Vertebral fractureHR (95% CI) | Hip/femur fractureHR (95% CI) | Total osteoporotic fracturesHR (95% CI) | |

| Age | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08)* | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06)* | 1.10 (1.06–1.13)* | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)* |

| MEDEA index† | ||||||

| Q1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Q2 | 1.45 (0.62–3.38) | 1.36 (0.58–3.16) | 1.59 (1.03–2.46)* | 1.03 (0.60–1.74) | 0.97 (0.51–1.86) | 0.81 (0.61–1.07) |

| Q3 | 0.68 (0.24–1.88) | 0.69 (0.25–1.86) | 0.99 (0.61–1.61) | 1.13 (0.70–1.85) | 1.25 (0.71–2.21) | 1.06 (0.82–1.36) |

| Q4 | 0.98 (0.40–2.42) | 0.71 (0.27–1.83) | 1.04 (0.65–1.65) | 0.99 (0.59–1.64) | 0.65 (0.33–1.27) | 0.72 (0.55–0.95)* |

| Q5 | 0.98 (0.39–2.45) | 0.97 (0.40–2.36) | 1.00 (0.62–1.61) | 1.46 (0.91–2.34) | 0.68 (0.34–1.36) | 0.90 (0.69–1.17) |

| N prescription drugs | 1.05 (0.97–1.15) | 1.11 (1.01–1.21)* | 1.07 (1.02–1.12)* | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07)* |

| History of osteoporotic fractures | 2.25 (0.54–9.37) | 1.79 (0.45–7.21) | 1.03 (0.59–1.80) | – | – | – |

| Pathologies | ||||||

| COPD | 0.63 (0.15–2.65) | 0.29 (0.04–2.16) | 1.24 (0.70–2.22) | 1.17 (0.60–2.27) | 1.04 (0.41–2.64) | 1.11 (0.76–1.61) |

| Asthma | 1.12 (0.43–2.94) | 0.79 (0.28–2.29) | 1.06 (0.65–1.74) | 0.96 (0.53–1.72) | 1.02 (0.46–2.25) | 1.12 (0.82–1.53) |

| Concomitant drugs | ||||||

| Aromatase inhibitors | 0.76 (0.14–4.20) | 0.73 (0.14–3.89) | 0.67 (0.33–1.39) | – | – | – |

CI: confidence interval; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR: hazard ratio.

Our results suggest that deprescribing bisphosphonates in women who have already received five years of treatment does not increase the risk of developing new fractures. Indeed, in low-risk women, continuing this treatment might could even favor the appearance of new osteoporotic and vertebral fractures. Other factors associated with an increased risk of fracture include advanced age and polypharmacy.

Comparison with existing literatureThese results are in line with the recommendations of large scientific societies to periodically reassess the need for continuing bisphosphonate treatment after five years.3,14,21 However, there is still little evidence to elucidate the optimal duration of treatment and the length of its suspension.

Studies of bisphosphonate have not demonstrated long-term efficacy for preventing hip fractures or non-vertebral fractures, and results have been contradictory for clinical vertebral fractures.10,11,22 Moreover, there are few observational and real-world data studies assessing the impact of bisphosphonate deprescription in terms of fracture, and their results are inconsistent.23–25

Our results are in line with those from other recent cohort studies, which have also failed to find an increased risk of fracture (vertebral fracture, hip fracture or any osteoporotic fracture) in women who take therapeutic holidays after two to three years of treatment with bisphosphonates.23,24 Adams et al. assessed the risk of fracture at one year from the therapeutic vacation; the authors did not observe any benefit associated with continuing bisphosphonates, whether in women with or without a history of fracture. Similarly to our findings, they also saw a reduction in the risk of vertebral fracture associated with bisphosphonate discontinuation among women with no history of fracture.23 In another cohort study, this time in women with a history of fracture who had received at least two years of bisphosphonates, the authors likewise reported no differences in the risk of vertebral or hip fractures in patients who discontinued bisphosphonate treatment after 2 years compared with those who continued it for 10–13 years.24

Our results are also consistent with those from different systematic reviews, which question the real efficacy of bisphosphonates in women at low risk of fracture.4–6 However, they differ from those reported by other authors, such as Curtis et al., who observed an increased risk of fracture associated with discontinuing alendronate for more than two years, although without differentiating between women at high versus low risk.25

Strengths and limitationsThis study draws data from a large database of real-world medical records pertaining to women previously exposed to long-term bisphosphonate treatment and attended in primary care. The large number of women analyzed makes it a representative cohort of women taking bisphosphonates in Catalonia. Likewise, the five-year follow-up period makes it possible to assess, with a certain degree of certainty, the impact of the intervention on the appearance of new fractures.

Retrospective cohort studies using population-based databases allow the study of a large number of patients and facilitate the timely attainment of results. On the other hand, underreporting by health professionals may lead to inaccuracies in the medical record. In addition, the variables related to the treatments are extracted from the electronic prescription database, precluding the assessment of therapeutic adherence. Furthermore, our database does not include zolendronic acid, commonly used in Spanish hospitals, so there is a risk of misclassification bias in the women included in the deprescription group. There are also different tools for predicting the risk of fracture according to other associated variables (e.g. bone mineral density, tobacco, alcohol), which were not contemplated in our study; however, recent reviews have concluded that the presence of the criteria used (advanced age, female sex, and history of fracture) are independently associated with an increased risk of fracture, regardless of other diagnostic criteria.26 In our study, treatment with calcium and/or vitamin D supplements has not been considered as a variable, due to the difficulty that exists in the studies based on real-world data to know the calcium and/or vitamin D supplementation done through diet and/or supplementation. On the other hand, in prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of supplementation have not shown a benefit on fracture rates. Furthermore, we measured the exposure to glucocorticoids indirectly, according to the diagnosis of the most prevalent pathologies in primary care that are characterized by frequent chronic use of glucocorticoids. This decision was due to the complexity involved in quantifying the exposure time to glucocorticoids that is associated with an increased risk of fracture in terms of dose and duration of treatment.

Finally, in our study, treatment continuity was defined based on the fulfillment of two criteria: annual exposure, by which women had to be treated with bisphosphonate for at least five consecutive months, and exposure during follow-up, by which the women had to have been prescribed bisphosphonate for at least 60% of the time. Regarding the annual exposure criterion, despite having established a minimum cutoff of five months, most of the women in the continuation group were prescribed bisphosphonate for more than six months of the year. These data are supported by different studies23,27–29 assessing the risk of fracture in relation to the duration of exposure to bisphosphonate, which is considered effective if taken 50–80% of the time. However, there is no consensus on the methodology to assess the exposure time or the cutoff values to be used, and the literature uses heterogeneous criteria.23,27–30 Furthermore, in the specific case of bisphosphonates, their effect lasts for years after they are withdrawn,2 so the patient continues to perceive a benefit even after they stop taking them.

Implications for research and/or practiceOur results suggest that deprescribing bisphosphonates in women who have already received five years of treatment does not increase fracture risk, calling into question whether the high number of women at low risk of fracture in our area benefit from prolonged bisphosphonate treatment. It would be interesting to further understand the advantages of extending treatment based on fracture risk stratification. In addition, this study manifests the role of the real world data in the risk benefit assessment in primary care patients.

- •

Even though bisphosphonates demonstrated efficacy in preventing fractures in women with osteoporosis, there is debate about which population subgroup could benefit from this treatment.

- •

Few studies have assessed the long-term efficacy of bisphosphonates for reducing fracture risk.

- •

The long follow-up period allows us to assess, with a certain degree of certainty, the impact of the intervention on new fractures in women being treated with bisphosphonates.

- •

Bisphosphonates desprescription in women at low risk of fractures has been associated with a decreased risk of vertebral and total fractures.

- •

Bisphosphonates desprescription in women at high fracture risk has not been associated with an increased risk of fracture.

This study protocol (Protocol no: CEI: 21/248-P) was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Foundation University Institute for Primary Health Care Research Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAPJGol).

FundingThe authors have declared no funding specifically requested for this project.

Competing interestsThe authors have declared no competing interests.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jordi Real B.Sc. for his contributions to the statistical analysis and Meggan Harris for her support with the English translation.