To analyze the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on serum glucose levels of pregnant women.

DesignA retrospective analysis of O'Sullivan test in pregnant women who underwent COVID-19 lockdown compared to controls.

SitePoniente Primary Health Care center in Córdoba (Spain).

Participants235 pregnant women from 23+0 to 25+0 weeks of gestation without diabetes mellitus.

InterventionsGestational diabetes mellitus screening with O'Sullivan test and 3-h oral glucose tolerance test.

Main measurementsPregnant women who underwent gestational diabetes mellitus screening with O'Sullivan test before (control group) and during COVID-19 Lockdown (Lockdown group) in Córdoba (Spain) were investigated. Lockdown group was divided in early and late lockdown. An additional, control group from data of the same months of the Lockdown in the previous year were recorded to discarded seasonally (adjusted seasonally control) this group was also divided in early and late seasonally adjusted.

A logistic regression model for O'Sullivan test has been performed to analyze potential cofounders. Kolgomorov–Smirnov and Kruskal–Wallis test comparing pregnant women who underwent COVID-19 lockdown with the two types of controls.

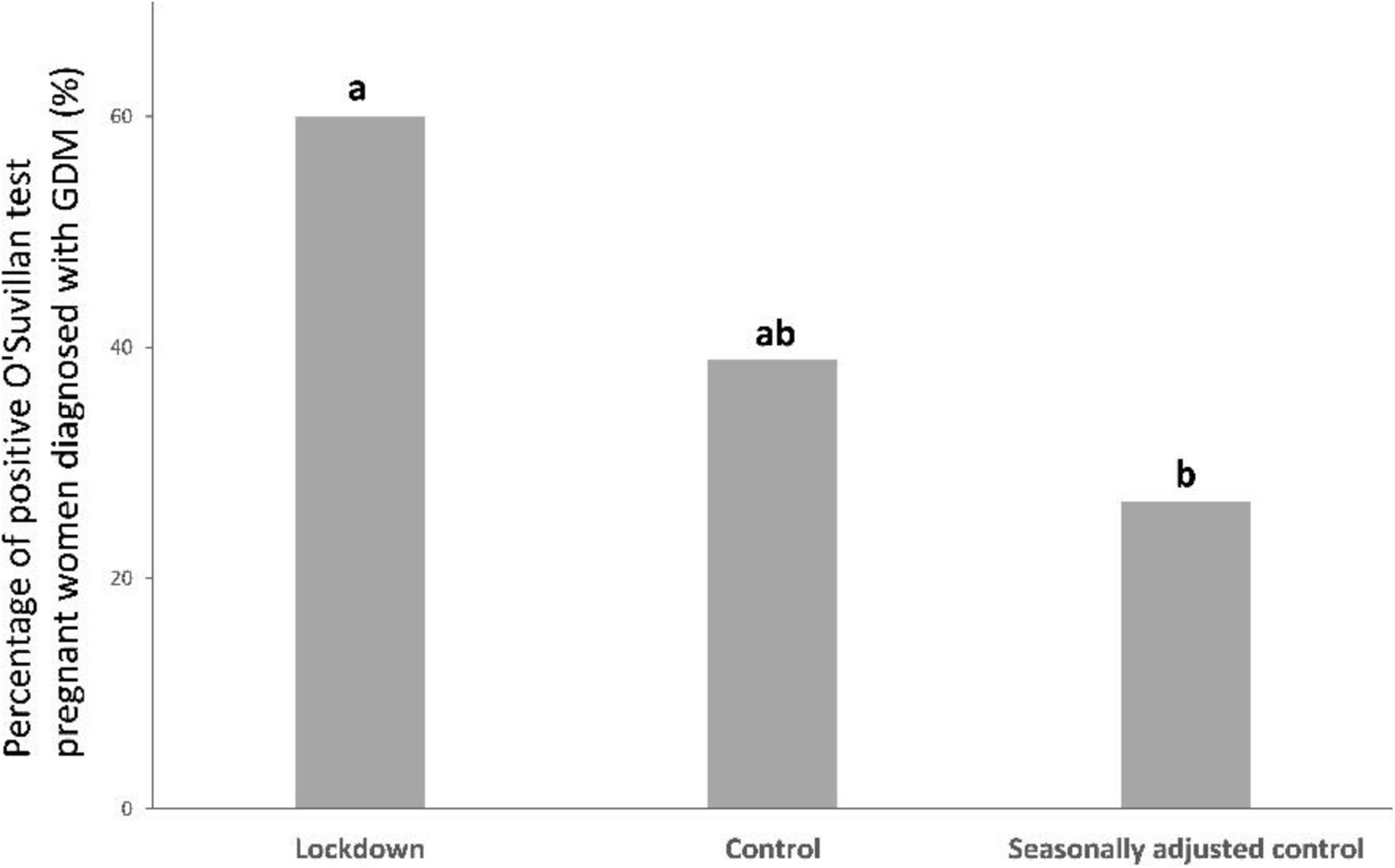

ResultsStatistically significant differences were found in serum glucose after O'Sullivan test between lockdown group and control group (123.51±26.02mg/dL and 112.86±31.28mg/dL; p=0.017). When early lockdown group and control group were compared no differences were found (119.64±26.18mg/dL vs. 112.86±31.28mg/dL; p>0.05) whereas differences were observed in late lockdown group and control group (127.22±25.59mg/dL vs. 112.86±31.28mg/dL; p=0.009). Statistical trends were also found between lockdown group and seasonally adjusted group and between lockdown and late seasonally adjusted group (p=0.089). A higher proportion of positive O'Suvillan pregnant women who were subsequently diagnosed with GDM were found in lockdown group compared to the seasonally adjusted control group (60% vs. 26.06% respectively; p<0.05).

ConclusionsThe COVID-19 lockdown was associated with an increase in serum glucose levels after the O'Sullivan test as well as a higher GDM diagnosis risk in pregnant women. The findings of our study emphasize the essential requirement for comprehensive maternal services and the accessibility to community's health assets during future lockdown scenarios to pregnant women.

Analizar el impacto del confinamiento por el COVID-19 en el nivel de glucosa sérica en mujeres gestantes.

DiseñoAnálisis retrospectivo del test de O'Sullivan en embarazadas sometidas a confinamiento debido al COVID-19 comparadas con controles.

SitioCentro de Salud de Poniente, Córdoba (España).

ParticipantesUn total de 235 embarazadas de 23+0 a 25+0 semanas de gestación sin diabetes mellitus.

IntervencionesCribado de la diabetes mellitus gestacional con el test de O'Sullivan y prueba de tolerancia oral a la glucosa.

Mediciones principalesSe investigó a las mujeres embarazadas que se sometieron al cribado de diabetes mellitus gestacional con el test de O'Sullivan antes (grupo control) y durante el confinamiento por el COVID-19 (grupo confinado) en Córdoba (España). El grupo confinado se dividió en confinamiento temprano y tardío. Un grupo de control adicional con los datos de los mismos meses de confinamiento, pero en el año anterior, se registró para descartar estacionalidad (control ajustado estacionalmente); este grupo también se dividió en temprano y tardío. Se ha realizado un modelo de regresión logística para el test de O'Sullivan para analizar los posibles cofundadores. Las pruebas de Kolgomorov-Smirnov y Kruskal-Wallis se utilizaron para comparar a las mujeres embarazadas que se sometieron a confinamiento por el COVID-19 con los dos tipos de controles.

ResultadosSe encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la glucosa sérica tras la prueba de O'Sullivan entre el grupo confinado y el grupo control (123,51±26,02mg/dL y 112,86±31,28mg/dL; p=0,017). Cuando se compararon el grupo de confinamiento temprano y el grupo de control no se hallaron diferencias (119,64±26,18mg/dL frente a 112,86±31,28mg/dL; p>0,05), mientras que sí se observaron diferencias en el grupo de confinamiento tardío y el grupo de control (127,22±25,59mg/dL frente a 112,86±31,28mg/dL; p=0,009). También se encontraron tendencias estadísticas entre el grupo confinado y el grupo desestacionalizado y entre el grupo confinado y el grupo desestacionalizado tardío (p=0,089). La proporción de embarazadas positivas al test de O'Suvillan a las que posteriormente se diagnosticó diabetes mellitus gestacional en el grupo de confinamiento fue mayor que el grupo de control desestacionalizado (60% frente a 26,06%, respectivamente; p<0,05).

ConclusionesEl confinamiento por el COVID-19 se asoció con un aumento de la glucosa sérica tras la prueba de O'Sullivan, así como un mayor riesgo de diagnóstico de diabetes mellitus gestacional en las mujeres embarazadas. Los hallazgos de nuestro estudio enfatizan la necesidad de servicios maternos integrales y el acceso a los activos para la salud de la comunidad durante futuros escenarios de confinamiento a mujeres gestantes.

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a temporary elevation in serum glucose levels due to glucose intolerance that occurs for the first time or is initially diagnosed during pregnancy.1 It is a prevalent complication among pregnant women and is observed globally.2 The regional standardized prevalence of GDM in Europe is 7.8%2 and in Spain is 5.3%.3 While the magnitude of blood glucose elevation in GDM is typically not as pronounced as that in diabetes mellitus, it can still pose substantial risks to both expectant mothers and their fetuses.3,4 Short-term consequences of GDM for mothers and infants encompass heightened maternal pregnancy complications, including gestational hypertension and polyhydramnios, along with an increased likelihood of fetal macrosomia and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome.4 Furthermore, the long-term health concern for both mothers and offspring primarily revolves around the elevated risk of developing long-term type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in the postpartum period.2,4 Consequently, reducing the prevalence of GDM stands as a significant and pressing public health imperative.2,5

GDM diagnosis was established in accordance with the two-step diagnostic approach outlined in the national guidelines.5–8 First, it was conducted a universal screening for GDM using the O'Sullivan test, which not involved fasting and the consumption of 50g of glucose, for all pregnant women who did not have preexisting diabetes mellitus before pregnancy. The O'Sullivan test was considered positive when the glucose level measured equaled or exceeded 140mg/dL. Subsequently, a 100-g glucose tolerance test have to be performed (involve fasting) in order determine the diagnosis.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 has posed a significant challenge to the global perspective on public health and vulnerable populations, including pregnant women. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments and healthcare authorities worldwide have implemented a range of extraordinary measures aimed at mitigating the spread of the virus. To curb the transmission of the virus and prevent overwhelming the healthcare system, the Spanish government, on March 14th, issued an executive order to declare a state of emergency.9 This directive marked the commencement of stringent lockdown measures, including social distancing and mandatory home confinement.9 The lockdown concluded on June 21st, following a phased de-escalation of lockdown measures that commenced on May 11th. This initial phase allowed pregnant women to venture outside for a one-hour daily walk and exercise routine during specified time windows.9 Several epidemiological studies have documented notable associations between COVID-19 lockdown measures and maternal well-being and pregnancy outcomes, including incidents of stillbirth and preterm birth.10 However, despite being a common pregnancy complication, there has been a limited exploration of the correlation between COVID-19 lockdown measures and GDM11,12 and blood sugar regulation in pregnant women.10 Furthermore, there are several unresolved research questions and constraints that warrant thorough investigation in future studies. First, prior research has predominantly focused on alterations in glycemic control among GDM patients, necessitating a deeper examination of shifts in GDM prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, the impact of environmental changes on maternal health is intricately linked to the gestational stage.13 The critical window of exposure during which COVID-19 influences the occurrence of GDM in pregnant women remains indeterminate. Third, the constantly fluctuating intensity and duration of lockdown measures in the different countries must be considered when assessing their impact on O'Sullivan test and GDM. Finally, health determinants are different worldwide and also different in the same country or community, so the study must take into account such circumstances. That is the case of Spain in which any study has analyzed the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on the results of the screening and diagnosis of GDM.

In an effort to address these research voids, we conducted a thorough examination of the connection between COVID-19 lockdown measures and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus measured by O'Sullivan test and its final diagnosis of woman with GDM. This examination involved a comprehensive assessment of the duration and intensity of exposure experienced by pregnant women in Spain. Additionally, we took into account seasonal variations and ensured an adequate follow-up period in our study. Therefore, the aim of this study was evaluated the impact COVID-19 lockdown on the O'Sullivan test results and GDM of pregnant women.

Material and methodsA retrospective case–control study in Poniente Primary Health Care center in Córdoba (Spain) was conducted. O'Sullivan test performed to pregnant women underwent COVID-19 lockdown from April 2020 to September 2020 (Lockdown group) were compared to Controls that were recorded from April 2019 to March 2020 (Control groups).

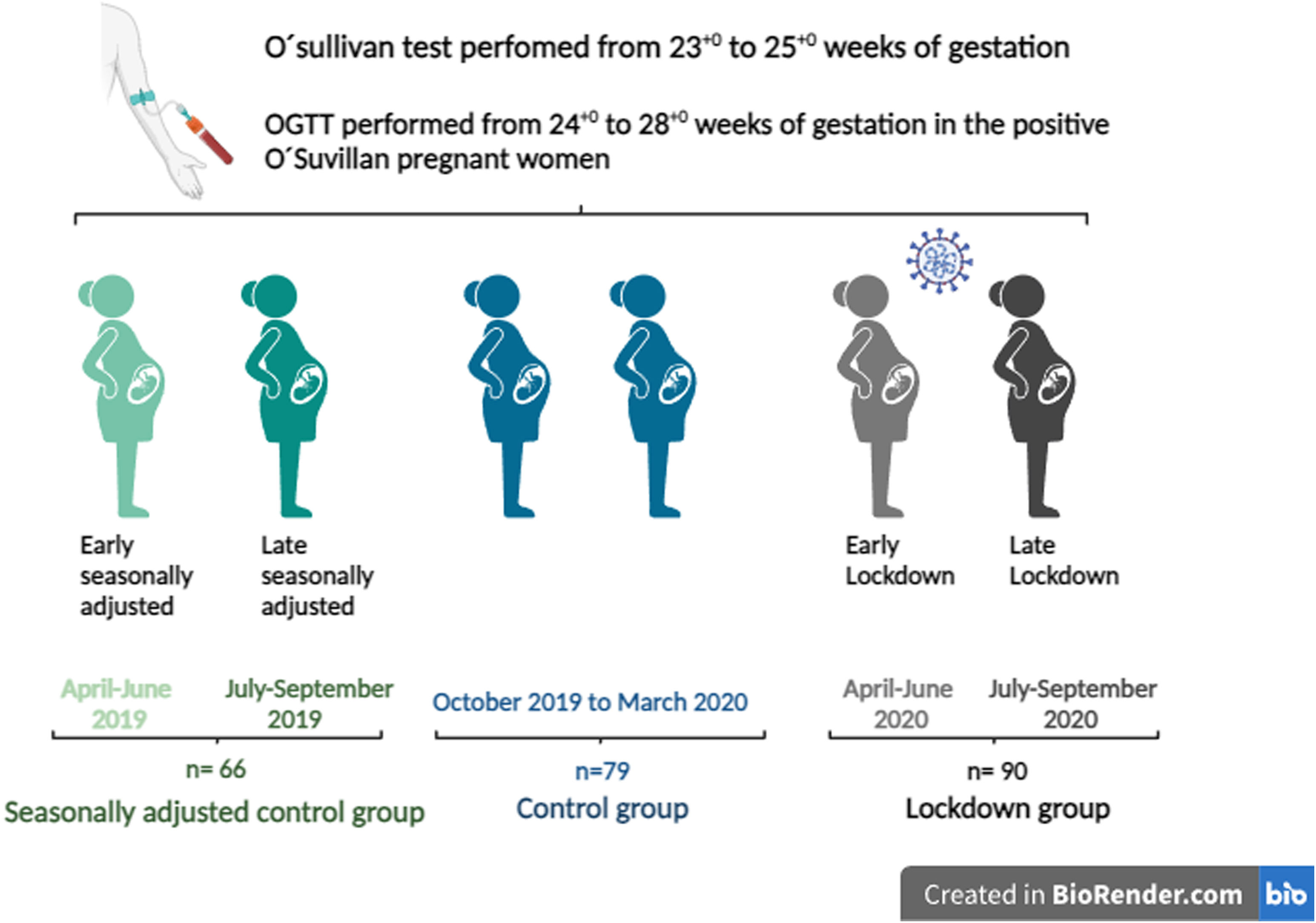

In order to investigate the potential impact of mandatory home confinement on the O'Sullivan test and diagnosis of GDM, the lockdown group (O'Sullivan test performed from April to September 2020) were divided in: early lockdown (O'Sullivan test performed from April to June 2020) and late lockdown (from July to September 2020). This late lockdown group was not in confinement at the moment of the test but suffered the lockdown been pregnant. Control group was divided in: seasonally unadjusted control from October 2019 to March 2020 (months after the lockdown, control group), and seasonally adjusted control group from April 2019 to September 2019 (same months of the lockdown but in the previous year). This group was also subdivided in: early control from April 2019 to June 2019 and late control from July 2019 to September 2019 (Fig. 1).

Scheme of the study design. O'sullivan test was performed in each pregnant woman from 23+0 to 25+0 weeks of gestation. OGTT was performed from 24+0 to 28+0 weeks of gestation in women who were positive to O'Suvillan test. Lockdown group are represented with back pregnant women. Light back woman represents early lockdown (April–June 2020) and dark back woman represents late lockdown. Control group (October 2019–March 2020) are represented with women in blue. Seasonally adjusted control group are represented with green women. Light green represents early seasonally adjusted group (April 2019–June 2019) and dark green represents late seasonally adjusted group (July 2019–September 2019). The figure was created by biorender®.

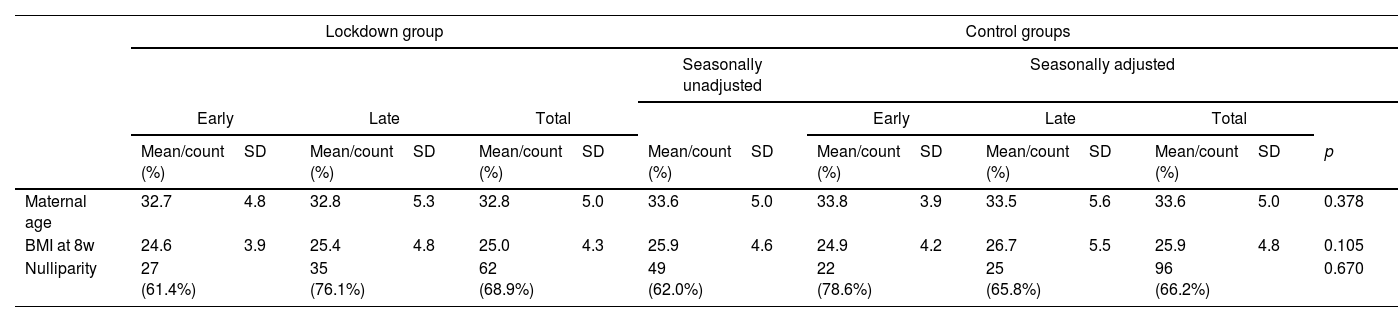

The inclusion criteria included: maternal age above 18 years old, pregnant women followed up in Poniente Primary Health Care center in Córdoba (Spain) without pregestational DM, O'Sullivan test performed. We extracted the following individual information from medical records: maternal age, parity, Body Mass Index (BMI) at 8 weeks (wk) of gestation, BMI at 24 wks of gestation, the increment of BMI and O'Sullivan test in current pregnancy. All the groups were comparable in terms of maternal age, BMI at 8w, nulliparity (Table 1). With regard to housing, the majority of the women in this study resided in apartments in an urban area. The mean per capita income in the province of Córdoba was 11,791 euros (€) in 2020 whereas the mean in the country (Spain) was 12,292€. The mean per capita income in the neighborhoods studied was 14,941€.14

Characteristics of pregnant women in the different groups.

| Lockdown group | Control groups | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seasonally unadjusted | Seasonally adjusted | ||||||||||||||

| Early | Late | Total | Early | Late | Total | ||||||||||

| Mean/count (%) | SD | Mean/count (%) | SD | Mean/count (%) | SD | Mean/count (%) | SD | Mean/count (%) | SD | Mean/count (%) | SD | Mean/count (%) | SD | p | |

| Maternal age | 32.7 | 4.8 | 32.8 | 5.3 | 32.8 | 5.0 | 33.6 | 5.0 | 33.8 | 3.9 | 33.5 | 5.6 | 33.6 | 5.0 | 0.378 |

| BMI at 8w | 24.6 | 3.9 | 25.4 | 4.8 | 25.0 | 4.3 | 25.9 | 4.6 | 24.9 | 4.2 | 26.7 | 5.5 | 25.9 | 4.8 | 0.105 |

| Nulliparity | 27 (61.4%) | 35 (76.1%) | 62 (68.9%) | 49 (62.0%) | 22 (78.6%) | 25 (65.8%) | 96 (66.2%) | 0.670 | |||||||

p-Value reported of comparison between total lockdown group and control groups. BMI: body mass index.

The gynecologist, and especially the midwife, within the primary care team were the health care providers responsible for managing low-risk pregnancies.15 In-person consultations were conducted for diagnostic purposes, including sample collection, and to formulate general hygienic-dietary recommendations. However, the results of the analyses and the hygienic-dietary recommendations derived from them were transmitted via telematics. A universal screening for GDM using the O'Sullivan test, were performed from 23+0 to 25+0 weeks of gestation.5 This screening involves the consumption of 50g of glucose for all pregnant women who did not have preexisting diabetes mellitus before pregnancy. The test does not require fasting. The determination of glycemia in blood sample was performed 60min after the drank of the glucose. The O'Sullivan test is considered positive when the measured glucose level equals or exceeds 140mg/dL. An oral 100-g glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed from 24+0 to 28+0 weeks of gestation in the positive O'Suvillan pregnant women (involving fasting). Confirmation of GDM occurred when two or more of the following points were abnormal: glucose level in fasting ≥105mg/dL, when 1-h post consumption the glucose level is ≥190mg/dL, when two hours post consumption the glucose is ≥165mg/dL, and finally when three hours post consumption the level is ≥145mg/dL.

Taking into consideration biological plausibility, a review of the existing literature, and data accessibility, maternal age, parity, and BMI were investigated as potential confounding factors associated with GDM.

A descriptive analysis of all the variables analyzed was performed. Normality and homoscedasticity were assessed for all continuous variables with Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene test, respectively. Proportions were compared using Pearson's Chi-squared test and Fisher correction when applied. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and Pearson's Chi-squared test were used to compare the characteristics of each group. Outcome variable was O'Sullivan test. It was considered as continuous (glucose level one hour after 50g of glucose consumption) and categorical (positive/negative). Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Kruskal–Wallis test for comparing continuous outcome was performed. To assess the relationship between lockdown, potential cofounders (maternal age, parity and BMI) and O'Sullivan test, a logistic regression analysis was performed. The reported results include odds ratios or estimates, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values. The correlation between the lockdown duration in months and the results of O'sullivan test (mg/dL) was assessed by Pearson's correlation. All tests were two-tailed and the level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Statistical trends were considered at <0.09. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) and STATA BE-Basic Edition version 18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

ResultsData from 235 pregnant women matched the inclusion criteria for the study, 90 of them were recruited in the lockdown group whereas 145 pregnant women were defined as controls. In the lockdown group 44 (48.9%) pregnant women were selected in early lockdown group and 46 (51.1%) in late lockdown group. From the 145 women included in control group 79 (54.5%) came from the seasonally unadjusted control group (control group) and 66 from seasonally adjusted. This group was also divided in 28 (19.3%) pregnant women from early control, 38 (26.2%) from late control.

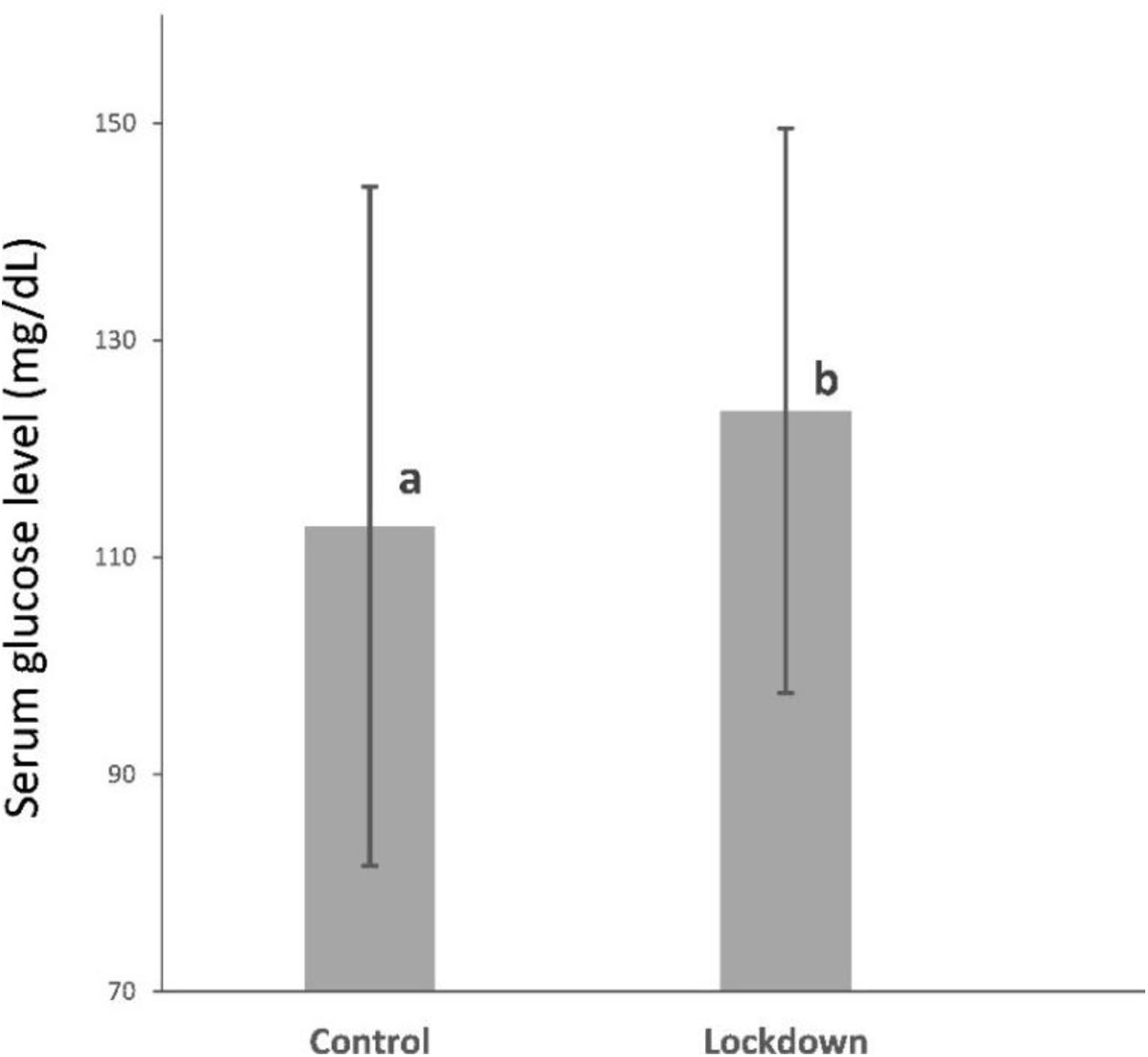

Mean of serum glucose after O'Sullivan test was 123.51±26.02mg/dL and it was above 140mg/dL in 20 (22.22%) pregnant women in lockdown group. Mean of serum glucose after O'Sullivan test was 112.86±31.28mg/dL and it was above 140mg/dL in 18 (22.8%) pregnant women in control group. The lockdown group showed a 9.43% increase in serum glucose levels (10.65mg/dL) compared to the control group. Statistically significant differences were found in serum glucose after O'Sullivan test between lockdown group and control group (123.51±26.02mg/dL and 112.86±31.28mg/dL; p=0.017) Fig. 2. However, no differences were found in O'Sullivan pathological test (glucose above 140mg/dL) between lockdown and control group (22.2% vs. 22.8%; p=0.924).

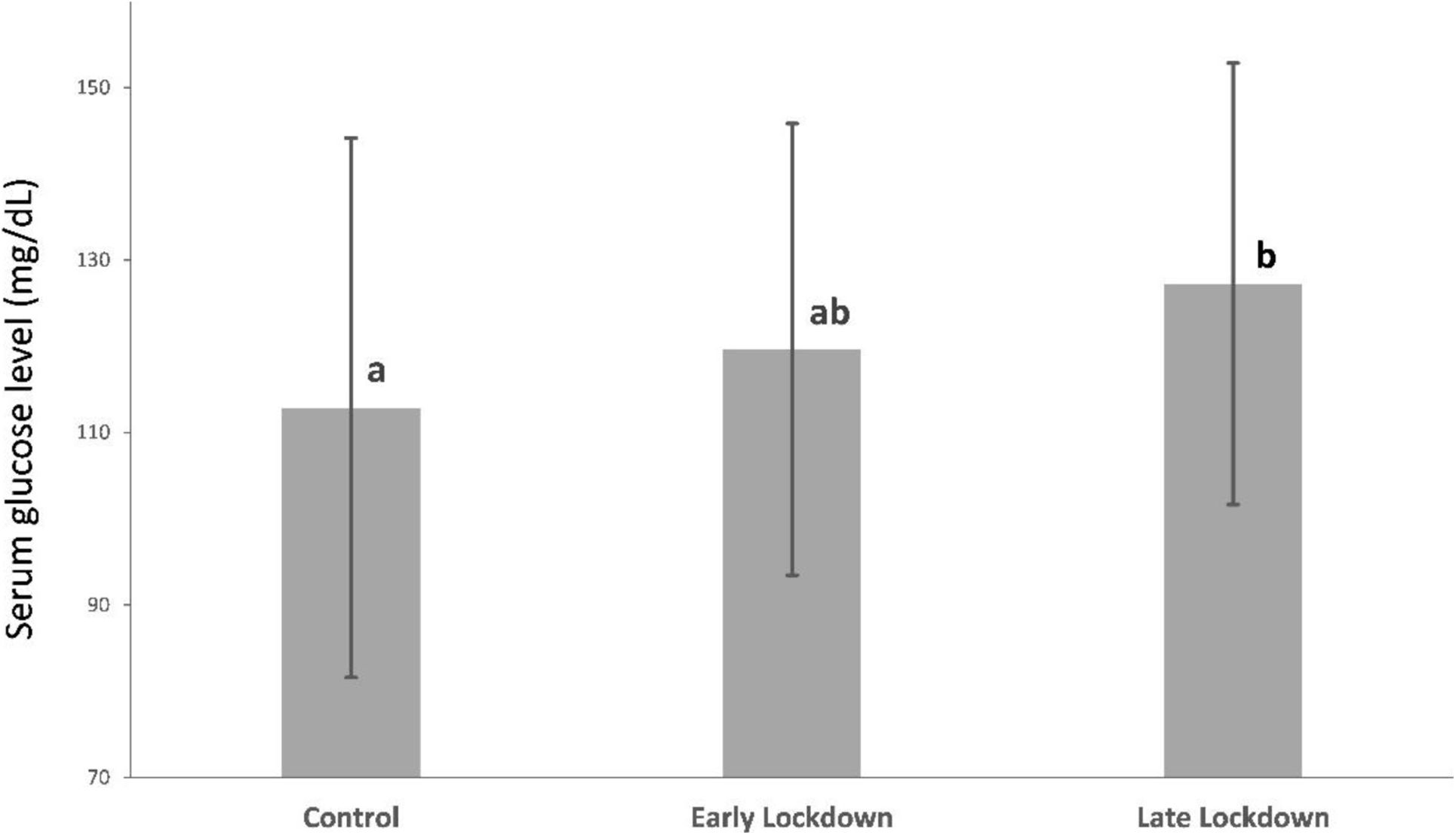

When comparing the early lockdown group and the control group, there was a 6% increase in serum glucose levels, with no significant differences between the groups (119.64±26.18mg/dL vs. 112.86±31.28mg/dL; p>0.05). However, when comparing the late lockdown group and the control group, there was a 12.7% increase (14.36mg/dL) and statistical differences were observed (127.22±25.59mg/dL vs. 112.86±31.28mg/dL; p=0.009). Moreover, no differences were found between the early and late lockdown (119.64±26.18mg/dL vs. 127.22±25.59mg/dL; p>0.05) (Fig. 3).

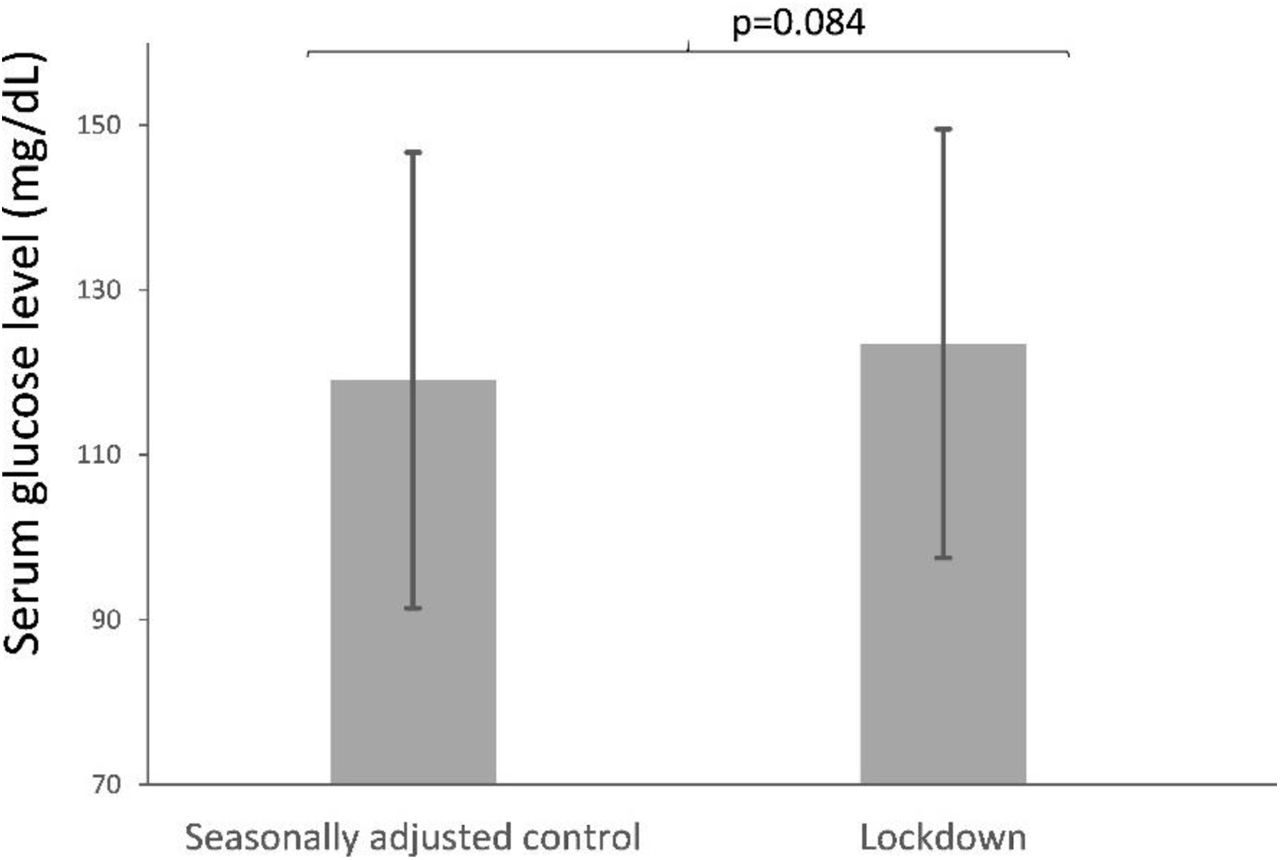

Serum glucose after O'Sullivan test between lockdown group and seasonally adjusted control group were compared an increase of 3.75% (4.47mg/dL) of serum glucose levels and a statistical trend were found (123.51±26.02mg/dL and 119.04±27.66mg/dL; p=0.084) (Fig. 4).

Additionally, when early lockdown group and seasonally adjusted control group were compared no differences were found (119.64±26.18mg/dL vs. 119.04±27.66mg/dL; p>0.05) whereas an increase of 6.87% (8.18mg/dL) and a statistical trend were observed in late lockdown group and seasonally adjusted control group (127.22±25.59mg/dL vs. 119.04±27.66mg/dL; p=0.089). Furthermore, early and late lockdown groups were also compared with early and late seasonally adjusted controls and no differences were observed (119.64±26.18mg/dL vs. 119.82±26.18mg/dL and 127.22±25.59mg/dL vs. 118.47±26.48mg/dL; p>0.05).

Furthermore, the results of the regression analysis, which incorporated all of the collected variables (Result of O'Suvillan test, Maternal Age, BMI, and Nulliparity) indicated that the lockdown group was associated with an increased glycemia in O'Suvillan test (OR=1.01; 95% CI: 1.003528–1.024592; p=0.009).

The comparison of the proportion of women with GDM in the different groups revealed no statistically significant differences (13.3% in the lockdown group, 8.9% in the control group, and 6.06% in the seasonally adjusted control, respectively; p>0.05). When proportions of positive O'Sullivan test women who were diagnosed with GDM were compared differences were found between the lockdown group and the seasonally adjusted control group (60% in the lockdown group vs. 26.06% in the seasonally adjusted control group; p<0.05). No significant differences were observed between the lockdown and control group, nor between the control groups. (60% lockdown group vs. 38.89% in the control group; p>0.05 and 38.89% control group vs. 26.06% seasonally adjusted control group; p>0.05) (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the diagnosis of GDM showed a statistical trend to be three times more prevalent in the lockdown group (OR=3; 95% CI: 0.9492337–9.481331; p=0.06).

The proportion of pregnant women who test positive for the O'Sullivan test and subsequently were diagnosed with GDM (%) from the lockdown group (n=90), control group (n=79) and seasonally adjusted control group (n=66). Different letters (a, b) indicate a significant difference between experimental groups (p<0.05).

Regarding BMI at 24 weeks no differences were found when the different groups were compared (p>0.05).

When a correlation between the lockdown duration in months and the results of O'sullivan test (mg/dL) a positive but no statistical correlation was established (r=0.0729; p=0.4947).

DiscussionIn the annals of collective memory, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered one of the most severe social milieus in Spain, as well as in numerous other regions of the world. The Spanish government's approach to impeding the transmission of Covid-19 was rigorous, involving strict limitations on outdoor physical activities for several months.9,16 The strategy aimed to reduce the spread of the virus. During this period, one legitimate reason to be outside on foot are dog owners who are allowed to take their pets for a brief stroll for welfare reasons. However, pregnant women were unable to participate in physical exercise outdoors and more importantly they were deprived of the community's health assets. The role of the primary care team as a facilitator of self-management in the prevention of GMD was also limited.

Our investigation found that the COVID-19 lockdown had an impact on O'Sullivan test results, causing a rise in serum glucose levels in non-diabetes pregnant women and an increased proportion of diagnosis of GDM in women who were previously positive in O'Suvillan test in the lockdown group. Similar to our study, but investigating women at high risk of GDM (previous GDM, first-trimester fasting glucose 100–125mg/dL, BMI≥30kg/m2) in Italy during the COVID-19 lockdown, found an increase in GDM diagnosis also. However, contrary to our work the mean serum glucose levels in the 2-h oral glucose tolerance test showed no difference.17

Glycemic levels have been rapidly increasing in both developed and developing countries having resulted in a rise in prediabetes and diabetes prevalence. According to pooled data from 2.7 million adults who participated in health surveys and epidemiological studies, the age-standardized mean fasting plasma glucose was 97.2mg/dL in women in 2008. This represents a 1.85% (1.8mg/dL) increase since 1980 (28 years).18 In our study, a few months of lockdown were able to increase 9.43% in serum glucose levels (10.65mg/dL) in the case of the lockdown group or 12.7% (14.36mg/dL) in late lockdown group compared to the control group, reinforcing the lockdown's stressful effect on pregnant women's metabolism. However, no differences were found in O'Sullivan pathological test (glucose above 140mg/dL) between lockdown and control group, although in some populations previous studies has demonstrated that impaired glucose test has not risen despite increasing diabetes incidence.19

It is important to note that hyperglycemia has previously been shown to have consequences on the organism. At the cellular level, an increase in glucose-mediated glycation occurs, which is one of the main causes of chemical modification and spontaneous injury of cellular and extracellular proteins in physiological systems.20 Non-enzymatic glycation can form advanced glycation end products (AEG) that alter the normal structure and function of proteins.21,22 These AEG trigger complex mechanisms that are related to aging, neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, inflammatory states, microvascular and macrovascular complications, and cancer.23–31 It has been also demonstrated that the generation of AEG during gestation is higher in women diagnosed with gestational diabetes compared to those who are not diagnosed, at 24–29 and 33–41 weeks.32 Moreover, high first-trimester serum AGE level was found to be associated with adverse perinatal outcomes even in non GDM women.33

Lessons learned from the connections between natural disasters and negative effects on human health, including complications during pregnancy have been published. For instance, a research project conducted in New York State found an increased vulnerability to GDM following prolonged power outages caused by Hurricane Sandy.34 This study stated a significant increase of 42.3% (95%CI 15.0–76.0%) in emergency department visits concerning diabetes or blood sugar level abnormalities in New York State.34

In our study, we also examined the effect of different lengths of confinement before the O'Sullivan test in pregnant women. When comparing the glucose levels of pregnant women in the early stages of lockdown (early lockdown group) with those who experienced longer periods of confinement while pregnant (late lockdown group), we found a significant increase in the latter compared to the control group. This difference was not found between the early and control groups, indicating that time in confinement is important. Same results (but at 34 weeks of gestation) were obtained in a Chinese's COVID-19 lockdown study in which normoglycemic women in late pregnancy been associated these with higher fasting glucose level compared to control (before COVID-19).35 The control group in this investigation used the same months of the lockdown but previous year. We also investigated these months in our seasonally adjusted control group. In our case only statistical trends were obtained when the levels of glucose obtained from the O'Suvillan test in lockdown group was compared to the adjusted control and when the late lockdown was compared with adjusted control group, reinforcing the fact that the length of the confinement matters. Similar to the Chinese study, we also were able to demonstrate an increased proportion of diagnosis of GDM in women who were positive in O'Suvillan test in the lockdown group compared to this adjusted control group. However, our study did not reveal any statistically significant differences between the groups in the overall proportion of women diagnosed with GDM even though the prevalence of GDM was found to be twice as high in the lockdown group compared to the seasonally adjusted control (13.3% in the lockdown group, 6.06% in the seasonally adjusted control, respectively; p>0.05). Other authors reported the rate of GDM in Spain to be 5.3%, similar to our seasonally adjusted control group and less than half the rate in the lockdown group.3

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed many aspects of our lives. It is unlikely that the rise of the serum glucose level of pregnant women can be attributed to any one cause.36 First and foremost, during the COVID-19 lockdown, most health care resources were devoted to fighting the pandemic, making it difficult for expectant mothers to receive timely and thorough prenatal care to manage their own health. Apprehensions related to encountering COVID-19 cases in healthcare facilities, following governmental advisories to stay at home, and restrictions on transportation and the access to health assets may also lead pregnant women to reduce their prenatal care. Regarding women care, some studies have examined the effects of Covid-19 lockdowns on dietary habits and physical activity in non-pregnant and pregnant women with type 2 diabetes mellitus.37,38 These investigations reported that women exercised less compared to before COVID-19 restrictions when they walked with friends, walked to work, had jobs involving physical activity, or took exercise classes. Moreover, an increase in bread consumption, a decrease in battered fish and fries and snacking more were reported attributing this to boredom by the women.12 Furthermore, the stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic like isolation, social distancing measures, and deteriorating economic conditions during the pandemic were factors affecting mental health and metabolism during pregnancy.39–42 Moreover, psychological distress like the one suffered with the lockdown was reported to be positively associated with glucose levels in pregnant women and consistently recognized as a pervasive risk factor for GDM.43

In our study the BMI at 24 weeks and increment of BMI was investigated but no differences were found. Contrary other authors have published evidence shown an uptick in weight gain among individuals during lockdowns.44 Lockdowns referred an elevated intake of snacks and carbohydrates, alongside a significant decrease in mobility and altered physical activity modes, all of which cumulatively lead to increased maternal BMI.3,37

In conclusion, this study presents the first quantitative evaluation of the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on a Spanish cohort of urban pregnant women within a medium-high purchasing power receiving primary healthcare. The study explores the relationship between the lockdown and the serum glucose levels of the O'Sullivan test and the diagnosis of GDM. We found that the COVID-19 lockdown was associated with an increase in serum glucose after O'Sullivan test in pregnant women in Poniente Primary Health Care center. Furthermore, the proportion of diagnosed gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) among pregnant women with positive test results in O'Sullivan was higher in the lockdown group. The findings of our study emphasize the essential requirement for comprehensive maternal services, the modification of hygienic and dietary recommendations on the part of the health professionals and the access to community's health assets during future lockdown scenarios. Further research would be necessary to clarify the association between lockdown measures and GDM in other Spanish contexts. This broader comprehension is vital for informing precise interventions and protecting maternal health.

Strengths and limitationsThere present study has several strengths. This is the first quantitative evaluation of the effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on a Spanish cohort of non-DM pregnant women receiving primary healthcare. We exploring for the first time its correlation with the risk of GDM using O'Sullivan test following the GEDE (Spanish Diabetes and Pregnancy Group) that continues to recommend a two-step diagnosis. Our study avoided selection bias by selecting all the community pregnant mothers except those who have previously been diagnosed with DM. We examined not only the link between exposure to the COVID-19 lockdown and the risk of GDM but also revealed the exposure-response relationship, demonstrating the cumulative effect of the lockdown duration on the risk and diagnoses of GDM.

Additionally, we utilized stringent contemporaneous and seasonal control measures to mitigate the effects of seasonal variations on GDM rates. To evaluate seasonal variations, we calculated the difference of O'Sullivan test results between the exposed cohort and the general population of pregnant women during the same period in the previous year. After adjusting for factors like maternal age, BMI and Nulliparity we found no significant correlation between the lockdown and GDM risk. However, we observed a notable elevation in serum glucose levels and a greater proportion of women with positive O'Sullivan test results who were diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in the lockdown group. These methodological strengths support the causal reasoning behind our results.

Several limitations should be also considered. Firstly, the retrospective design of our study was a consequence of the unforeseen emergence of COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdown measures. This design limits our ability to definitively establish a causal relationship between lockdown measures and the incidence of GDM. Secondly, all participant information was obtained exclusively from their medical records and general statistics. The study population comprises women residing in Cordoba in an urban environment and with a medium-high purchasing power. Certain individual covariates, such as, familial predisposition to type 2 DM, smoking, and alcohol consumption, were unavailable for analysis in this study, thus leaving undetermined their potential impact on the observed association. Additionally, even though we used all the O'Sullivan test within Poniente Primary Health Care center in Córdoba (Spain) the limited size of the recruited cohort of pregnant women may diminish the study's statistical power.

- -

The COVID-19 lockdown was associated with an increase of serum glucose level after O'Sullivan test in pregnant women.

- -

The length of the lockdown was associated with a higher increase in glucose after O'Sullivan test in pregnant women.

- -

The lockdown resulted in an increase in the proportion of diagnoses of gestational diabetes mellitus among women with positive O'Sullivan test results.

- -

It is of paramount importance to guarantee the access to community's health assets that lead to a correct prenatal care to pregnant women in future sanitary emergencies.

The study was approved by an institutional review board PEIBA (Biomedical Research Ethics Portal of Andalusia) (5385 TFG-ODGCOVID-2022). The study has followed the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was not required for retrospective studies.

FundingThis research did not receive any financial support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit organizations.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We would like to acknowledge Primary health care team of Poniente primary center care center for its support in this investigation and to the Servicio Andaluz de Salud.

We also want to thanks Guadalupe Ruiz Merino part of Murcia's Institute of Biosanitary Research for her biostatistics support.