Introduction

Communication is the cornerstone of the physician-patient relationship, and has been the subject of many studies in recent decades.1,2 Most of these studies have centered on the (positive) influence of communication on compliance with treatment and user satisfaction,3-5 within a paternalistic relationship where the physician (the expert) makes the decisions that concern the patient.

More recently, social changes have brought the importance of communication to the fore once again, this time as a prerequisite for patient autonomy6,7 (one of the basic pilars of bioethics) and the patient's right to information.8,9 This reflects a more deliberative and participatory model of relationship between health care professionals who no longer play the leading role, and patients who may be more like well-informed experts themselves,10,11 and whose satisfaction with the relationship may be greater.12

Although this trend and the debate certain topics have generated (informed consent,13 patients' rights) are clearest in the setting of specialized care--because of the greater transcendence of the decisions that need to be made--we should not neglect that most visits with physicians take place in primary care, where physician-patient communication is the best technology available for the process of diagnosis and treatment.14

Against this background we felt it would be of interest to evaluate the information supplied by family physicians during consultations, the information requested by patients, and the patient´s participation in decision-making.

Material and Methods

The descriptive, cross-sectional study involved 3 health centers in the Toledo health care area, one rural (Polán) and 2 urban (Santa María de Benquerencia and Sillería). Both urban centers were located in the city of Toledo.

The study population consisted of visits to the doctor by patients who sought care for an acute illness. We included the first patients to arrive on each day between 15 January and 15 March 2003 at walk-in offices staffed by 6 family physicians accredited as tutors for residents in training. To estimate the percentage participation of patients during the visit, 143 visits were considered sufficient assuming an expected frequency of 30%, a P value <.05 and a precision of ±8%.

The study was based on observation of the visit by a resident in family medicine without the tutor´s knowledge. Patients whose examination was performed in whole or in part by a resident were excluded from the study population, and the next patient to fulfill the inclusion criteria was included.

The resident then completed a questionnaire with items on the following variables: age, sex, information provided by the physician and requested by the patient (cause, diagnosis, complementary tests, treatment, dosage, complications of treatment, prognosis), and an assessment of whether the patient had or had not participated in decision-making regarding complementary tests or treatment.

Later, the patients were interviewed by telephone to determine their degree of satisfaction with the information received and comprehension of the information. For patients younger than 14 years of age the telephone interview was conducted with the person who accompanied the child during the visit to the physician's office.

Before the study was begun the observers were trained with simulated interviews.

Statistical analyses of the data were done with the SPSS v. 10.0 program, using descriptive and analytical tools. Percentage values were compared with Pearson's *2.

Results

A total of 152 clinical interviews were observed, all of which were considered valid. Mean age of the patients was 41.08 years (SD 18.56 years), and 55.90% were women.

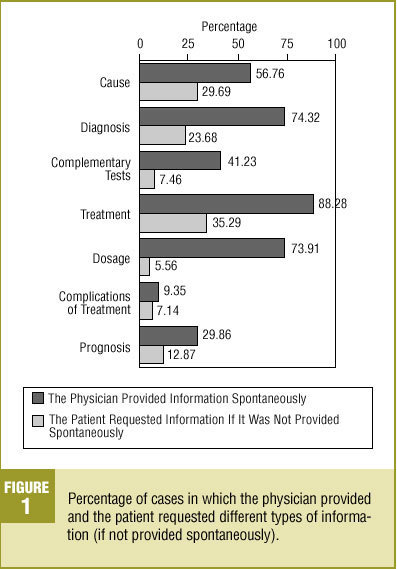

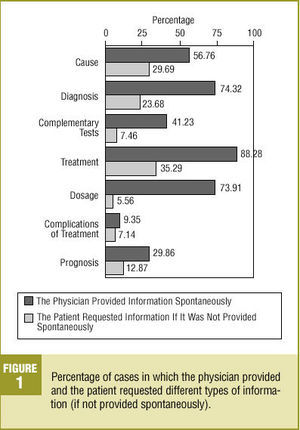

None of the visits was characterized by a complete lack of information provided spontaneously by the physician. The type of information supplied most frequently to patients (Figure 1) was that regarding treatment, recorded in 88.28% of the interviews (95% CI, 81.63%-92.82%), and the type least frequently provided was that regarding possible complications of treatment, recorded in 9.35% (95% CI, 5.28%-15.77%).

Figure 1. Percentage of cases in which the physician provided and the patient requested different types of information (if not provided spontaneously).

Of the 152 interviews, the patient requested no further information in 55 (36%-18% [95% CI, 28.67%-44.41%]) regardless of whether the physician had previously provided information spontaneously or not. The topics patients requested information about most often were, in decreasing order, cause (29.6%), treatment (28.9%), diagnosis (21.7%), complementary tests (16.4%), prognosis (13.2%), dosage (11.2%) and complications of treatment (8.6%). The types of request for specific information made when the physician did not provide this information spontaneously are shown in Figure 1. The most frequent requests were for information about treatment (35.29% [95% CI, 15.26%-61.38%]) and cause of the symptoms (29.69% [95% CI, 19.25%-42.58%]).

In the telephone interview (Table 1), 94.0% (95% CI, 88.58%-97.04%) of the participants considered the information they received to be sufficient; however, 22.7% (95% CI, 16.41%-30.36%) said that when they left the doctor's office there was something they wished they had asked about. We found no significant differences between sexes or age groups for these two variables. Of the 34 patients who had something they wished they had asked the doctor, 10 (29.4%) requested no further information.

The results for comprehension of the information were similar: 18.67% (95% CI, 12.96%-26.02%) of the patients we interviewed said they had not fully understood the information provided during the visit. There were no statistically significant differences between men and women (22.73% vs 15.48%; *2=1.73 [P>.05]), nor did we find any relationship between this variable and age. Of the 28 patients who said they had not fully understood the information, 11 (39.28%) did not ask the physician for any further information.

The observers considered that 69.39% (95% CI, 61.17%-75.57%) of the patients did not participate in decision-making about their treatment. This figure increased to 75.41% (95% CI, 66.63%-82.55%) with regard to decision-making for complementary tests.

Discussion

Before we begin the discussion of our results, we should clarify a few points about the study. We opted to include only visits for acute illness because patients with a chronic illness receive information gradually, and this makes it more difficult to evaluate the information provided or requested. In contrast, acute processes are often a new experience for the patient, and their need for information on the spot is clearer. This makes it easier to observe which types of information are provided and requested.3

Possible sources of bias should also be noted. One such bias is that arising from the small number of physicians we were able to observe, given the nature of the study. In addition, the participating physicians were tutors responsible for training the residents who acted as observers, and thus may have been more likely to give particular consideration to the importance of the clinical interview and the information provided to patients. Moreover, despite the considerable training the residents received, a non-negligible degree of observer subjectivity is involved in interpreting a generally complex event such as the clinical interview. For these reasons we believe our results, while valid, should be considered with due caution.

Because of the methods used in this study, it was difficult to compare our findings with those of other studies, most of which were based on opinions provided by patients and which did not attempt to describe the information interchange. In general, we believe the information health care professionals provide to patients is not as complete as it might be, especially with regard to specific aspects of the symptoms such as their possible causes, the prognosis, and the possible complications of treatment. The types of information provided most frequently dealt with the diagnosis and treatment (although the actual information provided also showed room for improvement), possibly because these aspects are considered more basic. This assumption is supported by the fact that, as others have noted previously3,15 and as seen in the present study, the patient´s interest usually centers on these two aspects of his or her illness.

The main reason that is likely to explain why information provided to patients is inadequate is the shortage of time available to primary care physicians to see all their patients.16-18 Another possible cause is the fact that many visits were motivated by a mild illness for which the physician may have felt extensive explanation was unnecessary. In any case, a consequence of these factors may be that patients acquire insufficient knowledge of their illness, and are thus more likely not to comply with or adhere to treatment. This in turn may lead to further requests for care.19

In general, we found that patients usually ask few questions even when the physician has not provided information beforehand. The explanation for this may lie in the fact that the patient is already familiar with the illness, or considers it not to be serious. However, the fact that almost one third of the patients who admitted there was something they wanted to ask the physician failed to raise any questions suggests other motives. These might involve, among other things, a degree of passivity on the patient´s part (patients who want only that information which is indispensable),20,21 blind trust in the physician,22 or impediments to communication (specialized medical language, highly directed interchange).3,23

If we accept that one of the main aims of the clinical interview is to inform the patient, and although the great majority of patients responded that they found the information provided to be sufficient, this aim was not fulfilled in one out of every five consultations. Some patients had questions they wished they had asked, or did not fully understand the information.

Despite the trends experts have predicted,15,20,24-26 we believe that participation by patients in decision-making remains poor at the present time. Very few patients are asked their opinion on the diagnostic process or the treatment they are to follow,23,27 even though it has been shown that participation in decision-making has a favorable effect on the efficacy of treatment.21 This situation shows how far we are from the model of shared deliberation in which information flows in both directions, favoring joint decision-making between the physician and the patient.6,12,15 It would be interesting to investigate in greater depth the reasons that make it difficult for patients to participate more fully in consultations with their primary care physician.

In closing, we wish to restate our conviction that family physicians should play the role of information provider that society has already begun to demand of us.9,21,28 In the words of Meneu,20 "sharing information is not the same as making decisions, but the former is a prerequisite for the latter."