This study was aimed at evaluating the appropriateness of use and interpretation of rapid antigen detection testing (RADT) and antibiotic prescribing for acute pharyngitis six years after a multifaceted intervention.

DesignBefore-and-after audit-based study.

LocationPrimary care centres in eight autonomous Communities.

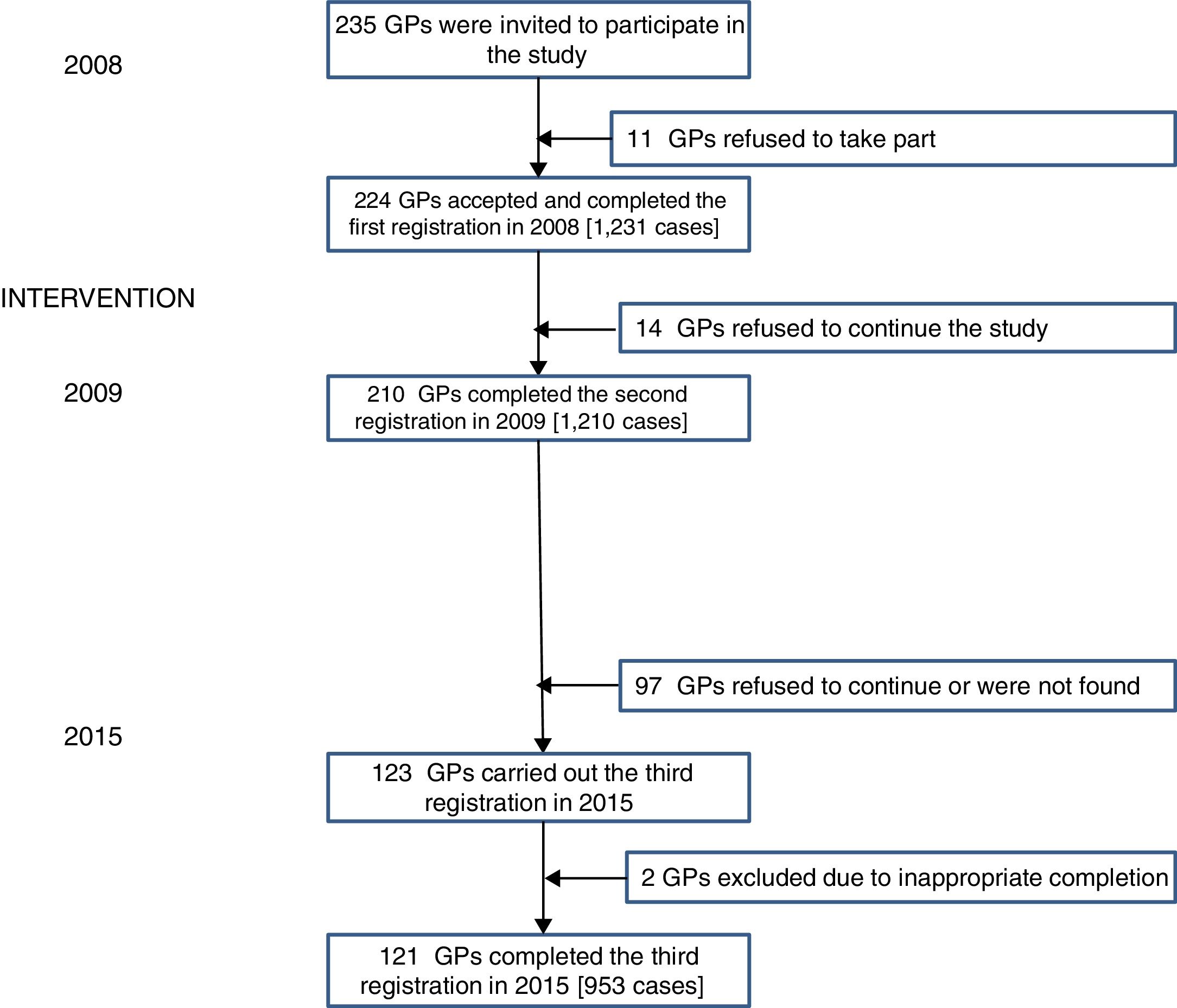

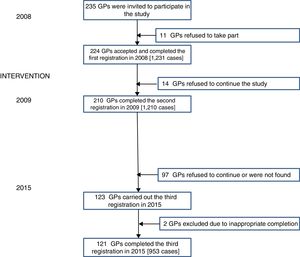

ParticipantsGeneral practitioners (GP) who had participated in the HAPPY AUDIT intervention study in 2008 and 2009 were invited to participate in a third audit-based study six years later (2015).

MethodRADTs were provided to the participating practices and the GPs were requested to consecutively register all adults with acute pharyngitis. A registration form specifically designed for this study was used.

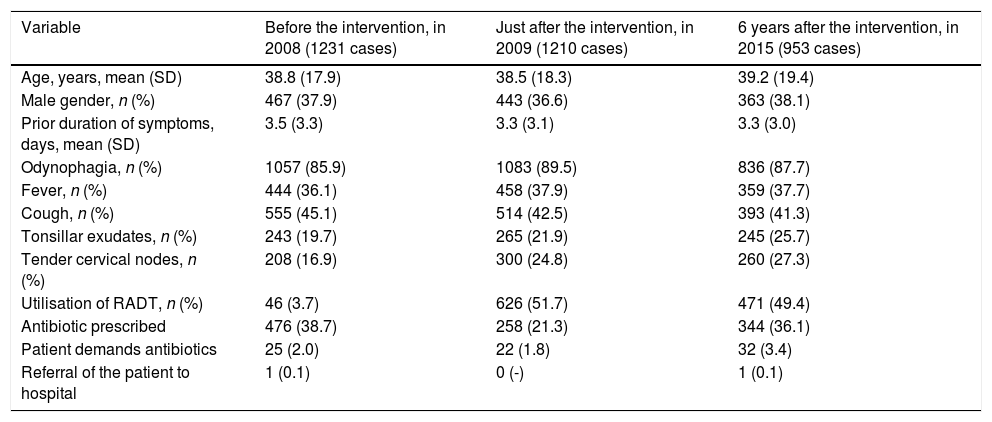

ResultsA total of 121 GPs out of the 210 who participated in the first two audits agreed to participate in the third audit (57.6%). They registered 3394 episodes of pharyngitis in the three registrations. RADTs were used in 51.7% of all the cases immediately after the intervention, and in 49.4% six years later. Antibiotics were prescribed in 21.3% and 36.1%, respectively (P<.001), mainly when tonsillar exudates were present, and in 5.3% and 19.2% of those with negative RADT results (P<.001). On adjustment for covariables, compared to the antibiotic prescription observed just after the intervention, significantly more antibiotics were prescribed six years later (odds ratio: 2.24, 95% confidence interval: 1.73–2.89).

ConclusionsThis study shows that that the long-term impact of a multifaceted intervention, focusing on the use and interpretation of RADT in patients with acute pharyngitis, is reducing.

Evaluar la adecuación del uso e interpretación de las técnicas antigénicas rápidas (TAR) y la prescripción antibiótica en la faringitis aguda 6 años después de haber realizado una intervención multifacética.

DiseñoEstudio antes-después basado en una auditoria.

EmplazamientoCentros de salud en 8 comunidades autónomas.

ParticipantesSe invitaron a médicos de familia (MF) que ya habían participado en el estudio de intervención HAPPY AUDIT en 2008 y 2009 a un nuevo AUDIT 6 años después (2015).

MétodoSe proporcionaron TAR a los centros participantes, y se pidió a los MF que registraran consecutivamente a todos los adultos con faringitis aguda. Usamos un registro diseñado específicamente para este estudio.

ResultadosCiento veintiuno MF de los 210 que participaron en los primeros registros (57,6%) aceptaron a participar en el tercer registro. Se registraron 3.394 episodios de faringitis agudas en las 3 auditorías. Se usaron TAR en el 51,7% de los casos inmediatamente después de la intervención y en el 49,4%, 6 años después. Se prescribieron antibióticos en el 21,3%y 36,1%, respectivamente (p<0,001), principalmente cuando había exudado amigdalar y en el 5,3 y 19,2% de los resultados de TAR negativos (p<0,001). Después de ajustar por las distintas covariables, comparado con la prescripción antibiótica observada justo después de la intervención, prescribieron significativamente más antibióticos 6 años más tarde (odds ratio: 2,24 [IC 95%: 1,73-2,89]).

ConclusionesEste estudio muestra que se reduce el impacto de una intervención multifacética a largo plazo enfocada al uso e interpretación de TAR en pacientes con faringitis aguda.

Sore throat in adults is one of the most common respiratory infections in Western countries, resulting in a significant amount of absenteeism from work.1 It is also one of the most common reasons for prescribing antibiotics in Spain, with a current prescription rate of 48%.2 However, group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus (GABHS), which is the most important bacterial cause of acute pharyngitis, is responsible for only 5–15% of all cases in adults.1,3 Studies have shown a significant correlation between antibiotic prescribing in primary care and the individual risk for selection of antimicrobial resistant strains.4,5 Since most antibiotics are prescribed in primary care and studies have shown that the effect is questionable for many upper respiratory tract infections such as sore throat,6 reducing inappropriate prescribing in primary care is paramount.7 Several strategies have been developed to reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescribing in the community with little success, but in general, interventions based on multiple initiatives have been found to be more effective than those focused on only one initiative. Most studies have evaluated the short-time effect of interventions, while only a few studies have assessed the long-term effect.8,9

The Health Alliance for Prudent Prescribing, Yield and Use of Antimicrobial Drugs in the Treatment of respiratory tract infections project (HAPPY AUDIT) was a study financed by the European Commission. This study was aimed at strengthening the surveillance of respiratory tract infections in primary healthcare through the development of intervention programmes targeting general practitioners (GP) and changing people's habits towards prudent use of antimicrobial agents, with the provision of point-of-care tests, such as rapid antigen detection tests (RADT).10 This intervention was effective for reducing the number of antibiotics prescribed in six different countries (Sweden, Denmark, Lithuania, Russia, Spain and Argentina).11 Spain included the greatest number of GPs and in order to assess the long-term effect of the intervention we decided to perform a new audit-based registration six years after the first intervention.

In a previous study we showed that in relation to the number of unnecessary antibiotics prescribed, the overall effect of the HAPPY AUDIT intervention was sustainable after six years, despite a slight non-significant increase being observed.2 In this study, we focussed on the long-term effect of the use and interpretation of RADT testing in patients with acute pharyngitis. Since the use of rapid tests in Spain is scarce, we investigated how GPs used and interpreted these tests in patients with pharyngitis. We assessed the participating physicians immediately after the intervention and six years later. As secondary objectives, we evaluated the percentage of antibiotics prescribed and the predictors of antibiotic prescribing depending on the presence of the different clinical criteria in both periods.

MethodsDesign and study populationGPs who had participated in a before-and-after audit-based study in 2008 and 2009 in eight different autonomous regions in Spain (Madrid, La Rioja, Asturias, Galicia, Andalusia, Valencia, Canary Islands and Balearic Islands) were invited by local coordinators to participate in a new registration study in 2015. Patient registration took place during 3-weeks (15 working days) in the winter months – January to February – in 2008 (first registration), 2009 (second registration), and 2015 (third registration). All GPs were requested to consecutively register patients (≥16 years) with respiratory tract infections. In this study, we only considered the patients, in whom the main diagnosis was acute pharyngitis, including acute tonsillitis. Patients were registered by means of a specific template according to the Audit Project Odense method previously described by Munck et al.12

InterventionShortly after the first registration the GPs were invited to follow-up meetings where they received individual prescriber feedback from the first registration. One to three months before the second registration (November and December 2008) the participating GPs received the following intervention programme: (1) a training course on the appropriate use of antibiotics for respiratory tract infections; (2) clinical guidelines with recommendations for diagnosis and treatment; (3) access to RADT; and (4) training in the use and interpretation of RADTs. GPs were then advised to use RADT in cases of doubt and not as a stand-alone test, specifically only in patients with suspected streptococcal pharyngitis (two or more Centor criteria) as recommended by local guidelines.13 GPs were instructed only to prescribe antibiotics in patients with positive RADT results.

The availability of RADTs in Spanish primary care is scarce, but we ensured that all the participating GPs still had access to RADT after six years. However, the coordinators in each area did not investigate if the results of the rapid tests were interpreted appropriately. Neither did they give any other information about guidelines and appropriate utilisation of antibiotics in order to avoid any further intervention.

Statistical analysesThe data were analysed with the Stata v.13 statistical programme. Characteristics of the study population were described using frequencies for categorical variables, and mean (SD) for quantitative variables. To compare the baseline characteristics of the GPs we used a χ2 tests for categorical variables and t Student–Fisher tests for continuous variables. Data analysed in a hierarchical multilevel logistic regression model was first estimated with two levels: patients with pharyngitis and GPs. Predictors of antibiotic prescribing were also analysed in two logistic regression models, one for the doctors assigned to the intervention immediately after this and another for the same group of doctors six years after the intervention, considering antibiotic prescribing as the dependent variable (yes/no). Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were estimated. The appropriate use of RADT and appropriate antibiotic prescribing were determining by calculating the Centor scores and the use of χ2 tests. Statistical significance was considered with p<0.05.

Ethical approval was granted by the Institut d’Investigació en Atenció Primària Jordi Gol i Gurina, Barcelona, reference number 14/106. Anonymity guaranteed and confidentiality, as well as the protection of data.

ResultsA total of 123 GPs of the 210 GPs who had participated in the first and second registrations agreed to participate in the third registration in 2015; however, two GP were excluded due to insufficient completion of the templates for registration. Valid data were therefore only obtained from 121 GPs (57.6% of all the GPs who underwent the intervention in 2008) (Fig. 1).

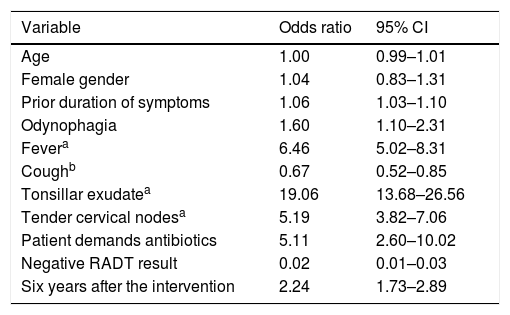

Antibiotic prescribingGPs included a total of 3394 cases of acute pharyngitis in the three audits (2008, 2009 and 2015). GPs prescribed significantly more antibiotics six years after the intervention compared to the short-term intervention (36.1% vs. 21.3%; p<0.001) (Table 1). Data were analysed in a two-level logistic regression model with patients with pharyngitis (n: 3298) allocated to level 1 and GPs (n: 121) to level 2. Tonsillar exudate (OR: 19.06: 95% CI: 13.7–26.6) was significantly associated with antibiotic prescribing and conversely, a negative RADT result (OR 0.02: 95% CI: 0.01–0.03) was associated with low antibiotic prescribing (Table 2). On adjustment for covariables, compared to the antibiotic prescription observed just after the intervention, GPs prescribed significantly more antibiotics six years later (OR: 2.24, 95% CI: 1.73–2.89). As described in Table 2, tonsillar exudate was the strongest predictor for antibiotic prescribing among the different Centor criteria.

Baseline characteristics of the contacts with acute pharyngitis according to the year of registration (n=121 GPs).

| Variable | Before the intervention, in 2008 (1231 cases) | Just after the intervention, in 2009 (1210 cases) | 6 years after the intervention, in 2015 (953 cases) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 38.8 (17.9) | 38.5 (18.3) | 39.2 (19.4) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 467 (37.9) | 443 (36.6) | 363 (38.1) |

| Prior duration of symptoms, days, mean (SD) | 3.5 (3.3) | 3.3 (3.1) | 3.3 (3.0) |

| Odynophagia, n (%) | 1057 (85.9) | 1083 (89.5) | 836 (87.7) |

| Fever, n (%) | 444 (36.1) | 458 (37.9) | 359 (37.7) |

| Cough, n (%) | 555 (45.1) | 514 (42.5) | 393 (41.3) |

| Tonsillar exudates, n (%) | 243 (19.7) | 265 (21.9) | 245 (25.7) |

| Tender cervical nodes, n (%) | 208 (16.9) | 300 (24.8) | 260 (27.3) |

| Utilisation of RADT, n (%) | 46 (3.7) | 626 (51.7) | 471 (49.4) |

| Antibiotic prescribed | 476 (38.7) | 258 (21.3) | 344 (36.1) |

| Patient demands antibiotics | 25 (2.0) | 22 (1.8) | 32 (3.4) |

| Referral of the patient to hospital | 1 (0.1) | 0 (-) | 1 (0.1) |

GP: general practitioner; RADT: rapid antigen detection tests; NC: not collected; SE: standard error.

Effect of an intervention 6 years later. Multivariable predictors of antibiotic prescription in acute pharyngitis (n=3.298 patients: 121 GPs).

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 |

| Female gender | 1.04 | 0.83–1.31 |

| Prior duration of symptoms | 1.06 | 1.03–1.10 |

| Odynophagia | 1.60 | 1.10–2.31 |

| Fevera | 6.46 | 5.02–8.31 |

| Coughb | 0.67 | 0.52–0.85 |

| Tonsillar exudatea | 19.06 | 13.68–26.56 |

| Tender cervical nodesa | 5.19 | 3.82–7.06 |

| Patient demands antibiotics | 5.11 | 2.60–10.02 |

| Negative RADT result | 0.02 | 0.01–0.03 |

| Six years after the intervention | 2.24 | 1.73–2.89 |

CI: confidence interval; RADT: rapid antigen detection test.

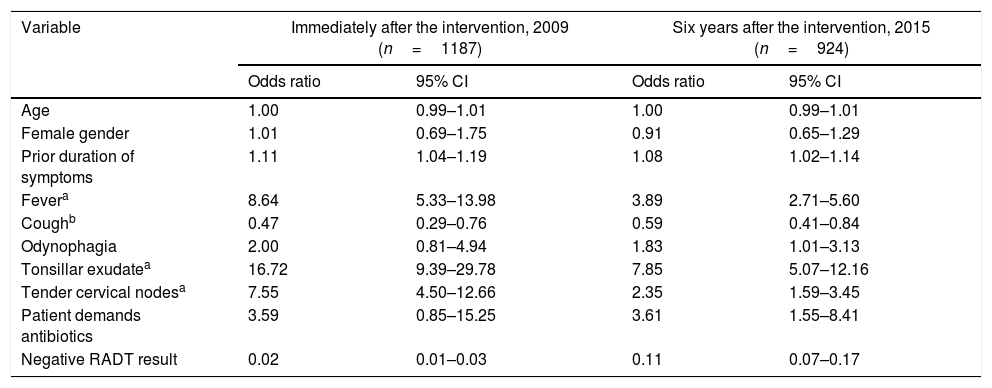

The presence of tonsillar exudate was a strong predictor for antibiotic prescribing both immediately after the intervention (OR 16.7; 95% CI, 9.4–28.8) and after six years (OR 7.8; 95% CI, 5.1–12.2) (Table 3). Cough was a negative predictor for antibiotic prescribing both immediately after the intervention and after six years. A negative result of RADT was also a negative predictor for antibiotic prescribing, both immediately after the intervention (OR: 0.02) and after six years (OR: 0.11).

Predictors of antibiotic prescribing for patients with acute pharyngitis immediately after the intervention and six years later.

| Variable | Immediately after the intervention, 2009 (n=1187) | Six years after the intervention, 2015 (n=924) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 |

| Female gender | 1.01 | 0.69–1.75 | 0.91 | 0.65–1.29 |

| Prior duration of symptoms | 1.11 | 1.04–1.19 | 1.08 | 1.02–1.14 |

| Fevera | 8.64 | 5.33–13.98 | 3.89 | 2.71–5.60 |

| Coughb | 0.47 | 0.29–0.76 | 0.59 | 0.41–0.84 |

| Odynophagia | 2.00 | 0.81–4.94 | 1.83 | 1.01–3.13 |

| Tonsillar exudatea | 16.72 | 9.39–29.78 | 7.85 | 5.07–12.16 |

| Tender cervical nodesa | 7.55 | 4.50–12.66 | 2.35 | 1.59–3.45 |

| Patient demands antibiotics | 3.59 | 0.85–15.25 | 3.61 | 1.55–8.41 |

| Negative RADT result | 0.02 | 0.01–0.03 | 0.11 | 0.07–0.17 |

CI: confidence interval; RADT: rapid antigen detection test.

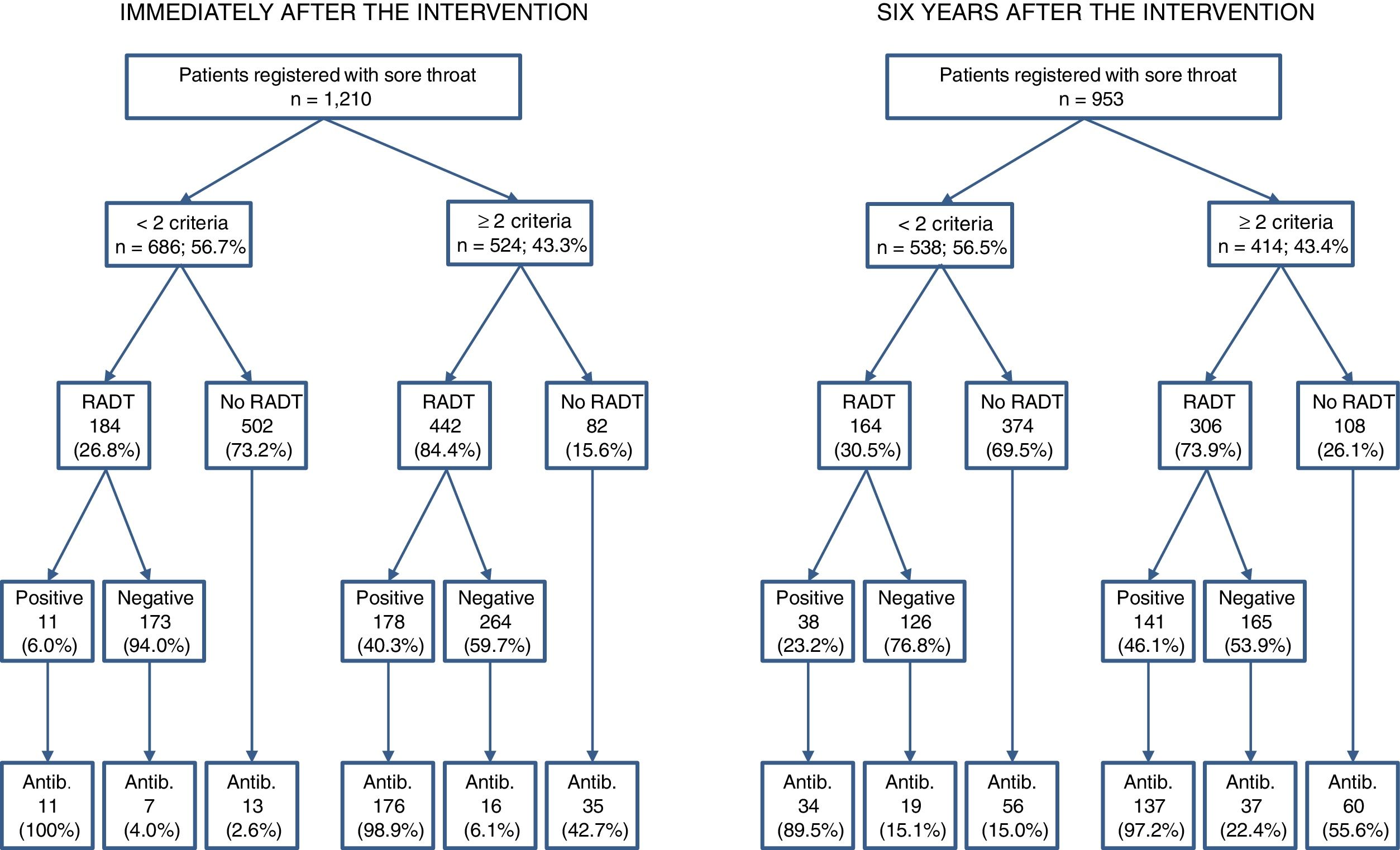

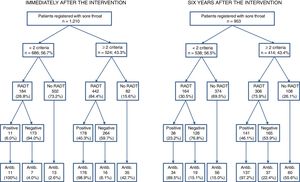

As shown in Table 1, there was a low use of RADT before the intervention (3.7%) but immediately after the intervention it increased (51.7%) and the effect was maintained after six years (49.4%). A total of 206 patients with pharyngitis presented with four Centor criteria, 472 three, 690 two and 2025, less than two criteria. RADTs were used appropriately in 78% and 71.7% of the cases immediately and 6 years after the intervention, respectively (p<0.01) (Fig. 2). RADTs were performed in 85.1%, 90.3%, 80.1% and 26.8% of these cases, respectively, immediately after the intervention, and in 81.8%, 80.4%, 67.1% and 30.5%, respectively, after six years. RADTs were used in 26.8% of the cases with less than two criteria just after the intervention and in 30.5% of all these cases 6 years after the intervention (p<0.001) (Fig. 2). Appropriate antibiotic prescribed significantly differed between both interventions (68.2% after the intervention vs. 39.9% six years later; p<0.001). Nearly all patients (97.4%) with positive RADT results were prescribed antibiotics. In patients with a negative result of RADT, however, 10.8% received antibiotics immediately after the intervention, but six years after the intervention the percentage increased to 19.2%. The rate of antibiotic prescribing was even higher in patients with a negative RADT result with two or more Centor criteria (22.4%). Conversely, the GPs prescribed antibiotics in only 23 out of the 437 negative RADT cases just after the intervention (5.3%; p<0.001) (Fig. 2).

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, no study has evaluated the long-term effect of a multifaceted intervention in primary care focussing on the management of patients with pharyngitis. Adherence to clinical practice guidelines, recommending the use of RADT in patients with two or more Centor criteria and only prescribing antibiotics to patients with positive RADT results,14 was high immediately after the intervention. However, the adherence to guidelines significantly reduced six years later.

This study has several limitations. In this study, we only considered the patients, in whom the main diagnosis was acute pharyngitis. GPs were asked to only tick off the main diagnosis of the patient. This might have led to some conditions different from sore throat being mistakenly considered as acute pharyngitis or tonsillitis and some episodes of sore throat could have been missed out and been diagnosed as another condition. However, this is inherent to daily practice, and this study was intended to be pragmatic. Another limitation to be taken into consideration is that performing an audit may in itself influence the prescribing habits. Furthermore, the prescribing habits of the participating GPs may not be representative of all GPs in Spain. However, the reliability of the audit methodology demonstrated in various projects carried out in other European countries is very high and is very well correlated with actual prescribing in medical offices.13 The greatest strength of this study was the large number of physicians included. In addition, more than 50% of the GPs who had participated in the first and second registries also accepted to participate in an audit six years later.

This is the only study that has analysed the adherence of physicians to clinical practice guidelines in the management of acute pharyngitis six years after a multifaceted intervention. In a recent study aimed at assessing the short-term impact of a multifaceted intervention, Magin et al. found a reduction in antibiotic prescribing for lower respiratory tract infections but not for sore throat, similar to the results obtained in our study.15 The lack of studies focusing on the long-term effect of interventions prevents comparison of our results with other studies.

The impact of the intervention was higher immediately after the intervention compared to six years later. The recent controversy about the need to treat bacterial causes other than GABHS, which cannot be identified with the use of current RADTs, may constitute one explanation.16 The rate of performing RADT was nearly the same after six years, but the interpretation of the results markedly differed. In 2015, a considerable number of patients with negative RADT were inappropriately prescribed antibiotics. Some professionals consider that tests are unreliable when the result is negative; however, the negative predictive value of immunochromatographic antigenic techniques, such as RADT, is very high.17,18 In the case of negative RADT results, current local guidelines recommend that patients should be treated symptomatically and asked to return if symptoms persist or worsen after five days, and if symptoms persist beyond five days, patients should be evaluated for signs and symptoms of infectious mononucleosis, peritonsillar abscess, or human immunodeficiency virus infection.14

In our study, the appropriateness of the use of RADT and how GPs interpreted their results in patients with acute pharyngitis waned six years after the intervention. In the workshops carried out in 2008, doctors became familiarised with this technique, how to perform the procedure and how to interpret the results. Since the availability of these tests is not homogeneous in Spain, RADTs were again provided to the GPs assigned to the intervention, and the local coordinators only explained how to perform the procedure, but they were very careful about not giving further guidance as to the interpretation of the results, since this had already been provided six years earlier, and we aimed to ascertain if this one-off intervention was sustainable six years later. This lack of re-intervention might explain why so many cases of negative results were associated with unnecessary antibiotic prescribing and the relatively high proportion of patients with less than two Centor criteria that had a RADT. RADTs were used in about a quarter of the patients with less than two Centor criteria immediately after the intervention, but six years after the intervention nearly one third of patients with less than two criteria underwent a RADT. Conversely, the utilisation of rapid tests for patients with two or more Centor criteria was higher immediately after the intervention compared to six years later (84.4% vs. 73.9%, respectively).

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing has also been observed in other countries such as in Scandinavia, where rapid tests have been widely used,19 but constant interventions targeting GPs have resulted in a significant decrease of unnecessary prescribing. Gröndal et al. found that some GPs consider that clinical presentations overrule the decision when the point of care test result is negative, and this is mainly due to outdated misconceptions.20 Nowadays, less than 5% of patients with negative RADT results are prescribed antibiotics in Sweden, and according to experts, this is the result of a continuous training programme aimed at improving antibiotic prescribing in primary care.21

One of the striking results of the present study is the different weight GPs allocated to the different clinical criteria. The Centor rule gives one point for each of the following: fever; absence of cough; presence of tonsillar exudates; and swollen, tender anterior adenopathy.3,13 However, Spanish GPs consider that some of these criteria are more predictive for streptococcal infection than others. The ideal percentage rate for antibiotic prescription for acute pharyngitis has currently been established at 13%.22 Our study clearly shows that a single intervention fails to achieve this goal, since this percentage was not met either after the intervention or six years later. Based on the results obtained a multifaceted intervention should be followed by reminders targeting both clinicians and patients.

The use of rapid antigen detection tests with proper recommendation about when to use them and how to interpret their results has been associated with a reduction in the inappropriate use of antibiotics in primary care in the short term.

What this study contributesWe evaluated the impact of an intervention carried out six years earlier, without recalling when this technique was indicated or how the results were interpreted. GPs used and interpreted RADTs more appropriately immediately after the intervention than six years later.

GPs also prescribed fewer antibiotics for sore throat immediately after the intervention compared to six years after.

These findings should be taken into account when rapid tests are introduced and implemented in primary care as continuing medical education is needed to reinforce the appropriate use and interpretation of these tests in daily routine of primary care.

JMM has received financial support for two studies from GSK and Gilead respectively. CL and AM report receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics. The other authors have nothing to declare.

We wish to acknowledge the local coordinators who voluntarily participated in the study (Juan de Dios Alcántara, Marina Cid, Josep M. Cots, Guillermo García, Manuel Gómez, Gloria Guerra, M. José Monedero, Susana Munuera, Jesús Ortega, Vicenta Pineda, and Joana M. Ribas). We wish to thank all the researchers from the different Autonomous Communities in Spain, who are part of the HAPPY AUDIT 3 Collaborative Group, who have participated in the collection of the data for the preparation of this article. The nominal list of participant GPs is included in other articles previously published.