Producing biofuels such as ethanol from non-food plant material has the potential to meet transportation fuel requirements in many African countries without impacting directly on food security. The current shortcomings in biomass processing are inefficient fermentation of plant sugars, such as xylose, especially at high temperatures, lack of fermenting microbes that are able to resist inhibitors associated with pre-treated plant material and lack of effective lignocellulolytic enzymes for complete hydrolysis of plant polysaccharides. Due to the presence of residual partially degraded lignocellulose in the gut, the dung of herbivores can be considered as a natural source of pre-treated lignocellulose. A total of 101 fungi were isolated (36 yeast and 65 mould isolates). Six yeast isolates produced ethanol during growth on xylose while three were able to grow at 42°C. This is a desirable growth temperature as it is closer to that which is used during the cellulose hydrolysis process. From the yeast isolates, six isolates were able to tolerate 2g/L acetic acid and one tolerated 2g/L furfural in the growth media. These inhibitors are normally generated during the pre-treatment step. When grown on pre-treated thatch grass, Aspergillus species were dominant in secretion of endo-glucanase, xylanase and mannanase.

Plant biomass represents the largest source of renewable energy in nature. The search for renewable sources of energy requires a global effort in order to reduce the harmful consequences of global warming and to meet future energy demands.1 Second Generation biofuels are emerging as a new source of energy that is produced from biomass. The production of biofuels through advanced process technologies could aid in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. These technologies would also allow the production of renewable fuels without negatively impacting directly or indirectly on food production.2

Plant biomass is composed of lignocellulose, which generally consists of up to 45% cellulose, 30% hemicelluloses and 25% lignin.3 Cellulose and hemicelluloses are polysaccharides, while lignin is an aromatic heteropolymer binding the two polysaccharides together. Lignocellulosic biomass includes agricultural residues such as corn stover, straw, sugarcane bagasse, herbaceous energy crops, wood residues (sawmill and paper mill discards), and municipal waste.4 These materials could serve as a cheap, abundant and renewable energy feedstock that is essential to the functioning of industrial communities and critical to the development of a sustainable global economy.5

The products of cellulose and hemicellulose hydrolysis are substrates for fermentation in the production of biofuels/bioethanol. Hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass is a slow process due to the resistant crystalline structure of cellulose and the physical barrier of lignin surrounding cellulose, thus limiting the sites for enzymatic attack.6 Novel organisms are needed to provide improved enzymes and reduce the cost of converting lignocellulosic material to fermentable sugars. Also required are organisms that are able to ferment pentose sugars effectively.7 These organisms should also be able to resist inhibitors released during the pretreatment of lignocellulose.8

It is estimated that up to 70% cellulose present in natural feed is excreted by herbivores making their dung a rich source of “pre-treated” lignocellulolytic material for the isolation of lignocellulosic organisms.9 Coprophilous fungi are dung-loving and encode many enzymes needed for the hydrolysis of cellulose.10 A number of studies report the isolation of cellulase producing fungi from the dung of domestic animals, however, few studies have been done on the dung of wild herbivores. One study report the isolation of six different xylose fermenting yeasts species from the dung of a number of herbivores in Thailand.11 Other studies focused on the breakdown of elephant dung,12 the production of hydrogen using thermophilic anaerobes in elephant dung,13 the isolation of cellulolytic fungi from the dung of elephants,14 the antimicrobial compounds produced by fungi from the dung of elephant, tiger and rhinoceros15 and lastly the isolation of a β-glucosidase from a fungus associated with the rumen of buffalo.16

Yeasts currently considered for the fermentation of pentoses, especially xylose, are mainly Scheffersomyces stipitis, Kluyveromyces marxianus, Candida shehatae and Pachysolen tannophilus. Ethanol production by these yeasts utilizing xylose as carbon source is generally five times lower when compared to Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermenting glucose.17 Other factors to consider in searching for an ideal xylose fermenter are resistance to inhibitors, such as furfural and acetic acid, ability to carry out fermentation at low pH and high temperatures conditions.18

The aim of this study was to isolate xylose utilizing yeasts and cellulolytic moulds from decomposed dung of various herbivore species found in the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Yeast isolates were evaluated for their xylose fermentation capabilities, while mould isolates were screened for cellulolytic enzyme production.

Material and methodsSample collectionFifty decomposed dung samples, from wild herbivores, were collected from the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Forty dung samples were collected near the Phalaborwa rest camp and 10 samples were collected from the proximity of the Skukuza rest camp. An experienced game ranger aided with the identification of the sources of the dung samples. All samples were collected into plastic bags and processed within 48h.

Isolation of fungiApproximately 1g of the dung samples were sprinkled directly on agar plates containing 10g/L xylose, 10g/L beechwood xylan, 10g/L avicel cellulose or 10g/L locust bean gum (mannan), as a sole carbon source, 6.7g/L YNB (yeast nitrogen base, Difco), 15g/L bacteriological agar and 0.2g/L chloramphenicol to inhibit bacterial growth. The fungal isolates (yeasts and moulds) were purified through repeated streaking on fresh YM (10g/L glucose, 3g/L malt extract, 3g/L yeast extract, 5g/L peptone and 15g/L bacteriological agar) plates and pure cultures were stored on YM agar slants.

Fermentation of xylose by yeast isolatesFermentation media (20g/L xylose, 10g/L yeast extract, 2g/L KH2PO4, 10g/L NH4SO4, 2g/L MgSO4·7H2O and 0.2g/L chloramphenicol) in a 250ml Erlenmeyer flasks each containing 25ml of media was inoculated with a yeast isolate and incubated at 30°C and 150rpm for 24–120h. The above mentioned culture was used to inoculate 3×100ml of the same media in 500ml Erlenmeyer flasks to an OD600nm of 0.2 and incubated at 30°C and 150rpm for 96h. Samples of 2ml were taken every 24h. All the samples were centrifuged for 5min at 2000 x g and 4°C after which the supernatants were filtered through a 0.22μm syringe filter and stored at −20°C until analysis.

Tolerance to inhibitors and elevated temperaturesXylose fermenting yeast isolates were further tested for their ability to grow in the presence of 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 10g/L acetic acid and 1, 2, 3 and 4g/L furfural in YM agar plates. All plates were incubated at 30°C for 48h. The maximum growth temperatures for all the yeast isolates were determined using YM slants. The slants were incubated at 35, 37, 40, 42, and 45°C. The maximum temperature for growth is considered the highest temperature where growth occurred.

Production of enzyme by mould isolates on thatch grass based mediumMould isolates were screened for endoglucanase, xylanase and mannanase activity in liquid media containing 20g/L pre-treated thatch grass (Hyparrhenia sp), 4g/L KH2PO4, 10g/L (NH4)HPO4, 10g/L peptone, 3g/L yeast extract and 0.1g/L chloroamphenicol in 100ml deionized water. Pre-treatment of thatch grass was performed by grinding air dried grass to a fine powder. Dilute acid pre-treatment using 1.2% sulphuric acid was performed at 120°C for 60min at a biomass concentration of 10% (w/v). After pre-treatment, 5M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was used to adjust the pH of the thatch grass suspension to 6. Erlenmeyer flasks (250ml) containing 50ml of the thatch grass based media were inoculated with ten 4mm plugs of agar from a freshly cultured plate. All isolates were inoculated in duplicate and incubated in a rotary shaker for 5 days at 30°C and 150rpm. Samples were taken at 24h intervals.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysisXylose and xylitol levels were determined by HPLC using a Shimadzu Prominence 20 HPLC system. Samples of 20μl were injected into a Rezex RHM-monosaccharide H+ column (300×7.8mm) and eluted using water at a flow rate of 0.6ml/min. The column temperature was kept at 85°C. The separated components were detected using a Shimadzu RID10A refractive index detector. Data was processed using LC Solutions software. Sugars were identified and quantified by comparing with known standards of xylose and xylitol.

Gas chromatography (GC) analysisEthanol was analyzed by capillary gas chromatography using a Shimadzu GC2010Plus gas chromatograph on a ZB-WAX plus column (30m×0.25mm ID×0.25μm). Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 17.6ml/min. The initial column temperature was 40°C. After injection of 1μl sample, the oven temperature was raised to 140°C at a rate of 20°C/min after which it was further raised to 200°C at a rate of 50°C/min and held at this temperature for 2min. Ethanol was detected using a flame ionization detector (FID) at 255°C. The peak data was processed using GCSolutions software and ethanol concentration was calculated using ethanol standards.

Enzyme activity assaysXylanase activity was determined by mixing 45μl of 1% (w/v) birchwood xylan in 50mM citrate buffer pH 5 with 5μl of the culture supernatant (enzyme). The enzyme-substrate mixture was incubated at 50°C for 5min. The released reducing sugars were determined using a modified 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method with xylose being used as a standard.19 The amount of xylanase activity was then expressed in nkat/ml.20

Mannanase activity was assayed using 0.5% (w/v) locust bean gum in 50mM citrate buffer pH 5. This substrate was prepared by homogenizing the gum suspension at 80°C and then heating until the mixture boiled. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and left overnight with continuous stirring. The insoluble material was removed by centrifugation at 4000×g for 5min.21 The assay mixture contained 45μl of substrate solution and 5μl of enzyme solution. The enzyme–substrate mixture was incubated at 50°C for 10min. Released reducing sugars were determined by the DNS method using mannose as standards.

Endoglucanase activity was determined by mixing 25μl of 1% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) in 50mM citrate buffer pH 5 with 25μl of the enzyme solution. The enzyme–substrate mixture was incubated at 50°C for 30min. The released reducing sugars were determined by the DNS method using glucose as standards.

All enzyme activities were expressed in katals per millilitre (nkat/ml), where 1 katal is the amount of enzyme needed to produce 1mol of reducing sugar from the substrate per second.

ITS and D1/D2 sequencingAll fungal isolates were sub-cultured on YM agar at 30°C. The culture plates were sent to Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd, South Africa for ITS and D1/D2 DNA sequencing. DNA was extracted using the ZR Fungal/Bacterial DNA MiniPrepTM Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 region was amplified using PCR primers ITS-1 (5′-TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G-3′) and ITS-4 (5′-TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC-3′).22 Amplification was carried out in 25μl reactions using the EconoTaq Plus Green Master Mix (Lucingen). The following PCR conditions were used: 35 cycles including an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2min. Subsequent denaturation was at 95°C for 30s, annealing at 50°C for 30s and extension at 72°C for 1min. A final extension at 72°C for 10min was followed by holding at 4°C. Additionally, the D1/D2 domain of the 26S rDNA region was amplified using primers NL1 (5‘-GCA TAT CAA TAA GCG GAG GAA AAG-3′) and NL4 (5′-GGT CCG TGT TTC AAG ACG G-3′) as described above. DNA sequencing was done using ABI V3.1 Big dye according to manufacturer's instructions on the ABI 3500 XL Instrument.

Species were identified by searching databases using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

ResultsIn this study, 101 fungal strains, with potential application in the bioethanol industry, were isolated from the dung of various wild herbivores (buffalo, dassie, elephant, impala, klipspringer, kudu, rhino, wildebeest and zebra) from the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Cellulolytic moulds were selected based on their ability to utilize plant polysaccharides (cellulose, xylan, or mannan), while yeasts were selected for their ability to utilize xylose as the sole carbon source. This stringent selection used in the study limited the number of fungi isolated.

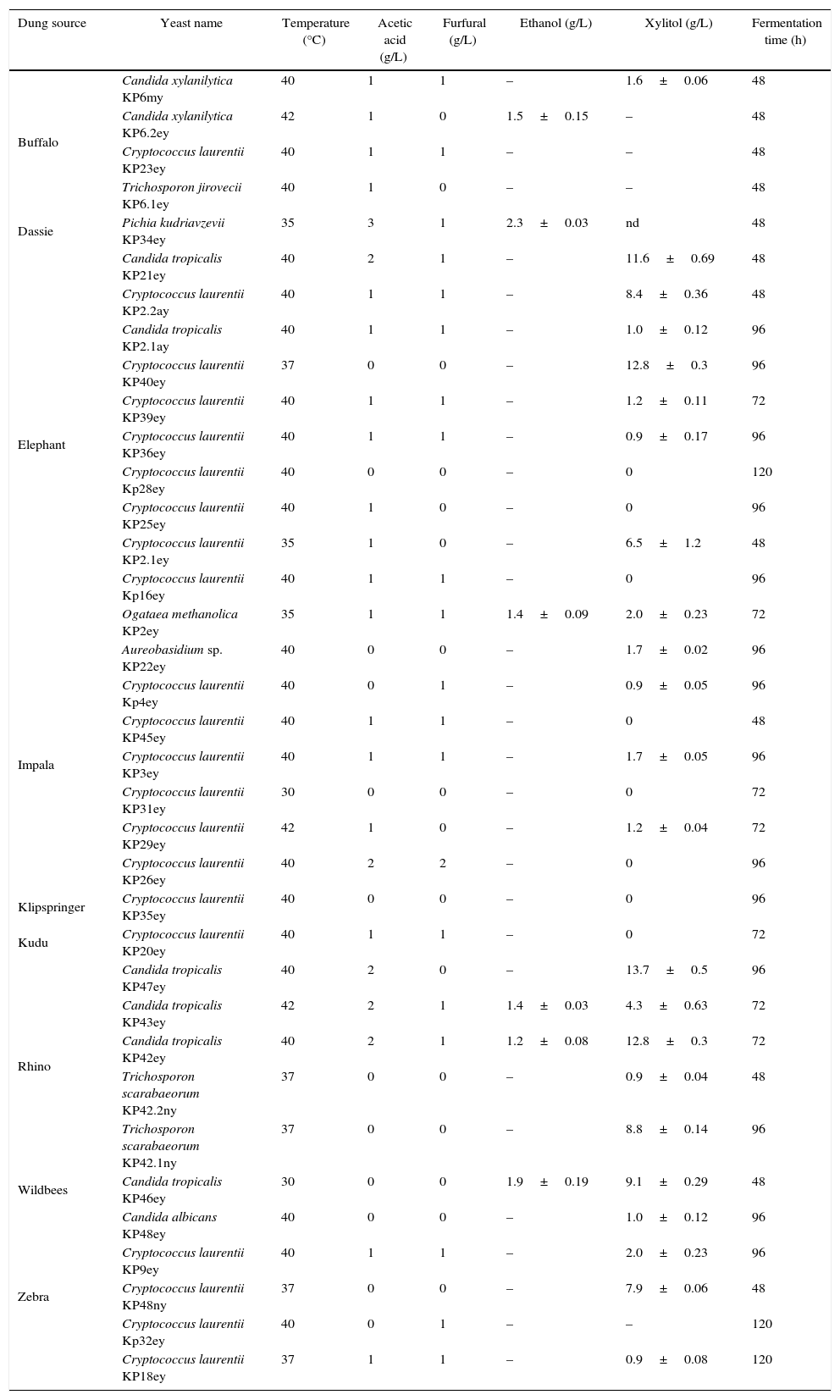

Yeasts from herbivore dungThirty six yeasts were isolated from 50 dung samples (Table 1). Fast growing yeasts were selected by picking colonies appearing after 24h of incubation at 30°C. Cryptococcus laurentii (19 strains) was the most dominant yeast in the dung samples followed by Candida tropicalis (7 strains), Candida xylanilytica (2 strains), Trichosporon scarabaeorum (2 strains), Aureobasidium sp. (1 strain), Pichia kudriavzevii (1 strain), Ogataea methanolica. (1 strain) and Trichosporon jirovecii (1 strain). It is known that C. laurentii produce mycocins in soil which could explain the abundance of these organisms compared to other species.23

Yeast isolates obtained from the dung of various wild herbivores. Isolates were evaluated for their ability to grow at elevated temperatures, in the presence of acetic acid and furfural and for their ability to ferment xylose. Ethanol and xylitol data are reported at the end of fermentation when xylose was depleted or not consumed further. Data are presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) of 3 repeats.

| Dung source | Yeast name | Temperature (°C) | Acetic acid (g/L) | Furfural (g/L) | Ethanol (g/L) | Xylitol (g/L) | Fermentation time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffalo | Candida xylanilytica KP6my | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 1.6±0.06 | 48 |

| Candida xylanilytica KP6.2ey | 42 | 1 | 0 | 1.5±0.15 | – | 48 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP23ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | – | 48 | |

| Trichosporon jirovecii KP6.1ey | 40 | 1 | 0 | – | – | 48 | |

| Dassie | Pichia kudriavzevii KP34ey | 35 | 3 | 1 | 2.3±0.03 | nd | 48 |

| Elephant | Candida tropicalis KP21ey | 40 | 2 | 1 | – | 11.6±0.69 | 48 |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP2.2ay | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 8.4±0.36 | 48 | |

| Candida tropicalis KP2.1ay | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 1.0±0.12 | 96 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP40ey | 37 | 0 | 0 | – | 12.8±0.3 | 96 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP39ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 1.2±0.11 | 72 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP36ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 0.9±0.17 | 96 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii Kp28ey | 40 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 120 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP25ey | 40 | 1 | 0 | – | 0 | 96 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP2.1ey | 35 | 1 | 0 | – | 6.5±1.2 | 48 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii Kp16ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 0 | 96 | |

| Ogataea methanolica KP2ey | 35 | 1 | 1 | 1.4±0.09 | 2.0±0.23 | 72 | |

| Impala | Aureobasidium sp. KP22ey | 40 | 0 | 0 | – | 1.7±0.02 | 96 |

| Cryptococcus laurentii Kp4ey | 40 | 0 | 1 | – | 0.9±0.05 | 96 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP45ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 0 | 48 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP3ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 1.7±0.05 | 96 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP31ey | 30 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 72 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP29ey | 42 | 1 | 0 | – | 1.2±0.04 | 72 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP26ey | 40 | 2 | 2 | – | 0 | 96 | |

| Klipspringer | Cryptococcus laurentii KP35ey | 40 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 96 |

| Kudu | Cryptococcus laurentii KP20ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 0 | 72 |

| Rhino | Candida tropicalis KP47ey | 40 | 2 | 0 | – | 13.7±0.5 | 96 |

| Candida tropicalis KP43ey | 42 | 2 | 1 | 1.4±0.03 | 4.3±0.63 | 72 | |

| Candida tropicalis KP42ey | 40 | 2 | 1 | 1.2±0.08 | 12.8±0.3 | 72 | |

| Trichosporon scarabaeorum KP42.2ny | 37 | 0 | 0 | – | 0.9±0.04 | 48 | |

| Trichosporon scarabaeorum KP42.1ny | 37 | 0 | 0 | – | 8.8±0.14 | 96 | |

| Wildbees | Candida tropicalis KP46ey | 30 | 0 | 0 | 1.9±0.19 | 9.1±0.29 | 48 |

| Zebra | Candida albicans KP48ey | 40 | 0 | 0 | – | 1.0±0.12 | 96 |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP9ey | 40 | 1 | 1 | – | 2.0±0.23 | 96 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP48ny | 37 | 0 | 0 | – | 7.9±0.06 | 48 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii Kp32ey | 40 | 0 | 1 | – | – | 120 | |

| Cryptococcus laurentii KP18ey | 37 | 1 | 1 | – | 0.9±0.08 | 120 |

Nd – not determined.

Sixteen percent of yeast isolates in this study, C. tropicalis KP42ey, KP43ey and KP46ey, C. xylanilytica KP6.2ey, P. kudravzevii KP34ey and O. methanolitica KP2ey, were able to ferment xylose to ethanol. Ethanol concentrations ranged between 1.2 and 2.3g/L (Table 1). P. Kudriavzevii KP34ey produced the highest ethanol concentration (2.3±0.03g/L).

C. xylanilytica KP6.2ey and C. tropicalis KP43ey were able to grow at 40 and 42°C, respectively. P. kudriavzevii KP34ey was able to grow at 35°C and tolerated inhibitors such as acetic acid (3g/L) and furfural (1g/L).

Twenty two yeasts produced significant amounts of xylitol during growth on xylose (Table 1). The highest xylitol concentration observed was 13.7±0.5g/L, produced by C. tropicalis KP47ey.

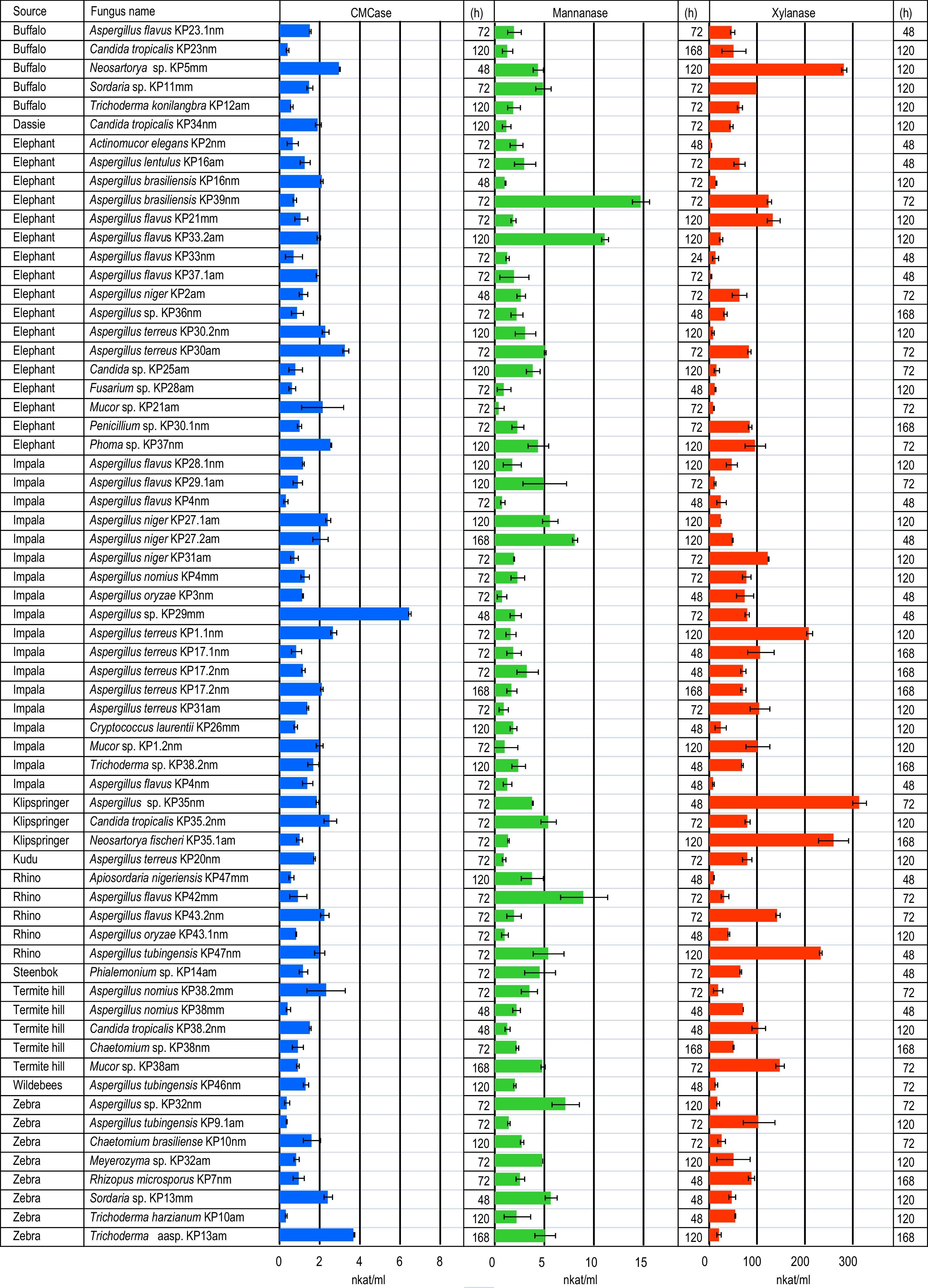

Moulds from herbivore dungA total of 65 mould isolates belonging to 16 genera, were purified and identified from media containing plant polysaccharides (cellulose, xylan and mannan) (Fig. 1). Species belonging to the genus Aspergillus were dominant among the isolates (58%). The most abundant Aspergillus species were Aspergillus flavus (11 strains), followed by Aspergillus terreus (8 strains), Aspergillus niger (4 strains), Aspergillus nomius (3 strains), Aspergillus tubigensis (3 strains), Aspergillus brasiliensis (2 strains), Aspergillus oryzae (2 strains) and Aspergillus lentulus (1 strain). Four Aspergillus isolates could not be identified to species level.

Trichoderma was less prevalent, with only 6% (4 isolates) of the fungi isolated from polysaccharide containing media belonging to the genus Trichoderma. Of the 4 isolates two were identified as Trichoderma konilangbra and Trichoderma harizianum, respectively. The remaining two Trichoderma isolates were only identified to genus level.

Thatch grass contains cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. Dry grass harvested at the end of the growing season contains approximately twice as much lignin as the live grass.24 This makes the thatch grass used in this study a very resistant carbon source that does not support growth to high cell densities. Therefore, enzyme activities obtained here are low compared to published data (Fig. 1). The highest glucanase activities were produced by Aspergillus (KP30am, KP29mm), Trichoderma (KP13am) and Neosartorya (KP5mm) spp, while the best mannanase producers were Aspergillus species (KP39nm, KP33.2am, KP42mm) (Fig. 1). The best xylanase producers belong to the genera Neosartorya (KP5mm, KP35.1am) and Aspergillus (KP35nm, KP47mm).

DiscussionEthanol is an important renewable fuel that can replace fossil transportation fuel. The use of plant biomass for the production of bioethanol requires the conversion of sugars in lignocellulose, mainly glucose and xylose into ethanol. Unfortunately, most hexose fermenting organisms, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, cannot ferment xylose. Depending on the origin, xylose can constitute as much as 30% of the fermentable sugars, in biomass. It is therefore important to ferment both glucose and xylose for efficient conversion of biomass to ethanol.

From the 36 yeasts isolated in the study, 6 (16%) were able to produce ethanol during growth on xylose. Similarly, Morais et al.25 isolated 69 yeasts from rotten wood with 14 (20%) able to ferment xylose. Rao et al.26 isolated 374 yeasts, from rotten fruit and the bark of trees and only 27 (7%) of these yeasts were able to ferment xylose. Lorliam et al.11 isolated 39 yeasts from the dung of various herbivores using xylose as carbon source. Thirty seven (95%) of these yeast isolates were able to ferment xylose to ethanol. Nineteen of these yeasts were identified as C. tropicalis. In another study by Lorliam et al.27 28 xylose utilizing yeasts were isolated from the dung of buffalo. Eleven of these isolates were identified as C. tropicalis.

P. kudriavzevii KP34ey, isolated from the dung of dassie produced the highest ethanol concentration on xylose (2.3±0.5g/L). This result compares well with that of Lorliam et al.11 where most yeasts (C. tropicalis) produced approximately 0.6g/L ethanol with Zygoascus meyerae producing the highest ethanol concentration (3.6g/L).

Enzymatic hydrolysis (saccharification) of plant polysaccharides typically occurs at around 50°C, therefore the ability of a yeast to ferment at elevated temperatures could potentially lead to reduced energy input cost. This is due to the fact that most hydrolytic enzymes function optimally at approximately 60°C, while fermentation on the other hand is typically done at 30–35°C. Hence, this requires cooling of the sugar mix before inoculation with the fermenting organism. Further, after fermentation the broth needs to be heated for recovery of the ethanol through distillation. Thus, if the fermentation temperature could be increased through the use of a thermophilic organism, a significant saving in terms of energy as well as enzyme cost would be achieved. A number of yeast isolates in this study were able to grow at temperatures above 40°C. P. kudriavzevii is known for its ability to ferment at elevated temperatures.28 Similarly, in this study P. kudriavzevii KP34ey was able to grow well at 35°C.

Furfural and acetic acid are commonly produced during the pre-treatment of hemicelluloses and have a negative effect on the subsequent fermentation.29 It is possible to remove these and other inhibitors before inoculating the fermenting organisms, however this adds to the cost of ethanol production. Ideally, the fermenting organisms should be able to resist inhibitors at levels commonly found in pre-treated material. P. kudriavzevii KP34ey isolated from the dung of dassie was able to grow in the presence of 3g/L acetic acid and 1g/L furfural. This means that P. kudriavzevii KP34ey is a good candidate for further study, since it is a good ethanol producer, it can tolerate elevated temperatures and grow in the presence of inhibitors.

A number of yeasts isolated in this study produced significant amount of xylitol during growth on 20g/L xylose. Similarly, Lorliam et al.27 reported that C. tropicalis produced 22.8g/L of xylitol during growth on 6% xylose. The presence of high concentrations of xylitol could be explained by the redox imbalance that occurs during the conversion of xylose to xylulose, especially under oxygen limiting conditions. Xylose is reduced to xylitol by xylose reductase using NADPH as cofactor. Xylitol should then be oxidized to xylulose by xylitol dehydrogenase using NAD+ as co-factor. Oxidative phosphorylation is necessary to convert NADH to NAD+. Therefore, an accumulation of NADH leads to the accumulation of xylitol under oxygen limiting conditions.30,31

There are many microorganisms including bacteria, fungi and actinomycetes able to degrade cellulose. Fungi are generally considered to be the main group of cellulolytic organisms.32,33 The majority (58%) of moulds isolated in this study belongs to the genus Aspergillus. This is not surprising considering the number of reports on Aspergillus species producing lignocellulolytic enzymes.34–37Aspergillus is a genus of filamentous fungi that contains a large number of species. It is well known for its ability to produce plant polysaccharide degrading enzymes.37–39 Aspergillli have been reported to produce the four classes of enzymes involved in the hydrolysis of cellulose, namely endoglucanases (EC 3.2.1.4), exoglucanases, including cellodextrinases (EC 3.2.1.74) and cellobiohydrolases (EC 3.2.1.91) and β-glucosidases (EC 3.2.1.21).33,40 The environmental samples screened by Ja’afaru35 yielded 43 and 41% Trichoderma and Aspergillus isolates, respectively. In contrast, the fungi identified from the tropical soil samples screened by Reanprayoon and Pathomsiriwong34 yielded only 10% Aspergillus and 3% Trichoderma.

The cellulolytic systems of the mesophilic fungus, Trichoderma reesei is one of the most thoroughly studied.33Trichoderma species are common soil inhabiting fungi with highly efficient cellulolytic systems. Numerous strains of Trichoderma reesei has been mutated to increase the production of extracellular cellulases.41

Lignified thatch grass is a difficult source of carbon for microorganisms to use, however it enabled the identification of promising lignocellulolase producing fungi in this study. The best endo-glucanase, mannanase and xylanase strains were Aspergillus sp. KP29mm, Aspergillus brasiliensis KP39nm and Aspergillus sp. KP35mm. These organisms will be investigated further as potential enzyme producers for the hydrolysis of thatch grass.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest

This research was financially supported by the University of Limpopo Research Office, the office of the Executive Dean of the faculty of Science and Agriculture, the National Research Foundation of South Africa for Grant No. 91503 and the Flemish Interuniversity Council (VLIR-UOS). We thank South African National Parks for providing access to the Kruger National Park for the collection of dung samples.

Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the author(s) and the NRF does not accept any liability in this regard.