In recent years employer branding has become increasingly important as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Companies are trying to engender affective commitment in the best employees in a global labour market. In this study, we develop and validate a multidimensional scale to measure the strength of an employee's affective commitment to the employer brand in five separate studies. In Studies 1 and 2 the Affective Commitment to the Employer Brand (ACEB) scale was developed and tested for its structure, reliability and convergent validity. Study 3 examines additional reliability and discriminant validity. Study 4 provides evidence of external validity. Study 5 examines the scale's nomological validity showing that a positive experience with the employer brand is important in making the employee develop affective commitment towards it. The limitations of the scale and the boundary conditions of its applicability are also discussed.

Employer branding is a hot topic among companies of all sizes, in all countries, and in all business sectors. The Talent Brand Index survey (LinkedIn, 2013) found that 94% of companies plan to increase or maintain their employer branding budget in 2013. In the words of Steve Barham, Senior Director of LinkedIn Talent Solutions, “The ability to better understand how your company is perceived among key professional audiences empowers you to take steps to better engage the professionals you most want to hire”.

Academics and practitioners alike agree that products and brands are among the most valuable assets of a company (Madden et al., 2006), and that the goal of branding strategies is to attract, retain and engage customers by creating brand value in the consumer's mind. Until fairly recently, only those external to the company were considered to be customers. However, the branding literature is increasingly promoting the notion that a firm's own employees are its primary customers (Edwards, 2010), the rationale being that employees are indeed (internal) customers of a valuable (internal) product: employment. Therefore, branding strategies should take into account not just external customers but also internal ones; businesses should seek to attract, retain and commit employees to the corporate mission by satisfying their needs and wants (Thomson et al., 2005; Punjaisri et al., 2008).

Satisfying needs and wants has increasingly come to mean providing emotional satisfaction. In consumer marketing, it is widely accepted that brand success relies on making promises that add value for the customer. In recent years these promises have taken on strong emotional content (Schmitt, 1999; Thomson et al., 2005; Gobé, 2010). Emotions strengthen attachment and may lead customers to buy a product, even when it carries a premium price.

Like consumer marketing, employer branding has also shifted towards the delivery of emotional benefits to achieve employee commitment (Kimpakorn and Tocquer, 2009). This affective commitment can then lead to desirable behaviours such as willingness to help or propensity for further development (Burmann et al., 2009). In this sense, consumer branding and employer branding are closely linked.

Whereas in consumer marketing, valid and reliable multidimensional scales already exist to measure consumer's affective bond to the brand, such as attachment to brands (Thomson et al., 2005), brand experience (Brakus et al., 2009) or brand love (Batra et al., 2012), in management the most commonly used measure is that of Allen and Meyer (1990). This conceptualization consists of three differentiated components: affective (desire to commit), normative (moral obligation to commit) and continuance (perceived cost of abandon) commitment and has proved efficient to measure the different types of commitment (bond) of an employee towards his/her organisation. In other words, the scale is focused on the discrimination between commitment profiles (Gellatly et al., 2006). Affective commitment in turn refers three dimensions as initially defined by its authors: “identification with, involvement in, and emotional attachment to the organization” (Allen and Meyer, 1996, p. 253). However the affective commitment mind set is measured with a single-dimension.

Since 1990, the first publication of Allen and Meyers’ scale, the relevance of affective commitment has emerged as a major issue of interest. Several authors have requested that attention should be directed at the development of measures of the relevant affective commitment mind-sets by adopting a deeper, new, more comprehensive perspective (Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Meyer and Herscovitch, 2001; Evanschitzky et al., 2006; Verhoef et al., 2002; Fullerton, 2005; Aaker et al., 2004; Mattila, 2004; Fullerton, 2005; Gustafsson et al., 2005; King and Grace, 2010).

The aim of this study is to develop a new reliable, valid and parsimonious scale to measure affective commitment that differs from previous approaches offered by literature, focusing on affective commitment to the employer brand. In this study, affective commitment is described as the degree of the emotional bond between the subject and the employer brand that encompasses enthusiasm with, and attachment to the employer brand, and creates a desire in the employee to remain in the organisation in the long term. Such an instrument may serve as an easily applicable tool for helping companies attract, retain, and appraise affective commitment to the employer brand from outstanding employees in a globally competitive landscape.

Following procedures recommended by Churchill (1979) and further developed by others (e.g. Fornell and Larker, 1981; Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Hair et al., 2005), we used qualitative and quantitative approaches to develop and validate a psychometrically reliable measure of the strength of affective commitment to the employer brand. Specifically we present here the results of 5 studies: In Study 1 we conducted a qualitative investigation of the domain of an employee's affective commitment to the employer brand, leading to the design of a pretest questionnaire to arrive at a more parsimonious set of survey items. In Study 2, we used a quantitative approach to develop and purify the scale, conducted exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and initially assessed scale reliability, unidimensionality and convergent and discriminant validity. In Study 3, using a new sample of employees, we conducted a quantitative study to assess the scale's discriminant validity with respect to potentially related constructs (e.g. satisfaction and motivation). In Study 4 we examined the stability of the scale across independent samples for further evidence of external validity. Finally, in Study 5, we examined the scale's nomological validity.

Theoretical backgroundWhat is employer branding?Ambler and Barrow (1996) coined the term employer branding to refer to all the benefits offered by a company that together create a unique employer enthusiasm in the minds of job applicants and employees, and that make them willing to join or stay with the company. These authors suggest that just like a consumer brand, an employer brand possesses a personality and an image in the mind of the labour market, which can create tight bonds between the brand and its workforce (Pitt et al., 2002). An employer brand represents a “value proposition” that individuals believe they will receive by working for a specific employer (Backhaus and Tikoo, 2004).

Recently the term has evolved to include a wide set of company activities aimed at recruiting and retaining talented professionals (Mosley, 2007; Davies, 2008). In this expanded sense, the term “employer branding” encompasses the process of building the employer brand and differentiating it to make it competitive, as well as the specific actions undertaken to attract, recruit, select, retain, recycle and release employees (Sutherland et al., 2002). Throughout the varied processes and activities collectively referred to as “employer branding”, employee commitment to the employer brand is a key indicator of the state of the relationship between the employee and the employer (Kimpakorn and Tocquer, 2009; Fernandez-Lores, 2012).

Although employer branding is still a relatively young field, several models can already be found in the literature (Backhaus and Tikoo, 2004; Mosley, 2007; King and Grace, 2010). Some researchers consider employer branding strategies to be a source of sustainable competitive advantage (Kimpakorn and Tocquer, 2009; Maxwell and Knox, 2009; Edwards, 2010), making the concept analogous to that of consumer branding (Keller and Lehmann, 2006). This group of researchers holds that employer branding is multidisciplinary, and that its aims are, externally, to make sure that the employer brand attracts talent (Miles and Mangold, 2004; Barrow and Mosley, 2005; Gavilan and Avello, 2011) and, internally, to ensure that this talent commits itself to the company (Burmann et al., 2009; Fernandez-Lores, 2012).

Conceptualization of affective brand commitmentCommitment is the foundation of all types of relationships. It has been researched from many different perspectives in many different contexts, including social exchange (Cook and Emerson, 1978), romantic relationships (Bielby and Bielby, 1989), business relationships (DeShon and Landis, 1997), teamwork (Rusbult and Farrel, 1983) and occupation (Carson and Bedeian, 1994). Therefore, the literature abounds with definitions of the term (Reichers, 1986) and different conceptualisations of its dimensionality. Early research attempted to explain commitment as a one-dimensional construct (Mowday et al., 1979; Wiener, 1982). However, the conceptualization has evolved towards a multiple dimension construct (O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986; Allen and Meyer, 1990; Meyer et al., 2002). These dimensions vary with the focus of the study (e.g. interpersonal relationships, organisation…).

Commitment has been covered comprehensively in the management literature (Becker, 1960; Mowday et al., 1979; Mobley, 1982; O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986; Mathieu and Zajac, 1990; Meyer and Allen, 1991; De Gilder, 2003). The prevailing conceptualisation of commitment to the organisation is the Three-Component Model (TCM) proposed by Allen and Meyer (1990), in which the three dimensions are affective, continuance, and normative commitment. Affective commitment is defined as “identification with, involvement in, and emotional attachment to the organization” (Allen and Meyer, 1996, p. 253). Continuance commitment leads the employee to stay because of the high costs of leaving, while normative commitment reflects the decision to remain out of a feeling of moral obligation.

Out of the three types of commitment, affective commitment has been shown to provide the greatest benefit to the organisation (Meyer et al., 2002; Meyer and Maltin, 2010). It has also been shown to be more strongly associated with desired work behaviours (Meyer and Herscovitch, 2001), such as making extra efforts to be a good organisational citizen (Ambler and Barrow, 1996; Burmann et al., 2009).

This review leads us to conclude the importance of affective commitment as a driver of desired behaviour and the appropriateness of studying it isolated from other type of commitment mind-sets in greater depth.

Differences between affective commitment to the employer brand and other constructsAffective Commitment to the Employer Brand (ACEB) should be distinguished from other constructs with which it might be correlated, such as identification, satisfaction and motivation.

IdentificationFrom Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1979), affective commitment is considered to be a key aspect of the individual's social identification. Ellemers et al. (2002) proposed that three components contribute to one's social identification: self-categorization (a cognitive awareness of one's membership in a social group), self-esteem, an evaluative component (a positive or negative value connotation attached to this group membership) and affective commitment, an emotional component. Among the three components Bergami and Bagozzi (2000) demonstrated that cognitive identification had indirect effects on citizenship behaviours through affective commitment. Although identification and affective commitment are close concepts the former is an antecedent of the latter.

SatisfactionAn employee who is affectively committed to the employer brand is likely to be satisfied, and that satisfaction may lead to emotional attachment. Nevertheless, satisfaction and affective commitment are not synonymous. Satisfaction does not automatically imply certain behaviours (Thomson et al., 2005), such as willingness to help, positive word of mouth, or a tendency to further one's career within the organisation. Satisfaction can be a momentary response; for example, it may occur immediately after an event in the workplace. It has a hedonistic component: satisfaction shares common variance with positive emotions like happiness, joy, gladness, elation, delight and enjoyment (Bagozzi et al., 1999). It also involves evaluative judgement: satisfaction in the workplace results from an employee's evaluation of how much the work environment meets his or her needs (Ramayah et al., 2001). Unlike satisfaction, ACEB is considered to be an antecedent of various brand citizenship behaviours (Backhaus and Tikoo, 2004). ACEB involves an affective promise to remain with the employer for the good and the bad. This willingness to maintain the relationship with the brand tends to develop over time as the number and variety of interactions increase. ACEB involves strong behavioural and moral (promise-based) components lacking in the concept of satisfaction.

MotivationLuthans (1998) stated that motivation is the process that awakens, activates, directs and sustains behaviour and performance. It internally encourages people towards actions that help them achieve particular task effectiveness (Weitz et al., 1986). Thus, motivation can be considered a source of intermittent inspiration for people in the workplace. When motivated, employees produce more than what is formally expected of them.

ACEB and motivation are similar in that both are affected by time and interaction, and both can strongly influence employee performance. Nevertheless, they differ in one important respect. Motivation, generally caused by a need to achieve, disappears once that need is satisfied. ACEB, conversely, involves a persistent bond with the employer that includes a promise to remain loyal in the future. Thus, the effects of motivation are much more ephemeral than those of affective commitment. The ultimate goal of commitment is to maintain the relationship itself, and it disappears only if that relationship falls apart.

SummaryIn this article, we propose a reliable and valid scale that reflects an employee's affective commitment towards his or her employer brand. We first describe how the scale was constructed on the basis of affective commitment. Second, we validate the scale's internal consistency and dimensional structure. Third, we examine reliability and demonstrate discriminant validity, showing that the scale differs from measures of satisfaction and motivation. Lastly, we examine the scale's nomological validity by investigating three antecedent experiential dimensions within a nomological network.

Study 1: qualitative study and item generationTo develop a parsimonious yet representative scale of the strength of an employee's affective commitment to the employer brand, we followed scale development procedures advocated by Churchill (1979). Our first goal was to uncover the scope of affective commitment to an employer brand by generating as many items as possible to define what employees understand to be the main descriptors of ACEB.

MethodProcedure and participantsWe conducted qualitative research based on seven focus groups involving employees of three multinational companies, in order to ensure the inclusion of diverse nuances within the affective commitment construct. Participating companies were asked to ensure that candidates for focus groups be diverse in age, gender, salary, job category and seniority in the organisation.

The number of participants in each focus group ranged from seven to nine. According to Morgan (1998) and Krueger and Casey (2000) the size of effective groups ranges from four to twelve with the ideal size being seven to ten individuals. Out of the seven focus groups, one was composed solely by managers, three were composed solely by employees, and the remaining three focus groups were composed by branch banking employees. The final sample included 27 men and 25 women.

Each focus group met for approximately two hours in a room equipped with closed-circuit cameras and sound recorders. Sessions were recorded on video and audio, allowing analysis of both cognitive and emotional responses during group interactions. Focus group facilitators were given a carefully developed script (Myers and Macnaghten, 2004). During the sessions, facilitators posed questions from the script and allowed time for free discussion. Tape-recorded discussions were transcribed.

Item generation and selectionA coding team of three students and one author identified recurring themes in the data individually (Guba and Lincoln, 1994). Then the team met to discuss their findings and shared supporting quotations. The objective at this point was to search for common criteria that allowed for the most accurate representation of each domain. In addition to this empirical qualitative analysis, we undertook an extensive literature review (Becker, 1960; Fraisse, 1964; Mobley, 1982; O’Reilly and Chatman, 1986; Shaver et al., 1987; Mathieu and Zajac, 1990; Meyer and Allen, 1991; Morgan and Hunt, 1994; Holmes, 2000; Bergami and Bagozzi, 2000; De Gilder, 2003; Kimpakorn and Tocquer, 2009; Foster et al., 2010; Kunerth and Mosley, 2011).

ResultsThe results of the qualitative analysis and literature review led to a preliminary list of 96 items grouped into the following seven initial categories: emotional attachment (25 items), enthusiasm with the brand (20), sense of belonging (10), evangelisation (14), long-term orientation (14), persistence (8), and reciprocity (5). Several marketing faculty members then evaluated the list of items for content and face validity. Items that were unclear, irrelevant to one of the domains, or otherwise open to misinterpretation were deleted (Arnold and Reynolds, 2003; Brakus et al., 2009). A total of 80 items were retained, and were distributed among the seven categories as follows: emotional attachment (24 items), enthusiasm with the brand (19), sense of belonging (6), evangelisation (9), long-term orientation (14), persistence (4), and reciprocity (4).

These items were used to develop a questionnaire capturing all identified dimensions of affective brand commitment. Items were included in random order. The questionnaire was administered to a sample of 64 employees from different companies and industrial sectors who volunteered to participate in our study. We asked them to think of their employer brand and to evaluate the extent to which the 80 items described their bond with it, using a seven-point Likert scale (1=not at all descriptive, 7=totally descriptive). Following Brakus et al. (2009), we retained the most frequently mentioned items that received mean Likert values greater than 4.5 with a standard deviation less than 2.0. This led to a final list of 55 items across six categories: emotional attachment (15), enthusiasm with the brand (11), sense of belonging (4), evangelisation (8), long-term orientation (13), and persistence (4). All items in the category of reciprocity were eliminated.

Study 2: scale purificationWe designed Study 2 to purify the scale and further reduce the number of items. Scale purification involves exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and initial assessment of scale reliability, dimensionality, and convergent and discriminant validity (Churchill, 1979; Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Hair et al., 2005). A questionnaire was generated comprising the final set of 55 items with 20% of the items negatively worded according to Weijters and Baumgartner (2012), as well as classification items such as age, income, gender, years at the company, and job description.

MethodProcedure and participantsRespondents belonging to a multinational company were instructed to indicate the extent to which the items described their commitment to the employer brand using a 7-point Likert scale (1=not at all descriptive, 7=totally descriptive). The company provided us a list of 4000 employees. We randomly selected 600 to whom we sent e-mail invitations to participate in the study. Those who accepted were sent the questionnaire by email, and 495 were returned (overall response rate of 82.5%). Data was then subjected to both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis.

Results of exploratory factor analysisExploratory analysis using principal axis factoring and Varimax rotation revealed a six-factor solution with eigenvalues greater than 1 (Hair et al., 2005). The six-factor solution accounted for 71% of total variance, but a scree plot showed only three factors to be significant (Brakus et al., 2009). To interpret the three-factor solution, we examined the items for which the main factor had loading weights greater than 0.70. Twenty-seven items met the requirement and therefore were retained in the analysis. Factor 1 captured the long-term orientation dimension (12 items); Factor 2 enthusiasm with the employer brand (7 items) and Factor 3 emotional attachment to the employer brand (8 items). To determine whether the three-factor solution was superior to the six-factor one, we repeated the exploratory factor analysis while restricting the number of factors to three. The three-factor solution accounted for 77.6% of total variance and showed a KMO measure of sampling adequacy of 0.98. A stricter loading criterion (>0.75) was used to evaluate the rotated factors. Fourteen items fulfilled the condition but none of the reverse coded items was among them (Table 1).

Study 2. ACEB dimensions revealed by exploratory factor analysis.

| Item wording | Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LT | EB | EA | |

| LT1. My commitment to

| 0.842 | ||

| LT2. I desire to work for

| 0.835 | ||

| LT3. I would feel sad if I had to leave

| 0.830 | ||

| LT4. I feel myself part of

| 0.825 | ||

| LT5. I am loyal to

| 0.773 | ||

| PERS3. I remain steadfast in my commitment to

| 0.760 | ||

| EB 1. I feel that any problem of

| 0.827 | ||

| EB 2. I feel

| 0.804 | ||

| EB 3.

| 0.799 | ||

| EB 4.

| 0.760 | ||

| EA 1. I am fond of

| 0.806 | ||

| EA 2. I have developed a strong bond with

| 0.806 | ||

| EA 3. I am emotionally attached to

| 0.791 | ||

| EA 4. I feel my ‘team colors’ | 0.764 | ||

Note: LT, Long Term orientation; EB, Enthusiasm with the employer brand; EA, Emotional Attachment.

On the basis of these results, we conducted a set of confirmatory factor analysis corresponding to the two models shown in Fig. 1. All were based on structural equation modelling to estimate parameters and compute goodness-of-fit measures using the maximum likelihood estimator (Bagozzi, 1980; Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Bearden et al., 1989). Model 1 assumed that all items loaded directly onto a single latent Affective Commitment construct. Model 2 assumed three latent variables named Long Term Orientation, Enthusiasm with the Employer Brand and Emotional Attachment reflecting a second-order factor. Both models showed that each path was significant yet the fit measures differed considerably. Model 1 showed a very low fit: χ2(77)=1544.29 (p<0.01), GFI=0.579 and RMSEA=0.205 while model 2 showed considerable better fit. However, initial inspection of modification indices (MI) revealed three items as candidates for removal: “I remain steadfast in my commitment to

These results provide evidence of the unidimensionality of the measures, with each item loading on one predicted factor (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Bollen, 1989). Reliability was assessed by calculating Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, which ranged from 0.89 to 0.93. These values are well above the recommended thresholds (Fornell and Larker, 1981; Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Hair et al., 2005) (Table 2).

Study 2. Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

| DIMENSION | Item | Standard regression weight (standard error) | t | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Term Orientation | LT1 | 0.836 (0.036) | 25.149 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.76 |

| LT2 | 0.899 (0.033) | 30.631 | ||||

| LT3 | 0.825 (0.039) | 24.454 | ||||

| LT4 | 0.918 | |||||

| Enthusiasm with the Employer Brand | EB1 | 0.793 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.74 | |

| EB2 | 0.911 (0.050) | 21.794 | ||||

| EB4 | 0.874 (0.053) | 20.626 | ||||

| Emotional Attachment to Employer Brand | EA1 | 0.871 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.72 | |

| EA2 | 0.842 (0.042) | 22.993 | ||||

| EA3 | 0.843 (0.047) | 22.990 | ||||

| EA4 | 0.835 (0.045) | 22.988 |

Convergent validity was assessed from the measurement model by determining whether each indicator estimated maximum likelihood loading on the underlying dimension was significant (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Standardised coefficients ranged from 0.793 to 0.918, and all were significant with t values above 20.626. This indicates that our measures show convergent validity.

Discriminant validity refers to the fact that each factor should capture a different dimension from the rest. The average variance extracted (AVE) for latent dimensions ranged from 0.72 to 0.76, exceeding all phi-squared correlations (Fornell and Larker, 1981). These results suggest that the measures ensure discriminant validity (Table 3).

Based on the theoretical foundation, Study 2 provides empirical evidence that the three dimensions of affective commitment to the employer brand are conceptualised as interrelated first order factors loading onto a global ACEB latent construct.

Study 3: additional reliability and discriminant validity testsStudies 1 and 2 provided a three-factor ACEB scale showing reliability and convergent and discriminant validity. To test the scale more rigorously, we compared ACEB with other scales of similar constructs (Churchill, 1979). The purpose of Study 3 was two-fold: to replicate the confirmatory factor structure on an independent sample, and to verify the scale's discriminant validity by showing that ACEB is empirically distinguishable from similar constructs such as motivation (Bakker, 2008), satisfaction (Babakus et al., 2003), and normative and continuance commitment (Meyer and Allen, 1991).

MethodProcedure and participantsUsing the same list of 4000 employee's as in Study 2, we randomly selected 250 and invited them to participate in the study by email. None of them had participated in Study 2. We sent them a questionnaire containing the 11 items of the ACEB scale, as well as the items of the scales for satisfaction, motivation and organisational commitment described below. A total of 209 completed questionnaires were returned, corresponding to an overall response rate of 83.6%.

MeasuresWe measured satisfaction (four items, α=0.79) with a metric adapted from Babakus et al. (2003), motivation (four items, α=0.90) with a metric adapted from Bakker (2008) and organisational commitment with Allen and Meyer's scale (1990), which includes its three dimensions: affective commitment (seven items, α=0.91), normative commitment (four items α=0.81) and continuance commitment (four items α=0.75). See Appendix I. Respondents expressed their agreement with these statements using a 7-point Likert scale (1=totally disagree, 7=totally agree).

Results of the measurement modelWe then conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) including the ACEB scale together with measures of satisfaction, motivation, affective, normative and continuance commitment. The model indicated acceptable fit χ2(277)=744.385 (p<0.01), GFI=0.952, NFI=0.972, CFI=0.969, IFI=0.965, and RMSEA=0.07.

Results also indicated that for all dimensions, the items loaded significantly (p<0.001) as predicted providing evidence of unidimensionality (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Reliability of the subscales was acceptable, as the coefficient alpha estimates ranged from 0.75 to 0.92 (See Appendix II).

Discriminant validity between ACEB's dimensions and normative commitment, continuance commitment, satisfaction and motivation was confirmed. The average variance extracted (AVE) for the dimensions ranged from 0.51 to 0.84, exceeding all phi-squared correlations (Fornell and Larker, 1981).

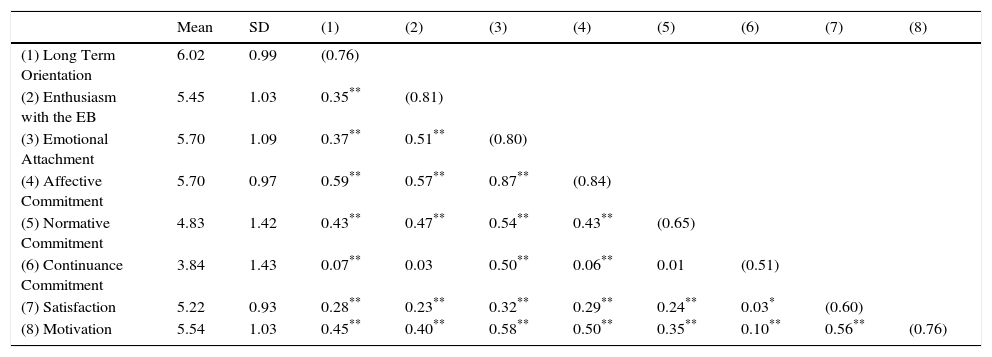

Discriminant validity between ACEB and Allen and Meyer's (1990) affective organisational commitment was not achieved. This result is consistent with the fact that the underlying conceptualization of both measures is close, although its operationalisation differs. Means, standard deviations, and squared correlation matrix are provided in Table 4.

Study 3. Means, standard deviations and squared correlations matrix.

| Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Long Term Orientation | 6.02 | 0.99 | (0.76) | |||||||

| (2) Enthusiasm with the EB | 5.45 | 1.03 | 0.35** | (0.81) | ||||||

| (3) Emotional Attachment | 5.70 | 1.09 | 0.37** | 0.51** | (0.80) | |||||

| (4) Affective Commitment | 5.70 | 0.97 | 0.59** | 0.57** | 0.87** | (0.84) | ||||

| (5) Normative Commitment | 4.83 | 1.42 | 0.43** | 0.47** | 0.54** | 0.43** | (0.65) | |||

| (6) Continuance Commitment | 3.84 | 1.43 | 0.07** | 0.03 | 0.50** | 0.06** | 0.01 | (0.51) | ||

| (7) Satisfaction | 5.22 | 0.93 | 0.28** | 0.23** | 0.32** | 0.29** | 0.24** | 0.03* | (0.60) | |

| (8) Motivation | 5.54 | 1.03 | 0.45** | 0.40** | 0.58** | 0.50** | 0.35** | 0.10** | 0.56** | (0.76) |

AVE in brackets.

The purpose of Study 4 was to confirm the degree to which the scale's findings could be replicated by other employees at different times and in other situations. Such external validity measures the generalisability of the findings (Trochim and Donnelly, 2008); a reliable scale should be stable across independent samples.

MethodProcedure and participantsFor this Study we used a professional panel data. We selected a new random sample of 700 to participate in the study. The final sample consisted of 161 employees from various companies and industrial sectors corresponding to a response rate of 23%. They filled out an 11-item questionnaire containing the ACEB scale and classification items.

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysisExploratory factor analysis using Varimax rotation revealed a three-factor solution that explained 86.6% of the variance. A measurement model was then estimated. The results indicated good fit χ2(40)=60.72 (p<0.01), GFI=0.941, NFI=0.973, CFI=0.991, IFI=0.991, and RMSEA=0.06.

Dimensionality, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity were then evaluated. As indicated in Table 5, reliability of the dimensions is acceptable as coefficient alpha ranged from 0.93 to 0.95 (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994). Composite reliability estimates (Fornell and Larker, 1981) ranged from 0.94 to 0.96, and all variance extracted estimates ranged from 0.82 to 0.86, exceeding the minimum acceptable of 0.5 (Hair et al., 2005). Convergent validity is evident since each item significantly loaded on the predicted factor with standardised coefficients above 0.8. Evidence of discriminant validity was again assessed by comparing the variance extracted estimates (AVE) with the squared phi correlations between the constructs (Fornell and Larker, 1981).

Study 4. ACEB scale.

| Item | Standard regression weight/(standard error) | t | Cronbach's Alpha | Construct Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT1 My commitment with the Employer Brand is long-term oriented | 0.929 (0.044) | 22.87 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.86 |

| LT2 I desire to work for Employer Brand for a long time | 0.971 (0.035) | 27.80 | |||

| LT3 I would feel sad if I had to leave Employer Brand | 0.874 (0.046) | 18.65 | |||

| LT4 I feel myself part of Employer Brand and I wish to remain like this in the future | 0.941 | ||||

| EB1 I feel that any problem of Employer Brand is also my problem | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.83 | |

| EB2 I feel Employer's Brand projects as mine | 0.923 (0.061) | 16.96 | |||

| EB4 Employer Brand's successes are also mine | 0.943 (0.059) | 17.58 | |||

| EA1 I am fond of Employer Brand | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.82 | |

| EA2 I have developed strong bond with Employer Brand | 0.93 (0.072) | 16.38 | |||

| EA3 I am emotionally attached to Employer Brand | 0.972 (0.068) | 17.77 | |||

| EA4 I feel my ‘team colors’ | 0.865 (0.045) | 23.37 |

The results of this study further support the structure, reliability and validity of ACEB scale.

Study 5: nomological validity of the scaleSince the importance of establishing nomological validity has been well documented (Cronbach and Meehl, 1955), we sought to investigate ACEB within a larger nomological network of theoretically related constructs. The ultimate goal of Study 5 was to measure the impact of the employer brand experience upon the employee's affective commitment towards the employer brand itself. On the basis of prior research (Brakus et al., 2009; Cacioppo and Petty, 1982; Bakker, 2008), we expected that the three dimensions of the experience with the employer brand (employee's sensory experience of the workplace, emotional experience while carrying out the work and intellectual experience of the brand values) will have a positive influence on the affective commitment to that employer brand.

MethodProcedure and participantsEmployees of private companies in various market sectors (e.g. banking, insurance, automotive industry, education, and consultancy) were invited to respond to an e-questionnaire using a 7-point Likert scale. Response data were analysed using structural equation modelling.

ACEB nomological networkExperiences, which emerge from the way in which we interact with our environment through our perceptions of physical stimuli, feelings, emotions, thoughts and actions (Dubé and LeBel, 2003), provide a powerful way to achieve competitive differentiation of goods and services (Pine and Gilmore, 1999). In marketing, the most important experiences has traditionally been buying and consuming (Holbrook and Hirschman, 1982). However, more recent research has shown that many stimuli that customers experience have its origin in the brand itself (Brakus et al., 2009). The employer brand experience encompasses the numerous stimuli that originate in the workplace where the experience occurs, ranging from the job satisfaction obtained by fulfilling tasks to the values embodied by the brand in the employee's eyes. When an employee thinks about the employer brand, his/her first thoughts are related to the way in which he/she experiences the brand in his/her day-to-day work (Kimpakorn and Tocquer, 2009). Analogous to the consumer brand experience, the employer brand experience comprises three dimensions: sensory, intellectual and emotional (Brakus et al., 2009).

Sensory experienceSensory experience with the employer brand refers to sensory stimuli supplied by the brand via the physical place where work is carried out; this constitutes the working experience (Pine and Gilmore, 1999). The physical space is where a brand's identifying characteristics are found, such as colours, smells, and music. A positive sensory employer brand experience converts the brand into a provider of sensory well-being creating an affective link between the employee and the brand. This led us to the following hypothesis:H1 Employees who have a positive sensory experience of the employer brand will demonstrate higher levels of affective commitment towards that brand.

An intellectual employer brand experience means that the employee has learned and internalised the values of the brand (King and Grace, 2010). Various studies have shown that an effective management of these values can lead employees to identify with, and commit to, the brand (Harris, 2007). Therefore, a positive experience of brand values should lead to affective commitment to the brand since the employee identifies closely with it.H2 Employees having a positive intellectual experience of the employer brand will show higher levels of affective commitment towards that brand.

The emotional component of the employer brand experience deals with the emotional experience of work. How much an employee enjoys his or her work strongly influences how he or she perceives work life and work environment. Employees who enjoy their work, work better, positively assess the quality of their work life and are usually intrinsically motivated (Csikszentmihalyi and Csikszentmihaly, 1991). This intrinsic motivation translates into a desire to tighten the link between employee and brand (Bakker, 2008). In this way, enjoying the experience of a brand acts as an antecedent to affective commitment, leading us to propose the following hypothesis:H3 Employees who enjoy their emotional experience with the employer brand will display higher levels of affective commitment towards that brand.

In order to measure sensory experience of the employer brand, four items from the brand experience scale (Brakus et al., 2009) were adapted. Seven items based on Cacioppo and Petty (1982) were used to measure the intellectual experience. The emotional experience was measured using three items adapted from the WOLF enjoyment factor scale (Bakker, 2008). Affective commitment between the employee and the employer brand was measured using the psychometrically tested and validated ACEB scale. An e-questionnaire was designed containing 25 items with responses formulated in a 7-point Likert format (1=totally disagree, 7=totally agree), as well as classification items covering company size, type of work, job level and length of time with the company. See Appendix II.

We used a new professional panel data. Simple random sampling was used to invite 850 new employees from various sectors (banking, insurance, automotive industry, education, consultancy) to participate. The final sample consisted of 181 people, corresponding to a response rate of 21.3%.

Results and discussionResults were obtained using a structural equation model using AMOS 17.0.

Fig. 2 shows the estimated structural model. The results indicated good fit χ2(266)=5689.72 (p<0.01), GFI=0.898, NFI=0.915 CFI=0. 942, and RMSEA=0.08. Cronbach's alpha values ranged between 0.94 and 0.96, suggesting high internal consistency of the latent variables. The model showed high factor loadings of the items on their respective dimension indicating a high degree of convergent validity (Hair et al., 2005). All standardised coefficients ranged between 0.70 and 0.97 and were significant.

The model also showed discriminant validity since the average variance extracted (AVE) for the six latent dimensions exceeded all phi-squared correlations (Fornell and Larker, 1981). These results support hypotheses H1–H3.

The aim of this study was to analyse the effect of the employer brand experience upon ACEB. To do this, we proposed a brand experience model comprising three dimensions: sensory, intellectual and emotional brand experience. The results obtained suggest that all three of these dimensions positively influence affective commitment. Thus, a positive employer brand experience can be important in an employee's development of affective commitment towards that brand.

The results with sensory experience highlight the importance of the workplace as a provider of sensory experiences (Pine and Gilmore, 1999), and its potential for expressing the values that the brand represents. The results with intellectual experience corroborate the findings of King and Grace (2010) concerning the importance of knowing and understanding the brand and what it stands for. The present results go even further by suggesting that the employee must accept and identify with brand values in order for them to stimulate affective commitment (Bergami and Bagozzi, 2000). The results with emotional experience reveal enjoyment to be an important driver of affective brand commitment. Employees who experience work as enjoyable feel truly alive and hope that the situation will last a long time (Bakker, 2008).

General discussionThe primary objective of this article was to develop a new measurement tool, able to reflect the strength of employees’ affective commitment towards the employer brand. Affective commitment is described as the degree of the emotional bond between the subject and the employer brand that encompasses enthusiasm with, and attachment to the employer brand, and creates a desire in the employee to remain in the organisation in the long term. Building on the premise that employees can articulate ACEB, we identified a set of 11 items to assess this type of commitment. The resulting scale reflects three factors labelled enthusiasm with the employer brand, emotional attachment to the employer brand and long-term orientation. The existence of these three factors was consistent across samples and studies.

The scale was developed in Study 1. The dimensional structure and convergent validity of the scale were assessed in Study 2. Evidence of discriminant validity was obtained in Study 3, where ACEB proved to be empirically distinguishable from other related constructs such as satisfaction and motivation. Study 4 provided evidence of external validity. Lastly, Study 5 examined the scale's nomological validity. Three experiential dimensions were investigated within a nomological network, and the results showed that a positive experience with the employer brand is important for the employee to develop affective commitment towards the brand.

The main contribution of this paper is to provide evidence that it is both possible and important to distinguish between enthusiasm with the brand, emotional attachment and long term orientations when analyzing the emotional bond between the subject and the employer brand. Affective commitment of an employee to the employer brand can be understand in light of three dimensions: “Long-Term Orientation” refers the employee's implicit intention of maintaining his or her bond with the employer remaining loyal to the brand. “Enthusiasm with the Employer Brand”, which captures the positive emotions of being energetic, active, and relatively invulnerable to trouble or worry. Enthusiasm, a subcategory of joy (Shaver et al., 1987) motivates proactive behaviours towards employer brand facing its problems, undertaking its projects and celebrating its successes. “Emotional attachment to the Employer Brand” which reflects the emotional component in the employee-employer relationship; affection, belongingness and support towards the employer brand.

Thus, the phenomenon of affective commitment to an employer brand is modelled with much more richness and diagnostic insight, when using a conceptualization that includes three different dimensions. We believe that our higher-order construct adds value over the single dimensional approach of Allen and Meyer (1990) in several ways. First it leads to a more comprehensive understanding of how employees actually experience commitment to an employer brand than prior academic studies of its individual components. Second, it allows assessing which sub-dimension might have the strongest impact on the overall strength of felt affective commitment to an employer brand.

It is also important to note that ACEB represents a complementary and compatible measurement tool to that of Allen and Meyer (1990). Whilst the Three-Component Model (TCM) proposed by these authors is useful in discriminating between the three forms of commitment – affective, normative and continuance–, ACEB would provide a deeper understanding of the affective side of commitment to the employer brand. The development of the ACEB scale satisfies the priorities promoted by the Marketing Science Institute (2014) to build up appropriate marketing metrics with adequate psychometric guarantees to evaluate the effectiveness of marketing. The ACEB scale may find immediate application in various research areas. One is in the study of brand value proposed by King and Grace (2010). Another is in the study of the relationship between employer branding and other types of branding cultivated by the organisation (e.g. consumer branding), along the lines of Moroko and Uncles (2008, 2009). The scale may prove useful for studying the relationship between an employee's experience of the employer brand and employee loyalty, as suggested by Iglesias et al. (2011). This relationship may be mediated by ACEB.

The scale should be useful for both research and practice in marketing and management. Measuring ACEB should allow a company to diagnose the state of the relationship between employees and the employer brand. In fact, ACEB may be an effective indicator of the relationship between human resource (HR) management and brand management. Today, companies and professional bodies realise that aligning the external corporate image with internal employee commitment is a key strategic opportunity, especially for those operating in highly globalised contexts. The results of the ACEB scale can serve as the basis for planning actions and communication programmes to increase the level of affective commitment and the frequency of brand citizenship behaviours (Burmann et al., 2009) promoted by employer brand, such as altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship, willingness to help, and proactivity. Practitioners, consultants and academics agree with the fact that having employees committed to the brand is vital, especially among staff whose actions directly affect customer perceptions and relationships with the company.

In order to increase ACEB, companies should promote an effective internal communication strategy, to make clear its corporate values and to provide transparency on business practices and company results. Furthermore, employees work experience emerges as a key driver of ACEB as it is expected to contribute to the development of affective commitment. The work experience includes a wide range of elements, from leadership to the atmosphere of the workplace. Indeed, everything capable to exert an impact on the employee's experience can have an effect on affective commitment becoming an ACEB driver.

Although ACEB is not a tool intended to be used directly in the recruitment process, it could be helpful in the selection of the most committed employees to assist the responsible of such process and to mentor new employees. Sumati Reddy (2009) refers the use of this strategy in the successful Ritz Carlton's hotels. Additionally, its implementation starts to be relevant since the new candidates are already part of the organisation. Therefore, either for internal recruitment processes or assessment processes, ACEB appears to be a measure with a great deal of potential.

These results are limited by several caveats. First, as Trochim and Donnelly (2008) stated, validation is a never-ending process. Thus we still need to explore the predictive validity of ACEB in greater depth. Second, although our results in Study 5 suggest that ACEB is linked with employee brand experience (nomological validity), we do not wish to suggest that sensory, intellectual and emotional experience are the only drivers of affective commitment to the employer brand. Other factors such as leadership, internal communication, corporate management, labour conciliation and teamwork should be assessed in terms of ACEB drivers. Nevertheless, even if the ACEB scale captures only some of the determinants of affective commitment, we believe it gives reliable results because it conceptualises affective commitment as the result of employee experience, which is consistent with theory.

Future work on the ACEB construct should examine drivers, effects and transculturality. It should assess the ability of HR and marketing practices to increase the ACEB level in an organisation. It would also be interesting to focus on behaviours arising from ACEB, and to explore to what extent ACEB is related to customer satisfaction. Studying the behavioural effects of ACEB would provide an additional level of insight because it would allow us to compare results based on self-reported employee behaviour (actor's perspective) with results based on managers’ or customers’ reports of employee behaviour (observer's perspective).

Given that cultural and social factors influence organisations and relationships, it would not be surprising to find that they also influence ACEB. For example, the “long-term orientation” dimension of affective commitment may have different meanings and more or less importance depending on whether the culture is future- or present-oriented (Fraisse, 1964).

We did not design our studies to examine ACEB differences between industrial sectors (e.g. manufacturing or services), or between white- and blue-collar employees. Future research should examine whether sector or job rank moderate ACEB. In fact, it may be fruitful to explore whether different levels of ACEB are suitable for different levels of management.

Lastly, future work should explore whether an employee's personal circumstances and personality traits moderate ACEB. If so, it may be possible to identify employee profiles more likely to develop affective commitment to the employer brand.

We acknowledge Santander Bank Extraordinaire Chair for its support in this research.

| Item | Mean | Std. Deviation | Cronbach Alfa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORGANISATIONAL COMMITMENT (Allen and Meyer, 1990) | ||||

| Affective commitment | ||||

| I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organisation | 6.39 | .94 | 0.91 | |

| I really feel as if this organization's problems are my own | 5.77 | 1.11 | ||

| I do not feel ‘emotionally attached’ to this organisation | 5.44 | 1.37 | ||

| This organisation has a great deal of personal meaning for me | 5.20 | 1.30 | ||

| I enjoy discussing about my organisation with people outside it. | 5.86 | 1.06 | ||

| I do not feel a strong sense of belonging to my organisation | 5.63 | 1.20 | ||

| I do not feel like ‘part of the family’ at my organisation | 5.79 | 1.23 | ||

| Normative commitment | ||||

| Jumping from organisation to organisation does not seem at all unethical to me (R) | 5.48 | 1.45 | 0.81 | |

| I do not believe that a person must always be loyal to his or her organisation (R) | 4.84 | 1.73 | ||

| One of the major reasons I continue to work in this organisation is that I believe loyalty is important and therefore feel a sense of moral obligation to remain | 4.06 | 1.74 | ||

| I think that people these days move from company to company too often | 4.93 | 1.67 | ||

| Continuance commitment | ||||

| Too much in my life would be disrupted if I decided to leave my organisation now | 4.63 | 1.17 | 0.75 | |

| I am not afraid of what might happen if I quit my job without having another one lined up | 2.97 | 1.67 | ||

| It would be very hard for me to leave my organisation right now, even if I wanted to | 3.74 | 1.81 | ||

| It wouldn’t be too costly for me to leave my organisation now | 4.02 | 1.88 | ||

| SATISFACTION (Babakus et al., 2003) | ||||

| I am satisfied with my job in “Employer brand” | 4.52 | 1.41 | 0.79 | |

| I am satisfied with my working conditions in “Employer brand” | 4.93 | 1.28 | ||

| I am satisfied with the amount of pay I receive for the work I do | 5.47 | 1.05 | ||

| Given the work I do, I feel I am paid fairly by “Employer brand” | 5.97 | .99 | ||

| MOTIVATION (adapted from Bakker, 2008) | ||||

| I get my motivation from the work itself, and not from the reward for it | 5.88 | 1.03 | 0.90 | |

| I am highly motivated to work at “Employer brand” | 5.68 | 1.21 | ||

| I work in “Employer brand” because I enjoy it | 5.55 | 1.14 | ||

| I find that I also want to work in my free time | 5.07 | 1.32 | ||

| CONSTRUCT | Item | Standardise factor loading | t-value | Cronbach's Alpha | Construct Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Term Orientation | LT1 | 0.875 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.76 | |

| LT2 | 0.824 | 17.064 | ||||

| LT3 | 0.917 | 21.546 | ||||

| LT4 | 0.875 | 18.884 | ||||

| Enthusiasm with the Employer Brand | EB1 | 0.801 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.81 | |

| EB2 | 0.940 | 21.794 | ||||

| EB4 | 0.947 | 20.626 | ||||

| Emotional Attachment | EA1 | 0.878 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.80 | |

| EA2 | 0.901 | 20.900 | ||||

| EA3 | 0.903 | 22.988 | ||||

| EA4 | 0.906 | 21.993 | ||||

| Affective Commitment (Allen and Meyer, 1990) | AF1 | 0.742 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.84 | |

| AF2 | 0.825 | 10.350 | ||||

| AF3 | 0.771 | 13.525 | ||||

| AF4 | 0.895 | 20.791 | ||||

| AF5 | 0.951 | 25.151 | ||||

| AF6 | 0.898 | 20.895 | ||||

| AF7 | 0.924 | 26.256 | ||||

| Normative Commitment (Allen and Meyer, 1990) | NOR1 | 0.755 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.65 | |

| NOR2 | 0.798 | 11.523 | ||||

| NOR3 | 0.913 | 18.300 | ||||

| NOR4 | 0.762 | 13.273 | ||||

| Continuance Commitment (Allen and Meyer, 1990) | CONT1 | 0.766 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.51 | |

| CONT2 | 0.709 | 21.336 | ||||

| CONT3 | 0.668 | 17.988 | ||||

| CONT 4 | 0.656 | 18.345 | ||||

| Satisfaction (Babakus et al., 2003) | SAT1 | 0.770 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.60 | |

| SAT2 | 0.835 | 14.659 | ||||

| SAT3 | 0.722 | 19.791 | ||||

| SAT4 | 0.679 | 11.038 | ||||

| Motivation (adapted from Bakker, 2008) | MOT1 | 0.886 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.76 | |

| MOT2 | 0.921 | 23.156 | ||||

| MOT3 | 0.815 | 17.273 | ||||

| MOT4 | 0.724 | 19.458 |

| Item | Mean | Std. Deviation | Cronbach Alfa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SENSORY EXPERIENCE (adapted from Brakus et al., 2009) | ||||

| LT1 | My workplace makes an impression on my senses | 5.42 | 1.65 | 0.94 |

| LT2 | I like my workplace | 5.45 | 1.66 | |

| LT3 | My workplace appeals to my senses | 5.15 | 1.64 | |

| LT4 | My workplace helps me do my job well | 5.10 | 1.60 | |

| INTELECTUAL EXPERIENCE (adapted from Cacioppo and Petty, 1982) | ||||

| IE1 | I take pride of the corporate values of my company | 5.55 | 1.43 | 0.95 |

| IE2 | My job makes me think | 5.29 | 1.46 | |

| IE3 | My job stimulates and challenges my thinking abilities | 5.65 | 1.34 | |

| IE4 | I enjoy my job because it engages me in a lot of thinking | 5.44 | 1.50 | |

| IE5 | I believe that if I work hard I will be able to achieve a promotion | 5.31 | 1.53 | |

| IE6 | I rely in my intellectual capabilities to develop my job | 5.80 | 1.49 | |

| IE7 | I like to learn new ways to develop my job | 5.74 | 1.48 | |

| EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE (adapted from Bakker, 2008) | ||||

| EE1 | I enjoy my job at “Employer brand” | 5.13 | 1.36 | 0.96 |

| EE2 | I have fun while working | 5.61 | 1.38 | |

| EE3 | I get pleasure from my job at “Employer brand” | 5.21 | 1.42 | |