This paper develops a bank reputation model, in an environment of economic crisis specifically marked by the nationalization of Bankia and the offer of financial rescue from the Eurogroup to Spain. From a study among four hundred bank customers, an index is developed reflecting the new configuration of reputation of the leading Spanish financial institutions and its effect on the behavior of the consumer. The conclusions of this research show that, in an environment where the financial system has been identified as the main cause of the new socioeconomic landscape, banks should focus their reputation strategies to convey reliability and to reinforce the leadership of their managers, paying special attention to consumer satisfaction and trust in order to achieve the maximum optimization of their reputation resources.

Many economic theories have helped to confirm the importance of reputation in the strategic processes of the organization, but the resources based-view (Barney, 1991) shows the ability of this intangible resource to generate superior profits, and a key sustainable competitive advantage for corporate success. Following this theory, reputations, as indicators of quality of the set of managerial actions, are a valuable resource hard to imitate, which plays a crucial role in times of crisis (Coombs, 2007). Good corporate reputations provide a reservoir of goodwill which buffers companies from market decline in times of uncertainty and economic turmoil (Jones et al., 2000), and it is quantifiable on the base of its restraining action on negative effects that could potentially spread in case of its absence (e.g. expected sales drop or time necessary to gain back the financial markets’ esteem) (Cuomo et al., 2011).

In this paper, the election of the analysis of bank reputation is conditioned by three issues that will be considered. On the one hand, in the banking sector, the service intangibility makes its assessment difficult, giving more relevance to reputation (Walsh and Beatty, 2007) whose loss may cause more harm than in any other kind of companies (Kim and Choi, 2003). On other hand, banks are facing the major challenge of resisting the negative effect that the economic crisis (also known as financial crisis) has had in the perceptions that consumers have of banks. The subprime mortgage scandal revealed that the excessive deregulation had created a parallel market, based on the fact that derived products and financial vehicles created fictitious and uncontrolled money, leading to a huge bubble that burst after the housing bubble, with devastating results for both the Spanish and world economy. And, finally, the election of this sector makes it possible to verify if the expectations and perceptions of the banks that have assumed more risks are spreading to other companies in the sector, as it is shown in the results of the study of bank reputation carried out in the United Kingdom by Burke et al. (2011).

This study also faces one of the issues that has been more controversial in measuring corporate reputation, which is its conceptualization as a reflective construct, involving the use of measurement scales that use factorial loadings to define the final structure of data without a previous theoretical basis (Dowling, 2004; Helm, 2005). In this process, essential variables containing a great part of the corporate reputation theoretical meaning can be eliminated. It is therefore necessary to analyze reputation from a multidimensional and formative approach where the dimension indicators, obtained from an extensive review of the literature, enables to extract the very essence of the concept. Considering that most reputation models use general dimensions (Schwaiger, 2004; Helm, 2005; Ponzi et al., 2011) or are focused on few specific dimensions of the study (Walsh and Beatty, 2007; Nguyen, 2010), it is advisable to consider both contributions so that the key reputation elements of the organizations analyzed are not excluded.

In this way, this paper first explores the antecedents of corporate reputation establishing a formative model of ten dimensions. These dimensions are extracted from a detailed analysis of the most relevant general and specific reputation models available in academic literature, used to measure and analyze the reputation of banks from their customers’ perspective. Then, the relationship between corporate reputation, customer loyalty and word of mouth is studied. Following this, the model is validated and applied to the four banks that lead the retail banking in Spain, in particular: BBVA, Santander, La Caixa and Bankia. Later, the implications of this current study in the field of business management are discussed. It is shown here that the measurement index extracted from this research is considerably different from the measurement proposals found in academic and professional literature. Before this circumstance, it is suggested that, in changing environments, companies should reconsider the reputation criteria that were key factors under equilibrium situations. The paper finishes by presenting the limitations of the study and suggesting future research lines related to this topic.

Theoretical foundationDefinition of corporate reputationIn the literature regarding corporate reputation, the problems derived from the complex and intangible nature of reputation are perfectly known, making it very hard to perform a conceptual delimitation, characterization and measurement (Shenkar and Yuchtman-Yaar, 1997; Deephouse, 2000; Martín et al., 2006).

Table 1 shows the definitions most cited in the academic literature, being the one by Fombrun (1996) the most highlighted because it has been used as reference definition repeatedly (Wartick, 2002; Smaiziene and Jucevicius, 2009; Walker, 2010; Lange et al., 2011). Nevertheless, according to Ruiz et al. (2012a), giving continuity to the interpretation that Fombrun (1996) gives of corporate reputation as “perceptions… of the overall appeal of the company for all its constituents”, implies measuring reputation with models that would offer too overall results to be useful in business management. Companies are more interested in learning how they are perceived by certain stakeholders and what the criteria are that condition these perceptions, instead of learning market “overall” perception of them. Therefore, this study uses the reference of the definition proposed by Ruiz et al. (2012a), who understand reputation as a perceptual representation of past actions and future prospects of a firm that describes its appeal in specific contextual circumstances, with respect to the different criteria and a specific stakeholder, compared against some standard.1 Although this is a combination of preceding definitions, it is indeed an adaptation of Fombrun's (1996) definition to the reputation definition by the American Heritage Dictionary, which was also Fombrun's (1996) reference source, although it now presents a new conceptualization more advanced and better adapted to the true essence of the concept.

Definitions of corporate reputation.

| Author(s), year: page | Definition |

| Weigelt and Camerer (1988: 443) | “A set of attributes ascribed to a firm, inferred from the firm's past actions”. |

| Fombrun and Shanley (1990: 234) | “The output of a competitive process in which items signal their key characteristics to constituents to maximize their social status”. |

| Fombrun (1996: 72) | “A perceptual representation of a company's past actions and future prospects that describes the firm's overall appeal to all of its key constituents when compared with other leading rivals”. |

| Fombrun and Van Riel (1997: 10) | “A corporate reputation is a collective representation of a firm's past actions and results that describes the firm's ability to deliver value outcomes to multiple stakeholders. It gauges a firm's relative standing both internally with employees and externally with its stakeholders. In both its competitive and institutional environment”. |

| Cable and Graham (2000: 929) | “A public's affective evaluation of a firm's name relative to other firms”. |

| Deephouse (2000: 1093) | “The evaluation of a firm by its stakeholders in terms of their affect, esteem, and knowledge”. |

| Bromley (2001: 316) | “…a distribution of opinions (the overt expressions of a collective image) about a person or other entity, in a stakeholder or interest group”.. |

| Mahon (2002: 417) | “A reckoning, an estimation, from the Latin reputatus - to reckon, to count over. The estimation in which a person, thing or action is held by others… whether favorable or unfavorable”. |

| Whetten and Mackey (2002: 401) | “Organization reputation is a particular type of feedback, received by an organization form its stakeholders, concerning the credibility of the organization's identity claims”. |

| Rindova et al. (2005: 1033) | “Stakeholder's perceptions about an organizational ability to create value relative to competitors”. |

| Rhee and Haunschild, 2006: 102) | “The consumer's subjective evaluation of a perceptual quality of the producer”. |

| Carter (2006: 1145) | “A set of key characteristics attributed to a firm by various stakeholders”. |

| Barnett et al. (2006: 34) | “Observer's collective judgments of a corporate base on assessments of the financial, social and environmental impacts attributed to the corporate over time”. |

| Smaiziene and Jucevicius (2009: 96) | “Socially transmissible company's (its characteristic’, practice's, behavior's and results’, etc.) evaluation settled over a period of time among stakeholders, that represents expectations for the company's actions, and level of trustworthiness, favorability and acknowledgment comparing to rivals”. |

| Walker (2010: 370) | “A relatively stable, issue specific aggregate perceptual representation of a company's past actions and future prospects compared against some standard”. |

| Reputation Institute (2010) | Set of perceptions about the company of the different target groups related (stakeholders), both internal and external. It is the result of the company behavior developed over time and it describes its ability to distribute value to the mentioned groups. |

With this definition, companies may have as many reputations as groups of stakeholders and different reputations for the different criteria. From this conceptualization, reputation is measured as a multidimensional construct that provides “specific information” where reputation programs will be developed, focusing on one or several aspects that the firm is interested in enhancing among its different interest groups.

From this conceptualization of corporate reputation, it is likewise possible to distinguish reputation from the concepts of identity and image, which far from being synonyms for reputation would be related concepts. Thus, “the organization (past) actions, influenced by the company identity (conveyed through communications, employers and other company events) would become their external images (corporate image), that generates expectations (future) for company's performance, behavior and ethics, which are contrasted by individuals over time with their experiences and other actions of the company, giving rise to a reputation” (Ruiz et al., 2012a: 14). According to this concept of reputation, a firm can create its image immediately by media campaigns, whereas its reputation takes shape over time as stakeholders acquire direct or indirect experiences with the organization (Rindova, 1997), so that the good reputation is the final result of the image construction process (Balmer, 2009) and it depends on the consonance between the company's apparent behavior and the experiences of the stakeholders (Hansen and Sand, 2008).

Multidimensional concept of corporate reputation: dimensions and consequencesFrom the analysis of the corporate reputation models with greater dissemination, it is concluded that there is not an agreement on the concept dimensions (Gotsi and Wilson, 2001) and that most of them follow general approaches, without distinguishing among sectors or stakeholders. They use the same criteria with the same relative importance to measure the reputation of a bank or of a dairy products company; as well as to measure reputation among expert publics (managers or analysts) and among consumers who do not have technical data related to the organization. Before this situation, it is necessary to include in the theoretical review of those less popular models but which are closer to this work.

In this way, the dimensions of reputation used in this study are extracted from the fusion of the dimensions collected from the general reputation models and specific reputation models designed to measure the reputation of service companies among their consumers (Table 2). Among the general models used, those more widespread stand out, such as the Rep Trak Pulse by the Reputation Institute, Most Admired Companies by Fortune 1000 magazine and the Reputation Quotient by Harris Interactive consulting. The main contribution of the specific models is extracted from the scales of Walsh and Beatty (2007) and Walsh et al. (2009a,b), who follow methodological approaches similar to this study's. Special attention is also paid to the models designed to measure the perceptions that bank customers have of their banks (Chen and Chen, 2009; Akdag and Zineldin, 2011), among which the ones proposed by the works carried out among bank customers in certain Spanish regions are included (Flavián et al., 2004, 2005; Bravo et al., 2009b; García de los Salmones et al., 2009; Bravo et al., 2010a). It is noted that all studies use samples that precede the beginning of the crisis or the deterioration of the effects of the Spanish recession from the fourth quarter of 2008.2

General and specific models of corporate reputation, literature.

Reputation monitors of prestigious institutions: Fortune's Most Admired Companies by Fortune magazine. Merco Companies, Merco Financial Brands and Merco Tracking by Villafañe & Asociados consulting. Rep Trak Pulse by Reputation Institute consulting. Reputation Quotient by Harris Interactive consulting.

After this merger process of general and specific models, ten dimensions of bank reputation are obtained: eight cognitive dimensions and two emotional dimensions. They are contrasted by means of the individualized and detailed study of the literature related to each one of them (Table 3), which makes it possible to verify them theoretically and formulating the hypotheses of this research.

Dimensions of banking reputation, literature.

Among the cognitive antecedents of reputation, the appeal of the offer of products and services appears in most studies (Newman, 2001; Nguyen and LeBlanc, 2001; Roberts and Dowling, 2002; Vitezic, 2011) as the most important attribute of corporate reputation, especially from customers’ perspective. According to Shapiro (1983), a firm has good reputation if consumers think that its products are of good quality. A quality offer is a key factor for reputation since it allows the companies to show credibility and to gain the trust of their stakeholders (Fombrun, 1996). Even Lewis and Soureli (2006) suggest that in the banking sector the assessment of this dimension, explained by issues related to quality and the variety of products/services and the conditions of sale, is so important that it might eventually cast a “halo” effect on the other dimensions of corporate reputation.

The dimension that presents aspects related to customer care and the interactions with the employees appears as the heaviest antecedent in the analysis of reputation of services companies among their customers (Walsh and Wiedmann, 2004; Flavián et al., 2005; Walsh and Beatty, 2007; García de los Salmones et al., 2009; Walsh et al., 2009a,b). Most general models do not integrate this dimension since their studies includes public that never had a direct relationship with the organization, and that could not make a personal assessment of the aspects related to customer care, such as friendliness and employees’ skills. According to Hardaker and Fill (2005) and Nguyen (2010), customer care becomes a key component for the development of identity and reputation of services organizations, since it is here where care is really taken and the relationship is born.

The degree of innovation of a firm is a dimension of growing importance in the measurements by Rep Trak Pulse from its first study in 2006. Its analysis is included in most specific models (Walsh and Beatty, 2007; Bravo et al., 2009b; Walsh et al., 2009a,b; Akdag and Zineldin, 2011), not as an independent dimension but as one more aspect of the assessment of the offer or services provided. The innovative spirit is associated with the organization identity and, therefore, it is present from the beginning of the formation process of reputation. The preeminence or notoriety of the company, that have been considered as an antecedent of its reputation (Rindova et al., 2005), will be increased if it introduces new products in a consistent and successful way, what will boost its relevance among consumers and their favorable predisposition toward the company (Henard and Dacin, 2010).

As it is shown in Table 2, the employer branding dimension is present in the general and specific models. It makes reference to the perceptions that customers have on how the firm and managers deal with the employees and safeguard their interests, as well as on the expectations that customers have about the employees’ competence. Several authors identify the strategic role of this dimension as protector of corporate reputations (Sánchez and Barriuso, 2007; Burke et al., 2011), whereas De la Fuente and De Quevedo (2003) confirm that the way the company treats the employees affects the perceptions of the rest of stakeholders. From the Theory of Signs, high performance training based on talent appeal and workers’ commitment would be signals sent to the outside by the organization in order to create the impression of reputable employer (Martin and Groen-in’t Woud, 2011).

The integrity dimension is understood as the degree of responsibility, transparency, ethics and honesty practiced by organizations, which constitute the main principles to increase reputation among their stakeholders (Vitezic, 2011). This dimension extracted from the general and specific models shown in Table 2, is also analyzed as indicator of other dimensions in the specific models of Bravo et al. (2009b) and García de los Salmones et al. (2009). According to Hill and Knowlton (2004), managers highlight the attitude of corporate governments as one of the most influential factors in business reputation. Considering that, furthermore, misconduct and lack of transparency have been identified as the main causes of the world economic/financial crisis, it can be stated that, now more than ever, the integrity practiced by the governments of financial institutions form a critical dimension of the perceptions that customers have of banks (Delgado et al., 2008).

Leadership, referring to the actions carried out by the leaders of the company, is a dimension collected by the main general models. Although it is less present among specific models, concepts related to leadership are analyzed as one more aspect of the other dimensions in the scales of Walsh and Beatty (2007), Bravo et al. (2009b) and García de los Salmones et al. (2009). According to Khurana (2002), the expected skills of a good leader have been transformed and they no longer depend on professional excellence and honesty but on charisma and leadership skills. The main appeal of a firm leader, being considered as an intangible asset, is that it can be more powerful by implementing a process of leadership management that gets to boost the top executive's reputation and transfer it to the organization (Sotillo, 2010), setting up a process of “reputation transfer” from the leader to the company (Gaines-Ross, 2003).

The reliability and financial strength dimension is present in most general and specific models, and it makes reference to the abilities that firms have to generate benefits in order to guarantee the survival and growth of the business, as well as to guarantee customers’ deposits in the case of banks. Positive economic indicators predispose the public to a more positive assessment of the company (De Quevedo, 2003; Rose and Thomsen, 2004) since they determine the sector dominance and prestige (Lease et al., 2000). High profitability of the firm in the past will lead economic agents to anticipate a high creation of value in the future that will favor their expectations of satisfaction of their demands and, furthermore, the corporate reputation consolidation (Delgado et al., 2008). However, for the public who is not informed, such as consumers, financial data do not acquire such an important role and different indicators are used in order to intuit the economic health of the firm, such as: the company position in relation to its competitors (Walsh and Beatty, 2007), its solidity or solvency (García de los Salmones et al., 2009), its recognition worldwide (Schwaiger, 2004) or its future perspectives (Bartikowski and Walsh, 2011). This kind of information, more than indicators of the financial profitability of the organization, reflect its reliability among the public that is not informed who, to a great extent, intuits this information from the advertising received by the organizations and the word of mouth.

The dimension related to companies’ social action, which includes their social, philanthropic and environmental activities, is present in all reputation general models and in most specific ones. It is a concept of growing importance in the mind or emotions of consumers who want to see companies acting as active and responsible citizens (McWilliams et al., 2006). Thus, a good ongoing social action adapted to the different institutional contexts would consolidate the legitimization and corporate reputation (De Quevedo et al., 2007). The study of Mattila et al. (2010) demonstrates that messages of social action may mitigate the negative effects of the financial crisis in consumers’ perceptions, in the same way that in the past low reputation, such as oil and tobacco companies, had managed to reestablish their image from advertising their social action projects.

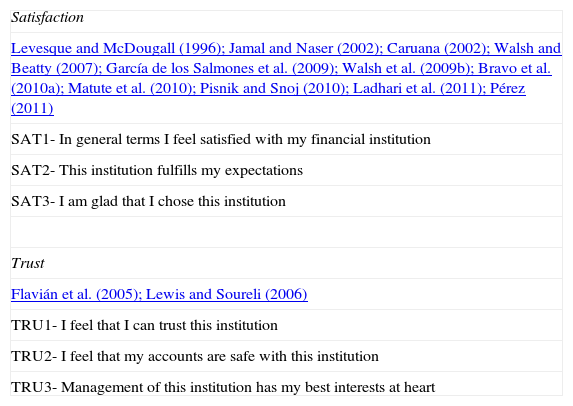

Although most business reputation models use exclusively cognitive criteria, there is a theoretical support large enough (Levesque and McDougall, 1996; Dowling, 2001; Roberts and Dowling, 2002; Rose and Thomsen, 2004; Hansen and Sand, 2008; Ladhari et al., 2011) that considers emotional dimensions: satisfaction and trust, as antecedents of reputation, especially when the customer is the analysis group. Customers have had direct experiences with the organization that enable them to compare the image that they had of it and to configure business reputations (Giogia et al., 2000). In this way, the higher or lower level of satisfaction of direct and indirect experiences of customers with the company, and the degree of trust acquired through them, are antecedents of corporate reputation (Walsh et al., 2009b). The empirical confirmation of these two relationships together can be found in the model of Walsh et al. (2009b), whereas in the model of Helm et al. (2010) it is demonstrated for the case of satisfaction, and in the models of Newell and Goldsmith (2001) and Ponzi et al. (2011) for the case of trust. This last one, based exclusively on stakeholders trust, was later validated by Wilczynski et al. (2009).

From a review of the literature, the following hypotheses are formulated about the formation of bank reputation:Hypothesis 1 Favorable characteristics of the offer have a direct effect on the reputation of financial institutions among their customers. Favorable customer care has a direct effect on the reputation of financial institutions among their customers. Financial institutions innovation has a direct impact on the reputation of financial institutions among their customers. Financial institutions employer branding has a direct effect on their reputation among their customers. Financial institutions integrity has a direct effect on their reputation among their customers. Financial institutions leadership has a direct effect on their reputation among their customers. Financial institutions reliability has a direct effect on their reputation among their customers. Financial institutions social action has a direct effect on their reputation among their customers. The satisfaction that customers feel from their relationship with financial institutions has a direct effect on their reputation among their customers. The trust that customers have in their relationships with financial institutions has a direct effect on their reputation among their customers.

Regarding the consequences of corporate reputation, although little research has focused on its analysis, the studies carried out by Walsh et al. (2009b) and Bartikowski and Walsh (2011) demonstrate empirically the direct relationship between corporate reputation and customer loyalty. According to theories of cognitive consistency, people maintain a psychological harmony among their beliefs, attitudes and behaviors; therefore, when customers give a good reputation to a services company, they will be probably committed to it and they will intend to continue interacting with it, or carrying out other actions in its favor (Zeithaml et al., 1996; Bettencourt, 1997). There has been evidence showing that the increase in profit resulting from a five percent increase in customer retention varies between 25% and 85% (Ladhari et al., 2011) and that to retain a customer can be up to ten times cheaper than achieving a new one (Heskett et al., 1990). Along with loyalty, word of mouth is the most common consequence associated with reputation (Walsh and Beatty, 2007; Walsh et al., 2009b). Some authors have considered word of mouth as a much more powerful strength than traditional marketing tools (Silverman, 2001) by influencing future purchasing decisions and by helping to attract new customers, especially when the service provided poses a high risk for them (Molina et al., 2007). On the basis of the findings reported in the previous studies, the following hypotheses are raised about the consequences of bank reputation:Hypothesis 11 Financial institutions reputation among their customers has a direct effect on the loyalty of their customers. Financial institutions reputation among their customers has a direct effect on customers’ positive word of mouth.

A multidimensional construct consists of heterogeneous aspects and each one makes a unique contribution. Therefore, it is more appropriate to cope with this type of constructs from the formative perspective (Gómez et al., 2013), where dimensions are causing the concept. According to Helm (2005), if reputation was to be conceptualized as a reflective construct, it would imply supposing that its dimensions (e.g. product quality or employees care) would be effects of the construct. In other words, company reputation would determine the quality of its products or how employees are taken care of, and not the other way as it happens actually. Furthermore, if reputation was to be modeled as a reflective construct, the different dimensions would be strongly correlated among them, that is to say, an improvement in the product quality would be accompanied by a better care of the employees or a greater contribution to environmental preservation. However, it is not feasible to assume that this is like this, since an institution, by means of its employees, can actually provide an excellent care and service, regardless of not being so worried about environmental issues.

In this study, the reputation of banks is conceived as a second order multidimensional construct that is integrated by cognitive dimensions (modeled as formative constructs) and emotional dimensions (measured in a reflective way). Following the criterion of Dowling (2004), Schwaiger (2004) and Helm (2005), cognitive dimensions (offer, customer care, innovation, employer branding, integrity, leadership, reliability/financial strength and social action) are formed by their indicators that, at the same time, also contribute to reputation formation. The formative-formative approach differs from the one used in most models of reputation measurement because, although these use second order formative approaches, the process followed to identify the indicators of each dimension is the typical of the reflective models (Dowling, 2004; Helm, 2005). From an exploratory factorial analysis, the underlying structure is obtained among a large number of variables, without a previous theoretical basis but using factorial loadings to define the data final structure (Hair et al., 2006). This process of identifying dimensions implies that essential indicators can be removed in the determination of that particular dimension of corporate reputation, for not having an optimal factorial loadings or for bringing together in an only one factor variables that do not have a theoretical correspondence among them (Blázquez, 2009). In order to avoid this problem, the indicators of the cognitive dimensions in this study, extracted from a wide review of the reputable literature, are determined in the basis of a formative approach.

Emotional dimensions (satisfaction and trust) are related in a reflective way to their indicators and in a formative way to reputation, following the most commonly used criterion in the studies included in the analysis of these concepts in relation to reputation.

In this paper, reputation global indicators are also used, since to be able to estimate second order constructs it is necessary for constructs to be directly measured by indicators to achieve an optimal identification of the model.

Furthermore, and following the practice found in the existing literature, outcome variables (loyalty and word of mouth) are also measured as first order reflective constructs, in such a way that every item reflects the latent construct.

Companies in the studyConsidering the volume of assets as an indicator of the size of the institutions and taking into account that the size of the organizations is one of the variables that has a stronger effect on their reputation, this research is addressed to the study of the reputation of the four leading financial institutions in the national scene (Graphic 1): BBVA, Santander, La Caixa and Bankia. In this way, the possible bias derived from size differences or market power of the analyzed institutions is minimized. Additionally, given that they are two of the main banks and two of the main savings banks,3 qualitative differences that could derive from their condition (bank or savings bank) are compensated.

Largest financial institutions in Spain by assets. Total June, 2012. Million euros. Data extracted from Invertia.com. Available at http://www.invertia.com/noticias/articulo-final.asp?idNoticia=2657129 (28.02.14).

The election of the customers of the different firms as target group is determined by their higher knowledge of the organizations, acquired through their direct experiences with them, which enable them to make more consistent judgments about the different criteria used for their assessment. According to Dowling (2001), an important determinant of the reputation that a person has of a company is the relationship that this person has with it, and customers are more likely to have a relationship with companies. Moreover, the judgments that customers make about firms come into being as purchasing decisions, financial investment decisions, the election of a certain company where to work or other decisions that are key factors to the survival and successful development of companies (Walsh and Beatty, 2007).

For this study, four hundred bank customers were selected, one hundred from each of the four institutions under analysis (sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Appendix 1). In order to achieve a representative sample and the utmost rigor when performing the fieldwork, it was necessary to hire the services of the company Netquest,4 which is specialized in carrying out studies of online market that is the most commonly used system for gathering information in order to study reputation, both in academic and business fields. Table 4 shows the technical datasheet of the research.

Technical specifications of the survey.

| Universe | Financial institutions customers older than 18: Santander, BBVA, La Caixa and Bankia |

| Geographical area | Spain |

| Sample size | 400 valid questionnaires |

| Sampling error | ±4.9%, confidence level of 95%; p=q=0.5 |

| Sampling method | Stratified random sampling |

| Sample design | Online panel by Netquest online Panel |

| Field work | From 8th to 27th of June, 2012 |

Following the criterion of Jamal and Naser (2002), the relationship of the sample customers with their main bank must exceed three years; furthermore, they must have more than three contracted products and they cannot be either shareholders or bank workers. The first two conditions guarantee the strength of the experience of the customer with the institution and the third one limits the possibilities that the respondent has privileged information that does not concern customers in general.

Questionnaire and measurement scalesThe questionnaire is divided into three main parts. The first section verifies the suitability of the respondent as part of the sample (time as a customer of the institution, status of shareholder or bank worker and contracted products). The second part includes questions addressed to assess the reputation of the main financial institution and of the outcome variables.

In order to guarantee the content validity of the measurement index in this study, a detailed analysis of all the scales used in order to measure corporate reputation along with each of their most commonly associated dimensions is carried out. The conclusions of this analysis are contrasted with the results extracted from the review of the scales specially developed to measure bank customers’ perceptions. Taking into account that reputation is different among the different stakeholders and different criteria, and that the sector where the company interacts also conditions the relevance of reputation attributes in a qualitative and quantitative way (Ruiz et al., 2012b), the purpose of this study is to develop a highly accurate index that guarantees the identification of the dimensions that determine indeed the reputation of the institutions analyzed.

For the identification of the cognitive variables, a methodology focused on the review of the literature and subsequent refinement by experts has been followed. After the exploratory analysis of general and specific items of corporate reputation, a set of 74 variables is extracted. The first refinement developed with 10 strategy and marketing teachers makes it possible to identify highly redundant items and, as a result of it, the questionnaire is reduced to 62 variables. Then, 7 experts, 20 bank professionals, a stock expert and 20 bank customers are interviewed. At this stage, the questionnaire is reduced to 51 items grouped in 8 cognitive dimensions (Appendix 2a). The two emotional dimensions are assessed by reflective scales extracted from the main reputation studies in the banking sector (Appendix 2b).

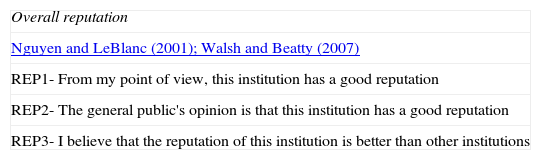

In order to measure global reputation, which enables to check the external validity of the dimensions that form bank reputation, and behavioral intentions (loyalty and word of mouth), reflective scales were used, consisting of three items selected from other reputation studies (Appendices 2c and 2d). All the indicators were measured on ten-point Likert-type scale, from 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). The reason why the scale of 0 to 10 is selected is because non-professional stakeholders are more familiar with it for their everyday evaluations.

The third section of the questionnaire raises the questions related to the sociodemographic information of the respondents, in particular: sex, age, marital status, education, working status and income level.

Data analysis and findingsEvaluation of measurement modelThe measurement instrument (reliability, convergent and discriminant validity) has been validated by the partial least squares (PLS), technique especially appropriate to analyze formative constructs (Chin, 1998a,b). The model has been estimated by using SmartPLS 2.0 (Ringle et al., 2005) and the parameters significance has been obtained by bootstrapping, randomly generating 500 sub-samples, with the same size as the original sample (400 in total: BBVA customers: 100; Santander customers: 100; La Caixa customers: 100; Bankia customers: 100).

Concerning psychometric properties, the calculated indicators of reflective constructs show excellent reliability levels (Table 5). All the indicators show values higher than 0.85, over 0.7 proposed both for Cronbach's alpha (Hair et al., 2006) and composite reliability index (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The average variance extracted (AVE) values are significantly different from zero and higher than 0.6, guaranteeing the convergent validity of the measurement reflective model (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988).

Measurement model: Assessing the instrument.

| Dimension/construct | Indicator | Loading | Weight | t-value (Bootstrapping) | ∞ Cronbach | CR | AVE |

| Offer | OFF3 | 0.448*** | 7.06 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| OFF4 | 0.132* | 1.80 | |||||

| OFF5 | 0.282*** | 4.87 | |||||

| OFF8 | 0.293*** | 3.84 | |||||

| Customer care | CTC3 | 0.210** | 2.48 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| CTC6 | 0.190** | 2.01 | |||||

| CTC9 | 0.403*** | 3.88 | |||||

| CTC11 | 0.141** | 1.96 | |||||

| CTC12 | 0.268*** | 4.05 | |||||

| Innovation | INN1 | 0.465*** | 6.65 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| INN3 | 0.389*** | 5.16 | |||||

| INN4 | 0.248*** | 4.01 | |||||

| Employer branding | EBR1 | 0.554*** | 8.84 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| EBR2 | 0.239*** | 3.86 | |||||

| EBR5 | 0.260*** | 3.85 | |||||

| Integrity | INT1 | 0.657*** | 10.70 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| INT3 | 0.412*** | 6.53 | |||||

| Leadership | LEA2 | 0.543*** | 10.29 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| LEA3 | 0.518*** | 9.75 | |||||

| Reliability and financial strength | REL2 | 0.365*** | 5.97 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| REL6 | 0.179*** | 3.76 | |||||

| REL7 | 0.418*** | 8.98 | |||||

| REL10 | 0.195*** | 3.06 | |||||

| Social action | SA1 | 0.241*** | 2.91 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| SA2 | 0.294*** | 2.97 | |||||

| SA3 | 0.566*** | 6.57 | |||||

| Overall reputation | REP1 | 0.971*** | 212.79 | 0.969 | 0.980 | 0.988 | |

| REP2 | 0.976*** | 306.48 | |||||

| REP3 | 0.963*** | 190.11 | |||||

| Satisfaction | SAT1 | 0.976*** | 255.94 | 0.973 | 0.982 | 0.948 | |

| SAT2 | 0.974*** | 150.12 | |||||

| SAT3 | 0.970*** | 248.76 | |||||

| Trust | TRU1 | 0.950*** | 160.63 | 0.926 | 0.953 | 0.871 | |

| TRU2 | 0.925*** | 87.78 | |||||

| TRU3 | 0.923*** | 117.34 | |||||

| Loyalty | LOY1 | 0.955*** | 173.43 | 0.929 | 0.955 | 0.877 | |

| LOY2 | 0.956*** | 141.43 | |||||

| LOY3 | 0.895*** | 75.09 | |||||

| Word of mouth | WOM1 | 0.983*** | 433.94 | 0.982 | 0.988 | 0.966 | |

| WOM2 | 0.975*** | 266.73 | |||||

| WOM3 | 0.988*** | 545.24 | |||||

CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; N/A, not applicable.

The discriminant validity is verified by testing that the AVE for each construct is higher than the square of the correlations among each pair of constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Moreover, Smart PLS 2.0 provides an indicator's cross-loadings with every construct, showing that no indicator has higher loadings over another different construct in association (Götz et al., 2010). Both criteria have indicated sufficient discriminant validity (Table 6).

Measurement model: Discriminant validity.

| OFF | CTC | INN | EBR | INT | LEA | REL | SA | REP | SAT | TRU | LOY | WOM | |

| OFF | N/A | ||||||||||||

| CTC | 0.401 | N/A | |||||||||||

| INN | 0.261 | 0.561 | N/A | ||||||||||

| EBR | 0.433 | 0.486 | 0.433 | N/A | |||||||||

| INT | 0.405 | 0.573 | 0.608 | 0.562 | N/A | ||||||||

| LEA | 0.455 | 0.569 | 0.599 | 0.465 | 0.620 | N/A | |||||||

| REL | 0.590 | 0.500 | 0.424 | 0.535 | 0.591 | 0.615 | N/A | ||||||

| SA | 0.368 | 0.390 | 0.299 | 0.412 | 0.368 | 0.409 | 0.455 | N/A | |||||

| REP | 0.139 | 0.301 | 0.427 | 0.238 | 0.441 | 0.323 | 0.214 | 0.138 | 0.942 | ||||

| SAT | 0.332 | 0.429 | 0.382 | 0.449 | 0.482 | 0.421 | 0.446 | 0.286 | 0.380 | 0.948 | |||

| TRU | 0.319 | 0.373 | 0.362 | 0.469 | 0.500 | 0.406 | 0.421 | 0.332 | 0.353 | 0.623 | 0.871 | ||

| LOY | 0.345 | 0.373 | 0.481 | 0.501 | 0.564 | 0.468 | 0.455 | 0.315 | 0.381 | 0.614 | 0.540 | 0.877 | |

| WOM | 0.342 | 0.430 | 0.422 | 0.488 | 0.534 | 0.462 | 0.460 | 0.315 | 0.377 | 0.665 | 0.560 | 0.729 | 0.966 |

OFF, Offer; CTC, Customer care; INN, Innovation; EBR, Employer branding; INT, Integrity; LEA, Leadership; REA, Reliability and financial strength; SA, Social action; REP, Reputation; SAT, Satisfaction; TRU, Trust; LOY, Loyalty; WOM, Word of mouth.

Principal Diagonal, Average variance extracted; Below the diagonal, squared correlations between constructs.

N/A, not applicable for formative latent variables.

In formative constructs, multicollinearity (Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability) is an undesirable property as it causes estimation difficulties. These estimation problems arise because a multiple regression links the formative indicators to the construct. Highly intercorrelated indicators are almost perfect linear combinations and, therefore, they are quite likely to contain redundant information. Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer (2001) suggest the indicator elimination based on the variance inflation factor indicator (VIF), which assesses the degree of multicollinearity. VIF analysis results show that only 31 items, out of 51 which composed the initial index, are below 3.3, the strictest heuristic value at the point where some problems of collinearity start to emerge for formative measures (Petter et al., 2007). The results suggest no multicollinearity in the indicators that create bank reputation. The significance and loadings of indicators were tested by t-value. The results show that 5 indicators should be removed and, after this refinement process, the final 26 indicators of the bank reputation index were extracted (Table 7).

Indicators of the dimensions: collinearity testing.

| Dimension/indicator | COD | VIF |

| Offer | ||

| Offers a wide and complete range of products | OFF3 | 2.266 |

| Keeps its customers well informed of their accounts and of new products | OFF4 | 2.357 |

| Offers the most attractive conditions for savings and debt products | OFF5 | 2.362 |

| Solves problems quickly | OFF8 | 2.368 |

| Customer care | ||

| Has personnel who anticipates my needs | CTC3 | 2.594 |

| Its personal is expert | CTC6 | 2.576 |

| His personnel gives a clear and detailed view of pros and cons regarding products and services | CTC9 | 3.253 |

| Its telephone banking service is good | CTC11 | 1.926 |

| Its online service is good | CTC12 | 1.693 |

| Innovation | ||

| Tends to innovate rather than imitate | INN2 | 2.797 |

| Tends to be the first to introduce new products and services | INN3 | 2.731 |

| Its equipment and technology are up-to-date | INN4 | 2.163 |

| Employer branding | ||

| Is a good institution to work for | EBR1 | 2.306 |

| Cares for the well-being of its staff | EBR2 | 2.934 |

| Attracts a high standard of employees | EBR5 | 2.598 |

| Integrity | ||

| Is open and transparent about its procedures and client relationships | INT1 | 2.173 |

| Its directors use their power responsibly | INT3 | 2.173 |

| Leadership | ||

| Has a strong and well-respected president/CEO | LEA2 | 2.480 |

| Is well organized | LEA3 | 2.480 |

| Reliability and financial strength | ||

| Generates benefits | REL2 | 2.570 |

| Its operations are completely secure | REL6 | 2.369 |

| Its marketing is appealing and sincere | REL7 | 2.318 |

| Is recognized on an international level | REL10 | 2.488 |

| Social action | ||

| Has environmentally sound targets | SA1 | 2.114 |

| Is committed socially: giving grants and founding educational, cultural, and offering assistance to catastrophes, poverty and developmental co-operation. | SA2 | 2.283 |

| Its role in society clearly exceeds the simple desire of profits. | SA3 | 2.459 |

The nomological validity of the model is tested by linking corporate reputation to two of the most common consequences: loyalty and word of mouth (Walsh and Beatty, 2007; Walsh et al., 2009b). Given that satisfaction and trust have also been considered as antecedents of loyalty and word of mouth (Walsh et al., 2009b; Ladhari et al., 2011), these relationships are also studied in the analysis, reinforcing the nomological test of the model, which is completed by adding the analysis of loyalty as an antecedent of word of mouth (see Fig. 1 in “Hypotheses testing” section).

Bank reputation is confirmed as an antecedent of loyalty (β=0.185; p<0.01) but satisfaction has the greatest effect on loyalty (β=0.496; p<0.01), followed by trust (β=0.274; p<0.01) and reputation. Word of mouth is a quasi-significant outcome of reputation (β=0.052; p<0.10). Satisfaction (β=0.311; p<0.01) is the main predictor of word of mouth, followed by trust (β=0.104; p<0.05) and reputation with lower influence. Loyalty is also confirmed as the main predictor of word of mouth (β=0.522; p<0.01). These relationships with reputation outcomes guarantee the nomological validity.

Once the quality of the measurement instrument has been checked, the structural model is assessed, on the basis of the analysis of the coefficient of determination (R2) and the Stone-Geisser criterion (Q2) (Geisser, 1974; Stone, 1974; Chin, 1995) (Table 8). The R2 for endogenous constructs amply exceed the threshold of 0.1 (Falk and Miller, 1992), even higher than 0.75 (Hair et al., 2011). In PLS, the Q2 test gives more information about the predictive relevance of the model than R2 and AVE. The Q2 for endogenous constructs with a reflective measurement model, obtained through blindfolding, is higher than 0 (Chin, 1998a,b). These results guarantee the predictive relevance of the structural model.

Hypotheses testingOnly four out of the ten hypotheses related to antecedents of reputation are confirmed (Fig. 1). The cognitive dimensions of reliability and financial strength (β=0.470, p<0.01) and leadership (β=0.357, p<0.01) are the most important antecedents of reputation of the financial institutions analyzed. Hence, hypotheses H6 and H7 are supported. Offer has a negative and significant effect on reputation (β=−0.254, p<0.01), just as integrity (β=−0.141, p<0.1) and social action (β=−0.091, p<0.1), although the last two ones have quasi-significant coefficients. Thus, hypotheses H1, H5 and H8 are not supported since the sign of the relationship is contrary to what was expected. The constructs of customer care (β=−0.060; p>0.1), innovation (β=0.084; p>0.1) and employer branding (β=0.002; p>0.1) are not confirmed as antecedents of reputation, not supporting H2, H3 and H4. In the case of emotional dimensions, both satisfaction (β=0.315, p<0.01) and trust (β=0.187; p<0.01) are confirmed as antecedents of reputation due to their positive and significant contribution, supporting H9 and H10.

The nomological analysis performed in the previous section enables to verify that hypotheses H11 and H12 are supported. These hypotheses proposed, respectively, customer loyalty (β=0.185; p<0.01) and word of mouth behavior (β=0.052; p<0.10) as consequences of bank reputation, although word of mouth is a quasi-significant outcome of reputation.

Table 9 shows a summary of hypotheses testing.

Hypotheses testing.

| Hypotheses | Relationship | Support? |

| H1 | Offer→Reputation | NO |

| H2 | Customer care→Reputation | NO |

| H3 | Innovation→Reputation | NO |

| H4 | Employer branding→Reputation | NO |

| H5 | Integrity→Reputation | NO |

| H6 | Leadership→Reputation | YES |

| H7 | Reliability→Reputation | YES |

| H8 | Social Action→Reputation | NO |

| H9 | Satisfaction→Reputation | YES |

| H10 | Trust→Reputation | YES |

| H11 | Reputation→Loyalty | YES |

| H12 | Reputation→Word of mouth | YES |

Considering that the especially unfavorable conditions of one of the banks analyzed (Bankia) in the moment of the study could affect the results of the research, the analysis of the structural model is based on two different samples: the analysis including the total sample (global model) and the analysis that excludes Bankia customers (model without Bankia). In this last model, the hypotheses testing offers results similar to the global model. The dimensions of reliability and financial strength (β=0.294; p<0.05) and leadership (β=0.357; p<0.01) are confirmed as the only cognitive dimensions that have a direct effect on reputation, although the relative importance of leadership is higher in this case. The inverse relationship between reputation and integrity (β=−0.365; p<0.01) and social action (β=−0.147; p<0.05) is also reproduced in the model without Bankia, although the level of effect and significance is higher than in the global model. However, contrary to this last one, the negative relationship between offer and reputation is not significant (β=−0.147; p>0.1). The effect that non-significant dimensions had on the global model is not either significant in the model without Bankia: customer care (β=0.038; p>0.1), innovation (β=0.147; p>0.1) and employer branding (β=−0.117; p>0.1). Emotional dimensions, satisfaction (β=0.410; p<0.01) and trust (β=0.261; p<0.01), are also confirmed as significant antecedents of reputation.

As a conclusion of this comparative analysis of the two models, it can be said that the antecedents of reputation are the same in both cases although there are differences in the relative importance of each one of them. Hence, it may be concluded that the assessments of Bankia customers would not be conditioning in a relevant way the results achieved in the global model, what makes it possible to verify the robustness of the reputation model developed in this study.

Conclusions and managerial implicationsEmpirical and theoretical conclusionsThis study contributes to academic research by presenting a formative index of reputation that integrates the most relevant dimensions of the existing literature, analyzing bank reputation among customers, both from the perspective of cognitive and emotional components.

The results obtained in this study significantly contrast with previous works (Flavián et al., 2004, 2005; Walsh and Beatty, 2007; García de los Salmones et al., 2009; Bravo et al., 2009b; Chen and Chen, 2009; Walsh et al., 2009a; Bravo et al., 2010a; Akdag and Zineldin, 2011) that analyze the perceptions that bank customers have in different contextual circumstances. This involves an empirical evidence that reputation measurement models must be adapted very accurately to the conditions of the environment at the time of the analysis, so that they become a really effective tool in business practice. In this regard, reputation would be specific both to the particular sector where the company interacts and to the target group (Ruiz et al., 2012b), along with the current socioeconomic context. The variation of the conditions of the environment modifies the stakeholders’ mindsets, in such a way that key aspects in the past for them can be less interesting or relevant in a different context.

Among the different conclusions, it is observed that an unfavorable reputation of the financial institutions would be negatively related to customer loyalty and their unwillingness to make comments or positive recommendations of it. Hence, it is confirmed how important it is for banks to know the determinants of their reputation in order to get to design effective strategic policies of marketing and organization. The empirical results of this work show that, in a condition of economic crisis where financial institutions are thought to have the primary responsibility for the current situation, the dimensions that positively condition their reputation are the reliability and financial strength that the institution conveys, and the leadership role of their managers; as well as the satisfaction and trust that customers feel as customers of the institution.

Issues such as the appeal of the offer, managers’ integrity and social action, show an inverse relationship with bank reputation. These results must be interpreted taking into account that global indicators have been used in the methodology of this study to measure global reputation. The advantage that this method presents is that it enables to draw assessments of reputation independent of the ones made in each one of the dimensions. Thus, far from interpreting that customer reject these issues, in the cases of offer and social action, these results can be obtained due to the fact that the main institutions are not known neither for having the most appealing offer nor for being the most involved in social issues. In this way, customers assume that the most reputable entities are not being differentiated for having the largest variety of products, the best services, or the best market terms. The most reputable financial institutions would be focusing their efforts on offering a range of products more austere but less risky, according to the economic context prevailing at the time of the empirical research. They are not differentiated either for being the most committed to environmental protection or to social causes, or for having an altruistic vision.

Other papers can be found in literature where bank overpricing becomes an indicator of quality, since it assures that the future value of income exceeds the possible benefits of fraud (Klein and Leffler, 1981; Shapiro, 1983). Fang (2005) proposes that under equilibrium the most reputable banks should offer lower-risk products, set higher prices and receive higher remuneration. This theory would apply in a market situation such as the current situation at the time of the fieldwork, where the security of bank products and services is publicly doubted. In this research, price (the attraction power of interest rates) is one of the explanatory variables of offer, but not the most influential one. However, the criterion of Fang (2005) may explain the inverse direction of the relationship between the dimension of offer at a global level and reputation.

In the literature the relationship between social action and reputation has been found to be direct, neutral or inverse (Brown and Dacin, 1997; Sen and Bhattacharya, 2001), since according to Devinney et al. (2006), people are not as noble as surveys show and their commitment to society finishes when it touches their own interests. The inverse relationship conveyed in this study is not expected to be caused by a lack of credibility (Matute et al., 2010) of banking social action, since there is not any reference at an academic or professional level suggesting that consumers are suspicious of their altruist nature. In fact, this result would be conditioned because customers consider that most reputable institutions are not making every possible social effort. In other words, customers give more value to institutions that stand out by their ability to take care of customers’ economic interests, with a well-known board of directors, despite their social actions are pnot reaching the same level of acknowledgment.

There is no earlier reference in the literature to an inverse relationship between integrity and reputation, but the economic crisis has been related from the beginning to the lack of integrity of corporate governances (Bouchikhi and Kimberley, 2008). Therefore, the inverse relationship might accordingly be justified by the special circumstances surrounding the banking industry at the time of the fieldwork, where the transparency and responsibility of the banking system in general are being called into question in all fields: professional and not professional. Respondents may have been isolating their reputation views from their perceptions of integrity since this would be discarded a priori for every organization in the financial system. Then, coinciding with the results of the study of Burke et al. (2011), the rest of the financial industry would be also affected by the behavior of the financial institutions that have assumed more risks.

Additionally, the dimension of customer care, with particular relevance in previous works (Walsh and Beatty, 2007; Flavián et al., 2005; García de los Salmones et al., 2009), is not confirmed in this study as antecedent of bank reputation, coinciding with the conclusions of Nguyen and LeBlanc (2001). This result could be due to the fact that customers do not seem to perceive differences in the customer care offered by the various financial institutions, as it is confirmed in the study of Bravo et al. (2009a). This reasoning would also justify the conclusions extracted by Bravo et al. (2010a), revealing how customer care does not have an effect on the value given to the service provided by financial institutions. One possible explanation is provided by García de los Salmones and Rodríguez del Bosque (2006), who have observed that issues related to customer care are only significant in the case of companies that are not firmly established in the market, which is not the case of the firms under consideration here.

Innovation and employer branding are not confirmed as bank reputation dimensions either. Coinciding with the study of Bravo et al. (2010b), the aspects related to bank services innovation do not seem to have an impact on the bank customers’ perceptions. The quick reaction of banks to the innovations that their competitors come up with makes customers not to perceive substantial differences among them. Employer branding could also be perceived in a similar way among banks; or maybe in this new socio-economic context, where public concerns seem to have changed, this issue could have been relegated in the assessments of bank customers.

In short, bank reputation would be mainly conditioned by those factors that show the ability of the financial institution to manage more effectively the interests of the customers, with a board of directors recognized for their successful professional careers who, at the same time, manage to maintain high levels of satisfaction and trust among their customers.

Managerial implicationsMost works that have analyzed the perceptions that customers have about their banks, have been carried out in situations of economic and social stability, existing little empirical evidence on what the true values of customers in a situation of economic crisis are, where the modus operandi of banks in the past has generated anger and distrust among the general population. The results of this study, started the same day that the Minister of Economy announced the rescue request of the Spanish banking system to Europe, offer banks information about the values that they should promote at a time when, for the first time, they are in the spotlight of population in general.

In this study, it is observed that favorable reputation of banks is positively related to customer loyalty and their willingness to highly recommend it. Given the impact that in this sense the favorable behavior of consumers has on the organizations’ benefits (Heskett et al., 1990; Molina et al., 2007), it is important for banks to get to know how their reputations are configured in each moment, in order to integrate this knowledge in the design of their business strategies and, thus, to improve their competitiveness by guaranteeing their long-term survival and success.

According to the results of this work, in situations of economic crisis as the one happened suddenly at the end of the first decade of the XXI century, the key values where to focus the management programs of the reputation of the leading banks are those that make them be perceived among their consumers as reliable and financially strong institutions, with leading and influencing boards of directors, without neglecting customer satisfaction and trust.

Reliability and financial strength of the financial institution is the dimension that conditions the most the perceptions that bank customers have. In this regard, it is better for banks to practice transparency and sincerity, to take care of their profitability and financial strength, to internationally reinforce their prestige and recognition, guaranteeing at any time their operational arrangements. The way in which customers see the leadership existing within banks is one of the most important values of bank reputation. In order to promote this issue, banks should develop strategic actions that boost the role of their leaders as a key “player” in the organization, showing that their leaders have a clear idea of the future of the institution and that they guarantee a good internal organization of the company.

Actions oriented to the search of consumer satisfaction and trust are also key factors in the bank reputation strategy. Hence, banks must not only develop programs aimed at promoting cognitive dimensions (reliability/financial strength and leadership), where firms can act directly, but they must also work on their customers’ emotions trying to achieve their maximum levels of satisfaction and trust.

Although the negative association of offer, integrity and social action with reputation seems to confirm that bank customers assume that the most reputable banks are not characterized by dealing with these issues, marketing programs aimed at restoring the perception that customers have of these concepts would be an advisable action in bank reputation management. Managers have a natural inclination to overestimate their organization and their own skills, and to believe that their company has a good reputation in certain areas if there is no indication of the contrary (Eccles et al., 2007). However, financial institutions managers that enjoy favorable reputations should also consider the reality of their organizations and revise issues related to offer, integrity and social action, orienting their reputation programs to improve the perceptions that customers have of these aspects and getting, in this way, to stand out among their most direct competitors.

It is not concluded in this study that the dimensions of customer care, innovation and employer branding have a significant effect on bank reputation. In this respect, when designing their reputation management programs, banks should reconsider the priority of these concepts that in other contexts seem to have a more relevant role. Nevertheless, banks should not neglect these issues either, since a negative perception of the customers regarding some of them could break the limited differentiation existing in the market in relation to these aspects, negatively highlighting the institution among its competitors and damaging its reputation.

Limitations and main research linesThe first limitation of this study deals with the method used to measure satisfaction and trust. These dimensions show themselves as two key aspects of bank reputation; however, their measurement is carried out through a reflective approach, with global indicators, that prevents from knowing what the particular aspects that the companies should deal with in order to improve these issues are. The second limitation is derived from avoiding the analysis of differences between bank customers and savings bank customers, who could be assessing reputation criteria of banks with different foundational origins in a different way. Thirdly, banks of different size and positioning are not taken into account, preventing from contrasting if non-significant dimensions in this study are so in the case of banks with other characteristics, and vice versa. Another limitation lies in the use of an online questionnaire that could be excluding the public who is not familiar with the use of Internet.

The proposal of future research lines is mainly oriented to solve the limitations that have just been explained above. In this respect, the analysis of the determinants of satisfaction and trust of bank customers is proposed, checking as well how rational dimensions of reputation condition these two emotional ones. Secondly, a multigroup analysis is suggested in order to study the differences between bank customers and savings bank customers. The third proposal suggests repeating the study among the main customers of banks of different size and positioning, developing a multigroup analysis that identifies the existence of significant differences among the customers of this type of banks. And, last but not least, the repetition of this study is proposed after a noticeable change in the surrounding conditions in order to achieve a longitudinal view of the relative importance of the antecedents of corporate reputation.

| Variable | Features | Total | BBVA | Santander | BANKIA | La Caixa |

| % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Gender | Men | 45.9% | 54.0% | 50.5% | 35.6% | 43.6% |

| Women | 54.1% | 46.0% | 49.5% | 64.4% | 56.4% | |

| Age | 18–29 | 19.7% | 13.0% | 21.2% | 28.7% | 15.8% |

| 30–39 | 29.9% | 28.0% | 33.3% | 25.7% | 32.7% | |

| 40–49 | 25.2% | 29.0% | 23.2% | 25.7% | 22.8% | |

| 50–59 | 18.2% | 22.0% | 16.2% | 16.8% | 17.8% | |

| ≥60 | 7.0% | 8.0% | 6.1% | 3.0% | 10.9% | |

| Marital status | Single | 24.2% | 22.0% | 22.2% | 32.7% | 19.8% |

| Living as a couple | 19.5% | 19.0% | 21.2% | 15.8% | 21.8% | |

| Married | 50.1% | 52.0% | 52.5% | 43.6% | 52.5% | |

| Separated/divorced | 5.5% | 5.0% | 4.0% | 6.9% | 5.9% | |

| Widower | 0.7% | 2.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | |

| Education | Primary | 2.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 4.0% | 3.0% |

| Secondary | 11.5% | 13.0% | 10.1% | 13.9% | 8.9% | |

| Professional study | 22.4% | 30.0% | 16.2% | 22.8% | 20.8% | |

| University | 64.1% | 57.0% | 72.7% | 59.4% | 67.3% | |

| Occupation | Employed | 79.8% | 81.0% | 75.8% | 81.2% | 81.2% |

| Self-employed | 11.6% | 11.0% | 16.2% | 9.9% | 8.8% | |

| Unemployed | 4.7% | 4.0% | 2.0% | 7.9% | 5.0% | |

| Student | 2.0% | 1.0% | 4.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | |

| Retired | 1.7% | 3.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | |

| Other occupation | 0.2% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Monthly salary | <1.000 € | 7.0% | 4.0% | 5.5% | 3.0% | 8.1% |

| 1.000–2.000 € | 30.0% | 28.7% | 28.7% | 30.7% | 25.3% | |

| 2.001–3.000 € | 23.0% | 25.7% | 25.4% | 28.7% | 24.2% | |

| Over 3.000 € | 11.0% | 15.8% | 15.7% | 16.8% | 19.2% | |

| Prefer not to answer | 29.0% | 25.7% | 24.7% | 20.8% | 23.2% |

| Offer |

| Bloemer et al. (1998); Athanassopoulos et al. (2001); Caruana (2002); Wang et al. (2003); Flavián et al. (2005); García de los Salmones and Rodríguez del Bosque (2006); Lewis and Soureli (2006); Molina et al. (2007); Hansen and Sand (2008); Bravo et al. (2009b); García de los Salmones et al. (2009); Kumar et al. (2009); Matute et al. (2010); Pisnik and Snoj (2010); Akdag and Zineldin (2011); Ladhari et al. (2011); Rep Trak Pulse (2012) |

| OFF1- Its products and services meet my needs |

| OFF2- Its services and decision making are quick |

| OFF3- Offers a wide and complete range of products |

| OFF4- Keeps its customers well informed of their accounts and of new products |

| OFF5- Offers the most attractive conditions for savings and debt products |

| OFF6- Its service costs (commissions) are reasonable |

| OFF7- Adapts the conditions of its products to the economic status of its clients |

| OFF8- Solves problems quickly |

| OFF9- Its range of offered products and services are appealing |

| Customer care |

| Levesque and McDougall (1996); Bloemer et al. (1998); Athanassopoulos et al. (2001); Caruana (2002); Wang et al. (2003); Flavián et al. (2005); García de los Salmones and Rodríguez del Bosque (2006); Lewis and Soureli (2006); Molina et al. (2007); Walsh and Beatty (2007); Hansen and Sand (2008); Boshoff (2009); Bravo et al. (2009b); García de los Salmones et al. (2009); Kumar et al. (2009); Walsh et al. (2009a,b); Bravo et al. (2010a); Nguyen (2010); Pisnik and Snoj (2010); Akdag and Zineldin (2011); Bartikowski and Walsh (2011); Ganguli and Roy (2011); Merco Financial Brands (2010) |

| CTC1- Its employees care about my needs |

| CTC2- Its employees treat me with consideration |

| CTC3- Has personnel who anticipates my needs |

| CTC4- Its employees are willing to assist me when needed |

| CTC5- Its employees are expert in financial matters |

| CTC6- Its personal is expert |

| CTC7- Its staff recognize me |

| CTC8- The advice received form my personal account officer matches my needs |

| CTC9- The advice received form my personal account officer gives a clear and detailed view (the pros and cons) regarding product and services |

| CTC10- I trust the staff of my institution |

| CTC11- Its telephone banking service is good |

| CTC12- Its online service is good |

| Innovation |

| Fombrun et al. (2000); Caruana (2002); Wang et al. (2003); García de los Salmones and Rodríguez del Bosque (2006); Lewis and Soureli (2006); Martín-Consuegra et al. (2008); Bravo et al. (2009b); Walsh et al. (2009a); Pisnik and Snoj (2010); Akdag and Zineldin (2011); Ladhari et al. (2011); Rep Trak Pulse (2012) |

| INN1- Easily adapts to economic changes, new customer trends and general market developments |

| INN2- Tends to innovate rather than imitate |

| INN3- Tends to be the first to introduce new products and services |

| INN4- Its equipment and technology are up to date |

| Employer branding |

| Fombrun et al. (2000); Schwaiger (2004); Walsh and Beatty (2007); Walsh et al. (2009a,b); Bartikowski and Walsh (2011); Rep Trak Pulse (2012) |

| EBR1- Is a good institution to work for |

| EBR2- Cares for the well-being of its staff |

| EBR3- Offers a its staff a fair wage |

| EBR4- Offers equal opportunities to all the staff |

| EBR5- Attracts a high standard of employees |

| EBR6- Offers reliable employment |

| Integrity |

| Bravo et al. (2009b); Rep Trak Pulse (2012) |

| INT1- Is open and transparent about its procedures and client relationships |

| INT2- Behaves ethically and honesty |

| INT3- Its directors use their power responsibly |

| Leadership |

| Fombrun et al. (2000); Schwaiger (2004); García de los Salmones and Rodríguez del Bosque (2006); Walsh and Beatty (2007); Boshoff (2009); Rep Trak Pulse (2012) |

| LEA1- Its direction has a clear view of the future |

| LEA2- Has a strong and well-respected president/CEO |

| LEA3- Is well organized |

| Reliability and financial strength |

| Bloemer et al. (1998); Fombrun et al. (2000); Caruana (2002); Wang et al. (2003); Schwaiger (2004); Helm (2005); García de los Salmones and Rodríguez del Bosque (2006); Walsh and Beatty (2007); Boshoff (2009); Bravo et al. (2009b); García de los Salmones et al. (2009); Kumar et al. (2009); Walsh et al. (2009a,b); Bartikowski and Walsh (2011); Merco Financial Brands (2010); Rep Trak Pulse (2012) |

| REL1- Clearly supersedes its competitors |

| REL2- Generates benefits |

| REL3- Has potential to grow in the future |

| REL4- Has a lower risk than its competitors |

| REL5- Is solvent and financially strong |

| REL6- Its operations are completely secure |

| REL7- Its communication messages are appealing and sincere |

| REL8- The information that I receive about this institution through the media inspire confidence |

| REL9- The information that I receive about this institution through my acquaintances/friends inspires confidence |

| REL10- Is recognized on an international level |

| REL11- Is strong enough to prevail over the current crisis |

| Social action |

| Bloemer et al. (1998); Fombrun et al. (2000); Sen and Bhattacharya (2001); Schwaiger (2004); García de los Salmones and Rodríguez del Bosque (2006); Boshoff (2009); Bravo et al. (2009b); García de los Salmones et al. (2009); Walsh et al. (2009a,b); Bravo et al. (2010a); Matute et al. (2010); Nguyen (2010); Bartikowski and Walsh (2011); Pérez (2011); Merco Financial Brands (2010); Rep Trak Pulse (2012) |

| SA1- Has environmentally sound targets |

| SA2- Is committed socially: giving grants and founding educational, cultural, and offering assistance to catastrophes, poverty and developmental co-operation |

| SA3- Its role in society clearly exceeds the simple desire of profits |

| Satisfaction |

| Levesque and McDougall (1996); Jamal and Naser (2002); Caruana (2002); Walsh and Beatty (2007); García de los Salmones et al. (2009); Walsh et al. (2009b); Bravo et al. (2010a); Matute et al. (2010); Pisnik and Snoj (2010); Ladhari et al. (2011); Pérez (2011) |

| SAT1- In general terms I feel satisfied with my financial institution |

| SAT2- This institution fulfills my expectations |

| SAT3- I am glad that I chose this institution |

| Trust |

| Flavián et al. (2005); Lewis and Soureli (2006) |

| TRU1- I feel that I can trust this institution |

| TRU2- I feel that my accounts are safe with this institution |

| TRU3- Management of this institution has my best interests at heart |

| Overall reputation |

| Nguyen and LeBlanc (2001); Walsh and Beatty (2007) |

| REP1- From my point of view, this institution has a good reputation |

| REP2- The general public's opinion is that this institution has a good reputation |

| REP3- I believe that the reputation of this institution is better than other institutions |

| Loyalty |

| Caruana (2002); Lewis and Soureli (2006); Walsh and Beatty (2007); Walsh et al. (2009b); Bartikowski and Walsh (2011) |

| LOY1- This institution is clearly the best to do business with |

| LOY2- Really like to do business with this institution |

| LOY3- I tend to remain the institution's customer |

| Word of mouth |

| Walsh and Beatty (2007); Walsh et al. (2009b) |

| WOM1- If I were asked, I would recommend becoming a customer of this institution |

| WOM2- I am likely to say good things about this institution |

| WOM3- I would recommend this institution to my friends and acquaintances |

This standard may be competence, the average reputation for the sector or the reputation levels of the company in the past, among others.

Spain goes into recession in the fourth quarter of 2008 when GDP fell by 1.1% quarter on quarter (INE.es, May 17th, 2012).

Capital requirements imposed by the bank restructuring started in 2011 imply that savings banks are turned into banks. Consequently, at the time of the study, Bankia and La Caixa are constituted as public limited companies with bank statutes, although during the presentation of the new societies the presidents of both institutions stated their status as savings banks.